Abstract

Dengue virus (DENV) is listed as one of the NIAID Category A priority pathogens. Dengue disease is endemic in most tropical countries, with an estimated 2.5 billion people living in areas at risk of DENV infection. Due to the lack of vaccines and antiviral drugs, it is now a huge public health burden around the world. In order to screen large compound libraries for the identification of novel antivirals targeting DENV, it is essential to develop a high throughput screening (HTS) amenable assay. Here, we present the development, optimization and validation of a cytopathic effect-based assay against Dengue virus serotype-2 (DENV-2). The assay conditions, including cell culturing conditions, DMSO tolerance and the multiplicity of infection, were optimized in both 96- and 384-well plates. Assay robustness and reproducibility were determined under the optimized conditions in 96-well plate, including Z'-value of 0.71, signal-to-background ratio of 6.88, coefficient of variation of 6.3% in mock-infected cells and 12.3% in DENV-2 infected cells. This assay was further miniaturized into a 384-well plate format with similar assay robustness and reproducibility comparing with these in the 96-well plate format. This assay was then validated using the LOPAC1280 compound library, demonstrating its repeatability with comparable assay robustness and reproducibility. This fully developed and validated HTS amenable assay could be used in future studies to screen large compound libraries for the identification of novel antivirals against dengue disease.

Keywords: Dengue virus, high throughput screening, HTS, cytopathic effect, CPE, assay development, assay optimization, assay validation, antiviral

Introduction

Dengue disease is an arthropod-borne disease and Dengue virus (DENV), including serotypes -1, -2 -3, and -4, is transmitted from person to person by Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus mosquitoes in the domestic environment [1]. Recently, dengue disease became the most important mosquito-borne viral disease affecting human, and is endemic in most tropical countries of the South Pacific, Asia, the Caribbean, the Americas and Africa [2–4]. More than 2.5 billion people are now living in areas at risk of DENV infection. The recent trend of increased epidemic dengue activity and increased incidence of Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF) around the world is unprecedented [5, 6]. In 2008, there were 908,926 reported cases, 58,521 laboratory confirmed cases and 306 deaths in the Americas only; including a Brazilian national total of 734,384 reported cases, 9,957 DHF cases and 212 deaths [7].

With the rapid expansion of dengue disease in most tropical and subtropical areas of the world, it is urgent to develop effective prevention and control measures, including antivirals against dengue disease. A number of antiviral compounds, including ribavirin, mycophenolic acid, 7-deaza-2'-C-methyl-adenosine, and 6-O-butanoyl castanospermine, have shown their efficacy in inhibiting DENV replication in vitro [8–13]. Nevertheless, there are still no antiviral drugs being tested against dengue disease in any clinical trials.

An antiviral drug must be validated in the in vitro cytopathic effect (CPE)-based assay, which allows the evaluation of antiviral efficacy against the entire dengue viral life-cycle. The CPE-based assay is one of the most reliable and robust assays for the screening of large compound libraries, and has been successfully adapted into high throughput format in several recently concluded HTS campaigns for the identification of novel antivirals against influenza virus [14, 15], severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) [16], arenaviruses [17] and Bluetongue virus [18]. Although DENV infection does induce CPE in various cell culture system, including HeLa and hepatoma cells [19, 20], there was no CPE-based, HTS amenable assay available against DENV, due to technical hurdles such as the difficulties in quantitating CPE, optimizing multiplicity of infection (MOI) for CPE induction, low signal-to-background (S/B) ratio and low Z'-value. Thus, there is very little success in using the CPE-based assay against DENV as a HTS assay to screen large compound libraries, which further hampered the antiviral drug discovery. Here, we present the development, optimization and validation of a HTS amenable, robust and reproducible CPE-based assay against serotype 2 dengue virus (DENV-2).

Methods and materials

Cell culture

BSR cells, a derivative cell line from baby hamster kidney (BHK) cells, and LLC-MK2 cells, a monkey kidney cell line, were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, GIBCO) containing 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Invitrogen) and 100U/ml penicillin-streptomycin (P/S) (Invitrogen). Cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5.0% CO2 and 80-95% humidity. Once grown to 100% confluency, cells were washed once with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), trypsinized (TryLEM Express, GIBCO), and re-suspended in fresh media. For all the experiments carried out in this paper, unless otherwise noted, cells were harvested and re-suspended in assay medium: DMEM supplemented with 100 µg/ml streptomycin, 100 IU Penicillin/L and 1% FBS.

DENV-2 culture

Dengue virus serotype-2 (DENV-2), strain New Guinea C, was obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Catalog number VR-1584, Manassas, VA, USA), which has been adapted to LLC-MK2 cells. To propagate DENV-2, LLC-MK2 cells were grown in 75 cm2 flasks to 90% confluency, and infected with DENV-2 at MOI of 0.1. After 144 h incubation, cells and supernatant were harvested and centrifuged at 2,000 X rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The cell pellet was re-suspended in 5 ml fresh media, sonicated, and centrifuged at 3,000 X rpm for 10 minutes at 4°C. The supernatants were collected, combined, aliquoted and stored at −80°C as DENV-2 stock virus. The DENV-2 stock virus was titrated in BSR cells using the 50% tissue culture infectious dose (TCID50) assay. The final titer was determined at 5.0 X 105 TCID50/ml.

TCID50 assay and virus titer determination

Virus titers were determined in BSR cell monolayer grown in 96- well plates. BSR cells were seeded at 5,000 cells/well, and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 80-95% humidity. A volume of 100 µl of 10-fold serially diluted virus was inoculated into each well in quadruplicate format. Plates were further incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 80-95% humidity for 120 h, after which, CPE was observed microscopically at 40 X magnification. Virus titers were expressed as TCID50 units per ml.

Cell plating

Cells were seeded in black 96- and/or 384-well plate with clear flat bottom (Corning). For assay optimization, cells were plated in 96-well plates at a cell density of 5,000 cells/well (or otherwise noted) in 80 µl assay media using a MicroFlo Select dispenser (BioTek Instruments, Inc.). When miniaturized into 384-well plates for the validation assay, cells were seeded at 1,500 cells/well (or otherwise noted) in 15 µl assay media using the BioTek MicroFlo Select dispenser. Plated cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5.0% CO2 and 80-95% humidity for 2 h prior to the addition of virus and/or compounds.

Virus addition

Cells were infected with DENV-2 at MOI of 0.4 (or otherwise noted). The DENV-2 stock virus at 5 X 105 TCID50/ml was diluted in assay media and then added to the compound-treated wells and the virus only control wells. Cells were also mock infected by adding assay media as mock infection control wells. All additions were carried out using the BioTek MicroFlo Select dispenser (BioTek Instruments, Inc.) housed in a class II Biosafety Cabinet within the Bio-Safety Level 2 laboratory. Plates were incubated for another 120 h, at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 80-95% humidity. The final total volume was 25 µl/well for 384-well plates and 100 µl/well for 96-well plates.

Luminescent signal detection and endpoint reading

CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay kit (Promega Inc., Madison, USA) was used to determine the cell viability in vitro. The CellTiter-Glo buffer and the lyophilized CellTiter-Glo substrate were thawed and equilibrated to room temperature prior to use. The homogeneous CellTiter-Glo reagent solution was reconstituted after mixing the lyophilized enzyme/substrate and the reagent buffer according to the manufacturer's instructions. Meanwhile, the assay plates were also equilibrated to room temperature for 15 minutes. An equal volume of CellTiter-Glo reagent, 25 µl for 384-well plate and 100 µl for 96-well plate, was added to each well robotically. Plates were further incubated for 15 min at room temperature to stabilize luminescent signals. Units of luminescent signal generated by a thermo-stable luciferase are proportional to the amount of ATP presented in viable cells. Luminescence was measured using a BioTek synergy 2 multi-label reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc.) with an integration time of 0.1 s/well.

Compound preparation for the screening of the small compound library

LOPAC1280 (Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was originally purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and stored in DMSO at 2 mM per compound in 96-well plates at −20°C. Before loading, all compound plates were equilibrated to room temperature, and each compound plate was diluted in assay media in a well-to-well manner. The dilution plates were stored in 4°C before transferring to 384-well plates. Four 96-well dilution plates were transferred into one 384-well plate in a well-to-well manner. The final concentration for each compound was 10 µM in 384-well plates. Compounds diluting and compounds transferring were all operated by PrecisionTM Automated Microplate Pipetting Systems (BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

Validation of 384-well format assay

The LOPAC1280 was screened in duplicate using the optimized in vitro CPE-based assay on a HTS platform using the luminescent-based CellTiter-Glo reagent (Promega). Briefly, cells were plated 15µl/well at a cell density of 1,500 cells/well in black 384-well plates with clear-bottom (Corning) using BioTek MicroFlo Select dispenser. Plates were then incubated for 2 h at 37°C, 5.0% CO2 and 80-95% humidity. A total of 10 µl diluted compounds were dispensed to each well in the assay plates by the BioTek PrecisionTM Automated Microplate Pipetting Systems. The compound wells and the virus control wells were infected with DENV-2 at MOI of 0.4. Mock infected cells were added with 10µl assay media. Under the optimized assay conditions, the final assay volume in each well was 25 µl, the final concentration of each testing compound was 10 µM. All experiments were carried out in a class II Biosafety Cabinet within the Bio-Safety Level 2 laboratory. All plates were incubated for another 120 h, at 37°C, 5.0% CO2 and 80-95% humidity.

Data analysis

For the validation assay, each assay plate contains two columns of control wells with mock infected cells, and two columns of control wells with cells infected with DENV-2. All control wells were treated with DMSO at same concentration as assay wells and used to calculate Z'-value for each plate and to normalize the data on a per plate basis. All raw data were analyzed for the determination of Z'-value, S/B ratio and percent inhibition for each assayed compounds. Results were expressed as percent inhibition of CPE where 100% inhibition of CPE was equal to the mean of the mock infected cell controls, and 0% of inhibition was equal to the mean of the DENV-2 infected cell controls. Statistical calculations of Z'-values were made as follows:

Z' = 1–((3StdDevSü3 StdDevB)/|MeanS – MeanB|)

Here MeanS is the mean luminescent signals from mock infected cell controls, StdDevS is the standard deviation of the luminescent signals from mock infected cell controls, MeanB is the mean luminescent signals from DENV-2 infection controls, and StdDevB is the standard deviation of the luminescent signals from virus infection controls. Coefficient of ariation (CV) = StdDev/Mean and S/B = MeanS/MeanB [21, 22].

Results

Quantitation of CPE induced post DENV-2 infection

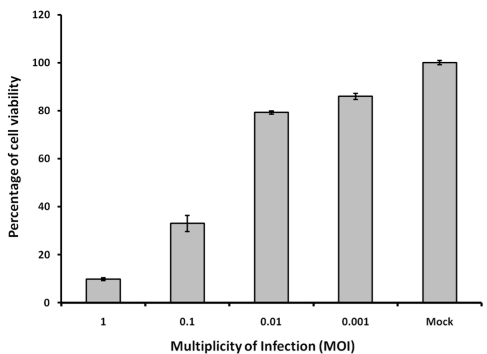

The induction of CPE post DENV infection is observable in various cell lines, including HeLa and hepatoma cells [19, 20]. In this assay system, CPE could also be observed in BSR cells at different hours post infection (h.p.i.) of DENV-2, depending on the MOI. In order to develop a HTS amenable assay for antiviral drug screening against DENV, it is critical that the CPE induced post DENV-2 infection can be quantitated in 96-well plates or higher format with a simple assay protocol such as “mix and measure”. The quantitation of CPE induced post DENV-2 infection in BSR cells was developed using the CellTiter-Glo luminescent cell viability reagent (Promega), a homogeneous method of determining the number of viable cells in culture based on the quantitation of ATP present, which signals the presence of metabolically active cells. Cell viability in BSR cells post DENV-2 infected was compared to the cell viability in mock infected cells at 120 h.p.i., with 1.2-, 1.3-, 3.0- and 10.2-fold decreases of cell viability, i.e. S/B ratios, at MOI of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1 and 1, respectively (Figure 1). This result demonstrated that DENV-2 induced CPE can be quantitated in this assay system using BSR cells. Cells infected with higher MOIs showed fairly higher signal difference window or S/B ratio indicating the correlation between CPE and luminescent signals in cells infected with DENV-2.

Figure 1.

Quantitation of CPEs induced in BSR cells post DENV-2 infection. BSR cells were seeded at 5,000 cells/well and then infected with DENV-2 at different MOIs as indicated. Inhibitions of cell viability were determined using the CellTiter-Glo reagent at 120 h.p.i.. Mock infection: BSR cells were mock-infected by adding DMEM media only. MOI: Multiplicity of Infection. Each data point represents the average value of 8 replicates.

Assay condition optimization

It is commonly observed that CPE can be induced within 72 h post RNA virus infection, including the induction of CPE by BTV [18] and SARS-CoV [16]. Comparing with these systems, quantitatable induction of CPE post DENV-2 infection takes longer period, usually more than 120 h. The lengthy period of culturing BSR cells makes the assay condition optimization challenging. We took a step-by-step approach to determine the optimal assay conditions, including seeding cell density, end-point determination, FBS concentration, cell tolerance to DMSO and MOI as described below.

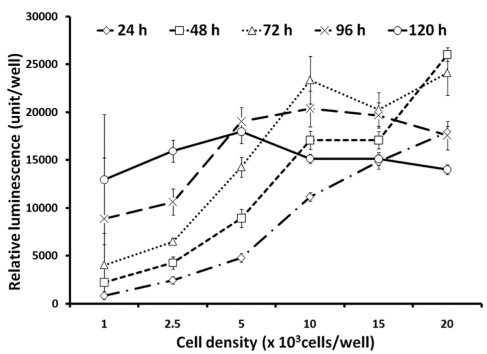

Optimization of seeding cell density

Since reasonably higher S/B ratios were observed at 120 h post DENV-2 infection, the optimization of seeding cell density will be critical in order to obtain high luminescent signals without triggering cell overgrowth up to 120 h post seeding. To determine the maximum seeding cell density, cells were plated at densities ranging from 1,000 up to 20,000 cells/well in 96-well plates using assay media, and cultured up to 120 h. Luminescent signals representing cell viabilities were determined at 24 h intervals over the 120 h period using CellTiter-Glo reagent (Figure 2). At cell densities of 1,000 and 2,500 cells/wells, BSR cells continued to grow till 120 h post seeding with no signs of cell overgrowth. At 5,000 cells/well, cell growth reached a plateau at 96 h post seeding and luminescent signals decreased slightly at 120 h post seeding. At 10,000, 15,000 and 20,000 cells/well, substantial decreases of luminescent signal indicated cell overgrowth within 72 h culturing. Since luminescent signals were higher at 5,000 cells/well when compared with the signal from 1,000 and 2,500 cells/well, we chose the cell density of 5,000 cells/well as the cell density for further optimization considering the slight signal decrease that might be related with cell overgrowth.

Figure 2.

Optimization of seeding cell density. BSR cells were seeded at different cell densities in 96-well plates. Cell viabilities were measured at different times post seeding and were expressed as relative luminescent signal units per well using CellTiter-Glo reagent. Each data point represents the average value of 8 replicates.

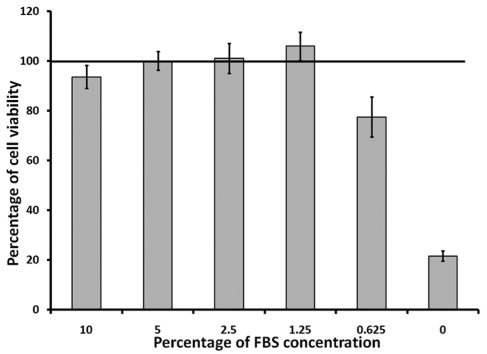

Determination of optimal FBS concentration

In the previous experiment, we showed that when cells were seeded at 5,000 cells/well with 1% FBS in the media, the luminescent signals decreased slightly at 120 h post seeding. Thus, we further optimized the FBS concentration in the media with five designated FBS concentrations, ranging from 0% up to 10%. Cell viabilities were evaluated at 72 h, 96 h and 120 h. Comparing with the previous result at 1% FBS (Figure 2), we showed that cells were still growing actively with no sign of overgrowth at 1.25% FBS at 120 h.p.i. (Figure 3). Thus, we selected 1.25% FBS as the optimal FBS concentration for all subsequent experiments.

Figure 3.

Effect of FBS in DMEM media on the growth of BSR cells. BSR cells were seeded at 5,000 cells/well in 96-well plates with DMEM containing different concentration of FBS and incubated at 37 °C with 5.0% CO2. Cell viability were determined at 120 h post seeding using CellTiter-Glo reagent. Line indicated the level of luminescent signals from cells at regular maintenance media containing 5% FBS, which was pre-set as 100%. Each data point represents the average value of 8 replicates.

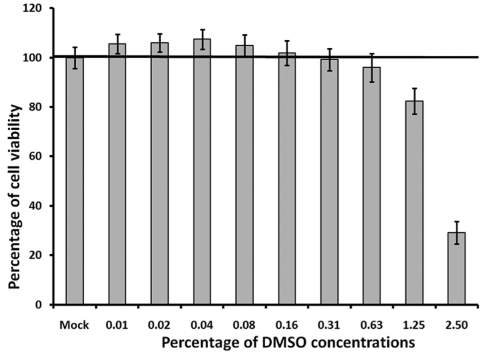

Effect of DMSO on cell viability in BSR cells

During the small-molecule chemical compound library screening, all original testing compounds were delivered at fixed concentrations in 100% DMSO. Thus, DMSO solvent compatibility of the assay needed to be determined to evaluate the effect of DMSO on cell growth and cell viability over the 120 h period. After being seeded in 96-well plates at 5,000 cells/well and 1.25% FBS, BSR cells were treated with DMSO at concentrations ranging from 0.01% up to 2.5% (Figure 4). Cell viability was determined using the CellTiter-Glo reagent after 120 h of incubation. The effect of DMSO on cell viability was evaluated by comparing the cell viability in DMSO treated cells to cell viability in cells that were not treated with DMSO, i.e. the mock treated cells with 100% pre-set viability. When BSR cells were treated with DMSO concentrations less than 1.25%, no decreases in the cell viability were observed. In contrast, there was a slight increase of cell viability, although not substantial, when cells were treated with DMSO concentration below 0.16%. However, when cells were treated with concentrations of DMSO over 1.25%, a notable decrease of cell viability was observed comparing to the cell viability in mock treated cells (Figure 4). This result suggests that the DMSO concentration should be kept between 0.16% and 0.625% for antiviral drug screening using this assay, and there should be no more than 1.25% DMSO in the culture for the entire screening. This result is coincident with most standard cell based assays recommending that the final DMSO concentration should be kept under 1%.

Figure 4.

Evaluation of the DMSO tolerance in BSR cells. BSR cells were seeded at 5,000 cells/well with DMEM containing 1% FBS. The assay media also contain different concentrations of DMSO. Percentages of cell viability were determined using CellTiter-Glo reagent at 120 h post seeding. Line indicated the level of luminescent signals from cells without DMSO treatment, which set as 100%. Each data point represents the average value of 8 replicates.

Optimization of MOI

DENV infection in Vero cells can induce both necrosis at a higher infectious dose (MOI ≥ 10) and apoptosis at a lower MOI (<10) [23]. Although both necrosis and apoptosis will generate observable CPE, it is important to note that the cytotoxic effect resulting from the accumulating DENV particles in the cells should be avoided for antiviral drug screening. Thus, we chose to use MOI <10 for this MOI optimization assay.

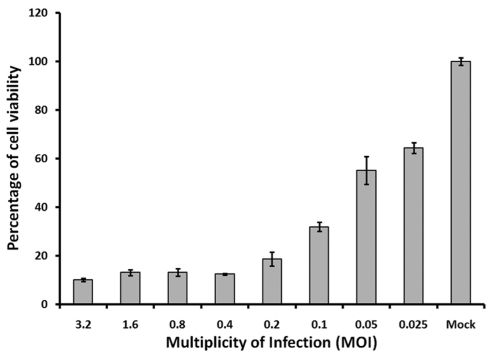

Because the extent of DENV-2 induced CPE is affected by the initial infectious dose, DENV-2 MOI was optimized to achieve the relatively lower luminescent signals at the lowest DENV-2 MOI. As shown earlier, the luminescent signals were decreased 3.0- and 10.0- fold at MOIs of 0.1 and 1, respectively (Figure 1). For further optimization, we chose eight MOIs, ranging from 0.025 to 3.2, to infect BSR cells at the optimal conditions. Cell viability was evaluated using the CellTiter-Glo reagent. At 120 h.p.i, the differences of luminescent signals (i.e. S/B ratios) between mock infected cells and DENV-2 infected cells were 1.6, 1.8, 3.1, 5.4, 8.0, 7.6, 7.6 and 10.0 folds at MOI of 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.4, 0.8, 1.6, and 3.2, respectively (Figure 5). The S/B ratio at MOI of 0.4 was the lowest MOI with comparable low cell viability and comparable high S/B ratio (8.0) to that of MOI 0.8, 1.6 and 3.2, which fits our standard to achieve relative high signal difference window with lowest MOI. Thus, MOI of 0.4 was selected for further analysis including the determination of assay robustness.

Figure 5.

Optimization of DENV-2 MOI for the induction of CPE in BSR cells. BSR cells were seeded at 5,000 cells/well, and then infected by different DENV-2 at different MOIs. Percentages of cell viabilities were determined using luminescent signals from CellTiter-Glo reagent at 120h post seeding. Each data point represents the average value of 8 replicates.

Assay robustness determination

Various assay parameters, including Z'-value, CV and S/B ratio, provide an indication of the assay reliability during normal run conditions and determines the assay robustness and reproducibility. The Z'-value evaluates the assay's signal dynamic range, the data variation associated with the sample measurement, and the data variation associated with the reference control measurement. The S/B ratio between the mean maximal signal and the mean minimum signal or background signal, describes the dynamic range of the assay. CV is a normalized measure of dispersion of a probability distribution defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean. To determine the Z'-value, CV and S/B ratio, the CPE-based assay in 96-well plates was run at the optimized conditions including cell density at 5,000 cells/well and 1.25% FBS, DENV-2 infection at MOI of 0.4 and final luminescence signals read at 120 h.p.i. The 96-well plate was divided into four quadrants, with the mock infected cell controls in Quadrant I and IV as positive controls, and the DENV-2 infected cells as negative controls in Quadrant II and III on the plate. The Z'-value analysis was performed repeatedly to demonstrate reproducibility. We obtained a Z'-value of 0.71, an S/B ratio of 6.88, and CV of 6.3% for mock infected cells and 12.3% for DENV-2 infected cells under the optimized assay conditions using the formula described earlier [22]. This result demonstrated the successful adaptation of the CPE-based assay against DENV-2. This assay was therefore suitable for current use, or for further development into a primary HTS assay.

Miniaturization of the assay into 384-well plates

Since HTS involves the use of robotic instrumentation capable of dispensing small volumes of compounds and buffers into microplates or other vessels, it is recommended to use 384-well plates or higher formats. The miniaturization of this CPE-based assay into 384-well plate format was carried out via the optimization of assay conditions for cell culture and DENV-2 infection to achieve the optimal conditions that yield the greatest dynamic range, that is, the greatest difference between infected and uninfected cells (S/B ratio > 5), with a Z'-value > 0.5 and a CV < 10%. Various assay conditions, including the determination of seeding cell density, optimization of cell culture conditions and MOI, were optimized similar to these experiments described for assay optimization in 96-well plates. The optimal experimental conditions were determined as seeding cell density at 1,500 cells/well, 1.25% FBS and MOI of 0.4, in 384-well plates. Under these optimal conditions, we obtained a Z'-value of 0.69, S/B ratio of 11.2, and CV of 7.1% in mock-infected cell control and 24.2% in DENV-2 infected cells.

Assay validation using LOPAC1280 compound library

The LOPAC1280 (Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) is designed for the validation of new drug discovery assays, and was used to validate the miniaturized antiviral assay against DENV-2. LOPAC1280 is a collection of high quality, innovative molecules that have been used for a broad range of researches including cell signaling and neuroscience, reflecting the most commonly screened targets in the drug discovery community.

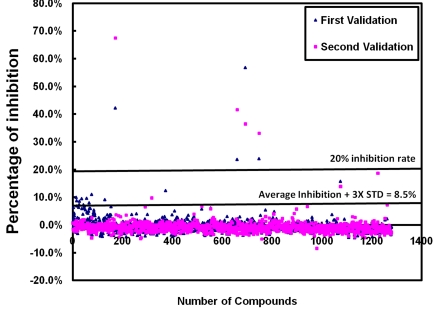

All compounds in the LOPAC1280 library was diluted in assay media to achieve a final concentration of 10 μM per compound per well. The compound library was screened in duplicate. Additional controls, including mock-infected cells with DMSO and DENV-2 infected cells, were added along the sides of the 384-well plate for quality control. The values from the mock-infected control wells were reviewed to determine the cell viability of each plate and pre-set as 100% inhibition, and the values of DENV-2 infected only cells were pre-determined as 0% inhibition. The values of cell viability for each compound were analyzed to determine the percentage of inhibition to DENV-2 induced CPE. Z'-values, S/B ratios, CVs for mock infected cells and DENV-2 infected cells were calculated and averaged from each plate. Based on the duplicated screening, we obtained an average Z'-value of 0.57 ± 0.05. The average CVs were 12% ± 2% in mock-infected cells and 19% ± 6% in DENV-2 infected cells. The average S/B ratio was 16.37 ± 3.66 for the entire screening. The percentage of inhibition of virus induced CPE from each compound in the screen was plotted in Figure 6. Effective “hit” compounds were defined as compounds displaying efficacy values greater than the mean of the negative control plus 3 times the standard deviation of the negative control mean, which was 8.5% in this duplicated screening. An arbitrary cut-off value of 20% inhibition rate for the entire screening was also applied. Out of the 1280 compounds screened, we identified 4 identical hits with over 20% CPE inhibition in both screenings.

Figure 6.

The percentage of inhibition to DENV-2 induced CPE from each compound in the validation assay using the LOPAC1280 compound library. Each dot represents one compound from the library, and total of 1280 compounds were plotted here. The lower line at 8.5% inhibition of virus induced CPE was calculated as the average inhibition plus three times standard deviation of % inhibition of all compounds from the entire screen. The higher line indicating the inhibition at 20% of DENV-2 induced CPE.

The reproducibility and robustness of the duplicate screens were demonstrated with similar Z' values (0.59 vs 0.55), CVs from both cell controls (11.76% vs 12.99%) and virus controls (23.63% vs 13.610%), and S/B ratios that averaged from each plate (19.00 vs 13.73) (Table 1). Overall, we observed an average hit rate of 0.55 - 1.02% and 0.31% for compounds that inhibited 8.5% and 20% of DENV-2 induced CPE, respectively. These results demonstrated that the assay was reproducible and robust for future HTS of large compound libraries.

Table 1.

Summary of the validation screening using LOPAC1280 against DENV-2

| N | Z' | CV(Cell) | CV(Virus) | S/B ratio | Number of hits | Hit rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Validation repeat 1 | 1280 | 0.59±0.02 | 11.76±0.22 | 23.63±11.06 | 19.00±0.88 | 13(>8.5%) | 1.02% |

| 4(>20%) | 0.31% | ||||||

| Validation repeat 2 | 1280 | 0.55±0.05 | 12.99±1.67 | 13.61±1.56 | 13.73±0.99 | 7(>8.5%) | 0.55% |

| 4(>20%) | 0.31% |

The CPE-based assay against DENV was validated twice using the LOPAC1280 compound library, via the screening of total 1280 compounds. Results from the validations screening assay were summarized and compared in the table. Number of hits and hit rates were expressed in two data sets. One set was expressed as the mean inhibition of CPE plus three times the standard deviation, which was 8.5% here. Another set was expressed as the 20% inhibition of the virus induced CPE. N: number of compound screened, Z': average Z'-value from each plate screened, CV: Coefficient of Variation, S/B ratio: signal-to-background ratio.

Discussion

The development of a HTS amenable assay is usually accompanied with rigorous standards that require specific attention to assay optimization. It is recommended that a simple “mix and measure” protocol be established to automate and validate specific cell-based assays for antiviral drug discovery. The determination of optimal culture conditions, the establishment of compound addition parameters and the validation of assay robustness are also required to achieve doable assay parameters, including Z'-value over 0.5, S/B over 5, and CV less than 10% [24]. For most antiviral HTS assay, it usually takes less than 72 h to observe a measurable CPE. However, the antiviral assay developed in this paper requires at least 120 h to detect the CPE-induced post DENV-2 infection. Such a lengthy assay period increases the challenge of optimizing assay conditions. Here, we present detailed, step-by-step method for optimizing assay conditions, which is critical for the success of the antiviral HTS assay development against Dengue disease. The assay robustness was established early in the assay development in 96-well plates, with Z'-value of 0.71, a S/B ratio of 6.88, CV of 6.3% in mock-infected cells and 12.3% in DENV-2 infected cells under the optimized assay conditions. This assay was miniaturized into 384-well plates with Z'-value of 0.69, S/B ratio of 11.2, and CV of 7.1% in mock infected cell control and 24.2% in DENV-2 infected cells under the optimized assay conditions. Further validation of the assay using the LOPAC1280 compound library showed an average Z'-value of 0.57 ± 0.05, average CVs of 12% ± 2% for mock infected cells and 19% ± 6% for DENV-2 infected cells. The average S/B ratio was 16.37 ± 3.66 for the entire screening. It is very common that CV was over 10% in virus infected cells as the cells react to virus infection differently with the addition of the compounds. Meanwhile, we also observed slight variation of the Z'-values, CVs and S/B ratios in different assay formats, which is very common for a HTS assay. When determining whether the assay is HTS amenable, it is important to obtain a high Z'-value, usually over 0.5. If the Z' value is between 0 and 0.5, the assay is considered doable but will require replicates during HTS. If the value is ≤ 0.5, the assay is considered excellent, and generally a single test of a compound library will be sufficient. Thus, the consistent Z'-value from the validation screenings, between 0.59 and 0.71, indicated that this assay was HTS amenable and robust for further screening of large compound libraries.

The assay repeatability or intra-assay precision was also determined with the repeated validation assay using the exact same LOPAC1280 compound library under the same optimized assay conditions at two separate but duplicated assays. We showed the two duplicated screenings with similar Z-values, S/B ratios and CVs in mock-infected cells and DENV-2 infected cells. The 8.5% inhibition of DENV-2 induced CPE equaled to average CPE inhibition plus three times standard deviation of % inhibition of all compounds from the duplicated screenings. We also applied an arbitrary cut-off value of 20% inhibition rate for the entire screening. Remarkably, we obtained four “hits” from the duplicated screening which were 100% identical for the 20% inhibition of DENV induced CPE. This further demonstrated that the assay was reproducible and reliable.

Several antiviral HTS assays have been developed for the drug discovery against dengue disease, including virtual screening [25], screening of small-molecule compound libraries using replicon-based assay [26–28], antisense RNA strategy development [29], and docking assay [30]. The replicon-based assay, using the replicon-harboring cell line, allows screening for inhibitors of viral replication, including translation, polyprotein processing, and minus- and plus-strand RNA synthesis [26, 27, 31, 32]. The antisense RNA strategies and virtual screening of small-molecule libraries also generate possible antivirals against dengue disease [25, 28]. While these assays showed certain advantages, it was believed that the standard CPE-based assay should be developed and validated to allow the evaluation of antiviral efficacy against the entire dengue viral life-cycle. The successful development, optimization and validation of the CPE-based assay against DENV into a HTS amenable, robust and reproducible assay, made it possible to screen large compound libraries to identify novel antiviral drugs against Dengue virus infection.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by NIH grants 7R03MH081271-02 and the impact funds from the University of Alabama at Birmingham to Q. LI. We thank Ms. Pegues for her critical reviewing of the manuscript and Mr. Wright for his technical supports.

References

- 1.Halstead SB. Dengue virus - Mosquito interactions. Annual Review of Entomology. 2008;53:273–291. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever. Fact sheet no. 117. 2002. [Accessed June 27, 2009]. 2009; Available at: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/index.html.

- 3.Ahmed J, Bouloy M, Ergonul O, Fooks A, Paweska J, Chevalier V, Drosten C, Moormann R, Tordo N, Vatansever Z, Calistri P, Estrada-Pena A, Mirazimi A, Unger H, Yin H, Seitzer U. International network for capacity building for the control of emerging viral vector-borne zoonotic diseases: ARBO-ZOONET. Euro Surveill. 2009;14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gubler DJ. The global emergence/resurgence of arboviral diseases as public health problems. Arch Med Res. 2002;33:330–342. doi: 10.1016/s0188-4409(02)00378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gould EA, Higgs S. Impact of climate change and other factors on emerging arbovirus diseases. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:109–121. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mairuhu AT, Wagenaar J, Brandjes DP, van Gorp EC. Dengue: an arthropod-borne disease of global importance. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;23:425–433. doi: 10.1007/s10096-004-1145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO/PAHO. 2008: Number of Reported Cases of Dengue & Dengue Hemorrhagic Fever (DHF), Region of the Americas (by country and subregion. Health Surveillance and Disease Prevention and Control / Communicable Diseases / Dengue 2009; Epidemiological Week / EW 53, data received 27 January 2009, Available at : http://www.paho.org/English/AD/DPC/CD/dengue-cases-2008.htm.

- 8.Courageot MP, Frenkiel MP, Dos Santos CD, Deubel V, Despres P. Alpha-glucosidase inhibitors reduce dengue virus production by affecting the initial steps of virion morphogenesis in the endoplasmic reticulum. J Virol. 2000;74:564–572. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.1.564-572.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diamond MS, Zachariah M, Harris E. Mycophenolic acid inhibits dengue virus infection by preventing replication of viral RNA. Virology. 2002;304:211–221. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takhampunya R, Padmanabhan R, Ubol S. Antiviral action of nitric oxide on dengue virus type 2 replication. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:3003–3011. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81880-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takhampunya R, Ubol S, Houng HS, Cameron CE, Padmanabhan R. Inhibition of dengue virus replication by mycophenolic acid and ribavirin. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1947–1952. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81655-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whitby K, Pierson TC, Geiss B, Lane K, Engle M, Zhou Y, Doms RW, Diamond MS. Castanospermine, a potent inhibitor of dengue virus infection in vitro and in vivo. J Virol. 2005;79:8698–8706. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8698-8706.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu S-F, Lee C-J, Liao C-L, Dwek RA, Zitzmann N, Lin Y-L. Antiviral effects of an iminosugar derivative on flavivirus infections. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:3596–3604. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.8.3596-3604.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Noah JW, Severson W, Noah DL, Rasmussen L, White EL, Jonsson CB. A cell-based luminescence assay is effective for high-throughput screening of potential influenza antivirals. Antiviral Res. 2007;73:50–59. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Severson WE, McDowell M, Ananthan S, Chung DH, Rasmussen L, Sosa MI, White EL, Noah J, Jonsson CB. High-throughput screening of a 100,000-compound library for inhibitors of influenza A virus (H3N2) J Biomol Screen. 2008;13:879–887. doi: 10.1177/1087057108323123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Severson WE, Shindo N, Sosa M, Fletcher T, 3rd, White EL, Ananthan S, Jonsson CB. Development and validation of a high-throughput screen for inhibitors of SARS CoV and its application in screening of a 100,000-compound library. J Biomol Screen. 2007;12:33–40. doi: 10.1177/1087057106296688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bolken TC, Laquerre S, Zhang Y, Bailey TR, Pevear DC, Kickner SS, Sperzel LE, Jones KF, Warren TK, Amanda Lund S, Kirkwood-Watts DL, King DS, Shurtleff AC, Guttieri MC, Deng Y, Bleam M, Hruby DE. Identification and characterization of potent small molecule inhibitor of hemorrhagic fever New World arenaviruses. Antiviral Res. 2006;69:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Q, Maddox C, Rasmussen L, Hobrath JV, White LE. Assay development and high-throughput antiviral drug screening against Bluetongue virus. Antiviral Res. 2009;83:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Buckley SM. Serial propagation of types 1, 2, 3 and 4 dengue virus in HeLa cells with concomitant cytopathic effect. Nature. 1961;192:778–779. doi: 10.1038/192778a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin Y-W, Wang K-J, Lei H-Y, Lin Y-S, Yeh T-M, Liu H-S, Liu C-C, Chen S-H. Virus replication and cytokine production in dengue virus-infected human B lymphocytes. Journal of Virology. 2002;76:12242–12249. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.23.12242-12249.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh RN, DeBiasio R, Hudson CC, Ramer ER, Cowan CL, Oakley RH. Quantitative cell-based high-content screening for vasopressin receptor agonists using transfluor technology. J Biomol Screen. 2005;10:476–484. doi: 10.1177/1087057105274896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang JH, Chung TD, Oldenburg KR. A Simple Statistical Parameter for Use in Evaluation and Validation of High Throughput Screening Assays. J Biomol Screen. 1999;4:67–73. doi: 10.1177/108705719900400206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Despres P, Frenkiel MP, Ceccaldi PE, Duarte Dos Santos C, Deubel V. Apoptosis in the mouse central nervous system in response to infection with mouse-neurovirulent dengue viruses. J Virol. 1998;72:823–829. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.823-829.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jonsson CB, White EL. Launching an HTS campaign to discover new antivirals. European Pharmaceutical Review. 2007:4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou Z, Khaliq M, Suk JE, Patkar C, Li L, Kuhn RJ, Post CB. Antiviral compounds discovered by virtual screening of small-molecule libraries against dengue virus E protein. ACS Chem Biol. 2008;3:765–775. doi: 10.1021/cb800176t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Puig-Basagoiti F, Deas TS, Ren P, Tilgner M, Ferguson DM, Shi PY. High-throughput assays using a luciferase-expressing replicon, virus-like particles, and full-length virus for West Nile virus drug discovery. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49:4980–4988. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.12.4980-4988.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puig-Basagoiti F, Tilgner M, Forshey BM, Philpott SM, Espina NG, Wentworth DE, Goebel SJ, Masters PS, Falgout B, Ren P, Ferguson DM, Shi PY. Triaryl pyrazoline compound inhibits flavivirus RNA replication. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50:1320–1329. doi: 10.1128/AAC.50.4.1320-1329.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray D, Shi P-Y. Recent advances in flavivirus antiviral drug discovery and vaccine development. Recent patents on anti-infective drug discovery. 2006;1:45–55. doi: 10.2174/157489106775244055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deas TS, Binduga-Gajewska I, Tilgner M, Ren P, Stein DA, Moulton HM, Iversen PL, Kauffman EB, Kramer LD, Shi PY. Inhibition of flavivirus infections by antisense oligomers specifically suppressing viral translation and RNA replication. J Virol. 2005;79:4599–4609. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.8.4599-4609.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Q-Y, Patel SJ, Vangrevelinghe E, Xu HY, Rao R, Jaber D, Schul W, Gu F, Heudi O, Ma NL, Poh MK, Phong WY, Keller TH, Jacoby E, Vasudevan SG. A small-molecule dengue virus entry inhibitor. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2009;53:1823–1831. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01148-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harvey TJ, Liu WJ, Wang XJ, Linedale R, Jacobs M, Davidson A, Le TT, Anraku I, Suhrbier A, Shi PY, Khromykh AA. Tetracycline-inducible packaging cell line for production of flavivirus replicon particles. J Virol. 2004;78:531–538. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.1.531-538.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu WJ, Chen HB, Wang XJ, Huang H, Khromykh AA. Analysis of adaptive mutations in Kunjin virus replicon RNA reveals a novel role for the flavivirus nonstructural protein NS2A in inhibition of beta interferon promoter-driven transcription. J Virol. 2004;78:12225–12235. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12225-12235.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]