Abstract

Toxoplasma retinochoroiditis in pregnancy may create considerable patient anxiety and is a dilemma for the treating ophthalmologist. A case report highlighting this clinical issue is presented followed by a review of the literature. Consensus in relation to the management of toxoplasma retinochoroiditis in pregnancy is lacking and is discussed.

Keywords: toxoplasma, retinochoroiditis, pregnancy

Case report

A 31-year-old immunocompetent female in the 9th week of her first pregnancy attended the emergency eye clinic with a one-week history of painless blurred vision in the right eye.

Previous ocular history included right toxoplasma retinochoroiditis when aged 11 years, and an episode of undiagnosed blurred vision in the same eye three years previously. She was otherwise in good general health.

On examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 6/18 RE and 6/6 LE. There was no ciliary injection in the right eye. 3+ cells with keratitic precipitates were present in the right anterior chamber. Posterior synechiae were absent. 1+ vitreous cells with vitreous veils were present. Fundoscopy showed a raised pale ‘satellite lesion’ at the right macula with three adjacent chorioretinal scars. The optic disc was mildly swollen (Figure 1). An inactive scar was also evident in the temporal fundus of the left eye (Figure 2).

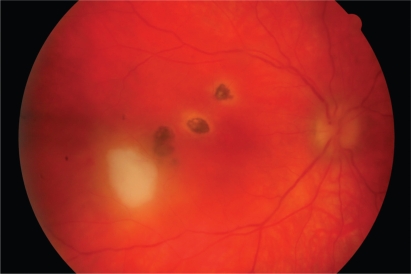

Figure 1.

Recurrent toxoplasma retinochoroiditis. A ‘satellite lesion’ associated with pre-existing retinochoroidal scars is present at the right macula. The lesion became inactive over a period of several weeks. The acute retinochoroiditis extended temporally from the fovea.

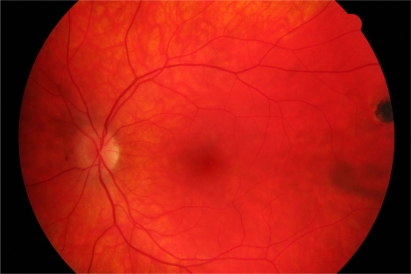

Figure 2.

Inactive chorioretinal scar in temporal periphery of left eye.

We diagnosed recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis with macular involvement. Investigations at presentation included negative toxoplasma immunoglobulin M (IgM).

The patient was treated with intensive topical steroid and a mydriatic only, avoiding the use of systemic antimicrobial and steroid medications. The obstetric team maintained close surveillance on the pregnancy. Over the next few months, there was gradual clinical improvement and the topical steroids were slowly tapered. At 22 weeks of gestation, visual acuity had improved to 6/9 RE. The intraocular inflammation had settled and the retinal lesion appeared flatter with the edges starting to pigment. Five months after first presentation, the retinal lesion had become quiescent and visual acuity was 6/6.

Discussion

Toxoplasmosis is caused by the obligate intracellular protozoan Toxoplasma gondii.

Recurrent ocular disease is a common cause of posterior uveitis and may be sight-threatening, particularly if lesions involve the macula or severe intraocular inflammation is present. Immunocompetent patients usually have only one focus of active retinal disease. The retinitis usually resolves by two months, although associated intraocular inflammation may take longer.1 The process underlying reactivation of the parasite in the retina is not known.

Pregnancy may create a change in the hormonal or immunological environment of the mother that favours reactivation of ocular toxoplasmosis.2,3 Bosch-Driesden and colleagues reported that seven (9%) of 82 women with ocular toxoplasmosis developed recurrences during pregnancy.4 Reports are conflicting as to whether or not pregnancy is associated with more aggressive recurrences.3,5

It is accepted that primary infection in healthy women or reactivated infection in immunocompromised women can result in transplacental transmission if not treated, resulting in congenital toxoplasmosis.6 Systemic treatment has been shown to decrease the rate of transmission as well as the incidence of congenital toxoplasmosis.7 Management of such clinical scenarios is therefore more defined, and the use of toxic treatments more justifiable. Furthermore, most ophthalmologists would consider systemic treatment (including aggressive efforts with multiple therapy) in immunocompetent patients with ocular toxoplasmosis presenting with lesions involving the macula or in close proximity to the optic disc.

However, reactivation of toxoplasma retinochoroiditis threatening vision during the first trimester of pregnancy in a healthy female presents a difficult management problem. This view is supported by the results of a US survey of 457 ophthalmologists in which almost 25% of retinal subspecialists and 40% of general ophthalmologists were “not sure” how they would manage a pregnant patient with recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis and normal immune function.8

We reviewed the published evidence so that we could determine an optimal management strategy and, at the same time, provide the patient with information to address her concerns about any increased risk to both her own health and that of her unborn child from treatment or nontreatment. We found the published studies fell broadly into three main categories: (1) clinical and laboratory diagnosis to support or preclude intervention, (2) the risk of fetal infection associated with reactivated ocular toxoplasmosis in the mother, and (3) the risk of not treating the mother vs potential teratogenicity associated with some antitoxoplasma agents. The literature review was based on comprehensive Medline and Embase searches generating references on ocular toxoplasmosis published predominantly in the last 20 years.

Investigations

Diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis is primarily based on clinical findings. However, a wide spectrum of clinical features may be present making the distinction with other causes of retinochoroiditis problematic.9 In some cases, difficulty may exist in differentiating primary and reactivated ocular disease, thereby making the evaluation of the risk of transplacental transmission and the need for therapy difficult to assess.10

It is well accepted that the role of serological investigation in the management of ocular toxoplasmosis is limited.11 However, serological tests may be used as supportive evidence to confirm the suspected clinical diagnosis, particularly in complex cases. Such investigations may also be warranted in pregnant patients in whom there is a conflict between the potential benefits of treatment and the risk of treatment toxicity to the fetus.

Serological changes in acute systemic infection include the presence of anti-T. gondii IgM in serum and a rising or significantly raised level of anti-T. gondii IgG.12 Anti-T. gondii IgM levels may be detectable for at least 18 months following acute infection.11 Detection of anti-T. gondii IgA in serum has also been reported to be helpful in the diagnosis of recently acquired infections.12 The high prevalence of anti-T. gondii IgG in an asymptomatic, ‘normal’ population makes the value of its detection somewhat limited.13

In patients with retinochoroidal reactivation, there are often no serological changes to aid the clinician, and the diagnosis is weighted on clinical examination. Peripheral parasitemia is typically negative, suggesting reactivation is localized to the eye. Invasive procedures have been used to determine intraocular antibody production or to detect T. gondii DNA by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of aqueous or vitreous humor samples.14 However, obtaining ocular tissue solely for the purpose of diagnosis is not yet common or established practice in the UK.15

IgG dominates the intraocular antibody response against the parasite.16 Intraocular production of anti-T. gondii IgG has been more frequently noted in patients with recurrent than primary ocular toxoplasmosis (isolated retinal lesions not arising from scars). The presence of intraocular anti-T. gondii IgA antibodies during recurrent disease may provide an important additional tool.12,16 The detection of T. gondii DNA in aqueous or vitreous humor is more frequently found in patients with primary ocular toxoplasmosis than in those with recurrent disease.12,14

Risk of fetal transmission

Ocular disease is mainly associated with the chronic phase of infection with T. gondii, but may also occur during the acute phase of systemic infection (lasting several months) when anti-T. gondii IgM is still detectable. During primary maternal toxoplasmosis, fetal infection occurs as a result of maternal parasitemia and subsequent involvement of the placenta. The first trimester is associated with the lowest rate of fetal transmission, but carries the greatest risk of severe congenital disease (ie, there is an inverse relationship).

It is generally accepted that there is no significant risk of transmission to the fetus where infection in the immunocompetent mother was acquired before conception, even if ocular disease reactivates during pregnancy. This is likely because reactivation is often localised within the eye, and any viable organism entering the blood would be attenuated rapidly due to the action of serum complement activated by circulating antitoxoplasma IgG.

However, the possibility of risk of transmission from mother to child associated with infection acquired months or years prior to conception cannot be excluded unequivocally, albeit that this is likely to be a very rare occurrence.17,18 This view is based on a small number of case reports suggesting women with inactive retinal scars due to toxoplasmosis, or who were known to have long-standing antitoxoplasma IgG antibodies, are also at risk of transmitting this disease to the fetus.17,19 This finding could be accounted for by a down-regulation of the T-cell-mediated immune response that is observed during pregnancy.20 Another explanation put forward is that re-infection or new infection with a different strain of the parasite may occur.21 This has not been demonstrated conclusively by laboratory studies as current serologic tests are not subtype-specific, but suggested indirectly by the presence of rising titers of maternal IgG and/or IgM.17 It has also been suggested that maternal infection just preceding conception may lead to transmission, as the parasitemia may remain active even months after initial exposure.17

Treatment considerations

The traditional approach for the treatment of sight-threatening ocular toxoplasmosis is to use multiple anti-parasitic drugs systemically with or without corticosteroids to reduce retinal scarring and limit damage caused by intraocular inflammation.22 Vision, lesion location, lesion size, and vitreous inflammatory reaction have been identified as indications for systemic treatment.23

There is no consensus regarding the best treatment regimen in nonimmunocompromised, nonpregnant patients.23,24 (Table 1) Furthermore, it has been suggested that treatment may not alter the natural history of the disease, and may even do more harm than good.1

Table 1.

| Regimenc | Respondents in 2001 survey |

|---|---|

| Pyrimethamine/folinic acid,d sulfadiazine, prednisonee | 23/78 (29%) |

| Pyrimethamine/folinic acid,d sulfadiazine, clindamycin, prednisonef | 10/78 (13%) |

| Sulfadiazine, clindamycin, prednisone | 1/78 (1%) |

| Clindamycin, prednisone | 8/78 (10%) |

| Pyrimethamine/folinic acid, TMP/SMX, prednisone | 5/78 (6%) |

| Pyrimethamine,g TMP/SMX, clindamycin, prednisone | 4/78 (5%) |

| Pyrimethamine/folinic acid,d sulfadiazine | 3/78 (4%) |

| TMP/SMX, clindamycin, prednisone | 3/78 (4%) |

| TMP/SMX, clindamycin | 3/78 (4%) |

| TMP/SMX, prednisone | 3/78 (4%) |

| Spiramycin, prednisone | 2/78 (3%) |

Notes:

Copyright © 2002. Modified with permission from Holland GN, Lewis KG. An update on current practices in the management of ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:102–114. A written questionnaire was distributed to all physician members (n = 147) of the American Uveitis Society in 2001 about treatment practices for ocular toxoplasmosis.

A typical case was defined as an immunocompetent male or nonpregnant female patient with a lesion threatening the macula or optic nerve head, who has decreased vision but potential for full recovery of central vision.

All drug combinations cited by more than one respondent in 2001 survey.

Use of folinic acid was mentioned by some, but not all, respondents for these regimens in the 2001 survey.

Referred to by some clinicians as ‘classic therapy.’

Referred to by some clinicians as ‘quadruple therapy.’

The use of folinic acid was not specifically mentioned by respondents for this regimen.

Abbreviation: TMP/SMX, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.

Unsurprisingly, therefore, the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis during pregnancy creates an even greater challenge, as the therapeutic options are particularly limited3. In principle, drugs should only be prescribed in pregnancy if the expected benefit to the mother is thought to be greater than the risk to the fetus. Few if any medications are safe beyond all doubt, particularly in the first trimester when the risk of congenital malformation is greatest.

Ophthalmologists may be less willing to treat pregnant patients with recurrent disease due to concerns over treatment toxicity.8 Consideration may be given to shortening the course of therapy, particularly in patients whose disease responds rapidly to treatment, or consider monotherapy.23 The choice of therapy will depend on whether the maternal ocular infection is acquired or reactivated during pregnancy, and whether there is any evidence of congenital infection.

Ophthalmologists should consult with the patient’s obstetrician and an infectious disease specialist before considering systemic treatment in pregnancy for ocular toxoplasmosis. Patients should also be informed of their options including the benefits and theoretical risks of anti-toxoplasma medical therapy during the first trimester of pregnancy.

‘Classic therapy’ for ocular toxoplasmosis comprises a combination of pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and prednisolone. However, pyrimethamine should be avoided in pregnancy due to concerns about its potential for teratogenicity, especially in the first trimester.3 Sulphonamides should be avoided in the third trimester, because they compete with bilirubin for serum proteins, causing kernicterus.3 However, in continental Europe, both pyrimethamine and sulphonamides are used to treat ocular toxoplasmosis during pregnancy.20

Consideration should be given to the use of other antimicrobials. Clindamycin, azithromycin and atovaquone have been routinely used for the treatment of nonophthalmic infectious diseases in pregnancy, and shown to be safe and effective.25–27 Clindamycin, which concentrates in ocular tissue and penetrates tissue cyst walls,28 and azithromycin29 may be effective alternative treatments for patients with ocular disease. It has been suggested that a combination of clindamycin and atovaquone, or a combination of clindamycin and azithromycin may be a safe alternative to the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis in pregnant patients.3

Spiramycin, which is only available on a named patient basis in the UK, is also considered a safe agent and is known to concentrate in the placenta, reducing the risk of transplacental infection in newly acquired infections.30 However, spiramycin is not effective for ocular disease.24

Pars plana vitrectomy may have a role in selected patients in removing antigenic proteins and inflammatory debris. Furthermore, intraocular antibiotics may be a useful alternative for pregnant patients with ocular toxoplasmosis, by reducing the risk of systemic toxicity.31 Martinez and colleagues reported a case of a pregnant woman in the first trimester with sight-threatening reactivated ocular toxoplasmosis successfully managed with a combination of intravitreal clindamycin and dexamethasone and systemic sulfadiazine.31

Summary

In conclusion, there is evidence to suggest that pregnancy is linked to the reactivation of ocular toxoplasmosis and pregnant women at risk should, therefore, be informed about this risk.20

Pregnant women can be reassured that vertical transmission secondary to recurrent ocular disease is likely to be a rare event. It has been suggested that pregnant women at risk are monitored every three months by screening fundoscopy, and their offspring then followed systemically to exclude the presence of congenital infection. The detection of vertical transmission to the fetus is not straightforward, however.20 Regular ultrasound examination may be appropriate to look for evidence of fetal involvement.32

Serum antibody titers are of limited value in the confirmation of suspected recurrent ocular disease, and the diagnosis remains heavily weighted on clinical examination. There may be a role for intraocular fluid sampling in complex cases although this is rarely performed in the UK.

Guidelines are lacking regarding the most appropriate anti-parasitic regimens for the treatment of ocular toxoplasmosis, highlighting the need for larger cohort studies. It is not surprising, therefore, that the dilemma in choosing an appropriate treatment strategy for pregnant patients is compounded. New, effective ways are required to treat ocular toxoplasmosis while minimizing fetal toxicity to multiple drugs. In this regard, a combination of intravitreal and systemic therapy may be useful in treating patients with recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis in pregnancy with sight-threatening lesions.31

In the case presented here, we chose, following consultation with the patient, not to use standard treatment despite the presence of a macular lesion. A good visual outcome was achieved. We hope that this article serves to highlight to ophthalmologists alternative management options when dealing with a more challenging case.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Stanford MR, See SE, Jones LV, Gilbert RE. Antibiotics for Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. An evidence-based systematic review. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;110(5):926–931. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: A global reassessment. Part I: Epidemiology and Course of disease. LX Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;136(6):973–988. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2003.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kump LI, Androudi SN, Foster CS. Ocular toxoplasmosis in pregnancy. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2005;33:455–460. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2005.01061.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch-Driessen LE, Berendschot TT, Ongkosuwito JV, Rothova A. Ocular toxoplasmosis: clinical features and prognosis of 154 patients. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:869–878. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(02)00990-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braakenburg AMD, Rothova A. Clinical features of ocular toxoplasmosis during pregnancy. Retina. 2009;29:627–630. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31819a5ff0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couvreur J, Desmonts G. Congenital and maternal toxoplasmosis: A review of 300 congenital cases. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1962;4:519–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn D, Wallon M, Peyron F, Petersen E, Peckham C, Gilbert R. Mother-to-child transmission of toxoplasmosis: risk estimates for clinical counselling. Lancet. 1999;353:1829–1833. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)08220-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lum F, Jones JL, Holland GN, Liesegang TJ. Survey of ophthalmologists about ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140(4):724–726. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2005.04.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Jong PT. Ocular toxoplasmosis: common and rare symptoms and signs. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:391–397. doi: 10.1007/BF02306487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thulliez P, Daffos F, Forestier F. Diagnosis of toxoplasma infection in the pregnant woman and the unborn child: current problems. Scand J Infect Dis. 1992;84(Suppl):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holliman RE, Stevens PJ, Duffy KT, Johnson JD. Serological investigation of ocular toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:353–355. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.6.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ongkosuwito JV, Bosch-Driessen EH, Kijlstra A, Rothova A. Serologic evaluation of patients with primary and recurrent ocular toxoplasmosis for evidence of recent infection. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;128:407–412. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(99)00266-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothova A, van Knapen F, Baarsma GS, Kruit PJ, Loewer-Sieger DH, Kijlstra A. Serology in ocular toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1986;70:615–622. doi: 10.1136/bjo.70.8.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Boer JH, Verhagen C, Bruinenberg M, et al. Evaluation of serological and PCR analysis of intraocular fluids in the diagnosis of infectious uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:650–658. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70631-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kijlstra A, Luyerdijk L, Baarsma GS, et al. Aqueous humor analysis as a diagnostic tool in toxoplasma uveitis. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:383–386. doi: 10.1007/BF02306485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ronday MJH, Ongkosuwito JV, Rothova A, Kijlstra A. Intraocular anti-toxoplasma gondii IgA antibody production in patients with ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1999;127:294–300. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(98)00337-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dollfus H, Dureau P, Hennequin C, et al. Congenital toxoplasma chorioretinitis transmitted by preconceptionally immune women. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1444–1445. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.12.1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hennequin C. Congenital toxoplasmosis acquired from an immune woman. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:75–76. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199701000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Silveira C, Ferreira R, Muccioli C, Nussenblatt R, Belfort R. Toxoplasmosis transmitted to a newborn from the mother infected 20 years earlier. Am J Opthalmol. 2003;136(2):370–371. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(03)00191-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garweg JG, Scherrer J, Wallon M, Kodjikian L, Peyron F. Reactivation of ocular toxoplasmosis during pregnancy. BJOG. 2005;112:241–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Howe DK, Sibley LD. Toxoplasma gondii comprises three clonal lineages: correlation of a parasite genotype with human disease. J Infect Dis. 1995;172:1561–1566. doi: 10.1093/infdis/172.6.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rothova A, Buitenhuis HJ, Meenken C. Therapy of ocular toxoplasmosis. Int Ophthalmol. 1989;13:415–419. doi: 10.1007/BF02306491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holland GN, Lewis KG. An update on current practices in the management of ocular toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;134:102–114. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(02)01526-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Holland GN. Ocular toxoplasmosis: A global reassessment. Part II: Disease manifestations and management. LX Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;137(1):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ugwumadu A, Reid F, Hay P, et al. Natural history of bacterial vaginosis and intermediate flora in pregnancy and effect of oral clindamycin. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:114–119. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000130068.21566.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramsey PS, Vaules MB, Vasdev GM, et al. Maternal and transplacental pharmacokinetics of azithromycin. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:714–718. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGready R, Stepniwska K, Edstein MD, et al. The pharmacokinetics of atovaquone and proguanil in pregnant women with acute falciparum malaria. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2003;59:545–552. doi: 10.1007/s00228-003-0652-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tabbara KF, O’Connor GR. Ocular tissue absorption of clindamycin phosphate. Arch Ophthalmol. 1975;93:1180–1185. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1975.01010020882011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothova A, Bosch-Driessen LEH, van Loon NH, Treffers WF. Azithromycin for ocular toxoplasmosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1306–1308. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.11.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stray-Pedersen B. Treatment of toxoplasmosis in the pregnant mother and newborn child. Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1992;84:23–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez CE, Zhang D, Conway MD, Peyman GA. Successful management of ocular toxoplasmosis during pregnancy using combined intraocular clindamycin and dexamethasone with systemic sulfadiazine. Int Ophthalmol. :1998–1999. 22, 85–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1006129422690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gay-Andrieu F, Marty P, Pialat J, Sournies G, Drier de Laforte T, Peyron F. Fetal toxoplasmosis and negative amniocentesis: necessity of an ultrasound follow-up. Prenat Diagn. 2003;23(7):558–560. doi: 10.1002/pd.632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]