Abstract

Context

Introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has significantly decreased mortality in HIV-1-infected adults and children. Although an increase in non-HIV-related mortality has been noted in adults, data in children are limited.

Objectives

To evaluate changes in causes and risk factors for death among HIV-1-infected children in Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group (PACTG) 219/219C.

Design, Setting and Participants

Multicenter, prospective cohort study designed to evaluate long-term outcomes in HIV-1-exposed and infected US children. There were 3,553 HIV-1-infected children enrolled and followed between April 1993 and December 2006 with primary cause of mortality identified in the 298 observed deaths.

Main Outcome Measures

Mortality rates per 100 child-years overall and by demographic factors; survival estimates by birth cohort; and hazard ratios (HR) for mortality by various demographic, health and antiretroviral treatment factors were determined.

Results

Among 3,553 HIV-1-infected children followed for a median of 5.3 years, 298 deaths occurred. Death rates significantly decreased between 1994 and 2000, from 7.2 to 0.8 per 100 person-years, and remained relatively stable through 2006. After adjustment for other covariates, increased risk of death was identified for those with low CD4 and AIDS-defining illness at entry. Decreased risks of mortality were identified for later birth cohorts, and for time-dependent initiation of HAART (HR 0.54, p<0.001). The most common causes of death were “End-stage AIDS” (N=48, 16%) and pneumonia (N=41, 14%). The proportion of deaths due to opportunistic infections (OIs) declined from 37% in 1994–1996 to 24% after 2000. All OI mortality declined during the study period. However, a greater decline was noted for deaths due to Mycobacterium avium complex and cryptosporidium. Deaths from “End-stage AIDS”, sepsis and renal failure increased.

Conclusions

Overall death rates declined from 1993–2000 but have since stabilized at rates about 30 times higher than for the general U.S. pediatric population. Deaths due to OIs have declined, but non-AIDS-defining infections and multi-organ failure remain major causes of mortality in HIV-1- infected children.

INTRODUCTION

In the past decade, dramatic declines in morbidity and mortality in HIV-1-infected adults and children have been observed as a consequence of increasing use of HAART.1–8 While overall death rates have declined in HIV-infected adults, the proportion of deaths attributable to non-AIDS complications have increased, including end-organ failure and treatment-related metabolic adverse events. In one review, the duration of receiving HAART and higher CD4 count at HAART initiation in adults were associated with death from non-AIDS causes.9 There are limited data regarding causes of death in HIV-1 infected children and changes in such causes over time, most from the pre- or early HAART era.10–13 With increasing use of HAART, it is important to evaluate whether the improved survival observed in children associated with use of potent antiretroviral therapies is sustained, whether there are any shifts in causes of death in children as observed in adults, and what factors are associated with risk for morbidity and mortality.

METHODS

Subjects and Study Design

PACTG 219/219C was a prospective, multicenter cohort study designed to assess the long-term consequences of HIV-1 infection and its treatment in infected infants, children and adolescents, and of in utero and neonatal exposure to antiretroviral drugs in HIV-1-exposed but uninfected infants born to women enrolled in PACTG clinical triasl to prevent mother to child HIV-1 transmission. This analysis is confined to the HIV-1-infected children enrolled in the study. The original PACTG 219 study opened to enrollment on April 2, 1993, and allowed enrollment only of children who were co-enrolled in another PACTG treatment trial or of children whose mothers participated in such a trial. The revised version, PACTG 219C, implemented on September 15, 2000, extended enrollment to any HIV-1-infected or HIV perinatally-exposed child aged 21 years, regardless of previous participation or co-enrollment into PACTG clinical trials. PACTG 219C closed to enrollment of new patients on April 25, 2006, and the study closed to follow-up on May 31, 2007. Further details on enrollment criteria for PACTG 219/219C have been documented previously.1,14 This study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each participating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from each child's parent or legal guardian, with assent obtained from older children when age-appropriate according to local IRB requirements. The study population for these analyses included 3,553 HIV-1-infected infants, children and youth who were enrolled into PACTG 219, PACTG 219C or both between 1993 and 2006, and analyses included follow-up information through December 31, 2006.

Clinical and Laboratory Data

Medical history, physical measurements, and lymphocyte subset data were collected at baseline and every 6 months for HIV-1-infected children under 24 months of age and yearly in children 24 months of age or older for PACTG 219 participants. In PACTG 219C, HIV-1-infected children were followed every 3 months. CD4 lymphocyte subset data were obtained for study participants beginning in May of 1995. HIV-1 plasma RNA data were not routinely collected until PACTG 219C (September 2000). Patients were followed until they reached their 24th birthday, died, or were lost to follow-up. HAART was defined as the concomitant use of at least 3 antiretroviral drugs from at least 2 drug classes.

Causes of Death

A Death Report was completed whenever a child died while participating in PACTG 219/219C, which included the date of death, the primary cause of death and important contributing factors. All of the Death Reports, as well as clinical, medication and laboratory data, were reviewed by the study authors and placed into 17 categories representing cause of death. “End-Stage AIDS” was a diagnosis given to children who died typically with multi-organ failure following a prolonged course of clinical deterioration without a specific identified new illness as a cause of death. The primary outcome for the current analysis was death occurring in HIV-1-infected study participants from April 1993 through December 2006.

Risk Factors for Death

Covariates assessed as risk factors for death included the following: age, CD4 percentage, change in CD4 percentage at the last study visit (prior to death or censoring for those who did not die), year of birth, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) clinical class (http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/mmwr/mmwr1994.htm and http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/mmwr/mmwr1999.htm), race/ethnicity, gender, type of caregiver (biological parent or other caregiver), and mode of acquisition (perinatal vs. non-perinatal). Race/ethnicity was self-reported and categorized as white, non-Hispanic; black, non-Hispanic; Hispanic; and other. In PACTG 219C (but not PACTG 219), adherence was assessed using questionnaires validated in prior PACTG clinical trials, in which the caregiver was queried regarding medication administration for the last 3 days prior to the study visit.15 Medications and laboratory values measured at the most recent study evaluation prior to death (range 1–12 months) were assumed to reflect the values at death. Antiretroviral medical use and diagnosis data was available from birth for perinatally-infected children and from earliest visit at study site for children who acquired infection through blood transfusion or behavioral. Laboratory measurements such as CD4 cell counts, CD4% and viral loads were only collected while children were on study, and not retrospectively.

Statistical Methods

Death rates for each calendar year were calculated per 100 person-years under a Poisson distribution, and compared across subgroups defined by baseline characteristics using Poisson regression models. Follow-up time was calculated from study entry to the minimum of death date, study discontinuation, or last clinic visit prior to December 31, 2006. Kaplan-Meier plots and associated log rank statistics were used to summarize survival distributions across birth cohorts. Age at death was evaluated for trends over calendar time using descriptive statistics (median and interquartile range for each calendar year), and by evaluating the association of age at death with calendar time via a Spearman correlation coefficient. Univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate potential risk factors for mortality, based on time from study entry to death or censoring. The effect of HAART on mortality was evaluated considering treatment status at study entry, and by considering HAART initiation as a time-dependent covariate in extended Cox models. In addition, recent health characteristics and ART treatment experience prior to death or last study visit were compared using chi-square tests for categorical outcomes and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests for continuous outcomes. The percent of deaths attributed to each cause was evaluated for trends over calendar periods using Mantel Haenszel Chi-square tests for trend. SAS version 9 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina) was used to conduct all analyses, and all p-values are two-sided.

RESULTS

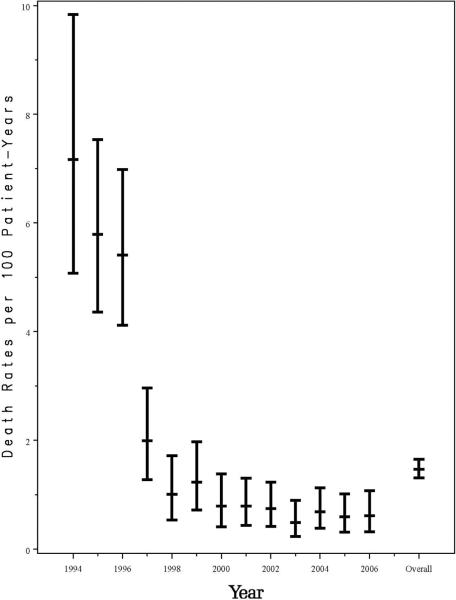

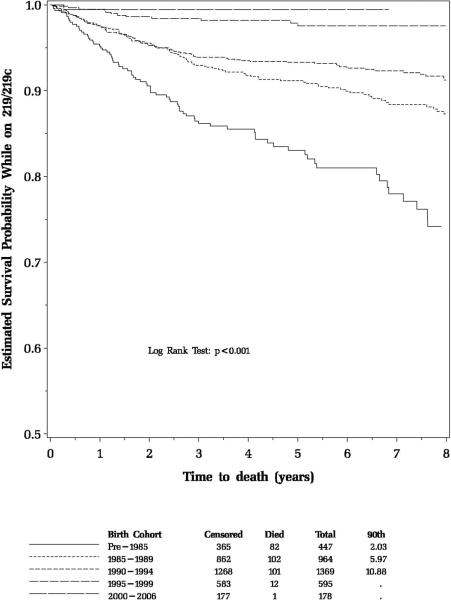

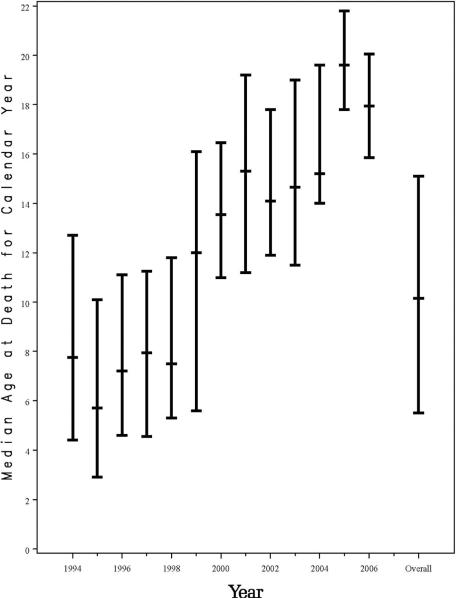

Over the 13 years of the study, 3,553 HIV-1-infected children were enrolled in PACTG 219/219C; 3,183 (90%) acquired their HIV-1 infection perinatally. Median age at enrollment was 6 years, and median follow-up was 5.3 years (20,217 person-years). Baseline demographic and health characteristics of the HIV-1-infected study participants are summarized in Table 1. There were 298 deaths among HIV-1-infected children (8% of participants), yielding an overall mortality rate of 1.47 deaths/100 person-years (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.31–1.65). A significant decline in mortality was observed from 1994 to 2000, from 7.2 deaths to 0.8 deaths per 100 person-years, concomitant with increased treatment with HAART, as previously reported1 (Figure 1). However, the mortality rates have remained relatively stable at 0.5 to 0.8 deaths/100 person-years since 2000. The estimated 6-year survival probability improved for each successive birth cohort, from pre-1985 (81%) to 1985–1989 (90%), 1990–1994 (93%), 1995–1999 (97%), and to 2000–2006 (99%, Figure 2). Following the decline in mortality rate, the age at death increased significantly from 8.9 years in 1994 to 18.2 years by 2006 (p=<0.001, Figure 3).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Health Characteristics for HIV-1 Infected PACTG 219/219C Participants Overall and By Survival Status

| Survival Status | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (N=3553) | Alive (N-3255) | Dead (N=298) | p-value | ||

| Sex | Male | 1719 (48%) | 1564 (48%) | 155 (52%) | 0.20 (a) |

| Female | 1834 (52%) | 1691 (52%) | 143 (48%) | ||

| Age at Entry | Median | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.16 (b) |

| 0–2.9 years | 951 (27%) | 870 (27%) | 81 (27%) | ||

| 3–5.9 years | 567 (16%) | 513 (16%) | 54 (18%) | ||

| 6–9.9 years | 957 (27%) | 893 (27%) | 64 (21%) | ||

| 10–14.9 years | 725 (20%) | 654 (20%) | 71 (24%) | ||

| 15 or older | 353 (10%) | 325 (10%) | 28 ( 9%) | ||

| Birth Cohort | Median | 1991 | 1991 | 1988 | <0.001 (c) |

| Pre–1985 | 447 (13%) | 365 (11%) | 82 (28%) | ||

| 1985–1989 | 964 (27%) | 862 (26%) | 102 (34%) | ||

| 1990–1994 | 1369 (39%) | 1268 (39%) | 101 (34%) | ||

| 1995–1999 | 773 (22%) | 760 (23%) | 13 ( 4%) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | White | 517 (15%) | 460 (14%) | 57 (19%) | 0.04 (b) |

| Black | 2028 (57%) | 1878 (58%) | 150 (50%) | ||

| Hispanic | 947 (27%) | 860 (26%) | 87 (29%) | ||

| Other race | 61 ( 2%) | 57 ( 2%) | 4 ( 1%) | ||

| Primary Caregiver | Biological parent(s) | 1768 (50%) | 1601 (49%) | 167 (56%) | 0.003 (b) |

| Other Relative | 780 (22%) | 706 (22%) | 74 (25%) | ||

| Other Adult | 830 (23%) | 781 (24%) | 49 (16%) | ||

| Other/unknown | 175 ( 5%) | 167 ( 5%) | 8 ( 3%) | ||

| Caregiver Education Level | Less than High School | 1340 (38%) | 1228 (38%) | 112 (38%) | 1.00 (a) |

| High School Graduate | 2209 (62%) | 2023 (62%) | 186 (62%) | ||

| Missing/Unknown | 4 ( 0%) | 4 ( 0%) | 0 ( 0%) | ||

| Route of HIV Acquisition | Perinatal | 3183 (90%) | 2920 (90%) | 263 (88%) | |

| Postnatal | 370 (10%) | 335 (10%) | 35 (12%) | ||

| CD4% at Entry | Media | 27 | 28 | 8 | <0.001 (c) |

| 0–14% | 575 (16%) | 405 (12%) | 170 (57%) | ||

| 15–24% | 725 (20%) | 682 (21%) | 43 (14%) | ||

| 25% or higher | 1935 (54%) | 1899 (58%) | 36 (12%) | ||

| Missing/unknown | 318 ( 9%) | 269 ( 8%) | 49 (16%) | ||

| HIV-1 Plasma RNA at Entry | Median | 1219 | 1026 | 64326 | <0.001 (c) |

| 0–400 copies | 750 (21%) | 747 (23%) | 3 ( 1%) | ||

| 401–5000 copies | 359 (10%) | 256 (11%) | 3 ( 1%) | ||

| 5001–50,000 copies | 399 (11%) | 378 (12%) | 21 ( 7%) | ||

| 50,000+ copies | 274 ( 8%) | 243 ( 7%) | 31 (10%) | ||

| Missing/unknown | 1771 (50%) | 1531 (47%) | 240 (81%) | ||

| CDC Clinical Class C at Entry | Not Class C | 2617 (74%) | 2462 (76%) | 155 (52%) | <0.001 (a) |

| Class C | 922 (26%) | 779 (24%) | 143 (48%) | ||

| Missing/unknown | 14 ( 0%) | 14 ( 0%) | 0 ( 0%) | ||

| Antiretroviral Regimen at Entry | HAART with PI | 1276 (36%) | 1237 (38%) | 39 (13%) | <0.001 (b) |

| HAART w/out PI | 314 ( 9%) | 300 ( 9%) | 14 ( 5%) | ||

| DualNRTI | 751 (21%) | 679 (21%) | 72 (24%) | ||

| Single NRTI | 769 (22%) | 638 (20%) | 131 (44%) | ||

| Other ARV | 170 ( 5%) | 153 ( 5%) | 17 ( 6%) | ||

| Not on ARV | 273 ( 8%) | 248 ( 8%) | 25 ( 8%) | ||

Fisher's Exact Test

Pearson's Chi-Square Test

Kruskal-Wallis Test

Figure 1.

Death Rates per 100 Patient-Years for PACTG 219/219C Participants for Each Calendar Year from 1994 through 2006, with exact 95% Confidence Intervals.

Figure 2.

Estimated Survival Probability of PACTG 219/219C Participants by Successive Birth Cohorts.

Figure 3.

Median Age at Death by Year for HIV-1-Infected Participants in PACTG 219/219C in Each Calendar Year from 1994 through 2006, with Interquartile Ranges

There was no difference in crude mortality rates by gender, with mortality rates of 1.55 for males and 1.38 for females per 100 person years (p=0.31). However, in the final multivariate Cox proportional hazards model adjusting for all potential confounders, females had a marginally significant increase in risk of death as compared to males (Table 2). Similarly, while Hispanic children had a slightly higher death rate in crude comparisons (Table 1), fewer used HAART prior to entry (37% vs 48%, p<0.001) and Hispanics tended to be older at initiation of HAART than non-Hispanics (mean of 9.0 years versus 7.7 years, p=0.007), which might have been expected to increase mortality risk. Thus, after adjustment for initiation of HAART as a time-dependent indicator, the risk of death for children identified as Hispanic ethnicity was 30% lower than for non-Hispanic white and black participants (p=0.01, Table 2).

Table 2.

Full and Reduced Multivariate Cox Model for Time to Death Evaluating Baseline Characteristics and HAART Initiation

| Full Multivariate Cox Model (n=3218) | Reduced Multivariate Cox Model with Time-dependent HAART*,** (n=3222) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Female | 1.30 | (1.01–1.68) | 0.04 | 1.28 | (0.99–1.64) | 0.06 |

| Race | 0.12 | |||||

| White | 1.00 (ref) | --- | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| Black | 0.94 | (0.66–1.34) | 0.73 | --- | --- | --- |

| Hispanic | 0.68 | (0.46–1.00) | 0.05 | --- | --- | --- |

| Other race | 1.24 | (0.38–4.04) | 0.73 | --- | --- | --- |

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic | --- | --- | --- | 0.70 | (0.53–0.93) | 0.01 |

| CD4 Percent at entry | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| <15% | 11.0 | (7.56–16.3) | <0.001 | 11.98 | (8.15–17.6) | <0.001 |

| 15–25% | 2.41 | (1.52–3.80) | <0.001 | 2.46 | (1.56–3.89) | <0.001 |

| >25% | 1.00 (ref) | -- | -- | 1.00 (ref) | -- | |

| Age in years at entry | 0.84 | (0.79–0.90) | <0.001 | 0.88 | (0.84–0.93) | <0.001 |

| Birth cohort | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||||

| Pre–1985 | 1.00 (ref) | -- | -- | 1.00 (ref) | -- | |

| 1985–1989 | 0.27 | (0.17–0.42) | <0.001 | 0.31 | (0.20–0.48) | <0.001 |

| 1990–1994 | 0.15 | (0.08–0.28) | <0.001 | 0.21 | (0.12–0.37) | <0.001 |

| 1995–1999 | 0.05 | (0.02–0.13) | <0.001 | 0.09 | (0.036–0.21) | <0.001 |

| 2000–2006 | 0.02 | (0.002–0.02) | <0.001 | 0.04 | (0.005–0.34) | |

| CDC Class C at entry | 2.27 | (1.76–2.94) | <0.001 | 2.38 | (1.84–3.08) | <0.001 |

| HAART Initiation** | 0.91 | (0.61–1.37) | 0.66 | 0.54 | (0.38–0.75) | <0.001 |

| Primary Caregiver | ||||||

| Biological parent or relative | 1.00 (ref) | --- | --- | --- | ||

| Other adult | 1.66 | (0.78–3.56) | 0.19 | --- | --- | --- |

| Primary caregiver high school graduate | 1.08 | (0.82–1.40) | 0.59 | --- | --- | --- |

| Perinatally HIV-1 infected | 0.90 | (0.56–1.44) | 0.64 | --- | --- | --- |

| Small clinical site (<20 accrued in PACTG 219/219c) | 1.07 | (0.66–1.72) | 0.80 | --- | --- | --- |

Viral load not included due to lack of availability of this value at entry to PACTG 219.

Time-dependent initiation of HAART, equal to 0 for those never on HAART, equal to 1 at baseline if initiation of HAART occurred prior to entry, otherwise equal to 1 at time of HAART initiation for those who began after study entry. Reduced model includes covariates with p<0.10.

Factors associated with an increased risk for death were CD4 cell percentage at entry less than 15% or 15–25% compared to >25%, having an AIDS-defining (CDC clinical class C) diagnosis at entry, younger age at entry, and belonging to an earlier birth cohort. Covariates not found to be associated with risk of death in the multivariate models included type of caregiver, caregiver education level, size of site (defined by the number of participants at site), and mode of acquisition of infection (perinatally vs non-perinatally acquired).

As noted previously, viral load data were not routinely captured until 2000, however, multivariate Cox models applied to the subset of 1,727 subjects (49%) with viral load data at or prior to study entry generally yielded similar results to those shown in Table 2. Subjects with viral load levels above 5,000 copies/mL had greater than a 4-fold increased risk of death as compared to those with ≤400 copies/mL (HIV RNA 5,000–50,000 copies/mL: HR=4.55, 95% CI:1.27–16.3, p=0.02; HIV-1 RNA>50,000 copies/mL: HR=4.42, 95% CI 1.20–16.2, p=0.03). Among those who entered in the year 2000 or later (when viral load measurements became routinely available), those who had a viral load at entry (n=1471) were not significantly different than those without an entry viral load (n=211) with respect to sex, age, type of primary care giver, caregiver education, CD4% at entry, duration on HAART and prior CDC Class C diagnosis. However, they tended to be born in later years, and were slightly more likely to be on HAART at entry (78% vs 70%). They were similar with respect to having ever received HAART (91% vs 88%). A higher percentage of those with viral load were black (64% vs 56%) and a lower percentage were Hispanic (20% vs 27%).

In a univariate Cox proportional hazards model, children and adolescents who had received or were currently receiving treatment with HAART prior to study entry had one-third the risk of death (HR=0.33, 95% CI: 0.25–0.45, model not shown) as compared to those who had not. This protective effect of HAART at or prior to entry persisted after adjustment for age, sex, race, CD4%, and CDC class but became non-significant after adjustment for birth cohort, given the close association of availability of HAART by time period. However, in the final reduced multivariate model, taking into account initiation of HAART after study entry, the time-dependent effect of HAART initiation was associated with a halving of the risk of death even after adjustment for all above covariates including birth cohort (HR=0.54, 95% CI: 0.38–0.75, p<0.001; see Table 2, right column). Children enrolled prior to the availability of HAART (1994–1996; n=238) as compared to those enrolled after the availability of HAART (1997–2006; n=3315) were similar with respect to sex, age at entry and primary care giver education level. However, children enrolled in the pre-HAART era did have some significantly different baseline demographic characteristics compared with those enrolled in the HAART era. Differences in the two groups include race/ethnicity (higher proportion of white and Hispanic children in pre-HAART era); CD4% at entry (median of 9% in pre-HAART and 28% in HAART era); and percentage with CDC Class C diagnosis (35% in pre-HAART era and 25% in HAART era). These differences may reflect not only differences in treatment effectiveness of pre-HAART regimens but also reflect different eligibility requirements for PACTG 219/219C which initially was limited to PACTG treatment protocol participants but later became more liberal to allow enrollment of HIV-1-infected children regardless of treatment regimen or participation in a PACTG protocol.

Of the 3,553 HIV-infected children followed on PACTG 219/219C, 2,933 (83%) received HAART therapy at some time during the PACTG 219/219C study period (Table 3). However, children who died were significantly less likely to have received HAART (49% versus 86% of those remaining alive, p<0.001). Of the 152 children who died between 1994 and 1996, only 14% had received a HAART regimen, primarily nevirapine-based HAART, and only 5% had received a regimen with a protease inhibitor (PI), generally available only through clinical trials. In contrast, in children who died after 1996, 85% had received at least one HAART regimen and 82% had received at least one HAART regimen with a PI. However, the children enrolled after 1996 who died tended to have received HAART for a shorter period of time compared to those that did not die (65% of those who died had received <5 years of HAART compared to 32% of those who did not die, data not shown).

Table 3.

Antiretroviral History Prior to Death or Prior to Censoring in Those Who Did Not Die

| Survival Status |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Total (N-3553) | Alive (N-3255) | Dead (N-298) | p-value |

| Ever on HAART | ||||

| No | 620 (17%) | 468 (14%) | 152 (51%) | <0.001 (a) |

| Yes | 2933 (83%) | 2787 (86%) | 146 (49%) | |

| HAART duration (months) | ||||

| Median | 68 | 74 | 0 | <0.001 (b) |

| Never on HAART | 621 (17%) | 469 (14%) | 152 (51%) | |

| 0–2 years | 264 ( 7%) | 216 ( 7%) | 48 (16%) | |

| 2–5 years | 732 (21%) | 685 (21%) | 47 (16%) | |

| 5–8 years | 642 (18%) | 611 (19%) | 31 (10%) | |

| More than 8 years | 1294 (36%) | 1274 (39%) | 20 ( 7%) | |

| # Unique ART agents used | ||||

| Median | 6 | 6 | 3 | <0.001 (b) |

| None | 50 ( 1%) | 44 ( 1%) | 6 ( 2%) | |

| 1–3 | 774 (22%) | 617 (19%) | 157 (53%) | |

| 4–6 | 1164 (33%) | 1120 (34%) | 44 (15%) | |

| 7–9 | 977 (27%) | 936 (29%) | 41 (14%) | |

| 10 or more | 588 (17%) | 538 (17%) | 50 (17%) | |

| # Unique NRTIs used | ||||

| Median | 4 | 4 | 3 | <0.001 (b) |

| None | 50 ( 1%) | 44 ( 1%) | 6 ( 2%) | |

| 1–2 | 797 (22%) | 656 (20%) | 141 (47%) | |

| 3–4 | 1615 (45%) | 1522 (47%) | 93 (31%) | |

| 5 or more | 1091 (31%) | 1033 (32%) | 58 (19%) | |

| # Unique NNRTIs used | ||||

| Median | 1 | 1 | 0 | <0.001 (b) |

| None | 1507 (42%) | 1337 (41%) | 1790 (57%) | |

| 1 | 1668 (47%) | 1568 (48%) | 100 (34%) | |

| 2 | 370 (10%) | 342 (11%) | 28 ( 9%) | |

| 3 | 8 ( 0%) | 8 ( 0%) | 0 ( 0%) | |

| # Unique PIs used | ||||

| Median | 1 | 2 | 0 | <0.001 (b) |

| None | 815 (23%) | 645 (20%) | 170 (57%) | |

| 1–2 | 1740 (49%) | 1683 (52%) | 57 (19%) | |

| 3–4 | 752 (21%) | 707 (22%) | 45 (15%) | |

| 5 or more | 246 ( 7%) | 220 ( 7%) | 26 ( 9%) | |

Fisher's Exact Test

Kruskal-Wallis Test

Median CD4 T-lymphocyte percentages and absolute cell counts and HIV-1 RNA viral loads at last available visit (when available) were significantly different for study participants who died versus those who did not die. In particular, the median CD4% was 3% versus 29%, respectively, and median CD4 cell count was 19 cells/mm3 as compared to 649 cells/mm3. While CD4 cell counts and CD4% were significantly different in study participants who died versus those who did not die, the change in CD4 cell count nor CD4% measured at the two latest visits prior to death or censoring was not found to be associated with risk of death using a logistic regression model [OR=1.01 (p=0.56)]. For children with viral load measured during follow-up (n=3174), median HIV-1 RNA was 111,768 copies/mL versus 1,200 copies/mL (p<0.001) for deaths versus survivors, and 68% of those who died had >50,000 copies/mL compared to only 14% of those who survived (p<0.001).

In the subset of participants who completed adherence assessments15 (i.e., those on PACTG 219C), there was no difference in adherence between those who died and those who survived: (78% versus 76% reported complete adherence during past 3 days), and no difference in adherence for any specific drug class.

Ninety-seven percent of the deaths for which a cause had been identified were directly related to the child's HIV-1 infection (Table 4). Five children developed cerebral hemorrhage, which was associated with sickle cell disease in two children and without a known etiology in the other 3 cases. There were 2 accidental deaths. The two most common causes of death were “End stage AIDS” (n=48, or 16%) and pneumonia (n=46, or 15%, acute and chronic; not including Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia). AIDS-defining opportunistic infections [Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC); cytomegalovirus (CMV); Cryptosporidium; Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP); toxoplasmosis; Cryptococcus] were responsible for 92 (31%) deaths. Of these, MAC was responsible for 43 deaths, representing 47% of all opportunistic infection-related deaths and 11% of all deaths. None of the deaths were directly attributed to adverse drug toxicities or to the Immune Reconstitution Inflammatory Syndrome (IRIS).

Table 4.

Primary Cause of Death by Calendar Period for HIV-1-Infected Children

| Calendar Period |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grouped Cause of Death | Total N=298 | 1994–1996 N=152 | 1997–2000 N=66 | 2001–2006 N=80 | Trend test p-value* |

| p=0.03 | |||||

| AIDS-Defining Infection | 92 | 55 (36.2%) | 18 (27.2%) | 19 (23.8%) | |

| Mycobacterium avium complex | 43 | 29 (19.0%) | 9 (13.6%) | 5 (6.3%) | |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii | 27 | 14 (9.2%) | 5 (7.6%) | 8 (10.0%) | |

| pneumonia (PCP) | |||||

| Cytomegalovirus | 10 | 5 (3.3%) | 2 (3.0%) | 3 (3.8%) | |

| Cryptosporidium | 5 | 4 (2.6%) | 1 (1.5%) | 0 | |

| Cryptococcus/Toxoplasmosis | 4 | 2 (1.3%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| Invasive Candidiasis | 3 | 1 (0.7%) | 1 (1.5%) | 1 (1.3%) | |

| End-Stage AIDS | 48 | 18 (11.8%) | 11 (16.7%) | 19 (23.8%) | |

| Pneumonia | 41 | 23 (15.1%) | 13 (19.7%) | 5 (6.3%) | |

| Sepsis - bacterial or fungal | 34 | 16 (10.5%) | 6 (9.1%) | 12 (15.0%) | |

| Cardiomyopathy | 20 | 11 (7.2%) | 3 (4.5%) | 6 (7.5%) | |

| Central Nervous System Disease | 19 | 12 (7.9%) | 4 (6.1%) | 3 (3.8%) | |

| Malignancy | 9 | 3 (2.0%) | 3 (4.5%) | 3 (3.8%) | |

| Renal failure | 7 | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (3.0%) | 4 (5.0%) | |

| Stroke/cerebral Hemorrhage | 5 | 1 (0.7%) | 2 (3.0%) | 2 (2.5%) | |

| Hepatitis | 4 | 2 (1.3%) | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| Accidental | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 (2.5%) | |

| Other/Unknown | 17 | 9 (5.9%) | 4 (6.1%) | 4 (5.0%) | |

= Test of trend in proportion of deaths due to each cause over calendar periods using Mantel-Haenszel Chi-Square test. For trends in Opportunistic Infection (OI)-related vs non-OI related deaths, the Mantel-Haenszel test p-value is 0.03.

The proportion of deaths caused by opportunistic infections declined from 36% in 1994–1996 to 24% in 2001–2006 (trend test p=0.04, Table 4). Most notable were the declines in deaths attributed to MAC and Cryptosporidium. The proportion of deaths due to PCP and CMV were unchanged. There was also a decline over time for pneumonia and central nervous system (CNS) disease as causes of death. However, there were increased proportions of total deaths noted for “End stage AIDS”, sepsis, and renal failure. There were 7 deaths attributed to HIV-associated renal disease. All but one occurred in children listed as black race. When all 12 categories shown in Table 4 were evaluated for trends over the three calendar periods and compared across causes, there was a significant difference in trends over the time (Mantel Haenszel p = 0.03); in particular, there was a significant decline in the proportion of deaths due to opportunistic infections versus non-opportunistic deaths (p=0.03). The above trend remained marginally significant when excluding the two accidental deaths and all deaths classified as “unknown” or “other” (p=0.07).

DISCUSSION

PACTG 219/219C was developed to provide long-term monitoring of many health and quality of life events, including mortality, in HIV-1-infected and HIV-1-exposed children. One of the greatest strengths of this study population is its large size (n=3,553) and long duration of follow-up (1993–2006). Limitations of this study include that it was initially developed to follow children who had been enrolled into PACTG treatment protocols. Subsequent versions allowed more liberal enrollment of HIV-1-infected children. In addition, the study participants must have survived until the time they enrolled into PACTG 219/219C. If the children who died prior to the time this study was open were more likely to die prior to receipt of HAART then our estimated hazard ratios would most likely be attenuated (bias towards the null); this actually strengthens our findings in the face of such selection bias. Death Reports were completed at individual sites with a potential for observer variation in defining primary and contributing causes of death.

Marked reductions in morbidity and mortality in HIV-1-infected children and adults have been observed since 1996 in the United States and Europe, temporally associated with increased use of HAART.1–13 In a prior analysis from the PACTG 219 pediatric cohort, an 87% decrease in the risk of mortality was observed in HIV-1-infected children in the three year period from 1996 to 1999 (from an annual mortality of 7.2% to 0.8%, respectively), a time period during which protease inhibitor use in the cohort increased from 7% to 73%.1 Likewise, in a cohort of HIV-1-infected children followed in the United Kingdom and Ireland, mortality decreased by 93% through mid-2006, from 8.2 deaths per 100 person-years prior to 1997 to 0.6 per 100 person-years during 2003-June 2006.5 Our analyses from PACTG 219/219C are now extended through December 2006, with 83% of children having ever received HAART, and demonstrates that the decrease in mortality previously observed in our cohort has been sustained, with a decline in death rates from 7.1 per 100 person-years in 1994 to 0.6 per 100 person-years in 2006, very similar to the European data.

In a study evaluating the survival benefits of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1-infected adults in the U.S., per-person survival associated with HAART increased from 7.8 years in 1996 to 13.3 years in 2003.7 Consistent with these data, the mean age at death in the HIV-1-infected children in our cohort primarily infected perinatally increased significantly over time, from 9 years to 18 years in 2006. Survival has significantly increased in successive birth cohorts throughout the study period. Over 90% of all deaths in the 219/219C cohort occurred in children born prior to 1995; there was only 1 death in 178 children born in 2000–2006. In contrast, in the pre-HAART era, approximately 26% of HIV-infected children died prior to age 6 years.16 A recent South African study demonstrated a 75% reduction in early mortality in children with normal immune function (CD4 ≥25%) initiating HAART prior to age 12 weeks compared to delaying HAART until the child meets clinical or immune criteria.17 Similarly in the U.S., recommendations made since 1998 to initiate HAART for all children diagnosed with HIV infection under 1 year of age, regardless of clinical, viral or immune status,18 may have accounted for the dramatic decrease in mortality in successive birth cohorts and also prevented deaths due to IRIS.19, 20

Although the decline in mortality in the PACTG 219/219C cohort has been sustained, further declines in mortality since 2000 have not been observed, but rather a plateau at low but persistent mortality rates ranging from 0.5–0.8 per 100 patient-years. This is similar to the U.K. cohort, where mortality has been stable at rate of 0.6–0.9 per 100 patient-years since 2000.5 These mortality rates, while a dramatic reduction in our cohort of HIV-1-infected children, they are still 30 times higher than similarly-aged U.S. children (0.0150 and 0.0233 per 100 White and African-American Children in 2005, respectively).21

A review of deaths in HIV-1-infected children in the United States between 1996–199922 provided similar percentages to our 219/219C cohort between 2001–2006 for deaths due to PCP (7.5% vs 10.0%), nontuberculous mycobacteria (6.0% vs 6.3%), cytomegalovirus (4.4 vs 3.8%), sepsis (16.9% vs 15.0%), and kidney disease (both 5.0%). Some decreases in proportions of deaths were noted between the two time periods for pneumonia (14.8% vs 6.3%), heart disease (11.7% vs 7.5%), and liver disease (4.1% vs 2.5%). In the 1996–1999 review, 12.5% of deaths were due to respiratory failure or wasting/cachexia, which are likely components of “End stage AIDS” reported by 23.8% in our cohort. Thus, unlike reported observations in HIV-1-infected adults, the causes of death among HIV-infected children in the HAART era have not had major changes since the late 1990's; the percent of deaths attributable to each of these causes has evolved throughout these time periods. Nevertheless, infections of all types continue to predominate as cause of death in children in the HAART era, accounting for 45% of deaths for 2001–2006.

In our cohort, the proportion of deaths due to AIDS-defining opportunistic infections have declined over time (36% in 1994–1996 to 24% in 2001–2006), but the proportion of deaths due to non-AIDS-defining infections (e.g. pneumonia and bacterial or fungal sepsis) remained relatively stable (26% of deaths in 1994–1996 and 21% in 2001–2006) as did deaths due to PCP (8–10%). Of the 8 children who died as a result of presumptive or confirmed PCP in 2001–2006, seven had been prescribed PCP prophylaxis at the last study visit prior to death. Adherence to PCP prophylaxis was not assessed; thus whether these occurrences were due to non-adherence to the prescribed prophylaxis medications, failure of prophylaxis or misdiagnosis cannot be ascertained.

There was a decline in deaths due to central nervous system disease between the pre-HAART to HAART eras (8% in 1994–1996 to 4% in 2001–2006) while the proportion of deaths due to malignancy and cardiomyopathy remained relatively stable over the calendar periods (2–5% and 4–8% respectively). Deaths due to stroke/cerebral hemorrhage or hepatitis were low in all years but together accounted for 5% of deaths for 2001–2006. In contrast, the proportion of deaths attributed to renal failure increased from <1% in1994–1996 to 5% in 2001–2006. The prevalence of childhood HIV-associated nephropathy is unknown, as renal biopsies are not routinely performed in children with proteinuria. In the pre-HAART era, a 10–15% prevalence of childhood renal disease was reported in populations consisting largely of African American HIV-1-infected children.23, 24 Although some data suggest antiretroviral therapy may be beneficial in patients with HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN)25, 26, the observed increase in renal disease in children, and particularly in African-American HIV-1-infected children in the HAART era needs further evaluation. Given the increased risk of HIVAN ini African Americans, it appears that there may be a more complex interplay of host genetics and renal toxicity resulting from HIV-1-infection and the medications used to treat HIV-1 and its complications. Close monitoring of renal function is important for all HIV-1-infected children, but is essential for protecting the health of HIV-1-infected African American children.

The proportion of children dying from “End stage AIDS” increased from 12% in 1994–1996 to 24% in 2001–2006. The diagnosis of “End stage AIDS” represents slow but progressive multiorgan failure felt due to HIV-1-infection but with variable progression and pathophysiology in the individual child. These patients' deaths are the culmination of cyclic, progressive malnutrition due to HIV-infection, impaired nutritional intake, increased metabolic rates, immune dysfunction, chronic infectious and non-infectious inflammatory complications. Children who died from “End stage AIDS” were older than children dying of other causes and represent children who more likely initiated ART with mono- and dual-antiretroviral drug regimens, now considered suboptimal due to greater risk for generating multi-drug resistant virus unresponsive to the limited drugs approved for children.

As might be predicted, the children who died had more advanced disease at entry into the study than those who did not die, as indicated by low CD4+ cell count and advanced CDC clinical stage disease both at entry and at last available visit. Children who died were almost four times more likely to have never received HAART than those who did not die (51% vs 14%, respectively), which is likely related to the fact that nearly 60% of deaths occurred prior to 1997. Previous analyses in this cohort have shown that single and dual NRTI regimens were used most frequently through 1997.27 From 1998, HAART regimens including a protease inhibitor became commonly used.28 Children who died and had received HAART received it for a shorter time than those who did not die: 33% vs 8%, respectively, received it for less than 2 years.

The only demographic classification that was associated with an effect on mortality rates was a somewhat lower mortality in Hispanic children, despite Hispanic children having less HAART experience at study entry and starting HAART at older ages than non-Hispanic children. This difference in mortality in Hispanic children deserves additional investigation to see if it persists over time in our patients, or is noted in other study populations. During this follow up period, there was no difference in the time to death between those children who were infected perinatally when compared to those whose infection was not acquired perinatally.

The profound decrease in AIDS-defining opportunistic infections but increase in non-AIDS-defining infections as cause of death might suggest that HAART can prevent the immune compromise associated with AIDS but may not be capable of either reversing or preventing some other components of the HIV-1-associated immune dysregulation. Another explanation for the plateau in mortality could be due to continued deaths among children whose therapy has lost effectiveness as a result of development of resistance to available antiretroviral medications or they have become unable to maintain the high level of medication adherence necessary for effective HAART therapy for such a prolonged period of time.

With currently available antiretroviral and opportunistic infection therapies, the majority of HIV-1-infected children can now be expected to reach adulthood. A gain in longevity of life should be linked to an improved quality of life for our long term surviving cohorts of children and adolescents. Challenges for our patients include minimizing toxicity of antiretroviral treatment, continued development of antiretroviral agents with novel mechanisms of action to circumvent resistance and more convenient dosing to enhance adherence, psychosocial support through adolescence into young adulthood, transition to adult care and when appropriate provision of complimentary palliative and end of life care.29

REFERENCES

- 1.Gortmaker SL, Hughes M, Cervic J, Brady M, Johnson GM, Seage GR, 3rd, Song LY, Dankner WM, Oleske JM. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 219 Team. Effect of combination therapy including protease inhibitors on mortality among children and adolescents infected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1522–1528. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel K, Hernán M, Williams P, Seeger J, McIntosh K, Van Dyke R. Seage III GR for the PACTG219/219C Study Team. Long-term Effectiveness of Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) on the Survival of Children and Adolescents infected with HIV-1. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2008;46:507–515. doi: 10.1086/526524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrams EF, Weedon J, Bertolli J, Bornschlegel K, Cervia J, Mendez H, Lambert G, Singh T, Thomas P. New York City Pediatric Surveillance of Disease Consortium, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Aging cohort of perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected children in New York City. New York City Pediatric Surveillance of Disease Consortium. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20:511–517. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200105000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.deMartino M, Tovo PA, Balducci M, Galli L, Gabiano C, Rezza G, Pezzoti P. Reduction in mortality with availability of antiretroviral therapy for children with perinatal HIV-1 infection. Italian Register for HIV Infection in Children and the Italian National AIDS Registry. JAMA. 2000;284:190–197. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.2.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Judd A, Doerholt K, Tookey PA, et al. Moribidy, mortality and response to treatment in children in the United Kingdom and Ireland with perinatally-acquired HIV infection during 1996–2006: planning for teenage and adult care. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:918–924. doi: 10.1086/521167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McConnell MS, Byers RH, Frederick T, et al. Trends in antiretroviral therapy use and survival rates in HIV-infected children and adolescents in the United States, 1989–2001. JAIDS. 2005;38:488–494. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000134744.72079.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Losina E, et al. The survival benefits of AIDS treatment in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2006;194:11–19. doi: 10.1086/505147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mocroft A, Ledergerber B, Katlama C, et al. Decline in the AIDS and death rates in the EuroSIDA study: an observational study. Lancet. 2003;362:22–29. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)13802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Palella FJ, Jr, Baker RK, Moorman AC, Chmiel JS, Wood KC, Brooks JT, Holmberg SD, HIV Outpatient Study Investigators Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johann-Liang R, Cervia JS, Noel GJ. Characteristics of human immunodeficiency virus-infected children at the time of death: an experience in the 1990s. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1997;16:1145–1150. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199712000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Langston C, Cooper ER, Goldfarb J, et al. Human immunodeficiency virus related mortality in infants and children: data from the Pediatric Pulmonary and Cardiovascular Complications of Vertically Transmitted HIV (P2C2) study. Pediatrics. 2001;107:328–338. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.2.328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiappini E, Galli L, Tovo P-A, et al. Changing patterns of clinical events in perinatally HIV-1-infected children during the era of HAART. AIDS. 2007;21:1607–1615. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32823ecf5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doerholt K, Duong T, Tookey P, et al. Outcomes for human immunodeficiency virus-1-infected infants in the United Kingdom and Republic of Ireland in the era of effective antiretroviral therapy. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2006;25:420–426. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000214994.44346.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gona P, VanDyke RB, Williams PL, Dankner WM, Chernoff MC, Nachman SA, Seage GR. Incidence of opportunistic and other infections in HIV-infected children in the HAART Era. JAMA. 2006;296:292–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.3.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.VanDyke RB, Lee S, Johnson GM, Wiznia A, Mohan K, Stanley K, Morse EV, Krogstad PA, Nachman S, Pediatrics AIDS Clinical Trials Group Adherence Subcommittee Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group 377 Study Team Reported adherence as a determinant of response to highly active antiretroviral therapy in children who have human immunodeficiency virus infection. Pediatrics. 2002;109:e61–67. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Blanche S, Newell M-L, Mayaux M-J, et al. Morbidity and mortality in European children vertically infected by HIV-1. JAIDS. 1997;14:442–450. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199704150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Violari A, Cotton MF, Gibb DM, et al. Early antiretroviral therapy and mortality among HIV-infected infants. N Eng J Med. 359:2233–2244. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800971. 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in pediatric HIV infection. MMWR. 1998;47(RR4):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Oleske JM. Treating Children with HIV Infection: What We Can Do, We Should Do. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:605–606. doi: 10.1086/510495. 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oleske JM. When should we treat children with HIV? J Pediatr (Rio J) 2006;82:243–245. doi: 10.2223/JPED.1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.America's Children in Brief: Key National Indicators of Well-Being: 2008. Available at: http://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren/

- 22.Selik RM, Lindegren ML. Changes in deaths reported with human immunodeficiency virus infection among United States children less than thirteen years old, 1987 through 1999. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:635–641. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000073241.01043.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray PE, Xu L, Rakusan T, Liu XH. A 20-year history of childhood HIV-associated nephropathy. Pediatr Nephrol. 2004;19:1075–1092. doi: 10.1007/s00467-004-1558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Strauss J, Abitol C, Zilleruelo G, et al. Renal disease in children with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:625–630. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198909073211001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ifudu O, Rao TK, Tan CC, Fleischman H, Chirgwin K, Friedman EA. Zidovudine is beneficial in human immunodeficiency virus associated nephropathy. Am J Nephrol. 1995;15:217–221. doi: 10.1159/000168835. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Viani RM, Danker WM, Muelenaer PA, Spector SA. Resolution of HIV-associated nephropathy nephrotic syndrome with highly active antiretroviral therapy delivered by gastrostomy tube. Pediatrics. 1999;104:1394–1396. doi: 10.1542/peds.104.6.1394. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delaugerre C, Warszawski J, Chaix ML, Veber F, Macassa E, Buseyne F, Rouzioux C, Blanche S. Prevalence and risk factors associated with antiretroviral resistance in HIV-1-infected children. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1261–1269. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brogly S, Williams P, Seage GR, et al. Antiretroviral treatment in pediatric HIV infection in the United States: from clinical trials to practice. JAMA. 2005;293:2213–2220. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.18.2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lyon ME, Williams P, Woods ER, et al. Do-Not-Resuscitate orders and/o hospice care, psychological health and quality of life among children/adolescents with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:459–469. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]