Abstract

HIV-serodiscordant relationships are those in which one partner is infected with HIV while the other is not. We investigated experiences of sexual violence among women in HIV discordant unions attending HIV post-test club services in Uganda. A volunteer sample of 26 women from three AIDS Information Centres in Uganda who reported having experienced sexual violence in a larger epidemiological study were interviewed, using the qualitative critical incident technique. Data were analysed using TEXTPACK, a software application for computer-assisted content analysis. Incidents of sexual violence narrated by the women included use of physical force and verbal threats. Overall, four themes that characterise the women’s experience of sexual violence emerged from the analysis: knowledge of HIV test results, prevalence of sexual violence, vulnerability and proprietary views and reactions to sexual violence. Alcohol abuse by the male partners was an important factor in the experience of sexual violence among the women. Their experiences evoked different reactions and feelings, including concern over the need to have children, fear of infection, desire to separate from their spouses/partners, helplessness, anger and suicidal tendencies. HIV counselling and testing centres should be supported with the capacity to address issues related to sexual violence for couples who are HIV discordant.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, women’s health, sexual violence, discordant status, gender-based violence

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2002) defines sexual violence as “any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, unwanted sexual comments or advances, or acts to traffic, or otherwise directed, against a person’s sexuality, using coercion by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting, including but not limited to home and work”. In addition to physical force, sexual violence includes psychological intimidation, threats of physical harm, of being dismissed from a job or of not obtaining a job that is sought (WHO, 2002). It may also occur when the victim is unable to give consent, for example, while drunk, drugged, asleep or mentally incapacitated (Garcia-Moreno, Jansen, Ellsberg, Heise, & Watts, 2006; WHO, 2002).

In 2006, WHO published results of a Multi-country Study on Domestic Violence and Women’s Health (Garcia-Moreno et al., 2006) conducted in 10 countries with more than 24,000 women. According to the study, the reported lifetime prevalence of sexual violence ranged from 15 to 71%, with six of the 10 countries reporting prevalence rates of 50-75%. Studies in sub-Saharan Africa (e.g., Rani, Bonu, & Diop-Sidibe, 2004) show that acceptance of wife beating for transgressing certain gender roles is widespread in many countries. In Uganda, the magnitude of sexual violence committed by men against women has long been noted as an issue of public health concern. In a 1995 study, Heise, Moore, and Toubia (1995) found that 22% of adult women in the country experienced sexual violence. Another population-based survey of women of reproductive age in a rural district in the country (Koenig et al., 2004) revealed a prevalence rate of 26.6% among women in sexually active relations. Data from the 2006 Uganda Demography and Health Survey (Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) and Macro International Inc., 2007) provides striking evidence of the growing burden of sexual violence in the country. One in four women reported that their first sexual intercourse was forced against their will. Seventy percentage of women and 60% of men agreed that wife beating was justifiable under certain circumstances.

Although sexual violence against women receives attention in many industrialised nations (Cherniak et al., 2005), it attracts comparatively less emphasis in developing countries, perhaps due to cultural factors and resource constraints (McMichael, Waters, & Volmink, 2005). Sexual violence against women may lead to infection with sexually transmitted diseases (Wingood, DiClemente, & Raj, 2000), unwanted pregnancies (Holmes, Resnick, Kilpatrick, & Best, 1996), chronic pelvic pain, premenstrual syndrome, gastrointestinal disorders and gynaecological and pregnancy-related complications (Jewkes, Sen, & Garcia-Moreno, 2002). It has also been associated with a range of mild to severe psychological effects (Ackard & Neumark-Sztainer, 2002; Faravelli, Giugni, Salvatori, & Ricca, 2004; Ystgaard, Hestetun, Loeb, & Mehlum, 2004) and fatalistic tendencies that predispose women to risky sexual behaviours and substance abuse problems (Bergen, 1995; Khanna, 2008).

Managing emotional and sexual intimacy can be challenging in HIV discordant relationships because of concerns about HIV transmission, the burden of initiating and maintaining safer sex, and the health status of the affected partner (van der Straten et al., 1998). These factors can negatively impact sexual desire and may lead to increased psychosexual problems that often result in, or escalate violence (Widom & Kuhns, 1996). Although several quantitative investigations of sexual violence and HIV/AIDS have been conducted in sub-Saharan Africa, very few have sought to examine the perspectives of women who experience such violence.

Methods

Design

We used the qualitative critical incident technique (CIT; Flanagan, 1954), an open-ended retrospective method of eliciting information on people’s actual encounters with a phenomenon of interest. As part of a larger epidemiological study, the aim was to gain a deeper understanding of the nature and contexts of the sexual violence experienced by women in HIV sero-discordant unions, who were attending three AIDS Information Centres (AICs) in Uganda.

Study setting and participants

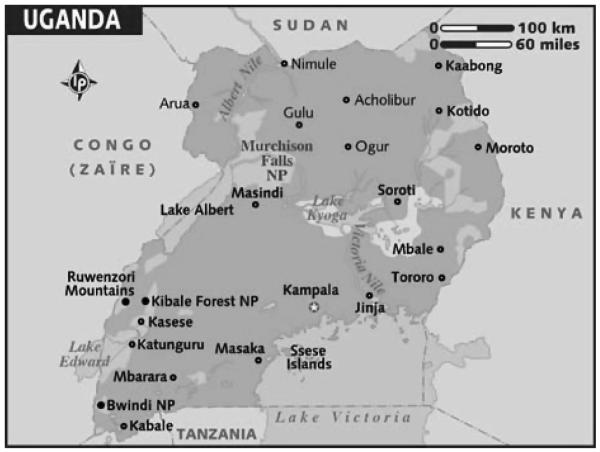

The three AICs are located in Kampala, Jinja and Mbale in Uganda (Figure 1). Founded in the early 1990s, the AICs offer individualised HIV counselling and testing, a wide range of reproductive health services, tuberculosis prevention and post-test club services (AIC, 2004; Painter, 2001). As of the end of 2004, the client base of Uganda’s AICs included 25,193 individuals for the Kampala branch, 8459 for Jinja branch, and 6707 for Mbale branch (AIC, 2004). In a preliminary epidemiological study to estimate the prevalence of sexual violence among women of HIV sero-discordant status at the three AICs, 100 women reported having experienced sexual violence. All 100 women were invited to participate in the qualitative critical incident study, and 26 (25%) consented. All study participants and their spouses/partners had previously received HIV antibody tests with their HIV serostatus disclosed to them. Average length of time between receipt of HIV serostatus result and the critical incident study was 10 months. Women, who volunteered to participate gave written informed consent, were assured of confidentiality, and interviewed by a trained and experienced counsellor at AIC on a one-to-one basis.

Figure 1.

Map of Uganda.

Source: Lonely Planet Maps http://www.lonelyplanet.com/maps/africa/uganda/

Ethical approval

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB), the Higher Degrees Research and Ethics Committee of Makerere University School of Public Health (Uganda) and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. All procedures followed WHO ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women (WHO, 2001).

Data collection instrument

We developed an interview guide based on the study aim, interviews with providers, review of the literature and open-ended responses from the preliminary epidemiological survey. Three Delphi reviews (Denzin & Lincoln, 2000) were completed to identify and clarify pertinent questions and to verify the validity of the guide. The guide was drafted in English and translated into Luganda by two independent bilingual translators. The Luganda version was later translated back to English by two other independent bilingual translators. The back translations were compared for consistency during the Delphi reviews. The final draft was piloted on five volunteer women of HIV-serodiscordant status who noted experience of sexual violence in the preliminary epidemiological survey. These women were excluded from the main study. The following are examples of questions covered by the guide: Did you experience sexual violence by your partner before taking your HIV test? Did you experience sexual abuse by your partner after taking your HIV test? If you suffered sexual violence, what was the nature of the violence? Did the sexual abuse increase in frequency after your HIV test? Under what circumstances did the sexual violence take place? Describe how the violence happened, and how you felt after the experience. Did you tell anyone about the incident before now? If yes, who did you tell? If you did not tell anyone, why did you not? Why do you think your partner perpetrates sexual violence? What do you suggest should be done to alleviate sexual violence?

Data collection

Data were collected in Luganda by a trained AIC counsellor. The interviews lasted an average of one hour per respondent and were conducted in private rooms in the AICs, with referrals made as needed for counselling and medical services within the AIC. This was a one-time data collection with no follow up interviews. All interviews were audio recorded with the permission of respondents and transcribed verbatim.

Data analyses

Each interview was transcribed by a trained field worker, carefully reviewed for accuracy, and analysed using TEXTPACK, version 7.5 (Mohler & Zuell, 1998). Transcripts of the interviews were coded and classified according to a user dictionary that was made. We generated tabulations with category frequencies, category sequences and emerging themes. We then identified critical incidents experienced by each respondent, namely, the different components of sexual violence perpetrated against them by their spouse/partner post-voluntary HIV counselling and testing. These incidents were then arranged into larger categories and themes.

Results

Twenty-one of the 26 women were married and five were co-habiting. A majority (20 out of the 26 women) had educational status above the secondary school level. About half were HIV negative (and their male partners, HIV positive), and the other half were HIV positive (and their male partners, HIV negative). All 26 participants narrated how their spouse/partner used physical force and verbal threats, slapping, kicking, shouting/yelling and hands being held down, to obtain sexual intercourse from them against their will. About two-thirds of the women admitted that sexual violence was present in their relationship prior to knowledge of their HIV serostatus, but that the violence increased at least twofold after.

Twenty of the women had told someone about the incident prior the interviews. Persons to whom they reported the incidents included: their parents, the perpetrator’s parents, friends, sisters, brothers, doctor and church pastor. None of the victims reported their experience to the law enforcement authority. The six that did not mention their experience to any one said it was difficult for them to open up because they felt ashamed; three said they thought the perpetrator would change with time and two feared that they might be put out of the home. Overall, women’s experiences with sexual violence after learning that they were living in HIV discordant relationships can be grouped into four themes (Table 1): (1) knowledge of HIV test results; (2) prevalence of sexual violence; (3) vulnerability and proprietary views; and (4) reactions to sexual violence.

Table 1.

Summary of themes and related categories

| Themes | Categories |

|---|---|

| 1. The knowledge of the HIV test results | Alcohol intoxication |

| Misunderstandings | |

| Arguments | |

| Quarrels | |

| Jealousy | |

| Intention of infecting the spouse/partner with HIV | |

| Use of physical force, verbal threats, slapped, beaten, kicked, shouted or yelled at, and held down | |

| Seeking separation | |

| Suspicion of infidelity | |

| HIV negative test result automatically becoming positive with time | |

| Threat of not begetting children because of early death | |

| 2. Prevalence of sexual violence | High prevalence of sexual violence prior to HIV test |

| Increased frequency of sexual violence after disclosure of test result | |

| 3. Vulnerability and proprietary | Dependence on the partner |

| Fear of the man acquiring HIV infection | |

| 4. Reactions to sexual violence | Fear of the victim acquiring HIV infection |

| Pain and bleeding | |

| Annoyance and helplessness | |

| Suicidal tendency | |

| Feeling stressed and mentally tortured | |

| Wanting to separate |

Theme 1: knowledge of HIV test results

Knowledge of HIV positive test results for either a woman or her male partner resulted in, or increased the burden of sexual violence against women in the study. A HIV negative woman whose partner was HIV positive (F-M+) aged 55 years narrated, “The moment we came back from the testing centre my husband was very annoyed and furious. After we received our HIV test results, he was positive and I was negative. He then started to drink heavily. He would come back home drunk and rape me”. Alcohol intoxication featured very prominently in the women’s narratives regarding their experiences of sexual violence. In describing one critical incident, an F-M+ respondent aged 39 years stated, “After we had gone for an HIV test and he tested positive, he started drinking carelessly...Whenever I refused to give him sex he would beat me when he is drunk. But I cannot tell what the intention of my husband was by forcing me into unprotected sex. This always happens when he came home after heavy drinking”.

Following the disclosure of their HIV serostatus, some women who sought protected sex through use of condoms were sexually abused by their spouse/partner after becoming embroiled in arguments. An F-M+ respondent aged 28 years explained, “So if I ask him to use a condom he slaps me and rapes me. I think he wants me to contract the disease. He is always quarrelling with me as to why I am not HIV positive. So after having misunderstandings and arguments I always do not feel free to have sex, but he forces me”. There is a common belief among those in F-M+ relationship that their partners want to deliberately infect them out of frustration, or perhaps to then turn around and accuse them of having infected them, a more culturally believable scenario. An F-M+ respondent aged 33 years described her experiences thus, “He feels very bad knowing that he is HIV positive and I am not. I think his intention was to make sure that I get the disease; so he could then say that I infected him. The sexual abuse took place under sadistic intentions, and also under the influence of alcohol. I think he also thought that doing all that he was doing would stop me from having extra-marital sexual affairs”.

When women were HIV positive in a discordant relationship, they were victimised by their partners as a result of suspicion that HIV infection got into the relationship as a result of their infidelity. An HIV positive woman (aged 22 years) whose partner was HIV negative (F+M-) stated, “It is because he believes I must have contracted HIV from other men during extra-marital sex”. For some couples, according to the women, this knowledge resulted in men perpetrating sexual violence in a bid to frustrate their partner into seeking separation. One F+M- aged 47 years narrated how her husband wanted her to leave him after the disclosure of the test results: “He thinks I might do something to infect him also; therefore he is trying to see that I leave his house”.

There was also a common belief among F+M- women that their partner believed he was either already infected or soon would be. An F+M- respondent aged 43 years stated, “It is because he thinks that even if he is HIV negative now, he will eventually become positive, so he wants sex without a condom”. One woman narrated that her husband perceived the presence of HIV in the relationship as a threat to having children, and as a result forced her to have sexual intercourse with him. An F+M- respondent aged 28 years explained thus, “His argument was that although he is HIV negative, he believes that he is HIV positive and that we should have at least two children before we die”.

Theme 2: impact of being in a discordant relationship on frequency of sexual violence

Among some couples who did not have prior history of sexual violence, victimisation of the woman by the man ensued after it became known that they were living in a HIV discordant union. An F+M- respondent aged 43 years stated, “Yes, the sexual violence which used not to be there started and increased in frequency over time after the disclosure of our test results. It started by him being rude to me, then it reached a stage whereby every time he wants sex, he would use force to get me to play sex with him against my will, especially when he was drunk”. Those who reported the existence of violence in their relationships prior to knowledge of their HIV status noted that the frequency increased at least twofold after the positive HIV result.

Theme 3: vulnerability and proprietary views

The respondents viewed themselves as being vulnerable or dependent on the men. Some women described relative physical weakness, economic and social dependence on their partner as contributory factors to violence. An F-M+ respondent aged 27 years narrated, “Because he has given up about life, he knows that I am negative so he feels jealous that another man will take me. So, since I am weaker than him he can rape me successfully. He even knows that I depend on him so I cannot leave him”. Based on the chain of events at the time of victimisation, some women viewed men as having proprietary rights over them. An F-M+ respondent aged 20 years described her experiences as the following: “One time he came home drunk and found me in bed. He then wanted sex but I asked him to use a condom. He then said bad things about me being his property and threatened to beat me if I said another word. He then played sex with me in a rough way. I felt pain and bitterness in my heart. I am helpless in this situation. Once you are married to a man you cannot deny him sex even if he is HIV positive. You cannot even force him to practice safe sex by using a condom if he does not want to. The dowry that he has paid as settlement for the customary marriage gives him ownership over you and authority to make decisions on sex in the relationship”.

Theme 4: reactions to sexual violence

The experience of sexual violence by women in HIV discordant relationships evoked different reactions and feelings among the victims. An F-M+ respondent aged 31 years described how frustrated she was with her husband’s violent behaviour and how she wanted to leave him: “The sexual abuse happened by my partner forcing me into sex without using a condom. This always made me feel stressed and I wanted to separate from him but I couldn’t because of my children. But now I have to decide because I don’t think he will change his ways. I am always mentally tortured”. Women often experienced fear at either possible infection or getting their partners infected. An F-M+ respondent aged 36 years explained, “One day when he came home drunk and after eating food he asked me for sex. I told him that I will not accept until he puts on a condom. He ended up slapping and kicking me. I was helpless and weak so I gave in. Now I fear that I am infected with HIV”. An F+M- respondent aged 24 years expressed how she feared that her partner could acquire HIV infection after he threatened and forced her into unprotected sex. She stated, “He would come back home and then during bedtime he would ask for sex. If I tell him to use a condom he would hold my hands on the bed and rape me. I was always worried, thinking that he would become positive because of not using a condom”.

Threats from men and the unwanted sexual intercourse itself evoked pain, bleeding, feelings of helplessness, annoyance and suicidal tendencies. An F-M+ respondent aged 28 years described how she wanted to commit suicide after having been exposed to sexual violence: “He threatened to beat me so he ended up playing sex with me and I was bleeding and in pain afterwards. I ended up feeling helpless and annoyed. This happened after the HIV test found him positive and I was negative. He slapped me and used force to get me into sex when I asked him to use a condom. After he raped me I felt like committing suicide. I was helpless”. Sexual violence was quite a humiliating experience to women in the study, leaving them feeling harassed and not able to defend themselves. An F-M+ respondent aged 25 years stated, “Whenever my husband came back drunk, I expected a fight from him and whenever we got to bed he could just force me to have sex with him. I always felt harassed and humiliated since I was not able to fight for myself”.

In many cases, sexual abuse among the women starts with the partner coming home drunk and demanding sex, which the spouse/partner denies because of fear of HIV transmission in the absence of protective measures, leading to sexual abuse that may involve use of physical force, verbal threats, slapping, beating, kicking, being shouted or yelled at or being held down. The context of most of the incidents was characterised by the perpetrator having been intoxicated with alcohol. In many incidents, the victim had suggested protected sex using a condom, while in several incidents both the victim and the perpetrator were embroiled in an argument or a misunderstanding. Accusations of infidelity also featured prominently in the women’s narratives.

Discussion

This study revealed that in the context of Uganda, sexual violence against women was fairly common, and heightened by the revelation of a couple’s discordant HIV serostatus irrespective of which partner was HIV positive. The most common form of sexual violence reported by women in HIV discordant unions was use of physical force, followed by verbal threats. These women suffered pain as a result of bodily injuries, some reported bleeding while others were bitter, felt exasperation as a result of their helplessness, and others developed suicidal tendencies. These findings underscore the reality that sexual violence against women has far-reaching consequences that may be physical (Holmes et al., 1996; Jewkes et al., 2002; Wingood et al., 2000), psychological (Ackard & Neumark-Sztainer, 2002; Faravelli et al., 2004; Ystgaard et al., 2004) or social (Maman et al., 2002).

The women’s fear of HIV transmission and the subsequent demand for use of condoms played a big role in the perpetuation of sexual violence. Thus, the suspicion of infidelity with subsequent apportioning of blame as to who brought the HIV infection into the relationship played an important role in propagating sexual violence against women. Being younger and often physically weaker, as well as being economically dependent on the male partners hindered the women’s ability to resist sexual advances of partners perceived to be at high risk of transmitting or getting infected with HIV. These findings are in agreement with those of an earlier study conducted in Uganda which revealed that women who venture into sexual relationships at an early age have a high risk of experiencing violence, and that economic dependence prevents women from seeking redress against, or separation from, abusive male partners (Koenig et al., 2003).

Alcohol intoxication was described as a major contributing factor to sexual violence against women in this study. This is supported by a study in South Africa (Dunkle et al., 2004) which reported that women whose partners drank alcohol before sex experienced violence two times more than their counter parts with non-drinking partners. Out of anger and frustration at their spouse/partner’s HIV negative serostatus, some men perpetuated sexual violence in order to infect their female partners with HIV. This highlights a serious need for couple counselling that includes issues pertaining to sexual violence pre and post-HIV testing. It also calls for enforceable legislation to deter individuals who deliberately or maliciously propagate sexual transmission of HIV. Situations where men insist on having unprotected sex with their spouses in the context of HIV discordance in the hope of having children who would succeed them before they succumb to HIV/AIDS (Homsy et al., 2006) may represent a valid emotional reaction in the cultural context of the study setting and should be addressed pre and post-testing by HIV/AIDS counsellors.

Although a majority of the women shared their experience of sexual violence with someone, none reported it to the law enforcement authority. This is in conformity with the findings of other studies, where it was reported that abuse is most commonly reported to non-authority figures (Fisher et al., 2003). This underscores the women’s lack of confidence in such institutions as the police and the judiciary in Uganda. In Uganda and many other less developed countries, sexual violence often is not punished by the justice system. The culture of Uganda and many other sub-Saharan African countries limits women’s ability to negotiate sexual decisions and behaviour, leading to their increased vulnerability (Wolff, Blanc, & Gage, 2000), and their feelings of helplessness as revealed in this study. The belief in Uganda that a woman is the property of the husband and the failure of authorities to treat sexual violence as a criminal offence discourages reporting of sexual violence and makes leaving abusive relationships difficult, thereby exacerbating the abuse (Human Rights Watch, 2003).

Although the findings of this study are specific to women in HIV discordant unions attending post-test club services at AICs in Uganda, the major advantage of the use of the qualitative approach is that it allowed for an in-depth exploration of the lived experiences of these women, which is not possible with traditional quantitative methods. However, this study is not free from limitations. Most notably, the results relied solely on self-reports. However, since sexual violence does not have social desirability, it was likely that the reports of the women represented actual experiences of sexual violence associated with their HIV status. It is also important to note that the perspectives of men were not considered since men were not included. There is no justification for men in HIV sero-discordant unions to perpetrate violence against their female partners. However, perspectives of the men regarding the motivation for their behaviours would be important to place the reported incidents in gender-specific context. Unfortunately, this phase of our study did not include male respondents as there was concern that this might heighten the risk of violence against the women.

In the light of the evidence from this study, it is important to strengthen the capacity of HIV counselling testing professionals in identifying and managing sexual violence. In line with the WHO (2006) recommendation for addressing violence against women, counselling protocol at the AICs should include issues pertaining to sexual violence in the context of HIV sero-discordance, HIV testing centres should provide appropriate information on reproductive options for couples who are HIV discordant. Referral systems should link couples with counselling services on sexual violence and health units where services for reproductive options for couples who are HIV discordant are available.

At the larger institutional level, prevention efforts would involve awareness creation, sensitisation and strengthening of the capacity of multidisciplinary institutions, such as the police, judiciary, human rights, health care, religious organisations, women’s groups and research organisations to respond to sexual violence. Finally, further research is needed to examine men’s perspective on the correlates of sexual violence in the context of HIV sero-discordance, since this will help to establish a more gender balanced perspective on the issue.

References

- Ackard DM, Neumark-Sztainer D. Date violence and date rape among adolescents: Associations with disordered eating behaviors and psychological health. Child Abuse and Neglect. 2002;26:455–473. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00322-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIDS Information centre (AIC) AIDS information centre 2004 annual report. Author; Kampala, Uganda: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bergen RK. Surviving wife rape: How women define and cope with the violence. Violence against Women. 1995;1(2):117–138. doi: 10.1177/1077801295001002002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherniak D, Grant L, Mason R, Moore B, Pellizari R, IPV Working Group. Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists of Canada Intimate partner violence consensus statement. Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Canada. 2005;27:365–418. doi: 10.1016/s1701-2163(16)30465-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. Sage; Newbury, CA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, Gray GE, McIntryre JA, Harlow SD. Gender-based violence, relationship power, and risk of HIV infection in women attending antenatal clinics in South Africa. Lancet. 2004;363:1415–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faravelli C, Giugni A, Salvatori S, Ricca V. Psychopathology after rape. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:1483–1485. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.8.1483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Daigle LE, Cullen FT, Turner MG. Reporting sexual victimization to the police and others: Results from a national-level study of college women. Criminal Justice Behavior. 2003;30:6–38. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan JC. The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin. 1954;51:327–358. doi: 10.1037/h0061470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, Heise L, Watts CH. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: Findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006;368:1260–1269. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heise L, Moore K, Toubia N. Sexual coercion and reproductive health: A focus on research. The Population Council; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Kilpatrick DG, Best CL. Rape-related pregnancy: Estimates and descriptive characteristics from a national sample of women. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1996;175:320–324. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homsy J, Kalamya JN, Obonyo J, Ojwang J, Mugumya R, Opio C, et al. Routine intrapartum HIV counselling and testing for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in a rural Ugandan hospital. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 2006;42:149–154. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225032.52766.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Just die quietly: Domestic violence and women’s vulnerability to HIV in Uganda. 15 A. Vol. 15. Author; New York: 2003. Human Rights Watch. [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R, Sen P, Garcia-Moreno C. Sexual violence. In: Krug EG, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. pp. 213–239. Available at: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/world_report/en/summary_en.pdf Cited: March 24, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Khanna R. Communal violence in Gujarat, India: Impact of sexual violence and responsibilities of the health care system. Reproductive Health Matters. 2008;16(31):142–152. doi: 10.1016/S0968-8080(08)31357-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, Nalugoda F, Kiwanuka N, Wabwire-Mangen F, et al. Coercive sex in rural Uganda: Prevalence and associated risk factors. Social Science & Medicine. 2004;58(4):787–798. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(03)00244-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig MA, Lutalo T, Zhao F, Nalugoda F, Wabwire-Mangen F, Kiwanuka N, et al. Domestic violence in rural Uganda: Evidence from a community-based study. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2003;81:53–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maman S, Mbwambo JK, Hogan NM, Kilonzo GP, Campbell JC, Weiss E, et al. HIV-positive women report more lifetime partner violence: Findings from a voluntary counselling and testing clinic in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92:1331–1337. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.8.1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMichael C, Waters E, Volmink J. Evidence-based public health: What does it offer developing countries? Journal of Public Health (Oxford England) 2005;27:215–221. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdi024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler PP, Zuell C. TEXTPACK. ZUMA.; Mannheim, Germany: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Painter TM. Voluntary counselling and testing for couples: A high-level intervention for HIV/AIDS prevention in Sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science & Medicine. 2001;53:1397–1411. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rani M, Bonu S, Diop-Sidibe N. An empirical investigation of attitudes towards wife-beating among men and women in seven sub-Saharan African countries. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2004;8(3):116–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UBOS and Macro International Inc. Uganda demographic and health survey 2006. Author; Calverton, MD: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- van der Straten A, King R, Grinstead O, Vittinghoff E, Serufilira A, Allen S. Sexual coercion, physical violence, and HIV infection among women in steady relationships in Kigali, Rwanda. AIDS and Behaviour. 1998;2:61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS, Kuhns JB. Childhood victimization and subsequent risk for promiscuity, prostitution, and teenage pregnancy: A prospective study. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86:1607–1612. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.11.1607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood G, DiClemente R, Raj A. Adverse consequences of intimate partner abuse among women in non-urban domestic violence shelters. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2000;19:270–275. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(00)00228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff B, Blanc AK, Gage AJ. Who decides? Women’s status and negotiation of sex in Uganda. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2000;2:303–322. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Author; Geneva, Switzerland: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . World report on sexual violence and health. Author; Geneva, Switzerland: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . Addressing violence against women in HIV testing and counselling: A meeting report. Author; Geneva, Switzerland: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ystgaard M, Hestetun I, Loeb M, Mehlum L. Is there a specific relationship between childhood sexual and physical abuse and repeated suicidal behaviour? Child Abuse and Neglect. 2004;28:863–875. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]