Abstract

The effects of microwave irradiation (2.45 GHz, 200 W) on glycosylation promoted by a solid super acid in supercritical carbon dioxide was investigated with particular attention paid to the structure of the acceptor substrate. Because of the symmetrical structure and high diffusive property of supercritical carbon dioxide, microwave irradiation did not alter the temperature of the reaction solution, but enhanced reaction yield when aliphatic acceptors are employed. Interestingly, the use of a phenolic acceptor under the same reaction conditions did not show these promoting effects due to microwave irradiation. In the case of aliphatic diol acceptors, the yield seemed to be dependent on the symmetrical properties of the acceptors. The results suggest that microwave irradiation do not affect the reactivity of the donor nor promoter independently. We conclude that the effect of acceptor structure on glycosylation yield is due to electric delocalization of hydroxyl group and dielectrically symmetric structure of whole molecule.

Keywords: glycosylation, microwave, super solid acid, supercritical carbon dioxide, dielectric constant, electric delocalization, symmetric structure

1. Introduction

Since Fischer glycosylation was first used in 1893 [1], acid promoted chemical glycosylation is a central process in the synthesis of glycoside [2]. Despite social demand for a reduction in consumption in chemical processes, the combination of organic solvents and soluble promoters, which are both harmful for the environmental and difficult to separate from other chemicals, were most commonly used in mainstream chemical glycosylation processes [2]. Recently, some pioneering efforts resulted in the replacement of the promoter and solvent of glycosylation process with environmental friendly chemicals, using solid super acids [3,4] and ionic liquids [5]. Because of the increasing importance of glycoconjugates in life science, an environmentally benign and efficient glycosylation method is in high demand for practical and industrial scale production of natural and unnatural glycosides. Natural product origin or enzymatic synthesized glycosides have been recognized as a much more sustainable protocol [6–8]. However, chemical syntheses of the glycoside bond still have a large advantage over other methods due to their structural diversity and functionalization of product oligosaccharides. Chemo–enzymatic synthetic methods (i.e., enzymatic modification of chemically synthesized core oligosaccharide) seem to meet the needs for practical preparation of a large variety of glycoconjugates to be used as bio–probe and drug seeds [9–12]. This means that making the chemical process sustainable is an important requirement. Previously, we have reported a glycosylation process which uses the combination of a solid super acid and supercritical (sc)CO2. Not only was this simple and organic solvent–free separation process but it also demonstrated higher reactivity than conventional organic solvents as a result of the good compatibility between surface of the solid acid and the diffusion properties of scCO2 [13]. As CO2 has a critical point close to ambient temperature (Tc = 31 °C, Pc = 7.4 MPa) and is nonflammable, nontoxic, inexpensive and scCO2 are attractive alternative of common organic solvent.

Microwave (MW) irradiation is also an attractive choice to promote reactions and is an energy effective heating method compared to conventional heat conduction type methods (such as an oil bath) due to the direct heating of the reaction mixture. Additionally, MW irradiation often shows an acceleration of the reaction rate and product selectivity, thereby improving the reaction time and total yield respectively [14]. MW-assisted glycosylations promoted by acid catalysts were also reported for Fischer glycosylation [15], and an acetal exchange reaction from a methyl glycoside type donor [16], glycosyl acetate type donor [17,18], and a trichloroimidate type donor [19]. However MW-assisted glycosylation in a nonpolar solvent such as scCO2 has not been reported. Polar solvent are chosen for MW-assisted synthesis because the mechanism of microwave heating is dielectric losses of the irradiated material, and the dielectric constant (ɛ) of the solvent is affected in MW-assisted solution phase synthesis [20]. Both liquid and supercritical CO2 have extremely low dielectric constants (ɛ = 1~1.5) [21,22] and scCO2 itself is supposed to be inert to MW irradiation. Normally, the MW inert solvent was avoided for MW assisted synthesis without passive heating by the presence a strong MW absorbing material [23]. To the best of our knowledge, MW heating in scCO2 was reported only for extraction process to heat solid material directly [24]. However, our previous study suggested a nonthermal effect of MW irradiation for glycosylation processes [17] using temperature controlled MW irradiation by simultaneous cooling [25]. It is interesting how the MW inert and high thermal diffusion properties of scCO2 are affected to the MW-assisted reactions. It is believed that the reaction system also show alternative reactivity without thermal elevation.

In this study, we have focused on the MW effects on glycosylation promoted by solid acid in scCO2.

2. Results and Discussion

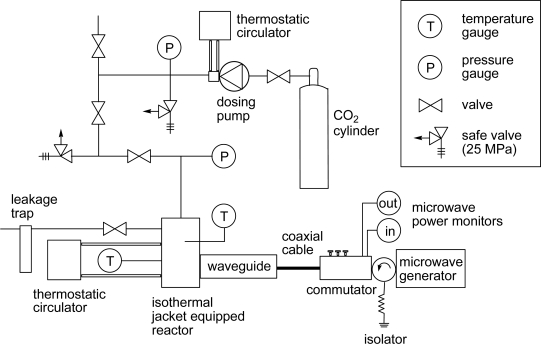

A novel reaction apparatus equipped with MW controller, liquid CO2 controller, thermo controller, and pressure controller was developed and examined in this study. Figure 1 shows schematic view of the apparatus. The MW generator yields 2.45 GHz and ~ 3.0 kW, and single mode MW irradiation was selected for stable radiation into the reactor [25]. The MW absorption efficiency of the reaction solutions was monitored by a MW power monitor. The reaction temperature was regulated by an isothermal jacket on the reactor and was monitored at the alloy wall of the reactor and at the scCO2 solution area directly using metal sheathed thermocouples.

Figure 1.

Schematic view of microwave-assisted scCO2 reactor.

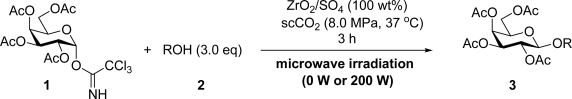

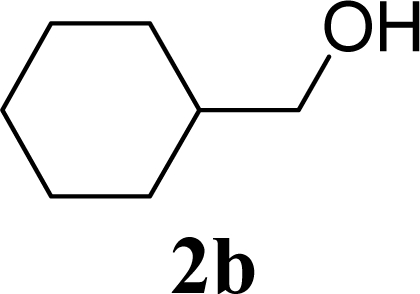

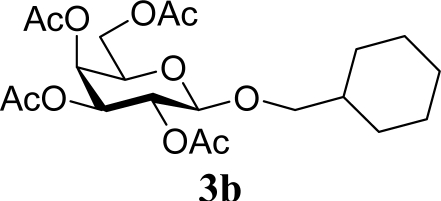

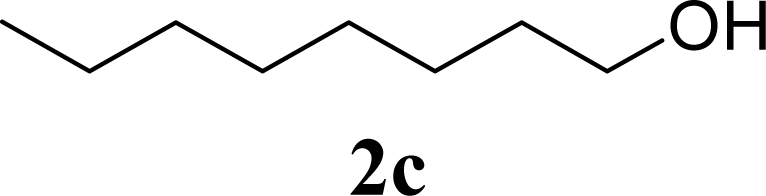

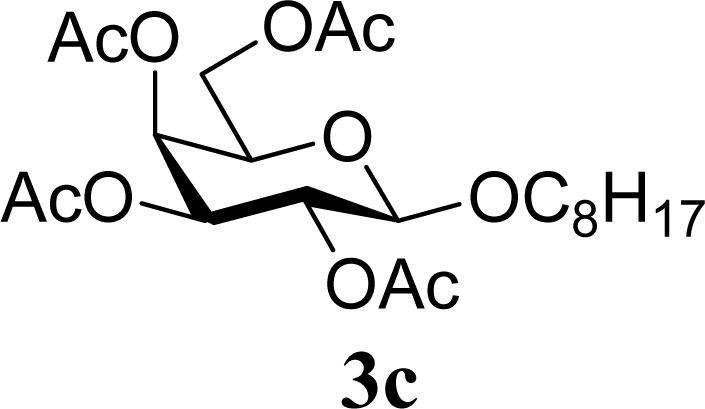

As shown in Schemes 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-α-d-galactopyranose trichloroacetimidate (1) [26] was used as a common glycosyl donor substrate in this study. One hundred mg of the glycosyl donor 1 with various glycosyl acceptors (3 equivalents for 1) were reacted with sulfated zirconia (ZrO2/SO4; 100 wt% for 1) under MW irradiation (0 or 200 W) in scCO2 (37 °C, 8.0 MPa) for 3 h to give glycoside 3. All reactions were conducted twice and each yield was calculated from the weight of the product 3 after purification by column chromatography. In all reactions in this study, the temperature of the reaction solutions did not show detectable changes when subject to 200 W of MW irradiation. It is believed that that the dielectric and diffusion properties of scCO2 minimize the temperature changes in the solution due to exposure to MW irradiation.

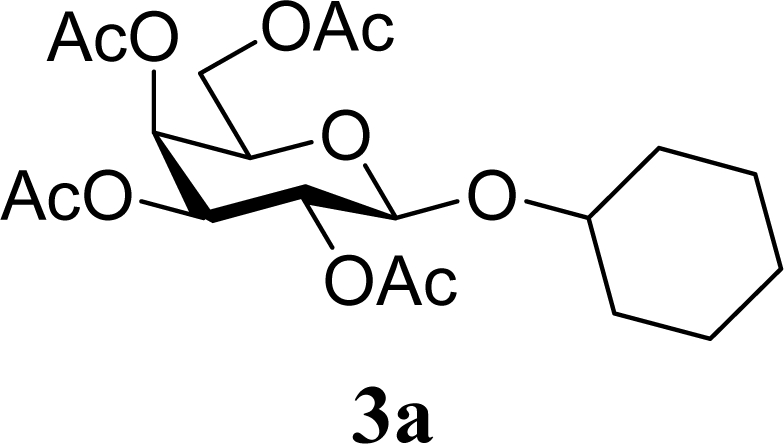

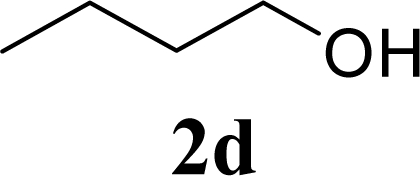

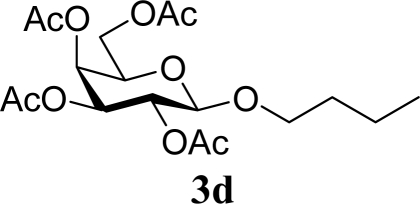

Table 1 indicates the result of the glycosylation reactions with aliphatic alcohols 2a-d. Without MW irradiation, β-glycoside 3a [27], 3b, 3c [28] and 3d [28] were isolated in 53~65% yields. With MW irradiation, the yields of 3a-d showed considerable increase in the 12~26% range. The increasing range of each product due to MW irradiation (3d, 3a, 3b, 3c) seems to be reflected in the order of molecular polarity of each acceptor.

Table 1.

Glycosylation of 1 and aliphatic glycosyl acceptors 2a–d promoted by ZrO2/SO4 in scCO2 with or without MW irradiation.

| Entry | Acceptor 2 | MW (W) | Glycoside 3 | Yield [1st, 2nd] (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

0 |  |

53 [51,55] |

| 2 | 2a | 200 | 3a | 71 [69,72] |

| 3 |  |

0 |  |

54 [52,55] |

| 4 | 2b | 200 | 3b | 68 [68,67] |

| 5 |  |

0 |  |

65 [68,62] |

| 6 | 2c | 200 | 3c | 77 [80,74] |

| 7 |  |

0 |  |

60 [58,61] |

| 8 | 2d | 200 | 3d | 86 [84,87] |

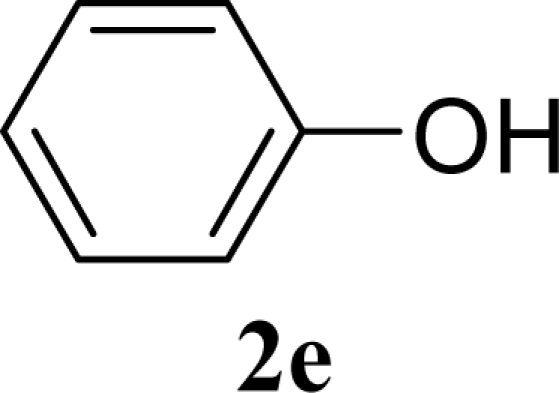

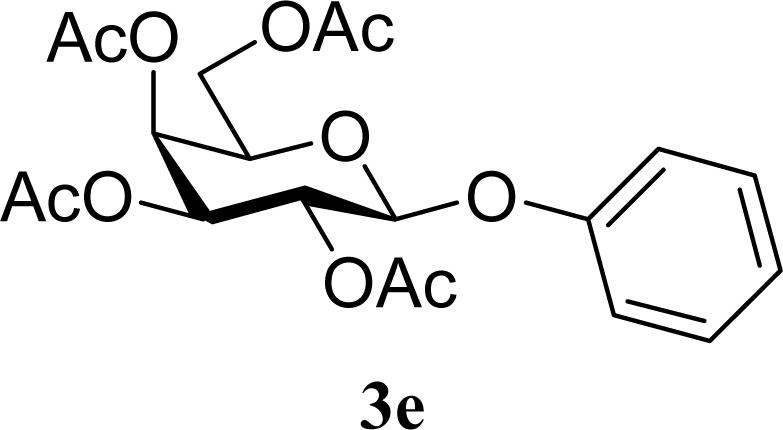

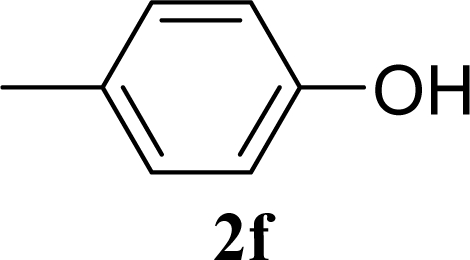

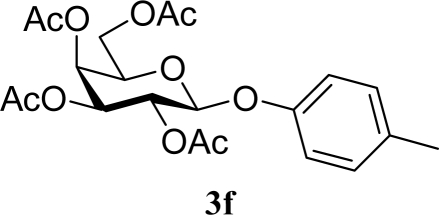

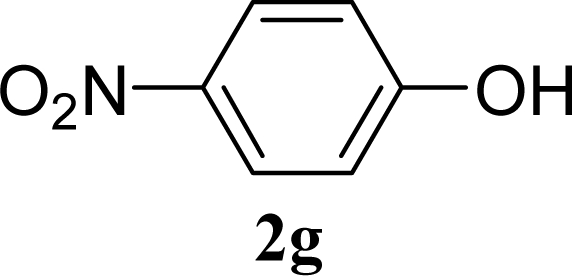

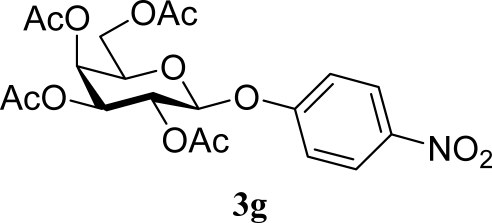

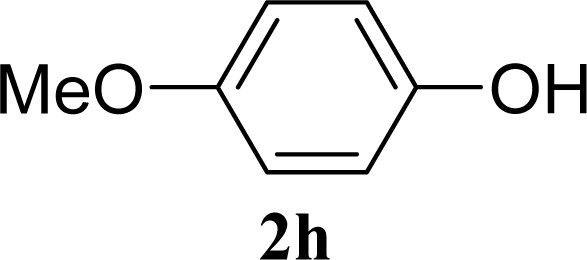

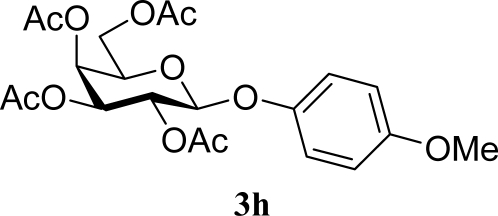

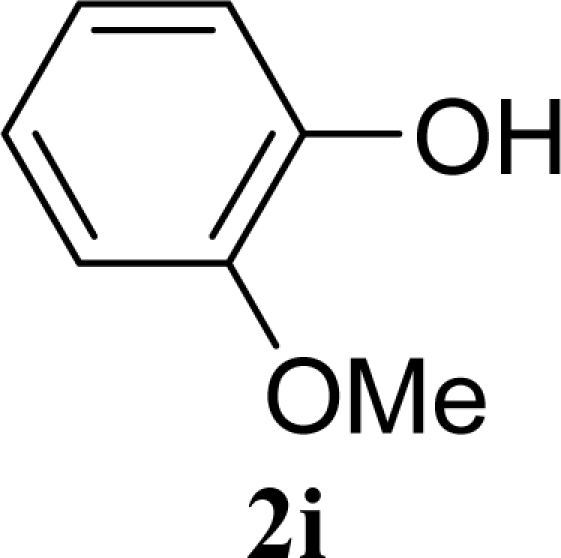

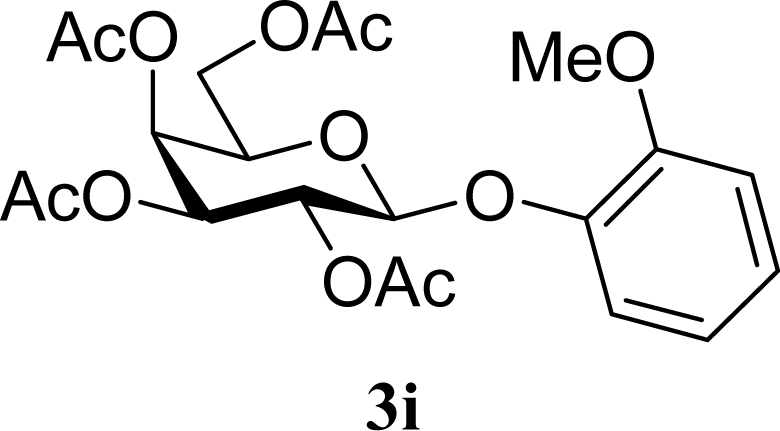

Table 2 indicates the results of the glycosylation reactions with phenolic alcohols 2e–i. Without MW irradiation, β-glycoside 3e [29], 3f [29], 3g [29], 3h [30] and 3i [30] were isolated in 5~43% yields. Among the p-substituted acceptors 2e–h, the electrostatic properties of the p-substitution groups clearly affected the yields of the glycoside 3e–h that were increased by electron donating substitution groups (-OMe, -Me) and decreased by withdrawing substitution group (-NO2) compared to unsubstituted phenyl glycoside 3e. The order of the yields of the glycoside 3e–h was inverted to the yields of SN2 type reactions between α-galactosyl bromide and phenoxides [29]. The position of the substitution group also affected the yield and the o-OMe phenol 3i showed lower yield than p-OMe phenol 3h. In contrast to the aliphatic glycoside 3a–d, obvious effects of MW irradiation were not observed in the yields of all phenolic glycosides 3e–i, which were not affected by the difference in dielectric constant nor the electron density on the phenolic hydroxyl group in 2e–i. Electron delocalization, which is the obvious difference between aliphatic acceptors 2a–d and phenolic acceptors 2e–i, is believed to be the reason for differences between them.

Table 2.

Glycosylation of 1 and phenolic glycosyl acceptors 2e–i promoted by ZrO2/SO4 in scCO2 with or without MW irradiation.

| Entry | Acceptor 2 | MW (W) | Glycoside 3 | Yield [1st, 2nd] (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 |  |

0 |  |

14 [12,15] |

| 10 | 2e | 200 | 3e | 20 [17,23] |

| 11 |  |

0 |  |

41 [49,33] |

| 12 | 2f | 200 | 3f | 39 [39,38] |

| 13 |  |

0 |  |

5 [6,4] |

| 14 | 2g | 200 | 3g | 3 [5,1] |

| 15 |  |

0 |  |

43 [42,44] |

| 16 | 2h | 200 | 3h | 40 [42,38] |

| 17 |  |

0 |  |

24 [26,22] |

| 18 | 2i | 200 | 3i | 22 [24,20] |

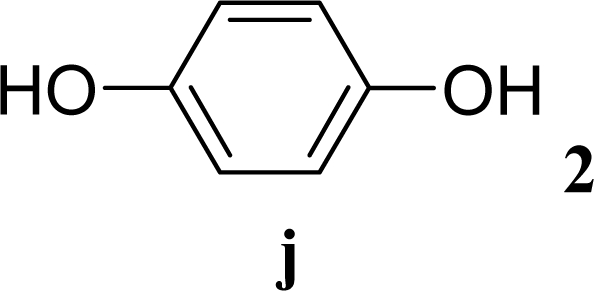

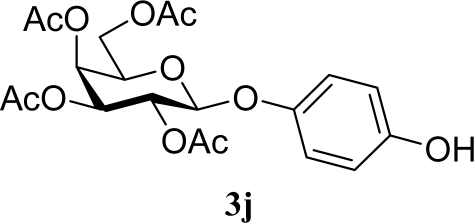

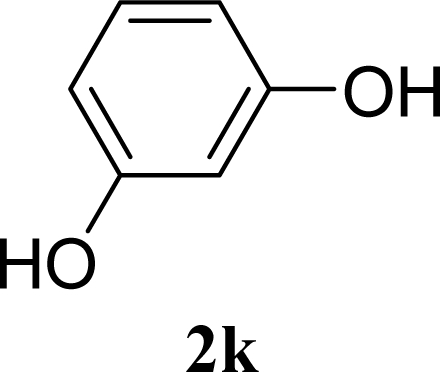

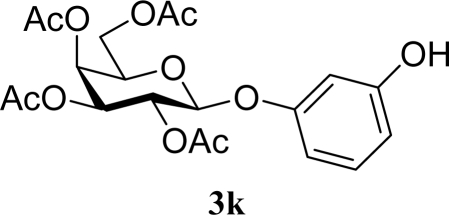

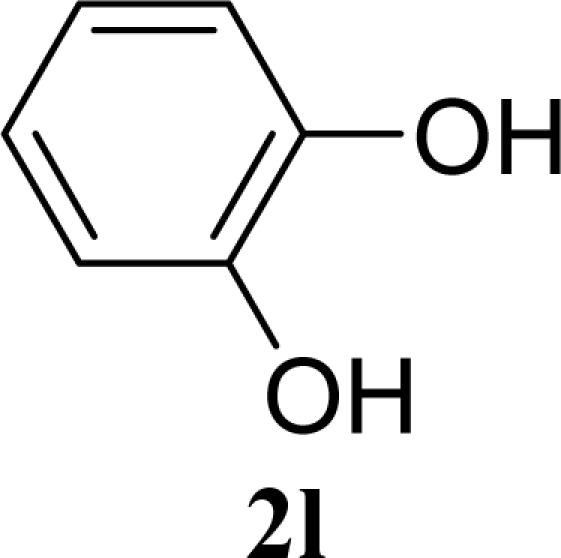

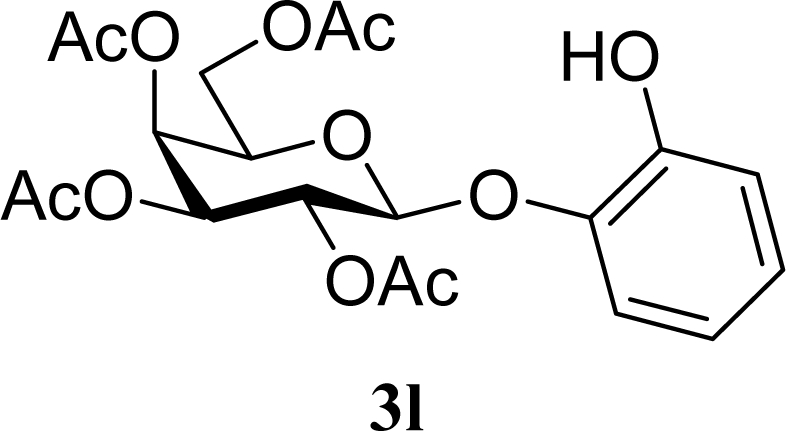

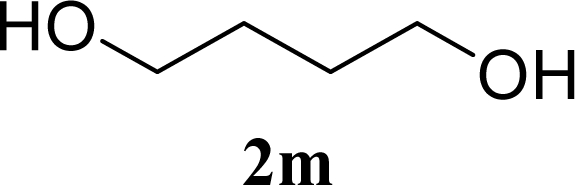

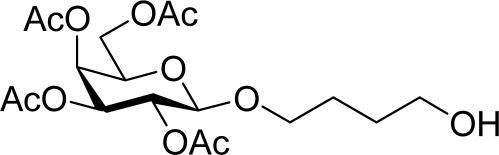

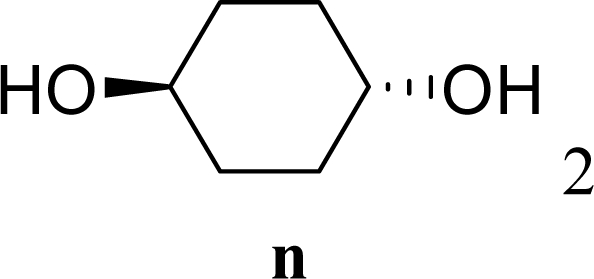

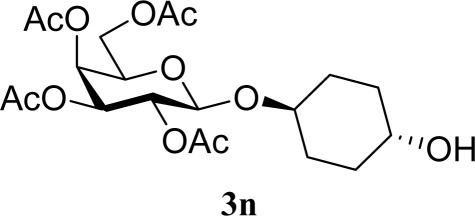

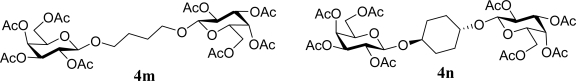

Table 3 indicates the result of the glycosylation reactions with diols 2j–n. Without MW irradiation, monoglycosylated products 3j [31], 3k [32], 3l [32], 3m, and 3n were isolated in 6~20% yields. Diglycosylated products were also isolated from the reaction with aliphatic diol acceptors to give 4m [33] and 4n in 12 and 17% yields respectively but were not detected from the reaction with phenolic diols 2j–l. In contrast to the methoxyphenyl glycoside 3h and 3i, the yield of hydroxyphenyl glycoside 3j and 3l showed an increase due to a change in position of the substitution group from para to ortho. In the case of aliphatic alcohols, the sums of the glycoside yields of 3m and 4m, 3n and 4n were decreased from the yields of 3d and 3a (corresponding products from monools) respectively. Although it made us suspect the solubility of the diols (especially 2m), it was confirmed that 2m was dissolved in scCO2 under the condition of glycosylation using window equipped reactor [16]. Among the phenolic diols 2j–l, obvious MW effects were not observed in the yields of the monoglycosylated product 3j–l and diglycosylated products also were not obtained. 1,4–Butandiol 2m showed clear MW effects regarding an increase in the yields of both mono- and diglycosylated product 3m and 4m in the 18 and 6% ranges respectively. In the case of trans-1,4-cyclohexanediol 2n which is a conformationally-rigid symmetric diol, however, the MW effect was not observed in the yields of both products 3n nor 4n. This unchanged reactivity for the aliphatic diol 2n indicates that the dielectric inertness by symmetrical conformation also affected to the MW effect. These results also indicate that MW irradiation did not affect the activity of the glycosyl donor 1 or the promoter ZrO2/SO4, or at least harmonized the activation of acceptors 2 and the donor 1 or promoter were required for increasing reactivity by MW. A polar solvent may also work as a medium for the harmonization of inter-reactants to accelerate reactions under MW irradiation.

Table 3.

Glycosylation of 1 and diol-type glycosyl acceptors 2j–n promoted by ZrO2/SO4 in scCO2 with or without MW irradiation.

| Entry | Acceptor 2 | MW (W) | Monoglycosylated product 3 | Yield of 3 [1st, 2nd] (%) | Yield of diglycosylated product 4 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19 |  |

0 |  |

6 [7,4] | n. d. |

| 20 | 2j | 200 | 3j | 5 [4,6] | n. d. |

| 21 |  |

0 |  |

14 [8,19] | n. d. |

| 22 | 2k | 200 | 3k | 19 [10,28] | n. d. |

| 25 |  |

0 |  |

20 [19,21] | n. d. |

| 26 | 2l | 200 | 3l | 17 [16,18] | n. d. |

| 27 |  |

0 |  |

12 [12,12] | 4ma,b 12 [11,12] |

| 28 | 2m | 200 | 3m | 30 [33,26] | 4ma,b |

| 29 |  |

0 |  |

17 [14,20] | 18 [16,20] 4na,b |

| 30 | 2n | 200 | 3n | 21 [23,19] | 17 [15,18] 4na,b 14 [10,17] |

Structure of diglycosylated product 4m and 4n.

The yields of 4m and 4n were calculated as one half molar equivalent of the glycosyl donor 1 was 100%.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Materials

Sulfated zirconia (zirconium composition is 60–70%) was purchased from Wako Chemical. The sulfated zirconia was calcined at 600 °C for 2 h before use, and cooled in a glass desiccator without the use of drying agent. All acceptors were purchased in the anhydrous form and added to the reaction mixture without any pretreatment. Advantech No. 2 filter paper was used for the separation of catalysts to stop the reactions. The yield and α/β ratio of the product was calculated from isolated yield and integral area of product anomeric protons using 1H-NMR spectroscopy (Bruker AM-500 spectrometer operating at 500.13 MHz), respectively.

3.2. General Method for Glycosylation Reactions

2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-α-d-galactopyranosyl trichroloacetoimidate (1, 100 mg, 203 μmol), acceptor 2 (3.0 eq), and ZrO2/SO4 (100 mg) were added to the reactor, which was heated to 37 °C and CO2 was introduced successively from a reservoir by a high–pressure pump. The reaction time was counted from the point at which the CO2 pressure reached 8.0 MPa. After the reaction has been sustained at 37 °C and 8.0 MPa for 3 h, CO2 was slowly leaked out. The residual solid was washed out with CHCl3. ZrO2/SO4 was removed by filtration. The filtrate was concentrated in vacuo and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography to give the glycoside 3.

Cyclohexanemethyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (3b): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): σ 5.39–5.38 (d, 1H, J = 3.3 Hz, H-4), 5.22–5.19 (dd 1H J = 8.0, 2.4 Hz, H-2), 5.03–5.00 (dd, 1H, J = 7.1, 3.5 Hz, H-3), 4.44–4.42 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz, H-1), 4.18–4.12 (m, 2H, H-6), 3.91–3.89 (t, 1H, J = 6.8 Hz, H-5), 3.74–3.71 (dd, 1H, J = 5.9, 3.5 Hz, CH2), 3.26–3.23 (dd, 1H, J = 7.1, 2.2, CH2), 2.15, 2.05, 2.04, 2.00 (s, 12H, 4 × CH3), 1.75–1.66 (m, 6H, CH2), 1.62–1.54 (m, 1H, CH), 1.24–1.22 (m, 2H, CH2), 0.93–0.90 (m, 2H, CH2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): σ 20.60, 25.71, 25.78, 26.51, 29.54, 29.70, 37.80, 61.31 (C-6), 67.27 (C-4), 69.03 (C-2), 70.59 (C-5), 71.06 (C-1), 75.96, 101.7 (C-1), 168.61, 170.00, 170.24, 170.44; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: calculated for C21H32O10Na: 467.18877, found: 467.18950 [M + Na]+.

4-Hydroxybutyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (3m): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): σ 5.39–5.38 (d, 1H, J = 3.3 Hz, H-4), 5.22–5.18 (dd, 1H, J = 8.2, 2.4 Hz, H-2), 5.03–5.01 (dd, 1H, J = 7.1, 3.4 Hz, H-3), 4.48–4.47 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz, H-1), 4.21–4.11 (m, 2H, H-6), 3.96–3.94 (m, 1H, CH), 3.92–3.90 (t, 1H, J = 6.7 Hz, H-5), 3.66–3.64 (td, J = 4.6, 1.5 Hz, 2H, CH2), 3.55–3.51 (m, 1H, CH), 2.16, 2.06, 2.05, 1.99 (s, 12H, 4 × CH3), 1.73–1.58 (m, 4H, 2 × CH2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): σ 20.59, 20.67, 20.77, 25.89, 29.33, 61.32 (C-6), 62.37, 67.11 (C-4), 68.95 (C-2), 70.00, 70.69 (C-5), 70.95 (C-3), 101.32 (C-1), 169.55, 170.20, 170.31, 170.44; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: calculated for C18H28O11Na:443.15293, found:443.15218 [M + Na]+.

Trans-4-Hydroxycyclohexyl 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (3n): 1H-NMR (600 MHz, CDCl3): σ 5.37 (s, 1H, Hz, H-4), 5.21–5.18 (t, 1H, J = 9.1 Hz, H-2), 5.03–5.00 (dd, 1H, J = 10.6, 3.3 Hz, H-3), 4.56–4.52 (d, 1H, J = 8.8 Hz, H-1), 4.24–4.04 (m, 2H, H-6), 3.89–3.87 (t, 1H, J = 6.4 Hz, H-5), 3.81–3.76 (m, 1H, CH), 3.72–3.66 (m, 1H, CH), 2.15, 2.05, 2.03, 1.99 (s, 12H, 4 × CH3), 1.88–1.45 (m, 9H, OH + 4 × CH2); 13C-NMR (150 MHz, CDCl3): σ 22.10, 22.17, 22.27, 22.33, 28.56, 30.57, 31.52, 31.93, 62.80 (C-6), 68.62 (C-4), 69.76, 70.56 (C-2), 72.10 (C-5), 72.53 (C-3), 75.65, 101.03 (C-1), 170.84, 171.73, 171.86, 171.94; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: calculated for C20H30O11Na: 469.16803, found: 469.16935 [M + Na]+.

Trans-1,4-Bis((2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-galactopyranosyl)oxy)cyclohexane (4n): 1H-NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): σ 5.39–5.38 (d, 2H, J = 3.1 Hz, 2 × H-4), 5.21–5.17 (t, 2H, J = 7.9, 2.5 Hz, 2 × H-2), 5.03–5.01 (dd, 2H, J = 7.0, 3.4 Hz, 2 × H-3), 4.55–4.53 (d, 2H, J = 7.9 Hz, 2×H-1), 4.20–4.06 (m, 4H, 2 × H-6), 3.91–3.86 (t, 2H, J = 6.2 Hz, 2 × H-5), 3.81–3.53 (m, 2H, 2 × CH), 2.20–1.95 (s, 24H, 8 × CH3), 1.94–1.36 (m, 8H, 4 × CH2); 13C-NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): σ 20.61, 20.69, 20.70, 20.75, 26.32, 28.31, 61.24 (C-6), 67.08 (C-4), 68.85 (C-2), 70.60 (C-5), 70.96 (C-3), 73.78, 98.73 (C-1), 169.49, 170.20, 170.32, 170.41; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: calculated for C34H48O20Na:799.26311, found:799.26354 [M + Na]+.

4. Conclusions

The effect of MW on glycosylation promoted by ZrO2/SO4 in scCO2 was investigated with a special focus on the differences between acceptor substrates. The temperature of the reaction mixture was not affected by MW irradiation because of the extremely low dielectric constant and diffusion properties of scCO2, which made possible the monitoring of the MW effect under minimized conditions of thermal and solvation effects. The changing range of glycosylation yield between a MW irradiated reaction and a non-microwave reaction clearly showed phenolic and aliphatic acceptors as the unaffected and affected groups, respectively. The electron delocalization of phenolic hydroxyl groups was associated with the cause of the unresponsive properties by MW. The difference of MW effects among aliphatic hydroxyl groups indicated the dielectric neutralization by symmetric conformation also related to it. A harmonized activation mechanism of acceptors 2 and the donor 1 or promoter by MW was also suggested as a cause of the non-thermal MW effect. Additional study of MW effect focused on the dielectric property of the glycosyl donor and promoter and the presence of their harmonizing effect with acceptors are under investigation.

Scheme 1.

Glycosylation conditions in this study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funding from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports and Technology of Japan for “Innovation COE Program for Future Drug Discovery and Medical Care”. This work was also supported in part by SEN-TAN, JST (Japan Science and Technology Agency).

References and Notes

- 1.Fischer E. Über die Glucoside der Alkohole. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1893;26:2400–2412. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Toshima K, Tatsuta K. Recent progress in o-glycosylation methods and its application to natural product synthesis. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1503–1531. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Toshima K, Kasumi K, Matsumura S. Novel stereocontrolled glycosidations using a solid acid, SO4/ZrO2, for direct synthesis of α- and β-mannopyranosides. Synlett. 1998:643–645. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nagai H, Sasaki K, Matsumura S, Toshima K. Environmental benign β–stereoselective glycosidations of glycosyl phosphites using a reusable heterogeneous solid acid, nomtmorillonite K-10. Carbohydr. Res. 2005;340:337–353. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sasaki K, Matsumura S, Toshima K. A novel glycosidation of glycosyl fluoride using a designed ionic liquid and its effect on the stereoselectivity. Tetrahedron Lett. 2004;45:7043–7047. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seko A, Koketsu M, Enoki Y, Ibrahim HR, Juneja LR, Kim M, Yamamoto T. Occurrence of a sialylglycopeptide and free sialylglycans in hen’s egg yolk. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1997;1335:23–32. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(96)00118-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Endo T, Koizumi S. Large-scale production of oligosaccharides using engineered bacteria. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2000;10:536–541. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(00)00127-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen X, Kowal P, Wang PG. Large-scale enzymatic synthesis of oligosaccharides. Curr. Opin. Drug Discov. Devel. 2000;3:756–763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fumoto M, Hinou H, Ohta T, Ito T, Yamada K, Takimoto A, Kondo H, Shimizu H, Inazu T, Nakahara Y, Nishimura S-I. Combinatorial synthesis MUC1 glycopeptides polymer blotting facilitates chemical enzymatic synthesis highly complicated mucin glycopeptides. J. Am. Che. Soc. 2005;127:11804–11818. doi: 10.1021/ja052521y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hanashima S, Manabe S, Ito Y. Divergent synthesis of sialylated glycan chains: Combined use of polymer support, resin capture-release, and chemoenzymatic strategies. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4218–4224. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blixt O, Vasiliu D, Allin K, Jacobsen N, Warnock D, Razi N, Paulson JC, Bernatchez S, Gilbert M, Wakarchuk W. Chemoenzymatic synthesis of 2-azidoethyl-ganglio-oligosaccharides GD3, GT3, GM2, GD2, GT2, GM1 and GD1a. Carbohydr. Res. 2005;340:1963–1972. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishimura S-I. Combinatorial syntheses of sugar derivatives. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2001;5:325–335. doi: 10.1016/s1367-5931(00)00209-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X-B, Ogawa M, Monden T, Maeda T, Yamashita E, Naka M, Matsuda M, Hinou H, Nishimura S-I. Glycosidation promoted by a reusable solid superacid in supercritical carbon dioxide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:5652–5655. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nuchter M, Ondrusehka B, Bonreth W, Gum A. Microwave assisted synthesis–A critical technology overview. Green Chem. 2004;6:128–141. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bornaghi LF, Poulsen SA. Microwave-accelerated fisher glycosylation. Tetrahedr. Lett. 2005;46:3485–3488. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoshimura Y, Shimizu H, Hinou H, Nishimura SI. A novel glycosylation concept; microwave-assisted acetal-exchange type glycosylations from methyl glycosides as donors. Tetrahedr. Lett. 2005;46:4701–4705. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shimizu H, Yoshimura Y, Hinou H, Nishimura SI. A new glycosylation method part 3: Study of microwave dffects at low temperatures to control reaction pathways and reduce byproducts. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:10091–10096. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seibel J, Hillringhaus L, Moraru R. Microwave-assisted glycosylation for the synthesis of glycopeptides. Carbohydr. Res. 2005;340:507–511. doi: 10.1016/j.carres.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen K, Worm-Leonhard K, Olsen P, Hoel A, Jensen KJ. Reconsidering glycosylations at high temperature: precise microwave heating. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005;3:3966–3970. doi: 10.1039/b511266d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hosseini M, Stiasni N, Barbieri V, Kappe CO. Microwave-assisted asymmetric organocatalysis. A probe for nonthermal microwave effects and the concept of simultaneous cooling. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:1417–1424. doi: 10.1021/jo0624187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moriyoshi T, Kita T, Usaki Y. Static relative permittivity of carbon-dioxide and nitrous-oxide up to 30 Mpa. Ber. Bunsenges. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:589–596. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michels A, Kleerekoper L. Measurements on the dielectric constant of CO2 at 25 °C, 50 °C and 100 °C up to 1700 atmospheres. Physical. 1939;7:586–590. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kremsner JM, Kappe CO. Silicon carbide passive heating elements in microwave-assisted organic synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2006;71:4651–4658. doi: 10.1021/jo060692v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Staudt R, Nitzsche J, Harting P. Supercritical fluid extraction using microwave heating. In: Brunner G, editor. Proceedings 6th International Symposium on Supercritical Fluids; Versailles, France. April 2003; [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kappe CO, Dallinger D. Controlled microwave heating in modern organic synthesis: Highlights from the 2004–2008 literature. Mol. Divers. 2009;13:71–193. doi: 10.1007/s11030-009-9138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schmidt RR, Stumpp M. Glycosylimidates. 8. Synthesis of 1-thioglycosides. Liebigs Ann. Chem. 1983;7:1249–1256. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroeder LR, Counts KM, Haigh FC. Stereoselectivity of Koenigs-Knorr syntheses of alkyl β-d-galactopyranoside and β-d-xylopyranoside peracetates promoted by mercuric bromide and mercuric oxide. Carbohydr. Res. 1974;37:368–372. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsui DSK, Gorin PAJ. Methods for the preparation of alkyl 1,2-orthoacetates of d-glucopyranose and d-galactopyranose in high yield. Carbohydr. Res. 1985;144:137–147. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dess D, Kleine HP, Weinberg DV, Kaufmann RJ, Sidhu RS. Phase-transfer catalyzed synthesis of acetylated aryl β-d-glucopyranosides and aryl β-d-galactopyranosides. Synthesis. 1981:883–885. [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Bruyne CK, Wouters-Leysen J. Synthesis of substituted phenyl β-d-galactopyranosides. Carbohyd. Res. 1971;18:124–126. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamago S, Hashidume M, Yoshida JI. A new synthetic route to substituted quinones by radical-mediated coupling of organotellurium compounds with quinines. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:6805–6813. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng SQ, Li L, Wu JW, An Y, Cheng TM, Cai MS. Studies on glycosides IV. Synthesis of arbutin analogs. Acta. Chim. Sin. 1989;47:512–515. [Google Scholar]

- 33.DeFrees SA, Kosch W, Way W, Paulson JC, Sabesan S, Halcomb RL, Huang DH, Ichikawa Y, Wong CH. Ligand recognition by e-selectin: Synthesis, inhibitory activity and conformational analysis of bivalent sialyl lewis x analogs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:66–79. [Google Scholar]