Abstract

Determining free energy surfaces along chosen reaction coordinates is a common and important task in simulating complex systems. Due to the complexity of energy landscapes and the existence of high barriers, one widely pursued objective to develop efficient simulation methods is to achieve uniform sampling among thermodynamic states of interest. In this work, we have demonstrated sampling entropy (SE) as an excellent indicator for uniform sampling as well as for the convergence of free energy simulations. By introducing SE and the concentration theorem into the biasing-potential-updating scheme, we have further improved the adaptivity, robustness, and applicability of our recently developed repository based adaptive umbrella sampling (RBAUS) approach [H. Zheng and Y. Zhang, J. Chem. Phys. 128, 204106 (2008)]. Besides simulations of one dimensional free energy profiles for various systems, the generality and efficiency of this new RBAUS-SE approach have been further demonstrated by determining two dimensional free energy surfaces for the alanine dipeptide in gas phase as well as in water.

INTRODUCTION

Determination of free energy surfaces with computer simulations is of critical importance in quantitatively elucidating many chemical and biological processes, including conformational changes, molecular recognition, and chemical reactions. Besides challenges regarding accuracy of the potential energy surface and its computational efficiency, another key obstacle is to achieve adequate sampling of the configuration space of interest. Due to the complexity of energy landscapes and the existence of high barriers, transitions among distinct thermodynamic states of significance are rare events, which constitute sampling bottlenecks in a straightforward application of molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo simulations. A widely employed strategy to overcome this difficulty is the introduction of an external biasing potential into the Hamiltonian which forces the system to visit the high barrier regions.1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10

An ideal choice of biasing potential would be the negative of the free energy surface so that uniform sampling along chosen reaction coordinates can be achieved. Unfortunately, such information is exactly what we try to obtain from simulations and is not known in the first place. In past years, many adaptive sampling approaches3, 8, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27 have been proposed to overcome this inherent challenge. Among them, very recently we have introduced the repository based adaptive umbrella sampling (RBAUS) method,27 in which a sampling repository is periodically updated based on the latest simulation data, and the accumulated knowledge and sampling history are then employed to determine whether and how to update the biasing umbrella potential to achieve more uniform sampling for subsequent simulations. In comparison with other adaptive sampling methods, such as adaptive umbrella sampling,3, 11, 12, 13, 14 the Wang–Landau approach,15, 16 the adaptive biasing force,17, 18, 28 nonequilibrium metadynamics,8, 19, 20 and self-healing umbrella sampling,24 a unique and attractive feature of the RBAUS method is that the frequency for updating the biasing potential is not predetermined but depends on the sampling history and is adaptively determined on the fly, which smoothly bridges nonequilibrium and equilibrium simulations. Such an adaptive updating is achieved by employing the following general principle: If the subsequent simulations still explore a previously oversampled region more than a previously undervisited one, the biasing potential needs to be updated, otherwise, no updating. Thus we can see that a key element of the RBAUS approach is the determination of sampling uniformity. In addition, a well-defined measure of sampling uniformity can also be used to check the convergence of determined free energy surfaces.

Here, we have introduced the sampling entropy (SE) as a valid indicator for uniform sampling as well as for the convergence of free energy simulations. By introducing SE into the biasing-potential-updating scheme, the adaptivity, robustness, and applicability of the RBAUS approach are significantly improved, including applications to the determination of two-dimensional (2D) free energy surfaces.

THEORY AND METHOD

This section is organized as follows. First we give a brief review of the RBAUS method, then we present the rationale for employing SE and the entropy concentration theorem (ECT) in adaptive sampling, and finally the resulting RBAUS-SE approach is described.

Review of RBAUS

In umbrella sampling2, 24, 27 with a biased Hamiltonian Hb,

| (1) |

and the free energy surface along a set of predefined reaction coordinates η(R) can be computed as

| (2) |

where NS(η) as the number of configurations with given reaction coordinates η in the canonical ensemble generated with the biased Hamiltonian Hb, and c can be any constant. For a given biased ensemble, NS(η) is the raw sampling number of η and K(η)=NS(η)eVb(η)∕kBT can be considered as the corresponding unbiased knowledge of η (Ref. 27) from this biased simulation.

In numerical simulations, it is a common practice to divide reaction coordinates η into Z bins. For the RBAUS approach, the sampling repository stores and updates mainly two kinds of information: the accumulated unbiased knowledge K[i] and the accumulated raw sampling number NS[i] for each bin [i]. K[i] is employed to determine the biasing potential Vb with the following formula:

| (3) |

Meanwhile, NS[i] is used to compute the “histmax-histmin ratio” (HHR), the ratio of its largest value of NS[i] to its lowest value, which is then employed to determine whether to update the biasing potential or not. However, the HHR is not a global uniform sampling indicator and is not defined before all bins are visited. In our original RBAUS approach, several empirical parameters needed to be carefully chosen to result in an efficient heuristic scheme to determine one-dimensional (1D) free energy profiles. Although tests on several very different systems with barriers ranging from 3 to 30 kcal∕mol have been successful, the scheme becomes inefficient when applied to determine 2D free energy surfaces. The problem mainly comes from the inadequacy of HHR as a uniform sampling indicator when the dimension of reaction coordinates and the number of bins increase. Meanwhile, the correlation between HHR and the convergence in determining 1D free energy profiles for those different test systems is quite weak and no general criteria to stop the RBAUS simulations can be suggested. Thus, we are motivated to find a better uniform sampling indicator than HHR so that the robustness, adaptivity, and efficiency of the RBAUS approach can be further significantly improved.

Sampling entropy, concentration theorem, and uniform sampling

Given Z bins along chosen reaction coordinates, the SE (Refs. 29, 30) is defined as

| (4) |

where NS[i] is the number of times that the ith bin has been visited and . We can see that if only one bin is visited, the SE has the minimum value of zero; the SE increases with more bins sampled and it has the maximum value of ln Z if all bins have been equally sampled. Thus the normalized sampling entropy (NSE), NSE=SE∕ln Z, which ranges from 0 to 1, would serve as a general uniform sampling indicator independent of the number of bins. It is dependent on sampling data of all bins and is very well defined even when bins are not sampled. Thus, two main deficiencies of HHR are avoided when using NSE as a uniform sampling indicator.

For complex systems, even with flat free energy surfaces along reaction coordinates of interest, to achieve uniform sampling with MD simulations requires the simulation time to be sufficiently long. At the initial period of simulation, the value of NSE would be expected to be much less than 1 regardless of its underlying free energy landscape. This limitation can be overcome by employing Jayne’s concentration theorem, which states that29 given a number of bins Z with equal probability and N independent sampling points, there is a probability P that the resulting SE(Z,N) should be in the range of

| (5) |

where denotes the critical chi squared for Z−1 degrees of freedom at the 100(1−P) percent significance level. Here the ECT factor is defined as

| (6) |

and provides continuing guidance regarding the expectation value of the SE with the increasing independent sampling number N. This can provide a theoretical basis to decide whether to update the biasing potential in adaptive sampling. Typically, the conventional 5% significance level can be employed, such as and . The quantiles of chi-square distribution can be easily obtained by the function “qchisq” in R language.31

Sampling entropy based RBAUS approach

By employing SE and the concentration theorem in the biasing-potential-updating scheme, the recently developed RBAUS approach has been further improved. The resulting RBAUS-SE simulation scheme is presented in detail in the following steps.

-

(0)

Initial repository setup. Given Z bins along chosen reaction coordinates, set initial values of K[i] and NS[i] for all bins.

-

(1)Biasing-potential update. With the accumulated unbiased knowledge K[i], the free energy profile A[i] is calculated by the following equation:

The biased potential Vb is then obtained based on the negative of the calculated free energy profile. It should be noted that with Eq. 7, A[i] would be zero when K[i] is equal to the average of the accumulated knowledge among all bins—a desired property for constructing the biased potential.(7) -

(2)

Biased simulations. Perform MD simulations with the biased Hamiltonian H0+Vb and collect the raw histogram h[i], which is the number of sampled configurations in each bin.

-

(3)Repository update,

(8)

The updated K[i] would be employed to calculate the current estimation of the free energy profile A[i] through Eq. 7 if desired. At the same time, from the accumulated raw sampling number NS[i], the SE and the ECT factor ECT(Z,N) are calculated with Eqs. 4, 6, respectively. It should be noted that even if free energy surface is flat, sampling among all bins would be far from random in MD simulations. Thus the independent sampling number N in Eq. 6 should be proportional to the total sampling number NStot but needs to be divided by a factor C due to correlations among snapshots in the MD trajectory. In principle, the value of C can be determined by calculating the time correlation function, which would be system dependent. In practice, we found any value between 50 and 200 for C all yields reasonable performance. Thus we have used C to be 100 throughout this work.(9) -

(4)

Make decision on whether to update the biasing potential. If the calculated NSE is larger than 0.99 or the SE is larger than the ECT factor ECT(Z,N), the biasing-potential update is not needed, go to step 2. Otherwise, update is needed, go to step 5.

-

(5)

Repository consolidation. Here the accumulated unbiased knowledge in the sampling repository is consolidated by setting K[i]=K[i]∗[eSE∕eECT(Z,N)] when NSE is less than 0.98. Go to step 1.

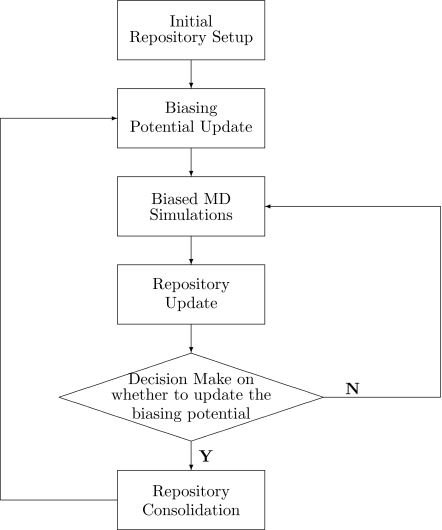

The above scheme is summarized in a flow chart shown in Fig. 1, which keeps the same structure as the original RBAUS approach27 but employs SE in steps 4 and 5. It should be noted that 1.0 is the theoretical NSE value for ideal uniform sampling and the ECT(Z,N) provides guidance regarding the expectation value of the SE with the independent sampling number N. Thus in step 4, when NSE is larger than 0.99 or SE is larger than ECT(Z,N), the current biasing potential can be considered to be good enough and thus no update is needed. In step 5, the employment of eSE∕eECT(Z,N) as the scaling factor rather than a fixed value of 0.618 in the original RBAUS scheme makes the repository consolidation step more adaptive based on the current knowledge about uniform sampling. Overall, the RBAUS-SE approach is more robust and general than the original one, as is further demonstrated by test results below. It should be also noted that embarrassingly parallel simulations can be as easily implemented in the RBAUS-SE method as in the original one.

Figure 1.

The flow chart for the RBAUS approach.

IMPLEMENTATION AND COMPUTATIONAL DETAIL

We have implemented the above presented RBAUS-SE simulation scheme in the TINKER4.2 suite of molecular simulation program.32 The 1D biasing potential is described with the shape-preserving smoothing spline by using Renka’s TSPACK (one-dimension) package,33 and the 2D biasing potential is represented by employing the surface interpolation package SRFPACK (Ref. 34) in conjunction with TRIPACK.35 First we tested the implemented scheme to determine the 1D potential of mean force (PMF) for two systems that we have examined previously:27 One is a simple system that contains two particles interacting with a double well potential having a barrier of 24 kcal∕mol, and the other is the Na+ and Cl− ion pair association in water. For both systems, simulations with four replicas have been carried out, and the repository was updated every 1000 data points collected. To check the convergence of simulations, we calculated the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the simulated PMF with respect to the reference one computed from umbrella sampling,

| (10) |

It should be noted that in these two cases, the distance of two particles r is chosen as the reaction coordinate. Thus the PMF(r) is related to the free energy profile [A(r)] as PMF(r)=A(r)+2kBT ln r. To further demonstrating the applicability and performance of the RBAUS-SE approach, we have used it to determine 2D free energy surfaces of the alanine peptide in gas phase and in aqueous solution as a function of the backbone dihedral angle ϕ and ψ, as illustrated in Fig. 2. This has become a classical example to test enhanced sampling approaches.20, 24, 27, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40

Figure 2.

Schematic of the alanine dipeptide showing the ϕ and ψ angles.

In our simulations, the alanine dipeptide is described by the CHARMM27 force field.41 For the aqueous phase, the simulation of one alanine dipeptide molecule and 245 TIP3P water42 molecules was performed in a cubic box of 19.7429 Å with periodic boundary conditions. The cutoff distance of 9 Å was used for both van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. For the RBAUS-SE simulations, 24 replicas were employed with time steps of 1 fs and temperature of 300 K. The bin width along the reaction coordinates (ϕ and ψ) was set to be 5° and the repository was updated every 1200 collection data points. The reference free energy surfaces for both gas and aqueous phases were calculated from 24 replica equilibrium MD simulations with a fixed biasing potential. Simulations of 6 ns were run for each replica. The biased potential employed for the equilibrium simulations is obtained from the converged RBAUS-SE simulations. In all our test cases, we have assumed no prior knowledge of the system and set all initial K[i] to be 1. The frequencies to collect data were set to be 1, 5, and 2 fs, respectively, for the double well system (each particle has a mass of 1 amu), NaCl, and alanine peptide.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We have applied the RBAUS-SE method to the double well potential model with the barrier of 24 kcal∕mol and the dissociation of a NaCl molecule in water. The results are shown in Figs. 34. Simulation efficiency is found to be very similar to the original RBAUS scheme27 in determining such 1D PMFs, and one attractive advantage of the RBAUS-SE approach is that we can monitor the simulation progress by measuring the NSE. As expected, the error in the simulated PMF decreases with the increase in the NSE. When the NSE first reaches 0.99, the error in the simulated PMF is about 0.1 kcal∕mol for the double well system and 0.2 kcal∕mol for NaCl in aqueous solution, both of which are below 0.5kBT (about 0.3 kcal∕mol when T=300 K). Meanwhile, the plotted normalized ECT (NECT) and NSE curves also illustrate how such information is employed to determine whether to update the biasing potential or not. We can see that for both systems, initially these are nonequilibrium simulations and there is no biasing potential updating after about 65 ps for the double well system and after about 250 ps for the NaCl system (Fig. 34).

Figure 3.

The RMSD, NSE, and NECT factor curves for the double well model system with a barrier of 24 kcal/mol. The circle symbols represent the biasing-potential-updating points.

Figure 4.

The RMSD, NSE, and NECT factor curves for the dissociation of a sodium chloride ion pair in aqueous solution. The circle symbols represent the biasing-potential-updating points.

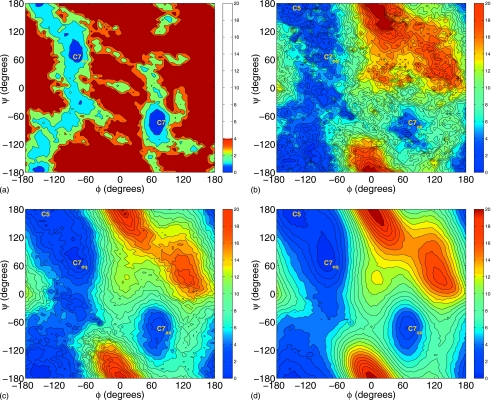

To further demonstrate the robustness, efficiency, and generality of the RBAUS-SE method, we employed it to determine 2D free energy surfaces (FES) of the alanine dipeptide in vacuum and water. Figures 56 illustrate the calculated FES contour maps at different simulation times (10, 50, 100, and 500 ps) for the alanine dipeptide in vacuum and aqueous solution, respectively. In each case, it only takes about 50 ps simulation for each replica to obtain some general features of the 2D free energy surface, and the FES at 500 ps is in excellent agreement with the corresponding reference FES in Fig. 7. The RMSD curves of calculated FES as well as NSE and NECT curves are shown in Figs. 89, which show that with the progress of simulations, the NSE increases and the biasing-potential update stops at about 0.25 ns for both gas phase and aqueous phase. Those figures also indicate that when the NSE first reaches 0.99, the error in calculated FES is a little less than 0.3 kcal∕mol for the alanine dipeptide in vacuum and about 0.2 kcal∕mol for the alanine dipeptide in aqueous solution. These results indicate that the RBAUS-SE approach is an efficient approach to determine converged 2D free energy surfaces.

Figure 5.

Free energy surfaces of the alanine dipeptide system as a function of ϕ and ψ torsional angles in gas phase with 1 kcal/mol contour interval calculated by RBAUS-SE with 24 replica. Upper left: the free energy surface obtained after 10 ps simulation; upper right: the free energy surface obtained after 50 ps simulation; lower left: the free energy surface obtained after 100 ps simulation; lower right: the free energy surface obtained after 500 ps simulation.

Figure 6.

Free energy surfaces of the alanine dipeptide system as a function of ϕ and ψ torsional angles in aqueous phase with 1 kcal/mol contour interval calculated by RBAUS-SE with 24 replica. Upper left: the free energy surface obtained after 10 ps simulation; upper right: the free energy surface obtained after 50 ps simulation; lower left: the free energy surface obtained after 100 ps simulation; lower right: the free energy surface obtained after 500 ps simulation.

Figure 7.

The reference free energy surfaces of the alanine dipeptide system as a function of ϕ and ψ torsional angles in gas phase (left graph) and in aqueous phase (right graph) by biasing equilibrium umbrella sampling for 1 ns with 24 replica.

Figure 8.

The RMSD, NSE, and NECT factor curves for the alanine dipeptide in gas phase. The circle symbols represent the biasing-potential-updating points.

Figure 9.

The RMSD, NSE, and NECT factor curves for the alanine dipeptide in aqueous phase. The circle symbols represent the biasing-potential-updating points.

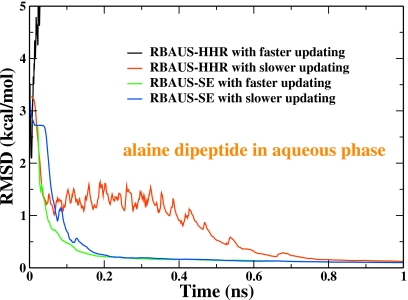

As discussed previously, one main motivation to develop this RBAUS-SE approach is the difficulty of applying the original HHR based RBAUS method27 to determine 2D free energy surfaces. Figures 1011 show the performance of both approaches in determining 2D FES for the alanine dipeptide in gas and aqueous phase respectively. For the original RBAUS-HHR approach, it would not be able to yield meaningful results with the repository updating frequency of every 1200 data points, which is similar to the value employed in previous simulations to determine 1D PMF.27 Although the results can be improved by updating every 12 000 data points, the convergence is quite slow and it still has the difficulty for the alanine dipeptide in gas phase. On the other hand, for the RBAUS-SE approach, the error in the calculated FES becomes less than 0.3 kcal∕mol after 0.25 ns for all four cases, as shown in Figs. 1011. These results clearly indicate that the new RBAUS-SE approach is a much more efficient and robust approach in comparison with the original RBAUS-HHR approach.27

Figure 10.

The RMSD curves for the alanine dipeptide in gas phase with both the original RBAUS-HHR approach and the current RBAUS-SE. The faster updating refers that the repository is updated every 1200 data points, which is similar to the repository updating frequency in previous studies (Ref. 27). The slower updating means that repository is updated every 12 000 data points.

Figure 11.

The RMSD curves for the alanine dipeptide in aqueous phase with both the original RBAUS-HHR approach and the current RBAUS-SE. The faster updating refers that the repository is updated every 1200 data points, which is similar to the repository updating frequency in previous studies (Ref. 27). The slower updating means that repository is updated every 12 000 data points.

Figures 1213 show the correlation between the error in simulated free energy surfaces and the NSE in both RBAUS-SE simulations and equilibrium MD simulations without free energy barriers along reaction coordinates of interest for all four test systems. These results clearly demonstrate that the NSE is an excellent indicator for the convergence of free energy simulations as well as for the uniform sampling. Based on these results, a criteria to stop RBAUS-SE simulations can be suggested, such as NSE=0.993. For all of our four test systems, the error is no more than 0.2 kcal∕mol when NSE=0.993.

Figure 12.

The correlation between the RMSD in simulated free energies and the NSE for all test systems based on RBAUS-SE simulations

Figure 13.

The correlation between the RMSD in simulated free energies and the NSE for all test systems using equilibrium MD calculations with the inverse of the reference free energy surface as the biasing potential.

CONCLUSION

In this work, by employing NSE and the concentration theorem, we have further improved the adaptivity, robustness, and applicability of the RBAUS approach. The tests on alanine peptide in gas phase as well as in water indicate that the RBAUS-SE approach is an efficient approach to determine converged 2D free energy surfaces. Our results clearly demonstrate that the NSE is an excellent indicator for the convergence of free energy simulations as well as for the uniform sampling.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (Grant No. CHE-CAREER-0448156) and the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. R01-GM079223). We appreciate the computational resources and support provided by NYU-ITS.

References

- Chipot C. and Pohorille A., Free Energy Calculations: Theory and Applications in Chemistry and Biology (Springer, New York, 2007). 10.1007/978-3-540-38448-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patey G. N. and Valleau J. P., J. Chem. Phys. 63, 2334 (1975). 10.1063/1.431685 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mezei M., J. Comput. Phys. 68, 237 (1987). 10.1016/0021-9991(87)90054-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roux B., Comput. Phys. Commun. 91, 275 (1995). 10.1016/0010-4655(95)00053-I [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grubmüller H., Phys. Rev. E 52, 2893 (1995). 10.1103/PhysRevE.52.2893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voter A. F., Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 3908 (1997). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.3908 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarzynski C., Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 2690 (1997). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.78.2690 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laio A. and Parrinello M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12562 (2002). 10.1073/pnas.202427399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman J. A. and Tully J. C., J. Chem. Phys. 116, 8750 (2002). 10.1063/1.1469605 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamelberg D., Mongan J., and Mccammon J. A., J. Chem. Phys. 120, 11919 (2004). 10.1063/1.1755656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels C. and Karplus M., J. Comput. Chem. 18, 1450 (1997). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels C., Schaefer M., and Karplus M., J. Chem. Phys. 111, 8048 (1999). 10.1063/1.480139 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rajamani R., Naidoo K. J., and Gao J. L., J. Comput. Chem. 24, 1775 (2003). 10.1002/jcc.10315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Gu Y., and Liu H. Y., J. Chem. Phys. 125, 094907 (2006). 10.1063/1.2346681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo F., Mol. Phys. 100, 3421 (2002). 10.1080/00268970210158632 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang F. G. and Landau D. P., Phys. Rev. E 64, 056101 (2001). 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.056101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Darve E. and Pohorille A., J. Chem. Phys. 115, 9169 (2001). 10.1063/1.1410978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hénin J. and Chipot C., J. Chem. Phys. 121, 2904 (2004). 10.1063/1.1773132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bussi G., Laio A., and Parrinello M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 090601 (2006). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.090601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensing B., De Vivo M., Liu Z. W., Moore P., and Klein M. L., Acc. Chem. Res. 39, 73 (2006). 10.1021/ar040198i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Min D., Liu Y., and Yang W., J. Chem. Phys. 127, 094101 (2007). 10.1063/1.2769356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laio A. and Gervasio F. L., Rep. Prog. Phys. 71, 126601 (2008). 10.1088/0034-4885/71/12/126601 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lelièvre T., Rousset M., and Stoltz G., J. Chem. Phys. 126, 134111 (2007). 10.1063/1.2711185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsili S., Barducci A., Chelli R., Procacci P., and Schettino V., J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 14011 (2006). 10.1021/jp062755j [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barducci A., Bussi G., and Parrinello M., Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 020603 (2008). 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.020603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng L. Q. and Yang W., J. Chem. Phys. 129, 014105 (2008). 10.1063/1.2949815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H. and Zhang Y., J. Chem. Phys. 128, 204106 (2008). 10.1063/1.2920476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darve E., Wilson M. A., and Pohorille A., Mol. Simul. 28, 113 (2002). 10.1080/08927020211975 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaynes E. T., Proc. IEEE 70, 939 (1982). 10.1109/PROC.1982.12425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park S. and Pande V. S., Phys. Rev. E 76, 016703 (2007). 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.016703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R. Development Core Team, R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, http://www.R-project.org 2007).

- Ponder J. W., TINKER, Software Tools for Molecular Design, version 4.2, the most updated version for the TINKER program can be obtained from J. W. Ponder’s worldwide website at http://dasher.wustl.edu/tinker, June 2004.

- Renka R. J., ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 19, 81 (1993). 10.1145/151271.151277 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renka R. J., ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 22, 9 (1996). 10.1145/225545.225547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renka R. J., ACM Trans. Math. Softw. 22, 1 (1996). 10.1145/225545.225546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tobias D. J. and Brooks C. L., J. Phys. Chem. 96, 3864 (1992). 10.1021/j100188a054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. E., J. Chem. Phys. 111, 5568 (1999). 10.1063/1.479860 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosso L., Abrams J. B., and Tuckerman M. E., J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 4162 (2005). 10.1021/jp045399i [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Oliveira C. A. F., Hamelberg D., and Mccammon J. A., J. Chem. Phys. 127, 175105 (2007). 10.1063/1.2794763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolakis J., Ferrara P., and Caflisch A., J. Chem. Phys. 110, 2099 (1999). 10.1063/1.477819 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- A. D.MacKerell, Jr., Bashford D., Bellott M., R. L.Dunbrack, Jr., Evanseck J. D., Field M. J., Fischer S., Gao J., Guo H., Ha S., Joseph-McCarthy D., Kuchnir L., Kuczera K., Lau F. T. K., Mattos C., Michnick S., Ngo T., Nguyen D. T., Prodhom B., W. E.ReiherIII, Roux B., Schlenkrich M., Smith J. C., Stote R., Straub J., Watanabe M., Wiórkiewicz-Kuczera J., Yin D., and Karplus M., J. Phys. Chem. B 102, 3586 (1998). 10.1021/jp973084f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W., and Klein M. L., J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926 (1983). 10.1063/1.445869 [DOI] [Google Scholar]