Abstract

Background

There are no reported head-to-head comparative assessments of health care in any two countries by people who have experienced both. We sought to report the experiences and views of Americans living in Canada who have used both health care systems as adults.

Methods

We surveyed a sample of Americans living in Canada. We used 5 communication strategies to obtain the sample and asked respondents to provide experience-based ratings of various dimensions of health system quality.

Results

The survey was completed by 310 people who met the inclusion criteria. This group was highly educated (58% with a master's degree or higher) and prosperous (51% of households had a yearly income > $100,000). Seventy-four percent rated the overall quality of US health care as excellent or good, compared with 50% who gave this rating to Canadian health care. Most preferred the American system for emergency, specialist, hospital and diagnostic services. Respondents rated the Canadian system more highly for access to drug therapy and expressed similar views of the two systems with respect to care from a family physician. The features of the US system rated most positively were timeliness and quality; those rated most highly in the Canadian system were equity and cost-efficiency. The most negatively viewed features of the US system were cost/inefficiency and inequity; those of the Canadian system were wait times and personnel shortages. Although respondents generally rated the components of the US system more favourably than Canada's, when asked which system they preferred overall, 45% chose the US system and 40% chose Canada's.

Conclusion

Americans living in Canada generally rated the US health care system as being better than the Canadian system. However, they acknowledged the inefficiency and inequity of the US system, and nearly half preferred the Canadian system despite its perceived problems.

Introduction

The comparative merits of various nations' health care systems are often, and sometimes heatedly, debated. Empirical comparisons are typically compilations of survey respondents' self-reported experiences or perceptions in their own countries.1-6 This method assumes that study participants are equivalent to groups randomly assigned to experience various nations' health care systems, and that observed differences are attributable entirely to the systems themselves. This overlooks differences in culture, preferences and expectations that may affect self-reported experiences of health care and overall system assessments.

Experience-based comparison is a stronger method. There are no reported studies of head-to-head comparisons of health care in any two countries by people who have experienced both. This study reports the experiences and views of Americans living in Canada who have used both health care systems as adults.

The objectives of the study were to obtain the views of Americans living in Canada on their experiences of care in both countries, their absolute and relative ratings of the quality of various dimensions of care in both countries, and their overall assessments of the two countries' health care systems. The secondary objective was to establish the feasibility and validity of a method to add a new dimension and richness to the field of comparative health systems analysis.

Methods

Target participants

We targeted Americans who had been responsible for their own health care as adults for at least 2 years before coming to Canada and who had been living in Canada for at least 2, but no more than 5, years (to ensure reasonable recall of experiences in both systems). We asked potential respondents to self-screen for eligibility based on these characteristics.

Methods for recruiting participants

Americans living in Canada are a "hard to reach" population. Communication with provincial and federal agencies confirmed that there is no accessible database that identifies émigrés by country of origin and current address. Building on approaches used in other contexts,7-9 we developed a novel method incorporating 5 techniques to solicit responses. First, through the offices of the University of Calgary, Faculty of Medicine, Office of Communications, we held a live media conference supplemented by a nationwide media release. Second, 3 weeks later, we distributed nationally an op-ed piece that outlined the purpose, uniqueness and importance of the study and how to participate. Third, we placed paid advertisements for the study in 6 newspapers: The Globe and Mail and National Post (both national newspapers based in Toronto), the Calgary Herald and Calgary Sun, and The Vancouver Sun and The Province (Vancouver). These 3 cities are home to 31% (79,000) of the 258,000 émigrés to Canada from the United States10 and about 40% of recent arrivals. (Based on 1996–2001 immigration data, 12,300 of 29,750 arrivals settled in the Toronto, Vancouver and Calgary census metropolitan areas.) Fourth, we sent the study information to US consulates and to the organizations Democrats Abroad Canada and Republicans Abroad Canada and asked them to forward it to their membership or contact lists. Fifth, the survey website encouraged visitors to send the information to other people whom they thought would meet the eligibility criteria. (This recruitment technique is often referred to as "the snowball method.")

We developed and pre-tested an Internet-based survey instrument to gather information on respondents' demographic characteristics, reasons for moving to Canada, health status, use and personal costs of health care, assessments of the timeliness and quality of care in several categories in both countries, and overall system preferences. We assumed that a very high percentage of the target audience would be connected to the Internet, and that respondents might be more willing to answer potentially sensitive questions anonymously in electronic format rather than in personal interviews. We posted the survey on the Internet from 6 April 2005 until 31 July 2005 and installed a toll-free telephone number to handle inquiries and provide technical assistance.

Our study received ethical approval from the Health Research Ethics Board of the University of Calgary.

Data analysis

We estimated a priori that 200 respondents would be sufficient to generate relatively narrow confidence intervals around estimates of proportions (ranging from ± 4% to ± 7% for proportions of 10% and 50%, respectively) and that a larger sample would permit certain between-group comparisons. We used simple descriptive statistics to analyze the data, reporting proportions and 95% confidence intervals in most instances. We also used chi-square tests to compare perceptions between groups categorized by length of time since arrival in Canada, health status, household income and province of residence.

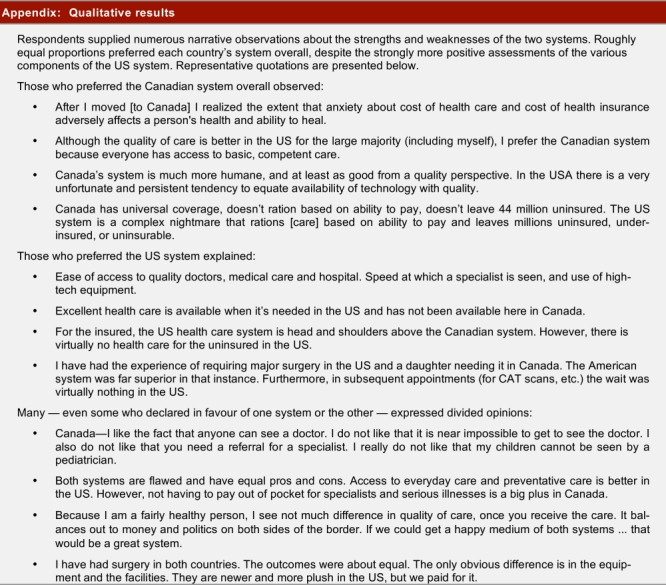

Respondents also provided qualitative information in open-text form. We grouped these data thematically and report the general findings in the following section (a more detailed overview, including illustrative quotations, is reported in the Appendix).

Results

Study population

The sample exceeded expectations: 452 people attempted the survey, of whom 393 (86.9%) completed all or parts of it. We excluded responses from those who did not complete the central study questions comparing experiences of and preferences between the two systems. The final analysis group had 310 participants.

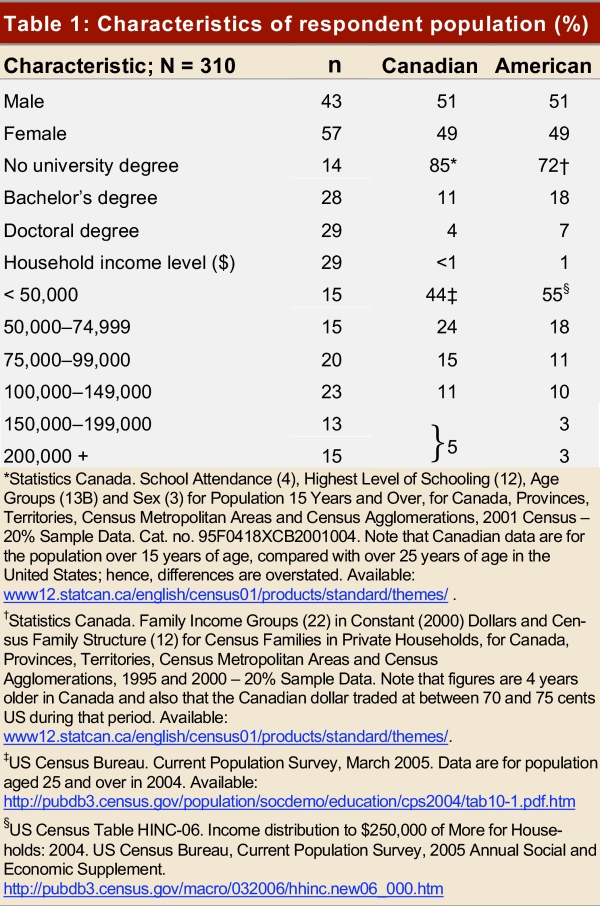

As expected, the respondents were much more highly educated and considerably better off financially than the general Canadian population (Table 1). However, they were more representative of émigrés to Canada (in 2002, 46% of immigrants from all countries had at least a university degree).11 Half of the respondents resided in Alberta (where 11% of the Canadian population live), 41% in British Columbia or Ontario (where, combined, 50% of the population live), and 8% were living elsewhere in Canada. One-fifth of the respondents were working in health care.

Table 1.

Characteristics of respondent population (%)

Health status and health care utilization

Respondents were healthy: 83% self-rated their health status as excellent or very good in the 2 years before moving to Canada, as compared with 73% of Canadians in the top income quintile who give their health this rating. Eighty percent rated the health status of their partner or spouse and 85% rated that of other household members as excellent or very good. Thirty-one percent reported that, since moving to Canada, at least one member of their household had experienced a chronic illness; 21% of respondents had had surgery in a hospital requiring an overnight stay; and 25% had had day surgery procedures. The typical household had made 5 visits to a family doctor, 2 to a specialist, and 1 to an emergency department and had filled 4 drug prescriptions annually. Thirty percent had received health care of any type in the United States in the previous year, and 11% had travelled to the United States expressly for that purpose.

Insurance coverage and out-of-pocket costs

Not surprisingly, given their income and education, 98% of respondents had health insurance before their arrival in Canada, mostly through employer-paid, for-profit insurance plans. Ninety-one percent had health insurance supplementary to the main plan. These data are significant: the study respondents by and large experienced the best of the US health care system, which very likely influenced their expectations and assessment of the Canadian system. Seventy-two percent were very or somewhat satisfied with their US health insurance overall, whereas 19% were somewhat or very dissatisfied.

Interestingly, given their socioeconomic status, 32% reported that health care coverage had exerted quite a lot or a great deal of influence on where they looked for a job in the United States, and 29% reported that this consideration influenced decisions about whether to stay in or leave a job. In addition, 24% reported paying out-of-pocket health care costs in the United States that created significant financial hardship, compared with 5% who reported a similar experience in Canada.

Expectations of Canadian health care before arrival

Two-thirds of respondents had formed an opinion of Canadian health care before their arrival. Of these, 35% had anticipated that the system would be worse than what they were used to in the United States, 29% had thought it would be better, and 37% had thought it would be the same. One-quarter indicated that their opinion had some influence on their decision to move to Canada, and 95% of these said it had been a positive motivator.

Comparative assessment of experiences in the two systems

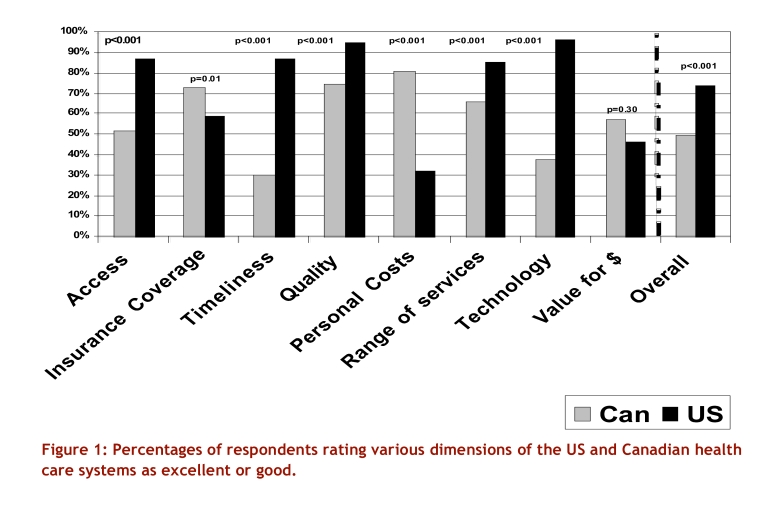

Figure 1 reports respondents' assessments of the timeliness and quality of Canadian and US health care services, based on their own experiences. By considerable margins, respondents rated the US system as better than the Canadian system in all categories except the cost of drugs and administrative complexity. The gaps were larger for timeliness than for quality-of-care items. Notably, 41% rated the United States as providing greater freedom to choose health care providers, compared with 27% who rated Canada higher in this regard.

Figure 1.

Percentages of respondents rating various dimensions of the US and Canadian health care systems as excellent or good

Comparative assessment of the merits of the two systems

Figure 1 also reports ratings of a number of structural aspects of the two systems. By and large, these reflect the ratings of the care itself, although the views on the system as a whole are somewhat more generous toward Canada. Respondents were particularly critical of the timeliness and availability of specialized services in Canada. Canada was rated considerably better only with respect to out-of-pocket costs, and somewhat better on the question of cost relative to quality. Overall, 50% rated the Canadian system as good or excellent, compared with 74% who gave this rating to the US system.

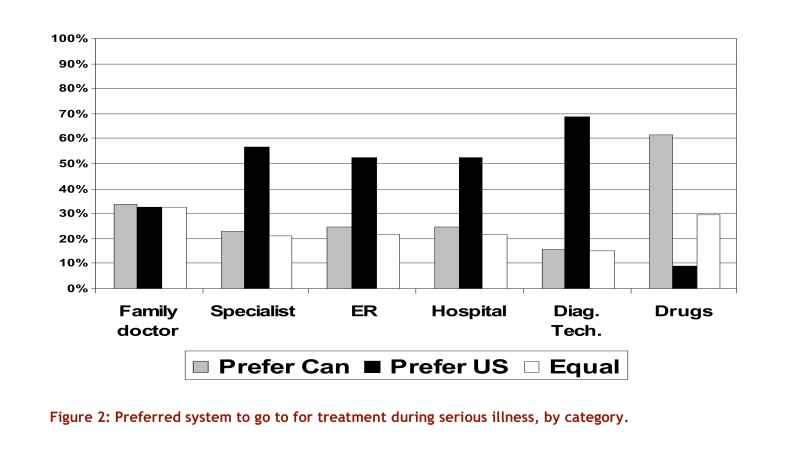

Similarly, we asked respondents to indicate where they would prefer to obtain treatment if they or a household member became seriously ill. Figure 2 shows that most preferred US care in 4 of 6 categories and Canadian care in 1 category (prescription drugs); preference for care provided by a family physician was distributed equally between the two countries.

Figure 2.

Preferred system to go to for treatment during serious illness, by category

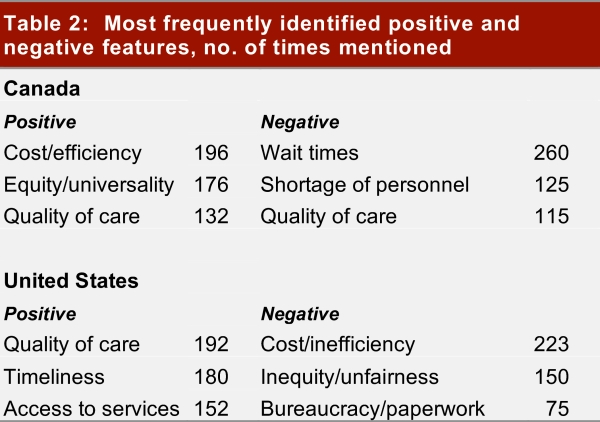

We asked respondents to list the 3 most positive and negative aspects of both health care systems. Table 2 lists the most commonly mentioned responses. Quality, comprehensiveness and accessibility of care appeared in roughly equal numbers as perceived "positives" and "negatives" in the Canadian system. Equity/universality of coverage was considered a major positive in Canada and a major weakness in the United States. Cost/efficiency was considered a major positive in Canada and a major negative in the United States, whereas wait times were perceived as the principal Canadian negative and their absence a major US positive.

Table 2.

Most frequently identified positive and negative features, no. of times mentioned

Differences in opinion attributable to length of time in Canada and place of residence in Canada

Our study included roughly equal numbers of Americans who had moved to Canada in 2000 or later, or before 2000. Ratings and opinions generally did not vary according to how long respondents had lived in Canada. However, 39% of the earlier arrivals had anticipated that health care would be better in Canada than in the United States, as compared with 26% of more recent arrivals (p = 0.02). Among the later arrivals, only 15% rated the quality of care provided by Canadian family physicians as better than in the United States, whereas 41% rated it worse; among earlier arrivals 29% rated family medicine as better and 24% rated it as worse (p < 0.01).

For almost all measures, province of residence in Canada did not influence perceptions. Albertans were moderately more positive about the quality of care than their counterparts in other provinces, and Albertans and Ontarians rated the efficiency of their provinces' services somewhat higher.

Qualitative comments on overall system comparisons

Respondents rated the Canadian system as a whole more highly than its component parts. They often tempered their praise for the US system with caveats such as, "If you're rich, you can get state-of-the-art care," or, "All positive features are contingent on having good private health insurance." They also identified equity or universality as a major strength in Canada, even though they had not been personally disadvantaged in the less equitable American system.

These reservations are reflected in the responses to the question, "All things considered, which system do you prefer?" Here the margin was narrow: 45% chose the US system, and 40% chose Canada's.

Discussion

A novel method to survey a hard-to-reach, important population has yielded new insights into the comparative performance of two health care systems. Americans of high socio-economic status who have used both the Canadian and the US health care systems generally perceive the timeliness, availability and quality of care to be better in the United States. However, they recognize that the US system is both costly and inaccessible to many and, taking all factors into consideration, respondents are evenly divided about which system they prefer.

This study adds to the literature in two important ways. First, it establishes that head-to-head comparisons of health care systems are possible using relatively inexpensive methods, even where standard population sampling is not possible. Second, it reveals that people's views of the overall quality of a health care system are not purely a function of their own care experiences. For many American émigrés of high socio-economic status, the universality, equity and efficiency of the Canadian system more than offsets concerns about the timeliness and availability of care. For others, it does not. Regardless, it seems clear that in rating a health care system, people take into account more than their own circumstances and experiences, and ask questions beyond "What has it done for me lately?"

Although respondents to our survey constitute an unusual demographic group, their assessment of the Canadian system is remarkably similar to that of Canadians in general. A 2003 Canada-wide Pollara Inc. survey12 asked about timeliness, range and comprehensiveness, and quality of care. The results were similar to those obtained in our survey, except that 30% of our respondents rated timeliness of care in Canada as excellent or good, while 43% of the Pollara respondents said they were very or somewhat satisfied in this regard.

Study limitations

Study participants were self-selected; we cannot know whether their views are representative of those of non-participants. As noted, respondents' socio-economic status was very high, and their perceptions cannot be assumed to reflect what the "typical" American might think of either system. Alberta, and the city of Calgary in particular, is overrepresented in the study population, although location only rarely affected the results, and then only modestly.

Conclusions

Highly educated, prosperous American émigrés to Canada are comparatively unimpressed with many elements of the Canadian health care system, but are more generously disposed toward its fairness and efficiency. Respondents' opinions of the quality and timeliness of care in Canada are similar to those of Canadians in general. In this sense, the study findings challenge two prevailing ideas: that Canadians idolize their universal-coverage medicare program to the point of being wilfully blind to its flaws, and that Americans who are accustomed to the best of US health care would be categorically harsh critics of the Canadian system and unsympathetic to its egalitarian ethos. These findings may be of interest to policy-makers not only in Canada and the United States but also internationally as all countries struggle to improve quality, contain costs, and allocate resources among competing interests.

Contributors

Steven Lewis conceived the study. Lewis, William Ghali, Colleen Maxwell, James Dunn and Tom Noseworthy developed and refined the methods. Danielle Southern posted the survey, gathered and analyzed the data, and prepared the quantitative data tables. Lewis analyzed the qualitative data. Lewis drafted the manuscript. All reviewed and contributed revisions to drafts and approved the final version for submission. Fatima Chatur staffed the toll-free access line and handled all inquiries. Steven Lewis is the corresponding author and guarantor.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karen Thomas, Gail Corbett, and Rhonda Watson of the Communications and Fund Development Office, Faculty of Medicine, University of Calgary, for organizing our media events and releases and their support and advice on publicizing the study. We are grateful to the Max Bell Foundation, which funded the study. We also thank Ms. Becky Shaw and Ms. Ashley Halsey, Americans residing in Canada who participated in the media events that informed the public of our study. Dr. Ghali is supported by a Government of Canada Research Chair in Health Services Research. Drs. Ghali and Maxwell are supported by Health Scholar Awards from the Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. Drs. Maxwell and Dunn are supported by New Investigator Awards from the Canadian Institute of Health Research.

Biographies

Steven Lewis, MA, President of Access Consulting, Ltd., Saskatoon, Sask., and Adjunct Professor, Centre for Health and Policy Studies and the Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary, is a health policy analyst, researcher and commentator.

Danielle A. Southern, MSc, is a Research Associate with the Centre for Health and Policy Studies and the Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary.

Colleen J. Maxwell, PhD, is an Associate Professor in the Departments of Community Health Sciences (Centre for Health and Policy Studies) and Medicine working in the areas of aging, pharmacoepidemiology and health services research.

James R. Dunn, PhD, is a Research Scientist at the Centre for Research on Inner City Health, The Keenan Research Centre in the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute of St. Michael's Hospital, and an Associate Professor of Geography and Public Health Sciences at the University of Toronto.

Tom W. Noseworthy, MD, MSc, MPH, is the Director of the Centre for Health and Policy Studies and Head of the Department of Community Health Sciences, University of Calgary.

William A. Ghali, MD, MPH, is a Professor in the Departments of Medicine and Community Health Sciences at the University of Calgary.

Appendix 1.

Qualitative results

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

Funding Source: Max Bell Foundation.

References

- 1.Hayward R A, Kravitz R L, Shapiro M F. The U.S. and Canadian health care systems: views of resident physicians. Ann Intern Med. 1991 Aug 15;115(4):308–314. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-115-4-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blendon RJ, Schoen C, DesRoches C. Common concerns amid diverse systems: health care experiences in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2003;22(3):106–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blendon RJ, Schoen C, DesRoches C. Inequities in health care: a five-country survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 2002;21(3):182–91. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.3.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donelan K, Blendon RJ, Schoen C. The elderly in five nations: the importance of universal coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2000;19(3):226–35. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.19.3.226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donelan K, Blendon RJ, Schoen C. The cost of health system change: public discontent in five nations. Health Aff (Millwood) 1999;18(3):206–16. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.3.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiken LH, Clarke SP, Sloane DM. Nurses' reports on hospital care in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2001;20(3):43–53. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.3.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schoenfeld E R, Greene J M, Wu S Y, O'Leary E, Forte F, Leske M C. Recruiting participants for community-based research: the Diabetic Retinopathy Awareness Program. Ann Epidemiol. 2000 Oct;10(7):432–440. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00067-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Faugier J, Sargeant M. Sampling hard to reach populations. J Adv Nurs. 1997 Oct;26(4):790–797. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnold A, Johnstone B, Stoskopf B, Skingley P, Browman G, Levine M, Hryniuk W. Recruitment for an efficacy study in chemoprevention--the Concerned Smoker Study. Prev Med. 1989 Sep;18(5):700–710. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(89)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Statistics Canada Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census01/products/standard/themes/ListProducts.cfm?Temporal=2001&APATH=3&Theme=43&FREE=0.

- 11.Canadian Labour and Business Centre . Immigration and skill shortages handbook. http://www.clbc.ca/files/Reports/Immigration_Handbook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pollara Inc. Health care in Canada survey retrospective 1998–2003. 2003. http://www.mediresource.com/e/pages/hcc_survey/pdf/HCiC_1998-2003_retro.pdf.