Abstract

The aim of this retrospective study was to determine the prevalence and predictors of electrical storm in 227 patients who had received implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) and had been monitored for 31.7 ± 15.6 months. Of these, 174 (77%) were men. The mean age was 55.8 ± 15.5 years (range, 20–85 yr), and the mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 0.30 ± 0.14. One hundred forty-six of the patients (64%) had underlying coronary artery disease. Cardioverter-defibrillators were implanted for secondary (80%) and primary (20%) prevention.

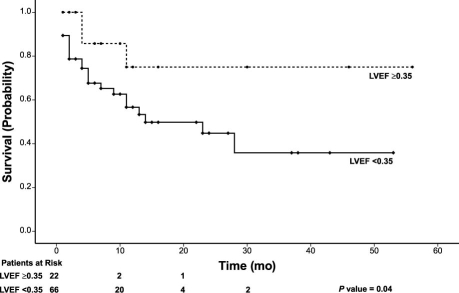

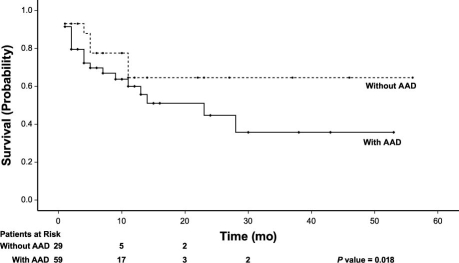

Of the 227 patients, 117 (52%) experienced events that required ICD therapy. Thirty patients (mean age, 57.26 ± 14.3 yr) had ≥3 episodes requiring ICD therapy in a 24-hour period and were considered to have electrical storm. The mean number of events was 12.75 ± 15 per patient. Arrhythmia-clustering occurred an average of 6.1 ± 6.7 months after ICD implantation. Clinical variables with the most significant association with electrical storm were low LVEF (P = 0.04; hazard ratio of 0.261, and 95% confidence interval of 0.08–0.86) and higher use of class IA antiarrhythmic drugs (P = 0.018, hazard ratio of 3.84, and 95% confidence interval of 1.47–10.05). Amiodarone treatment and use of β-blockers were not significant predictors when subjected to multivariate analysis.

We conclude that electrical storm is most likely to occur in patients with lower LVEF and that the use of Class IA antiarrhythmic drugs is a risk factor.

Key words: Antiarrhythmia agents; arrhythmias, cardiac/prevention & control; cardiac pacing, artificial; defibrillators, implantable; electric countershock; electrical storm; heart failure; tachycardia, ventricular/therapy; ventricular dysfunction, left

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) have become the main therapeutic tool for use in patients with life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias.1–3 Studies have shown that 50% to 70% of ICD patients receive appropriate device therapy within 2 years of implantation.4,5 In most patients, the total number of delivered discharges remains low. However, some patients receive multiple appropriate shocks during a short period of time consequent to recurrent or incessant ventricular tachycardia (VT) or ventricular fibrillation (VF); either of these conditions is termed an arrhythmic or electrical storm. The delivery of multiple appropriate ICD discharges for termination of recurrent ventricular tachyarrhythmias has been reported to occur in 10% to 20% of patients, depending on the duration of the observational study period.5–7 The prognostic implication of electrical storm is unclear: some early studies did not show increased mortality rates, but more recent trials have shown a highly significant association between electrical storm and subsequent fatal events.6,8

There are few data concerning electrical storm in ICD patients. Only a few studies have reported the incidence and clinical characteristics of electrical storm in these patients.5–7,9,10 Consequently, the impact of antiarrhythmic therapy on subsequent events (including electrical storm) is not well understood. The aim of this study was to determine the prevalence and predictors of electrical storm in ICD patients.

Patients and Methods

Data on 227 consecutive patients who had undergone ICD implantation at our institution from 2005 through 2006 were studied retrospectively. The type of device and the program settings were at the discretion of the implanting physician. Detection in the VF zone required that 18 of the last 24 R–R intervals had a cycle length <320 ms (>188 beats/min). The fast ventricular tachycardia (FVT) detection zone was defined as 240 to 320 ms (188–250 beats/min). Anything faster than 250 beats/min was considered to be VF and provoked a shock. The 1st therapy in the FVT zone was a single antitachycardia pacing (ATP) sequence (8 pulses, 88% of the FVT cycle length). Failed ATP was followed by a shock at 10 J above the defibrillation threshold. Programming a VT zone was also optional, for the most part; a VT zone with a cycle length of 320 to ≥360 ms (≤167–188 beats/min) was programmed.

Definition and Classification of ICD Therapy

Appropriate ICD therapy was defined as ATP or discharge therapy (shock) for VT or VF. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy was classified as appropriate or inappropriate. Therapies were defined as appropriate when delivered for VT or VF and as inappropriate when delivered for other arrhythmias, such as atrial fibrillation, sinus tachycardia, and supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), or for an artifact. Only appropriate shocks were included for analysis in the study. An electrophysiologist in the device clinic analyzed all ICD electrograms at the time of the initial electrical storm. Another electrophysiologist independently interpreted the electrograms at the time of data analysis for this study.

Definition of Electrical Storm

An electrical storm was defined as 3 or more occurrences of VT or VF that resulted in device intervention (ATP, shock delivery, or both) within a 24-hour period. For each episode of arrhythmia, the appropriateness of ICD therapy was verified by device interrogation as described.

Follow-Up

The patients were monitored at regular 3-to 6-month intervals at our arrhythmia clinic. The starting point of the follow-up period was the time of implantation of an ICD, and the endpoint was the last patient visit or the last recorded appropriate discharge. Any symptoms of syncope, arrhythmia recurrence, or ICD discharge were evaluated. Evaluation consisted of full interrogation, and recovery of the episode. The mean follow-up period was 31.7 ± 15.6 months.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SD. Univariate analysis was performed using the unpaired Student t test for continuous variables and the c2 test for categorical variables. A univariate Cox proportional hazards model was used to evaluate the significance of baseline variables. A multivariate Cox model was used to adjust for important prognostic variables and baseline differences. P <0.05 was considered significant. Analyses were performed using SPSS 15 (SPSS Inc.; Chicago, Ill) statistical software.

Results

Characteristics of the Patients

Two hundred twenty-seven patients who had undergone ICD implantation at our institution from 2005 through 2006 were included in this study. Of these, 174 (77%) were men. The mean age was 55.8 ± 15.5 years (range, 20–85 yr), and the mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was 0.30 ± 0.14. Most patients had underlying coronary artery disease (n = 146, 64%), 39 (17%) patients had idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy, 19 (8%) had hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, 13 (6%) had other heart disease, and 10 (4%) had no underlying heart disease. A dual-chamber transvenous ICD system was used in 125 (55%) patients and a single-lead device in 102 (45%).

Cardioverter-defibrillators were implanted for secondary (80%) and primary (20%) prevention.

Electrical Storm

Of the 227 patients, 117 (52%) had events that required ICD therapy. Thirty patients (13%) (mean age, 57.26 ± 14.3 yr) had ≥3 episodes that required ICD therapy in a 24-hour period and were considered to have electrical storm. The mean number of events was 12.75 ± 15 per patient. Of these 30 patients, 22 received at least 1 shock as part of their therapy for a storm event, and 13 patients received just ATP as their electrical storm therapy. This arrhythmia-clustering occurred at an average of 6.1 ± 6.7 months after ICD implantation. The mean LVEF was 0.26 ± 0.11. The indication for ICD implantation was secondary prevention in 28 of the 30 patients (93%) and primary prevention in 2 (7%). The clinical characteristics of patients with electrical storm, compared with patients without electrical storm, are set forth in Table I.

TABLE I. Baseline Characteristics of Patients with and without Electrical Storm

Analysis of ICD-stored electrograms demonstrated that clinical storm consisted of the occurrence of episodes of sustained monomorphic VT in 19 of the 30 patients (63%), fast VT in 1 (3%), VF in 1 (3%), and repeated episodes of sustained monomorphic VT and VF in 9 (30%). All patients had experienced prior episodes of ventricular tachyarrhythmias terminated by their ICD before developing electrical storm. There was no significant difference between patients who received an ICD for secondary prevention and those who received an ICD for primary prevention (P = 0.055).

Time-dependent predictors of electrical storm were determined by multivariate stepwise regression analysis with the Cox proportional hazards model. The variables with the most significant association with electrical storm were low LVEF and higher use of class IA antiarrhythmic drugs (P = 0.04; hazard ratio, 0.261; and 95% confidence interval, 0.08–0.86; and P = 0.018; hazard ratio, 3.84; and 95% confidence interval, 1.47–10.05, respectively) (Figs. 1 and 2). Amiodarone use and β-blocker use were not significant predictors when subjected to multivariate analysis.

Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier curve depicting the time to 1st electrical storm in association with left ventricular ejection fraction (<0.35 or ≥0.35), in patients at risk of electrical storm.

LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction

Fig. 2. Kaplan-Meier curve depicting the time to 1st electrical storm in association with use or nonuse of Class IA antiarrhythmic drugs, in patients at risk of electrical storm.

AAD = antiarrhythmic drugs

Discussion

Electrical storm, which has been shown to be an independent predictor of death, might indicate a more severely diseased myocardium.6,7

In our study, 30 of 227 patients (13%) experienced an episode of electrical storm during follow-up. Our results are similar to those of other reports, which suggest the occurrence of electrical storm among 10% to 20% of ICD recipients. Sustained monomorphic VT was responsible for electrical storm in a sizable but not statistically significant proportion of our patients. We did observe that low LVEF was associated with an increased risk of electrical storm. Furthermore, we found that patients treated with Class IA antiarrhythmic drugs were more likely to have electrical storm.

Credner and colleagues6 have indicated that most electrical storm episodes occur late after ICD implantation. Our data are in accordance with their results. These findings clearly indicate that electrical storm in recipients of ICDs indicates heightened electrical instability and a deterioration of the underlying arrhythmia substrate that can occur at any time in individuals who have histories of life-threatening arrhythmia.

In the AVID trial,7 the incidence of electrical storm in patients who received defibrillators for primary prevention was considerably lower than that in patients who received an ICD for secondary prevention. In another study,11 patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy and low LVEF who received ICDs for primary prophylaxis had a relatively low incidence of electrical storm. Verma and colleagues12 examined the prevalence or predictors of the causative arrhythmia for electrical storm and found that the ICD indication, the presence of coronary artery disease, and amiodarone therapy were predictors of the causative arrhythmias in electrical storm. They showed that the mortality rate was higher in patients with electrical storm than in a control group of ICD patients without electrical storm.

Our finding is dissimilar to the findings of these earlier studies. Electrical storm was observed in our ICD patients regardless of the type of the underlying heart disease. Although we found that patients who received ICD implants for primary indication had a relatively low incidence of electrical storm (Table I), ICD indication did not predict the occurrence of electrical storm. This discrepancy is likely caused by the breadth of our spectrum of patients. The definition of storm itself has varied greatly within the medical literature.5,7,11,13

Other trials (case control and prospective) have suggested differences in the baseline characteristics of patients who have electrical storm.5,9 The patients in MADIT-II11 who experienced electrical storm were similar to one another in clinical characteristics at randomization, with the exception of blood urea nitrogen levels >25 mg/dL. In our study, we found no differences in the clinical and electrocardiographic characteristics of patients who had experienced electrical storm, compared with those who had not.

On the basis of these findings, we would advise that the proarrhythmic effects of Class IA antiarrhythmic drugs after implantation of an ICD be considered. Novel ablation techniques now are available for substrate modification and prevention of VT and VF.14,15 As ablation technology advances, it may become feasible to target specific Purkinje fiber potentials or potential isthmuses in the scar border zone, in order to prevent further episodes of ventricular arrhythmia. Additional studies are needed to help evaluate therapeutic options for the prevention of electrical storm.

Conclusion

This study indicates that the prediction of electrical storm in ICD recipients on the basis of clinical characteristics is difficult. The low event rate and the retrospective nature of our study may limit the identification of variables that contribute to electrical storm, but we did find that electrical storm is most likely to occur in the subset of patients who have lower LVEFs. The adverse proarrhythmic effect of Class IA antiarrhythmic agents is also a risk factor.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Homan Bakhshandeh for his assistance with the statistics.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Zahra Emkanjoo, MD, Department of Pacemaker & Electrophysiology, Rajaie Cardiovascular Research & Medical Center, Tehran 1996911151, Iran

E-mail: emkanjoo@rhc.ac.ir

References

- 1.Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, Klein H, Wilber DJ, Cannom DS, et al. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2002;346(12):877–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Buxton AE, Lee KL, Fisher JD, Josephson ME, Prystowsky EN, Hafley G. A randomized study of the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease. Multicenter Unsustained Tachycardia Trial Investigators [published erratum appears in N Engl J Med 2000;342(17):1300]. N Engl J Med 1999;341(25):1882–90. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. The Antiarrhythmics versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators. N Engl J Med 1997;337 (22):1576–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Zipes DP, Roberts D. Results of the international study of the implantable pacemaker cardioverter-defibrillator. A comparison of epicardial and endocardial lead systems. The Pacemaker-Cardioverter-Defibrillator Investigators. Circulation 1995;92(1):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Villacastin J, Almendral J, Arenal A, Albertos J, Ormaetxe J, Peinado R, et al. Incidence and clinical significance of multiple consecutive, appropriate, high-energy discharges in patients with implanted cardioverter-defibrillators. Circulation 1996;93(4):753–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Credner SC, Klingenheben T, Mauss O, Sticherling C, Hohnloser SH. Electrical storm in patients with transvenous implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: incidence, management and prognostic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;32(7): 1909–15. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Exner DV, Pinski SL, Wyse DG, Renfroe EG, Follmann D, Gold M, et al. Electrical storm presages nonsudden death: the antiarrhythmics versus implantable defibrillators (AVID) trial. Circulation 2001;103(16):2066–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Greene M, Newman D, Geist M, Paquette M, Heng D, Dorian P. Is electrical storm in ICD patients the sign of a dying heart? Outcome of patients with clusters of ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Europace 2000;2(3):263–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Gatzoulis KA, Andrikopoulos GK, Apostolopoulos T, Sotiropoulos E, Zervopoulos G, Antoniou J, et al. Electrical storm is an independent predictor of adverse long-term outcome in the era of implantable defibrillator therapy. Europace 2005; 7(2):184–92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Endoh Y, Ohnishi S, Kasanuki H. Clinical significance of consecutive shocks in patients with left ventricular dysfunction treated with implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1999;22(1 Pt 2):187–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Sesselberg HW, Moss AJ, McNitt S, Zareba W, Daubert JP, Andrews ML, et al. Ventricular arrhythmia storms in postinfarction patients with implantable defibrillators for primary prevention indications: a MADIT-II substudy. Heart Rhythm 2007;4(11):1395–402. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Verma A, Kilicaslan F, Marrouche NF, Minor S, Khan M, Wazni O, et al. Prevalence, predictors, and mortality significance of the causative arrhythmia in patients with electrical storm. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2004;15(11):1265–70. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Nademanee K, Taylor R, Bailey WE, Rieders DE, Kosar EM. Treating electrical storm: sympathetic blockade versus advanced cardiac life support-guided therapy. Circulation 2000; 102(7):742–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Marrouche NF, Verma A, Wazni O, Schweikert R, Martin DO, Saliba W, et al. Mode of initiation and ablation of ventricular fibrillation storms in patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;43(9):1715–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Marchlinski FE, Callans DJ, Gottlieb CD, Zado E. Linear ablation lesions for control of unmappable ventricular tachycardia in patients with ischemic and nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2000;101(11):1288–96. [DOI] [PubMed]