Abstract

Background and objectives: Two HALT PKD trials will investigate interventions that potentially slow kidney disease progression in hypertensive autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) patients. Studies were designed in early and later stages of ADPKD to assess the impact of intensive blockade of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and level of BP control on progressive renal disease.

Design, settings, participants, and measurements: PKD-HALT trials are multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials studying 1018 hypertensive ADPKD patients enrolled over 3 yr with 4 to 8 yr of follow-up. In study A, 548 participants, estimated GFR (eGFR) of >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 were randomized to one of four arms in a 2-by-2 design: combination angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) and angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy versus ACEi monotherapy at two levels of BP control. In study B, 470 participants, eGFR of 25 to 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 compared ACEi/ARB therapy versus ACEi monotherapy, with BP control of 120 to 130/70 to 80 mmHg. Primary outcomes of studies A and B are MR-based percent change kidney volume and a composite endpoint of time to 50% reduction of baseline estimated eGFR, ESRD, or death, respectively.

Results: This report describes design issues related to (1) novel endpoints such as kidney volume, (2) home versus office BP measures, and (3) the impact of RAAS inhibition on kidney and patient outcomes, safety, and quality of life.

Conclusions: HALT PKD will evaluate potential benefits of rigorous BP control and inhibition of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system on kidney disease progression in ADPKD.

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) is the most common inherited kidney disease occurring in 1/400 to 1/1000 live births and accounts for ∼4.6% of the prevalent kidney replacement population in the United States (1,2). ADPKD is a systemic disorder characterized by early onset hypertension before loss of kidney function. Hypertension relates to progressive kidney enlargement and is a significant independent risk factor for progression to ESRD (3).

As kidney cysts enlarge, kidney architecture and vasculature are compressed, resulting in interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy. Despite cyst growth and kidney enlargement, kidney function remains intact for decades. However, once GFR begins to decrease, a progressive decline in kidney function occurs, with 50% of patients requiring renal replacement therapy by age 53 yr (4,5).

MR imaging can accurately and reproducibly measure kidney volume and small changes in total kidney volume over short periods of time in ADPKD (6–8). Imaging studies in early ADPKD indicate that >90% show significant kidney enlargement (4 to 5%/yr), while renal function remains intact (6,8). In The Consortium of Radiologic Imaging Study of ADPKD (CRISP), hypertensive ADPKD patients showed a greater increase in kidney volume compared with normotensives with normal renal function (6.4 versus 4.3%/yr) (9). However, a causal role for hypertension in accelerated kidney growth in ADPKD cannot be proven from this observational cohort. The Polycystic Kidney Disease Treatment Network (HALT PKD) will directly test whether BP has a causal role in increased kidney volume in ADPKD.

The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) plays a role in the pathophysiology of hypertension and is activated in ADPKD patients (10–14). Some (12,13), but not all (14), have found higher plasma renin and aldosterone levels and a more pronounced decrease in renal vascular resistance after administration of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEi) in ADPKD compared with essential hypertensives. Angiotensin II is an important growth factor for kidney epithelial and interstitial fibroblasts, indicating that the RAAS may play also a role in cyst growth and expansion and kidney fibrosis. With increasing cyst size, activation of the RAAS occurs, BP increases, and a vicious cycle ensues with enhanced cyst growth, hypertension, and more cyst growth, ultimately leading to ESRD.

There are multiple randomized controlled trials in kidney disease addressing the impact of inhibition of RAAS on disease progression using ACEi that include ADPKD subjects (4,15–22). To date, no benefit of inhibition of the RAAS has shown benefit on progression to ESRD or rate of GFR decline (7). Importantly, a meta-analysis of 142 ADPKD subjects from eight trials in nondiabetic kidney disease reported a 25% nonsignificant relative risk reduction in the composite endpoint of ESRD or doubling of serum creatinine in individuals on ACEi compared with other anti-hypertensive agents (19). The meta-analysis also noted that most enrolled ADPKD subjects had late-stage disease, with a mean age of 48 yr and a mean baseline serum creatinine of 3.0 mg/dl. Overall, past studies have been limited by small numbers of patients who have been studied at relatively late stages of disease.

Renal chymase, which locally activates angiotensin II through non-ACE pathways, is elevated in ADPKD kidneys (23). Systemic angiotensin II levels do not suppress with chronic ACEi therapy in ADPKD, suggesting that non–ACEi dependent activation of the RAAS exists in ADPKD. Systemic and renal hemodynamic responses to exogenous angiotensin I and II persist in the presence of ACEi therapy in ADPKD (24,25). Additionally, although angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) therapy prevents the action of angiotensin II in systemic and renal circulations by binding with the angiotensin type 1 II receptor, angiotensin II levels increase with chronic ARB therapy and exogenous angiotensin II responses are also not totally suppressed (24,25). Therefore, if angiotensin II levels are important in regulating BP and renal plasma flow as well as promoting cyst growth in ADPKD, combination therapy with ACEi and ARB may be warranted.

On this background, the HALT-PKD trials, constituting two concurrent multicenter randomized placebo controlled trials have been initiated to compare the impact of rigorous versus standard BP control as well as combined ACEi + ARB therapy versus ACEi monotherapy on progression in both early and later stage ADPKD. This report will present the study design and rationale for these trials.

Materials and Methods

HALT PKD includes four participating clinical centers (PCCs), three satellite clinical sites, and a data coordinating center (DCC). The HALT-PKD steering committee is comprised of the Committee Chair and Vice Chair, the principal investigators of the PCCs and the DCC, and NIH/NIDDK project scientists. The PCCs include University of Colorado Health Sciences, Tufts Medical Center with Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center; Mayo College of Medicine with Kansas University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic; and Emory University. An external advisory committee has been established by NIH/NIDDK to review the study protocols before implementation and to provide trial oversight as the Data and Safety Monitoring Board after trial implementation. HALT-PKD began enrolling subjects in 2006 and concluded enrollment in mid-2009. Follow-up will continue in studies A and B until 2013 and 2014, respectively.

Organization of the HALT-PKD Trials

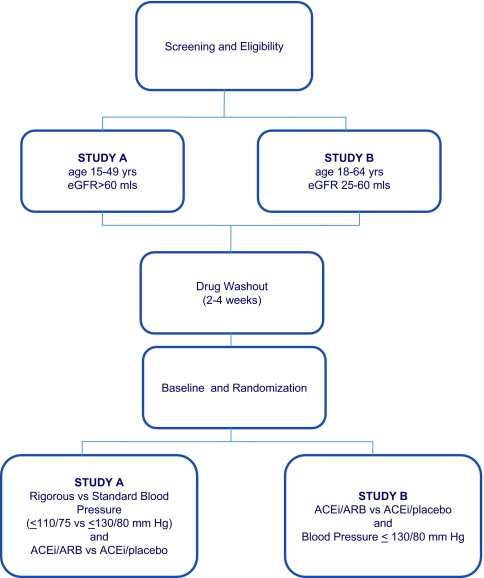

The HALT PKD trials are prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter interventional trials (Studies A and B; Figure 1; Table 1) using the same stepwise intervention. The trials will test whether multilevel blockade of the RAAS using ACEi + ARB (lisinopril + telmisartan) combination therapy will delay progression of renal disease versus ACEi (lisinopril + placebo) monotherapy in studies A and B and whether low BP control will delay progression compared with standard control in study A. Standard BP control for this study is defined as 120 to 130/70 to 80 mm Hg and low BP as 95 to 110/60 to 75 mm Hg.

Figure 1.

Organization of HALT A and B Studies.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for enrollment into HALT study A and B

| Inclusion Criteria |

| Age 15 to 49 yr for study A; age 18 to 64 yr for study B |

| GFR > 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, equated from serum creatinine using the four-variable MDRD equation (study A), GFR 25 to 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, equated from serum creatinine using the four-variable MDRD equation (study B) |

| Hypertension or high–normal blood pressure |

| Informed consent. |

Exclusion Criteria

|

Eligibility criteria for both HALT PKD trials are shown in Table 1. All eligible participants were able to undergo informed consent with a diagnosis of ADPKD based on Ravine's criteria (26). In the absence of a family history, a diagnosis of ADPKD was based on the presence of at least 20 kidney cysts bilaterally with features consistent with ADPKD. The presence of hypertension or high-normal BP is defined as a systolic BP of ≥130 mmHg and/or a diastolic BP of ≥80 mmHg on three separate readings within the past year or current use of anti-hypertensive agents for BP control (27). In study A, at baseline, subjects are 15 to 49 yr, with estimated GFR (eGFR) of >60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, whereas in study B, subjects are 18 to 64 yr, with eGFR 25 to 60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (28).

All subjects undergo a formal screening visit to verify eligibility and enrollment and assignment to study A or study B, based on eGFR. Subjects are randomly assigned to a treatment group by the DCC before the start of drug washout.

Home BP Measurements

Participants are trained at the screening visit to perform home BP measurements at least every other day during the drug washout period. BP measurements are obtained at least 30 min after awakening but before eating breakfast, smoking, or consuming caffeine. The participant sits quietly for at least 5 min, with the arm resting at heart level, and then obtains three BP readings at least 30 s apart. The average of the second and third seated measurements is used for decision making. If the difference between the last two systolic or diastolic readings was >10 mmHg, participants record a fourth and fifth reading, and the average of the last four readings is used.

For those taking anti-hypertensive medications, existing anti-hypertensives were gradually discontinued, and a 2- to 4-wk drug washout period was completed. Labetalol or clonidine was given during the washout period unless otherwise indicated for BP control. BP drugs taken for nonhypertensive indications were continued at the discretion of the principal investigator.

Participant Baseline and Randomization Procedures

Participants returned to the PCC for randomization within 10 wks of the screening visit and were randomized centrally by the DCC in equal proportions to combined lisinopril + telmisartan or lisinopril + placebo using random permuted blocks with stratification by PCC, participant age, gender, race, and baseline eGFR. Study A patients were additionally randomized in equal proportions to either a standard BP (120 to 130/70 to 80 mmHg) or low BP (95 to 110/60 to 75 mmHg) target.

Baseline and subsequent PCC visits are carried out in standardized fashion, including serum creatinine measurements (see below), biochemical assessments, complete history and physical examinations, MRI acquisitions in study A patients, clinic BP measurements (see below), and completion of 24-h urine collections for albumin and aldosterone excretion determinations, as well as health-related questionnaires. Baseline health status is assessed using the Medical Outcomes Study Short Form 36 Questionnaire, a self-reporting questionnaire that assesses physical, mental, and social aspects of health-related quality of life. A separate HALT PKD Pain Questionnaire is administered to capture the impact of pain, progressive kidney disease, and adherence to interventions (e.g., low BP) on mental and physical components of health.

Office (PCC) BPs are measured at the PCC: three times while seated and once while standing. The participant is seated quietly in a chair for a minimum of 5 min, with feet on the floor and the arm supported at heart level. Three measurements are taken in the appropriate arm, with a wait of at least 30 s occurring between each measurement. If there is >10 mmHg difference in systolic or diastolic BP, the last two readings are repeated. On completion of three seated BP measurements, the average of the last two readings is calculated. The participant stands for 3 min with his/her arm supported at heart level, and one BP measurement is taken. Height and weight are measured at every PCC visit to allow for calculation of body mass index.

Two blood samples, drawn a minimum of 1 h apart, are sent to the central laboratory (Cleveland Clinic Foundation Reference Laboratory) for analysis and to establish the baseline serum creatinine measurement. Consistency of the two serum creatinine measurements (<20% variation) is required. If the two measurements differ by >20%, a second set of serum creatinine samples is obtained shortly after and sent for repeat analysis.

A 24-h urine collection is performed at baseline, at the end of drug titration, and annually in HALT studies A and B. Adequacy of the collection is confirmed based on lean body weight for age and gender (29). Urinary sodium, potassium, creatinine, albumin, and aldosterone excretions are determined at Diagnostic Laboratory Facility at Brigham and Women's Hospital, Boston, MA.

MR imaging is performed in study A patients for the determination of total kidney volume, total liver cyst volume, left ventricular mass, and renal blood flow (30). MR images are obtained at each PCC using a protocol developed by the HALT PKD Imaging Subcommittee. After acquisition, MR images are reviewed locally and transferred securely, through the World Wide Web, to the Image Analysis Center at the University of Pittsburgh (31).

Randomization occurs at the baseline visit after all study procedures are completed and acceptable serum creatinine values are completed. Subjects are assigned to combined ACEi + ARB therapy or ACEi monotherapy and matched placebo [Aptuit (Greenwich, CT) provided packaging of active drug (manufactured by Novartis, East Hanover, NJ)]. Study drugs and additional open-label anti-hypertensive agents are distributed to participants at the baseline visit and are added in a stepped fashion as needed (Table 2). Study drug(s) are adjusted over time through both PCC and telephone visits.

Table 2.

Stepped dose titrations and second, third, and fourth line agents used in HALT study A and B

| Steps | Treatment | Control |

|---|---|---|

| Study A | ||

| 1–4 | Combination ACEi/ARB | Combination ACEi/Placebo |

| Lisinopril 5 mg/Telmisartan 40 mg | Lisinopril 5 mg/Placebo 40 mg | |

| Lisinopril 10 mg/Telmisartan 40 mg | Lisinopril 10 mg/Placebo 40 mg | |

| Lisinopril 20 mg/Telmisartan 80 mg | Lisinopril 20 mg/Placebo 80 mg | |

| Lisinopril 40 mg/Telmisartan 80 mg | Lisinopril 40 mg/Placebo 80 mg | |

| 5 | Hydroclorothiazide 12.5 mg qd | Hydroclorothiazide 12.5 mg qd |

| 6–8 | Metoprolol 50 mg BID | Metoprolol 50 mg BID |

| Metoprolol 100 mg BID | Metoprolol 100 mg BID | |

| Metoprolol 200 mg BID | Metoprolol 200 mg BID | |

| ≥9 | Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (diltiazem), clonidine, minoxidil, hydralazine at discretion of investigator | Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (diltiazem), minoxidil, clonidine, hydralazine at discretion of investigator |

| Study B | ||

| 1–4 | Combination ACEi/ARB | Combination ACEi/Placebo |

| Lisinopril 5 mg/Telmisartan 40 mg | Lisinopril 5 mg/Placebo 40 mg | |

| Lisinopril 10 mg/Telmisartan 40 mg | Lisinopril 10 mg/Placebo 40 mg | |

| Lisinopril 20 mg/Telmisartan 80 mg | Lisinopril 20 mg/Telmisartan 80 mg | |

| Lisinopril 40 mg/Placebo 80 mg | Lisinopril 40 mg/Placebo 80 mg | |

| 5 and 6 | Furosemide 20 mg BID | Furosemide 20 mg BID |

| Furosemide 40 mg BID | Furosemide 40 mg BID | |

| 7–9 | Metoprolol 50 mg BID | Metoprolol 50 mg BID |

| Metoprolol 100 mg BID | Metoprolol 100 mg BID | |

| Metoprolol 200 mg BID | Metoprolol 200 mg BID | |

| ≥10 | Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (diltiazem), clonidine, minoxidil, hydralazine at discretion of investigator | Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (diltiazem), minoxidil, clonidine, hydralazine at discretion of investigator |

Dose Titration and Study Maintenance

During the dose titration phase, home BP measurements are obtained every third day until BP goals are reached. Before subsequent PCC visits, home BP monitoring is performed twice a day for a minimum of 10 measurements over 14 d to determine BP target achievement. All adjustment in dosage of study drugs and addition of other anti-hypertensive agents is based on the home BP recordings.

Serum potassium, creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) are measured 1 wk after each dose increment. Follow-up telephone visits take place after each 2-wk period following medication adjustment and addressed these results, home BP records, and adverse events.

Once a BP target is reached, patients are evaluated through PCC and telephone visits. BP readings are recorded by the participant each month. After reaching the target BP goal, study coordinators contact participants by telephone at 3-mo intervals between clinic visits. During each telephone follow-up visit, unscheduled medical encounters, hospitalizations, and start of dialysis or transplantation are reviewed. Follow-up PCC visits during the first year of HALT PKD took place at 4, 7, and 12 mo after the start of therapy and subsequently every 6 mo until the end of the study. Patients in study A are followed until their 48-mo visit is completed. Follow-up visits in study B continue until the 60-mo visit has been performed for the last randomized participant, with an average patient follow-up of 6.5 yr.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes in HALT A and B Studies

In study A, the primary outcome of interest is the percent change in kidney volume as assessed by MRI at baseline 24 and 48 mo. In study B, the primary outcome is a composite endpoint of time to either 50% reduction of baseline eGFR, ESRD (initiation of dialysis or preemptive transplant), or death. Secondary endpoints for both studies include the rate of change of albuminuria and 24-h urinary excretion of aldosterone. In addition, the frequency of all-cause hospitalizations, hospitalizations because of cardiovascular events, quality of life, and pain, the frequency of PKD-related symptoms, and adverse effects of study medications are secondary outcomes for both studies. In study A only, the rate of change in GFR, renal blood flow, and left ventricular mass by MRI are also secondary outcomes.

PKD1 and PKD2 genetic mutation will be determined by direct sequencing and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification assay (32,33). We anticipate that mutations will be identified in ∼90% of cases and that ∼85% of detected mutations will be in PKD1. The information on genotype will be included in the overall analysis of outcomes for the study.

Primary Analyses

In study A, the primary endpoint variable is change in total kidney volume. Analysis of these data use random regression methods (34) incorporating a 2 by 2 design. A contrast comparison of the slopes of the random regression lines between low and standard BP control groups and between those on ARB compared with placebo will use log transformation of kidney volume for analysis. The overall slope is determined using three time points (35). In both comparisons, covariates including age, gender, race, genotype, baseline eGFR, and the participating clinical center are included. An interim analysis will be performed to determine whether interaction between the level of BP control and blockade of RAAS is an important issue for study A.

In study B, the primary outcome is a composite endpoint of time to either 50% reduction of baseline eGFR, ESRD, or death. Participants will be followed until the end of the study (4 to 6 yr). The analysis method will use survival methods and right censoring to account for those who do not reach the endpoint. The distribution of time-to-event is summarized by Kaplan-Meier product limit estimators. Proportional hazards (Cox) methods for comparison of survival times with censored observations are used to compare the difference between the two arms (36). Covariates similar to study A are included in study B analyses. To address the existence of both acute and chronic effects of RAAS inhibition (37), two samples (>2 h apart) for serum creatinine determinations will be drawn at baseline and at the end of drug titration (fourth month). If a different slope is suggested in the initial few months, the values from end of titration will be used as the initial kidney function measurement for analysis. For secondary outcomes, the effects of the treatment factors on the secondary outcomes will be tested at a significant level of 0.05 (two-tailed). Logistic regression will be used to assess the association between treatment factors and adverse events of study medication.

The primary analysis of both studies A and B will use an intent-to-treat strategy, with subjects included in their randomized groups regardless of their compliance with assigned treatments. During both studies, two interim analyses of efficacy are planned in addition to the final analysis (38).

To compute the necessary sample size/power, we estimated an average rate of change in total kidney volume, the SD of the slopes across participants, and the SD around the linear trajectories for each participant. Looking at the main effects and using the method of Lefante (39) and kidney volume at baseline and 2 and 4 yr, the necessary sample size (each group) for various effect sizes for a powers of 0.80 and 0.90, with a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed), is calculated.

In study A, with no interaction between the four cells, the calculated requisite sample size of 466 is found to have 90% power of detecting a 25% reduction from 5.4 to 4.1%/yr change in total kidney volume for subjects treated with lisinopril + telmisartan, with a significance level of 0.05 (two-tailed). Assuming a 15% loss of follow-up information on enrolled subjects, the target sample size for study A is 548 participants.

In study B, power estimates are based on an analysis of change in serum creatinine values in 134 ADPKD cases from the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) study whose initial GFR values are in the same range as the proposed HALT study B. The ACEi monotherapy control group is assumed to have the rate of decrease in eGFR values seen in MDRD and the ACEi/ARB group to have a rate slower than MDRD. The Laird and Ware model (40) is used for these data, with a mean intercept of 349. The average slope was −4.1 ml/min per year with a SD for the intercepts of 8.57 and 0.1956 for the slopes. The residual SD (40) is 2.1836. Using a Monte Carlo simulation of study B participants, we used an estimate slope range of −0.25 to 0.35 ml/min per month. When an eGFR at any visit was <50% of baseline for that simulated participant, an endpoint is declared. The rate of reaching endpoints is compared in the two groups using a log-rank test. The average 6-yr survival rate (life table method) is calculated as an average hazard rate. With this design, there is >0.90 power with 435 subjects to detect a slowing in the rate of change of eGFR by 25%. With a 15% dropout rate, a total of 470 (235 in each group) is needed for adequate enrollment in study B.

Discussion

The design of HALT-PKD studies A and B addresses several issues needed for the conduct of large multicenter trials, including the selection of an appropriate drug intervention, selection of an appropriate stage of kidney disease where an intervention may be most effective, and selection of study endpoints that are readily defined and ascertainable. Decisions made in the final design of interventional studies such as HALT-PKD reflect balancing scientific relevance and feasibility related to study duration and available resources. By having two studies in early and late ADPKD, benefits gained from a positive intervention for either study will translate into years of life gained without dialysis in this population.

Although a benefit of chronic ACEi or ARB therapy in slowing disease progression in ADPKD has not been established, current standards of care for treatment of hypertension and chronic kidney disease have invariably relied on ACEi therapy for preservation of kidney function (41). Moreover, ACEi and/or ARB therapy is frequently used by clinicians treating ADPKD patients in the absence of data defining a specific impact on this disease. Although it is possible that a difference in HALT-PKD patients will not be detected in those receiving ACEi + placebo versus ACEi + ARB, establishing disease progression in hypertensive ADPKD patients undergoing standardized inhibition of the RAAS will be extremely informative to provide data-driven evidence-based standards of care to the medical and patient community. In view of the absence of safety data with the frequently used combination ACEi + ARB therapy in clinical practice, the safety data collected in HALT-PKD will be particularly valuable. To this end, with the recent question of the COOPERATE trial (42–44) and the recently reported increased adverse event rates when using combination ACEi and ARB therapy versus ACEi alone without benefit seen in the ONTARGET (Ongoing Telmisartan Alone and in Combination With Ramipril Global End Point Trial) study (45), the HALT studies are crucial to address the question of maximal inhibition of the RAAS in ADPKD specifically and in chronic kidney disease in general.

Work from the CRISP and SUISSE studies validate that kidney volume can be accurately and reliably measured in ADPKD which, unlike serum creatinine levels, significantly associates with symptoms and loss of renal function in ADPKD (6,46). To assess therapies inhibiting RAAS and targeting level of BP control in ADPKD before measurable loss of kidney function when therapeutic benefits may be greatest, MR-based total kidney volumes may provide an accurate structural measure and potential surrogate measure for progressive kidney disease. This is the first interventional study in ADPKD to determine the benefits of therapy based on the structural endpoint of percent change in total kidney volume.

The composite endpoint of time either to death, ESRD, or 50% reduction in eGFR selected for study B is commonly used for trials in chronic kidney disease. Because the late stages of ADPKD are associated with more rapid loss of kidney function, which can be measured reliably in a multicenter trial, serum creatinine–based measures of kidney function are therefore included as a primary endpoint for study B. Using a time-to-event analysis, the composite endpoint also incorporates other hard endpoints that are relevant and readily ascertained in patients with significant kidney disease. These other parameters in the composite endpoint include the development of ESRD (need for dialysis or kidney transplant) and death. The extended follow-up for study B, 8 yr after enrollment initiation and 5 yr after enrollment termination, will provide the longest and largest longitudinal follow-up of an ADPKD cohort in the context of an interventional trial.

HALT-PKD is the first large multicenter interventional trial of ADPKD that is testing both a novel kidney structural endpoint in early disease (study A) and more conventional kidney functional endpoint in late disease (study B), using the same RAAS blockade therapeutic intervention. The design of two concurrently running studies in HALT-PKD addressed several issues unique to the natural history of this disease and will influence the design of future trials in ADPKD. Most important, potential benefits gained from a positive intervention for either study A or study B will translate into years of dialysis-free life in this population.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

The HALT-PKD study is supported by cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (DK62408, DK62401, DK62410, DK62402, and DK62411), the NCRR GCRCs at each institution (RR000039 Emory, RR000051 Colorado, RR00585 Mayo, RR000054 Tufts Medical Center, and RR23940 Kansas), and the NCRR CTSAs at each institution (RR025008 Emory, RR025780 Colorado, RR024150 Mayo, RR025752 Tufts, and RR024992 Washington University). Study medication for both trials was provided by Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals (telmisartan and matched placebo) and Merck & Co. (lisinopril). The Polycystic Kidney Disease Foundation provided financial support and recruitment assistance for the enrollment phase of HALT-PKD. The investigators thank Gigi Flynn and Robin Woltman and all of the clinical coordinators at each clinical site for their perseverance and hard work in implementing HALT-PKD.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.U.S. Renal Data System: Annual Data Report: Atlas of Chronic Kidney Disease and End-Stage Renal Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parfrey PS, Bear JC, Morgan J, Cramer BC, McManamon PJ, Gault MH, Churchill DN, Singh M, Hewitt R, Somlo S, et al. : The diagnosis and prognosis of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 323: 1085–1090, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabow PA, Johnson AM, Kaehny WD, Kimberling WJ, Lezotte DC, Duley IT, Jones RH: Factors affecting the progression of renal disease in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 41: 1311–1319, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klahr S, Breyer JA, Beck GJ, Dennis VW, Hartman JA, Roth D, Steinman TI, Wang SR, Yamamoto ME: Dietary protein restriction, blood pressure control, and the progression of polycystic kidney disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 2037–2047, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Churchill DN, Bear JC, Morgan J, Payne RH, McManamon PJ, Gault MH: Prognosis of adult onset polycystic kidney disease re-evaluated. Kidney Int 26: 190–193, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Bae KT, King BF, Jr, Wetzel LH, Baumgarten DA, Kenney PJ, Harris PC, Klahr S, Bennett WM, Hirschman GN, Meyers CM, Zhang X, Zhu F, Miller JP: Volume progression in polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 354: 2122–2130, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grantham JJ, Chapman AB, Torres VE: Volume progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: The major factor determining clinical outcomes. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 1: 148–157, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kistler AD, Poster D, Krauer F, Weishaupt D, Raina S, Senn O, Binet I, Spanaus K, Wuthrich RP, Serra AL: Increases in kidney volume in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease can be detected within 6 months. Kidney Int 75: 235–241, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chapman A, Grantham JJ, Guay-Woodford LM, Torres VE, Bae KT, Miller JP, Meyers CM: Progression of Renal Disease in Hypertensive (HBP) ADPKD Subjects Utilizing MR: The CRISP Consortium. J Am Soc Nephrol 16: 359A, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schrier RW: Renal volume, renin-angiotesin-aldosterone system, hypertension and left ventricular hypertrophy in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 20: 1888–1893, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres VE, Donovan KA, Scicli G, Holley KE, Thibodeau SN, Carretero OA, Inagami T, McAteer JA, Johnson CM: Synthesis of renin by tubulocystic epithelium in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 42: 364–373, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torres VE, Wilson DM, Burnett JC, Jr, Johnson CM, Offord KP: Effect of inhibition of converting enzyme on renal hemodynamics and sodium management in polycystic kidney disease. Mayo Clin Proc 66: 1010–1017, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman AB, Johnson A, Gabow PA, Schrier RW: The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. N Engl J Med 323: 1091–1096, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doulton TW, Saggar-Malik AK, He FJ, Carney C, Markandu ND, Sagnella GA, MacGregor GA: The effect of sodium and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition on the classic circulating renin-angiotensin system in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease patients. J Hypertens 24: 939–945, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maschio G, Alberti D, Janin G, Locatelli F, Mann JF, Motolese M, Ponticelli C, Ritz E, Zucchelli P: Effect of the angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor benazepril on the progression of chronic renal insufficiency. The Angiotensin-Converting-Enzyme Inhibition in Progressive Renal Insufficiency Study Group. N Engl J Med 334: 939–945, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The GISEN Group (Gruppo Italiano di Studi Epidemiologici in Nefrologia): Randomised placebo-controlled trial of effect of ramipril on decline in glomerular filtration rate and risk of terminal renal failure in proteinuric, non-diabetic nephropathy. Lancet 349: 1857–1863, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nutahara K, Higashihara E, Horie S, Kamura K, Tsuchiya K, Mochizuki T, Hosoya T, Nakayama T, Yamamoto N, Higaki Y, Shimizu T: Calcium channel blocker versus angiotensin II receptor blocker in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephron Clin Pract 99: c18–c23, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schrier R, McFann K, Johnson A, Chapman A, Edelstein C, Brosnahan G, Ecder T, Tison L: Cardiac and renal effects of standard versus rigorous blood pressure control in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: Results of a seven-year prospective randomized study. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1733–1739, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jafar T, Stark P, Schmid C, Strandgaard S, Kamper A, Maschio G, Becker G, Perrone RD, Levey ASACE Inhibition in Progressive Renal Disease (AIPRD) Study Group: The effect of angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors on progression of advanced polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 67: 265–271, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeltner R, Poliak R, Stiasny B, Schmieder RE, Schulze BD: Renal and cardiac effects of antihypertensive treatment with ramipril vs metoprolol in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 573–579, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson ML, Macnicol AM, Allan PL, Wright AF: Effects of angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition in adult polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 41: 206–210, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Dijk MA, Breuning MH, Duiser R, van Es LA, Westendorp RG: No effect of enalapril on progression in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 18: 2314–2320, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McPherson EA, Luo Z, Brown RA, LeBard LS, Corless CC, Speth RC, Bagby SP: Chymase-like angiotensin II-generating activity in end-stage human autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 493–500, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stepniakowski KT, Gerron GG, Chapman AB: Dissociation between systemic, adrenal, and renal response to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibition (Enalapril (En) 20 mg/day), angiotensin receptor blocker (Losartan (Los) 50 mg/day) vs combination therapy (En/Los) in subjects with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (PKD) during equimolar intravenous angiotensin I (Ang I) and angiotensin II (Ang II) infusion. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 507a–508a, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stepniakowski KT, Gerron GG, Chapman AB: Basal systemic, adrenal and renal responses to angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (Enalapirl (En) 20 mg), angiotensin receptor blocker (Losartan (Los) 50 mg) vs. combination therapy in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (PKD). J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 508a, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravine D, Gibson RN, Walker RG, Sheffield LJ, Kincaid-Smith P, Danks DM: Evaluation of ultrasonographic diagnostic criteria for autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease 1. Lancet 343: 824–827, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 289: 2560–2572, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levey A, Greene T, Kusek JW, Beck GJ: A simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine. J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 155A, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Walser M: Creatinine excretion as a measure of protein nutrition in adults of varying age. J Parenter Enteral Nutr 11: 73S–78S, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.King BF, Torres VE, Brummer ME, Chapman AB, Bae KT, Glockner JF, Arya K, Felmlee JP, Grantham JJ, Guay-Woodford LM, Bennett WM, Klahr S, Hirschman GH, Kimmel PL, Thompson PA, Miller JP: Magnetic resonance measurements of renal blood flow as a marker of disease severity in autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease. Kidney Int 64: 2214–2221, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moore SM, Maffitt DR, Blaine GJ, Bae KT: Workstation acquisition node for multicenter imaging studies. In: Medical Imaging 2001: PACS and Integrated Medical Information Systems: Design and Evaluation, edited by Siegel EL, Huang HK.San Diego, International Society of Optical Engineering, 2001, pp 271–277 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rossetti S, Consugar MB, Chapman AB, Torres VE, Guay-Woodford LM, Grantham JJ, Bennett WM, Meyers CM, Walker DL, Bae K, Zhang QJ, Thompson PA, Miller JP, Harris PC: Comprehensive molecular diagnostics in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 2143–2160, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Consugar MB, Wong WC, Lundquist PA, Rossetti S, Kubly VJ, Walker DL, Rangel LJ, Aspinwall R, Niaudet WP, Ozen S, David A, Velinov M, Bergstralh EJ, Bae KT, Chapman AB, Guay-Woodford LM, Grantham JJ, Torres VE, Sampson JR, Dawson BD, Harris PC: Characterization of large rearrangements in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease and the PKD1/TSC2 contiguous gene syndrome. Kidney Int 74: 1468–1479, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prentice RL, Williams J, Peterson AV: On the regression analysis of multivariate failure time data. Biometrika 68: 373–379, 1981 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Seber GAF, Wild CJ: Nonlinear Regression, New York, John Wiley & Sons, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Anderson PK, Gill RD: Cox's regression model for counting processes: A large sample study. Ann Stat 10: 1100–1120, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ryan MJ, Tuttle KR: Elevations in serum creatinine with RAAS blockade: Why isn't it a sign of kidney injury? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 17: 443–449, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lan KK, DeMets DL: Changing frequency of interim analysis in sequential monitoring. Biometrics 45: 1017–1020, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lefante JJ: The power to detect differences in average rates of change in longitudinal studies. Stat Med 9: 437–446, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laird NM, Ware JH: Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 38: 963–974, 1982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT, Jr, Roccella EJ: The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: The JNC 7 report. JAMA 289: 2560–2572, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakao N, Yoshimura A, Morita H, Takada M, Kayano T, Ideura T: Combination treatment of angiotensin-II receptor blocker and angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor in non-diabetic renal disease (COOPERATE): A randomised controlled trial. Lancet 361: 117–124, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kunz R, Friedrich C, Wolbers M, Mann JF: Meta-analysis: Effect of monotherapy and combination therapy with inhibitors of the renin angiotensin system on proteinuria in renal disease. Ann Intern Med 148: 30–48, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kunz R, Wolbers M, Glass T, Mann JF: The COOPERATE trial: A letter of concern. Lancet 371: 1575–1576, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Halimi JM, Mimran A: ONTARGET: does dual blockade of the renin-angiotensin system provide more effective cardiovascular and renal protection in patients at high cardiovascular risk? Curr Hypertens Rep 11: 85–87, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Serra AL, Kistler AD, Poster D, Struker M, Wuthrich RP, Weishaupt D, Tschirch F: Clinical proof-of-concept trial to assess the therapeutic effect of sirolimus in patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease: SUISSE ADPKD study. BMC Nephrol 8: 13, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]