Abstract

Extending coverage to migrant workers is a priority for China as it overhauls its health-care system. Cui Weiyuan reports.

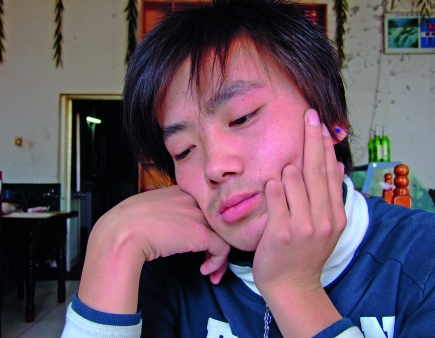

When 18-year-old factory worker Dou Huhai came down with a cold, after a 15-hour shift at a zipper factory on the outskirts of Beijing, he had “neither the money nor the time” to see a doctor so he just took some medicine. The following day, still drowsy from the medication, he caught his left hand in his punching machine.

The machine that snagged Dou’s hand crushed two of his fingers. He was taken to the county-town hospital, and then transferred to the Armed Police Hospital, where a doctor told him that it was going to be possible to salvage most of his fingers, but when he discovered that Dou could not pay for the operation, and had no insurance coverage – at least as far as he knew – the doctor performed a simple amputation. Dou’s boss paid, but when Dou demanded compensation he was fired. “I did not have a labour contract,” Dou says. “Nor do I have the health insurance through my employer. No one would hire you here, if you insisted on having one.”

Dou comes from a peasant family in Shaoyu Town, Xihe County, in China’s north-western Gansu Province and is one of China’s estimated 200 million migrant workers. Health coverage should now improve for people like him. Just nine days after Dou started work in the zipper factory in April 2009, the government announced plans to provide universal access to essential health care to all residents in China by 2020.

If fully implemented, the reform will spell the end of the market-based mechanisms that had been gradually introduced since the early 1980s, after 30 years of covering more than 90% of medical expenses for urban residents and providing basic, low-cost health-care services to the rural population.

The fact that Dou did not know if he had insurance coverage comes as no surprise to Wei Wei, the founder of Xiao Xiao Niao, a Beijing-based nongovernmental organization defending the few rights that migrant workers have. He says that migrant workers rarely know if they are insured and that this is partly why there are no reliable statistics on how many are covered. A survey carried out by the China Development Research Foundation back in 2000 revealed that fewer than 3% of migrant workers were covered by health insurance schemes, and those who were covered had only limited access to health-care services. Since then, the situation has improved somewhat. Now over 30 million migrant workers are covered by the Urban Employee Basic Health Insurance Scheme (URBMI), according to the Chinese Medical Insurance Association.

As a result of China’s 1978 economic reform, health-care coverage shrank dramatically. Among the rural population, it dropped to less than 10%. And even in the cities from the late 1970s to mid-1980s, people found themselves suddenly vulnerable as urban medical insurance ceased to cover the dependants of salaried workers and many workers were laid off owing to restructuring of state-owned enterprises in the early 1990s. The amount of health care that consumers had to pay for out of their own pockets rose sharply from just over 20% in 1980 to a high of 60% in 2000. Just as pernicious was the impact of reform on the supply side. Having previously benefited from state funding, hospitals suddenly had to survive on patient fees. Doctors at state-owned hospitals started prescribing medicines and treatment on the basis of their revenue-generating potential – both for themselves and the hospital – rather than for their clinical efficacy, a practice that continues today.

Since 2003, the government has focused on two main types of insurance: the New Rural Cooperative Medical Schemes (NRCMS), which were initiated in 2003 for rural populations; and the URBMI, first piloted in 88 cities in 2007.

These schemes are heavily subsidized with the government paying up to 80% of the premiums. According to Dr Lei Haichao, Director of Policy Research at the Ministry of Health, the NRCMS now covers 833 million of the rural population, while URBMI covers 337 million. Under the reform plan announced in April 2009, more than 90% of China’s 1.6 billion population will be covered by the NRCMS, URBMI or a third scheme called urban resident basic health insurance by 2011, up from 15% in 2003. By mid-2009, the government had invested 71.6 billion yuan (US$ 10.5 billion) in the health-care reform plan, according to the State Council’s Office of Health Care Reform.

This promises to change life for migrant workers who are among the most vulnerable members of China’s working population. Another migrant worker who has been affected by catastrophic health expenses is Liu Mei. Her son, Ma Jilei, became ill with ankylosing spondylitis in 2003. Since then, she and her husband have spent virtually all their earnings on his medical bills. “Some of them come to us for help with catastrophic medical expenditure because some accident happens, or some family member gets severely ill.” Wei says. “But we cannot help all of them.” Some money comes in from charities, but it is not enough. “Relying on charitable funds to solve the burden of health-care costs is as useful as using a glass of water to put out a fire on a whole cart of wood,” Wei says.

One of the main reasons for migrant workers’ vulnerability is the typically informal nature of their employment. China’s parliament, the National People’s Congress, recently passed a new labour law providing better protection to workers. But, according to Dr Tang Shenglan, health and poverty adviser at the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s)country office in Beijing, its enforcement has not been very effective. Many migrant workers are hired directly by small private companies, including unregulated ‘underground’ sweatshops. Others find a job through a contractor – more often than not somebody the migrant workers knows from his or her hometown. “Many construction workers find jobs this way,” Wei says. But even migrant workers hired by multinational companies struggle with insurance because of the fragmented regional nature of Chinese health-care financing. In recent years some migrant worker groups have advocated quitting insurance schemes altogether because coverage cannot be transferred when they move to a new region, Wei says.

This may now be changing. In July 2009, the Chinese Ministries of Health, Civil Affairs, Finance and Agriculture and the State Administration of Traditional Medicine made a joint statement regarding the health insurance of migrants. According to Tang, more and more multinational and national companies are now registering their migrant workers with health insurance schemes. There are also ongoing efforts to simplify reimbursement procedures. According to Lei from the Ministry of Health, current policy allows migrant workers to register in either the NRCMS or URBMI if they have formal employment contracts with the enterprises.

While the government struggles to fine-tune insurance coverage it must also address issues on the supply side, particularly hospital funding. At present, hospitals continue to operate on a fee-per-service model. Officially Chinese hospitals are limited in what they can charge for services, but are free to generate volume to boost revenue by over provision of services and medical products including medicines. A cardiovascular specialist at a leading Beijing hospital said that he was obliged to charge fees for procedures to augment his 1500 Yuan per month salary (US$ 220). He added that doctors at his hospital received a bonus depending on the income of different departments and on their position and contribution. In other words, the more procedures they performed – the most lucrative being the insertion of a stent in heart surgery – the more they took home in their pay check.

Inevitably this has led to uneasy doctor–patient relations. Yuan Jianping, an investor relations director in Beijing and one of the beneficiaries of China’s economic boom, expresses typical patient anxiety: “It seems to me that many doctors are treating patients [to] make their hospitals profitable,” she says.

Chinese authorities have been looking at payment options since the 1990s when diagnosis-related group (DRG) payment was first pushed by the National Development and Reform Commission. DRG is a system to classify hospital cases into one of approximately 500 groups, this standardization is used as a basis to calculate fees.

Dr Hongwen Zhao of WHO’s Department for Health System Governance and Service Delivery believes that as the broad outlines of hospital reform become clear, the payment method will also be sorted out. “Over the next three years the government will choose either a supply-side or demand-side financing model,” he says, adding, “A huge amount of technical work needs to be done.”

Tang adds that while alternative payment methods to fee-for-service methods to control medical costs, such as capitation and DRG, have been discussed in China for two decades, “there has been a lot of resistance from hospitals and other service providers to adopt these payment methods”. ■

Dou Huhai, a migrant worker who damaged his fingers in a workplace accident.

WHO/Cui Weiyuan

Liu Mei, a migrant worker. For the last few years, she and her husband have spent nearly all the money they have earned on their son’s medical bills.

WHO/Cui Weiyuan