Abstract

Background

There is a growing appreciation of the role that nasal mucosa plays in innate immunity. In this study, the expression of pattern recognition receptors known as toll-like receptors (TLRs) and the effector molecules complement factor 3 (C3), properdin, and serum amyloid A (SAA) were examined in human sinonasal mucosa obtained from control subjects and patients with chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS).

Methods

Sinonasal mucosal specimens were obtained from 20 patients with CRS and 5 control subjects. Messenger RNA (mRNA) was isolated and tested using Taqman real-time polymerase chain reaction with primer and probe sets for C3, complement factor P, and SAA. Standard polymerase chain reaction was performed for the 10 known TLRs. Immunohistochemistry was performed on the microscopic sections using antibodies against C3

Results

Analysis of the sinonasal sample mRNA revealed expression of all 10 TLRs in both CRS samples and in control specimens. Expression of the three effector proteins was detected also, with the levels of mRNA for C3 generally greater than SAA and properdin in CRS patients. No significant differences were found in TLR or innate immune protein expression in normal controls. Immunohistochemical analysis of sinonasal mucosal specimens established C3 staining ranging from 20 to 85% of the epithelium present.

Conclusion

These studies indicate that sinonasal mucosa expresses genes involved in innate immunity including the TLRs and proteins involved in complement activation. We hypothesize that local production of complement and acute phase proteins by airway epithelium on stimulation of innate immune receptors may play an important role in host defense in the airway and, potentially, in the pathogenesis of CRS.

The sinonasal mucosa has an important function as a first line of immune defense for the respiratory system. Many mechanisms have evolved to protect the host from the airborne irritants, organisms, and particulate material that enter the nasal cavity during the act of breathing. The principal protective factor is the mucus blanket, which entraps particulate material and is constantly removed to the nasopharynx through the process of mucociliary clearance. Contained within the mucus are a variety of secreted factors, such as lysozyme and lactoferrin, that assist in destroying or inhibiting the growth of microorganisms.1,2 Other soluble components, such as mannose-binding lectin or complement, bind to potential pathogens and opsonize them for attack by patrolling phagocytes and granulocytic leukocytes. These broadly acting and nonspecific processes are referred to as innate immunity. This term is to be contrasted with adaptive, or acquired, immunity, wherein antigens are processed and presented to lymphocytes, which in turn direct highly specific immune effector cell responses. In the normal function of the nose and sinuses, both the innate and the adaptive immune systems act in concert to maintain homeostasis and coordinate host defense. Although not typically considered immune cells, sinonasal epithelial cells are, by virtue of their superficial location, likely to participate in both arms of the immune system. However, the function of the epithelium in this regard remains unclear, and, in particular, the relationship between epithelial immune activity and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is largely unstudied.

In CRS, a prolonged and exaggerated inflammatory state is perpetuated often without an identifiable trigger. The type of inflammation in polypoid CRS generally is eosinophilic and characterized by a Th2 cytokine profile.3–6 Although the activated lymphocyte population largely determines the Th2 response, there are multiple sources of the proinflammatory mediators produced in CRS, including epithelial cells.7 Many factors that are responsible for driving epithelial expression of cytokines in CRS originate from mucosal or submucosal lymphocytes and thus are manifestations of adaptive immune responses. However, epithelial cells also can be stimulated to express inflammatory mediators by extramucosal factors encountered at their luminal surfaces.8,9 In the recent literature, pattern-recognition receptors, known as toll-like receptors (TLRs), have been demonstrated in airway and gastrointestinal epithelium.10–12 These evolutionarily ancient innate immunity receptors function independently of the more recently evolved adaptive immune mechanisms. Proteins derived from microorganisms and viruses act as ligands for the 10 known TLRs, stimulating rapid protective cellular responses. 13 Ongoing studies in several laboratories have revealed the presence of these receptors in airway epithelial cell lines, as well as modulation of epithelial cell gene expression on TLR activation.14–16 Currently, the role of TLRs in CRS remains entirely unexplored.

There are several known proteins present in normal nasal secretions that have antibacterial properties or facilitate host defense.17,18 Of these, many are produced locally, such as defensins, lactoferrin, lysozyme, and secretory immunoglobulin. In addition, components of the complement cascade and other acute phase proteins can be found in the nasal mucus, particularly during inflammation.1 Because these substances are produced principally in the liver, this phenomenon, traditionally, has been thought to reflect increased vascular exudation, rather than local production. Complement components in the mucus are available for activation through either the classic or the alternative pathways. An important occurrence in complement activation is the cleavage of complement component 3 (C3) into C3a and C3b. C3a, an anaphylatoxin, enhances the inflammatory state by causing increased small vessel permeability, vasodilation, and histamine release. C3a is a potent chemoattractant for granulocytes, including eosinophils, that also promotes the adherence of eosinophils to endothelium and stimulates release of granule contents such as eosinophil cationic protein.19–21 Moreover, the other C3 cleavage product, C3b, binds to microbial surfaces, which opsonizes the microorganisms for phagocytosis and activates C3b receptors on eosinophils and other phagocytic cell types. Because recruitment and activation of eosinophils are features of CRS, these properties of C3 products could be important in producing the characteristic histological features observed in chronic polypoid eosinophilic rhinosinusitis.

Poised at the interface between the host and the external environment, sinonasal epithelial cells are likely to play an important role in innate immune mechanisms and may provide a critical link between innate and adaptive limbs of mucosal immunity. In the context of CRS, epithelial cells are in constant contact with airborne antigens and may be capable, directly or indirectly, of modulating immune responses to them. Therefore, through pattern-recognition receptors and the production of inflammatory mediators, epithelial cells may be more active participants in the pathogenesis of CRS than previously recognized. Recent microarray studies of cultured human lower epithelial cells have shown that stimulation of TLRs leads to significant expression of C3 and the acute phase proteins serum amyloid A (SAA) and properdin.16 In this study, we investigate the hypothesis that TLRs, SAA, and properdin are expressed in sinonasal mucosa from CRS patients. Specifically, we use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to establish the presence of message for TLR1–10, C3, SAA, and properdin in surgically obtained sinonasal epithelial specimens from patients with CRS. Expression of C3 protein was confirmed by immunohistochemistry. These findings provide preliminary and supportive evidence that sinonasal epithelial cells may respond to extramucosal stimulation of innate immune receptors with local production of complement and acute phase proteins, providing an immediate line of defense before initiation of the adaptive immune response.

METHODS

Sinonasal Mucosal Specimens

Human sinonasal mucosa was obtained from 20 subjects undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery for CRS and 5 control subjects undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery for orbital decompression, cerebrospinal fluid leak repair, or resection of a sphenoid sinus lesion. The study protocol was approved through the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review process, and all subjects gave signed informed consent. Patients were defined as having CRS by radiographic criteria and by meeting the definition of the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery CRS Task Force.22 Specifically, the patients had continuous symptoms of rhinosinusitis as defined by the Task Force report for >12 consecutive weeks, associated with computed tomography of the sinuses revealing isolated or diffuse sinus mucosal thickening or air-fluid levels. Surgery was performed only if a patient’s symptoms and radiographic findings failed to resolve despite at least 4 weeks of treatment with oral antibiotics, oral and topical corticosteroids, decongestants, and mucolytic agents. The tissue specimens were taken from the resected uncinate process and anterior ethmoid sinus. The specimens were selected carefully to avoid polyps or tissue that was grossly polypoid in appearance. The specimens were immediately divided into two separate portions, one placed in RNAlater (Ambion, Austin, TX) and the other in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.05 M of phosphate buffer and 0.9% sodium chloride, pH 7.4). The samples were refrigerated until processing was performed.

Immunohistochemistry

Paraformaldehyde-fixed samples were rinsed in PBS and cryoprotected with 18% sucrose in PBS (18–24 hours at 4°C). Alternate cryostat sections (10 µm) were collected on lysine-coated slides, dried briefly, and incubated at room temperature with blocking solution containing 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and 10% normal goat serum for 60 minutes. Each slide was covered with a solution containing monoclonal mouse antiserum (20 hours at 4°C) against human C3 complement (clone HAV 3–4; Dako A/S, Glostrup, Denmark). The primary antibody was diluted in PBS containing 1% BSA and 0.1% Triton X-100 (PBS BSA-T). Negative control slides were incubated in a similar fashion covered with buffer containing mouse immunoglobulin G1 or rabbit serum. Slides were washed with PBS BSA-T and then incubated (2 hours at room temperature) with goat anti-mouse biotinylated secondary antibody. Slides were then washed twice with PBS, incubated with Vectastain avidin-biotin peroxidase complex (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), washed, and then incubated with the Vector diaminobenzidine-hydrogen peroxide chromogen kit. The slides are then washed twice with distilled water, counterstained in Mayer’s hematoxylin for 30 seconds, washed, dehydrated through graded alcohols and xylene substitutes twice, and then permanently mounted. Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO).

Slides were counted in coded random order by two blinded independent observers using a microscope equipped for bright-field microscopy with an eyepiece graticule (0.202 mm2) or on a digitized captured image. For immunohistochemistry, positive cells or tissue (stained brown by the diaminobenzidine chromogen) are compared with background staining in a neighboring section of tissue.

RNA Extraction/Reverse Transcription

Total messenger RNA (mRNA) was isolated from the stored mucosa using the TRIzol (0.8 mL) reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and DNA was removed using DNAfree (Ambion,) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Isolated mRNA was reverse transcribed using a poly(dT)15 primer (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) and Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) using conditions provided by the manufacturer. Samples were visualized using agarose gel electrophoresis.

Real-Time-PCR

Real-time PCR (RT-PCR) was performed in an ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detection System thermal cycler (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) to quantify target and β-actin mRNA. Primers and probes were designed using Primer Express 1.5 software (PE Applied Biosystems) from sequences stored in the GenBank sequence database. Target genes, primers, and probes used are listed in Table 1. The β-actin served as a housekeeping gene for standardization. Utility of each primer-probe combination in the assessment of complement pathway genes was confirmed by testing with internal positive control samples using human liver mRNA. Gel electrophoresis was used to confirm the formation of a single amplification product.

Table 1.

Primer/Probe Combinations for TLRs, C3, properdin, SAA, and β-Actin

| Target | Forward Primer | Reverse Primer | Probe |

|---|---|---|---|

| TLR1 | TCAAGACTGTAGCAAATCTGGAACTATC | TTTCAAAAACCGTGTCTGTTAAGAGA | TGCCCATCCAAAATTAGCCCGTTCCTA |

| TLR2 | GGCCAGCAAATTACCTGTGTG | AGGCGGACATCCTGAACCT | CCATCCCATGTGCGTGG |

| TLR3 | CCTGGTTTGTTAATTGGATTAACGA | GATTGGTCTTCCTTTTCCATTGAA | CATACCAACATCCCTGAGCT |

| TLR4 | GCAGTGAGGATGATGCCAGGAT | GCCATGGCTGGGATCAGAGT | TGTCTGCCTCGCGCC |

| TLR5 | TGCCTTGAAGCCTTCAGTTATG | CCAACCACCACCATGATGAG | CCAGGGCAGGTGCTTATCTGACCTTAACA |

| TLR6 | GAAGAAGAACAACCCTTTAGGATAGC | AGGCAAACAAAATGGAAGCTT | TGCAACATCATGACCAAAGACAAAGAACCTA |

| TLR7 | TTACCTGGATGGAAACCAGCTAC | TCAAGGCTGAGAAGCTGTAAGCTAG | AGATACCGCAGGGCCTCCCGC |

| TLR8 | AGCGGATCTGTAAGAGCTCCATC | CCGTGAATCATTTTCAGTCAAGAC | CCTGACAACCCGAAGGCAGAAGGC |

| TLR9 | GCAGTCAATGGCTCCCAGTTC | GCGGTAGCTCCGTGAATGAGTG | CCCGCAATAAGCTG |

| TLR10 | TTATGACAGCAGAGGGTGATGC | CTGGAGTTGAAAAAGGAGGTTATAGG | TTGACCCCAGCCACAACGACACTG |

| PF | ACCCACATCTGCAACACAGCT | CCCGCGTGACTGGTGG | CTGTCAAGAAATCC |

| SAA | CTTGGCGAGCCTTTTGATG | TAGTTCCCCCGAGCATGG | ACATGAGAGAAGCCAATTA |

| C3 | AGAAAGACATGGCCCTCACG | TCGCAAATATCTTTAGCCTCCTG | CTTTGTTCTCATCTCGC |

| β-Actin | CTGGCCGGGACCTGAT | GCAGCCGTGGCCATCTC | CACCACCACGGCCA |

One microliter of each complementary DNA (cDNA) preparation, corresponding to 25 µg of mRNA, was diluted 1:10 and 5 µL of this preparation was placed in a total volume of 25 µL with the following components: 1 × TaqMan PCR buffer, 5.5 mM of MgCl2, 0.25 mM of dNTPs (dATP, dCTP, dUTP, dGTP), 0.25 U of AmpErase uracil-N-glycosylase, 0.75 U of Ampli Taq Gold™ (Applied Biosystems), 0.4 µM of each primer, and 0.2 µM of the Taqman probe. Cycle parameters used were 50°C for 2 minutes to activate uracil-N-glycosylase and 95°C for 10 minutes to activate Taq, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds and 60°C for 1 minute. The fold change of target mRNA was expressed as (ΔCT = the difference in threshold cycles for target and β-actin).

RESULTS

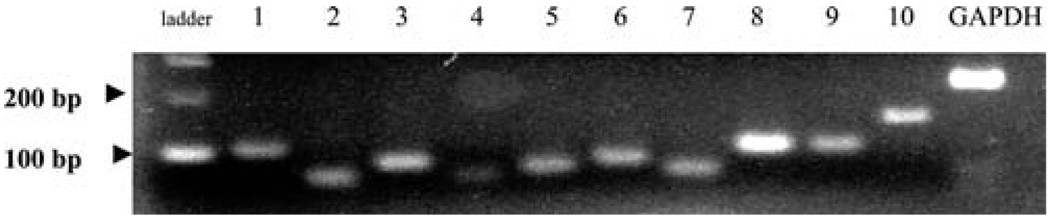

In previous studies, recently, we have screened bronchial epithelial cells for expression of mRNA for TLRs and found detectable levels of all known receptors.23 We hypothesized that human nasal tissue would contain mRNA for TLRs as well and, therefore, screened sinonasal tissue from 13 subjects. Figure 1 shows PCR products in a single subject. All products were found to migrate at the expected molecular weight based on standards. As seen in Fig. 1, variable expression of TLR was apparent by PCR. PCR results were scored according to whether there was no visible band (−), a visible but weak band (±), or a clearly visible band (+) for PCR assays from 13 different subjects (Table 2). Although there was some intersubject variability, these results indicate that all 10 TLRs were detected in human sinonasal mucosa.

Figure 1.

Representative expression of TLRs 1–10 in a sinonasal mucosa from a single subject.

Table 2.

Expression of TLRs in 13 CRS Sinonasal Mucosal Specimens

| Subjects | TLR1 | TLR2 | TLR3 | TLR4 | TLR5 | TLR6 | TLR7 | TLR8 | TLR9 | TLR10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | + | ± | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 2 | − | + | + | ± | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 3 | + | + | + | ± | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 4 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| 5 | + | + | + | − | − | ± | + | + | + | + |

| 6 | − | + | ± | ± | − | − | + | + | + | + |

| 7 | − | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 8 | − | + | + | − | + | ± | + | + | + | − |

| 9 | + | + | + | − | + | ± | + | + | + | − |

| 10 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| 11 | + | + | + | ± | + | − | + | + | + | + |

| 12 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | ± | ± |

| 13 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | + |

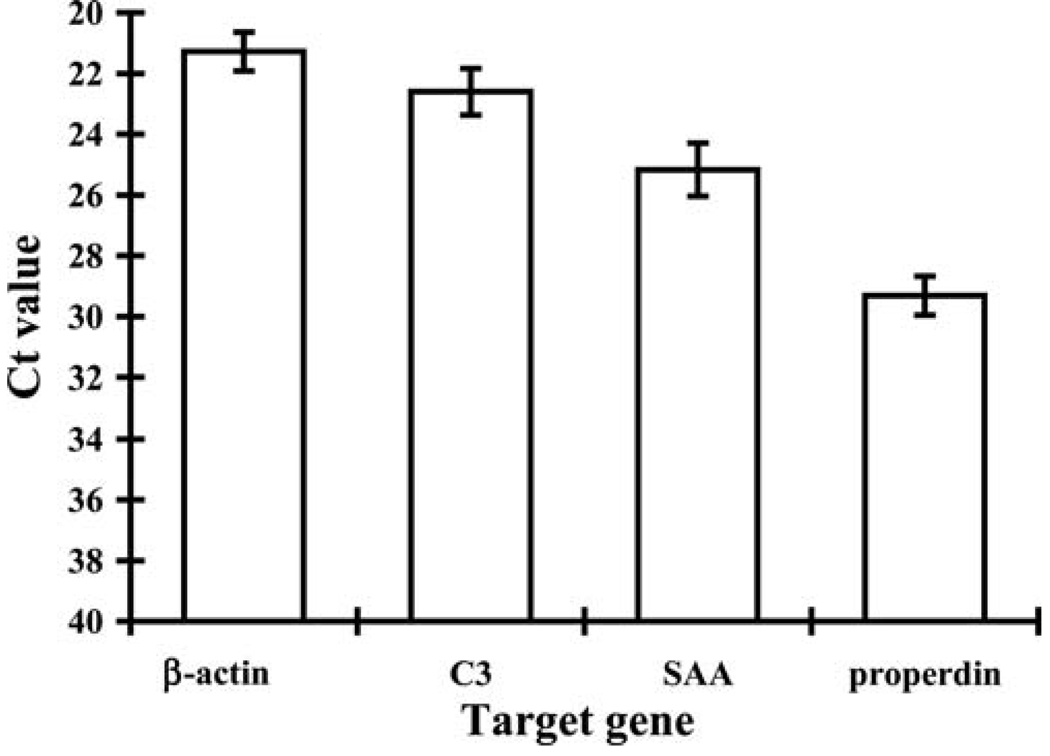

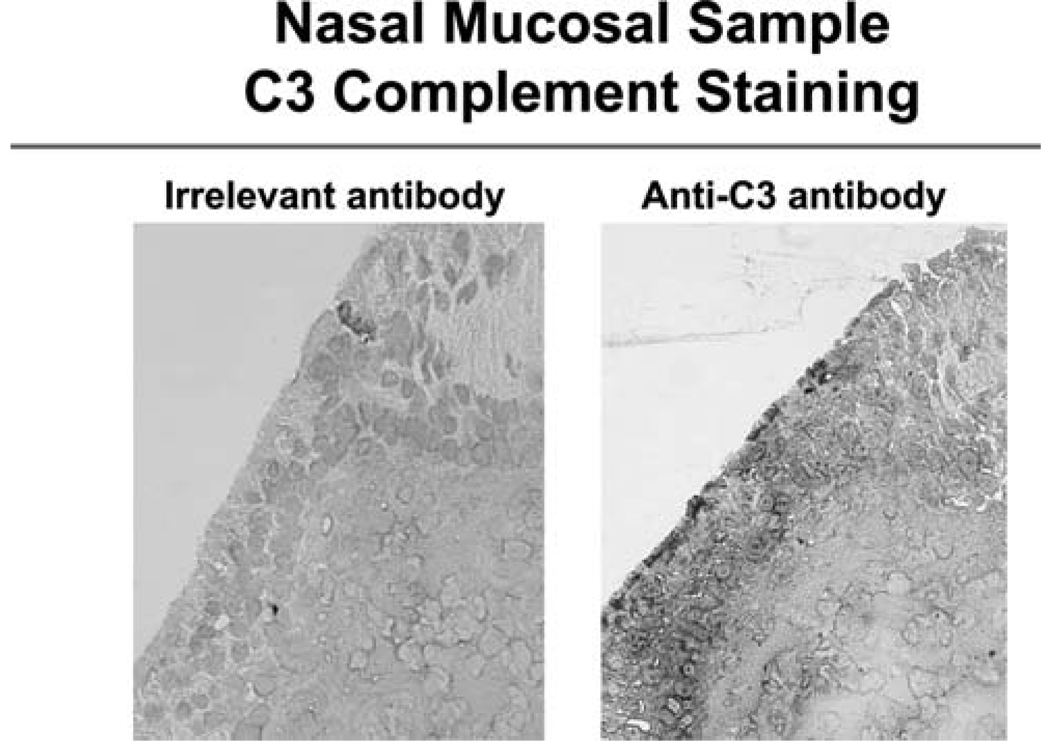

When airway epithelial cells were activated with TLR ligands in previous studies, especially double-stranded RNA (TLR3), lipopolysaccharide (TLR4), and flagellin (TLR5), we observed increased expression of the acute phase protein SAA and the complement proteins C3 and properdin. Therefore, we screened sinonasal cDNA samples for mRNA encoding these three proteins using RT-PCR. Analysis of the sinonasal sample mRNA revealed expression of all three genes assayed. Based solely on threshold (CT) values, the amount of mRNA for C3 was greatest, followed by SAA, and then properdin. To confirm expression of C3, we performed immunohistochemistry using a specific monoclonal antibody (Fig. 2). Immunohistochemical analysis of 13 nasal samples showed C3 staining localized to the apical portion of the sinonasal epithelium in 9 nasal samples. The regions of staining ranged from 20 to 85% of the total epithelium present on the tissue section. Analysis of the five control specimens also showed similar expression of TLRs, C3, properdin, and SAA.

Figure 2.

RT-PCR showing the relative expression of β-actin, C3, SAA, and properdin in eight sinonasal mucosal specimens. Data shown are means with SEM.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study establish that sinonasal tissue expresses the pattern-recognition receptors TLR1–10, which recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns. These genes are expressed both in control subjects and in CRS patients. We observed intersubject variability in the presence of mRNA for TLR (see Table 2). Some TLRs were consistently detected in all subjects evaluated (TLR2, TLR3, TLR7, and TLR8). Interestingly, TLR4 was expressed in the fewest subjects tested. Low expression of TLR4 has been reported in gastrointestinal epithelium.24 A study by Claeys et al. indicated similar levels of TLR4 expression in nasal mucosa and adenotonsillar tissue, while levels of TLR2 were significantly reduced in the nasal mucosa.12 Stimulation of TLRs in airway epithelial cell lines results in the expression of SAA, properdin, and C3.16 We have shown here that mRNA for these same complement and acute phase proteins is present in normal and diseased sinonasal mucosa. Taken together, these findings suggest that extrahepatic production of these innate immune mediators occurs within the mucosal surface, perhaps in response to stimulation of TLRs. Given that sinonasal epithelial cells are in contact with inhaled particulates, microorganisms, and viruses, the production of acute phase proteins at the mucosal interface may represent a first-line mechanism of innate defense against specific pathogens recognized by TLRs. This would represent a novel immune pathway with a possible role in the pathogenesis of chronic sinonasal inflammatory disease. Depending on the precise role that innate epithelial cellular responses to pathogens play, overactivity or underactivity of these defensive systems might be exacerbating factors in CRS.

The finding that the acute phase proteins are produced in sinonasal tissue is not wholly surprising. Although for many years the study of the expression and regulation of acute phase proteins has been performed almost exclusively in liver cells, it has been established in the literature that complement components and SAA also arise from extrahepatic sources in both health and disease.25–27 The recent discovery that acute phase proteins are present in atherosclerotic plaque and may contribute to coronary artery disease has spurred increased attention on extrahepatic production.28 Epithelial, monocyte-macrophage, and smooth muscle cell lines have all been shown to express SAA.29,30 Additionally, there is histological evidence that normal human epithelium, endothelium, and lymphocytes also express SAA in vivo.26 SAA may lead to the expression of proinflammatory genes through activation of the transcription factor nuclear factor κB and the protein kinases ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase.31,32 In addition, SAA has been shown to bind to the outer membrane proteins of Gram-negative bacteria such as pseudomonas. 33 Extrahepatic production of acute phase proteins allows for tissue-specific expression that may have important local effects in the absence of a systemic inflammatory state. In C3-deficient knockout mice rescued by bone marrow transfer, locally generated C3 was found to be more critical than serum C3 in the amplification of humoral immunity.34 In the nose and paranasal sinuses, locally produced complement and acute phase proteins may similarly play a more critical role than serum proteins released through vascular exudation. Thus, in the setting of CRS, it is possible that complement proteins and SAA produced locally by epithelial cells, perhaps in response to external stimuli, influence local immune responses and the mucosal inflammatory state.

Similar to asthma and inflammatory bowel disease, CRS is a disorder of mucosal immunity where mucosal function becomes impaired by infiltration with leukocytes and elaborated inflammatory mediators. Although the inflammation in CRS is Th2-skewed and dominated by eosinophils, mononuclear and even neutrophilic infiltrates are not uncommon. One of the hallmarks of CRS is the clustering of activated and degranulating eosinophils within the mucus layer, often surrounding particulate matter such as fungal elements.35,36 It is well recognized that airway irritants, allergens, microorganisms, and viruses can exacerbate the airway mucosal inflammatory state in susceptible individuals. 36–40 The mechanisms by which extramucosal agents trigger the immune system to produce the leukocyte infiltration associated with CRS is unclear. Although it generally is accepted that lymphocyte populations can drive these responses, it is becoming increasingly clear that epithelial cells, situated at the boundary of the mucosa, have a role in the early detection and immediate response to external stimuli. The hypothesis that innate responses of the sinonasal epithelium to environmental antigens may promote or perpetuate the eosinophilic inflammation of chronic polypoid eosinophilic rhinosinusitis has not been proposed or investigated previously.

Our preliminary findings might suggest a model in which epithelial cells interact with pathogen-associated molecules at the mucosal surface, including bacterial, fungal, and viral elements, using TLRs expressed on their apical surfaces (Fig. 3). In response to stimulation of the TLRs, there is production of host defense proteins, as well as cytokines necessary to initiate a local response to the pathogen. The specific types of cytokines and mediators produced may be determined by which type of TLR is stimulated. Epithelial cells also may internalize and process samples of antigen from their apical surfaces for direct presentation to intraepithelial lymphocytes in the context of major histocompatability complex (MHC) and costimulatory molecules. In these ways, epithelial cells may act as a critical bridge between innate and adaptive immunity at the mucosal surface of the nose and sinuses. In the setting of CRS, where there is underlying Th2-type inflammation present in the epithelium, innate immune responses of the epithelium may critically influence eosinophil activation. The local generation of the complement protein C3 on stimulation of epithelial cell TLRs could potentiate the recruitment of eosinophils and other leukocytes that express receptors for C3a to the mucosal surface, where opsonized particulate matter would stimulate degranulation. Alternatively, the absence or decreased function of these same protective innate epithelial cell responses may be a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of other forms of CRS by allowing excessive colonization of the upper airways.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining showing C3 expression in the apical portion of the sinonasal epithelium (20× magnification).

It should be pointed out that a limitation of using PCR to assess gene expression in sinonasal tissue specimens is that the cellular source of the measured mRNA can not be determined. Sinonasal biopsy specimens contain a wide variety of cell types within the epithelium and subepithelium, as well as in the underlying periosteum and bone. This becomes a particular problem when studying the effect of inflammatory disease on gene expression by PCR, because observed differences between CRS and control may largely reflect the contribution of infiltrating inflammatory cells, rather than normal resident cell populations. For example, an increase in apparent TLR4 expression in CRS tissue as compared with control may be entirely caused by the presence of TLR4 mRNA in invading leukocytes that are not present in control tissue, while the level of TLR4 expression by epithelial cells may be unchanged or even decreased. Future studies examining the effect of CRS on innate immune mediator expression will require localizing techniques such as in situ hybridization or immunohistochemistry to identify cellular sources and clarify such potentially misleading findings. Another limitation imposed by the use of mucosal biopsy specimens is that functional analysis of the proteins in question can not be achieved unless the tissue is maintained in organ culture and manipulated experimentally. Therefore, even though it may be inferred from our in vitro studies of airway epithelial cells in culture, the relationship between TLR activation and innate immune mediator production is not established in the present study. Similarly, recent articles that have speculated a role for TLR2 and TLR4 as upper airway sensors of bacterial infection also do not offer direct functional evidence.12 The link between the presence of TLR mRNA and expression of innate immune mediators such as defensins in the human upper airway still has to be established in vivo, although it does make an attractive hypothesis for how upper airway bacterial pathogens activate local immune pathways.41

Eosinophilic polypoid CRS is a frustrating disorder for patients and physicians alike because it often is resistant to medical and surgical therapy. Although much recent attention has been focused on the identification of microorganisms or antigens that may act as triggers of the persistent inflammatory state, research into the mechanisms of pathogen recognition and the subsequent innate sinonasal mucosal responses may offer new insights into the underlying disease process. Current investigations underway in our laboratories seek to explore the role of these immune pathways in normal nasal physiology as well as in disease. Ultimately, a greater understanding of sinonasal innate immune function may lead to novel pharmacologic approaches to the treatment of CRS and better management of this increasingly prevalent and poorly controlled condition.

Acknowledgments

Research funded in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants HL68546 and AI50530

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaliner MA. Human nasal respiratory secretions and host defense. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1991;144:S52–S56. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/144.3_pt_2.S52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee SH, Kim JE, Lim HH, et al. Antimicrobial defensin peptides of the human nasal mucosa. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2002;111:135–141. doi: 10.1177/000348940211100205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fakhri S, Frenkiel S, Hamid QA. Current views on the molecular biology of chronic sinusitis. J Otolaryngol. 2002;31 suppl 1:S2–S9. doi: 10.2310/7070.2002.21307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachert C, Gevaert P, Holtappels G, van Cauwenberge P. Mediators in nasal polyposis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2002;2:481–487. doi: 10.1007/s11882-002-0088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hamilos DL. Chronic sinusitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:213–227. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.109269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamilos DL, Leung DY, Wood R, et al. Eosinophil infiltration in nonallergic chronic hyperplastic sinusitis with nasal polyposis (CHS/NP) is associated with endothelial VCAM-1 upregulation and expression of TNF-alpha. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1996;15:443–450. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.4.8879177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mills PR, Davies RJ, Devalia JL. Airway epithelial cells, cytokines, and pollutants. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1999;160:S38–S43. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.supplement_1.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mio T, Romberger DJ, Thompson AB, et al. Cigarette smoke induces interleukin-8 release from human bronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155:1770–1776. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.5.9154890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rusznak C, Devalia JL, Sapsford RJ, Davies RJ. Ozone-induced mediator release from human bronchial epithelial cells in vitro and the influence of nedocromil sodium. Eur Respir J. 1996;9:2298–2305. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09112298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Imler JL, Hoffmann JA. Toll receptors in innate immunity. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:304–311. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gewirtz AT. Intestinal epithelial toll-like receptors: To protect. And serve? Curr Pharm Des. 2003;9:1–5. doi: 10.2174/1381612033392422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Claeys S, de Belder T, Holtappels G, et al. Human beta-defensins and toll-like receptors in the upper airway. Allergy. 2003;58:748–753. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.2003.00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barton GM, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and their ligands. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2002;270:81–92. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59430-4_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shuto T, Imasato A, Jono H, et al. Glucocorticoids synergistically enhance nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae-induced Toll-like receptor 2 expression via a negative cross-talk with p38 MAP kinase. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:17263–17270. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112190200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond G, Legarda D, Ryan LK. The innate immune response of the respiratory epithelium. Immunol Rev. 2000;173:27–38. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.917304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sha Q, Truong-Tran AQ, Plitt JR, et al. Activation of airway epithelial cells by toll-like receptor agonists. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2004;31:358–364. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0388OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raphael GD, Jeney EV, Baraniuk JN, et al. Pathophysiology of rhinitis. Lactoferrin and lysozyme in nasal secretions. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:1528–1535. doi: 10.1172/JCI114329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frye M, Bargon J, Dauletbaev N, et al. Expression of human alpha-defensin 5 (HD5) mRNA in nasal and bronchial epithelial cells. J Clin Pathol. 2000;53:770–773. doi: 10.1136/jcp.53.10.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Daffern PJ, Pfeifer PH, Ember JA, Hugli TE. C3a is a chemotaxin for human eosinophils but not for neutrophils. I. C3a stimulation of neutrophils is secondary to eosinophil activation. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2119–2127. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.DiScipio RG, Daffern PJ, Jagels MA, et al. A comparison of C3a and C5a-mediated stable adhesion of rolling eosinophils in postcapillary venules and transendothelial migration in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 1999;162:1127–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takafuji S, Tadokoro K, Ito K, Dahinden CA. Degranulation from human eosinophils stimulated with C3a and C5a. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1994;104 suppl 1:27–29. doi: 10.1159/000236743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benninger MS, Ferguson BJ, Hadley JA, et al. Adult chronic rhinosinusitis: definitions, diagnosis, epidemiology, and pathophysiology. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129 suppl 3:S1–S32. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(03)01397-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sha QPJ, Heller NM, Beck LA, et al. Airway epithelial cell activation and toll-like receptors (TLRs) J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:S212. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abreu MT, Vora P, Faure E, et al. Decreased expression of Toll-like receptor-4 and MD-2 correlates with intestinal epithelial cell protection against dysregulated proinflammatory gene expression in response to bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2001;167:1609–1616. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khirwadkar K, Zilow G, Oppermann M, et al. Interleukin-4 augments production of the third complement component by the alveolar epithelial cell line A549. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1993;100:35–41. doi: 10.1159/000236384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Urieli-Shoval S, Cohen P, Eisenberg S, Matzner Y. Wide-spread expression of serum amyloid A in histologically normal human tissues. Predominant localization to the epithelium. J Histochem Cytochem. 1998;46:1377–1384. doi: 10.1177/002215549804601206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walters DM, Breysse PN, Schofield B, Wills-Karp M. Complement factor 3 mediates particulate matter-induced airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27:413–418. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.4844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamada T, Kakihara T, Kamishima T, et al. Both acute phase and constitutive serum amyloid A are present in atherosclerotic lesions. Pathol Int. 1996;46:797–800. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1996.tb03552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steel DM, Donoghue FC, O’Neill RM, et al. Expression and regulation of constitutive and acute phase serum amyloid A mRNAs in hepatic and non-hepatic cell lines. Scand J Immunol. 1996;44:493–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1996.d01-341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Urieli-Shoval S, Linke RP, Matzner Y. Expression and function of serum amyloid A, a major acute-phase protein, in normal and disease states. Curr Opin Hematol. 2000;7:64–69. doi: 10.1097/00062752-200001000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jijon HB, Madsen KL, Walker JW, et al. Serum amyloid A activates NF-kappaB and proinflammatory gene expression in human and murine intestinal epithelial cells. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:718–726. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baranova IN, Vishnyakova TG, Bocharov AV, et al. Serum amyloid A binding to CLA-1 (CD36 and LIMPII analogous-1) mediates serum amyloid A protein-induced activation of ERK1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:8031–8040. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405009200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hari-Dass R, Shah C, Meyer DJ, Raynes JG. Serum amyloid a protein binds to outer membrane protein A of gram-negative bacteria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(19):18562–18567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500490200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fischer MB, Ma M, Hsu NC, Carroll MC. Local synthesis of C3 within the splenic lymphoid compartment can reconstitute the impaired immune response in C3-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1998;160:2619–2625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taylor MJ, Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, et al. Detection of fungal organisms in eosinophilic mucin using a fluorescein-labeled chitin-specific binding protein. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:377–383. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.128896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ponikau JU, Sherris DA, Kern EB, et al. The diagnosis and incidence of allergic fungal sinusitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:877–884. doi: 10.4065/74.9.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinto JM, Baroody FM. Chronic sinusitis and allergic rhinitis: At the nexus of sinonasal inflammatory disease. J Otolaryngol. 2002;31 suppl 1:S10–S17. doi: 10.2310/7070.2002.21310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Osur SL. Viral respiratory infections in association with asthma and sinusitis: A review. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;89:553–560. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)62101-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dockery DW, Pope CA., III Acute respiratory effects of particulate air pollution. Annu Rev Public Health. 1994;15:107–132. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pu.15.050194.000543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cazzola M, Matera MG, Rossi F. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness and bacterial respiratory infections. Clin Ther. 1991;13:157–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Seitz M. Toll-like receptors: Sensors of the innate immune system. Allergy. 2003;58:1247–1249. doi: 10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]