Abstract

Accurate mortality statistics, needed for population health assessment, health policy and research, are best derived from data in vital registration systems. However, mortality statistics from vital registration systems are not available for several countries including Viet Nam. We used a mixed methods case study approach to assess vital registration operations in 2006 in three provinces in Viet Nam (Hòa Bình, Thùa Thiên–Hué and Bình Duong), and provide recommendations to strengthen vital registration systems in the country. For each province we developed life tables from population and mortality data compiled by sex and age group. Demographic methods were used to estimate completeness of death registration as an indicator of vital registration performance. Qualitative methods (document review, key informant interviews and focus group discussions) were used to assess administrative, technical and societal aspects of vital registration systems. Completeness of death registration was low in all three provinces. Problems were identified with the legal framework for registration of early neonatal deaths and deaths of temporary residents or migrants. The system does not conform to international standards for reporting cause of death or for recording detailed statistics by age, sex and cause of death. Capacity-building along with an intersectoral coordination committee involving the Ministries of Justice and Health and the General Statistics Office would improve the vital registration system, especially with regard to procedures for death registration. There appears to be strong political support for sentinel surveillance systems to generate reliable mortality statistics in Viet Nam.

Résumé

Pour disposer de statistiques de mortalité exactes, nécessaires pour évaluer la santé d’une population, définir une politique sanitaire ou mener des recherches en santé, le mieux est d’obtenir ces statistiques à partir des systèmes d’enregistrement des données d’état-civil. Cependant, dans plusieurs pays dont le Viet Nam, on ne dispose pas de statistiques de mortalité établies à partir des systèmes d’enregistrement des données d’état-civil. Nous avons adopté une démarche du type étude de cas par des méthodes mixtes pour évaluer le fonctionnement en 2006 des registres d’état-civil de trois provinces du Viet Nam (Hòa Bình, Thùa Thiên Hué et Binh Duong) et formuler des recommandations visant au renforcement des systèmes d’enregistrement des données d’état-civil dans ce pays. Pour chaque province, nous avons établi des courbes de survie à partir des données concernant la population et des chiffres de mortalité, compilés par sexe et par tranche d’âge. Nous avons employé des méthodes démographiques pour estimer la complétude des registres des décès en tant qu’indicateur de performance pour l’enregistrement des données d’état-civil. Nous avons fait appel à des méthodes qualitatives (revue des documents, entretiens avec des informateurs clés et discussions par groupes thématiques) pour évaluer les aspects administratifs, techniques et sociétaux de ces systèmes d’enregistrement. Dans les trois provinces, le niveau de complétude de l’enregistrement des décès était faible. Nous avons identifié des problèmes concernant le cadre juridique de l’enregistrement des décès néonatals précoces et des décès touchant les résidents temporaires et les migrants. Le système d’enregistrement n’est pas conforme aux normes internationales pour la notification des causes de décès ou pour l’enregistrement des statistiques détaillées par âge, sexe et cause de décès. Un renforcement des capacités, en parallèle avec la mise en place d’un comité de coordination intersectoriel impliquant les ministères de la justice et de la santé et le Bureau général des statistiques, devrait conduire à une amélioration du système d’enregistrement des données d’état-civil et notamment des procédures d’enregistrement des décès. Il nous semble qu’il existe un fort soutien politique aux systèmes de surveillance sentinelle dans la production de statistiques de mortalité fiables au Viet Nam.

Resumen

Los sistemas de registro civil son la mejor fuente para elaborar las estadísticas de mortalidad precisas que se requieren para evaluar la salud de la población y dar forma a las políticas e investigaciones sanitarias. Sin embargo, son varios los países sobre los que no se dispone de estadísticas de mortalidad basadas en esos sistemas, entre ellos Viet Nam. Utilizamos una modalidad de estudio de casos basado en varios métodos para evaluar la información introducida en los sistemas de registro civiles en 2006 en tres provincias de Viet Nam (Hòa Bình, Thùa Thiên–Hué y Bình Duong) y formular recomendaciones para fortalecer esos sistemas en el país. Para cada provincia elaboramos tablas de mortalidad a partir de los datos de población y mortalidad recopilados por grupos de sexo y edad. Se emplearon métodos demográficos para estimar la completud de los registros de defunciones como indicador de la validez del registro civil. Se emplearon también métodos cualitativos (examen de documentos, entrevistas a informantes clave y grupos de discusión focalizados) para evaluar los aspectos administrativos, técnicos y sociales de los sistemas de registro civil. El grado de completud de los registros de defunciones fue bajo en las tres provincias. Se detectaron problemas relacionados con las disposiciones legales para el registro de las defunciones neonatales tempranas y las defunciones de residentes temporales o migrantes. El sistema no se ajusta a las normas internacionales de notificación de las causas de defunción o el registro de estadísticas detalladas por edad, sexo y causa de defunción. La creación de capacidad, así como de un comité de coordinación intersectorial que implique a los Ministerios de Justicia y Salud y la Oficina General de Estadísticas, mejoraría el sistema de registro civil, especialmente en lo que atañe a los procedimientos de registro de las defunciones. Parece que se está prestando un sólido apoyo político a los sistemas de vigilancia centinela para obtener estadísticas fiables de mortalidad en Viet Nam.

ملخص

أفضل وسيلة لجمع الاحصائيات الدقيقة للوفيات، التي يُحتاج إليها لتقييم صحة السكان وللسياسات الصحية والبحوث، هي جمعها من نظام السجل المدني. إلا أن إحصائيات الوفيات في نظام السجل المدني غير موجودة في العديد من البلدان ومنها فيتنام. استخدم الباحثون نهجاً من الطرق المشتركة لدراسة الحالة من أجل تقييم عمليات التسجيل الحيوي في عام 2006 في ثلاث مناطق في فيتنام (هوا-بنه، ثواثين-هو، بنه-دونغ)، وقدم الباحثون توصيات لتعزيز نظم التسجيل الحيوي في فيتنام. وأعدّ الباحثون لكل منطقة جداول الوفيات من واقع بيانات السكان والوفيات المجموعة حسب الجنس والفئات العمرية. واستُخدِمت طرق ديموغرافية لتقدير اكتمال تسجيل الوفاة كمؤشر لأداء التسجيل الحيوي. واستُخدِمت طرق لتقييم الجودة (مثل مراجعة الوثائق، والمقابلات مع المبلّغين الرئيسيين، والمجموعات المحورية للنقاش) وذلك لتقييم الجوانب الإدارية، والتقنية، والاجتماعية لنظم التسجيل الحيوي. وتبيّن أن إكمال تسجيل الوفاة كان منخفضاً في جميع المناطق الثلاثة. وجرى تحديد مشاكل في الإطار القانوني لتسجيل الوفيات المبكرة للمواليد الجدد ووفيات المهاجرين والمقيمين المؤقتين. والنظام لم يراع المعايير الدولية للتبليغ عن سبب الوفاة، أو تسجيل الإحصائيات بالتفصيل حسب العمر، والجنس، وسبب الوفاة. وسيؤدي بناء القدرات بجانب وجود لجنة للتنسيق بين القطاعات تضم وزارات العدل والصحة ومكتب الإحصاء العام إلى تحسين نظام التسجيل الحيوي، ولاسيما بخصوص إجراءات تسجيل الوفاة. ويبدو أن هناك دعماً سياسياً قوياً لإعداد نظم ترصد مخفرية لإصدار إحصائيات وفيات يعتمد عليها في فيتنام.

Introduction

Reliable mortality statistics, the cornerstone of national health information systems, are necessary for population health assessment, health policy and health service planning, programme evaluation and epidemiological research. These data are essential for monitoring progress towards the health-related United Nations Millennium Development Goals of reducing child and maternal mortality, and mortality from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria.1 They are also required to assess the impact of noncommunicable diseases, emerging infectious diseases, injuries and natural disasters. The World Health Organization (WHO) compiles mortality statistics by age, sex and cause reported by Member States on an ongoing basis.2 However, mortality statistics have not been published for Viet Nam,3 which had an estimated population of 88 million in 2009.4

The Global Burden of Disease study used a combination of statistical models and local data to estimate mortality in 2001 for countries that had not yet published data.5 In Viet Nam, total mortality was estimated from model life tables with under-five mortality measures derived from birth history surveys as model inputs. Cause-of-death patterns in Viet Nam were assumed to approximate a combination of estimated patterns for Chinese, Indian and Thai populations.5 The resultant Vietnamese mortality and cause-of-death estimates were anchored only weakly in local data. Mortality patterns were also derived around the same period (1999–2001) for a demographic surveillance site covering about 50 000 people in northern Viet Nam,6,7 but these data were limited in their generalizability due to small sample size and narrow geographic coverage.

Civil registration and vital statistics systems (vital registration systems) are considered the optimal source of mortality statistics because data on deaths recorded under legal provisions are likely to be complete.8 In Viet Nam, although civil registration was mandated under the first Vietnamese national civil code in 1956,9 no vital statistics from civil registration sources have been published to date. Hence a critical assessment of the operational characteristics of vital registration systems in Viet Nam was needed to identify limitations in the system’s ability to produce accurate local mortality statistics.

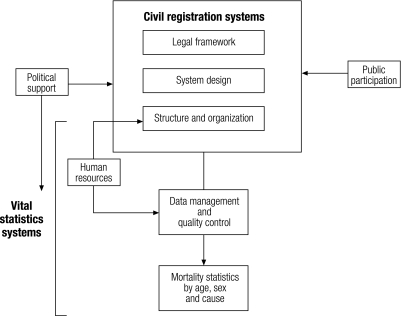

Vital registration systems operate through a complex network of agencies at different levels in the national administrative structure. These systems comprise two distinct but related operations: (i) registering vital events and issuing certificates of civil status, and (ii) compiling statistical information from vital records (Fig. 1). Assessments of vital registration systems should be based on a comprehensive framework10 that covers key aspects of their operations. The assessment framework we used explores administrative, technical and societal issues that influence civil registration systems.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual framework of elements that govern civil registration and vital statistics system operations in Viet Nam

First, administrative aspects were assessed through: (i) comprehensive review of the legal framework, including definitions of vital events and delegation of duties and responsibilities for reporting and registration; (ii) mapping of different elements in the structure and organization of registration and statistical processes; and (iii) scrutiny of the system design, in terms of the format and content of key documents used to record vital events, or to compile statistics.

Second, from a technical perspective, data management and quality assurance procedures together with the availability of skilled human resources were studied because of their critical influence on vital registration systems. Key technical aspects included compliance with international data standards, capacity to provide the cause of death, efficiency in the processing and management of vital records and statistical data, and periodic data evaluation with demographic and epidemiological methods.

Third, influences on vital registration systems have a societal perspective that involves the political will to support the system as well as public awareness and participation in the registration process. These critical aspects were considered because of the primordial role of government in implementing registration, encouraging civil participation in the reporting of vital events, and using vital statistics for health development.

Here we present the findings of a case study of civil registration and vital statistics systems in three provinces in Viet Nam. The assessment framework described above was used to critically examine the current availability and adequacy of the data that the system records. We also identified collaborative strategies that would allow key institutions in Viet Nam to develop interim and sustainable long-term solutions to improve data availability.

Methods

The study was conducted by researchers from the School of Population Health, University of Queensland (Brisbane, Australia) and Hanoi Medical University (Viet Nam). The Ministry of Justice of Viet Nam assisted in data collection and compilation. Fieldwork was conducted in three provinces selected to represent the three broad geographic areas of Viet Nam: (i) Hòa Bình, a province of the mountainous area in northern Viet Nam comprising the capital Hòa Bình and 10 rural districts divided into 214 communes; (ii) Thùa Thiên–Hué, a province in central Viet Nam comprising the capital Hué and eight rural districts divided into 150 communes; (iii) Bình Duong, a province in the Mekong Delta area in the south, comprising the capital Thu Dau Mot and six rural districts divided into 79 communes. This province hosts large industries that employ migrants from other provinces.

Qualitative methods

We reviewed all available publications on vital registration. Two communes in each province were visited to review registration documents and procedures. As key informants we interviewed the head of Civil Registration and Subdivision Administration from the Ministry of Justice in Hanoi and the provincial managers of the Register and Judicial Support Departments from each province studied. Focus group discussions involved Justice Department staff responsible for running the system at the district and commune levels. We focused on human interpretations and the social context of vital registration procedures. Interview and discussion transcripts were translated from Vietnamese to English, and translations were checked for quality and consistency by bilingual research team members and by an external reviewer. The qualitative data were coded to emergent themes related to the assessment framework and analysed for variations in practices at the province, district and commune levels.

Quantitative methods

We compiled detailed statistics on population and deaths by sex and 5-year age groups from population and vital event registers in each commune in the three study provinces for the year 2006. Annual population and cumulative death tallies were calculated for communes and analysed to produce abridged life tables by sex for each province for 2006.11 (Life tables are demographic models that summarize current age-specific mortality patterns in a population to calculate life expectancy at specific ages). Observed age-specific death rates from each province were assessed for completeness of adult death registration with the Brass growth balance indirect demographic method.12 This technique assesses completeness of death registration at ages older than 5 years by comparing the age distribution of reported deaths with the expected age distribution of deaths based on the observed population age structure, assuming the population is closed to migration.

Results

Administrative aspects

Legal framework

Our assessment showed that the current framework sets out duties and responsibilities at different echelons in the judicial hierarchy, and provides instructions on record-keeping, issuing certificates, submitting statistical data and supervisory roles (Table 1 available at: http://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/88/1/08-061630/en/index.html). One problem is the ambiguity in the requirements for registering deaths that occur within 24 hours of birth. The Civil Code states, “If a newborn child dies after birth, then both birth and death must be declared”.13 In contrast, guidelines issued by the Ministry of Justice say that deaths occurring within 24 hours of birth need not be registered.14 From another perspective, both the Code and the guidelines stipulate that fetal deaths need not be reported, which limits assessments of perinatal mortality.

Table 1. Evolution of legal framework for vital registration in Viet Nam.

| Characteristic of legal framework | Historical evolution and current status | |

|---|---|---|

| Duties and responsibilities for registration and vital statistics | • 1956–1998: death registration operated by Ministry of Domestic Affairs; 1998 onwards operated by Ministry of Justice. | |

| • 1956–1998: registration and issue of certificates free of charge. 1998 onwards, fees for registration and issuance of certificates. | ||

| • 2005 decree provides clear instructions on maintenance of vital records, issuance of certificates, processing corrections, submission of statistical returns; and registration services for Vietnamese citizens living abroad, in liaison with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. | ||

| Coverage | • Vietnamese decrees all mandate complete coverage. | |

| Reporting responsibilities and penalties | • 1956–1998: duty of relatives/persons of authority to notify death at place of occurrence; late registration punishable by law. | |

| • 1998–2005: notification document not required for death at place of usual residence. Late registration subject to financial penalties. | ||

| • 2005: death notice mandatory from health authority or responsible person for all deaths; no penalties for delayed registration. | ||

| Reporting period | • 1956–1961: death reported to local police within 24 hours to get burial permit, which is submitted within 7 days for death registration. | |

| • 1961–1998: death registration to be completed within 24 hours. | ||

| • 1998–2005: death registration to be completed within 48 hours in urban areas; within 15 days in remote and rural areas. | ||

| • 2005 onwards: death registration is required within 15 days of death. | ||

| Definitions for early age mortality | • No definitions of fetal death in terms of duration of gestation/birth weight in any version of Vietnamese decrees. | |

| • 1956 onwards: (according to civil code) fetal deaths require only burial permission, not registration. Neonatal deaths require both birth and death registration. | ||

| • 2005 onwards: (according to Ministry of Justice guidelines) deaths within 24 hours of birth do not require birth/death registration. | ||

| • 2005 onwards: infant deaths not reported by parents can be registered by the justice clerks. | ||

| Requirements for reporting cause of death | • 1956–1961: no mention of requirement to report cause of death. | |

| • 1961–1998: declarant should mention cause of death in death notice. | ||

| • 1998: “doubtful death”a requires cause of death issued by police. Death notice from health facilities must include cause of death. | ||

| • In 2005 decree, cause of death must be mentioned for all deaths. However, there is no stipulation regarding medical opinion as to the cause, nor specific format for reporting cause of death. | ||

| Compilation and submission of vital statistics | • 1998: compilation and submission of vital statistics first stipulated in the decree, including an annual report to Government. | |

| • 2005: submission of statistical reports from commune upwards every 6 months. Ministry of Justice responsible for summarizing the events and reporting to the Government annually. First annual national compilation of statistics achieved for 2007. |

a For example sudden death with no clear cause; death by accident; death by killing, suicide, doubtful murder, driven suicide; missing death; or others regulated by law.

A further problem was that the instructions regarding registration of deaths of temporary residents or migrants were unclear. In most instances a death notice must be submitted at the place of usual residence for death registration, although this is usually not done. Furthermore, there were no clear instructions on how to report, record or compile data on causes of death according to current international standards prescribed by the United Nations.8

System structure

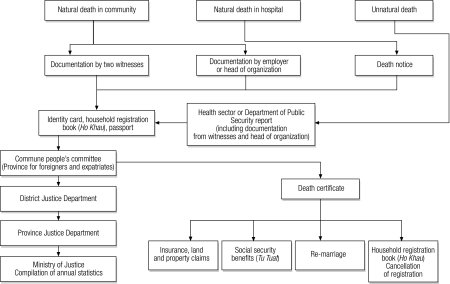

Fig. 2 depicts the structure of the current Vietnamese system – an example of “centralised administration with a single agency for civil registration and vital statistics”.15 This administrative structure has advantages for nationwide consistency in operation, and facilitates rapid, countrywide implementation of new policies. However, at the design stage the centralized structure should engage other governmental agencies or programmes that need registration and statistical information, i.e. the health sector, research organizations and other social services.15

Fig. 2.

Flow chart depicting the structure and organization of the civil registration and vital statistics system in Viet Nam, 2006

We found that national statistics agencies were not involved in data compilation or data management activities. Furthermore, although the health sector is required to furnish a death notice to the family in case of an institutional death, there is no direct reporting link between the health sector and the Ministry of Justice. Instead, the health sector operates a parallel system for recording births and deaths that relies on inputs from commune health staff, rather than any formal notification process by the public. These issues should be taken into account when planning reforms to vital registration systems in Viet Nam.

System design

The Ministry of Justice prescribes 16 specific forms and registers pertaining to civil status and residence, including births, deaths and marriages.16 For death registration, the required documents are: (i) an original document, i.e. a death notice from hospitals or documentation for community deaths from the employer or community witnesses (Fig. 2); (ii) the registration records, i.e. two copies of the death register maintained at the commune level, and the death certificate (a complete transcript of the death register) issued to relatives of the deceased; and (iii) the statistical report, i.e. a monthly return that compiles summary vital statistics including deaths in three age groups (0–1, 1–16 and > 16 years) and causes according to four categories (disease or old age, accidents, suicide and others).

The absence of detailed information on deaths by age, sex and cause in the monthly statistical summary report limit its usefulness for detailed demographic or epidemiological analyses.

Technical perspective

Compliance with standards

We found that the death notice from hospitals has only one line for reporting the cause of death, which does not comply with international recommendations to record immediate, antecedent, underlying and contributory causes.17 Also, there is no standard format for notifying deaths that occur in the community. The death register includes one column for recording the cause of death as mentioned in the original document.

Data inputs

Each commune maintains two copies of the death register; one copy is submitted annually to the district office. Communes also submit monthly statistical returns. Each district office cross-checks statistical returns against death registers and compiles annual summary vital statistics, which are submitted to the province and central offices. Mortality statistics for 2007 were compiled by the Ministry of Justice for each province in Viet Nam – the first national compilation of vital statistics ever (Dr Tran That, Ministry of Justice, Viet Nam, personal communication, July 2008). We found that the process for submitting statistical reports, verifying data and compiling summary vital statistics is functional, although the final data do not comply with prescribed data standards for population-wide mortality analyses with regard to age-specificity or detailed causes of death.18

Efficiency and human resources

In communes, vital registration and statistical data are compiled by justice clerks, who are certified in law or trained in vital registration by the Ministry of Justice. Clerks also make household visits to register deaths reported to them by other sources, e.g. population counsellors, health staff and police.

Focus group discussions with justice clerks revealed that training programmes are largely theoretical, with little supervision or on-site support to resolve practical issues. Irregularities result, particularly in the registration of infant and migrant deaths. Registration may be incomplete because details regarding identity or address are missing for deaths reported by other sources, or because time to make household visits is insufficient. Some justice clerks felt that their registration records were complete and up to date, based on their perceptions of proximity with the community and voluntary compliance with vital registration. This, however, was not borne out by reported statistics. In one commune with a population of over 10 000, only seven deaths were registered during a 2-year period, yielding an implausibly low annual death rate of 0.35 per 1000.

The current vital registration system lacks sufficient human resources to record detailed causes of death. To improve the efficiency and completeness of death registration, reforms should aim to increase human resources, i.e. health staff trained in conducting verbal autopsy interviews, physicians trained in cause-of-death certification, and statisticians trained in data coding, processing and tabulation.

Data evaluation

To evaluate data quality we used demographic analyses of detailed age- and sex-specific population and mortality data compiled from each commune (Table 2). The estimated low completeness of death registration at ages older than 5 years (32–51%) and low levels of under-five mortality compared with similar measures from survey-based data19 resulted in observed life expectancies at birth that were higher than modelled estimates.20 The observed crude death rates were also lower than rates from the 1999 census.21 Incomplete registration was also observed in a study that used direct matching methods in the demographic surveillance site in Bavi district.22 Taken together, these observations suggest that deaths are significantly under-registered.

Table 2. Summary measures of mortality for three provinces in Viet Nam, 2006, and comparisons with other sources.

| Indicator | Provinces |

Viet Nam: other sources |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hòa Bình |

Thùa Thiên–Hué |

Bình Duongo |

DHS 200219 |

WHO 200620 |

Census 199921 |

|||||||||||

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Persons | Male | Female | Male | Female | ||||||

| Life expectancy at birth (years) | 73 | 80.5 | 77 | 82.4 | 74 | 79 | NA | 69 | 75 | NA | NA | |||||

| Child mortalitya | 6.4 | 10.3 | 2.6 | 1.0 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 23.6 | 17 | 16 | NA | NA | |||||

| Adult mortalitya | 173 | 55 | 52 | 112 | 161 | 79 | NA | 194 | 116 | NA | NA | |||||

| Percent completeness of registration at ages > 5 | 40 | 31 | 37 | 42 | 32 | 35 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||

| Total population | 392 622 | 401 811 | 567 087 | 586 785 | 436 411 | 472 593 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||

| Number of deaths | 2057 | 1287 | 1748 | 1470 | 2103 | 1805 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | |||||

| Crude death ratesa | 5.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 2.5 | 4.8 | 3.8 | NA | NA | NA | 6.0 | 4.2 | |||||

DHS, Demographic and Health Surveys; NA, not available. WHO, World Health Organization. a Per 1000 population.

Societal perspective

Political will and support

Because governments are responsible for vital registration systems, they must provide adequate political will and support. While recognizing that we had no empirical basis for assessing political support for vital registration activities, we nonetheless identified several issues that reflect the current environment in Viet Nam. First, the most recent version of the relevant Ministry of Justice decree of 2005 sets down the organization of the vital registration system more clearly. Second, the Ministry of Justice guidelines for implementation14 simplify the law for justice clerks and the public, and reflect the responsive nature of the bureaucracy. Third, the 2005 reforms for immediate implementation in 2006, supported by training programmes for justice clerks at the province, district and commune levels, also indicates a strong level of political support. In 2007, another positive step was the compilation of mortality statistics from registration data by the Ministry of Justice. This impetus for strengthening vital registration should continue through political support for reforms to improve intersectoral collaboration.

Public awareness and participation

We did not use direct community interaction to gather evidence on public awareness of responsibilities towards and perceived benefits from death registration. However, our discussions with registration personnel provided insight on possible barriers to public participation (Box 1), and corroborated results from similar qualitative research in Bavi district.23 The limited incentives for death registration were reflected by one citizen (as narrated by a justice clerk), who remarked, “I do not know what to do with the death certificate which only repeats my sad memories of the event. Further, I cannot go to work for the day, hence lose a day’s salary”. As a justice clerk noted in his description of a household visit to conduct the formalities of registration, “…death is a very sensitive [issue] and it is impossible for us to go and ask a family to register the death while they are grieving. We will be shouted at…”. Recording the cause of death may be a further obstacle, as described by another justice clerk who reported, “When we ask for the cause of death, they say, ‘my father’s death is my personal issue’”. The government should take these perceptions into account in efforts to develop culturally sensitive, streamlined procedures for death registration.

Box 1. Barriers to civil and vital statistics registration in Viet Nam.

Structural barriers

Geographic constraints

Limited staff leading to high workload and inefficient services

Inconsistent application of decree

Supporting identity documents sometimes not available

Inconvenient registration policies for non-residents

Inadequate publicity or awareness of registration responsibilities

Social barriers

Reporting period impinges upon burial and mourning customs

Travel costs, registration fees and loss of income for time spent pursuing registration

No perceived social benefit from death registration (as opposed to birth registration)

Sensitivity about reporting of cause of death

Creating community demand for death certificates for legal and social purposes would increase public support, and community sensitization has improved public participation. One justice clerk stated that his commune benefited from registration awareness campaigns. Public addresses during on-site registration camps have been successful, as has the incentive of 50 kg of rice for registering deaths within the 15-day deadline in several communes located in Hòa Bình (Malcolm MacDonald, personal communication, July 2008).

Discussion

In 2002, the Vietnamese Ministry of Health included several mortality indicators in its prescribed lists of essential health indicators at district, provincial and national levels: perinatal, infant and under-five mortality rates, maternal mortality ratios, leading causes of death, mortality rates from common infectious diseases and life expectancy at birth.24 A recent assessment of health information systems in Viet Nam identified two main sources of mortality statistics: the Ministry of Justice Vital Registration System and the Primary Vital Record System (health sector).25 The review identified problems with data from both sources. The Ministry of Justice system was inadequate at ascertaining causes of death, while the Primary Vital Record System was constrained by insufficient village health staff or their periodic rotation. This review mentioned two other potential data sources: the permanent residence registration system operated by the public security sector; and the population surveillance system operated by the General Office for Population and Family Planning (Ministry of Health). However, the former is dependent on the Ministry of Justice system for inputs on vital events, whereas the latter system focuses on data related to birth and family planning.

National vital registration systems are the ideal source for mortality statistics. The Ministry of Health plays a crucial role in improving vital registration, and should ensure that health staff are committed to the accurate reporting of births and deaths and ascertaining cause of death.26 The General Statistics Office could facilitate data compilation and management. A collaborative programme is needed to strengthen registration and statistical operations, preferably through an interagency coordination committee. The committee should develop a charter of responsibilities and actions based on the roles and needs of different stakeholders, particularly the Ministries of Justice and Health. Adequate intersectoral collaboration at the local level is essential to improve completeness of registration.

Previous efforts to assess civil registration and vital statistics systems were conducted through detailed questionnaires completed by national government officials,27 or through visits that focused on reviewing systemic aspects of vital registration.28 Our research method combined systems assessment with data evaluation and analyses to characterize the performance of the system with actual data. Our quantitative analyses found low completeness of adult death registration in all three provinces and lower-than-expected under-five mortality measures as features that provide a rough baseline assessment of system performance. We used qualitative methods to identify the reasons for under-registration of deaths. Fieldwork also determined that vital registration operations were consistent in all three provinces, indicating the potential for reforms to be simultaneously implemented across the country. Our findings, together with the recommendations listed in Table 3, exemplify how our assessment framework could be applied to develop practical solutions for improving vital registration in Viet Nam. In summary, vital events should be clearly defined within the legal framework, and the structure and organization of the system should ensure complete registration. In addition, the system should be appropriately designed to record events correctly, and statistical outputs should be timely and should accurately reflect the actual data.

Table 3. Recommendations to strengthen different elements of vital registration systems in Viet Nam.

| System attribute | Recommendations | |

|---|---|---|

| Legal framework | • Clear definitions of live births and fetal deaths in the civil code and professional guidelines | |

| • Registration of stillbirths mandated in the civil code | ||

| • Clear instructions in professional guidelines on registration of births, stillbirths and deaths | ||

| • Uniform instructions on registration of temporary residents and migrants | ||

| Structure and organization | • Active involvement of village headman and health staff as notifiers of vital events to the commune justice clerk to improve completeness of official death records | |

| • Health facilities periodically report institutional vital events directly to Ministry of Justice | ||

| • Responsibilities given to local health staff for ascertaining cause of deaths that occur at home | ||

| • Statistical agencies at district and provincial level facilitate data management and quality control | ||

| System design | • Implementation of international form of medical certificate of cause of death in health facilities | |

| • Design new form to support legal instructions for reporting of stillbirths | ||

| • Adoption of international perinatal death certificate for perinatal deaths in health facilities | ||

| • Use of international standard verbal autopsy protocols for ascertaining causes for deaths outside health facilities | ||

| • Formats for statistics on deaths by age, sex and cause according to international standards | ||

| Data management and quality control | • Introduction of International Classification of Diseases-based coding of underlying causes of death | |

| • Computerization of vital records | ||

| • Establishment of procedures for collation, verification and processing of vital statistics at each level | ||

| • Periodic evaluation of data quality according to standard criteria | ||

| Human resources | • Review of staff deployment for vital registration | |

| • Training programmes for registration staff, health personnel and statisticians to support reforms in structure, system design and data management processes | ||

| Political will and support | • Establishment of interagency coordination committee (including the Ministries of Justice and Health, the General Statistics Office and other stakeholders in civil registration and vital statistics) | |

| • Specified charter of activities, and dissemination of proceedings of committee meetings | ||

| • Workshops on registration reforms, data quality evaluation, analysis and interpretation for health bureaucrats and health policy analysts, to enhance political support for improvements in vital registration | ||

| Public awareness and participation | • Review of registration process to facilitate public participation | |

| • Publicity campaigns to highlight responsibilities towards and benefits from birth and death registration |

The first steps

Vital registration in Viet Nam could be improved by establishing a sentinel mortality surveillance system.29,30 This has also been recommended by the Ministry of Health as an interim measure for vital statistics.24 Towards this end a field research project is currently under way in a nationally representative sample of almost 200 communes, covering 2.6 million people. In each commune a justice clerk, health staff members and community representatives will collect data on deaths by age, sex and cause in 2009. Five medical universities are leading the implementation of locally adapted verbal autopsy methods, guided by community perceptions of death reporting and cause-of-death enquiry. These are the first steps towards strengthening vital registration in Viet Nam.

The demand for data from the health sector, donor agencies and the international community could stimulate interest and funding to continue improving the mortality statistics system. Utilization of mortality data by health planners, academics and researchers would accelerate this process. Adequate leadership combined with a strategic approach could help realize the goal of timely and reliable mortality statistics for Viet Nam in the foreseeable future.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the research was obtained from the Hanoi Medical University Review Board in Bio-Medical Research and the Behavioural and Social Sciences Ethical Review Committee at the University of Queensland. ■

Acknowledgements

We thank Dinh Thi Thanh Huyen for facilitating focus group discussions and key informant interviews and for translating specific documents from Vietnamese to English. We also thank Pham Nguyen Bang for transcription and decoding of recorded interviews in Vietnamese.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was undertaken with funding from WHO (Contract ID: OD/TS-07–00322) and the Atlantic Philanthropies (Grant No #14614).

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.UN Millennium Project. investing in development: a practical plan to achieve the millennium development goals. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2005. Available from: http://www.unmillenniumproject.org/reports/fullreport.htm [accessed on 28 September 2009].

- 2.WHO nomenclature regulations. In: International statistical classification of diseases and health related problems,10th revision, volume 1 Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993 pp. 1241-43. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahapatra P, Shibuya K, Lopez AD, Coullare F, Notzon FC, Rao C, et al. Civil registration systems and vital statistics: successes and missed opportunities. Lancet. 2007;370:1653–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World population prospects: the 2008 revision – highlights (Working paper no. ESA/P/WP.210). New York, NY: United Nations; 2009.

- 5.Mathers CD, Lopez AD, Murray CJL. The burden of disease and mortality by condition: Data, methods, and results for 2001. In: Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJL, eds. Global burden of disease and risk factors Washington, DC/New York, NY: The World Bank/Oxford University Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Byass P. Patterns of mortality in Bavi, Vietnam, 1999-2001. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2003;31:8–11. doi: 10.1080/14034950310015040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huong DL, Minh HV, Byass P. Applying verbal autopsy to determine cause of death in rural Vietnam. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2003;31:19–25. doi: 10.1080/14034950310015068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Principles and recommendations for a vital statistics system, revision 2 New York, NY: United Nations Statistical Commission; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pham TC. [About civil administration]. Hanoi: Politics Publishing House; 2004. Vietnamese. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rao C, Bradshaw D, Mathers CD. Improving death registration and statistics in developing countries: lessons from subSaharan Africa. Southern African Journal of Demography. 2004;9:81–91. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowland D. Demographic methods and concepts New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brass growth balance method. In: Manual X: indirect techniques for demographic estimation New York, NY: United Nations; 1983 pp. 139-146 (ST/ESA/SER.A/81).

- 13.Government of Viet Nam. Introduction to the civil code of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam, 2005 Hanoi: The Labour-Social Publishing House; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Justice. [Professional guidelines for civil registration and administration]. In Vietnamese. Hanoi: Justice Publishing House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Administrative infrastructures: centralized, decentralized and local civil registration systems, and the interface with vital statistics systems. In: Handbook on civil registration and vital statistics systems: management, operation and maintenance New York, NY: United Nations; 1998 pp. 4-15. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ministry of Justice. [New regulations for civil registration and administration]. In Vietnamese. Hanoi: Politics Publishing House; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mortality: guidelines for certification and rules for coding. In: International statistical classification of diseases and health related problems, 10th revision, volume 2: instruction manual Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. pp. 30-65.

- 18.Statistical presentation. In: International statistical classification of diseases and health related problems, 10th revision, volume 2: instruction manual Geneva: World Health Organization; 1993. pp. 124-38.

- 19.Demographic and Health Surveys. Vietnam 2002 Calverton, MD: ICF Macro; 2002. Available from: http://www.measuredhs.com/countries/country_main.cfm?ctry_id=56 [accessed on 28 September 2009].

- 20.WHO Statistical Information System. Vietnam: mortality and burden of disease Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/en/ [accessed on 28 September 2009].

- 21.Population and housing census Vietnam 1999 Hanoi: General Statistics Office; 1999. Available from: http://www.gso.gov.vn/default.aspx?tabid=503&ItemID=1841 [accessed on 28 September 2009].

- 22.Huy TQ, Long NH, Hoa DP, Byass P, Ericksson B. Validity and completeness of death reporting and registration in a rural district of Vietnam. Scand J Public Health Suppl. 2003;31:12–8. doi: 10.1080/14034950310015059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huy TQ, Johannson A, Long NH. Reasons for not reporting deaths: a qualitative study in rural Vietnam. World Health Popul. 2007;9:14–23. doi: 10.12927/whp.2007.18739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.List of essential health indicators issued under decision no. 2553/2002 QD-BYT Hanoi: Ministry of Health; 2002. Available from: http://soyte.angiang.gov.vn/xemtin.asp?cap=1&id=60 [accessed on 28 September 2009].

- 25.Vietnam health information system review and assessment: report submitted to Health Metrics Network, World Health Organization Hanoi: Ministry of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Handbook on civil registration and vital statistics systems: Information, education and communication New York, NY: United Nations; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Handbook on vital statistics systems and methods, volume 2: review of national practices (report no. ST/ESA/STAT/SER.F/35). New York, NY: United Nations; 1985.

- 28.Benjamin B. Vital registration systems in five developing countries: Honduras, Mexico, Philippines, Thailand, and Jamaica: a comparative study (report no. DHHS Publication no. (PHS) 81-1353). Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setel PW, Sankoh O, Rao C, Velkoff VA, Mathers C, Gonghuan Y, et al. Sample registration of vital events with verbal autopsy: a renewed commitment to measuring and monitoring vital statistics. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:611–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Begg S, Rao C, Lopez AD. Design options for sample-based mortality surveillance. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:1080–7. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]