Abstract

Background

Rural regions of industrialized nations are experiencing a crisis in health care access, reflecting a high disease burden and a low physician supply. The maldistribution of physicians stems partly from the low rate of entry into medical school of applicants from rural backgrounds.

Methods

We analyzed applicants to the University of Toronto medical school in 2005 (n = 2052) to test for possible institutional bias against rural applicants and possible applicant bias against the institution. The designation of rurality was assigned using the Statistics Canada classification of residential postal codes to detect residence in communities with a population of fewer than 10,000 people.

Results

Consistent with past reports, rural applicants were under-represented (n = 93, 4.5% of applicants relative to 20% of baseline population). Rural applicants, on average, were equally competitive with urban applicants as measured by grades, test scores, and interviews. Rural applicants were just as likely as urban applicants to be offered admission (17% vs 14%, p = 0.43), indicating no large bias from the institution. Rural applicants, however, were more than twice as likely to decline the admission offer (69% vs 24%, p < 0.001), indicating a large bias against the institution. This discrepancy was not explained by financial disparity and was not confined to those applicants most likely to receive invitations to other schools.

Conclusions

Programs to increase physician supply in rural areas need to address students' concealed preferences that are established before enrolment. Medical schools, in particular, need to encourage more rural students to apply and to persuade those offered admission to accept.

Introduction

A few years ago, the executive director of the Office of Rural Health stated: "if there is a two-tiered medicine in Canada, it's not rich and poor, it's urban vs. rural."1 Indeed, a perennial problem in health care for industrialized nations is a maldistribution of physicians that, in turn, contributes to long travel distances to health care services, limited access to care, and delayed follow-up. No physician, for example, practises north of latitude 70º in North America despite a population of 3,300.2 Overall, about 20% of the Canadian population is rural but only 9% of the country's physicians practise in rural areas.2 A shortfall in rural physicians is evident in other countries throughout the world.3-5 Physicians located in rural areas, moreover, are often responsible for multiple duties, carry large patient rosters, and have limited back-up.6

Improving the geographic distribution of physicians requires the recruitment of more clinicians to practise in rural communities. Past research indicates that certain characteristics distinguish rural physicians as a group. Most notably, rural physicians are up to 4–5 times more likely than their urban counterparts to come from rural backgrounds (e.g., raised and schooled in a rural community).7-15 In addition, rural physicians are 2–3 times more likely to have had rural undergraduate training and 2–3 times more likely to have rural postgraduate training.9, 13 All three characteristics are true of most rural physicians. Despite these recognizable distinctions, rural students are greatly under-represented in Canadian medical schools (11.0% overall), and there are similar shortfalls in other industrialized countries.10, 14

Two reasons may explain a lack of rural students in medical schools; namely, they don't apply, or they don't get accepted. Individuals may choose not to apply because of the cost, a lack of motivation, or distance from home.7 Alternatively, individuals may not be accepted because of a lack of credentials or a systematic admission bias. Congruent with such concerns, some recommendations now suggest increasing the enrolment of rural students in medical school by reducing financial costs, adding more rural physicians to admissions committees, applying a rural adjustment factor to academic standards, and setting quotas for rural enrolment.7 All of these policies target the institution rather than the applicant. In this study we focused on one of North America's largest medical schools, the University of Toronto's Faculty of Medicine, which trains a low proportion of rural students. We asked: "Are admissions at the University of Toronto's medical school biased against rural applicants?"

Methods

We obtained data for all students who applied to the University of Toronto's Faculty of Medicine in 2004–2005 from the office of the Associate Dean of Admissions (data from earlier years were not available for analysis). Data were grouped according to those applicants who applied but were declined an interview (rejected), those who applied and were interviewed but not offered admission (rejected), those who were offered admission but did not accept (declined), and those who were offered admission and accepted (accepted). Approval for this study was obtained from the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Research Ethics Board, and analyses were conducted using confidentiality safeguards at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences in Ontario.

The information collected for each applicant included age, gender, last degree obtained, last university attended, grade point average (GPA), Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scores (including physical sciences, biological sciences, verbal reasoning, and writing sample), overall academic score (based on review of GPA, MCAT and other criteria), non-academic score (based on review of experiences, reference letters, and personal statement), file score (sum of academic and non-academic score), interview score, total score (weighted sum of file and interview scores), and overall rank. These are the decisive data that determine all offers of admission and are restricted from public view.

Designations of rurality and socioeconomic status were based on the permanent home postal code of the applicant's family. In cases where the applicant had listed no permanent postal code, we used the applicant's home postal code. Applicants who had provided neither a permanent nor a home postal code were excluded from the analysis. Rural status was defined as a local population of fewer than 10,000 people, using Statistics Canada data. Classification of rurality was conducted using computerized linkages in a manner blind to all other characteristics of the applicant, including the final decision with respect to admission. The same technique was also used to estimate socioeconomic status quintiles by neighborhood household income.

Statistical analysis was conducted using StatView 5.0 (SAS Institute, Inc.) using two-tailed tests throughout. Comparative descriptive statistics were based on means or percentages, as appropriate, to compare urban and rural students. Univariate differences were analyzed using an unpaired t test or chi-square test as appropriate. Multivariate analyses were conducted using logistic regression to determine if rural students were less likely to be offered admission, using background (rural vs urban) as the main predictor variable and decision of the institution (offered vs rejected) as the main outcome variable. The same analyses then tested the decision of the individual (accepted vs declined) as the main outcome variable.

Results

During the study, a total of 2106 individuals applied for admission to the University of Toronto medical school. Overall, 54 applicants were excluded from analysis because they provided unusable postal codes, most commonly because they resided outside of Canada (these included 52 rejected and 2 accepted applicants). This yielded a total of 2052 applicants for analysis with 1991 unique postal codes. After applying the postal code classification algorithm, we obtained 93 rural students and 1959 urban students. Rural applicants were greatly under-represented in the applicant pool (4.5%) in comparison with national proportions (approximately 20% rural).

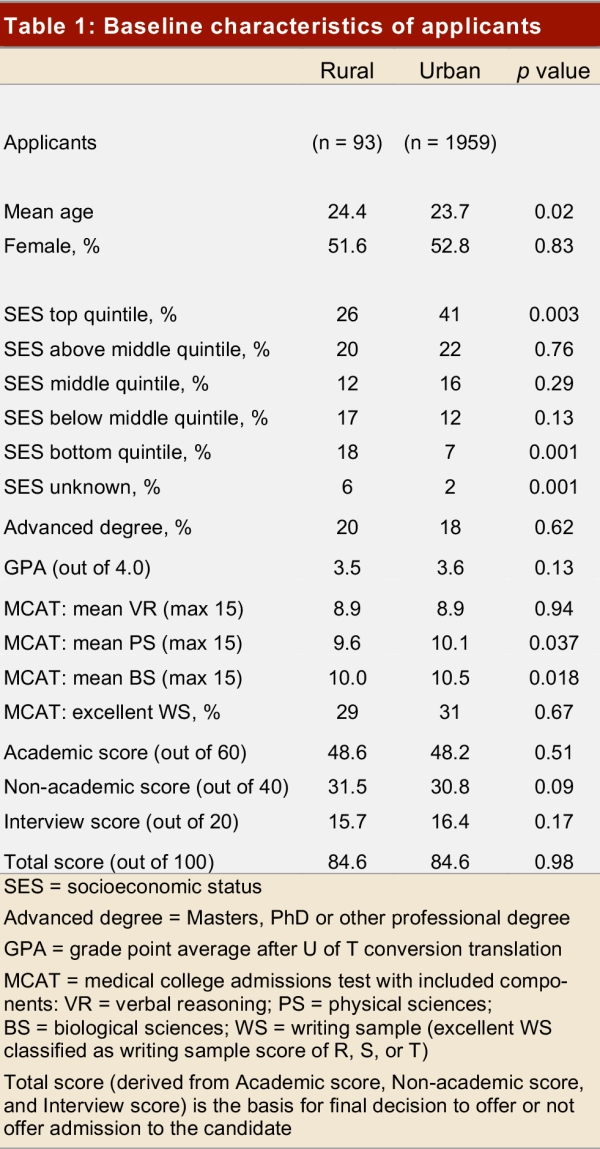

Rural and urban applicants were similar in personal background and academic merit (Table 1). Rural students had a slightly higher mean age (24.4 vs 23.7, p = 0.02) and were more often from the lowest socioeconomic quintile (18% vs 7%, p = 0.006). They were marginally more likely to have obtained an advanced degree before application (MSc, PhD, or other), but this trend was not statistically significant (p = 0.62). Rural students had slightly lower average GPA scores but a slightly higher overall academic score, perhaps suggesting that they may have taken more demanding courses. Interview scores for rural students were slightly lower, but average total scores (file score plus interview score) were identical between the two groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of applicants

Most students who applied to medical school were not granted admission. In total, 16 of the 93 rural applicants received offers of admission, whereas 279 of 1959 urban applicants received offers of admission. This amounted to a slight increase in admission offer rates in favour of rural applicants (17% vs 14%, p = 0.43). In the multivariate analysis adjusting for age, gender, GPA, and MCAT scores, rural applicants had a higher odds of an admission offer, but this was not statistically significant (adjusted odds ratio 1.63; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.87–3.04). As expected, admission offers were highly correlated with GPA and MCAT scores (p < 0.001, for both) but were not correlated with socioeconomic status (p = 0.96).

The majority of applicants who were offered admission subsequently accepted, but the difference in the proportion of rural and urban students who declined the invitation was notable. In total, 11 of 16 rural applicants declined an offer of admission, whereas 68 of 279 urban applicants declined an offer of admission. This amounted to a large absolute increase in the rate of declined admission offers by rural applicants (69% vs 24%, p < 0.001). After adjustment for age, gender, GPA, and MCAT scores, rural applicants had higher odds of declining medical school admission offers compared with urban applicants (adjusted odds ratio 7.75; 95% CI 2.37–25.38). Decisions to decline the offer were not significantly correlated with GPA, MCAT scores, or socioeconomic status (p > 0.20, for all).

The reluctance of rural applicants to accept admission offers was also examined in two important subgroups specified in advance. When we restricted the analysis to those applicants from the top two socioeconomic quintiles, and when we restricted the analysis to those applicants below the median overall rank (based on all academic and interview scores), we continued to observe higher odds ratios in declined admission offers from rural applicants compared with urban applicants: 4.93 (95% CI 1.13–21.43) and 14.86 (95% CI 1.68–131.4), respectively.

We followed up after one year on those applicants who declined offers of admission. The majority of both rural and urban students had enrolled in another medical school elsewhere in the country (73% vs 75%, p > 0.20). The rural students were distributed across six different schools with no dominant pattern of preference and no school accepting more than two individuals. None had enrolled at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine, the institution in Ontario mandated to admit and train rural physicians. A few students had left the country for medical school training (9% vs 4%, p > 0.20), and for one in five we found no evidence of subsequent medical training (18% vs 21%, p > 0.20).

Discussion

We found that only five students admitted to one of Canada's largest medical schools in 2005 were from rural backgrounds, a rate that does little to redress the shortfall in rural health care in this nation. In accord with past research from the United States,16, 17 the lack of enrolment was not explained by a lack of past training, academic accomplishments, test results, or socioeconomic status of the applicants. Nor was it explained by an overt bias on the part of the institution in favour of similarly qualified urban applicants.8, 18 Instead, we discovered that a large factor was an applicant's reluctance to accept the offer of admission. This personal choice, in turn, was not easily traced to available socioeconomic or academic characteristics.

A limitation of our research is that we cannot identify the reasons why rural applicants declined offers despite having appeared positive at the time of their direct personal interview. Ontario has other medical schools, although tuition fees are similar throughout (for 2005, $16,207 at the University of Toronto vs $14,600 at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine).19, 20 The fees outside of Ontario would be much higher by comparison (since the applicant would pay an out-of-province surcharge), and the fees in Toronto would, arguably, be much lower in some cases (due to bursary programs). Moreover, our analysis according to the applicant's socioeconomic status does not suggest that financing was the major factor in applicants' choices.

Rural applicants may decline acceptance to urban medical schools because of social rather than financial preferences. Specifically, the unfamiliar population size of a city may be a deterrent, given that rural students have grown up in small towns and possibly attended university in smaller cities as well. As noted in Australia, the structure of a city and the downtown location of a campus can also deter rural students.21 The perceived academic image of the institution and the relative lack of emphasis on rural training may not appeal to those who desire to practise as rural physicians and who want exposure to medical practice in remote regions.22 The full set of reasons is unknown because so many unmeasured factors influence an individual's decisions and people are entitled to privacy.

Our study has other limitations since the data stem from a single medical school that might not match other settings. Moreover, even a single medical school can change over time, as illustrated by the Prince George program, linked with the University of British Columbia, which promotes rural and remote training.23 However, aggregate reports from different Ontario medical schools have shown widespread difficulties in recruiting rural applicants.24 For example, the Northern Ontario School of Medicine (which preferentially selects rural applicants25) had about 26% of offers of admission declined in 2005. The situation was no different in 2006, when the Northern Ontario School of Medicine had about 28% of its admission offers declined (compared with 17% for the entire province).

Whether urban institutions should increase the number of rural students accepted to medical school remains controversial. In theory, accepting more rural students to any medical school could contribute to more potential rural physicians being trained to bridge the geographic maldistribution of health care. In addition, rural students have been shown to be more likely to enter family practice,10, 14 another area that is experiencing shortages across most industrialized countries. Yet these two workforce concerns are not the only current issues in health care; immediate clinical care is not the only priority for all medical schools; and increasing diversity requires attention to many underrepresented groups.

This study confirms the importance of increasing the pool of rural applicants in order to achieve more representation of rural students in medical school. Some rural applicants may dismiss the idea of medical school because of misinformation or a lack of awareness over financial aid; hence, information regarding these options should be publicized early. This study also suggests a need to bolster the acceptance rate of rural applicants by offering some counsel to ease the transition to the big city, emphasizing rural training in the curriculum, and highlighting rural practice incentives.26 In the interim, the data do not suggest an immediate call for revolutionary changes to the admission committee practices at large, long-established urban medical schools.

Acknowledgments

Jennifer Hensel was supported by the Determinants of Community Health Course of the University of Toronto Medical School. Donald Redelmeier was supported as a Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences. Maureen Shandling was supported as Associate Dean, Admissions and Student Financial Services of the University of Toronto Medical School. We are thankful to Deva Thiruchelvam and Radu Vestamean for data programming. We are also grateful to Dan Hackam, Leslie Nickell, Jeff Kwong, and Ian Johnson for helpful comments on specific points.

Biographies

Jennifer M. Hensel is a Medical Student at the University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.

Maureen Shandling is a Professor in the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.

Donald A. Redelmeier is a Professor in the Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ont.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Nagarajan Karatholuvu V. Rural and remote community health care in Canada: beyond the Kirby Panel Report, the Romanow Report and the federal budget of 2003. Can J Rural Med. 2004;9(4):245–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng E, Wilkins R, Pole J, Adams OB. How far to the nearest physician? Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin. 1999;1(5):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson Robin, Miller Nigel, Witter Sophie. Health-seeking behaviour and rural/urban variation in Kazakhstan. Health Econ. 2003 Jul;12(7):553–564. doi: 10.1002/hec.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richards Helen M, Farmer Jane, Selvaraj Sivasubramaniam. Sustaining the rural primary healthcare workforce: survey of healthcare professionals in the Scottish Highlands. Rural Remote Health. 2005 Mar 15;5(1):365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Onwujekwe Obinna, Uzochukwu Benjamin. Socio-economic and geographic differentials in costs and payment strategies for primary healthcare services in Southeast Nigeria. Health Policy. 2005 Mar;71(3):383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackey Paul. Stats Can under-represents rural shortage. CMAJ. 2005 Feb 1;172(3):311–2; discussion 312. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1041293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rourke James, Dewar Dale, Harris Kent, Hutten-Czapski Peter, Johnston Mary, Klassen Don, Konkin Jill, Morwood Chris, Rowntree Carol, Stobbe Karl, Young Todd. Strategies to increase the enrollment of students of rural origin in medical school: recommendations from the Society of Rural Physicians of Canada. CMAJ. 2005 Jan 4;172(1):62–65. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1040879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hutten-Czapski Peter, Pitblado Roger, Rourke James. Who gets into medical school? Comparison of students from rural and urban backgrounds. Can Fam Physician. 2005 Sep;51:1240–1241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rourke James T B, Incitti Filomena, Rourke Leslie L, Kennard MaryAnn. Relationship between practice location of Ontario family physicians and their rural background or amount of rural medical education experience. Can J Rural Med. 2005;10(4):231–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kwong Jeff C, Dhalla Irfan A, Streiner David L, Baddour Ralph E, Waddell Andrea E, Johnson Ian L. A comparison of Canadian medical students from rural and non-rural backgrounds. Can J Rural Med. 2005;10(1):36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woloschuk Wayne, Tarrant Michael. Do students from rural backgrounds engage in rural family practice more than their urban-raised peers? Med Educ. 2004 Mar;38(3):259–261. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2004.01764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curran Vernon, Rourke James. The role of medical education in the recruitment and retention of rural physicians. Med Teach. 2004 May;26(3):265–272. doi: 10.1080/0142159042000192055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laven G, Wilkinson D. Rural doctors and rural backgrounds: How strong is the evidence? A systematic review. Aust Rural Health. 2003;11:277–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2003.00534.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhalla Irfan A, Kwong Jeff C, Streiner David L, Baddour Ralph E, Waddell Andrea E, Johnson Ian L. Characteristics of first-year students in Canadian medical schools. CMAJ. 2002 Apr 16;166(8):1029–1035. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Orpin Peter, Gabriel Michelle. Recruiting undergraduates to rural practice: what the students can tell us. Rural Remote Health. 2005 Oct 4;5(4):412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Longo Daniel R, Gorman Robert J, Ge Bin. Rural medical school applicants: do their academic credentials and admission decisions differ from those of nonrural applicants? J Rural Health. 2005;21(4):346–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rabinowitz H K, Diamond J J, Markham F W, Paynter N P. Critical factors for designing programs to increase the supply and retention of rural primary care physicians. JAMA. 2001 Sep 5;286(9):1041–1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basco William T, Gilbert Gregory E, Blue Amy V. Determining the consequences for rural applicants when additional consideration is discontinued in a medical school admission process. Acad Med. 2002 Oct;77(10 Suppl):S20–S22. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200210001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.University of Toronto, Office of the Vice President and Provost Tuition Fees Schedule for Domestic Students, 2006-2007. 2006. http://www.provost.utoronto.ca/English/Content-Page-42.html.

- 20.The Undergraduate Medical Program. http://www.calendar.lakeheadu.ca/current/programs/Faculty_of_Medicine/medsprog.html.

- 21.Durkin Shane R, Bascomb Angela, Turnbull Deborah, Marley John. Rural origin medical students: how do they cope with the medical school environment? Aust J Rural Health. 2003 Apr;11(2):89–95. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1584.2003.00512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Australian Medical Workforce Advisory Committee (AMWAC) Doctors in vocational training: rural background and rural practice intentions. Aust J Rural Health. 2005;13:14–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1854.2004.00640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondro Wayne. Eleven satellite campuses enter orbit of Canadian medical education. CMAJ. 2006 Aug 29;175(5):461–462. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ontario Universities' Application Center Ontario Medical School Application Services 2006. Table 28. 2006.

- 25.Tesson G, Strasser R, Pong R W, Curran V. Advances in rural medical education in three countries: Canada, The United States and Australia. Rural Remote Health. 2005 Nov 11;5(4):397. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rabinowitz H K, Diamond J J, Markham F W, Paynter N P. Critical factors for designing programs to increase the supply and retention of rural primary care physicians. JAMA. 2001 Sep 5;286(9):1041–1048. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.9.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]