Abstract

AIM

This study evaluated two strategies to facilitate involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) – a 12-step-based directive approach and a motivational enhancement approach – during skills-focused individual treatment.

DESIGN

Randomized controlled trial with assessments at baseline, end of treatment, and 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after treatment.

PARTICIPANTS, SETTING, and INTERVENTION

169 alcoholic outpatients (57 women) randomly assigned to one of three conditions: a directive approach to facilitating AA, a motivational enhancement approach to facilitating AA, or treatment as usual with no special emphasis on AA.

MEASUREMENTS

Self-report of AA meeting attendance and involvement, alcohol consumption (percent days abstinent, percent days heavy drinking), and negative alcohol consequences.

FINDINGS

Participants exposed to the 12-step directive condition for facilitating AA involvement reported more AA meeting attendance, more evidence of active involvement in AA, and a higher percent days abstinent relative to participants in the treatment-as-usual comparison group. Evidence suggested also that the effect of the directive strategy on abstinent days was partially mediated through AA involvement. The motivational enhancement approach to facilitating AA had no effect on outcome measures.

CONCLUSIONS

These results suggest that treatment providers can use a 12-step-based directive approach to effectively facilitate involvement in AA and thereby improve client outcome.

Keywords: Alcoholics Anonymous, Randomized Controlled Trial, Alcoholism Treatment, Treatment Outcomes, Mediation

Introduction

Effectiveness of Alcoholics Anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) was founded with the goal of helping individuals who suffer from alcoholism. In 2007, there were more than 113,000 AA groups in existence worldwide [1]. In AA's 2007 triennial survey [1] of over 8,000 members from the U.S. and Canada, 33% percent of members reported that they had been sober over 10 years, 12% for 5 to 10 years, and 31% for less than one year. Two meta-analyses [2,3] concluded that a positive relationship exists between AA participation and drinking outcomes. Recent studies also have suggested that AA attendance and participation are associated with improved alcohol outcome [4--14].

Facilitating Involvement in AA

Several researchers have evaluated methods for encouraging AA involvement among patients in alcoholism treatment. Humphreys [15] reviewed three studies in which patients received a 12-step treatment intervention or another intervention (e.g., cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]). In these studies – Project MATCH [16, see also 17], the Department of Veterans Affairs nationwide treatment study [6,18], and McCrady, Epstein, and Hirsch [19, see also 8] – 12-step oriented treatments were found to be more effective than other treatment conditions at promoting patients' affiliation with 12-step self-help groups.

Project MATCH [16] is noteworthy, as the twelve-step facilitation (TSF) therapy developed for use in the study has been carefully manualized and extensively evaluated. Tonigan, Connors, and Miller [17] described AA attendance rates in Project MATCH as a function of the three treatment conditions (TSF, CBT, and motivational enhancement therapy [MET]) in the outpatient sample of alcoholic clients. They found that TSF outpatient clients reported higher AA attendance rates during treatment and during the nine months immediately following treatment, relative to clients in other conditions. On average, TSF clients reported attending AA on approximately 20% of days during treatment (see Figure 11.1, p. 191). Attendance declined to 10% to 15% after the treatment period was completed. A similar pattern was reported for AA-related behaviors. Clients receiving TSF treatment reported more involvement in AA activities, relative to clients in CBT or MET. Again, clients reported an increase during treatment, followed by a decline in AA-related activities post treatment.

Brief intervention approaches

Although research has demonstrated the efficacy of TSF treatment, the practical implications of these findings may be limited. For administrators of existing treatment programs who wish to maintain their programs' current focus (on cognitive-behavioral methods, for example), but nevertheless seek to increase their clients' involvement with 12-step programs, research documenting the efficacy of intensive referrals [e.g., 20,21] or brief additions [22] to existing treatment may have more immediate relevance.

One attempt at developing a brief intervention for facilitating involvement in AA has been reported by Kahler et al. [22]. Forty-eight inpatient detoxification patients were randomized to receive either five minutes of advice to attend AA or a sixty-minute motivational enhancement session [see 23] focusing on increasing 12-step involvement. The two groups did not differ during the 6-month follow-up in terms of AA attendance or alcohol outcomes. However, the motivational intervention was associated with better alcohol outcomes for patients with less 12-step experience, whereas brief advice was associated with better outcomes for patients with more 12-step experience. Greater AA and NA attendance in a given follow-up month was also associated with less alcohol use. This study suggests that a motivational approach may hold some promise, at least among clients with less 12-step experience. Limitations of the study include the relatively small sample size and the absence of a no-facilitation-strategy control group.

Mechanisms of Action

Although there is longitudinal evidence that greater AA attendance and active involvement is associated with reduced drinking [e.g., 5,24], the causal pathways underlying this relationship have been less thoroughly studied. The question remains, are clients more successful because they participate in AA, or does clients' willingness to attend AA result from their motivation and success at maintaining abstinence? Also, if engagement with AA is causally related to increased post treatment abstinence, what mediating mechanisms underlie this effect?

One mechanism that may explain the positive relationship between AA attendance and post treatment abstinence is involvement in AA-related activities such as using a sponsor, working the AA steps, and reading AA literature. To examine this possibility, Humphreys et al. [18], McKeller, Stewart, and Humphreys [25], and Moos et al. [10] analyzed data from a VA sample of 3018 male substance-abusing inpatients attending one of five 12-step, five cognitive-behavioral, or five eclectic (i.e., mixed) treatment programs; patients were not randomized to program type.

At the one-year follow-up, patients in the 12-step and eclectic programs reported more self-help group involvement relative to patients in the cognitive-behavioral programs [18]. Also, patients in the 12-step programs were more likely to be abstinent (45%), relative to patients in the cognitive-behavioral programs (36%) or eclectic programs (40%; [10]). Similarly, patients in the 12-step programs were more likely to be free of substance abuse problems, relative to patients in the other two types of programs [10]. A cross-lagged structural equation model suggested that one-year post treatment AA affiliation predicted lower alcohol problems at the two-year follow-up, but that the reverse path – alcohol problems predicting subsequent AA affiliation – was not significant [25]. Taken together, these findings are consistent with the notion that AA affiliation leads to improved alcohol outcome.

Current Study

The studies reviewed above indicate that AA involvement can be influenced by specific treatment strategies, although the extent to which relatively minor modifications to existing programs can yield improved outcomes remains uncertain. Also, the causal relationship between engagement with AA and reductions in alcohol use is in need of additional study and replication. The purpose of the current study was to examine, in the context of a skills-focused individual treatment program, the efficacy of two strategies to facilitate involvement in AA. The two strategies – a 12-step-based directive approach (DIR) and a motivational enhancement approach (MOT) – were compared to a treatment-as-usual (TAU) condition with no special emphasis on AA involvement. These two strategies were selected for study based on their differing philosophies (i.e., the DIR is more therapist directed versus the MOT which is more client centered). Also, the DIR condition specifically has empirical support, based on the above body of work documenting that 12-step treatments are associated with subsequent AA involvement. Thus, it was hypothesized that participants exposed to either of the two AA-facilitation strategies would have greater Alcoholics Anonymous involvement and improved alcohol outcomes relative to those in the comparison group. Further, it was hypothesized that the effect of facilitation strategies on alcohol outcome would be mediated through AA involvement.

Method

Participants

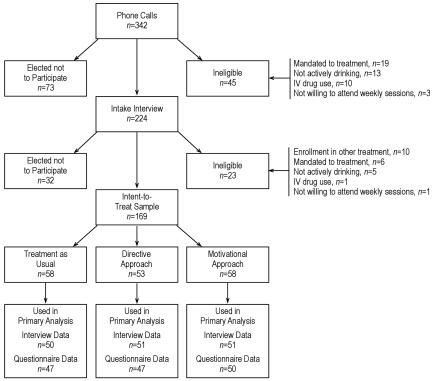

Clients were recruited from the outpatient Clinical Research Center (CRC) at the Research Institute on Addictions in Buffalo, NY, USA. Eligibility criteria were: (a) surpassed 6th grade, (b) no legal or employer mandate for treatment, (c) willing to attend 12 weekly sessions, (d) drinking during the past 3 months, (e) no intravenous drug use in the past three months, and (f) at least 18 years old. Figure 1 depicts the flow of participants through the study protocol. Recruitment was accomplished primarily through newspaper advertisements during January, 2000 through February, 2002.

Figure 1.

Participant flow through the study.

Of 297 eligible callers, 224 presented for an intake interview, ultimately yielding an intent-to-treat sample of 169 individuals. At baseline, 74.0% of the 169 participants provided written consent for the conduct of telephone interviews with a significant other to permit assessment of participants' alcohol use and AA attendance. Characteristics of the intent-to-treat sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics for the sample as a whole and by treatment condition

| Variable | Total (n = 169) |

TAU (n = 58) |

DIR (n = 53) |

MOT (n = 58) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | M or % | SD | |

| Age | 43.8 | (11.0) | 45.2 | (11.8) | 40.8 | (10.9) | 45.3 | (9.9) |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 66.3% | 65.5% | 62.3% | 70.7% | ||||

| Female | 33.7% | 34.5% | 37.7% | 29.3% | ||||

| Marital Status | ||||||||

| Single | 22.5% | 17.2% | 26.4% | 24.1% | ||||

| Married or cohabitating | 48.5% | 44.8% | 49.1% | 51.7% | ||||

| Divorced, separated or widowed | 29.0% | 37.9% | 24.5% | 24.1% | ||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 88.2% | 86.2% | 88.7% | 89.7% | ||||

| Black | 9.5% | 12.1% | 9.4% | 6.9% | ||||

| Other | 2.4% | 1.7% | 1.9% | 3.4% | ||||

| Years of Education | 14.7 | (2.7) | 14.8 | (2.8) | 14.8 | (2.6) | 14.5 | (2.7) |

| Any AA Attendance | 21.9% | 17.2% | 24.5% | 24.1% | ||||

| AA Meetings | 0.7 | (2.5) | 0.6 | (2.5) | 1.0 | (3.0) | 0.6 | (1.8) |

| AA Behaviors | 1.4 | (1.7) | 1.3 | (1.7) | 1.4 | (1.6) | 1.5 | (1.8) |

| AA Steps | 2.6 | (3.9) | 2.5 | (3.7) | 1.9 | (3.2) | 3.2 | (4.5) |

|

| ||||||||

| PDA | 35.4 | (28.9) | 35.7 | (29.0) | 38.8 | (30.2) | 32.1 | (27.6) |

|

| ||||||||

| PDH | 32.7 | (32.1) | 30.8 | (32.4) | 33.0 | (32.6) | 34.4 | (31.9) |

| DrInC | 41.3 | (22.4) | 39.7 | (21.6) | 44.8 | (24.2) | 39.7 | (21.5) |

| Sessions Attended | 6.9 | (4.6) | 7.5 | (4.6) | 7.4 | (4.7) | 5.9 | (4.5) |

| Completed Treatment | 57.4% | 63.8% | 62.3% | 46.6% | ||||

| Participation at 3 months | 89.9% | 86.2% | 96.2% | 87.9% | ||||

| Participation at 6 months | 87.0% | 86.2% | 90.6% | 84.5% | ||||

| Participation at 9 months | 84.0% | 81.0% | 88.7% | 82.8% | ||||

| Participation at 12 months | 82.2% | 75.9% | 88.7% | 82.8% | ||||

Notes. TAU = Treatment as usual comparison condition; DIR = directive AA facilitation condition; MOT = motivational AA facilitation condition. Any AA Attendance = proportion of participants who attended at least one AA meeting during the six-month baseline period. AA Meetings = the number of meetings per month during the six-month baseline period. AA Behaviors and AA Steps are from the Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement questionnaire at baseline and represent lifetime scores. PDA = percent days abstinent during the six-month baseline period. PDH = percent days of heavy (greater than six standard drinks) drinking during the six-month baseline period. DrInC = Drinker Inventory of Consequences total score for the six-month baseline. Sessions Attended = number of treatment sessions attended out of a possible 12. Completed Treatment = proportion who completed at least 6 of the 12 total treatment sessions. Participation at the various time points reflects the proportion who completed the Timeline Follow-Back interview (from which AA meeting attendance, PDA, and PDH were drawn) at that assessment wave.

Treatment

All clients received a 12-session, manualized skills-based treatment package, partially adapted from Monti, Abrams, Kadden, and Cooney [26], that included topics such as problem-solving skills, drink refusal, and relaxation skills. The first session was 90 minutes; remaining sessions were 60 minutes. Beginning in Session 2 and throughout the remainder of treatment, all clients were given the weekly instruction to “attend at least a couple of AA meetings each week.” What differed among conditions were the manner in which the therapist discussed AA involvement and the extent and content of AA material covered during sessions (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Session Content by Treatment Condition

| Session | TAU | DIR | MOT |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Psychosocial Assessment | Psychosocial Assessment | Psychosocial Assessment |

| 2 | Final Treatment Plan Intro to AA Skills: Problem Solving |

Final Treatment Plan Intro to AA (readings, attendance slips, journal contract) Acceptance of Disease of Alcoholism |

Final Treatment Plan Intro to AA (handout, cost/ benefit) AA Discussion |

| 3* | Significant Other (support focus) |

Surrender Skills: Problem Solving |

AA Decision Skills: Problem Solving |

| 4 | Skills: Drink Refusal | Significant Other (Al-Anon focus) | Significant Other (support focus) |

| 5 | Monitoring Client Progress | Skills: Drink Refusal | Skills: Drink Refusal |

| 6 | Skills: Relaxation | Skills: Relaxation | Skills: Relaxation |

| 7 | Mid-Way Evaluation of Treatment Goals | Mid-Way Evaluation of Treatment Goals (Getting Active) | Mid-Way Evaluation of Treatment Goals |

| 8 | Skills: Communication | Skills: Communication | Skills: Communication |

| 9 | Skills: Anger Management | Skills: Anger Management | Skills: Anger Management |

| 10 | Coping, Relapse Prevention | Coping, Relapse Prevention | Coping, Relapse Prevention |

| 11 | Monitoring Client Progress | Monitoring Client Progress | Monitoring Client Progress |

| 12 | Termination | Termination | Termination |

Notes.

Beginning with Session 3, a condition-specific review of AA occurred at the beginning of each session.

Highlighted material designates condition-specific treatment content.

TAU = Treatment as usual comparison condition; DIR = directive AA facilitation condition; MOT = motivational AA facilitation condition.

In the DIR condition, when discussing AA, therapists used a therapist-directed AA facilitation style consistent with the Project MATCH twelve-step facilitation therapy [see 27]. In Session 2 the therapist and client discussed Step 1 of AA, and the therapist instructed the client to attend “at least a couple of meetings each week,” with the tradition of “90 meetings in 90 days” also mentioned. The client signed a contract describing the client's goal of attending weekly meetings. Also, the client was encouraged to keep a journal of meetings attended, and was provided with the AA “Big Book” [28] and Living Sober [29]. In Session 3, the discussion of AA-related material focused on AA Steps 2 and 3 and on the fellowship of AA. Session 4, the significant other session, was focused on the significant other's involvement in Al-Anon. In Session 7, the therapist and client discussed the concept of “getting active:” participating in meetings, receiving support from other AA members, and using a sponsor. Overall, approximately 38% of material delivered during the 12 sessions had an AA focus; the remainder of the material was skills based.

In the MOT condition, when discussing AA, a motivational enhancement approach to encouraging AA attendance and participation was employed. This approach was designed to incorporate the principles and methods of motivational interviewing [23]. Specifically, in Session 2, the therapist elicited from the client his or her thoughts about, attitudes toward, and prior experiences with AA. After reflecting this information back to the client, the therapist provided a brief overview of the positive aspects of AA, aspects that are sometimes identified as negative, and a summary of points that address common objections to AA. Finally, the therapist stated that “although you may likely benefit from attending at least a couple of AA meetings each week, ultimately it is up to you to determine your own level of involvement.” In Session 3, the therapist helped the client gauge the relative strength and importance of the costs and benefits of AA and attempted to facilitate a decision in favor of attending AA. Overall, approximately 20% of treatment material had an AA motivational focus.

In the TAU condition, clients received the standard instruction to “attend at least a couple of AA meetings each week.” In subsequent sessions, in conjunction with reviewing how clients were functioning, the therapist briefly asked about AA attendance. When clients reported attendance, the therapist stated, “good; AA is an important component of your treatment. You should continue to attend at least a couple of AA meetings each week.” Overall, approximately 8% of treatment material had an AA focus.

All six therapists were trained together in the skills-based treatment. Therapists then were trained in pairs (by condition) to use one of the three approaches to discussing AA. Ongoing supervision was condition-specific and included review of session audiotapes.

Random assignment to condition was conducted by the third author via urn randomization [30,31] to balance lifetime Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement [32] scores across conditions.

Clients attended an average of 6.9 (SD = 4.6) of the 12 possible sessions. There were no significant differences among experimental conditions.

Assessments

At baseline, treatment end, and 6 and 12 months after the end of treatment, the client completed an in-person assessment that included a questionnaire packet and an interview. At 3 and 9 months after the end of treatment, the interview was conducted with the client over the phone. Collateral interviews occurred via phone at baseline, end of treatment, and at 3, 6, 9, and 12 months following treatment end. Research interviewers were blind to intervention condition.

AA participation

The Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB) interview [33] was used to assess AA meeting attendance. At baseline, the client reported the presence or absence of attendance at AA for each day of the previous six month period. Following treatment, this interview was administered at the end of treatment and at the end of each of the four follow-up periods (3-, 6-, 9-, and 12-month follow-ups). The average number of days of AA meeting attendance per month (AA Meetings) during the previous three months, or, for the previous six months in the case of the baseline interview, was calculated.

The Alcoholics Anonymous Involvement questionnaire [32] was administered at baseline, end of treatment, and at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups. Two variables were calculated from this questionnaire. First, an AA Behaviors scale score was derived from the sum of the presence (= 1) or absence (= 0) of six behaviors: attendance at a meeting, considering self to be a member of AA, going to “90 meetings in 90 days” (i.e., daily sobriety meetings), celebrating an AA sobriety birthday, having an AA sponsor, and being an AA sponsor. A second variable was calculated based on the count of the number of AA Steps “worked.” At baseline, these questions were asked from a lifetime perspective. At treatment end, the questions were asked for the treatment period; at 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments, they were asked for the previous six months. Reliability of the scale is acceptable [32].

Alcohol use and consequences

The TLFB interview was used to gather daily drinking data from the participant and collateral. Days were coded as abstinent, light (one to three standard drinks), moderate (four to six standard drinks), or heavy (more than six standard drinks) drinking. Percent days abstinent (PDA) and the percent days of heavy drinking (PDH) were calculated for the 6-month baseline period, the treatment period, and the four quarterly follow-up periods; each quarterly follow-up time point represents the average percentage of days abstinent (or heavy drinking) during the previous three months.

The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC, [34]) was used to assess a wide range of negative effects of alcohol use. Frequency of occurrence of each of 45 negative consequences was assessed for occurrence during the previous 6 months (at baseline and at 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments). For each item, response choices ranged from “never” (0) to “daily or almost daily” (3). Responses were summed to calculate a total score. Psychometrics of the scale are acceptable [34].

Data Analytic Strategy

Effects of AA facilitation on outcome

Repeated measures analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) with planned contrasts evaluated the hypotheses that participants in the DIR and MOT conditions would show greater involvement in AA and lesser involvement with alcohol relative to those in the TAU condition. To test these hypotheses, we subjected post-treatment assessments of each outcome measure to an ANCOVA in which the baseline score served as the covariate. We used a restricted maximum likelihood approach to estimate model parameters using Proc Mixed in SAS/STAT 9 [35]. Within the ANCOVAs, planned comparisons separately examining the effects of DIR (versus TAU; i.e., the “DIR contrast”) and MOT (versus TAU; i.e., the “MOT contrast”) provided the key omnibus tests of hypotheses. Linear, and when possible, quadratic and cubic effects of time were examined as main effects and in interaction with the experimental condition contrasts.

Mediation of the treatment condition effect on percent days abstinent

Maximum likelihood estimation, using AMOS software, version 6 [36], was used to test a model in which the treatment condition had direct effects on both PDA and AA involvement, which in turn predicted subsequent waves of PDA and AA involvement in a cross-lagged panel design. Imputation of missing data was performed using the expectation maximization algorithm in SPSS 15.0 [37]. Cases were included only if participants had completed at least one post treatment TLFB wave. Using this rule left 154 cases in the dataset.

Model fit was assessed using chi square, the comparative fit index (CFI), the normed fit index (NFI), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). CFI and NFI values of greater than 0.95 indicate “superior” model fit; RMSEA values of less than .08 indicate “reasonable” errors of approximation [38].

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Transformations

Outcome variables evidencing significant deviations from normality were transformed using arc sine (PDA, PDH), inverse (AA Meetings), or square root (DrInC) transformations.

Participant – collateral agreement

All correlations between participant and collateral reports were significant (ps < .01). For AA Meetings, correlations ranged from .61 to .81. For PDA, correlations ranged from .60 to .81. For PDH, correlations ranged from .25 to .52. Client and collateral reports were not significantly different for 13 of 15 comparisons; collaterals reported significantly greater PDH drinking relative to participants at 9- and 12-month follow-up assessments (ps < .05).

Effects of AA Facilitation Condition on Outcome

Repeated measures ANCOVAs with planned contrasts were performed to evaluate the DIR and MOT condition effects on AA-related outcomes and alcohol involvement outcomes.

AA-related outcomes

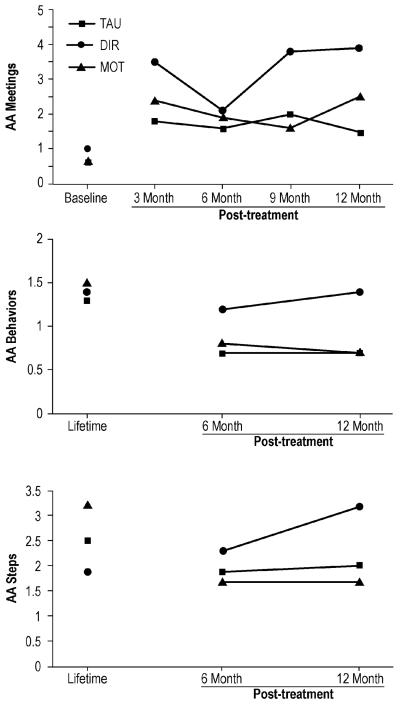

Three dependent variables were evaluated via repeated measures ANCOVAs -- AA Meetings, AA Behaviors and AA steps. Raw means are displayed in Figure 2. For AA Meetings, a DIR contrast main effect, F(1, 148) = 4.75, p < .05, was modified by a DIR contrast interaction with the quadratic component of time, F(1,419) = 6.45, p < .05. Significant simple contrast effects were revealed at the 3-month, 9-month, and 12-month follow-up points, Fs(1, 419) = 4.17, 7.31, and 4.70, ps < .05, .01, and .05, respectively, each indicating greater AA meeting attendance among participants in the DIR condition relative to participants in the TAU condition. Consistent with hypotheses, participants who received the DIR facilitation strategy reported attending more AA meetings during these follow-up windows than did participants in the TAU condition.

Figure 2.

Raw means for baseline (AA Meetings) or lifetime scores (AA Behaviors, AA Steps) and follow-up assessments for Alcoholics Anonymous variables as a function of treatment condition.

For the AA Behaviors scale, a significant DIR contrast main effect, F(1, 133) = 5.76, p < .05, was modified by an interaction with the linear component of time, F(1, 115) = 5.15, p < .05. A significant simple contrast effect at the 12-month assessment point, F(1, 115) = 7.05, p < .01, indicated that participants in the DIR condition reported more AA-related behaviors during the last six months of follow-up than did participants in the TAU condition.

For AA “steps worked,” a significant interaction between DIR and the linear component of time was found, F(1, 115) = 4.16, p < .05. A significant simple contrast effect was revealed for the 12-month follow-up point, F(1, 115) = 4.17, p < .05, which indicated that participants in the DIR condition reported more AA steps worked during the last six months of follow-up relative to participants in the TAU condition.

The main effects of time, the MOT contrasts and MOT by time component interactions were not significant for any of the three AA-related outcomes.

Alcohol involvement outcomes

Three alcohol involvement dependent variables were evaluated -- PDA, PDH, and the DrInC. Raw means are displayed in Figure 3. For PDA, a significant quadratic main effect of time was present, F(1, 419) = 5.15, p < .05. A significant DIR contrast main effect for PDA, F(1, 148) = 4.30, p < .05, was modified by an interaction with the quadratic component of time, F(1, 419) = 7.89, p < .01. Significant simple contrast effects were revealed for the 6-month and 12-month follow-up points, Fs(1, 419) = 5.47 and 4.98, both ps < .05. Consistent with our hypotheses, participants who received the DIR facilitation strategy reported more abstinent days during these follow-up windows than did participants in the TAU condition. The MOT contrast and MOT by time interactions were not significant in this analysis.

Figure 3.

Raw means for baseline and follow-up assessments for drinking outcomes as a function of treatment condition.

Neither PDH nor DrInC scores yielded significant main effects for time or treatment condition contrasts as either main effects or in interaction with time, indicating no effect of either AA facilitation strategy for these dependent variables.

Mediation of the Treatment Condition Effect on Percent Days Abstinent

As reported above, the directive AA facilitation condition led to relatively greater increases in both abstinence and AA involvement. We next undertook analyses to evaluate the hypothesis that AA involvement mediated the relationship between treatment condition and PDA.

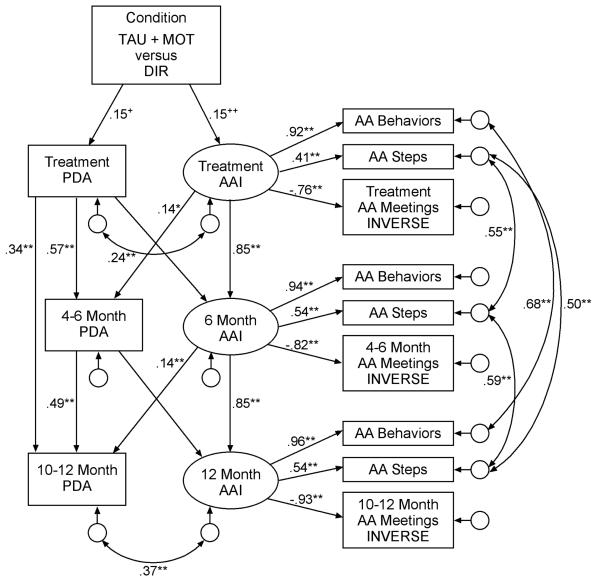

Alcoholics Anonymous involvement as a mediator

Figure 4 displays the model examining Alcoholics Anonymous involvement (AAI) as a mediator in the relationship between treatment condition (TAU and MOT combined versus DIR; dummy coded as 0 and 1, respectively) and outcome PDA. Involvement in AA was represented as a latent construct, using three indicators: AA Behaviors scale scores, the number of steps “worked,” and AA Meetings during the previous three months. Three waves of data were modeled: the end-of-treatment assessment, the 6-month follow-up, and the 12-month follow-up. During model development, review of modification indices suggested the addition of four covariances among error terms between assessment waves, a direct path between during-treatment PDA to 10-12 month PDA, and the addition of two correlations between residual terms within assessment waves.

Figure 4.

Mediation analysis examining the indirect effect of Alcoholics Anonymous involvement in the relationship between the directive facilitation strategy and percent days abstinent. Standardized regression weights are presented. +p < .06, ++p < .10, *p < .05, **p < .01. Paths that are drawn but have no coefficients were included in the model, but not significant. The AA Meetings variable underwent an inverse transformation, thus reversing the direction of the variable. TAU + MOT versus DIR = the combined treatment as usual and motivational enhancement approach conditions versus the directive strategy condition; PDA = percent days abstinent (arc sine transformed); AA = Alcoholics Anonymous; AAI = Alcoholics Anonymous involvement; 4-6 Month = behavior occurring between four and six months after treatment end; 10-12 Month = behavior occurring between 10 and 12 months after treatment end.

Inspection of Figure 4 indicates that the directive approach to facilitating AA had a near-significant (p < .06) positive direct effect on PDA during treatment. The directive approach also had a near-significant (p < .10) positive direct effect on the mediator -- AAI -- during treatment. These effects were consistent with the significant effects identified in outcome analyses. In terms of the cross-lagged portion of the model, the AAI construct at the end of treatment and at 6-month follow-up had significant direct effects on subsequent PDA. In contrast, PDA had no significant direct effects on subsequent AAI. This pattern of findings is consistent with the existence of a mediated pathway from the directive AA facilitation approach, through involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous, to the percent days abstinent dependent measure. Although the chi square test for the model was significant, χ2(52) = 83.7, p < .01, fit indices indicated good model fit to the data, NFI = .940, CFI = .976, RMSEA = .063.

Discussion

This study examined a 12-step-based directive strategy and a motivational enhancement strategy for facilitating involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous. Each strategy was implemented in the context of a 12-session skills-based outpatient alcoholism treatment protocol. As hypothesized, participants exposed to the 12-step directive strategy for facilitating AA involvement reported more active involvement in AA and greater abstinence during portions of the year following treatment, relative to participants in the treatment-as-usual comparison group. Further, SEM indicated that the effect of the DIR treatment on subsequent PDA was partially mediated through AA involvement.

The DIR facilitation condition was successful in increasing AA attendance beyond the level found in the TAU clients. For instance, clients in the DIR condition attended an average of 3.5 meetings per month during the first three months post treatment. This level of AA attendance is similar to that found during the follow-up to the Project MATCH treatments. In that study, for the full sample, AA attendance was, on average, “slightly higher than once every ten days during the follow-up phase of the study” (i.e., approximately 3 meetings per month) ([12]; p. 71). For the Project MATCH outpatient TSF condition specifically, AA attendance ranged from 10% to 15% of days during follow-up (i.e., between 3 and 4.5 meetings per month) ([17]; Figure 11.1, p. 191).

During follow-up, participants in the current study's DIR condition also reported 1.2 AA-related behaviors during the first six months following treatment, out of a possible six behaviors. This figure is comparable to the number of AA involvement behaviors reported by clients in the Project MATCH outpatient TSF condition; at the assessment point six months following treatment, patients in that study reported an average of 2.5 behaviors (out of a possible 13) ([17]; Table 11.1, p. 194).

In addition to increased involvement in AA, as hypothesized, participants receiving the DIR facilitation strategy also reported a greater percent days abstinent during follow-up, relative to TAU participants. Averaged across the follow-up year, the DIR participants reported about 80 percent days abstinent, relative to only about 65 percent days abstinent for participants in the TAU condition. This is a compelling finding, as the DIR condition did not differ from the TAU condition in terms of skills-based treatment material – the two conditions differed only in the extent and nature of AA-related material that was presented and discussed.

One potential mediator of the relationship between treatment condition and percent days abstinent during follow-up is AA involvement. A structural equation model demonstrating a p < .10 direct effect of treatment condition (TAU + MOT versus DIR in this analysis) on AA involvement during treatment, and significant direct effects of AA involvement during treatment and at six months follow-up on subsequent waves of percent days abstinent, yielded support for this hypothesis. Specifically, the standardized total effect of treatment condition on percent days abstinent at 10 to 12 months following treatment was β = .122; 23% of this effect was mediated through AA involvement. Similarly, the standardized total effect of treatment condition on percent days abstinent at four to six months following treatment was β = .108; 19% of this effect was mediated through AA involvement. Of note, the reverse paths, from percent days abstinent to subsequent AA involvement, were not significant. This pattern of findings suggests that, consistent with the findings of McKellar, et al. [25], the association between abstinent outcome and AA involvement is unidirectional: from AA involvement to abstinence.

A p < .06 direct effect of treatment condition on percent days abstinent during treatment also was found. One possible interpretation of this direct path is that the DIR condition, in which therapists briefly discussed such topics as surrender and powerlessness and suggested readings from AA literature, contributed to an increase in awareness of the importance of abstinence among clients in that condition, relative to those in the TAU and MOT conditions.

Use of a motivational enhancement approach to facilitating AA did not have the hypothesized impact on AA-related variables and alcohol involvement measures. There are several possible reasons for this null finding. First, previous indications in the literature [e.g., 15] suggest that the treatments most effective at involving clients in 12-step programs reflect an overall treatment philosophy that is consistent with the 12-step model. The apparent mismatch between the philosophy guiding the motivational enhancement approach and that guiding the 12-step model may have contributed to making the motivational enhancement approach ineffective in facilitating AA involvement. For example, the motivational enhancement approach, although guiding participants towards AA involvement, was client-centered, and therapists did not take an overtly directive approach to promoting AA involvement as therapists did in the DIR condition.

Another possible interpretation for the failure to find an effect for the motivational enhancement approach is that it provided less direct exposure to AA-related concepts, relative to the directive approach. Specifically, during session 2, participants in the motivational enhancement approach received a two-page handout covering the strengths of AA and addressing common concerns about going to AA, with relevant therapist discussion. Although clients were asked to complete an AA cost/benefit worksheet as homework to session 2, this exercise did not provide the client with AA information or material (e.g., regarding AA Steps or readings). In contrast, in early sessions of the directive approach, therapists presented specific AA-related material by briefly discussing Steps 1, 2 and 3 (powerlessness, higher power, and surrender) and providing the AA “Big Book” and Living Sober. Indeed, the total percentage of AA-related material presented in this condition was almost twice what was presented in the MOT condition. This lack of exposure to AA principles in the MOT condition may have been insufficient to create knowledge-based “comfort” with or understanding of AA; these were more likely to be obtained in the directive condition, leading to increased AA attendance.

Our findings should be viewed with several limitations in mind. First, these results do not directly address the question of the efficacy of AA. Although we randomly assigned clients to facilitation condition, we did not randomly assign clients to attend or not attend AA; this randomization would be necessary to test the efficacy of AA attendance. We do, however, present evidence that AA involvement predicts subsequent abstinence, and that the reverse path – abstinence predicting subsequent AA involvement – is not consistent with our data.

A second limitation of the present research is the lack of objective verification (e.g., coded session audiotapes) that the motivational enhancement methods were implemented in a consistent and effective manner. However, the therapists received extensive training and ongoing supervision, which provided us with substantial assurance that the motivational enhancement methods were being applied effectively and appropriately.

Finally, the sample was primarily comprised of White clients (88%), and clients who were mandated to treatment were excluded from participation in the study. Thus, caution should be used in generalizing present results to populations of other ethnic and racial backgrounds and to clients who are mandated to treatment.

Conclusion

In summary, treatment employing an AA facilitation strategy that was strongly therapist-directed resulted in more AA meetings attended, more active AA involvement, and more abstinent days during portions of the year following treatment, relative to treatment that placed no special emphasis on AA. Further, modeling indicated that the effect of this therapist-directed AA facilitation treatment condition on improved abstinent days was partially mediated through AA involvement. Finally, evidence suggested that incorporating AA-related material into a skills-based treatment may also have a direct effect on treatment efficacy. These results suggest that treatment providers can effectively and productively facilitate involvement in AA, even in the context of treatment programs such as CBT that are not primarily 12-step focused.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH grant AA11529. Portions of these data were presented at the June, 2004 annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada. We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of staff: Darlene Cutonilli, Mark Duerr, Sam Gonzalez, Kathy Johnson, Dawn Keough, Dawn Mach, Carol Nottingham, Eugenia Riollano, Kathy Skibicki, and Jason Welborn. Finally, we appreciate Isaac Dompreh's statistical assistance and Robert Marczynski's graphics assistance.

References

- 1.Alcoholics Anonymous . Alcoholics Anonymous: 2007 Membership Survey. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services, Inc.; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kownacki RJ, Shadish WR. Does Alcoholics Anonymous work: The results from a meta-analysis of controlled experiments. Subst Use Misuse. 1999;34:1897–1916. doi: 10.3109/10826089909039431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tonigan JS, Toscova R, Miller WR. Meta-analysis of the literature on Alcoholics Anonymous: Sample and study characteristics moderate findings. J Stud Alcohol. 1996;57:65–72. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connors GJ, Tonigan JS, Miller WR. A longitudinal model of intake symptomatology, AA participation and outcome: Retrospective study of the Project MATCH outpatient and aftercare samples. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:817–825. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gossop M, Stewart D, Marsden J. Attendance at Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, frequency of attendance and substance use outcomes after residential treatment for drug dependence: A 5-year follow-up study. Addiction. 2007;103:119–125. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Humphreys K, Moos RH. Encouraging posttreatment self-help group involvement to reduce demand for continuing care services: Two-year clinical and utilization outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:64–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00273.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaskutas LA, Amon L, Delucchi K, Room R, Bond J, Weisner C. Alcoholics Anonymous careers: Patterns of AA involvement five years after treatment entry. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1983–1989. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000187156.88588.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Kahler CW. Alcoholics Anonymous and relapse prevention as maintenance strategies after conjoint behavioral alcohol treatment for men: 18-month outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:870–878. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKellar J, Stewart E, Humphreys K. Alcoholics Anonymous involvement and positive alcohol-related outcomes: Cause, consequences or just a correlate? A prospective 2-year study of 2,319 alcohol-dependent men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:302–308. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moos RH, Finney JW, Ouimette PC, Suchinsky RT. A comparative evaluation of substance abuse treatment: I. Treatment orientation, amount of care, and 1-year outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:529–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moos RH, Moos BS. Paths of entry into Alcoholics Anonymous: Consequences for participation and remission. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1858–1868. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000183006.76551.5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonigan JS. Benefits of Alcoholics Anonymous attendance: Replication of findings between clinical research sites in Project MATCH. Alcohol Treat Q. 2001;19:67–77. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonigan JS, Miller WR, Connors GJ. Project MATCH client impressions about Alcoholics Anonymous: Measurement issues and relationship to treatment outcome. Alcohol Treat Q. 2000;18:25–41. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weiss RD, Griffin ML, Gallop RJ, Najavits LM, Frank A, Crits-Christoph P, Thase ME, Blaine J, Gastfriend DR, Daley D, Luborsky L. The effect of 12-step self-help group attendance and participation on drug use outcomes among cocaine-dependent patients. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Humphreys K. Professional interventions that facilitate 12-step self-help group involvement. Alcohol Res Health. 1999;23:93–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Project MATCH Research Group Matching alcoholism treatments to client heterogeneity: Project MATCH three-year drinking outcomes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1300–1311. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tonigan JS, Connors GJ, Miller WR. Participation and involvement in Alcoholics Anonymous. In: Babor T, Del Boca F, editors. Treatment matching in alcoholism. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 2003. pp. 184–204. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Humphreys K, Huebsch PD, Finney JW, Moos RH. A comparative evaluation of substance abuse treatment: V. Substance abuse treatment can enhance the effectiveness of self-help groups. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:558–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCrady BS, Epstein EE, Hirsch LS. Maintaining change after conjoint behavioral alcohol treatment for men: Outcomes at six months. Addiction. 1999;94:1381–1396. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.949138110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timko C, DeBenedetti A. A randomized controlled trial of intensive referral to 12-step self-help groups: One-year outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;90:270–279. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timko C, DeBenedetti A, Billow R. Intensive referral to 12-step self-help groups and 6-month substance use disorder outcomes. Addiction. 2006;101:678–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kahler CW, Read JP, Stuart GL, Ramsey SE, McCrady BS, Brown RA. Motivational enhancement for 12-step involvement among patients undergoing alcohol detoxification. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:736–741. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.4.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2nd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelly JF, Stout R, Zywiak W, Schneider R. A 3-year study of addiction mutual-help group participation following intensive outpatient treatment. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1381–1392. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McKellar J, Stewart E, Humphreys K. Alcoholics Anonymous involvement and positive alcohol-related outcomes: Cause, consequence, or just a correlate? A prospective 2-year study of 2,319 alcohol-dependent men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71:302–308. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monti PM, Abrams DB, Kadden RM, Cooney NL. Treating alcohol dependence: A coping skills training guide. Guilford Press; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nowinski J, Baker S, Carroll K. Twelve step facilitation therapy manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; Rockville, MD: 1995. (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Project MATCH Monograph Series Vol. 1). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Alcoholics Anonymous . Alcoholics Anonymous. 4th Ed. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; New York: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alcoholics Anonymous . Living Sober: Some methods A.A. members have used for not drinking. Alcoholics Anonymous World Services; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stout RL, Wirtz PW, Carbonari JP, Del Boca FK. Ensuring balanced distribution of prognostic factors in treatment outcome research. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;(Suppl 12):70–75. doi: 10.15288/jsas.1994.s12.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wei LJ. An application of an urn model to the design of sequential controlled trials. J Am Stat Assoc. 1978;73:559–563. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tonigan JS, Connors GJ, Miller WR. Alcoholics Anonymous involvement (AAI) scale: Reliability and norms. Psychol Addict Behav. 1996;10:75–80. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten R, editors. Techniques to assess alcohol consumption. Humana Press; New Jersey: 1992. pp. 41–72. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller WR, Tonigan S, Longabaugh R. The Drinker Inventory of Consequences (DrInC): An instrument for assessing adverse consequences of alcohol abuse. Government Printing Office; Washington DC: 1995. (NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series, Vol. 4). [Google Scholar]

- 35.SAS Institute Inc. SAS/STAT 9 [Computer Software] SAS Institute Inc; Cary, NC: 2002-2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arbuckle JL. Amos 6.0 [Computer Software] Amos Development Corporation; Spring House, PA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 37.SPSS, Inc. SPSS 15 [Computer Software] SPSS, Inc.; Chicago, IL: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. [Google Scholar]