Abstract

Background and objectives: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) lacks standardized patient safety indicators (PSIs); however, undetected safety events are likely to contribute to adverse outcomes in this disease. This study sought to determine the proportion of CKD patients who experience multiple potentially hazardous events from varied causes and to identify risk factors for the occurrence of “multiple hits.”

Design, setting, participants, & measurements: A sample of patients with CKD (n = 70,154) in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) were retrospectively examined for the occurrence of one or more safety events from a set of indicators defined a priori, including Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) PSIs, hypoglycemia, hyperkalemia, and dosing for selected medications not accounting for CKD.

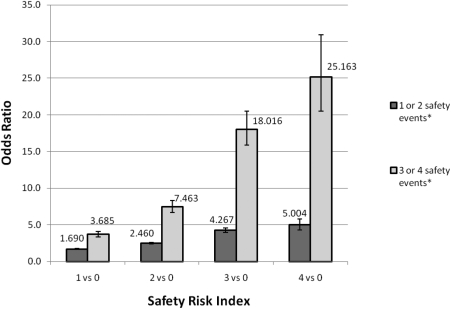

Results: Approximately half of the cohort participants experienced one or two adverse safety events, whereas 7% had three or four (multiple) distinct events. Individuals with three or four of the predesignated safety events were more likely to be diabetic, non-Caucasian, have an estimated GFR (eGFR) < 30 ml/min/1.73 m2, and be ≤65 yr of age. A “Safety Risk Index” was developed using these characteristics, and those subjects that had all four traits were 25 times as likely to have three or four adverse safety events versus those with none of the characteristics.

Conclusions: Patients with CKD are at a high risk for safety events pertinent to this disease and a substantial number are subject to multiple events from a diverse set of safety indicators, which could have important consequences in disease outcomes.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is increasing in prevalence in the United States (1), and patients with CKD are susceptible to adverse outcomes that may be linked to the delivery of care (2). The array of such potentially harmful events—often called safety events—in CKD includes those typically described for the general population as well as several others specific to this disease state. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)-defined set of patient safety indicators (PSIs) has been shown to be an effective tool for monitoring and tracking safety events in the general hospitalized population (3,4). Broadening the set of potential safety measures to include events pertinent to inpatient and ambulatory care in CKD is likely to increase the detection of harmful safety events in this disease.

We hypothesize that a broader set of safety measures in CKD will increase the probability of detecting potentially harmful safety events, and that there is an increased likelihood of multiple distinct events in any given individual with the disease. We defined a set of distinct safety indicators (AHRQ-defined PSIs, hypoglycemia, hyperkalemia, and select medications with inappropriate dosing) to be measured in a large sample of persons with CKD. The objective was to determine the proportion of the study population who experienced one or more of these predesignated safety events and to identify the risk factors for those individuals who suffered from multiple distinct safety events.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The study was a retrospective observational cohort study of a national sample of patients from the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) that was observed during the fiscal year 2005 (October 1, 2004 to September 30, 2005).

Setting and Data Sources

The setting and data sources used for this study have been previously described (2). Data were drawn from VHA fiscal year 2005 acute inpatient data files linked to the outpatient encounters, outpatient laboratory data, outpatient pharmacy data, and vital status files. The source data files included the Patient Treatment File, the Outpatient Care File, the Decision Support System Laboratory Result files, and the Pharmacy Benefits Management files (5,6). The Institutional Review Board of the University of Maryland–Baltimore and the Research and Development Committee of the Maryland VA Healthcare System approved this study.

Participants

The study population was taken from prior studies of veterans examined for adverse patient safety events associated with CKD (2,7,8). Patients had at least one acute care hospitalization during the study period, an outpatient measure of serum creatinine from 1 wk to 1 yr before hospitalization, and demographic information to determine estimated GFR (eGFR) and CKD classification. The creatinine value closest to the qualifying hospital admission was used, and index eGFR was calculated with the Modified Diet in Renal Disease equation to determine CKD status (9). To be included in the study, participants had to have at least stage 3 CKD defined as an index eGFR <60 ml/min/1.73 m2 (10). Patients with normal renal function were not included because they would not be at risk for medication dosing errors on the basis of a reduced GFR. Study participants had to have at least one inpatient or outpatient glucose and potassium measurement during the study period. Only the first hospitalization per patient that occurred in acute care facilities (index hospitalization) was included, because the AHRQ's PSIs were only developed and meant for identification of adverse events in acute care facilities.

To determine if study results were influenced by inclusion of patients receiving dialysis or not taking the preselected medications, we conducted sensitivity analyses on a reduced data set excluding patients with an index eGFR <10 ml/min/1.73 m2 or who had no prescriptions for the four selected medications during the study period.

Variables

The primary outcome variable was the occurrence of three or four of the adverse safety events. The four safety events were defined as one or more selected AHRQ PSIs, hypoglycemia, hyperkalemia, and errors in prescription of the preselected set of medications.

The covariates used for this study included demographics with race categorized as Caucasian, African American, or other. The comorbidities included cancer (excluding nonmelanomatous skin cancer), diabetes, cardiovascular disease (CVD; a composite of cerebrovascular disease, myocardial infarction, and/or congestive heart failure), and the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI was modified to exclude cancer, diabetes, renal and CVD, which were considered separately. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9CM) was used to classify all comorbidities of interest from inpatient and outpatient diagnostic codes recorded in VHA records from October 1, 1999, the earliest data available, to the date of index hospitalization. Patients were also classified as whether they had a prescription for an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) and/or an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) within 30 d of a potassium value. The stage of CKD was determined from the index eGFR (11).

Measurements

Safety events were only counted once per category but were added cumulatively when occurring in each independent category; therefore, individuals could experience between zero and four events during the study period. Modification and use of the AHRQ PSIs in CKD has been described previously and were also used here (see Appendix) (2). The incidence of a hypoglycemic event was defined as a measure of serum glucose less than 70 mg/dl (7). Incidence of a hyperkalemic event was defined as a measure of serum potassium equal to or greater than 5.5 mEq/L (8). Outpatient and inpatient laboratory test results were considered for these events.

To determine the incidence of medication errors, four commonly prescribed drugs in CKD (allopurinol; atenolol; atenolol with chlorthiadone, digoxin, and glyburide; or glyburide with metformin) were selected that require dose adjustment with impaired renal function. These medications were selected because they are frequently used in the disease population and have appreciable risk of adverse effects if dosed inappropriately. An error was considered if the patient received a dose of any one of the four drugs in excess of the recommended dosage or in too short an interval for the GFR most closely preceding the prescription (12).

A “Safety Risk Index” was created using the more predictive factors for having multiple safety events. The Safety Risk Index ranged from a score of zero to four on the basis of the number of unweighted factors present in any given individual, including presence of baseline diabetes, index eGFR <30 ml/min/1.73 m2, non-Caucasian race, and age 65 yr or younger.

Statistical Methods

For descriptive analyses, we computed N (%) and used the χ2 test for categorical variables, and the mean ± standard error (SEM) with ANOVA to compare means of continuous variables. We used a binary logistic regression model to compute adjusted odds ratios of having three or four adverse safety events versus no more than two events. We also used a multinomial logistic regression to study the association of the Safety Risk Index with the trinomial outcome (no adverse event, one to two events, and three to four events). Analyses were done using SAS version 9 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Participants

We identified 71,156 patients with at least one acute hospitalization within the study period who had CKD (<60 ml/min/1.73 m2). A measure of serum glucose was available for 98.6% of those, and a serum potassium value was available for 99.6%, resulting in a final sample of 70,154 study participants. In the restricted data set used in sensitivity analyses, there were 30,687 cohort participants.

Descriptive Data

Demographic characteristics of study participants are enumerated in Table 1 according to each adverse safety event. Patients with a hyperkalemic event were more likely to be men, younger, non-Caucasian, use an ACEI and/or ARB, and to be comorbid with more severe CKD (stage 4 or 5) than patients without a hyperkalemic event. Similar demographic contrasts were found for those who had a hypoglycemic event, except those with cancer were statistically more likely to have a hypoglycemic event compared with those without cancer. Patients who experienced at least one PSI event were more likely to be older; non-Caucasian; and have baseline comorbidity, cancer, and more severe CKD (stage 4 or 5) compared with stage 3 and less likely to have CVD or use ACEI and/or ARB. No differences were found among those with or without diabetes. Patients with incorrect medication dosing were found to be male, younger, and Caucasian; use an ACEI and/or ARB; and have diabetes, CVD, and CKD (stage 4 or 5). Of the 18.9% of patients who had a medication error, the majority had only one incorrect medication dosing (87.5%). Only 11.6% had two incidents of incorrect medication dosing, and <1% of patients had three or more incorrect medication dosings.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in VHA CKD safety cohort classified by presence or absence of each predesignated safety indicator (n = 70,154)

| Patient Characteristic | Hyperkalemia |

Hypoglycemia |

PSI |

Incorrect Medication Dosing |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium <5.5 meq/L | Potassium ≥5.5 meq/L | P Value | Glucose ≥70 mg/dl | Glucose <70 mg/dl | P Value | No Events | One or More Events | P Value | No Errors or No Drug Exposure | One or More Errors | P Value | |

| Patients (row %) | 52,123 (74.3) | 18,031 (25.7) | 53,178 (75.8) | 16,976 (24.2) | 55,413 (79.0) | 14,741 (21.0) | 56,875 (81.1) | 13,279 18.9) | ||||

| Gender (column %) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.806 | <0.001e | ||||||||

| male | 50,248 (96.4) | 17,623 (97.7) | 51,307 (96.5) | 16,564 (97.6) | 53,605 (96.7) | 14,266 (96.8) | 54,916 (96.6) | 12,955 (97.6) | ||||

| female | 1875 (3.6) | 408 (2.3) | 1871 (3.5) | 412 (2.4) | 1808 (3.3) | 475 (3.2) | 1959 (3.4) | 324 (2.4) | ||||

| Race | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.008 | <0.001e | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 44,141 (84.7) | 13,978 (77.5) | 45,198 (85.0) | 12,921 (76.1) | 46,032 (83.1) | 12,087 (82.0) | 47,034 (82.7) | 11,085 (83.5) | ||||

| African American | 7459 (14.3) | 3810 (21.1) | 7432 (14.0) | 3837 (22.6) | 8790 (15.9) | 2479 (16.8) | 9251 (16.3) | 2018 (15.2) | ||||

| other | 523 (1.0) | 243 (1.3) | 548 (1.0) | 218 (1.3) | 591 (1.1) | 175 (1.2) | 590 (1.0) | 176 (1.3) | ||||

| Age (yr)a | 71.8 ± 0.09 | 70.1 ± 0.16 | <0.0001 | 71.8 ± 0.09 | 70.1 ± 0.16 | <0.0001 | 71.3 ± 0.09 | 71.6 ± 0.18 | 0.0032 | 71.5 ± 0.09 | 70.8 ± 0.17 | <0.0001e |

| ACEI/ARB | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001e | ||||||||

| none | 18,799 (36.1) | 5361 (29.7) | 19,158 (36.0) | 5002 (29.5) | 18,766 (33.9) | 5394 (36.6) | 20,856 (36.7) | 3304 (24.9) | ||||

| either | 31,748 (60.9) | 11,854 (65.7) | 32,452 (61.0) | 11,150 (65.7) | 34,753 (62.7) | 8849 (60.0) | 34,261 (60.2) | 9341 (70.3) | ||||

| both | 1576 (3.0) | 816 (4.5) | 1568 (2.9) | 824 (4.9) | 1894 (3.4) | 498 (3.4) | 1758 (3.1) | 634 (4.8) | ||||

| CCI | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001e | ||||||||

| 0 | 21,295 (40.9) | 6365 (35.3) | 21,544 (40.5) | 6116 (36.0) | 21,935 (39.6) | 5725 (38.8) | 22,226 (39.1) | 5434 (40.9) | ||||

| 1 | 19,684 (37.8) | 6823 (37.8) | 19,991 (37.6) | 6516 (38.4) | 21,043 (38.0) | 5464 (37.1) | 21,466 (37.7) | 5041 (38.0) | ||||

| 2+ | 11,144 (21.4) | 4843 (26.9) | 11,643 (21.9) | 4344 (25.6) | 12,435 (22.4) | 3552 (24.1) | 13,174 (23.2) | 2804 (21.1) | ||||

| Cancer | 0.275 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001e | ||||||||

| no | 37,710 (72.3) | 13,121 (72.8) | 38,281 (72.0) | 12,550 (73.9) | 40,326 (72.8) | 10,505 (71.3) | 41,002 (72.1) | 9829 (74.0) | ||||

| yes | 14,413 (27.7) | 4910 (27.2) | 14,897 (28.0) | 4426 (26.1) | 15,087 (27.2) | 4236 (28.7) | 15,873 (27.9) | 3450 (26.0) | ||||

| Diabetes | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.169 | <0.001e | ||||||||

| no | 27,762 (53.3) | 6985 (38.7) | 30,287 (57.0) | 4460 (26.3) | 27,520 (49.7) | 7227 (49.0) | 30,582 (53.8) | 4165 (31.4) | ||||

| yes | 24,361 (46.7) | 11,046 (61.3) | 22,891 (43.0) | 12,516 (73.7) | 27,893 (50.3) | 7514 (51.0) | 26,293 (46.2) | 9114 (68.6) | ||||

| CVD | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | <0.001e | ||||||||

| no | 25,349 (48.6) | 7438 (41.3) | 25,959 (48.8) | 6828 (40.2) | 25,743 (46.5) | 7044 (47.8) | 27,074 (47.6) | 5713 (43.0) | ||||

| yes | 26,774 (51.4) | 10593 (58.7) | 27,219 (51.2) | 10,148 (59.8) | 29,670 (53.5) | 7697 (52.2) | 29,801 (52.4) | 7566 (57.0) | ||||

| CKD stage | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001e | ||||||||

| 3b | 45,304 (86.9) | 11,875 (65.9) | 45,273 (85.1) | 11,906 (70.1) | 45,854 (82.7) | 11,325 (76.8) | 46,969 (82.6) | 10,210 (76.9) | ||||

| 4c | 4790 (9.2) | 3491 (19.4) | 5260 (9.9) | 3021 (17.8) | 6052 (10.9) | 2229 (15.1) | 6242 (11.0) | 2039 (15.4) | ||||

| 5d | 2029 (3.9) | 2665 (14.8) | 2645 (5.0) | 2049 (12.1) | 3507 (6.3) | 1187 (8.1) | 3664 (6.4) | 1030 (7.8) | ||||

Mean ± 1.96 SEM.

Stage 3 = 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 > GFR ≥ 30 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Stage 4 = 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 > GFR ≥ 15 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Stage 5 = GFR < 15 ml/min/1.73 m2.

P < 0.001.

Table 2 presents the cohort categorized based on number of distinct event categories experienced over the study period. Of note, approximately half of the cohort participants had one or two safety events, whereas 7% had three or four events. Patients who had three or four of the predesignated safety events (PSIs, hypoglycemia, hyperkalemia, and/or incorrect medication dosing) were more likely to be male, non-Caucasian, younger, use an ACEI and/or ARB, and have a higher CCI than patients who had fewer or no safety events. Diabetic patients had a 2.9 times greater odds of having three or four adverse safety events compared with nondiabetic patients. Patients with stage 5 CKD were 2.8 times more likely than patients with stage 3 CKD to have multiple safety events during the study period. Among patients with GFR <30, 14.2% had three or four safety events, whereas only 5.4% of patients with GFR in the range of 30 to 59 had three or four safety events (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients in VHA CKD safety cohort classified by number of distinct safety events

| Patient Characteristic | Adverse Patient Safety Eventsa | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zero Events | One or Two Events | Three or Four Events | Odds (OR)g of Having Three or Four Eventsb | |

| Patients (row %) | 30,081 (42.9) | 35,153 (50.1) | 4920 (7.0) | 70,154 (100.0) |

| Gender (column %) | ||||

| male | 28,883 (96.0) | 34,191 (97.3) | 4797 (97.5) | 1.00 |

| female | 1198 (4.0) | 962 (2.7) | 123 (2.5) | 0.91 (0.75, 1.09) |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 25,870 (86.0) | 28,467 (81.0) | 3782 (76.9) | 1.00 |

| African American | 3921 (13.0) | 6284 (17.9) | 1064 (21.6) | 1.17 (1.09, 1.26)h |

| other | 290 (1.0) | 402 (1.1) | 74 (1.5) | 1.26 (0.98, 1.61) |

| Age (yr)c | 71.9 ± 0.12 | 71.1 ± 0.12 | 69.6 ± 0.32 | 0.994 (0.991, 0.997)h |

| ACEI/ARB | ||||

| none | 11,595 (38.5) | 11,250 (32.0) | 1315 (26.7) | 1.00 |

| either | 17,716 (58.9) | 22,545 (64.1) | 3341 (67.9) | 1.27 (1.18, 1.36)h |

| both | 770 (2.6) | 1358 (3.9) | 264 (5.4) | 1.46 (1.27, 1.69)h |

| CCI | ||||

| 0 | 12,488 (41.5) | 13,368 (38.0) | 1804 (36.7) | 1.00 |

| 1 | 11,295 (37.5) | 13,379 (38.1) | 1833 (37.3) | 1.04 (0.97, 1.12) |

| 2+ | 6298 (20.9) | 8406 (23.9) | 1282 (26.1) | 1.20 (1.11, 1.30)h |

| Cancer | ||||

| no | 21,733 (72.2) | 25,419 (72.3) | 3679 (74.8) | 1.00 |

| yes | 8348 (27.8) | 9734 (27.7) | 1241 (25.2) | 1.01 (0.94, 1.08) |

| Diabetes | ||||

| no | 18,626 (61.9) | 14,948 (42.5) | 1173 (23.8) | 1.00 |

| yes | 11,455 (38.1) | 20,205 (57.5) | 3747 (76.2) | 2.88 (2.68, 3.08)h |

| CVD | ||||

| no | 15,276 (50.8) | 15,503 (44.1) | 2008 (40.8) | 1.00 |

| yes | 14,805 (49.2) | 19,650 (55.9) | 2912 (59.2) | 1.04 (0.98, 1.11) |

| CKD stage | ||||

| 3d | 27,068 (90.0) | 27,028 (76.9) | 3083 (62.7) | 1.00 |

| 4e | 2120 (7.0) | 5072 (14.4) | 1089 (22.1) | 2.34 (2.17, 2.52)h |

| 5f | 893 (3.0) | 3053 (8.7) | 748 (15.2) | 2.79 (2.55, 3.07)h |

Safety events include any of a PSI event, hyperkalemia, hypoglycemia, and/or an incorrect medication dosing.

As compared with having two or less safety events.

Mean ± 1.96 SEM.

Stage 3 = 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 > GFR ≥ 30 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Stage 4 = 30 ml/min/1.73 m2 > GFR ≥ 15 ml/min/1.73 m2.

Stage 5 = GFR < 15 ml/min/1.73 m2.

OR = odds ratio.

P < 0.001.

In the sensitivity analysis, the percentage of participants that had one or two events stayed the same (57.6%), whereas the proportion of veterans with CKD who had three or four events increased to 10.4%. Those factors that were associated with increased odds of three or four events remained the same.

The contingency table (Table 3) shows the frequency of concordance between the predefined safety indicators. More than half of persons who experienced a safety event from any of the predefined categories experienced an event from at least one of the others. The greatest concordance was between hyperkalemia and hypoglycemia: of those patients who had a hypoglycemic event, 45.1% also had a hyperkalemic event. The trends in concordance were comparable with the restricted data set in sensitivity analyses.

Table 3.

Contingency table demonstrating concordance of each predesignated safety indicator with others in VHA CKD safety cohort [40,073 (57.1%) had at least one event]a

| PSIb | Hypoglycemiac | Hyperkalemiad | Incorrect Medication Dosinge | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (% of entire cohort) | 14,741 (21.0) | 16,976 (24.2) | 18,031 (25.7) | 13,279 (18.9) |

| No other safety event (% of each indicator) | 5759 (39.1) | 5422 (31.9) | 5623 (31.2) | 5856 (44.1) |

| PSIb | – | 4629 (27.3) | 5829 (32.3) | 2854 (21.5) |

| Hypoglycemiac | 4629 (31.4) | – | 7659 (42.5) | 4121 (31.0) |

| Hyperkalemiad | 5829 (39.5) | 7659 (45.1) | – | 4024 (30.3) |

| Incorrect medication dosinge | 2854 (19.4) | 4121 (24.3) | 4024 (22.3) | – |

Percentages sum to greater than 100% because individuals can have more than one safety event.

PSI refers to one or more event occurring in the study period and includes all 20 AHRQ original PSIs plus 12 experimental and modified PSIs.

Hypoglycemia refers to a blood glucose measurement <70 mg/dl.

Hyperkalemia refers to a blood potassium measurement ≥5.5 meq/L.

Incorrect medication dosing refers to one or more such events occurring in the study period.

Safety Risk Index

A Safety Risk Index was used to discriminate those individuals at high risk for multiple events versus few or none. As individuals had sequentially more characteristics from the Safety Risk Index, they were at a higher risk of three or four adverse safety events than one or two, or when compared in either case to patients with none of these factors. Figure 1 depicts the odds of one or two events or three or four safety events versus no events in the presence of one or more of the safety risk factors. The odds of having one or two safety events increases with a greater number of safety risk factors; however, in each ordinal category of safety risk factors, the odds of three or four safety events exceed those associated with one or two events. The difference in risk for three or four events versus one or two is greatest in the group with all four safety risk factors. Also, no appreciable differences were noted in these trends with analysis of the restricted data set.

Figure 1.

Odds [odds ratio (OR)] of either few (one or two) or multiple (three or four) safety events versus none by number of safety risk index factors in VHA CKD safety cohort. *As compared with having zero safety events.

Discussion

We have shown that the incidence of assorted safety events pertinent to CKD is common in a sample of patients with this disease. The proportion of individuals who experience more than one such event is high, with a substantial number experiencing three or four types of distinct safety events within a 1-yr period. Using a simple safety risk factor index was useful in identifying those individuals in the disease population at risk for any safety event but was also helpful in outlining the portion of the population at risk for multiple such events. The finding of a high proportion of persons with CKD who experience multiple safety events underscores the exceptional vulnerability of this population to the potential adverse effects of medical care.

Patient safety events have costly consequences for patients and healthcare networks, increasing the length of stay, hospital readmissions, and the risk of death (2,4,7,8). Preventing these adverse events can improve quality of care and patient outcomes (13). Despite progress in improving care in targeted high-risk areas that threaten patient safety, (13) much work is needed in to improve safety in specific disease states such as CKD. This study builds upon widely used safety indicators developed for the general population and provides potential disease-specific measures for CKD.

Prior studies have helped define disease-specific PSIs related to CKD (2,7,8). Hospitalized patients with CKD are at markedly greater risk for having AHRQ-defined PSIs than patients without CKD (2). Hyperkalemic and hypoglycemic events were individually found to be common adverse safety events as well as risk factors for mortality in patients with CKD (7,8). Moreover, medication errors are a common finding in the hospitalized population with prevalent CKD (14). The AHRQ has suggested an expanded framework within which to consider patient safety such that it can be adapted to other disease states such as CKD (15). This study points out that patients with a complex disease such as CKD are at risk of an assortment of safety events beyond the scope of those previously considered.

There are important clinical implications from this study. First, the high frequency of diverse safety events observed reveals the specialized care needs of the CKD population. Second, it is possible that under-recognition of CKD contributed to the high frequency of safety events observed in this study and strategies that increase disease recognition may reduce the incidence of such events. Finally, the high incidence of safety events could contribute to the high rates of morbidity and mortality observed in patients with CKD.

Limitations

Analyses of large data sets have the potential for recording errors and missing information because the data were not collected for the purpose of the intended study. The safety indicators used might be considered somewhat arbitrary without appropriate validation and verification before their use; however, they were chosen a priori because of their expected high frequency and known relevance in CKD. Moreover we cannot be certain that a specific adverse event was a direct result of medical care and would have been otherwise preventable. Recognizing that our selection of medications for the study was limited, it is possible that if other medications that require renal adjustment were chosen, different frequencies of safety events would have been detected; however, the medications were selected for their common use in the disease population and ease of abstraction from VHA data sources. Additionally, there were a limited number of risk factors available for analysis, and it is likely that other factors when considered would improve the predictive models presented.

Finally, it is feasible that the cohort selected for the study was more prone to safety events than the broader CKD population because their severity of illness was such that they had increased encounters with the VHA (including at least on acute hospitalization). This could have lead to an overestimate of the incidence of safety mishaps as defined here. However it is important to note that this cohort is likely to be fairly representative of the CKD population at large, which has a high frequency of hospitalization. Moreover, our surveillance for events included not only in-hospital but also outpatient records when one would expect study subjects to be more closely aligned in complexity of illness with the broader CKD population.

In conclusion, patients with CKD are at an exceptionally high risk for assorted and multiple safety events pertinent to this disease population. It is imperative that a patient identified with CKD is monitored closely for medication dosages as well as other potential safety events that can be prevented. Improving the safety of CKD-specific patient care may help to reduce mortality and improve the quality of life of patients with this disease.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grant R21DK075675 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Appendix

AHRQ PSIs Used in the Study

Approved PSIs used in study presented here (see reference 2).

Complication of anesthesia

Death in low-mortality diagnosis-related groups

Decubitus ulcer

Failure to rescue

Foreign body left during procedure

Iatrogenic pneumothorax

Selected infections due to medical care

Postoperative hip fracture

Postoperative hemorrhage or hematoma

Postoperative physiologic and metabolic derangements

Postoperative respiratory failure

Postoperative pulmonary embolism or deep venous thrombosis

Postoperative sepsis

Postoperative wound dehiscence

Accidental puncture or laceration

Transfusion reaction

Additional experimental PSIs (see reference 2).

Physiologic and metabolic derangements in all diagnoses among all discharges

Aspiration pneumonia

Coronary artery bypass graft after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty

Postoperative in-hospital myocardial infarction

Technical difficulty with procedure

Dosage complications

Postoperative iatrogenic complications

Postoperative iatrogenic cardiac complications

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Coresh J, Selvin E, Stevens LA, Manzi J, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Levey AS: Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the united states. JAMA 298: 2038–2047, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seliger SL, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Fink JC: Chronic kidney disease adversely influences patient safety. J Am Soc Nephrol 19: 2414–2419, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen AK, Zhao S, Rivard P, Loveland S, Montez-Rath ME, Elixhauser A, Romano PS: Tracking rates of patient safety indicators over time: Lessons from the veterans administration. Med Care 44: 850–861, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedman B, Encinosa W, Jiang HJ, Mutter R: Do patient safety events increase readmissions? Med Care 47: 583–590, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cowper DC, Hynes DM, Kubal JD, Murphy PA: Using administrative databases for outcomes research: Select examples from VA health services research and development. J Med Syst 23: 249–259, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maynard C, Chapko MK: Data resources in the department of veterans affairs. Diabetes Care 27[Suppl 2]: B22–B26, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moen MF, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Einhorn LM, Seliger SL, Fink JC: Frequency of hypoglycemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1121–1127, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Einhorn LM, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Moen MF, Seliger SL, Weir MR, Fink JC: The frequency of hyperkalemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Arch Intern Med 169: 1156–1162, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levey AS, Greene T, Kusek JW, Beck GJ: A simplified equation to predict glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine [Abstract]. J Am Soc Nephrol 111: 115A, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS: Assessing kidney function-measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med 354: 2473–2483, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Kidney Foundation: K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: Evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis 39: S1–S266, 2002 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aronoff GR, Berns JS, Brier ME, Golper TA, Morrison G, Singer I, Swan SK, Bennett WM: Drug Prescribing in Renal Failure: Dosing Guidelines for Adults, 4th ed., Philadelphia, American College of Physicians, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr EA, Fleming B: Making performance indicators work: Experiences of U.S. Veterans Health Administration. BMJ 335: 971–973, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corsonello A, Pedone C, Corica F, Mussi C, Carbonin P, Antonelli Incalzi R: Gruppo Italiano di Farmacovigilanza nell'Anziano (GIFA) Investigators: Concealed renal insufficiency and adverse drug reactions in elderly hospitalized patients. Arch Intern Med 165: 790–795, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer GS, Battles J, Hart JC, Tang N: The US agency for healthcare research and quality's activities in patient safety research. Int J Qual Health Care 15[Suppl 1]: i25–i30, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]