Abstract

The population of Winnebago County in 1918 was approximately 62,000 residents. It consisted of towns supporting diverse manufacturers surrounded by farming country. For this study, records were revisited, and 1918 to 1920 influenza survivors were interviewed. A pharmacological investigation encompassing the various influenza treatments used in Wisconsin from 1918 to 1920 was documented. In 1918, over 180 individuals perished from influenza, and over 2000 cases were reported in Winnebago County, Wisconsin. Influenza returned in 1920, which some researchers refer to as the “fourth wave,” claiming nearly 50 lives in Winnebago County, Wisconsin. This study also documents the 1920 influenza wave.

Keywords: 1918, 1920, Influenza, Mortality, Pandemic, Spanish flu

The 1918 influenza (also termed la grippe or Spanish influenza) pandemic charged across America in seven days and across the world in three months. The number of deaths is speculative, perhaps as high as 100 million. The majority of researchers place the most credible upper limit at 50 million.1–7 It was associated with high rates of morbidity, mortality, social disruption, and high economic costs.

Its incubation period and the onset of symptoms were so short that apparently healthy people in the prime of their lives (ages 15 to 35) were suddenly overcome, and within an hour could become helpless with fever, delirium and chills. Additional symptoms were severe headache, pain in muscles and joints, hair loss, acute congestion, and temperatures of 101 F to 105 F.1–4 The most unusual pathologic finding was massive pulmonary edema and/or hemorrhage.1–4 This was a unique viral pneumonia – a patient could be convalescing one day and dead the next. Those who did not die of the 1918 influenza, often died of secondary bacterial pneumonia.1–5

There have been numerous studies considering how individual cities responded to the 1918 influenza pandemic, including Crosby’s writings of “Flu in Philadelphia” and “Flu in San Francisco” in America’s Forgotten Pandemic.2 However, documentation of the response of Midwestern and rural communities is lacking in the literature. This paper reports on how an entire county – Winnebago County, Wisconsin – located in a rural heartland part of the United States, responded to the 1918 and 1920 influenza epidemics.

METHODS

The 1918 to 1919 death records located at the Winnebago County Courthouse Office of Vital Records and Deeds were reviewed. A database listing each person in Winnebago County who died of the “Spanish influenza” during the epidemic was created. The database included other information such as age, location of death, contribution(s) toward death, nationality, occupation, sex, and place of burial. Results presented in graphical form do not include data from death certificates that only list pneumonia as the cause of death. In other words, the death certificate had to contain the word influenza or Spanish influenza in order to generate the graphical results in this report.

An exhaustive search was conducted. Many inquiries were made to the currently existing schools, cemeteries, hospitals, churches, libraries, police departments, and other leads to information. Archival materials were collected from the Wisconsin State Historical Society and University of Wisconsin Oshkosh Polk Library Archives. These materials included census records, naturalization records, newspapers, city directories, State Board of Health minutes, high school annuals, probate actions, maps, military records, and pharmacist ledgers, among other sources. Additional information about this collaborative cross-disciplinary study is described in Council on Undergraduate Research (CUR) Quarterly.8

Description of Winnebago County

Geographical Location, Industry, Farming and Transportation

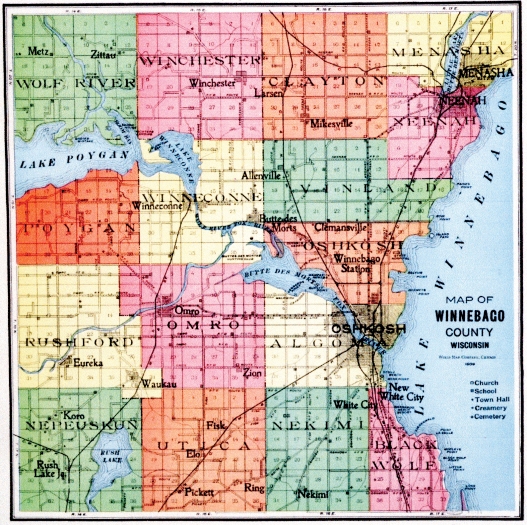

Winnebago County is located in east-central Wisconsin, and Oshkosh is the county seat. Oshkosh is located 88 miles north of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Its population in 1918 was 33,062. It is situated along the Fox River where it flows into Lake Winnebago and is the central city of the Fox River Valley, in contrast to the lower Fox River that flows into Lake Michigan (figure 1▶). The geographical location of Oshkosh meant that it functioned as an industrial distribution center.

Figure 1.

(A) 1909 Winnebago County, Wisconsin map published by Chicago World Map Company. Oshkosh (population 33,062 in 1910) is the central city of the Fox River Valley and county seat. The twin cities of Neenah and Menasha are located along the Fox River, 5 miles north of Oshkosh. Townships are displayed in different colors [Courtesy of UW-Oshkosh Polk Library Archives]; (B) Map of Wisconsin counties [Courtesy of US Census Bureau].

Hospitals, Schools, Newspaper, Telegraph and Telephone Communication

At the beginning of the 20th century, there were seven hospitals in and near the city of Oshkosh. There was a State cooperative laboratory in Oshkosh that worked in collaboration with the City Health Department to furnish laboratory tests to local physicians. There were 11 public schools, a new high school, a vocational school, and a Normal school (teaching college) in Oshkosh.

Newspapers mainly disseminated Winnebago County news. The Daily Northwestern was published in Oshkosh twice daily (morning and evening) and circulated to over 14,000 individuals. For most residents, it was the major source for news, and it reported the numbers of influenza cases and obituaries during the 1918 and 1920 influenza epidemics. The newspaper served as a source of information for this study; however, it should be noted that this resource has limitations regarding accuracy in its tally of influenza cases.

Western Union and postal telegraph companies were available day or night. The Wisconsin Telephone Company had 5,200 city phones in operation in Oshkosh and was connected to 850 farmer phones in the county. In 1918, there were approximately 33,000 local and 450 long distance calls made daily.9

State Board of Health Creation and Influenza Recommendations

In 1876, the Wisconsin legislature created the State Board of Health. This Board consisted of seven physicians charged with the responsibility of supervising the interests of health for all Wisconsin citizens. Wisconsin was the 10th state to create such a Board, the first being Massachusetts in 1869.10 The Board, along with a public health network, responded with a strong anti-influenza national program in 1918.1 Population densities and influenza’s later arrival likely gave the public health network an advantage by giving them more time to react.

At the local level, on October 5, 1918 (the first week of influenza cases in Oshkosh), the Oshkosh City Health Commissioner, Dr. A.H. Broche, urged physicians to report all cases of influenza and to isolate the patients, advised a public gathering ban, and urged enforcement of an anti-expectorant ordinance. Diagnosis of influenza was based on symptoms (eg, sudden fever accompanied by chills, shivering, headache and aching pains throughout the body, followed by the development of a sore throat and cough). Researchers in laboratories presumed the causative agent was a bacterium cultivated from the lungs of victims or possibly an unknown filterable virus. There were no research laboratories in Winnebago County.

Within one week, an isolation emergency hospital was ready for patients, and the commission council secured the horse-drawn ambulance to transport persons suffering from influenza in Oshkosh (figure 2▶). The Wisconsin State Board of Health recommendations were administered: (1) local health officers must report all influenza cases; (2) isolate influenza patients; and (3) quarantine influenza patients. An influenza placard was placed on the door of the residence of the infected individual(s).

Figure 2.

The Oshkosh city horse-drawn ambulance was reactivated in 1918 to transport influenza patients while the motorized ambulance was used to transport those with other illnesses [Reproduced with permission from the Oshkosh Public Museum, Oshkosh, Wisconsin. All rights reserved].

Of the 25 registered states, Wisconsin ranked 4th lowest in death rates (3.3/1000) from influenza and pneumonia from September 1918 to December 1918. The highest ranked state was Pennsylvania, which had a death rate of 7.3 deaths per 1000 individuals. The lowest was Michigan with 2.9 deaths per 1000.11 The average death rate for these registered states was 4.8 deaths per 1000.12

Historical Time Line: Progression of Influenza in Winnebago County, 1918

October 1918 Wave

The earliest personal record pertaining to influenza cases in Winnebago County occurs in the diary of Adolf O. Erickson, a hardware store owner and Sunday School teacher in Winchester township. He chronicles that Winchester resident “Nels Thorsen is not feeling well” on September 27, 1918, and that Winchester resident Emil Jones was still quite sick with influenza on September 30th (Erickson A., personal diary 1918, Winchester, WI). Nels Thorsen died on October 1, 1918. Erickson and his family attended the Thorsen funeral. No death certificate is present today for Thorsen at the Winnebago County Office of Vital Records and Deeds. Interestingly, Adolf Erickson’s family did not contract influenza until the middle of December 1918. His entire family became sick, yet all of them survived.

The best records available at the time document the 1918 influenza cases in the city of Oshkosh. About six weeks before the end of World War I, the Oshkosh Daily Northwestern stated on October 5, 1918, “Influenza has appeared here. City will fight to Control it.”13 Local physicians reported ten influenza cases to Oshkosh Police Chief Henry F. Dowling on this day. Dr. A.H. Broche, the City Health Commissioner, urged all doctors to isolate patients and report cases to Police Chief Dowling in order to appraise the situation.

Two days later, two individuals died from the 1918 influenza in Winnebago County. They were 19-year-old John Daniel Jones, Jr. and Bernhardt Mehlmann, a 37-year-old traveling notions salesman. John D. Jones Jr., an Oshkosh native, left home after his 18th birthday to find work in Belvidere, Illinois. After working in Belvidere for five months, Jones registered for the army and returned to Oshkosh for a military physical examination. When he arrived in Oshkosh on October 4, 1918, he was admitted to Mercy Hospital. He was pronounced dead on October 6, 1918. Dr. A.H. Broche completed his death certificate on October 8th, listing influenza and double lobar pneumonia as the contributors to death. Dr. Broche wrote on the death certificate that Jones’ influenza had been contracted in Belvidere, Illinois. As for Mehlmann, who died on October 7, 1918, there was never an obituary published about him in any Winnebago County newspaper, even though his death certificate provided an Oshkosh address for his residence. Neither Mehlmann nor his parents are listed in any Oshkosh city directories.9 His name could not be found in any U.S. Census records.

By October 8, 1918, newspaper articles mentioned that the “Views of doctors on how to handle grip don’t agree. All say situation is serious. Some urge prompt closing and quarantines.” This same day, the cases tallied 163 in Oshkosh.14 Weeden Drug Company began advertising in the Daily Northwestern for “Spanish flu” medicines and cures. By October 10th, a shortage of flowers was reported, with florists in the city of Oshkosh experiencing difficulty supplying the heavy demands for funerals.15

On October 10, 1918, the first order from Dr. C.A. Harper, the Wisconsin State Health Officer, advised an immediate closing of all schools, churches, Sunday Schools, theatres, moving picture houses, and other places of amusement and public gatherings for an indefinite time-period.16,17 On October 12, 1918, six clergymen posted an announcement to the Catholics of Oshkosh, ordering churches closed per the request of the health department and the State of Wisconsin.18

A delegation of women supporting prohibition from five different organizations waited outside City Hall and appealed to Mayor McHenry to close the Oshkosh saloons. Instead of closings, Mayor McHenry ordered a curfew on all saloons, pool halls, cafes, and restaurants to close by 5:00 pm each day in Oshkosh. Mayor McHenry stated that he did not want to discriminate against any class of business unless it was proven necessary by the state or federal governments.19

S.M.B. Hunt, chairman of the Oshkosh Chapter of the American Red Cross, received gauze “flu masks” from Red Cross Headquarters on October 12, 1918.20 Masks complied with the Board of Health’s recommendations to be three thicknesses of butter cloth or, if cheese-cloth was worn, eight thicknesses. On October 14th, an Isolation Hospital, also referred to as the Liberty Hospital, was ready to serve influenza patients who were transients or lived in home conditions that were unsuitable.21,22 The Oshkosh city government rented a house near the north edge of the city limits and converted it into an Emergency/Isolation Hospital. A horse-drawn ambulance was used to transport influenza patients to the Emergency Hospital. It was kept at the Isolation Hospital grounds. The motorized ambulance was used to transport those with other illnesses located at other hospitals. Scientists and physicians strived hard to find a therapy to treat this malady.

On October 22, 1918, a vaccine from the Mayo Foundation for Medical Examination and Research at Rochester, Minnesota was distributed to local physicians who desired protection for themselves from influenza and influenza-pneumonia. The vaccine formulation was credited to Dr. E.C. Rosenow. Three inoculations, each a week apart, were recommended for a period of six to nine months to “confer immunity.”23 Dr. Broche telegraphed for additional vaccine to be supplied “gratis” by the Mayo Foundation for study. Individuals inoculated were required to fill out questionnaires reporting the results of the vaccination (eg, documenting how many inoculations they had and whether or not they contracted influenza or influenza/pneumonia). Exact numbers of vaccinated individuals is unknown.24

By November 2, 1918, the spread of disease was under control and the number of new cases was decreasing. Oshkosh Mayor McHenry lifted the evening closing ban.25 Churches, moving picture houses, lodges, and theatres reopened. Schools, however, remained closed. The public library was opened after all books were fumigated. Election day, November 5, 1918, came and went, without a single political rally or campaign dinner.26

November 1918 Wave

At approximately 2 am on November 11, 1918, the Daily Northwestern office received word via an Associated Press telegram that the Armistice was signed.27 Ecstatic community members opened the curtains of their homes and made their way to the main street of the city. “Night shirt” parades were evident. Later in the day, there were parades in Oshkosh and Neenah.28 The crowds were huge. There was a victory dance and a peace service that night in Oshkosh. Unfortunately, this public mingling of crowds was favorable for transmitting the influenza virus, resulting in another wave of 1918 influenza transmission.

By November 14, 1918 the health department record indicated an increase in the number of 1918 influenza cases in Oshkosh.29 Mayor McHenry issued orders to Police Chief Dowling to rigidly enforce the “no spitting” ordinance because he believed it to be a contributing factor to the spread of influenza in the community.30 City Health Commissioner Broche ordered the influenza ban back into effect. The influenza ban was finally lifted on November 29, 1918, and Oshkosh schools reopened on December 3, 1918.

1920 Wave

Few authors have presented data describing the 1920 wave of influenza in the recent literature. A paper in 2002 by Johnson and Mueller7 updated the global mortality of the 1918 to 1920 Spanish influenza pandemic. They state that the pattern of age mortality can be considered one of the most important and identifying characteristics of this pandemic. According to Mueller and Johnson, the 1918 influenza seems to have persisted into or returned in 1920 in some locations, such as Scandinavia and in isolated South Atlantic islands.7 Interviews of 1918 influenza survivors alluded to an epidemic in Winnebago County in 1920. By revisiting official records, we were able to confirm that Winnebago County did experience another wave of influenza during January and February of 1920 that mimicked its predilection for the young and healthy as victims.

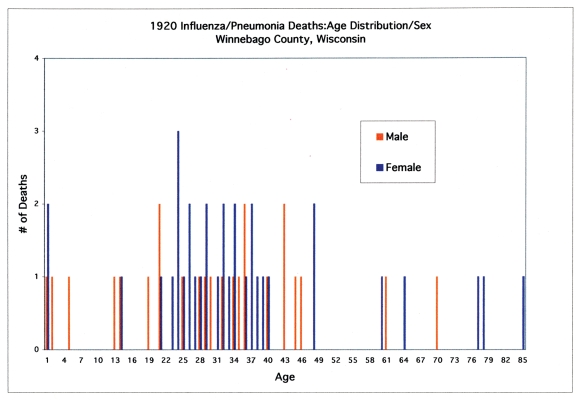

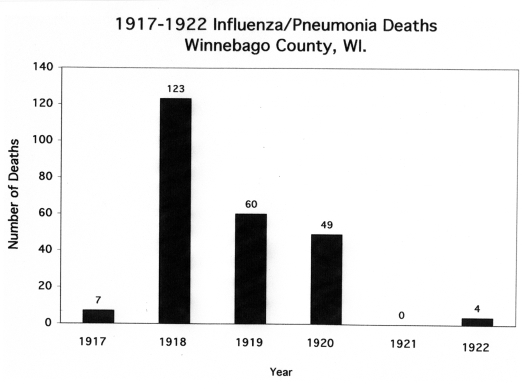

Several Winnebago County residents who survived the 1918 influenza epidemic were willing to be interviewed for our study. They spoke of influenza deaths that occurred in 1920. We confirmed that during the months of January and February 1920, there were 49 influenza-related deaths in Winnebago County; 31 of these were Oshkosh residents (figure 3▶). Figure 4▶ presents a histogram summarizing the influenza/pneumonia deaths in Winnebago County from 1917 to 1922.

Figure 3.

Age and sex distribution of 1920 influenza/pneumonia mortalities in Winnebago County, Wisconsin. The 1920 influenza virus caused the highest number of deaths in 19 to 40-year-olds with no preference toward males or females.

Figure 4.

Histogram summarizing the total number of deaths related to influenza in the years before, during and after the 1918 to 1920 epidemics. The graph clearly shows the increase in influenza mortalities in Winnebago County from 1918 to 1920.

The 1920 influenza outbreak also produced the same debilitating physical effects as in 1918, and affected mainly those individuals in the prime of their lives. It was contained to a two-month time period. Schools, amusement places, and churches did not close. Superintendent Manuel of the Oshkosh Northern Hospital for the Insane ordered the hospital closed to visitors.31 An Isolation Hospital was set up in Oshkosh. In 1920 it was located at the Old Jewell Homestead on the west side of the city.

How did Winnebago County Fare?

The 1918 influenza epidemic in Winnebago County spanned the time period from September 27, 1918 through May 31, 1919. The last newspaper tally stated that there had been 2,330 cases as of December 26, 1918.32 During this time period, 183 people died in Winnebago County; the majority (120 individuals) dying in October, November, and December of 1918. Of the 183 deaths, the numbers can be broken down into 116 Oshkosh residents, 30 Neenah residents, 16 Menasha residents, three individuals in each of the following townships: Omro, Wolf River, and Winchester, and two individuals each in Rushford, Nekimi, Utica, Black Wolf, Clayton, and Winneconne townships (figure 1A▶). Table 1▶ summarizes death rates and compares Winnebago County to counties of similar population in the state of Wisconsin. These rates were taken from the Wisconsin Report of the State Board of Health.11 Populations were recalculated based on their findings.

Table 1.

Deaths and death rates for 1918 to 1919 influenza in selected counties of Wisconsin.

| Number of deaths† | Death rate per 1,000† | Population‡ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| County* | 1918 | 1919 | 1918 | 1919 | 1918 | 1919 |

| Brown | 190 | 63 | 3.3 | 1.1 | 57,576 | 57,273 |

| Fond du Lac | 115 | 33 | 2.2 | 0.6 | 52,273 | 55,000 |

| Marathon | 93 | 62 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 62,000 | 62,000 |

| Racine | 295 | 56 | 4.3 | 0.8 | 68,605 | 70,000 |

| Sheboygan | 207 | 34 | 3.5 | 0.6 | 59,143 | 56,667 |

| Winnebago | 124 | 60 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 65,263 | 66,667 |

| State of Wisconsin | 7,066 | 2,230 | 2.8 | 0.9 | 2,523,571 | 2,477,778 |

*Counties chosen had a population within 20% of the population of Winnebago County based on the 13th Census of the United States.

†Data taken from the Report of the State Board of Health, Wisconsin, 1918–1920.

‡Population was calculated by the formula: number deaths/death rate per 1000 X 1000.

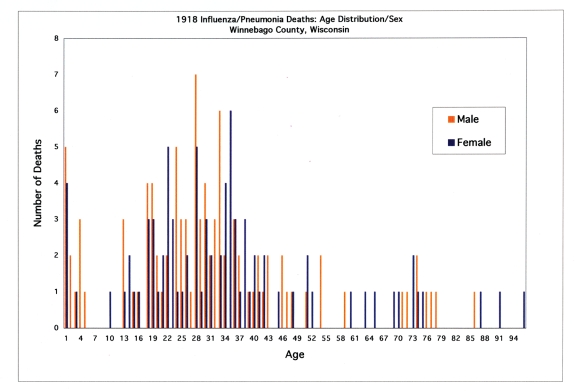

This study affirmed the age distribution of deaths reported by others, the peak being 15 to 35 year olds (figure 5▶). Of these deaths, 53% were males and 47% were females. These results are similar to previous findings.33–35

Figure 5.

Age and sex distribution of 1918 influenza/pneumonia mortalities in Winnebago County, Wisconsin. The 1918 influenza virus caused the highest number of deaths in 13 to 43- year-olds with no preference toward males or females.

It has been suspected that influenza infection is associated with fetal or perinatal mortality.36–42 A small epidemiological study by Stanwell-Smith et al36 suggested that there may be an association between influenza A and fetal death. We examined Winnebago County Death records (1916 to 1922).43 Over this time period, there were 233 deaths (137 males and 96 females) (results not shown). The average number of deaths for the years and months before and after the influenza epidemics was 2.6 deaths per month. During the eight months of the 1918 to 1919 influenza epidemic, the average number of premature/stillbirths was 4.25 per month. This is almost a 40% increase during these eight months, and is significantly higher than the surrounding months. Larger epidemiological studies will be needed to confirm association between influenza and fetal death.

Pharmacies and Medicines

Finding pharmacist records pertaining to Winnebago County was difficult for this time period. Because we were unable to locate any Winnebago County pharmacist records, we extended this part of our investigation to other communities in Wisconsin. With the help of the Wisconsin Historical Society, we located records kept by pharmacists in Steven’s Point, Portage and River Falls, Wisconsin (1918 records from Stout Pharmacy, daybook/ledger, Stevens Point, WI; Graham Drug Co., ledger of patients/prescriptions, Portage WI; Freeman Drug Co., financial records and formula books, River Falls, WI).

During the months of October through December 1918, physicians predominately prescribed heroine hydrochloride, codeine sulphate, cocaine hydrochloridum, opium, morphine sulphate, elixir terpin hydrate (a concoction of terpentine, alcohol, and nitric acid), paregoric elixir (made with powdered opium, benzoic acid, camphor, oil of anise, glycerin diluted alcohol, and morphine). The Dispensatory of the United States of America, a manual used by pharmacists, lists the uses of all of these drugs as a relief for cough and abdominal pain or as a sedative for the respiratory center.44 Adolf O. Erickson wrote that a physician injected eight shots of camphor oil directly into his brother’s legs and arms to treat the raging temperatures caused by the influenza (Erickson A., 1918 personal diary, Winchester, WI). The Domestic Health Society published Health Knowledge, A Thorough and Concise Knowledge of the Prevention, Causes, and Treatments of Disease, Simplified for Home Use in 1921.45 It defines Spanish Influenza as the “Three Day Fever” caused by Pfeiffer’s bacillus. Treatment recommendations were two to four doses of quinine of 5 grains each, one hour apart. People were urged to be given a hot mustard footbath and have a hot water bottle or hot iron at their feet. They were also told to drink plenty of hot lemonade or milk, and keep their bowels functioning by using Epsom salts.45 In addition, several recipes were recommended and are listed in table 2▶.

Table 2.

Spanish Influenza remedy recipes published in Health Knowledge.45

| Recipe | Ingredients |

|---|---|

| Remedy 1 | 48 grains Aspirin |

| 24 grains Phenacetine | |

| 48 grains Salol | |

| Mix, and make into 12 capsules | |

| Dose: One capsule every 3 hours | |

| Remedy 2 | 15 grains Acetanilid |

| 75 grains Aspirin | |

| Mix, and make into 15 powders | |

| Dose: One powder every 4 hours, with a little water | |

| Dried Raspberries | Boil 1 tablespoon of dried raspberries in 2 teaspoonfuls of water. Boil 10–15 minutes, strain, and drink as hot as can be tolerated. It can be sweetened if preferred. Repeat every 3–4 hours. |

| Camphor | Add 15–20 drops of spirits of camphor in a teacup of hot water. Drink as hot as possible, especially on going to bed. Repeat every hour or two. |

| Cayenne Pepper | Add one teaspoonful of cayenne pepper to boiling water. Boil for 10 minutes covered, then strain through a fine cloth. Add one teaspoonful of this fluid to a teacupful of hot water. Repeat every hour or two. |

Many advertisements appeared in the local press for influenza remedies. They included patent medicines such as Snake Oil, Laxative Bromo-Quinine, Smoko Tobaccoless Cigarettes, Vick’s Vaporub, Hinckle’s Tablets, “77” colds, Kondon’s Catarrhal Jelly, Horlick’s Malted Milk, Kraft’s Preventative Powder, Laudanum (a tincture of opium), Essence of Peppermint, Spirits of Camphor, Extract Witch Hazel, and Musterole laxative cold tablets (containing acetanilid). Compounds containing acetanilid were used in medicine chiefly as an analgesic or antipyretic. Blackberry brandy was advertised and allowed for sale without a license. Other patent medicines advertised included Dr. Bell’s Pine Tar Honey, Hamlinz Wizard Oil, Cascara Quinine (Hill’s Bromide), and a famous old recipe for cough syrup that listed Pinex as the major ingredient. Pinex is a highly concentrated compound of Norway pine extract that was known for its healing effect on membranes. Catarrh Snuff was guaranteed to give relief against colds/influenza. In 1920, Talnac, a patented medicine comprised of beneficial herbs and roots, was the most advertised drug claiming to prevent the influenza by providing powerful resistance to infection.

Many of the aforementioned drugs prescribed by physicians for the Spanish influenza were controlled substances such as heroine, codeine, cocaine, opium and morphine. The Dispensatory of the United States of America did note the potential hazards of these drugs in its description of uses.44 Few pharmacists would sell more than an ounce of these drugs because of their habit-forming potential. Many remedies contained a large percentage of alcohol (1918 records from Stout Pharmacy, daybook/ledger, Stevens Point, WI; Graham Drug Co., ledger of patients/prescriptions, Portage WI; Freeman Drug Co., financial records and formula books, River Falls, WI).

Interestingly, some of the patented medicines contained compounds derived from phenol, such as salol and phenacetin (para-acetamidophenetol). Salol was prepared by heating salicylic acid with phenol in the presence of phosphorous pentchloride or phosphorous oxychloride yielding 35% phenol, 64% salicylic acid.45 It was considered to be an internal antiseptic and was often prescribed in treating influenza. Phenacetin was used as a pain relieving drug. It was prepared by distilling phenol and subsequently reducing it with hydrochloric and glacial acetic acid. Acetanilid was derived by heating alinine in glacial acetic acid and used as an antipyretic or analgesic.45 The concentrations of phenol used during this time period were very high.

Vick’s Vaporub, a proprietary combination of menthol, camphorated oil, eucalyptus oil and terpentine oil, has passed the test of time. It is used today to relieve nasal and catarrhal congestion associated with colds/influenza. Pine oil (which was used in some remedies), turpentine, and camphor oil belong to a group of chemicals called terpenes. All terpenes are local irritants. Ingestion produces gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, aspiration, and pulmonary toxicity. Absorption is associated with alteration in mental status, ranging from coma to seizures. Renal and liver toxicity has been reported.46 Following ingestion, pine oil may be concentrated in the lungs, resulting in chemical pneumonitis without evidence of aspiration. In 1983, the FDA required that the concentration of camphor in products not exceed 11%.47 In summary, it appears that some of the ingredients used in influenza home remedies, patent medicines, and prescriptions used in 1918 are still used today but in much lower (safer) concentrations.

Other Lessons Learned

Record Keeping

This study represents a re-examination of the effects of the 1918 and 1920 influenza epidemics on a typical Midwestern county. Over 180 individuals perished from the 1918 influenza in this county and over 2000 cases were reported in Winnebago County, Wisconsin. Limited records remain today.

Physicians reported all cases to the city health departments. Subsequently, local health officers reported all influenza cases to the Chief of Police in a community; however, none of these records exist at the police departments. The police departments relayed case information to local newspapers, and during the height of the epidemics, the Oshkosh Daily Northwestern did include stories broadcasting the number of cases. There are no hospital records available to indicate how many patients were treated for influenza during the period of 1918 to 1920 in Winnebago County. The Wisconsin Register of Reports of Contagious Diseases recorded that there were 100 cases of influenza in Winnebago County during November 1918. This report listed no cases in December 1918.48 This demonstrates the under-reporting that occurred during the epidemic.

In 1920, a Report of the Wisconsin State Board of Health was published by the Homestead Company in Madison, Wisconsin.12 This document did not report numbers of cases. Rather, it reported the number of influenza deaths in Wisconsin counties from 1918 to 1920. These numbers match our study.

By examining the epidemic in Winnebago County, one senses the demands on county officials. For example, 1918 influenza death records from the Northern State Hospital for the Insane were filed as much as three months late during this time period. In addition, another 46 deaths were probably related to influenza (these death records listed such contributions to death as edema of the lungs, suggesting the unique 1918 influenza). Hence, some local physicians had difficulty diagnosing the disease or contributing factors toward the cause of death for some individuals.

Healthcare

The diary of Adolf O. Erickson, Winchester township, chronicles one person’s view of the role of physicians, nurses and clergy during the 1918 influenza epidemic. (Erickson A., 1918 personal diary, Winchester, WI). A physician from Neenah, along with a nurse, visited Jahner Olsen, Erickson’s neighbor in Winchester, once or twice daily through December 22, 1918. A nurse cared for Olsen during the day for over a week. One adult remained awake all night to watch over Olsen as well. Reverend A.O.B. Moldrum visited him on December 13th, during the height of his illness. Erickson states that Olsen had a temperature ranging from 103 F to 105 F for seven days (December 11th to 18th). On December 15th, a physician administered four shots of camphor oil into each of his arms and legs. The next day, he administered four more shots, two in the left arm and two in the left leg. Erickson recorded that he had phone conversations with local physicians at odd hours (eg, 2 am). His writings demonstrate the dedication of local physicians, nurses, clergy, and family in caring for the sick. A 1918 influenza survivor that we interviewed reiterated this by saying, “I can still see the old doctor’s face; he made rounds all night long” (Jelinske HA, personal communication and written family histories, Stories of …Life’s Winding Pathways and Once Upon a Lifetime).

University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh psychology students collected oral histories from the 1918 and 1920 influenza survivors. The interviews repeatedly confirmed that the doctors in their towns were heroes; they were beloved. The memories of these now very old people were poignant. They described the symptoms of the 1918 influenza pandemic that have been documented in the literature: raging fever, chills, coughing up blood, vomiting, gasping for air, shivering, burning eyes, and hair loss, among other symptoms characteristic of the 1918 influenza outbreak (Jelinske HA, personal communication and written family histories, Stories of …Life’s Winding Pathways and Once Upon a Lifetime; Keefe KM. An Oral History of the 1918 Influenza Epidemic. Unpublished results).

CONCLUSION

Our study of the 1918 and 1920 influenza epidemic in one county in Wisconsin reveals a portrait of people doing their best to respond to the most widespread public health crisis ever experienced in the United States. We found that public officials and medical professionals coped well, using the knowledge and medicines available to them at the time. For the most part, the people of Winnebago County cooperated with the quarantine and helped their neighbors, while suffering losses of family members and friends. The vivid memories of older people late in the 20th century, when they reflected back on this pandemic in the early years of the century, testified to the impact it had on the community.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Elizabeth Prine (Riverside Cemetery Study) and Mr. Joshua Ranger (Polk Library Archives) for their invaluable contributions. Graduate students, Tina Schneider (epidemiology statistics) and Kristy M. Keefe (compilation of oral histories), contributed significantly to this manuscript. In addition, the authors thank undergraduates, Eric Stanelle (1918 influenza folk medicines), and Marie Gabavics and Heather Wichman (1920 influenza wave), for their independent research. The authors thank all of the students at UW-Oshkosh and members of the community (1918 to 1920 influenza survivors) who participated in this study. The authors wish to give special mention to influenza survivors Helen Jelinske and Eleanor Vein for sharing their influenza experiences and stories. This study is dedicated to the late Helen Jelinske, a former UW-Oshkosh alumnus and 1918 influenza survivor. She was 8-years-old, living in a rural area outside of Oconto during the 1918 Spanish flu outbreak. Her insight and memories, in particular her self-published histories, Stories of …Life’s Winding Pathways and Once Upon a Lifetime, were a major driving force of this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Burg S. The Spanish Flu, 1918. Wisconsin Magazine of History; State Historical Society of Wisconsin 2000; Autumn:36–56. [PubMed]

- 2.Crosby A. America’s forgotten pandemic. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1989.

- 3.Reid AH, Taubenberger JK,. Fanning TG. The 1918 Spanish influenza: integrating history and biology. Microbes Infect 2001;3:81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mamelund SE. Spanish influenza mortality of ethnic minorities in Norway 1918–1919. Eur J Pop 2003;19:83–102. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taubenberger J, Morens D. The 1918 Influenza: the mother of all pandemics. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12:15–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Webster R, Bean W, Chambers T, Kawaoka Y. Evolution and ecology of influenza A viruses. Microbiol Rev 1992; 56:152–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johnson NP, Mueller J. Updating the accounts: global mortality of the 1918–1920 “Spanish” Influenza pandemic. Bull Hist Med 2002;76:105–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shors T, McFadden SH. Facilitated learning through interdisciplinary undergraduate research involving retrospective epidemiological studies and memories of older adults. CUR Quarterly 2009;30:36–41. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Konrad’s Oshkosh City Directory including Omro and Winneconne. Milwaukee, WI: Wright Directory Co. Publishers; 1919.

- 10.Wisconsin Blue Book. Wisconsin Historical Society. Madison, WI: Democratic Printing Board; 1903. Available at: http://digital.library.wisc.edu/1711.dl/WI.WIBlueBks.

- 11.State Board of Health Telegram from C. A. Harper. 1918. Records of the Wisconsin Board of Health: Eau Claire Research Center; Eau Claire, WI.

- 12.Report of the Wisconsin State Board of Health. 1918–1920. 57–58. Records of the Homestead Co.; Madison, WI.

- 13.Influenza has appeared here. City will fight to control it. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. October 5, 1918:3.

- 14.Views of doctors on how to handle Grip don’t agree. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. Evening, October 8, 1918:10.

- 15.Shortage in flowers. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. October 10, 1918:3.

- 16.To close schools to guard against spread of germs of the Influenza, The Daily Northwestern, October 8, 1918:3.

- 17.Sweeping Order Closes Places of Public Sort to Check Germs, The Daily Northwestern, October 9, 1918:3.

- 18.Rev. AL Bastian, Rev. JC Hogan, Rev. AS Krause, Rev. MJ Schmitz, Rev. JA Selbach, Rev. MH Clifford. Announcement: To the Catholics of Oshkosh. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. Evening, October 12, 1918:3.

- 19.Mayor is visited to ask for close of the saloons. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. Evening, October 12, 1918:3.

- 20.“Flu” masks ready to check epidemic. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. October 12, 1918:1.

- 21.Hospital Nearly Ready. The Daily Northwestern, October 11, 1918:4.

- 22.Now Has Patients. The Daily Northwestern, October 14, 1918:7.

- 23.Vaccine on hand to prevent “Flu.” The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. October 22, 1918:3.

- 24.Eyler JM. The fog of research: influenza vaccine trials during the 1918–19 pandemic. J Hist Med Allied Sci 2009; 64:401–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Closing ban to be lifted next Monday in this city. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. November 2, 1918:3.

- 26.Influenza lid lifted Friday The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. November 7, 1918:1.

- 27.Oshkosh got up early to show joy at the good news. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. November 11, 1918:8.

- 28.Peace parade big. It is also noisy, ideas are clever. Spirits run high. The Daily Northwestern, November 12, 1918:10.

- 29.New “Flu” cases 38. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. November 14, 1918:10.

- 30.Get after spitters. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. No vember 15, 1918:14.

- 31.Closed to visitors. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. January 26, 1920:4.

- 32.Epidemic is getting weak. Snow and cold weather are said to have been the antidote. The Daily Northwestern. Oshkosh, WI. December 27, 1918:10.

- 33.Collins SD. Age and sex incidence of influenza and pneumonia morbidity and mortality in the epidemic of 1928–29 with comparative data for the epidemic of 1918–19. Public Health Reports 1931;33:1909–1937. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simonsen L, Clarke MJ, Schonberger LB, Arden NH, Cox NJ, Fukuda K. Pandemic versus epidemic influenza mortality: a pattern of changing age distribution. J Infect Dis 1998;178:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ammon CE. Spanish flu epidemic in 1918 in Geneva, Switzerland. Euro Surveill 2002;7:190–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stanwell-Smith R, Parker AM, Chakraverty P, Soltanpoor N, Simpson CN. Possible association of influenza A with fetal loss: investigation of a cluster of spontaneous abortions and stillbirths. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev 1994;4:R28–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schubert A. [The incidence of abnormalities after flu epidemics.] [Article in German] Z Arztl Fortbild (Jena). 1992;86:935–937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madec F, Kaiser C, Gourreau JM, Martinat-Botte F. [Pathologic consequences of a severe influenza outbreak (swine virus A/H1N1) under natural conditions in the non-immune sow at the beginning of pregnancy.] [Article in French] Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis 1989;12:17–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maţepiuc-Stânicâ M. [Recent data on the possible consequences of influenza infections contracted during pregnancy] [Article in Romanian] Rev Ig Bacteriol Virusol Parazitol Epidemiol Pneumoftiziol Bacteriol Virusol Parazitol Epidemiol. 1976;21:11–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leetz I. [Influenza in pregnancy as a cause of perinatal mortality. 2. Case reports] [Article in German] Z Arztl Fortbild (Jena). 1973. Jul 15;67(14):713–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Menser MA, Forrest JM. Maternal infections and the developing foetus. Med J Aust 1973;1:448–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Griffith GW, Adelstein AM, Lambert PM, Weatherall JA. Influenza and infant mortality. Br Med J 1972;3:553–556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Winnebago County Death Records. 1916–1922;Vol. 22–34. Winnebago County Courthouse; Oshkosh, WI.

- 44.Wood HC, La Wall CH, Youngken HW, Anderson JF, Griffith I. The Dispensatory of the United States of America. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Company, Washington Square Press; 1926.

- 45.Spanish Influenza - “Three-Day Fever” - “The Flu.” In: Corish JL, ed. Health Knowledge, A Thorough and Concise Knowledge of the Prevention, Causes, and Treatments of Disease, Simplified for Home Use. Volume II. New York, NY: Domestic Health Society, Inc.; 1921. 982–986.

- 46.Uc A, Bishop WP, Sanders KD. Camphor hepatotoxicity. South Med J 2000;93:596–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Food Drug Administration. Proposed rules: external analgesic drug products for over-the-counter human use; tentative final monograph. Federal Register: 1983;48:5852–5869. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wisconsin Register of Reports of Contagious Diseases. 1919. Record of the Wisconsin State Historical Society; Madison, WI.