Abstract

Background

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatricians become knowledgeable in and comfortable with providing palliative care.

Objective

The study goals included: determining the extent of training, knowledge, experience, comfort and competence in palliative care communication and symptom management of pediatric residents and fellows; obtaining residents' and fellows' views on key palliative care concepts; identifying topics and methods for palliative care education; and identifying differences in responses between residents and fellows.

Design/Methods

In academic year 2006–2007 pediatrics residents and fellows completed a survey on: training, experience, knowledge, competence, and comfort in delivering palliative care; palliative care practices; and suggestions for delivering palliative care education.

Results

Fifty-two (60%) and 44 (62%) residents and fellows respectively completed the survey. Residents and fellows described none to moderate levels of training, experience, knowledge, competence and comfort in palliative care. Most respondents said they would benefit from more formal palliative care training. Respondents identified discussing prognosis, delivering bad news, and pain control as the three most important areas of needed education. Learning about supporting families spiritually and emotional support for physicians were among the least important educational areas identified. Respondents recommended delivering education via observation, bedside teaching, and participation in multidisciplinary groups.

Conclusions

Efforts to improve education in pediatric palliative care are needed. A palliative care team could facilitate palliative care education through engaging trainees in “real-life” interactions. The role of physicians in providing spiritual support and the need for educating physicians in obtaining emotional support for themselves merit further investigation.

Introduction

Over 50,000 children in the United States die every year and more than 500,000 children annually have life-threatening conditions.1–3 One study from the 1980s showed that pediatrics residents care for an average of 35 children who die during their first 2½ years of training.4 Today this number may be larger due to the higher acuity of hospitalized children.5 Fellows, particularly those in neonatology, hematology/oncology, and critical care medicine, likely care for even more terminally ill children during their training than do residents. The exposure of pediatrics residents and fellows to dying children and their families necessitates that trainees receive good education in palliative care.

The need for quality education in pediatric palliative care has been recognized for some time.5–8 In 2000, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that children living with a life-threatening or terminal condition have access to quality pediatric palliative care throughout the course of their illness.9 The AAP also recommended that generalist and subspecialty pediatricians, including residents and fellows, should become knowledgeable in and comfortable with providing palliative care.9 The Accreditation Council on Graduate Medical Education now requires that pediatric training programs include formal instruction related to the “impact of chronic diseases, terminal conditions, and death on patients and their families.”10

Despite the exposure of pediatricians to children with life-limiting conditions and endorsements by national organizations that education in palliative care is important, evidence suggests that pediatricians lack sufficient palliative care knowledge.5 Studies of bereaved family members report dissatisfaction with the care their children received regarding communication at the end of life and pain and symptom management.11–13 Studies of residents have demonstrated inadequate training, experience and comfort in palliative care.5,7,14,15

We adapted a published survey to determine the status of resident and fellow education in palliative care prior to the initiation of educational efforts specific to palliative care. The goals of the study included: (1) determining the extent of training, knowledge, experience, comfort, and perceived competence in palliative care communication and symptom management for pediatric residents and fellows; (2) obtaining residents' and fellows' views on key palliative care concepts; (3) identifying preferred topics and methods for palliative care education; and (4) identifying differences between residents and fellows.

Methods

Participants and study hospital

All pediatrics residents and fellows enrolled in the training program at the study hospital, an urban academic tertiary care pediatric hospital, between August 23, 2006 and February 1, 2007 were asked to complete a survey. The hospital's pediatrics residency program included 86 residents (81% females), 30 first-years, 30 second-years, and 26 third-years. There were 73 fellows (71% females) representing 14 subspecialties.

Formal resident training related to palliative care at the study hospital included: a lecture on pain control; a conference with parents of chronically ill or deceased children; a 2-hour seminar for first-year residents on giving bad news; quarterly case discussions at ethics grand rounds; and monthly debriefing sessions for residents during their intensive care unit and hematology/oncology rotations. The residency curriculum includes a minimum of 2 months of oncology, 3 months of neonatology and 2 months of pediatric intensive care. Fellow training varied based on subspecialty. A formal palliative care consultation program was introduced at the study hospital in January 2007.

The survey

The survey, adapted from Kolarik et al.,14 has four parts. The first asks for basic demographic information with specific questions about education in and exposure to palliative care-related issues. The second part asks participants to rate their formal training, personal experience as a participant and observer, knowledge, competence, and comfort on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = none, 2 = minimal, 3 = moderate, 4 = good, 5 = exceptional) in two domains of palliative care: communication and symptom management. “Formal training” was defined as amount of workshops, lectures, role modeling, and teaching on rounds in the specified area. “Personal experience as a participant” meant direct patient care responsibility in the specified area while “personal experience as an observer” meant observing patient care without directly examining patients, writing orders, or otherwise assuming responsibility for the patients' experiences. “Knowledge” referred to existing personal fund of knowledge in the specified area, “competency” to the ability to perform the specified task, and “comfort” to personal level of psychological/emotional ease in the specified area. The third part asks participants to rate their level of agreement with eleven general statements about palliative care using a 6-point Likert scale (6 = totally agree, 5 = mostly agree, 4 = somewhat agree, 3 = agree a little, 2 = unsure, and 1 = disagree). The fourth part asks participants to rank-order, according to preference, 11 training areas in palliative care and 9 methods for learning palliative care.

Our survey differed from the original in that: we included fellows; we asked about the role of physicians in providing spiritual support to dying children and their families; we asked participants to rank-order preferred methods of education; we modified or omitted items related to management of children with bowel obstruction, nausea, and severe fatigue to make the survey more compact and less specialized; and we omitted some items based on pertinence to the study institution. The adaptations were based on input from the pediatric palliative care clinicians at the study site. Surveys are available upon request.

Surveys were e-mailed to residents and fellows and made available after regular lectures. Study participation was completely voluntary. Survey responses did not include any personal identifying information. Residents and fellows returned completed surveys anonymously, either by mail or by placing them in centrally located folders. The study was submitted to the hospital's Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt.

Data management and statistical analysis

Data were reviewed for accuracy and verified by two independent researchers. We translated all Likert-scale responses into ordinal numbers and present group medians, modes, and ranges. Due to the discrete and ordinal nature of the data, we compared responses to the Likert-scale questions using a two-sided Mann-Whitney test that simultaneously tests for the shift in mean and median.16 We considered differences with a p < 0.05 statistically significant. We translated the rank order lists into ordinal numbers, calculated means, and present the final rank-ordered list using the calculated mean values. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 12.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

We received 96 surveys. Fifty-two (60%) residents and 44 (62%) fellows completed the survey. Table 1 shows the basic demographics of respondents. All but 6 surveys (3 from residents and 3 from fellows) were returned prior to the palliative care consult team's initiation.

Table 1.

Resident and Fellow Demographics and Exposure to Palliative Care and Pediatric Deaths

| Residents n (%) | Fellows n (%) | All n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Gender | Female | 40 (77%) | 32 (73%) | 72 (75%) |

| Age (years) | 25–29 | 45 (87%) | 8 (18%) | 53 (55%) |

| 30–34 | 6 (12%) | 31 (71%) | 37 (39%) | |

| 35–59 | 1 (2%) | 5 (11%) | 6 (6%) | |

| Exposure to palliative care | ||||

| Has previous PC training | 24 (46%) | 28 (64%) | 52 (54%) | |

| Cared for a child who might have benefited from PC | 43 (83%) | 34 (77%) | 77 (80%) | |

| Had a friend or family member with a life-threatening illness | 34 (65%) | 33 (75%) | 67 (70%) |

| Residents Mean (range) | Fellows Mean (range) | All Mean (range) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure to Dying Patients | |||

| Number of patients trainees cared for who died | 5.1 (0–30) | 9.5 (1–50) | 7.1 (0–50) |

| Number of patients trainees cared for with terminal conditions (likely to die within 6 months) | 11.3 (0–60) | 15.6 (0–100) | 13.2 (0–100) |

PC, palliative care.

Table 1 also shows the exposure to palliative care and exposure to dying patients of resident and fellow respondents. The reported number of patients who died while being cared for by residents and fellows increased by trainee year. First-year residents cared for a mean of 1.5 patients who died compared to a mean of 9 reported by third-year residents. First-year fellows cared for a mean of 5.3 patients who died compared to a mean of 16.3 reported by fourth-year fellows. Similarly, the reported number of patients with terminal conditions cared for by residents and fellows increased by trainee year. First-year residents cared for a mean of 4.8 patients with terminal conditions compared to a mean of 19.5 reported by third-year residents. First-year fellows cared for a mean of 17.1 patients with terminal conditions compared to a mean of 36.7 reported by fourth-year fellows.

The responses to items asking residents and fellows to rate their training, experience (both as a participant and as an observer), knowledge, competency, and comfort level for items related to palliative care communication and symptom management are shown in Tables 2 and 3. Based on the median responses, no items received a rating above moderate for either residents or fellows. The only items that achieved a moderate rating for residents were those asking about experience as an observer in conducting a family conference to discuss the new diagnosis of a life-threatening illness and providing adequate pain control. Fellow responses were in the minimal to moderate range for all items. Resident and fellow responses differed statistically in all areas except: training in conducting family conferences to discuss a new diagnosis of a life-threatening illness; including children in discussions about preparing for death; providing spiritual support; and providing care related to gastrointestinal symptoms. In those areas residents and fellows reported none to minimal training.

Table 2.

Resident and Fellow Responses to Items Pertaining to Palliative Care Communication

| |

|

Residents |

Fellows |

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Domain | Median | Mode | (Range) | Median | Mode | (Range) | p Valuea |

| Discussing with patients and families the transition from a curative to a palliative approach | Training | 2 | 1 | (1–3) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 0.044 |

| Experience-P | 2 | 1 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Experience-O | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Knowledge | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Competency | 2 | 2 | (1–3) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Comfort | 2 | 2 | (1–3) | 2.5 | 2 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Conducting a family conference to discuss the new diagnosis of a life-threatening illness | Trainingb | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 0.142 |

| Experience-P | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Experience-O | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | 0.008 | |

| Knowledge | 2 | 2 | (1–5) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Competency | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Comfort | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Including children in discussions about preparing for death | Trainingb | 1 | 1 | (1–3) | 2 | 2 | (1–3) | 0.087 |

| Experience-P | 1 | 1 | (1–3) | 2 | 4 | (1–5) | 0.002 | |

| Experience-O | 2 | 1 | (1–4) | 2 | 4 | (1–5) | 0.003 | |

| Knowledge | 1.5 | 1 | (1–3) | 2 | 3 | (1–4) | 0.002 | |

| Competency | 1 | 1 | (1–3) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 0.003 | |

| Comfort | 1 | 1 | (1–3) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 0.007 | |

| Discussing code status with the family of a child with a life-threatening illness | Training | 2 | 2 | (1–5) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 0.045 |

| Experience-P | 2 | 1 & 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Experience-O | 2 | 2 | (1–5) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Knowledge | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Competency | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Comfort | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Providing spiritual support for dying children and their families | Trainingb | 1 | 1 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–3) | 0.141 |

| Experience-P | 1 | 1 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Experience-O | 2 | 1 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Knowledge | 2 | 1 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 0.001 | |

| Competency | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Comfort | 1 | 1 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 0.001 | |

Values based on mean of Likert-scale responses (1 = none, 2 = minimal, 3 = moderate, 4 = good, 5 = exceptional).

Obtained using two-sided Mann-Whitney Test comparing residents and fellows.

Indicates domain where the difference in mean responses between residents and fellows is not statistically significant.

P, participant; O, observer.

Table 3.

Resident and Fellow Responses to Items Pertaining to Palliative Care Symptom Management

| |

|

Residents |

Fellows |

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Domain | Median | Mode | (Range) | Median | Mode | (Range) | p Valuea |

| Providing adequate pain control for pediatric patients with life-threatening illnesses | Training | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 0.019 |

| Experience-P | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Experience-O | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (2–5) | 0.001 | |

| Knowledge | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Competency | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Comfort | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (2–5) | <0.001 | |

| Recognizing the signs of impending death for terminal pediatric patients | Training | 2 | 2 | (1–3) | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | <0.001 |

| Experience-P | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 4 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Experience-O | 2 | 2 | (1–5) | 3 | 3 & 4 | (1–5) | <0.001 | |

| Knowledge | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Competency | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | <0.001 | |

| Comfort | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | 0.044 | |

| Providing care for terminally ill children with GI symptoms (i.e., nausea or constipation) | Trainingb | 2 | 1 | (1–4) | 2 | 1 | (1–4) | 0.161 |

| Experience-P | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | 0.016 | |

| Experience-O | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | 0.011 | |

| Knowledge | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | 0.031 | |

| Competency | 2 | 2 | (1–3) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | 0.001 | |

| Comfort | 2 | 2 | (1–4) | 3 | 3 | (1–4) | 0.019 | |

Values based on mean of Likert-scale responses (1 = none, 2 = minimal, 3 = moderate, 4 = good, 5 = exceptional).

Obtained using two-sided Mann-Whitney Test comparing residents and fellows.

Indicates domain where the difference in mean responses between residents and fellows is not statistically significant.

P, participant; O, observer; GI, gastrointestinal.

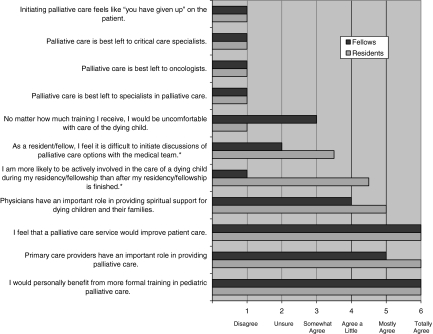

Median responses to the 11 general statements regarding palliative care are shown in Figure 1. Residents and fellows agreed that they would personally benefit from additional formal training in pediatric palliative care, that primary care clinicians have an important role in providing palliative care, and that a palliative care service would improve patient care. Residents and fellows disagreed that palliative care is best left to oncologists, critical care specialists, or palliative care specialists and that initiating palliative care feels like “you have given up” on the patient. Fellows, more than residents, thought they would be actively involved in caring for dying children after their training and felt more comfortable with initiating discussions of palliative care options with the medical team.

FIG. 1.

Resident and fellow responses to items about general palliative care concepts. *Indicates item with statistically significant difference in responses between residents and fellows based on Mann-Whitney test p < 0.05.

Table 4 shows the rank-order of topics of interest in palliative care for residents and fellows. Residents and fellows considered discussing prognosis, pain control, and delivering bad news most important. The topic considered least important for both residents and fellows was emotional support for physicians. Providing spiritual support for families was among the three least important topics for both residents and fellows.

Table 4.

Rank Order of Areas of Importance in Palliative Care Education

|

Residents |

Fellows |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Area | Mean | Rank | Area | Mean |

| 1 | Discussing prognosis | 3.3 | 1 | Discussing prognosis | 3.2 |

| 2 | Delivering bad news | 3.3 | 2 | Pain control | 3.6 |

| 3 | Pain control | 3.4 | 3 | Delivering bad news | 3.9 |

| 4 | Discussing code status | 4.4 | 4 | Including children in discussions about end-of-life care | 4.4 |

| 5 | Including children in discussions about end-of-life care | 5.0 | 5 | Discussing code status | 4.8 |

| 6 | Role of primary care providers in end-of-life care | 6.2 | 6 | Treatment of GI symptoms | 5.7 |

| 7 | Home hospice care | 6.8 | 7 | Home hospice care | 5.9 |

| 8 | Treatment of GI symptoms | 6.8 | 8 | Spiritual support for families | 6.7 |

| 9 | Spiritual support for families | 7.7 | 9 | Role of primary care providers in end-of-life care | 7.0 |

| 10 | Emotional support for physicians | 8.1 | 10 | Emotional support for physicians | 7.9 |

GI, gastrointestinal.

Table 5 depicts the rank order of preferred methods of education for residents and fellows. Learning via observing “real-life” interactions, bedside teaching and small multidisciplinary groups were the three methods most preferred by residents and fellows. The least preferred methods of learning for both groups were using standardized patients/families, handouts and Web-based tools.

Table 5.

Rank Order of Preferred Methods for Delivering Palliative Care Education

|

Residents |

Fellows |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Methods | Mean | Rank | Methods | Mean |

| 1 | Observing “real-life” interactions | 1.6 | 1 | Small multidisciplinary groups | 2.1 |

| 2 | Bedside teaching | 3.1 | 2 | Observing “real-life” interactions | 3.0 |

| 3 | Small multidisciplinary groups | 3.1 | 3 | Bedside teaching | 3.5 |

| 4 | Small groups of residents only | 3.4 | 4 | Small groups of fellows only | 3.6 |

| 5 | Lectures | 5.7 | 5 | Lectures | 4.9 |

| 6 | Web-based tools | 6.5 | 6 | Web-based tools | 6.2 |

| 7 | Handouts discussing relevant topics | 6.5 | 7 | Handouts discussing relevant topics | 6.3 |

| 8 | Standardized patients/families | 6.5 | 8 | Standardized patients/families | 6.5 |

Discussion

Overview

Our study assessed the current state of palliative care education for residents and fellows at one hospital and suggests directions for future education in pediatric palliative care. Overall, residents reported mainly no or minimal training, knowledge, experience, comfort, and competence in palliative care communication and symptom management. Fellow responses were in the minimal to moderate range, suggesting that subspecialty training not specific to palliative care, leads to only modest improvements in palliative care knowledge and skills. In the original study, performed in 2003 at an academic pediatric hospital without a palliative care team, Kolarik et al.14 reported similar findings, although they did not survey fellows. These similarities suggest that inadequate education in palliative care may be widespread and reinforces the need to improve education in palliative care during residency and fellowship.

Education

What is the best way for trainees to learn palliative care approaches? Our respondents indicated a preference for education via observation, bedside teaching, and participation in multidisciplinary groups. A formal palliative care team could facilitate learning by each of these methods. In the original study, Kolarik et al.14 postulated that not having a formal palliative care team limits mentorship and role modeling. Moreover, they noted that limited training for attending physicians in both delivering and teaching palliative care may also contribute to trainees' inadequate palliative care education.14

Our data show that the average number of deaths experienced by residents and fellows was lower than expected compared to the study by Sack et al.,4 although similar to that found by Kolarik et al.14 and by Tanz and Charrow.17 While one can imagine a number of possible explanations for this finding (including poor recall, improvements in medical care leading to fewer deaths, and/or more management of terminally ill patients outside the hospital) these results indicate that educators need to find creative methods for including trainees in the management of palliative care patients and families, particularly if many such patients receive their end-of-life care at home. Attending clinicians need to make extensive efforts to include trainees in their “real-life” interactions with patients and families on in-patient units, in day hospitals, and in clinics. Additionally, in-home visits may improve trainees' appreciation of the advantages and difficulties associated with the complex symptom management and treatment regimens required when caring for palliative care patients at home.

If a palliative care team exists, how can it best enhance the teaching of trainees? According to our study, trainees most want to learn about discussing prognosis, delivering bad news, and pain control. Kolarik et al.14 also suggested that palliative care education could focus initially on teaching pain management and communication skills. While these subject areas are important, trainee preferences may not adequately reflect future practice needs, which faculty clinicians might understand better.

Spiritual and emotional support

Two areas identified in both studies as being less important to trainees, spiritual support for families and emotional support for physicians, merit discussion.14

In our study, residents and fellows reported none to minimal training in providing spiritual support for dying children and their families, and they expressed some agreement with the statement, “Physicians have an important role in providing spiritual support for dying children and their families.” Yet, residents and fellows ranked this topic as relatively unimportant. Should pediatricians receive training in providing spiritual support to families? And if so, what should physicians learn and understand about providing spiritual support for families?

Many feel that palliative care teams should include sufficient interdisciplinary representation to ensure meeting the medical, psychosocial and spiritual needs of the patient and family.18 Some could argue that physicians may not need education in providing spiritual support since other team members can provide such support. Indeed, some physicians may lack the knowledge and skills to address family members' religious and/or spiritual needs meaningfully, especially if families do not share the physicians' spiritual belief system. However, we believe professionals providing care for dying children should have adequate familiarity with each aspect of palliative care to at least indicate openness to and respect for families' beliefs as all members of the palliative care team may not always be available in times of need.

We worry about trainees ranking emotional support for physicians low on their list of preferred topics of education. Our findings contrast with those from other studies, in which residents expressed the need for additional support.5,14 Possible explanations for our results include: trainees at our institution recognized their need to learn how to cope emotionally, but they simply valued education in this area less than other areas; trainees at our institution feel adequately supported; and/or our trainees might not appreciate the emotional impact that caring for dying children can have. Regardless of the explanation, learning coping skills may improve physicians' comfort with providing end-of-life care and, in turn, improve the quality of the care delivered.

Limitations

As with all surveys, our results are subject to self-reporting and responder bias. We know little about nonresponders. However, with respect to gender, we do know that participants mirrored that of all the eligible residents and fellows. While our survey, like that of Kolarik et al.,14 was not formally validated, practicing pediatric palliative care clinicians reviewed the final survey instrument to ensure inclusion of appropriate topics. In our efforts to make the survey more compact and less specialized we eliminated items related to bowel obstruction and fatigue and did not add items related to other symptoms such as dyspnea and vomiting. Thus we cannot comment on how residents and fellows view education in these areas. Other survey enhancements would allow for the detection of subtle differences that might exist in respondents' views regarding training, knowledge, experience, competency and comfort for a particular area. Additional research could provide respondents the opportunity to comment individually on the educational merits of each palliative care area and each method for learning palliative care.

Future directions

It will be important to evaluate trainee education as programs incorporate formal palliative care teams and to consider implementing education for nonpalliative care attending physicians who treat children with life-limiting conditions and interact with trainees. In addition, a better understanding of what patients and families expect and need from physicians regarding spiritual or other forms of support could help direct educational efforts for physicians.

Conclusions

Pediatric trainees perceive at most moderate levels of training, knowledge, experience, comfort and competence in palliative care. All trainees felt they would benefit from further palliative care education focusing on discussing prognosis, pain control, and delivering bad news. Trainees preferred to learn through observation, bedside teaching, and participation in multidisciplinary groups. The role of physicians in providing spiritual support and the need for physician education in obtaining emotional support for themselves merits further investigation. We suggest that a palliative care team could facilitate palliative care education for both trainees and faculty.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Russ C. Kolarik and his colleagues for sharing their survey. The authors would also like to thank Dr. Elaine Morgan, Dr. David Steinhorn, and Kathleen Blehart for their support of this project.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Himelstein BP. Hilden JM. Boldt AM. Weissman D. Pediatric palliative care. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1752–1762. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra030334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feudtner C. Hays RM. Haynes G. Geyer JR. Neff JM. Koepsell TD. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: National trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107:E99. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hoyert DL. Heron MP. Murphy SL. Kung HC. Deaths: final data for 2003. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2006;54:1–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sack WH. Fritz G. Krener PG. Sprunger L. Death and the pediatric house officer revisited. Pediatrics. 1984;73:676–681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khaneja S. Milrod B. Educational needs among pediatricians regarding caring for terminally ill children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152:909–914. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.9.909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aulino F. Foley K. Professional education in end-of-life care: A US perspective. J R Soc Med. 2001;94:472–476. doi: 10.1177/014107680109400916. ; discussion 477–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sullivan AM. Warren AG. Lakoma MD. Liaw KR. Hwang D. Block SD. End-of-life care in the curriculum: A national study of medical education deans. Acad Med. 2004;79:760–768. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200408000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Field MJ, editor; Behrman RE, editor. Educating Health Care Professionals. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2003. pp. 328–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000;106:351–357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Program requirements for residency education in pediatrics. www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/320pr106.pdf. [Sep 19;2008 ]. www.acgme.org/acWebsite/downloads/RRC_progReq/320pr106.pdf

- 11.Contro N. Larson J. Scofield S. Sourkes B. Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156:14–19. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer EC. Ritholz MD. Burns JP. Truog RD. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: Parents' priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2006;117:649–657. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe J. Grier HE. Klar N. Levin SB. Ellenbogen JM. Salem-Schatz S. Emanuel EJ. Weeks JC. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:326–333. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolarik RC. Walker G. Arnold RM. Pediatric resident education in palliative care: a needs assessment. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1949–1954. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vazirani RM. Slavin SJ. Feldman JD. Longitudinal study of pediatric house officers' attitudes toward death and dying. Crit Care Med. 2000;28:3740–3745. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200011000-00036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehmann EL. Nonparametrics: Statistical Methods Based on Ranks. San Francisco: Holden-Day; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanz RR. Charrow J. Black clouds. Work load, sleep, and resident reputation. Am J Dis Child. 1993;147:579–584. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1993.02160290085032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care. 2004. www.nationalconsensusproject.org. [Sep 19;2008 ]. www.nationalconsensusproject.org [PubMed]