Abstract

Isolated right superior vena cava drainage into the left atrium is an extremely rare cardiac anomaly, especially in the absence of other cardiac abnormalities. Only 28 of 5,127 reported consecutive congenital cardiac cases involved superior vena cava drainage into the left atrium, and all were associated with other cardiac anomalies. Of 19 reported cases of right superior vena cava drainage into the left atrium, most patients have been children who were experiencing mild hypoxemia and cyanosis. Herein, we describe the case of a 34-year-old woman who presented with asymptomatic hypoxemia in the peripartum period. She was diagnosed to have isolated drainage of the right superior vena cava into the left atrium. To the best of our knowledge, this is the 1st reported instance of such diagnosis by use of noninvasive imaging only, without cardiac catheterization. We also review the medical literature that pertains to our patient's anomaly.

Key words: Anoxia/etiology; blood circulation; heart atria/abnormalities; heart defects, congenital/complications/diagnosis/pathology; magnetic resonance imaging; oxygen/blood; peripartum period; technetium/diagnostic use; vena cava, superior/abnormalities/radiography

Isolated right superior vena cava (SVC) drainage into the left atrium (LA) is an extremely rare cardiac anomaly, particularly in the absence of other cardiac abnormalities. In 1975, de Leval and colleagues1 reported that only 28 of 5,127 consecutive congenital cardiac patients had SVC drainage into the LA, and all 28 instances were associated with other cardiac anomalies. There have been 19 reported cases of right SVC drainage into the LA, mostly in children who had mild hypoxemia and cyanosis. Here, we describe the case of a woman whose asymptomatic hypoxemia in the peripartum period was associated with isolated drainage of the right SVC into the LA. To the best of our knowledge, this is the 1st reported case in which solely noninvasive imaging was used to establish the diagnosis, without the use of cardiac catheterization. We also review the relevant medical literature.

Case Report

In October 2007, a 34-year-old woman came to our hospital in order to give birth to her 3rd child. Her medical history was significant only for episodic headaches since childhood; her 2 previous vaginal deliveries had been uneventful. Her blood pressure was 160/90 mmHg, and her oxygen saturation was 87% on room air. A physical examination revealed nothing unusual. Laboratory values included a hemoglobin level of 15 g/dL.

Spontaneous rupture of membranes and evidence of fetal distress developed, and an urgent cesarean section was performed. Despite intubation before the procedure, the patient became hypoxic, with an oxygen saturation that was measured at 78% in the operating room. The baby was successfully delivered by cesarean section, after which the patient was extubated; her oxygen saturation levels ranged from 85% to 94%, even upon the administration of 10 L of oxygen through a nasal cannula.

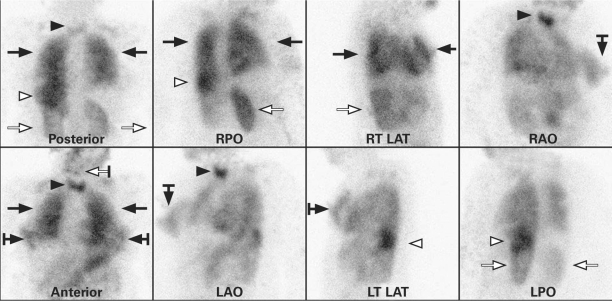

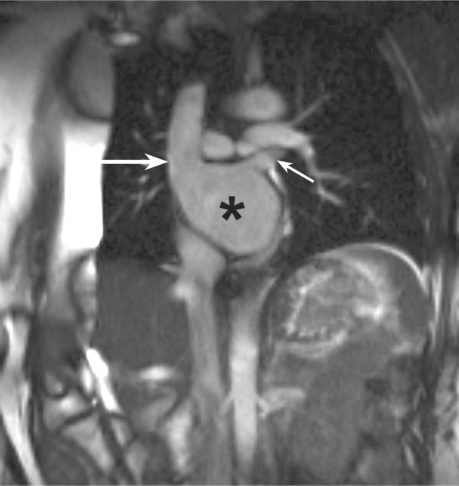

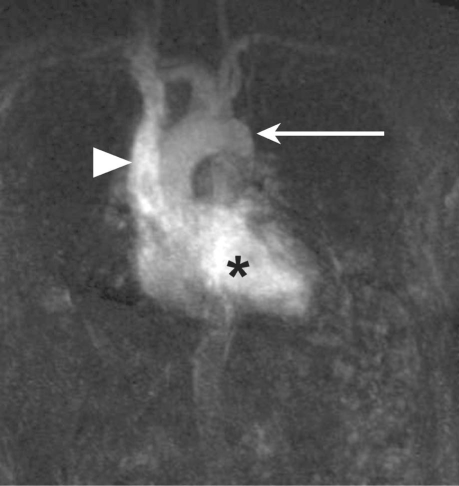

A chest radiograph showed nothing unusual. An electrocardiogram (ECG) revealed left ventricular hypertrophy and LA enlargement. The patient underwent contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) for investigation of the hypoxia, under pulmonary embolism protocol. Contrast medium was administered intravenously through a peripheral venous catheter in the right upper extremity. No contrast was detected in the pulmonary arterial system. Contrast was present in the SVC, LA, left ventricle, and aorta; however, the right heart was largely unopacified except for a small blush of contrast at the interatrial septum. This blush raised suspicion of an interatrial defect. It was noted that a single right SVC emptied into the LA, although the inferior vena cava (IVC) was contiguous with the right atrium. The left brachiocephalic vein connected to the right SVC with retrograde flow of contrast medium into the left brachiocephalic vein, which excluded persistent left SVC. A ventilation–perfusion scan, performed after the intravenous injection of technetium 99m macroaggregates into the right upper extremity, showed systemic radiotracer activity and microemboli in multiple, highly vascular structures (bypassing the lungs to appear in the systemic circulation) (Fig. 1). Transthoracic echocardiography (with agitated saline solution as the contrast medium) revealed opacification of the LA. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed the suspected diagnosis of an isolated anomalous connection of the right SVC to the LA (Figs. 2 and 3). Furthermore, axial and cine images clearly showed a patent foreman ovale with a flow jet across it.

Fig. 1. Images from a ventilation–perfusion scan that was performed after technetium 99m macroaggregates were injected intravenously into the right upper extremity. Radiotracer activity within the lungs (black arrows) is due to distribution through the bronchial arteries. Systemic activity is most evident in highly vascular structures, including the thyroid gland (black arrowheads), spleen (white arrowheads), kidneys (white arrows), salivary glands (white bar-tailed arrow), and breast tissue (black bar-tailed arrows).

LAO = left anterior oblique; LPO = left posterior oblique; LT LAT = left lateral; RAO = right anterior oblique; RPO = right posterior oblique; RT LAT = right lateral

Fig. 2. Steady-state, free-precession, paracoronal magnetic resonance image shows the superior vena cava (large arrow) and the left superior pulmonary vein (small arrow) emptying into the left atrium (asterisk). The inferior vena cava empties separately into the right atrium.

Fig. 3. Steady-state, free-precession, contrast-enhanced, coronal magnetic resonance image (maximum-intensity projection) shows contrast material in the superior vena cava (arrowhead), left heart (asterisk), and proximal aorta (arrow), without opacification of the right heart or the pulmonary vasculature.

The patient experienced no postpartum complications and remained asymptomatic for 5 days while gradually being weaned from supplemental oxygen. Before discharge from the hospital, her resting oxygen saturation was 94% on room air; however, mild asymptomatic desaturation to as low as 91% occurred when she walked. Although this anomaly and its potential complications were thoroughly explained to the patient, she refused surgical correction.

Discussion

The most frequently encountered anomaly of the great veins is a persistent left SVC that drains into the coronary sinus.2 In a 1975 Mayo Clinic review,1 SVC drainage into the LA was found to occur in approximately 0.5% of congenital cardiac cases. There have been 19 reported cases of right SVC drainage into the LA, mostly in children. Ours is the 5th reported adult case of isolated drainage of the right SVC into the LA, and only the 3rd to present asymptomatically.3–6 Although clinical presentations in the medical literature have been variable, most adult patients present either with cyanosis or with evidence of chronic hypoxemia due to a significant right-to-left shunt volume that is equal to one third of the systemic venous return.7

We believe that our patient is the first to have been diagnosed during the peripartum period with isolated right SVC drainage to the LA. Park and colleagues5 and King and Plotnick6 also reported asymptomatic adult patients with such drainage. It is unknown why some people are able to tolerate this abnormality. Rosenkranz and associates8 calculated a right SVC-to-LA shunt volume of approximately 15% in the presence of persistent left SVC, which in theory allows for better clinical tolerance. In 1961, Meadows and co-authors9 reported the case of a 37-year-old man who, while undergoing evaluation for long-standing cyanosis, clubbing, and polycythemia, was diagnosed with isolated anomalous drainage of the IVC to the LA. In view of the patient's normal heart and no diffuse pulmonary disease, the authors believed that the cyanosis and clubbing suggested pulmonary arteriovenous fistula. The absence of right ventricular hypertrophy upon ECG and normal right ventricular pressure upon catheterization constituted additional evidence. The likeliest diagnosis, they concluded, was an isolated anomalous connection of a great vein to the LA.9 The shunted blood from these anomalous venous connections causes volume overload, as is evidenced by left ventricular hypertrophy upon ECG. The severity of the hypertrophy varies in most patients who have anomalous venous connection to the LA, depending on the volume of shunted blood.

The precise embryologic mechanism of isolated right SVC insertion into the LA is unknown. The original theory by Kirsch and colleagues10 in 1961 encompassed an abnormal position of the right horn of the sinus venosus, involving “relative leftward and cephalic distortion that resulted in placing the aperture of the SVC alone in the LA.” An alternative theory11 postulated that the cephalic portion of the right valve of the sinus venosus fuses with the atrial septum superior to the coronary sinus inlet, forming a seal that prevents the SVC from draining into the right atrium. In 2003, Van Praagh and associates12 reported observations from echocardiographic and postmortem anatomic findings in instances of multiple sinus venosus defects. An SVC type of sinus venosus defect was believed to result from a deficiency in the wall that is shared by the right SVC and the right upper pulmonary veins. The interatrial communication of a sinus venosus defect is not a defect in the atrial septum; rather, it involves drainage of the LA orifice of unroofed pulmonary veins into the right SVC or right atrium. An isolated right SVC-to-LA anomaly forms upon a combination of predominant blood flow between those structures and an atresia that affects the right SVC-to-right atrial orifice.12

Isolated right SVC-to-LA drainage should be considered in the differential diagnosis of hypoxemia, along with primary lung disease, intracardiac right-to-left shunt, pulmonary arteriovenous malformation, pulmonary embolus, hemoglobinopathy, and methemoglobinemia.13 Once the SVC is found to enter the LA, commonly associated malformations should be excluded. Cardiac malformations include atrial or ventricular septal defect, single atrium or single ventricle, Eisenmenger complex, tetralogy of Fallot, and transposition of the great vessels. Associated extracardiac abnormalitiesinclude coarctation of the aorta, pulmonary arterio-venous fistula, patent ductus arteriosus, and abnormalities of the IVC.14

Over the last half-century, technological advances have enabled diagnosis of congenital cardiac anomalies with increasing frequency by use of noninvasive techniques. Identification of isolated SVC-to-LA connection was originally described in 1956 by Wood,15 who used cardiac catheterization to establish the diagnosis. In 1973, radionuclide angiocardiography was the 1st noninvasive method to be used in conjunction with cardiac catheterization as the confirmatory test.3 As echocardiography emerged in the early 1980s, M-mode and 2-dimensional contrast echocardiography were used to aid in establishing the diagnosis; however, echocardiography is limited by operator variability and poor acoustic windows.16,17 Cardiac MRI and contrast-enhanced chest CT have emerged as powerful noninvasive tools by which to evaluate cardiac anomalies. Cardiac MRI was first used in a confirmatory fashion in 1998 by Rosenkranz and coworkers8 after the diagnosis of SVC drainage into the LA was made by cardiac catheterization. In 2007, Aminololama-Shakeri and co-investigators13 reported the use of contrast-enhanced chest CT to diagnose this anomaly, followed by cardiac catheterization in order to exclude other malformations. We believe that ours is the 1st report of cardiac MRI used solely—without cardiac catheterization—to establish the diagnosis of an isolated SVC-to-LA condition noninvasively.

Any connection between the venous and arterial systems poses a substantial risk of brain abscess and paradoxic embolization.18 Twenty percent of reported cases that involved drainage of the right SVC into the LA were complicated by brain abscesses.5,6,19 Schick and colleagues20 reported the case of a 46-year-old man who, after refusing surgical correction at the time of diagnosis, died 3 years later of a right frontal brain abscess. Most reported pediatric patients have undergone surgical correction. A review of cases in adults reveals that less symptomatic patients are more likely to decline surgical correction. Regardless of clinical presentation, surgical correction is indicated once the diagnosis of a systemic venous connection to the LA is determined.20 Of note, intravenous infusions that use veins of the upper body should be avoided once a patient with this anomaly is recognized.4

Acknowledgments

We thank Michael E. Daniel, MD, and Spencer T. Sincleair, MD, of the Department of Radiology, Scott & White Hospital, for their assistance with imaging and image interpretation.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Shawn J. Skeen, MD, Department of Internal Medicine, Scott & White Hospital, 2401 S. 31st St., Temple, TX 76508

E-mail: sskeen@swmail.sw.org

References

- 1.de Leval MR, Ritter DG, McGoon DC, Danielson GK. Anomalous systemic venous connection. Surgical considerations. Mayo Clin Proc 1975;50(10):599–610. [PubMed]

- 2.Buirski G, Jordan SC, Joffe HS, Wilde P. Superior vena caval abnormalities: their occurrence rate, associated cardiac abnormalities and angiographic classification in a paediatric population with congenital heart disease. Clin Radiol 1986; 37(2):131–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Park HM, Smith ET, Silberstein EB. Isolated right superior vena cava draining into left atrium diagnosed by radionuclide angiocardiography. J Nucl Med 1973;14(4):240–2. [PubMed]

- 4.Ezekowitz MD, Alderson PO, Bulkley BH, Dwyer PN, Watkins L, Lappe DL, et al. Isolated drainage of the superior vena cava into the left atrium in a 52-year-old man: a rare congenital malformation in the adult presenting with cyanosis, polycythemia, and an unsuccessful lung scan. Circulation 1978; 58(4):751–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Park HM, Summerer MH, Preuss K, Armstrong WF, Mahomed Y, Hamilton DJ. Anomalous drainage of the right superior vena cava into the left atrium. J Am Coll Cardiol 1983; 2(2):358–62. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.King RE, Plotnick GD. Isolated right superior vena cava into the left atrium detected by contrast echocardiography. Am Heart J 1991;122(2):583–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Levy SE, Blalock A. Fractionation of the output of the heart and of the oxygen consumption of normal unanesthetized dogs. Am J Physiol 1937:118;368-71.

- 8.Rosenkranz S, Stablein A, Deutsch HJ, Verhoeven HW, Erdmann E. Anomalous drainage of the right superior vena cava into the left atrium in a 61-year-old woman. Int J Cardiol 1998;64(3):285–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Meadows WR, Bergstrand I, Sharp JT. Isolated anomalous connection of a great vein to the left atrium. The syndrome of cyanosis and clubbing, “normal” heart, and left ventricular hypertrophy on electrocardiogram. Circulation 1961;24:669–76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Kirsch WM, Carlsson E, Hartmann AF Jr. A case of anomalous drainage of the superior vena cava into the left atrium. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1961;41:550–6. [PubMed]

- 11.Braudo M, Beanlands DS, Trusler G. Anomalous drainage of the right superior vena cava into the left atrium. Can Med Assoc J 1968;99(14):715–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Van Praagh S, Geva T, Lock JE, Nido PJ, Vance MS, Van Praagh R. Biatrial or left atrial drainage of the right superior vena cava: anatomic, morphogenetic, and surgical considerations–report of three new cases and literature review. Pediatr Cardiol 2003;24(4):350–63. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Aminololama-Shakeri S, Wootton-Gorges SL, Pretzlaff RK, Reyes M, Moore EH. Right-sided superior vena cava draining into the left atrium: a rare anomaly of systemic venous return. Pediatr Radiol 2007;37(3):317–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Perloff JK. The clinical recognition of congenital heart disease. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2003. p. 563.

- 15.Wood PH. Diseases of the heart and circulation. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1956. p. 457.

- 16.Truman AT, Rao PS, Kulangara RJ. Use of contrast echocardiography in diagnosis of anomalous connection of right superior vena cava to left atrium. Br Heart J 1980;44(6):718–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Tomoe A, Yoshida Y, Ogata H, Chen HC, Fukuda M. Peripheral contrast echocardiographic findings of anomalous drainage of the right superior vena cava into the left atrium. Tohoku J Exp Med 1980;130(4):353–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Shapiro EP, Al-Sadir J, Campbell NP, Thilenius OG, Anagnostopoulos CE, Hays P. Drainage of right superior vena cava into both atria. Review of the literature and description of a case presenting with polycythemia and paradoxical embolization. Circulation 1981;63(3):712–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Thivolle P, Munsch RC, Veillas G, Dahoun A, Berger M. Cardiopulmonary flow studies show venous return from upper half of body passing directly to left atrium. J Nucl Med 1980; 21(3):293–4. [PubMed]

- 20.Schick EC Jr, Lekakis J, Rothendler JA, Ryan TJ. Persistent left superior vena cava and right superior vena cava drainage into the left atrium without arterial hypoxemia. J Am Coll Cardiol 1985;5(2 Pt 1):374–8. [DOI] [PubMed]