Abstract

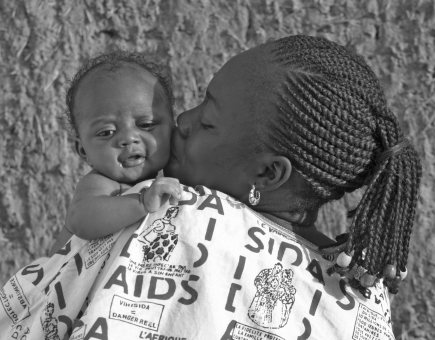

Despite emerging evidence that HIV-positive mothers should breastfeed to maximize their babies’ health prospects, South African health workers face a battle to change attitudes and habits. Lungi Langa reports.

Breastfeeding may be natural, but it is not always simple. Professor Anna Coutsoudis, of the Department of Paediatrics and Child Health at the University of the KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, says the problem begins in the first weeks of breastfeeding. “Health-care providers lack the skills needed to offer support and advice,” she says. “So when problems arise – cracked nipples, babies won’t suck and babies don’t seem satisfied – the mothers get bad advice. Then when they become discouraged, they are told to stop breastfeeding altogether and to give artificial substitutes.”

If the mother is HIV positive, more uncertainty is added. “Some counsellors are themselves confused about what is correct practice regarding HIV and feeding practices,” says Thelma Raqa, an antenatal counsellor based in Mowbray Maternity Hospital in Cape Town.

Until recently, the World Health Organization (WHO) advised HIV-positive mothers to avoid breastfeeding if they were able to afford, prepare and store formula milk safely. But research has since emerged, particularly from South Africa, that shows that a combination of exclusive breastfeeding and the use of antiretroviral treatment can significantly reduce the risk of transmitting HIV to babies through breastfeeding.

On 30 November 2009, WHO released new recommendations on infant feeding by HIV-positive mothers, based on this new evidence. For the first time, WHO is recommending that HIV-positive mothers or their infants take antiretroviral drugs throughout the period of breastfeeding and until the infant is 12 months old. This means that the child can benefit from breastfeeding with very little risk of becoming infected with HIV.

Prior research had shown that exclusive breastfeeding in the first six months of an infant's life was associated with a three- to fourfold decreased risk of HIV transmission compared to infants who were breastfed and also received other milks or foods.

Instrumental in guiding the new recommendations were two major African studies that announced their findings in July 2009 at the fifth International AIDS Society conference in Cape Town. The WHO-led Kesho Bora study found that giving HIV-positive mothers a combination of antiretrovirals during pregnancy, delivery and breastfeeding reduced the risk of HIV transmission to infants by 42%. The Breastfeeding Antiretroviral and Nutrition study held in Malawi also showed a risk of HIV transmission reduced to just 1.8% for infants given the antiretroviral drug nevirapine daily while breastfeeding for 6 months.

In spite of these findings it will be a challenge to change the ingrained culture of formula feeding in South Africa. Existing attitudes have been influenced by the country’s high HIV-prevalence – 18% of the adult population is HIV positive, according to 2008 estimates from the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. The 2003 South African Demographic Health Survey found that fewer than 12% of infants are exclusively breastfed during their first three months and this drops to 1.5% for infants aged between three and six months.

Some health workers themselves are yet to be convinced of the benefits of breastfeeding, even for mothers who aren’t HIV positive. “There exists the general idea that it is not important, that there is no critical reason to breastfeed, especially when you can formula feed,” says Linda Glynn, breastfeeding consultant at Mowbray Maternity Hospital in Cape Town. “Some [health workers] think breastfeeding is a waste of time and an inconvenience.” Yet, the risks of not breastfeeding often go unrecognized. Most children born to HIV-positive mothers and raised on formula do not die of AIDS but of under-nourishment, diarrhoea, pneumonia and other causes not related to HIV. Breastfeeding not only provides babies with the nutrients they need for optimal development but also gives babies the antibodies they need to protect them against some of these common but deadly illnesses.

WHO recommends that all mothers, regardless of their HIV status, practise exclusive breastfeeding – which means no other liquids or food are given – in the first six months. After six months, the baby should start on complementary foods. Mothers who are not infected with HIV should breastfeed until the infant is two years or older.

Penny Reimers, of the Department of Nursing at Durban University of Technology, says the greatest declines in breastfeeding have taken place in countries where formula milk has been distributed at no cost, South Africa being a prime example. Infant formula was distributed by national and local authorities and by local nongovernmental organizations to prevent the transmission of HIV from mother-to-child, an initiative which inevitably undermined breastfeeding. An unforeseen consequence of the campaign was that even mothers who were not HIV positive turned to formula, says Reimers.

One reason for the switch was a belief that formula was in some way superior to breast milk, a perception that Coutsoudis believes derives, at least in part, from “strong and dishonest” marketing campaigns that make unfounded claims that the formula milk contains special ingredients that improve baby’s health. “Mothers are not told the truth, that breast milk is infinitely better [for the infant] and that formula milk can be dangerous; that it is not always a sterile product and is easily contaminated,” Coutsoudis says.

But even without formula producers’ marketing campaigns, other pressures are at work. One is the changing role of women in South African society. More women are in paid work than 20 years ago and many struggle to fit breastfeeding into their routines. When Pato Banzi, an administration officer at the Magistrates’ Court in Wynberg, Cape Town, had her second son she was granted four months’ maternity leave in accordance with South African labour law, but then struggled when the time came to return to work. “I was lucky that I lived close to where I worked so I could drive home to feed him and rush back to work,” she says. Later she switched to expressing milk, which she conserved in bottles, but had to go into the company boardroom to do this in private. Deidre Zimri, operations manager for a transport company, did her expressing in the waiting room when no one was using it. Both Banzi and Zimri felt that four months’ maternity leave was not enough.

Louise Goosen, a breastfeeding consultant at Mowbray Maternity Hospital in Cape Town, says that “going back to work” is one of the most common reasons for stopping breastfeeding. But even for mothers who don’t have to juggle paid work while caring for their babies, switching to formula is a huge temptation simply because it is thought to be convenient. But even for mothers who don’t have to juggle paid work while caring for their babies, switching to formula is a huge temptation simply because it is thought to be convenient. “However we need to encourage and educate mums on the ease and importance of expressing their breast milk to give to baby while mum is at work so that baby can still get the best nutrition,” Goosen explains.

So what can be done to make it easier for women to choose the breastfeeding option? The government needs to convince industry to make it easy for mothers to carry on breastfeeding after returning to work, says Lulama Sigasana, a nutritionist working at Ikamva Labantu, a South African non-profit organization based in Cape Town. She also believes that mothers should be provided with space and time to express milk in private at work. She says the government could do more to communicate the message that breastfeeding is good. “There are already some [campaigns]” she says, noting the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative and World Breastfeeding Awareness week, held every August, but we need more programmes to boost breastfeeding uptake and continuation.

Sigasana thinks breastfeeding advocacy should also be directed to the people who may influence a woman’s decision to breastfeed, i.e. her partner and extended family. “In most households, what grandmother says goes,” she says. “If she says the mother must breastfeed, she feels she has no choice, but if she says formula, then formula it is. It’s no use educating mothers only. There need to be nationwide campaigns aimed at everyone.”

Coutsoudis agrees, saying advocacy programmes should be extended to society as a whole so that breastfeeding can again become the “natural way to feed a baby.” And it doesn’t help when many health workers are so quick to advise formula feeding, says Coutsoudis: “The representatives from formula companies visit [health workers] often, build good relationships, and market their products.”

Without their active support, how quickly can attitudes really change? One thing is certain: health professionals will be more likely to support the underlying message if they have a basic understanding of current research. As Sigasana puts it: “We need to make sure that people who interact with mothers are giving out the correct information.” ■

New evidence recommends HIV-positive mothers should breastfeed.

AVECC/H Vincent

It takes time to learn the techniques: young mother breastfeeding in Mowbray Maternity Hospital, Cape Town.

Louise Goosens/Mowbray Maternity Hospital, Cape Town