Abstract

Background

Delay from onset of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) symptoms to hospital admission continues to be prolonged. To date community education campaigns on the topic have had disappointing results. Therefore, we conducted a clinical randomized trial to test whether an intervention tailored specifically for patients with ACS and delivered one-on-one would reduce pre-hospital delay time.

Methods and Results

Participants (N=3522) with documented coronary heart disease were randomized to experimental (n=1777) or control (n=1745) groups. Experimental patients received education and counseling about ACS symptoms and actions required. Patients were mean age 67±11 years and 68% were male. Over the two years of follow-up, 565 patients (16.0%) were admitted to an emergency department with ACS symptoms a total of 842 times. Neither median prehospital delay time (experimental 2.20 vs. control 2.25 hours) nor emergency medical system use (experimental 63.6% vs. control 66.9%) was different between groups, although experimental patients were more likely than control to call the emergency medical system if the symptoms occurred within the first 6 months following the intervention (p=0.036). Experimental patients were significantly more likely to take aspirin following symptom onset than control patients (experimental 22.3% vs. control 10.1%, p=0.02). The intervention did not result in an increase in emergency department utilization (experimental 14.6% vs. control 17.5%)

Conclusions

The education and counseling intervention did not lead to reduced pre-hospital delay or increased ambulance use. Reducing the time from onset of acute coronary syndrome symptoms to arrival at the hospital continues to be a significant public health challenge.

Individuals who experience the signs and symptoms of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) often delay seeking treatment.1,2 Unfortunately, a delay of only a few hours can have a significant impact on patient survival,3 with a 30 minute delay reducing average life expectancy by 1 year.4 In recognition of the detrimental effect of prehospital delay on morbidity and mortality, the National Heart Attack Alert Program5 advocates a goal of one hour (i.e., the “golden hour” similar to that in trauma care) from ACS symptom onset to opening the coronary artery by reperfusion or angioplasty. Unfortunately, the median prehospital delay times have remained far longer at 2.3 to 6 hours.6–8 Over three-quarters of this delay time is related to the decision process undertaken by the patient, with less than one-quarter related to transport time.9

To date, all interventions to reduce prehospital delay in ACS have involved community education strategies designed to educate the general public. 10 Interventions have focused on educating the public about the signs and symptoms of ACS, the importance of calling emergency services, and the availability of treatments such as fibrinolysis and primary coronary intervention. With few exceptions, these community-based interventions have failed to reduce prehospital delay.10

Recognizing the complex cognitive, social and emotional processes involved in having patients identify ACS symptoms correctly and seek care immediately, we conducted a randomized controlled trial to test an education and counseling intervention designed specifically for individuals at high risk for a future ACS event. The intervention was aimed at reducing the time from ACS symptom onset to arrival at the hospital by increasing patients’ knowledge about cardiac symptoms, and improving their attitudes and beliefs about seeking care immediately when they experience ACS symptoms by calling 911. The primary study hypothesis was that patients who received a face-to-face education and counseling intervention and who experienced symptoms of ACS during two-years of follow-up would have reduced prehospital delay time compared to control. Secondary hypotheses focused on use of emergency medical services (EMS) and aspirin. We also examined the effect of the intervention on emergency department (ED) utilization.

Methods

Following review and approval of the study protocol by the Institutional Review Boards at all the participating institutions, we enrolled 3,522 patients with diagnosed ischemic heart disease into a randomized controlled trial known as PROMOTION (Patient Response tO Myocardial Infarction following a Teaching Intervention Offered by Nurses) from 2002 to 2004 and were followed for two years following their enrollment. Participants provided written, informed consent prior to randomization. The study design has been described previously.11 Briefly, it consisted of randomization to one of two arms: 1) the experimental arm included a single, face-to-face educational session conducted by a nurse with expertise in cardiology, followed by telephonic reinforcement at one month by the same nurse, or 2) the control arm consisting of usual care. Physicians caring for patients and nurses collecting follow-up data were blinded to study assignment.

Sample

Patients were recruited from in-hospital cardiovascular and cardiac catheterization units and from a variety of out-patient clinics, cardiac rehabilitation programs and community medical practices in the United States (n=1985, 56%) and Australia or New Zealand (n=1537, 44%). Patients were eligible for the study if they had a diagnosis of ischemic heart disease, confirmed by their physician or hospital medical record, and if they lived independently (i.e., not in an institutional setting). Patients were excluded if they had any of the following: complicating serious co-morbidity such as a psychiatric illness or untreated malignancy, neurological disorder with impaired cognition, or inability to read or understand English.

Procedure

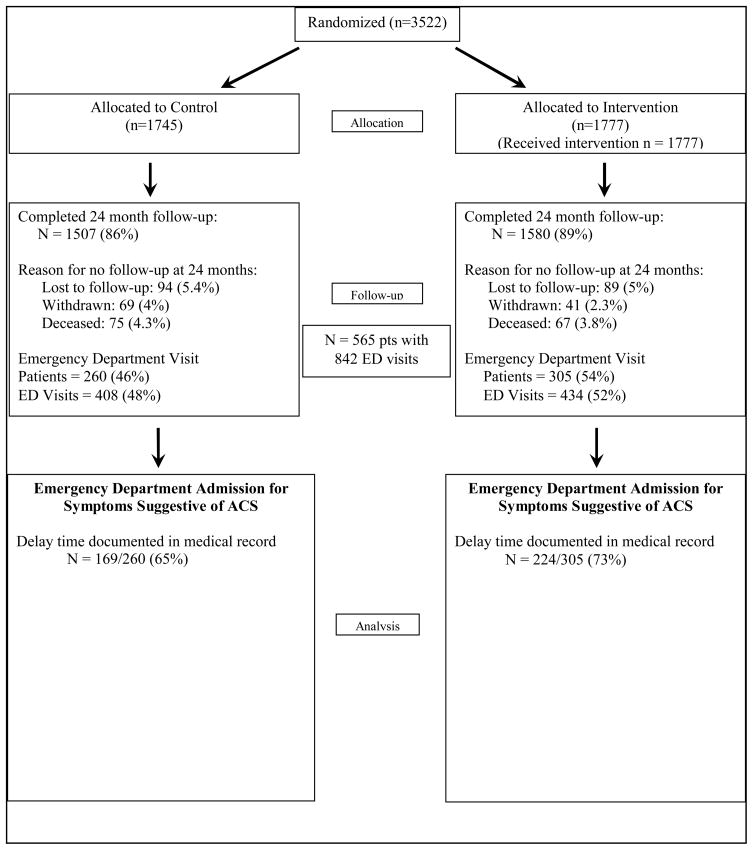

Data were collected in six sites: Los Angeles, California; Lexington, Kentucky; San Diego, California; Seattle, Washington; Sydney, Australia; and Auckland, New Zealand. The University of California, San Francisco served as the project and data coordinating center. Baseline data were collected by means of a face-to-face meeting conducted in a place convenient to the patient (e.g., out-patient clinic, physician’s office, or patient’s home) following enrollment and prior to randomization. All data were collected using standardized paper and pencil instruments. Subsequent data using similar questionnaires were collected at 3, 12, and 24 months in the physician’s office or patient’s home, or by telephone after the patients had received a mailed copy of the data collection instruments. A summary of the study design and number of participants at each data collection point is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram

All patients were asked to inform the research office using a 24-hour toll free number if they had sought medical treatment for symptoms of ACS. To encourage complete follow-up data, however, all participants were called every 6 months and asked if they had experienced ACS symptoms and sought medical care. In all cases of admission to the emergency department for a possible ACS event, medical records were reviewed to determine the admitting and discharge diagnoses, prehospital delay time, mode of transport to the hospital, and aspirin use prior to admission. Follow-up continued for two years. All data collected at each of the participating sites were entered via internet into a secure database specifically designed for the study with appropriate privacy safeguards as dictated by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Intervention

The intervention was based on Leventhal’s self regulatory model of illness behavior12,13 in which ACS symptoms serve as a stimulus that must be processed both cognitively and emotionally; an action plan is then developed and its effectiveness is appraised by the patient, with the plan revised based on that appraisal. Patients received education in the three areas recommended to physicians by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute Working Group on Educational Strategies to Prevent Prehospital Delay in Patients at High Risk for Acute Myocardial Infarction: namely, information about ACS, anticipated emotional issues and social factors that could affect delay.5

Information

Patients were given standardized information about typical and atypical symptoms of ACS and possible variability in symptom presentation. Patients were told that they might experience chest pressure or discomfort that was intermittent rather than constant, and that diaphoresis, shortness of breath, and pain radiation to parts of the body other than the left arm (e.g., neck or back) were also possible symptoms of ACS. They were advised to call EMS immediately. At the time of the development of the educational intervention, patients who had no contraindiciations were encouraged to take one non-enteric coated aspirin prior to arrival at the hospital as well as nitroglygerin (if prescribed), and this instruction was included.14

Emotional component

Patients were asked to anticipate the emotional responses to ACS symptoms that might lead to delay, as well as to discuss their previous experiences accessing the medical system. The rewards of seeking treatment immediately were emphasized and emotional issues were addressed through role playing scenarios that were standardized across intervention group patients.

Social Factors

Patients were asked to bring their spouse, another family member or friend to the intervention session whenever possible. These individuals were “deputized” to act as the decision maker if the patient hesitated to call EMS. The potential reaction of the family member was discussed (e.g., denial, fear, ambivalence, etc.) and the importance of and rewards for quick action were underscored.

An advisory form5 that included the appropriate steps to take with onset of ACS symptoms was provided at the end of the intervention session. Patients were asked to post the advisory form in a prominent place in the house (e.g., on the refrigerator or by the phone). The intervention was standardized with a flip chart so that patients and family members received the same information components, but it was tailored to the patient’s own past medical experience and unique living situation. The information was delivered in a quiet, private outpatient setting such as a room in the clinic office or the patient’s home and was approximately 40 minutes in length. One month following the initial intervention session, the nurse who had provided the intervention called each patient and reviewed the main points from the initial session. The average length of the phone call was 15 minutes.

Measurements

Prehospital delay

Time from symptom onset to hospital presentation was obtained from the hospital medical record or, in those cases with no notation in the medical record, from the EMS prehospital medical reports.

Mode of transportation

Emergency department records were used to identify mode of transport to the hosptial. To verify transport by the paramedic system, we checked all data against the EMS prehospital medical reports.

Aspirin use

Aspirin use prior to hospital admission was evaluated by review of the ED medical record and verified by patient interview following emergency department admission.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

All participants completed a paper and pencil questionnaire describing sociodemographic characteristics, insurance status, and clinical history. Race was obtained by self-report and was requested because previous researchers have identified race and/or ethnicity as variables influencing prehospital delay.2,8

Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about ACS

These variables were measured at baseline, 3 and 12 months in both experimental and control groups as a test of the fidelity of the intervention using the ACS Response Index, an instrument originally developed for the Rapid Early Reaction for Coronary Treatment (REACT) study to measure knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about coronary heart disease7 and modified for use in the current study.15 Reliability was tested using Cronbach’s alpha and was judged adequate at .82, .71 and .74 respectively for the three scales of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs.

Statistical Analyses

Baseline characteristics of the control and experimental groups were compared using Chi-square tests for categorical data and independent t-tests for continuous variables. To test the saliency of the intervention, we assessed knowledge, attitudes and beliefs over time (baseline, 3 and 12 months) using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).

Since prehospital delay time was positively skewed, we used log transformed prehospital delay times for all analyses to make the distribution more nearly Gaussian. Sample size was calculated based on the mean and median prehospital delay times previously identified in 474 AMI patients in sites similar to those proposed in the current study.16 In that study, mean delay was 11.2 (SD 21.6) hours with a median delay of 3.3 hours. Using the natural log of the transformed mean (1.4) and standard deviation (1.4), we targeted a 25 percent reduction in delay time, reflecting a small to medium effect size (0.2857, t (386)=1.966). Using alpha = 0.05 and beta = 0.20, data on 388 patients were required to have adequate power to detect a significant difference in the prehospital delay time between the two groups.17 Based on a previous study in which a reduction in delay to treatment of 30 minutes led to a significant reduction in morbidity and mortality,4 the target of a 25 percent reduction was identified as clinically significant.

A mixed linear model was used to assess the effect of the intervention on log transformed prehospital delay with the intercept parameters specified as random. In those cases where prehospital delay time was missing in the medical record or EMS record, values were not imputed. Similarly, a random-effects logistic model was used to compare the use of ambulance during ER visits and aspirin use between the experimental and control groups and missing values were not imputed. Random effects were used in all analyses to account for the within-patient correlation of the outcomes because some patients had more than one emergency visit. Treatment assignment, time since randomization, and the time-by-treatment interaction, as well as age, gender, BMI, insurance coverage for ambulance use, and medical history were treated as fixed effects based on previous research1,2,5,6 suggesting that these variables might influence patients’ adherence to the recommended actions, our interest in understanding if patients were more likely to follow recommendations in the time immediately following the intervention (i.e., within 6 months) compared to a time more distant from the intervention session, and baseline differences between the experimental and control groups. Tests were two-sided, and p-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were run using Stata 9.0 software (Stata Corp, College Station, TX or SPSS version15.0).

Results

On average, patients who enrolled in the study were 67 (SD 11) years old and 68% were male. The majority was married (71%), employed (72%), being care for by a cardiologist (83%), and had insurance for visits to the ED (96%). A check on randomization revealed no significant differences between groups on a variety of demographic and clinical variables except for body mass index (p=0.048), gender (with more females in the experimental group than control, p=0.02), and insurance for ambulance use (with more patients with insurance in the control group compared to the experimental group, p=0.04) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (N=3522)

| Patient Characteristics | Total | Experimental (n=1777) | Control (n=1745) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | 0.856 | |||

| <65 | 1352 | 690 (38.8%) | 662 (38.0%) | |

| 65–79 | 1751 | 876 (49.3%) | 875 (50.2%) | |

| 80+ | 417 | 211 (11.9%) | 206 (11.8%) | |

| Gender | 0.023 | |||

| Male | 2393 | 1176 (66.2%) | 1217 (69.7%) | |

| Female | 1129 | 601 (33.8%) | 528 (30.3%) | |

| Marital Status | 0.795 | |||

| Not currently married | 994 | 499 (28.5%) | 495 (28.9%) | |

| Married or cohabit | 2468 | 1251 (71.5%) | 1217 (71.1%) | |

| Working Status | 0.816 | |||

| Unemployed | 2517 | 1272 (71.8%) | 1245 (71.4%) | |

| Employed | 998 | 500 (28.2%) | 498 (28.6%) | |

| Education | 0.963 | |||

| Some High School | 557 | 280 (15.8%) | 277 (15.9%) | |

| Completed High School | 641 | 318 (17.9%) | 323 (18.5%) | |

| Some College/Technical | 1326 | 673 (37.9%) | 653 (37.5%) | |

| Completed College | 994 | 505 (28.4%) | 489 (28.1%) | |

| Annual Income | 0.550 | |||

| <$15,000 | 726 | 353 (22.2%) | 373 (23.6%) | |

| $15,000–$30,000 | 719 | 366 (23.0%) | 353 (22.4%) | |

| $30,000–$45,000 | 554 | 266 (16.7%) | 288 (18.2%) | |

| $45,000–$60,000 | 456 | 236 (14.8%) | 220 (13.9%) | |

| >60,000 | 715 | 370 (23.3%) | 345 (21.8%) | |

| Insurance | 0.809 | |||

| Uninsured, Govt., VA | 1774 | 890 (50.4%) | 884 (50.8%) | |

| Any Private | 1732 | 876 (49.6%) | 856 (49.2%) | |

| Insured for ambulance use | 0.044 | |||

| No | 353 | 196 (12.7%) | 157 (10.4%) | |

| Yes | 2698 | 1344 (87.3%) | 1354 (89.6%) | |

| Insured for visit to the ED | 0.775 | |||

| No | 141 | 73 (4.3%) | 68 (4.1%) | |

| Yes | 3231 | 1633 (95.7%) | 1598 (95.9%) | |

| Ethnicity | 0.900 | |||

| White | 3207 | 1617 (91.0%) | 1590 (91.1%) | |

| Non-White | 315 | 160 (9.0%) | 155 (8.9%) | |

| Asian-Pacific Islander | 126 | 62 (3.5%) | 64 (3.7%) | |

| Black | 62 | 33 (1.9%) | 29 (1.7%) | |

| Hispanic | 42 | 22 (1.2%) | 20 (1.1%) | |

| Native American | 33 | 17 (1.0%) | 16 (0.9%) | |

| Other | 52 | 26 (1.5%) | 26 (1.5%) | |

| History of Angina | 0.997 | |||

| No | 1365 | 695 (40.3%) | 670 (39.5%) | |

| Yes | 2056 | 1029 (59.7%) | 1027 (60.5%) | |

| History of MI | 0.619 | |||

| No | 1536 | 786 (45.4%) | 750 (44.1%) | |

| Yes | 1894 | 944 (54.6%) | 950 (55.9%) | |

| History of PTCA | 0.438 | |||

| No | 1813 | 908 (51.9%) | 905 (52.3%) | |

| Yes | 1666 | 841 (48.1%) | 825 (47.7%) | |

| History of stent | 0.815 | |||

| No | 2087 | 1050 (59.8%) | 1037 (60.0%) | |

| Yes | 1398 | 707 (40.2%) | 691 (40.0%) | |

| History of PTCA +/− stent | 0.880 | |||

| No | 1749 | 883 (50.2%) | 866 (49.9%) | |

| Yes | 1743 | 875 (49.8%) | 868 (50.1%) | |

| History of CABG | 0.866 | |||

| No | 1896 | 975 (55.0%) | 921 (52.9%) | |

| Yes | 1618 | 799 (45.0%) | 819 (47.1%) | |

| History of PVD | 0.228 | |||

| No | 2998 | 1530 (89.9%) | 1468 (88.2%) | |

| Yes | 367 | 171 (10.1%) | 196 (11.8%) | |

| History of diabetes | 0.108 | |||

| No | 2740 | 1382 (78.2%) | 1358 (78.4%) | |

| Yes | 759 | 385 (21.8%) | 374 (21.6%) | |

| History of stroke | 0.889 | |||

| No | 3116 | 1565 (89.4%) | 1551 (90.3%) | |

| Yes | 353 | 186 (10.6%) | 161 (9.7%) | |

| Current smoker | 0.380 | |||

| No | 3288 | 1665 (93.8%) | 1623 (93.3%) | |

| Yes | 227 | 110 (6.2%) | 117 (6.7%) | |

| History of smoking | 0.525 | |||

| No | 1311 | 681 (38.4%) | 630 (36.2%) | |

| Yes | 2204 | 1094 (61.6%) | 1110 (63.8%) | |

| History of hypercholesterolemia | 0.186 | |||

| No | 1164 | 601 (34.6%) | 563 (32.8%) | |

| Yes | 2288 | 1135 (65.4%) | 1153 (67.2%) | |

| History of hypertension | 0.260 | |||

| No | 1532 | 765 (43.7%) | 767 (44.5%) | |

| Yes | 1944 | 986 (56.3%) | 958 (55.5%) | |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 0.646 | |||

| No | 2343 | 1179 (66.8%) | 1164 (67.3%) | |

| Yes | 1153 | 587 (33.2%) | 566 (32.7%) | |

| Cardiologist | 0.743 | |||

| No | 573 | 296 (16.7%) | 277 (15.9%) | |

| Yes | 2933 | 1472 (83.3%) | 1461 (84.1%) | |

| Attended cardiac rehabilitation | 0.520 | |||

| No | 1595 | 837 (49.2%) | 758 (45.8%) | |

| Yes | 1763 | 865 (50.8%) | 898 (54.2%) | |

| BMI | 0.048 | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 1111 | 549 (32.4%) | 562 (34.1%) | |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | 1375 | 683 (40.3%) | 692 (42.0%) | |

| 30+ kg/m2 | 854 | 461 (27.2%) | 393 (23.9%) | |

| X (SD) | X (SD) | |||

| Score on ACS Response Index (% correct) | 70.9 (11.2) | 70.8 (11.5) | 0.987 |

Despite having a history of coronary heart disease, 38% of patients had significant gaps in knowledge about ACS at baseline, as documented by scores of less than 70% on the Knowledge Scale of the ACS Response Index. The mean cardiac knowledge score for the entire sample on the ACS Response Index was 71% (SD 12%) with a range of 8 to 100%.18 There was no significant difference in baseline knowledge scores on the ACS Response Index between the two treatment groups at baseline (Table 1). In comparing the groups over time, all three scales were significantly higher in the experimental group compared to the control group over time (p<0.0005), indicating that the intervention increased knowledge and influenced attitudes and beliefs in the hypothesized direction.

Clinical Outcomes

Of the 3522 subjects originally enrolled, 142 (4%) were deceased at 24 months, 75 (4.3%) in the experimental group and 67 (3.8%) in the control group (p = 0.426). One hundred eighty-three (5.2%) were lost to follow-up, and 110 (3.1%) withdrew from the study. Therefore, the two-year follow-up was conducted on 3087 (87.6%) subjects. A total of 565 (16.0%) patients presented to the ED with symptoms of ACS for a total of 842 admissions. Of the 565 patients, 260 (46%) were in the control group and 305 (54%) were in the experimental group. Of the 842 ED admissions, 408 (48%) were in the control group and 434 (52%) were in the experimental group. The patients who sought care for ACS symptoms are described in Table 2. Delay time was recorded in the medical record in 595 (71%) of the 842 cases. Data were available on the mode of transport in 708 (97.0%) cases and on the use of non-enteric coated aspirin by the patient prior to ED admission in 674 (92.3%) of cases.

Table 2.

Comparison of characteristics of patients admitted to the emergency department for ACS symptoms (N=565)

| Baseline characteristics | Experimental (n=305) | Control (n= 260) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographic Characterisitics | |||

| Age, Mean ± SD (years) | 67.5 ± 12.3 | 68.2 ± 10.8 | .53 |

| Female gender, %(n) | 38.0 (116) | 31.5 (82) | .11 |

| ≥ College education, %(n) | 33.8 (24) | 27.7 (23) | .48 |

| Annual household income < $30,000), %(n) | 29.2 (19) | 50.0 (39) | .02 |

| Fulltime or part-time employment | 28.1 (85) | 21.2 (55) | .06 |

| U.S. resident | 48.5 (148) | 48.8 (127) | .94 |

| Health insurance for ambulance | 86.7 (235) | 92.7 (217) | .03 |

| Cardiac Risk Factors, %(n) | |||

| Current smoker | 7.2 (22) | 5.4 (14) | .39 |

| Diabetes | 20.1 (61) | 26.5 (68) | .07 |

| Hypertension | 61.4 (183) | 62.3 (160) | .84 |

| Dyslipidemia | 66.8 (197) | 67.5 (172) | .87 |

| BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 | 43.7 (31) | 34.9 (29) | .32 |

| Sedentary lifestyle | 22.5 (16) | 17.9 (15) | .55 |

Clinical outcomes are summarized in Table 3. The median time from symptom onset to hospital admission was 2.20 hours for the experimental group compared to 2.25 hours for the control group. The regression coefficient for the treatment variable was the difference in log times between the experimental and control groups and this difference was not significant (p=0.40). Mean prehospital delay time was 22 minutes shorter on average in the experimental group than the control group, but this difference was not significant and was primarily caused by a few patients in the control group who incurred exceedingly long prehospital delay times (i.e., greater than 12 hours). In an unadjusted mixed linear model analysis, the intervention resulted in a decreased prehospital delay time of 3.3% (95% CI −10.9% to 4.3%, p=0.40) with the percent change calculated as the difference in prehospital delay times between the experimental and control groups divided by the control group prehospital delay time. When potentially confounding variables (i.e., time since randomization, age, gender, BMI, insurance for ambulance use and medical history) were adjusted in the analysis, the intervention resulted in a decreased prehospital delay time of 1.02% (95% CI −9.59 7.54, p=0.82).

Table 3.

Prehospital delay, EMS and aspirin use during two-years follow-up.

| Experimental | Control | |

|---|---|---|

| Prehospital delay ┼ | 317 ED visits (n = 224)§ |

278 ED visits (n= 169) |

| Median prehospital delay time (hours) | 2.20 | 2.25 |

| 25 percentile | 1.18 | 1.18 |

| 75 percentile | 4.69 | 5.28 |

| Mean prehospital delay time (± SD) | 4.29 (± 0.34) | 5.08 (± 0.69) |

| Transportation mode § | 373 ED visits (n = 305) |

334 ED visits (n = 260) |

| Ambulance/Helicopter: % (n) | 63.6 (194) | 66.9 (174) |

| Private car/other: % (n) | 58.7 (179) | 61.5 (160) |

| Aspirin use prior to ED arrival § | 367 ED visits (n = 259 ) |

307 ED visits (n =212 ) |

| Yes: % (n) | 22.3 (82) | 10.1 (31) |

| No: % (n) | 77.7(285) | 89.9 (276) |

Note:

Prehospital delay time (time from symptom onset to ED arrival) was obtained from patients’ medical records. Due to missing data, sample sizes in prehospital delay time, transportation mode, and aspirin use are not equivalent.

n refers to the number of patients in each group

Sixty-four percent of patients in the experimental group and 67% of patients in the control group used EMS. Comparing these values using an unadjusted random effects logistic model, the differences were not significant (p=0.89). However, using an adjusted random effects logistic model, we found an interaction between group assignment and time from randomization to symptom onset (p=0.009). We then compared patients who experienced symptoms within six months of study entry and those who experienced symptoms later than six months. Patients in the experimental group were more likely to use EMS if the ACS symptoms occurred early in the study, i.e., within the first 6 months following group assignment (p=0.036). It was also noted that when all patients who used EMS were analyzed by country, 66.7% were Australian while only 33.3% were from the U.S..

Approximately twice as many patients in the experimental group compared to control group took aspirin following symptom onset (22.3% vs 10.1% respectively) and the difference by group assignment was significant according to a mixed models random effects analysis (p=.024). Using an adjusted random effects logistic model, the time from randomization to ED visit was a significant predictor of aspirin use (OR 1.93, CI 1.09–3.43, p=0.024).

Receiving education and counseling about the need to respond quickly to ACS symptoms did not result in increased ED use. In fact, over the two years of follow-up 17.5% of patients in the control group sought care in an ED for symptoms of ACS compared to 14.6% of patients in the experimental group over the two years of follow-up. This difference in ED utilization between groups was not significant (p>0.05).

Discussion

Today almost 14 million Americans have established coronary artery disease, which increases their risk for a future ACS event.19 Delay in contacting the health care system in the face of cardiac symptoms remains a major obstacle to definitive treatment of patients with acute myocardial infarction and may contribute to out-of-hospital cardiac deaths. The study reported here was the first randomized controlled trial designed specifically for a population at high risk for a future ACS event and targeting a reduction in prehospital delay. We documented the effects of a face-to-face, tailored education and counseling intervention on prehospital delay time (the primary hypothesis), as well as EMS and aspirin use, as well as utilization of the ED (secondary hypotheses). The primary hypothesis was rejected. While aspirin use was significantly higher in the experimental group, the use of EMS was not significantly different. However, utilization of ED resources was not significantly increased by the intervention.

The intervention was designed to encourage patients to personalize the message to seek care quickly in the face of ACS symptoms and to counter emotional coping mechanisms such as denial that might lead to prolonged prehospital delay time. The intervention protocol was based on the recommendations of the National Heart Attack Alert Program5 and the findings were particularly disappointing given the tailored nature of the intervention and the high risk status of the sample for a future ACS event. Unlike previous interventions designed for community-dwelling individuals,7,10 the current study was tailored for patients aware of their risk for a future ACS event who could be expected to be more attentive to health messages than individuals living in the community.

Upon reflecting on the negative study findings of no difference in median prehospital delay times between the two experimental groups, several interpretations can be offered. First, data collection may have provided an unintended form of intervention in the control group. All patients enrolled in the current study completed questionnaires at baseline, 3 and 12 months following enrollment and responded to questions in which they were asked to identify cardiac symptoms, describe their attitudes toward seeking help quickly if symptoms occurred, and state the level of their belief that the medical system had treatments that would help them if they sought care quickly. Reflecting on these questions at three different times and actively responding in writing to each of them may have sensitized control patients to the importance of seeking care early. Perhaps a third study arm that represented a true control without periodic assessment of knowledge, attitudes and beliefs would have revealed that the data collection process itself was a form of intervention. The fact that, with the exception of the Physicians Health Study (median delay time of 114 minutes),20 the delay times in both the experimental and control groups was shorter than in all previous studies reported to date10 supports this interpretation.

Second, another explanation for the lack of effect of the face-to-face tailored intervention may be that the information presented did not address the variability of onset and the differing symptoms of ACS adequately or was not of sufficient intensity or duration to address the patients’ denial or inappropriate attribution of symptoms. The education and counseling session was delivered by a research nurse, not the patient’s physician. The latter may have been able to adapt the information provided the patient to the unique medical history, including the nature of previous ACS symptoms and patterns of response. Similarly, the fact that patients in the experimental group were more likely to call the EMS if ACS symptoms occurred early in the study (i.e., in the first six months from enrollment) suggests that repetition of the information might increase the saliency of the intervention.

A third interpretation relates to difference between the two study groups. Despite randomization, there were significantly more women in the experimental group than the control group (34 vs. 30 percent respectively, p=0.02). This difference may have contributed to the finding of no difference in median delay times, although gender was used as a covariate in the analysis. Although gender was not significantly different in the two groups who sought care for ACS symptoms (38 vs 32 percent in the experimental and control groups respectively, p=0.11), the difference in percentages may have favored longer median delay times in the experimental group. Some investigators6 have noted that women delay longer than men in seeking care for cardiac symptoms, although the reason for this difference by gender remains unknown. Similarly, the two groups who presented to the ED for symptoms of ACS were significantly different in their annual incomes and ambulance insurance, with the experimental group reporting lower income and less insurance coverage. Both factors would favor longer delays in the experimental group if patients were concerned about the cost of care and therefore may have contributed to the finding of no difference between the groups; however, these differences were handled as covariates in the analysis and therefore do not provide a strong explanation for the findings of no difference in prehospital delay times.

We were surprised at the high EMS use in both groups, which was twice the level of the 33% EMS use documented in REACT at baseline7 or the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction.21 Our findings may be a reflection of the large proportion of patients recruited from Australia and New Zealand (44%) where ambulance use is generally high and is covered by universal health care. In fact, 87% of all patients in the study had insurance coverage for EMS use, which may have contributed to the high ambulance use and the relatively short prehospital delay. Many investigators7,22 have noted the importance of accessing EMS to reduce prehospital delay time, as well as minimize delay to treatment once the patient is admitted to the hospital.

Although the intervention did not influence prehospital delay times or EMS use, it did result in a significantly higher percentage of patients who took aspirin in the face of acute symptoms. It is important to note that researchers have suggested that self treatment is a source of delay,23 and therefore the recommendation to take aspirin prior to hospital arrival is no longer given.24 However, our findings suggest that patients are willing to adopt this behavior, which is a relatively simple one compared to calling EMS. The significant difference between groups on this one outcome underscores the complexity of designing an intervention that will reduce the many psychological barriers to calling 911 that exist for patients and their family members in the face of ACS symptoms. Behaviors such as taking aspirin appear to be easier to change than calling EMS or seeking care in an ED immediately upon onset of cardiac symptoms.

One of the concerns about conducting a large-scale intervention to decrease prehospital delay in ACS is that patients will become anxious and emergency department utilization will increase inappropriately. It is important to note that the intervention did not increase emergency room use in the experimental group, a finding that is similar to that of other community intervention studies.7,18,25.

Conclusion

A relatively short, one-on-one education and counseling intervention significantly increased knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about ACS and response to ACS symptoms. The intervention did not reduce pre-hospital delay time or increase EMS use, although it did increase the patients’ use of aspirin prior to arrival at the hospital. The decision to seek care promptly with the onset of ACS symptoms and use of EMS rather than other modes of transportation continues to be a significant public health challenge. Further research is required to determine how best to encourage patients who experience symptoms of ACS to seek care promptly.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Beverly Carlson, RN, MS, Sharp HealthCare, San Diego; Leanne M. Aitken, RN, PhD, Griffith University, Brisbane Australia; Andrea Marshall, RN, PhD, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia; Patricia Howard, RN, PhD, University of Kentucky; and Valerie Rose, BS, University of Washington, for their contributions to the study related to subject enrollment and data acquisition. They would also like to acknowledge Yoshimi Fukuoka, RN, PhD, University of California, San Francisco for her assistance with the statistical analysis.

Funding Source

The study was funded by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Nursing Research (R01 NR05323), Kathleen Dracup, Principal Investigator. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

What is Known

1. The time from the onset of symptoms of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) to arrival at the hospital continues to be far too long to achieve optimal benefit from reperfusion therapy in a majority of cases.

2. Three-quarters of the time related to prehospital delay in ACS is the result of patients’ failure to call the emergency medical system (EMS).

3. Community education programs have been ineffective in changing prehospital delay times in ACS over the past two decades.

What this Article Adds

4. This was the first randomized clinical trial of an educational intervention for patients at high risk for ACS.

5. The intervention did not result in reduced prehospital delay or increased EMS use, but resulted in increased aspirin use by patients prior to hospital admission.

Journal Subject Code: 3 Acute coronary syndrome, 117 Behavioral/psychosocial treatment

Clinical Trial Registration: URL #NCT00734760 http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00734760

Disclosures

No real or perceived conflicts of interest exist for any of the authors of this manuscript.

References

- 1.McGinn AP, Rosamond WD, Goff DC, Jr, Taylor HA, Miles JS, Chambless L. Trends in prehospital delay time and use of emergency medical services for acute myocardial infarction: experience in 4 US communities from 1987–2000. American Heart Journal. 2005;150:392–400. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.03.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldberg RJ, Steg PG, Sadiq I, Granger CB, Jackson EA, Budaj A, Brieger D, Avezum A, Goodman S. Extent of, and factors associated with, delay to hospital presentation in patients with acute coronary disease (the GRACE registry) American Journal Cardiology. 2002;89:791–796. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zahn R, Schiele R, Gitt AK, Schneider S, Seidl K, Voigtlander T, Zahn R, Schiele R, Gitt AK, Schneider S, Seidl K, Voigtlander T, Gottwik M, Altmann E, Gieseler U, Rosahl W, Wagner S, Senges J Maximal Individual Therapy in Acute Myocardial Infarction (MITRA) Study Group. Myocardial Infarction Registry Study Group. Impact of prehospital delay on mortality in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with 4 angioplasty and intravenous thrombolysis. American Heart Journal. 2001;142(1):105–111. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2001.115585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rawles JM. Quantification of the benefit of earlier thrombolytic therapy:Five year results of the Grampian Region Early Anistreplase Trial (GREAT) Journal American College Cardiology. 1997;30:1181–1186. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00299-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dracup K, Alonzo AA, Atkins JM, Bennett NM, Braslow A, Clark LT, Eisenberg M, Ferdinand KC, Frye R, Green L, Hill MN, Kennedy JW, Kline-Rogers E, Moser DK, Ornato JP, Pitt B, Scott JD, Selker HP, Silva SJ, Thies W, Weaver WD, Wenger NK, White SK National Heart Attack Alert Program. The physician’s role in minimizing prehospital delay in patients at high risk for acute myocardial infarction: recommendations from the National Heart Attack Alert Program. Working Group on Educational Strategies to Prevent Prehospital Delay in Patients at High Risk for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Annals Internal Medicine. 1997;126:645–651. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg RJ, Gurwitz JH, Gore JM. Duration of and temporal trends (1994–1997) in prehospital delay in patients with acute myocardial infarction: the second National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Archives Internal Medicine. 1999;159:2141–2147. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luepker RV, Raczynski JM, Osganian S, Goldberg RJ, Finnegan JR, Jr, Hedges JR, Goff DC, Jr, Eisenberg MS, Zapka JG, Feldman HA, Labarthe DR, McGovern PG, Cornell CE, Proschan MA, Simons-Morton DG. Effect of a community intervention on patient delay and emergency medical service use in acute coronary heart disease: The Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment (REACT) trial. JAMA. 2000;284:60–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dracup K, Moser D, McKinley S, Bal lC, Yamasaki K, Kim C, Nansalip P, Doering L, Caldwell M. An international perspective of the time to presentation with myocardial infarction. Journal Nursing Scholarship. 2003;35:317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2003.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rassmussen CH, Munck A, Kragstrup J, Haghfelt T. Patient delay from onset of chest pain suggesting acute coronary syndrome to hospital admission. Scandanavian Cardiovascular Journal. 2003;37:183–186. doi: 10.1080/14017430310014920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kainth A, Hewitt A, Sowden A, Duffy S, Pattenden J, Lewin R, Watt I, Thompson D. Systematic review of interventions to reduce delay in patients with suspected heart attack. Emergency Medicine Journal. 2004;21:506–508. doi: 10.1136/emj.2003.013276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dracup K, McKinley S, Riegel B, Mieschke H, Doering LV, Moser DK. A nursing intervention to reduce prehospital delay in acute coronary syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Journal Cardiovascular Nursing. 2006;21:186–193. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200605000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leventhal H, Meyer D, Narenz D. The common sense representation of illness danger. In: Rachman S, editor. Medical Psychology. Vol. 2. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon; 1980. pp. 7–30. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Kitas GD. The common-sense model of self-regulation of health and illness: How can we use it to understand and respond to our patients’ needs? Rheumatology. 2007;46:904–906. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hennekens CH, Dyken ML, Fuster Aspirin as a therapeutic agent in cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 1997;96:2751–2753. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Riegel B, McKinley S, Moser DK, Meischke H, Doering L, Dracup K. Psychometric evaluation of the acute coronary syndrome (ACS) Response Index. Research in Nursing and Health. 2007;30:584–594. doi: 10.1002/nur.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gurwitz JH, McLauglin TJ, Willison DJ, Guadagnoli E, Hauptman PJ, Xiaoming G, Soumerai SB. Delayed hospital presentation in patients who have had acute myocardial infarction. Annals Internal Medicine. 1997;126:593–599. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-126-8-199704150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dracup K, McKinley S, Doering L, Riegel B, Meischke H, Moser DK, Pelter M, Carlson B, Aitken L, Marshall A, Cross R, Paul SM. Acute coronary syndrome: What do patients know? Archives Internal Medicine. 2008;168:1049–1054. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.10.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosamond W, Flegal K, Friday G, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2007 Update: A Report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2007;115:169–171. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.179918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ridker PM, Manson JE, Goldhaber SZ, Hennkens CH, Buring JE. Comparison of delay times to hospital presentation for physicians and non physicians with acute myocardial infarction. American Journal Cardiology. 1992;70:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(92)91381-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Canto JG, Zalenski RJ, Ornato JP, Rogers WJ, Kief CI, Magid D, Shlipak MG, Frederick PD, Lambrew CG, Littrell KA, Barron HV National Registry of Myocardial Infarction 2 Investigators. Use of emergency medical services in acute myocardial infarction and subsequent quality of care: observations from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction. Circulation. 2002;106:3018–23. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000041246.20352.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchings CB, Mann NC, Daya M, Jui J, Goldberg R, Cooper L, Goff DC, Jr, Cornell C Rapid Early Action for Coronary Treatment study. Patients with chest pain calling 911 or self-transporting to reach definitive care: which mode is quicker? American Heart Journal. 2005;150:e1–2. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(03)00510-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dracup K, McKinley SM, Moser DK. Australian patients’ delay in response to heart attack symptoms. Medical Journal Australia. 1997;166:233–236. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moser DK, Kimble LP, Alberts MJ, et al. Reducing delay in seeking treatment by patients with acute coronary syndrome and stroke: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on cardiovascular nursing and stroke council. Circulation. 2006;114:168–182. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho MT, Eisenberg MS, Litwin PE, Schaeffer SM, Damon SK. Delay between onset of chest pain and seeking medical care: the effect of public education. Annals Emergency Medicine. 1989;18:727–731. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(89)80004-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]