Abstract

Angiotensin II (Ang II) stimulates protein synthesis by activating spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and DNA synthesis through epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) transactivation in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). This study was conducted to determine whether Syk mediates Ang II-induced migration of aortic VSMCs using a scratch wound approach. Treatment with Ang II (200 nM) for 24 h increased VSMC migration by 1.56 ± 0.14-fold. Ang II-induced VSMC migration and Syk phosphorylation as determined by Western blot analysis were minimized by the Syk inhibitor piceatannol (10 μM) and by transfecting VSMCs with dominant-negative but not wild-type Syk plasmid. Ang II-induced VSMC migration and Syk phosphorylation were attenuated by inhibitors of c-Src [4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine (PP2)], p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) [4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole (SB202190)], and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) 1/2 [1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(2-aminophenylthio) butadiene (U0126)]. SB202190 attenuated p38 MAPK and c-Src but not ERK1/2 phosphorylation, indicating that p38 MAPK acts upstream of c-Src and Syk. The c-Src inhibitor PP2 attenuated Syk and ERK1/2 phosphorylation, suggesting that c-Src acts upstream of Syk and ERK1/2. Ang II- and epidermal growth factor (EGF)-induced VSMC migration and EGFR phosphorylation were inhibited by the EGFR blocker 4-(3-chloroanilino)-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline (AG1478) (2 μM). Neither the Syk inhibitor piceatannol nor the dominant-negative Syk mutant altered EGF-induced cell migration or Ang II- and EGF-induced EGFR phosphorylation. The c-Src inhibitor PP2 diminished EGF-induced VSMC migration and EGFR, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK phosphorylation. The ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 (10 μM) attenuated EGF-induced cell migration and ERK1/2 but not EGFR phosphorylation. These data suggest that Ang II stimulates VSMC migration via p38 MAPK-activated c-Src through Syk and via EGFR transactivation through ERK1/2 and partly through p38 MAPK.

Ang II, one of the major biologically active components of the renin-angiotensin system, produces vascular smooth muscle contractions (VSMCs) and contributes to the maintenance of sodium and water homeostasis (Navar, 1997; Touyz, 2003). The increased levels of Ang II contribute to the development of hypertension, heart failure, atherosclerosis, and restenosis after vascular injury (Rakugi et al., 1994; Feng et al., 2001; Weiss et al., 2001; Kobori et al., 2007). These pathophysiological effects of Ang II have been attributed to remodeling of cardiovascular tissues consequent to cytoskeleton rearrangement, activation of inflammatory cells, and migration and growth of VSMCs and cardiac cells (Gibbons et al., 1992; Sadoshima and Izumo, 1993; Weber et al., 1994; Brilla et al, 1995; Suzuki et al., 2003; de Cavanagh et al., 2009). The effects of Ang II on VSMC growth or migration are mediated via angiotensin 1 receptors through production of reactive oxygen species and activation of one or more serine-threonine and tyrosine kinases including mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (Touyz and Schiffrin, 2000; Touyz, 2004; Clempus and Griendling, 2006), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2), p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK), and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (c-JNK) (Servant et al., 1996; Natarajan et al., 1999; Xi et al., 1999; Kyaw et al., 2004; Ohtsu et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2007) and the focal adhesion kinase family, protein tyrosine kinase, proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2 (Pyk2), and c-Src, respectively (Eguchi et al., 1998, 1999, 2001; Rocic and Lucchesi, 2001; Touyz et al., 2001; Saito et al., 2002; Kyaw et al., 2004).

Ang II-induced VSMC migration by ERK1/2 activation has been reported to be mediated by c-Src (Kyaw et al., 2004). However, Ang II via c-Src stimulates Ca2+-dependent protein-kinase related protein kinase associated substrate that promotes VSMC migration by activating c-JNK (Kyaw et al., 2004). p38 MAPK also contributes to Ang II-induced migration of VSMCs via phosphorylation of heat shock protein 27 (Lee et al., 2007). Involvement of a metalloprotease that stimulates the release of heparin-binding EGF from its precursor has been implicated in Ang II-induced VSMC migration through transactivation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (Saito et al., 2002). Ang II via transactivation of EGFR results in increased activities of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK but not of c-JNK in smooth muscle cells (Eguchi et al., 2001). Proline-rich tyrosine kinase 2-activated c-Src has been proposed to promote EGFR transactivation by Ang II in VSMCs (Eguchi et al., 1999). We have recently shown that Ang II activates c-Src through p38 MAPK that in turn increases the activity of spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and results in increased protein synthesis, whereas Ang II stimulates DNA synthesis via transactivation of EGFR (Yaghini et al., 2007). The present study was conducted to determine whether Ang II-stimulated VSMC migration is mediated by p38 MAPK-activated c-Src via Syk activation and/or EGFR transactivation. The results of this study show that Ang II-induced VSMC migration is mediated by p38 MAPK-activated c-Src via both Syk activation and EGFR transactivation.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

Phospho-Syk (Tyr-525/526), phospho-Src (Tyr-416), phospho-p44/42 MAPK, phospho-tyrosine, Syk, Src, p44/42 MAPK, and p38 MAPK antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA). Anti-α-actin smooth muscle antibody and AG1478 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Secondary rabbit or mouse IgG antibodies were obtained from GE Healthcare (Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK). Human angiotensin II (H-Asp-Arg-Val-Tyr-Ile-His-Pro-Phe-OH) and EGF were purchased from Bachem Biosciences (King of Prussia, PA). Piceatannol (trans-3,3′-4,5′-tetrahydroxy-stilbene), SB202190, U0126, and PP2 were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Fetal bovine serum, cell medium 199, penicillin/streptomycin, amphotericin B and trypsin were obtained from Mediatech Inc. (Manassas, VA). The protein assay dye was from Bio-Rad Laboratories (Hercules, CA) and SuperSignal WestPico chemiluminescent substrate was purchased from Pierce Biotechnology (Rockford, IL).

Culture of VSMCs.

All experiments were performed according to the protocols approved by our Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, 1996). Male Sprague-Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 250 to 350 g were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Abbott Laboratories, North Chicago, IL), and their thoracic aortas were rapidly excised. VSMCs were isolated and cultured as described previously (Uddin et al., 1998). Cultured cells were maintained under 5% CO2 in medium 199 with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% penicillin/streptomycin, and 0.01% amphotericin B at 37°C. Cells between four and eight passages were made quiescent for 24 h with serum-free medium 199 before exposure to various inhibitors in all experiments. A trypan blue exclusion assay revealed no changes in viability of VSMCs after treatment with inhibitors, Ang II, or EGF or transfection with wild-type or dominant-negative Syk plasmids.

Cell Migration Assay (Wound Healing Technique).

VSMC migration was determined in six-well plates using the scratch wound approach as described previously (Waters and Savla, 1999). In brief, 80 to 100% confluent VSMCs plates were scraped with a sterile plastic pipette tip across the diameter of each well to produce 1- to 1.5-mm-wide wounds. Cells were rinsed twice with serum-free medium 199 to remove cellular debris, and images were obtained at the initial time of wounding (0 h) using a Nikon TE300 inverted microscope equipped with a CoolSnap FX charge-coupled device camera (Roper Scientific, Trenton, NJ), an Optiscan ES102 motorized stage system (Prior Scientific, Rockland, MA), and MetaMorph image analysis software (Universal Imaging, Downingtown, PA). Cells were then treated with various inhibitors or their vehicles for 30 min and exposed to Ang II (200 nM), EGF (100 ng/ml), or their vehicle. Images were collected by programming the x, y, and z coordinates for each wound location, which enabled the stage to return to the exact location of the original wound throughout the migration experiments. Wound area measurements were averaged from three fields of the same well, using the National Institutes of Health ImageJ 1.6 program, and mean values obtained were taken as single data points. Data are presented as the ratio of the difference in the area covered by the cells at 0 and 24 h to the area at 0 h as 100% (control). The effect of various agents on the areas covered by cells was calculated and is presented as a percentage of change compared with control.

Transfection of VSMC with Plasmids.

All transfection experiments were performed according to the procedure described previously (Yaghini et al., 2007). Subconfluent VSMCs were transiently transfected with empty vector (pALTERMAX) alone, wild-type (WT) Syk, or dominant-negative (DN) (Y525F/Y526F) Syk (kindly provided by Dr. H. Band, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) using Effectene transfection reagent (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) in a ratio of 25 μl of Effectene to 1 μg of plasmid in medium 199 containing 5% fetal bovine serum for 48 h according to the manufacturer's instructions. For migration assays, the transfected cells in six-well plates were scraped with a sterile plastic pipette tip across the diameter of each well to produce wounds of 1 to 1.5 mm in width, and then the wells were washed and the wounded area was measured by microscopy at 0 h and after 24 h of treatment with Ang II or its vehicle. To determine the activity of various kinases by measuring their phosphorylation, another set of transfected cells were exposed to Ang II (200 nM) or EGF (100 ng/ml) or its vehicle for 10 min. Then the cells were scraped, washed with phosphate-buffered saline, lysed, and subjected to SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blot analysis.

Western Blotting.

VSMCs were dispersed into lysis buffer (1% IGEPAL CA-630, 1 M Tris, 1 M NaCl, 2.5 mg/ml deoxycholic acid, 1 M EDTA, 1 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mg/ml p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 10 μg/ml leupeptin). The lysed cells were sonicated and centrifuged, and protein concentration was determined using a Bradford assay. Equal amounts of protein (20–40 μg) were resolved in and separated in 8% Tris-glycine SDS-polyacrylamide gel by electrophoresis and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. The blots were then blocked with 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline-Tween (1×) and incubated with primary antibodies (1:500–1:1000) overnight at 4°C. Blots were then washed with Tris-buffered saline-Tween (1×), exposed to their respective secondary antibodies (1:1000–1:2000) and developed using Supersignal WestPico chemiluminescent substrate. Densitometric analysis of phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated protein bands was performed using National Institutes of Health ImageJ software. The ratios of phosphorylated to nonphosphorylated protein bands from three experiments were determined and then were normalized with that obtained with vehicle or inhibitor in the presence or absence of Ang II or EGF.

Statistical Analysis.

The data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance; an unpaired Student's t test was used to determine the difference between Ang II- and EGF-treated and untreated groups in the presence or absence of inhibitors. Comparisons between mean values were made using analysis of variance and Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test with the values of at least three different experiments for each treatment performed on different batches of cells (prepared from six animals) and expressed as the mean ± S.E. p < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Angiotensin II-Stimulated VSMC Migration Is Mediated by Syk Through p38 MAPK-Activated c-Src.

We previously reported that Syk is expressed in VSMCs and is activated by Ang II through p38 MAPK-activated c-Src and mediates the effect of Ang II on protein synthesis (Yaghini et al., 2007). On the other hand, Ang II-induced DNA synthesis was mediated through EGFR transactivation (Yaghini et al., 2007). To determine whether p38 MAPK-activated c-Src mediates VSMC migration via Syk and/or EGFR transactivation, we examined the effect of Syk, c-Src, and p38 MAPK inhibitors on VSMC migration and phosphorylation of these kinases on Ang II- and EGF-induced VSMC migration by using the wound-healing method. Ang II (200 nM) produced a time-dependent increase in wound healing of VSMCs. However, the maximal increase (1.56 ± 0.14-fold) in wound healing of VSMCs was observed at 24 h, and this increase was proportionately similar at 48 and 72 h compared with basal levels. Therefore, the effect of all inhibitors was determined on Ang II-induced wound healing after 24 h in subsequent experiments.

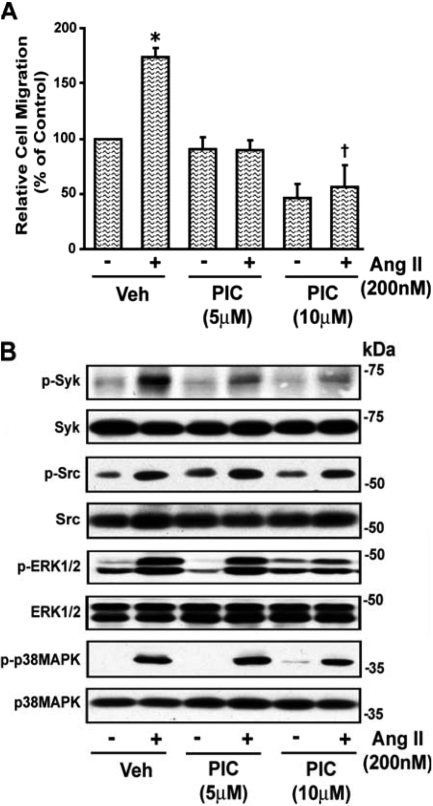

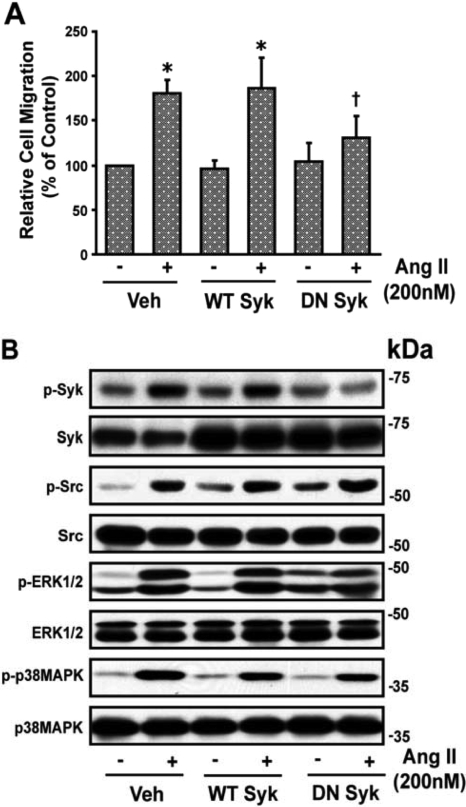

Treatment of VSMCs with the Syk inhibitor piceatannol (10 μM) significantly reduced Ang II (200 nM)-induced wound healing of VSMCs (Fig. 1A). The Ang II-induced increase in phosphorylation of Syk and ERK1/2 (2.64 ± 0.52- and 3.66 ± 0.69-fold, respectively), was inhibited by piceatannol (10 μM) (1.42 ± 0.22- and 2.88 ± 0.79-fold, respectively) (p < 0.05). However, Ang II-induced phosphorylation of c-Src and p38 MAPK (1.74 ± 0.21- and 6.32 ± 1.44-fold, respectively) was not inhibited by piceatannol (10 μM) (1.73 ± 0.11- and 5.43 ± 0.17-fold, respectively), indicating that Syk is downstream of c-Src and p38 MAPK. A representative blot is shown in Fig. 1B. To further assess the role of Syk in Ang II-induced VSMC migration, 60 to 70% confluent quiescent VSMCs were transiently transfected with WT or DN Syk mutant for 48 h using Effectene reagent, as described under Materials and Methods. Transient transfection of VSMCs with DN Syk but not WT Syk inhibited the significant increase (p < 0.05) in Ang II-induced wound healing of VSMCs (Fig. 2A) and phosphorylation of Syk from 2.67 ± 0.32-fold from basal (absence of Ang II) to 0.88 ± 0.19-fold (p < 0.05) but did not alter the significant increase in phosphorylation (p < 0.05) of c-Src, ERK1/2, or p38 MAPK (2.76 ± 0.79-, 2.52 ± 0.09-, and 5.99 ± 1.44-fold to 3.13 ± 1.67-, 2.38 ± 0.62-, and 5.04 ± 0.91-fold, respectively). A representative blot is shown in Fig. 2B.

Fig. 1.

Piceatannol inhibits Ang II-stimulated VSMC migration. A, subconfluent VSMCs were washed twice with serum-free medium 199 and wounded by scraping, and images were taken at the initial time of wounding (0 h) using a microscope followed by treatment with piceatannol (PIC) (5 and 10 μM) for 30 min. Cells were then treated with Ang II (200 nM) and after 24 h, images were again taken with the same microscope equipped with a camera and MetaMorph image analysis software. The remaining wound area was quantified, and the results are represented as relative cell migration versus control from three different batches of cells (prepared from six animals). Values are means ± S.E. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in absence of Ang II (p < 0.05). †, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in the presence of vehicle (Veh) (p < 0.05). B, quiescent VSMCs were treated with and without the Syk inhibitor piceatannol (5 and 10 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with Ang II (200 nM) for 10 min. An equal amount of protein from each treatment was analyzed by Western blotting for phospho (p)-Syk, p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho- and nonphospho-specific antibodies. The representative blots of three experiments are shown.

Fig. 2.

Transient transfection of VSMCs with DN Syk plasmid inhibits Ang II-induced VSMC migration. A, confluent VSMCs (60–80%) were transiently transfected with WT or DN Syk for 48 h and then starved overnight before treatment with Ang II. Plasmid-transfected VSMCs were washed twice with serum-free medium 199 and wounded by scraping, and images were taken at the initial time of wounding (0 h) using a microscope. Cells were then stimulated with Ang II (200 nM) and after 24 h; images were taken and quantitated as described in the legend to Fig. 1. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in presence of Ang II (p < 0.05). B, quiescent VSMCs were transiently transfected with WT or DN Syk mutant and were treated with Ang II and analyzed by Western immunoblotting for phospho (p)-Syk, p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho- and nonphospho-specific antibodies as described in legend to Fig. 1. The representative blots of three experiments are shown. Veh, vehicle.

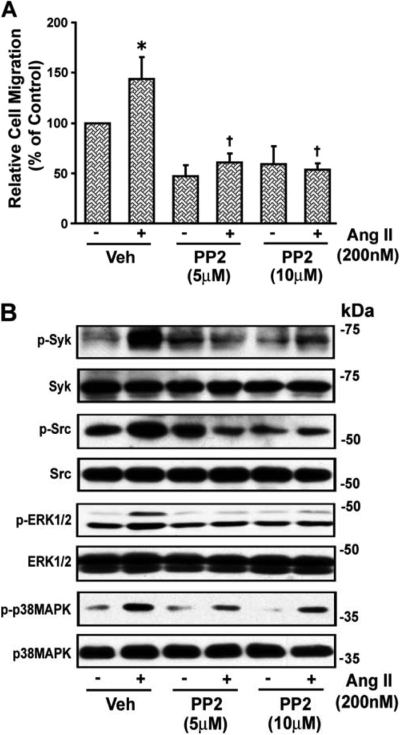

The inhibitor of the Src family of tyrosine kinases, PP2 (5 and 10 μM), reduced the basal and blocked Ang II-induced wound healing of VSMCs (Fig. 3A) and also inhibited the significant increase (p < 0.05) in phosphorylation of Syk, c-Src, and ERK1/2 from 2.5 ± 0.3-, 2.51 ± 0.52-, and 1.75 ± 0.16-fold above basal (absence of Ang II) to 1.4 ± 0.25-, 1.18 ± 0.24-, and 1.18 ± 0.1-fold, respectively (p < 0.05), but not that of p38 MAPK (4.40 ± 1.37- to 3.66 ± 0.18-fold), implying that p38 MAPK acts upstream of Src and Syk. A representative blot is shown in Fig. 3B.

Fig. 3.

Angiotensin II-induced VSMC migration is c-Src-dependent. A, confluent VSMCs grown in six-well dishes starved for 24 h and wounded, and images were taken as described above in the legend to Fig. 1. Then VSMCs were treated with the c-Src inhibitor PP2 (5 and 10 μM) for 30 min and with Ang II (200 nM) and after 24 h, images were again taken, the remaining wound area was quantitated, and results are presented as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Values are means ± S.E. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in the presence of Ang II (p < 0.05). †, values significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in the presence of vehicle (Veh) (p < 0.05). B, quiescent VSMCs were treated with and without the c-Src inhibitor PP2 (5 and 10 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with Ang II (200 nM) for 10 min. An equal amount of protein from each treatment was analyzed by Western blotting for phospho (p)-Tyr (p-EGFR), p-Syk, p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho- and nonphospho-specific antibodies. The representative blots of three experiments are shown.

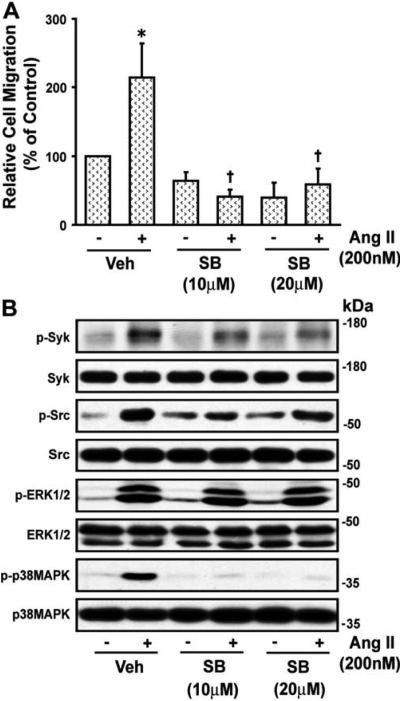

The p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 (10 and 20 μM) abolished the Ang II-induced wound healing of VSMCs (Fig. 4A) and attenuated the significant increase (p < 0.05) in phosphorylation of Syk, c-Src, and p38 MAPK from 2.43 ± 0.23-, 2.28 ± 0.42-, and 4.7 ± 0.69-fold above basal (absence of Ang II) to 1.66 ± 0.23-, 1.57 ± 0.49-, and 1.97 ± 0.64-fold, respectively (p < 0.05), indicating that Syk and c-Src participate in VSMC migration and are downstream of p38 MAPK. SB202190 did not inhibit the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 elicited by Ang II (2.89 ± 0.55- to 3.01 ± 0.29-fold). A representative blot is shown in Fig. 4B. The ERK1/2 inhibitor, U0126, blocked Ang II-induced wound healing of VSMCs but did not alter phosphorylation of Syk, c-Src, or p38 MAPK, indicating that it acts downstream of these kinases (data not shown).

Fig. 4.

Angiotensin II-induced VSMC migration is mediated by p38 MAPK. A, confluent VSMCs were wounded, and field images were taken as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Then VSMCs were treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 (SB, 10 and 20 μM) for 30 min. Cells were then exposed to Ang II (200 nM) and after 24 h, images were again taken and the wounded area was quantitated as described under Materials and Methods. Values are means ± S.E. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in presence of Ang II (p < 0.05). †, values significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in presence of vehicle (Veh) (p < 0.05). B, quiescent VSMCs were treated with and without p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 (SB, 10 and 20 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with Ang II (200 nM) for 10 min and analyzed by Western blotting for phospho (p)-Syk, p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho- and nonphospho-specific antibodies as shown in the representative blots of three experiments.

Ang II-Induced VSMC Migration Stimulated by p38 MAPK-Activated c-Src Is Also Mediated via EGFR Transactivation Independent of Syk.

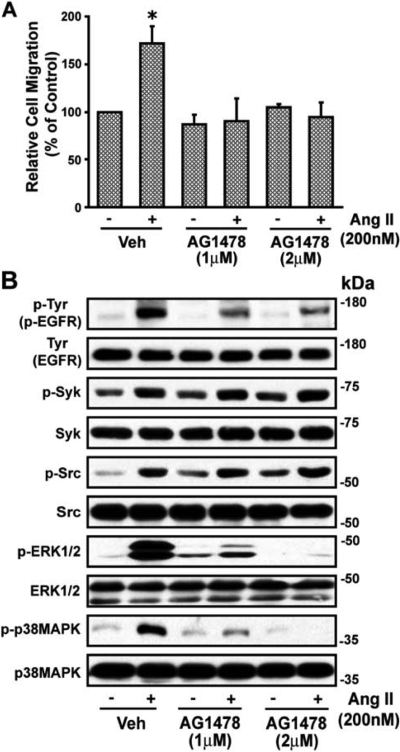

Ang II stimulates transactivation of EGFR that results in an increase in p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 activity (Eguchi et al., 1998), and EGFR activation results in VSMC migration (Saito et al., 2002). We have shown that Ang II-induced EGFR transactivation is mediated via p38 MAPK (Yaghini et al., 2007) and Ang II is known to promote association of c-Src with EGFR (Eguchi et al., 1999) and c-Src phosphorylates EGFR (Stover et al., 1995). Therefore, we determined whether p38 MAPK-activated c-Src promotes VSMC migration through EGFR by a mechanism independent of or dependent on Syk. Ang II-induced VSMC wound healing was blocked by the EGFR inhibitor, AG1478 (Fig. 5A). This agent also inhibited the Ang II-induced increases (p < 0.05) in phosphorylation of EGFR, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK from 4.94 ± 1.96-, 3.82 ± 1.0-, and 5.24 ± 1.18-fold above basal (absence of Ang II) to 2.71 ± 0.86-, 0.89 ± 0.42-, and 1.56 ± 0.42-fold, respectively (p < 0.05) but not phosphorylation of Syk or c-Src (1.82 ± 0.35-, 2.79 ± 0.75-fold to 1.78 ± 0.33-, 2.60 ± 0.30-fold, respectively). A representative blot is shown in Fig. 5B. Ang II-induced EGFR transactivation is known to cause activation of ERK1/2 and that results in VSMC migration (Eguchi et al., 2001; Saito et al., 2002; Kyaw et al., 2004). We confirmed this observation in our study. The ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 abolished Ang II-induced wound healing of VSMCs and inhibited phosphorylation of ERK1/2 but not that of Syk, EGFR, c-Src, or p38 MAPK (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Angiotensin II-induced migration of VSMCs is dependent on c-Src-induced EGFR transactivation. A, confluent VSMCs were prepared and wounded, and field images were taken as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Cells were then treated with the EGFR blocker tryphostin AG1478 (1 and 2 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with Ang II (200 nM) for 24 h, after which images were again taken and the remaining wound area was quantitated as described under Materials and Methods. Values are means ± S.E. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in the presence of Ang II (p < 0.05). B, VSMCs were treated with and without the EGFR blocker tryphostin AG1478 (1 and 2 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with Ang II (200 nM) for 10 min. Whole-cell lysates with equal amounts of protein from each treatment were analyzed by Western blotting for phospho (p)-Tyr (p-EGFR), p-Syk, p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho- and nonphospho-specific antibodies. Representative blots of three experiments are shown. Veh, vehicle.

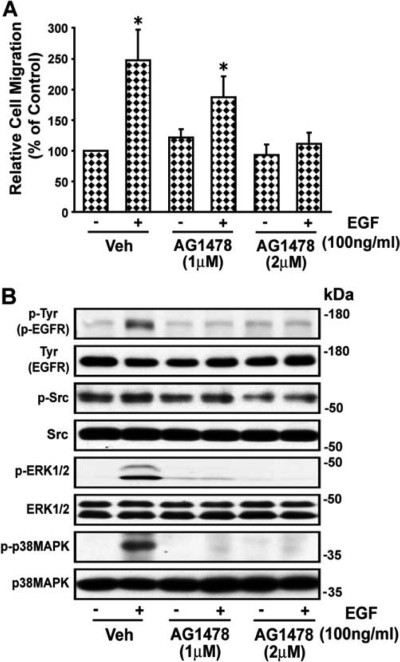

To further determine whether Ang II-induced VSMC migration is mediated by p38 MAPK-activated c-Src via Syk through EGFR transactivation, we examined the effect of the Syk inhibitor piceatannol on the action of EGF on wound healing in VSMCs. EGF caused a 2.48 ± 0.49-fold increase in wound healing of VSMCs, which was inhibited by AG1478 (Fig. 6A). EGF increased phosphorylation of EGFR, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK (2.4 ± 0.41-, 2.83 ± 0.51-, and 6.6 ± 1.82-fold above basal (absence of EGF), respectively (p < 0.05) but not of c-Src and Syk (Yaghini et al., 2007). AG1478 inhibited EGF-induced phosphorylation of EGFR, ERK1/2, and p38 MAPK to 1.35 ± 0.38-, 1.08 ± 0.09-, and 2.08 ± 0.32-fold, respectively (p < 0.05). A representative blot is shown in Fig. 6B.

Fig. 6.

EGF-induced migration of VSMCs is dependent on EGFR transactivation. A, images of the wounded confluent VSMCs were taken as described in the legend to Fig. 1, and VSMCs were treated with the EGFR blocker tryphostin AG1478 (1 and 2 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 24 h, after which images were again taken and quantitated as described under Materials and Methods. Values are means ± S.E. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in presence of EGF (p < 0.05). B, VSMCs were treated with and without the EGFR blocker tryphostin AG1478 (1 and 2 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 10 min and were analyzed by Western blotting for phospho (p)-Tyr (p-EGFR), p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho- and nonphospho-specific antibodies. Representative blots of three experiments are shown. Veh, vehicle.

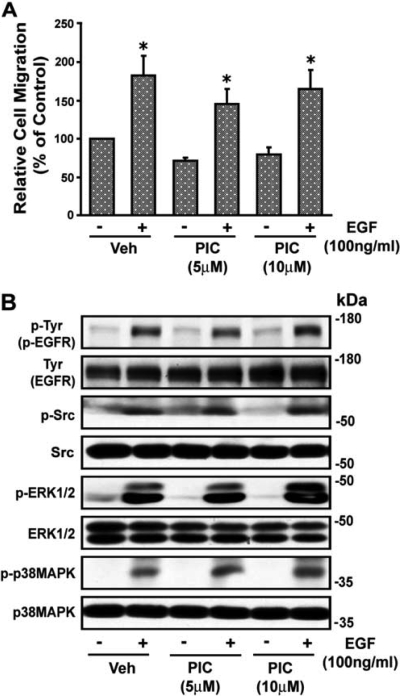

The Syk inhibitor piceatannol did not alter EGF-induced wound healing (Fig. 7A) or the increase (p < 0.05) in phosphorylation of EGFR, c-Src, ERK1/2, or p38 MAPK (from 2.15 ± 0.37-, 2.44 ± 0.56-, 4.51 ± 0.76-, and 7.08 ± 0.35-fold to 2.16 ± 0.24-, 2.27 ± 0.51-, 4.83 ± 1.32-, and 7.15 ± 2.11-fold, respectively) above basal (absence of EGF), respectively. A representative blot is shown in Fig. 7B. The DN Syk mutant also did not alter EGF-induced VSMC wound healing or EGF-induced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK or ERK1/2 (data not shown). These results indicate that VSMC migration by EGF through EGFR is mediated by p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 and is independent of c-Src and Syk.

Fig. 7.

Effect of piceatannol (PIC) on EGF-induced VSMC migration. A, images of wounded confluent VSMCs were taken as described in the legend to Fig. 1 followed by treatment with piceatannol (5 and 10 μM) for 30 min, and VSMCs were then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml). After 24 h, images were again taken and quantitated as described under Materials and Methods. Values are means ± S.E. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in presence of EGF (p < 0.05). B, quiescent VSMCs were treated with and without piceatannol (5 and 10 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 10 min, and lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis for phospho (p)-Tyr (p-EGFR), p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho- and nonphospho-specific antibodies as shown in the representative blots from three experiments. Veh, vehicle.

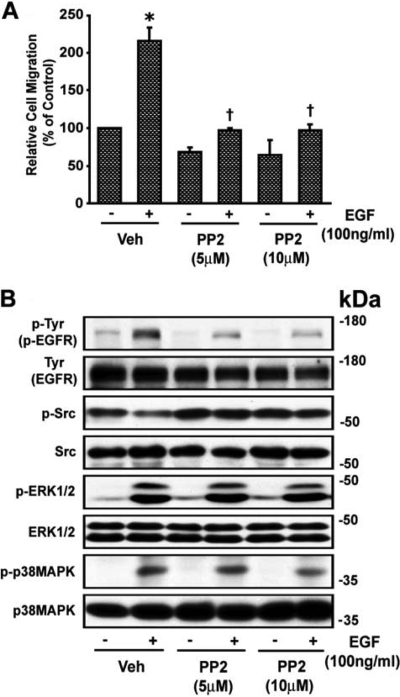

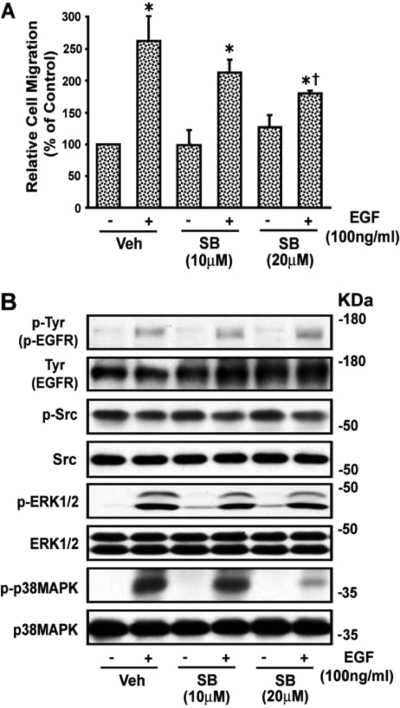

The c-Src inhibitor PP2 abolished EGF-induced wound healing of VSMCs (Fig. 8A) and phosphorylation of EGFR from 2.25 ± 0.21- to 1.27 ± 0.58-fold (p < 0.05). EGF did not increase phosphorylation of c-Src, and PP2 did not alter the EGF-induced increase in phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and ERK1/2 (3.37 ± 1.28- and 2.54 ± 0.97-fold to 3.15 ± 1.17 and 2.93 ± 1.37-fold, respectively). A representative blot is shown in Fig. 8B. The inhibitor of p38 MAPK SB202190 partially inhibited EGF-induced wound healing of VSMCs (Fig. 9A) and reduced phosphorylation of p38 MAPK from 10.35 ± 3.88-fold above basal (absence of EGF) to 5.65 ± 1.48-fold (p < 0.05) but not that of EGFR, c-Src, or ERK1/2 (1.96 ± 0.16-, 1.69 ± 0.51-, and 5.47 ± 1.53-fold to 1.81 ± 0.11-, 1.70 ± 0.47-, and 4.91 ± 1.09-fold, respectively) caused by EGF. A representative blot is shown in Fig. 9B. The ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126 blocked EGFR-induced wound healing of VSMCs and ERK1/2 phosphorylation but not that of Syk, EGFR, c-Src, or p38 MAPK (data not shown). These results indicate that p38 MAPK-activated c-Src plays a dual role in the action of Ang II to promote wound healing of VSMCs via activation of Syk as well as via EGFR transactivation through ERK1/2 and partly by p38 MAPK activation (Fig. 10).

Fig. 8.

EGF-induced VSMC migration is c-Src-dependent. A, images of wounded confluent VSMCs were taken as described in the legend to Fig. 1. VSMCs were then treated with the c-Src inhibitor PP2 (5 and 10 μM) for 30 min and with EGF (100 ng/ml) and after 24 h, images were again taken and quantitated as described under Materials and Methods. Values are means ± S.E. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in presence of EGF (p < 0.05). †, values significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in the presence of vehicle (Veh) (p < 0.05). B, VSMCs were treated with and without the c-Src inhibitor PP2 (5 and 10 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 10 min, and lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for phospho (p)-Tyr (p-EGFR), p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho- and nonphospho-specific antibodies as shown in the representative blots from three experiments.

Fig. 9.

EGF-induced VSMC migration is partially dependent on p38 MAPK. A, images of wounded confluent VSMCs were taken as indicated in the legend to Fig. 1 and treated with the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 (SB, 10 and 20 μM) for 30 min. Cells were then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) and after 24 h, images were again taken and quantitated as described under Materials and Methods. Values are means ± S.E. *, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in the presence of EGF (p < 0.05). †, value significantly different from the corresponding value obtained in presence of EGF and vehicle (Veh) of SB (p < 0.05). B, quiescent VSMCs were treated with and without SB202190 (10 and 20 μM) for 30 min and then stimulated with EGF (100 ng/ml) for 10 min, and the lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for phospho (p)-Tyr (p-EGFR), p-Src, p-ERK1/2, and p-p38 MAPK using their phospho-specific and nonphospho-specific antibodies as shown in the representative blots from three experiments.

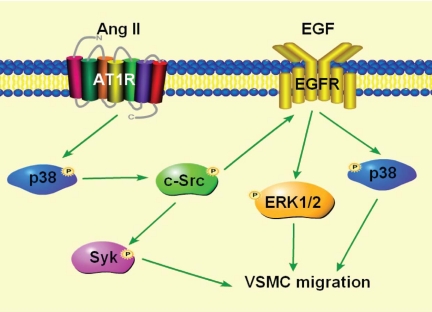

Fig. 10.

Proposed mechanism of Ang II-induced VSMC migration. Ang II-induced VSMC migration is mediated by p38-MAPK activated c-Src through two distinct but redundant pathways, one via Syk, and another via EGFR transactivation through ERK1/2 and partially through p38 MAPK.

Discussion

We have previously reported that p38 MAPK-activated c-Src promotes VSMC protein synthesis via activation of Syk and DNA synthesis via EGFR transactivation (Yaghini et al., 2007). This study was conducted to determine the contribution of Syk to Ang II-induced VSMC migration and demonstrates that Ang II promotes VSMC migration through p38 MAPK-stimulated c-Src via Syk activation as well as via EGFR transactivation through ERK1/2 and partly by p38 MAPK activation.

Contribution of Syk to Ang II-Induced VSMC Migration.

The conclusion that Syk mediates Ang II-induced VSMC migration, examined by the scratch wound method, was our demonstration that the effect of this peptide to stimulate VSMC migration was minimized by the Syk inhibitor piceatannol and in VSMCs transfected with DN Syk but not WT mutant. Because piceatannol and the DN Syk mutant, but not WT Syk, attenuated Syk phosphorylation and not that of p38 MAPK and c-Src, it appears that Syk acts downstream of p38 MAPK and c-Src in stimulating VSMC migration in response to Ang II. Piceatannol reduced Ang II-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, suggesting that ERK1/2 is activated by Syk. However, it is unlikely, because in cells transfected with the DN Syk mutant Ang II-induced Syk phosphorylation was not altered, indicating that piceatannol reduces ERK1/2 activity by a nonspecific mechanism. Ang II-induced VSMC wound healing by Syk is mediated through c-Src activation because the c-Src inhibitor PP2 blocked Ang II-induced migration of VSMCs and phosphorylation of Syk. Src family tyrosine kinases are known to associate with and activate Syk (Kurosaki et al., 1994). Because the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 blocked Ang II-induced wound healing and phosphorylation of c-Src and Syk but not of ERK1/2, it appears that p38 MAPK mediates Ang II-induced VSMC migration by c-Src-activated Syk. The mechanism by which p38 MAPK activates c-Src is not known. p38 MAPK does not appear to activate c-Src directly because 1) p38 MAPK does not associate with c-Src as determined by coimmunoprecipitation and 2) p38 MAPK immunoprecipitated from Ang II-stimulated VSMCs with phospho-p38 MAPK did not phosphorylate c-Src in an in vitro kinase assay (F. A. Yaghini and K. U. Malik, unpublished data). Whether an intermediary kinase is involved in activation of p38 MAPK by c-Src or it requires one or more scaffolding molecules for the productive interaction of p38 MAPK and c-Src remains to be determined. c-Src is known to mediate Ang II-induced VSMC migration via activation of ERK1/2 (Kyaw et al., 2004). In the present study the ERK1/2 inhibitor also blocked Ang II-induced VSMC wound healing, and the c-Src inhibitor PP2 attenuated ERK1/2 phosphorylation. However, the DN Syk mutant did not alter ERK1/2 phosphorylation, indicating that c-Src-activated ERK1/2 mediates Ang II-induced VSMC migration by a mechanism independent of Syk.

Contribution of EGFR to Ang II-Induced VSMC Migration.

Ang II is known to cause EGFR transactivation that results in activation of ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK (Eguchi et al., 1998). EGFR transactivation by Ang II is also dependent on c-Src (Eguchi et al., 1999; Touyz et al., 2002). Therefore, it is possible that c-Src might result in activation of Syk and ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK through EGFR transactivation. Our demonstration that the c-Src inhibitor PP2, but not piceatannol or the DN Syk mutant, attenuated Ang II-induced EGFR phosphorylation or EGF-induced wound healing of VSMCs and EGFR phosphorylation suggests that c-Src mediates Ang II-induced EGFR transactivation and VSMC migration independent of Syk. The EGFR blocker AG1478 attenuated EGFR phosphorylation and inhibited Ang II- and EGF-induced wound healing of VSMCs and EGF did not alter c-Src phosphorylation, suggesting that c-Src via EGFR transactivation also mediates Ang II-induced VSMC migration independent of Syk. Our finding that the p38 MAPK inhibitor SB202190 attenuated c-Src and EGFR phosphorylation suggests that p38 MAPK-activated c-Src plays a dual role in the action of Ang II to promote VSMC migration via activation of Syk as well as EGFR transactivation. The effect of Ang II to promote VSMC migration through EGFR transactivation is most likely to be mediated via ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK because the effect of Ang II as well as that of EGF to stimulate wound healing of VSMCs and ERK1/2 phosphorylation was inhibited by the ERK1/2 inhibitor U0126. The inhibitor of p38 MAPK SB202190, which blocked Ang II-induced wound healing and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK, only partially reduced EGF-induced wound healing and phosphorylation of p38 MAPK. Therefore, it seems that p38 MAPK, which activates Syk via c-Src, is more effective than p38 MAPK, which is activated through EGFR transactivation via c-Src, in stimulating VSMC migration in response to Ang II. Because the EGFR blocker AG1478 that inhibited EGF-induced p38 MAPK phosphorylation did not alter Syk phosphorylation elicited by Ang II, it seem that p38 MAPK activated by EGF is not involved in Syk phosphorylation. Four isoforms of p38 MAPK, p38α, p38β, p38γ, and p38δ, have been identified in various tissues and are differentially activated depending on the stimulus and signal strength (Conrad et al., 1999; Hale et al., 1999; Alonso et al., 2000). Therefore, it is possible that EGF activates a different isoform of p38 MAPK that is not involved in activation of Syk in response to Ang II VSMCs. Further studies on the activation of different isoforms of p38 MAPK by Ang II and EGF and their selective inhibition by their respective small interfering RNAs on Syk activation would be required to address this issue.

Our results clearly demonstrate two independent pathways for Ang II-induced migration of VSMCs mediated by p38 MAPK-activated c-Src pathways, one mediated through Syk and another through the EGF pathway. Because inhibition of each pathway blocked Ang II-induced VSMC migration, it seems that these are redundant pathways that do not appear to converge. Further studies on the transcription level could allow determining the point of convergence of these distinct pathways that lead to Ang II-induced VSMC migration.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that Ang II stimulates VSMC migration via p38 MAPK-activated c-Src through two different redundant pathways, one through activation of Syk and another via EGFR transactivation through activation of ERK1/2 and partly through p38 MAPK (Fig. 10).

Acknowledgments

We thank Anne M. Estes, Abdul Hameed Siddiqi, and Dwylette Brownlee for their excellent technical assistance, Dr. Narendra Kumar for his generous assistance in setting up the migration assay, and Dr. H. Band, Harvard Medical School (Boston, MA) for providing us with wild-type and dominant-negative Syk mutants.

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grants R01-079109 and HL094366] (to K.U.M. and C.M.W., respectively); and the National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [Grant 2T32-HL00764] (Training Grant to B.E.M.). C.K.B. was supported by the Scientific and Technical Research Council of Turkey (TUBITAK).

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://jpet.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/jpet.109.157552

- Ang II

- angiotensin II

- VSMC

- vascular smooth muscle cell

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- p38 MAPK

- p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase

- c-JNK

- c-Jun N-terminal kinase

- Pyk2

- proline-rich tyrosine kinase

- c-Src

- c-terminal nonreceptor tyrosine kinase

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- Syk

- spleen tyrosine kinase

- AG1478

- (4-(3-chloroanilino)-6,7-dimethoxyquinazoline

- SB202190

- 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole

- U0126

- 1,4-diamino-2,3-dicyano-1,4-bis(2-aminophenylthio)butadiene)

- piceatannol

- trans-3,3′-4,5′-tetrahydroxy-stilbene

- PP2

- 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d]pyrimidine

- WT

- wild type

- DN

- dominant negative.

References

- Alonso G, Ambrosino C, Jones M, Nebreda AR. (2000) Differential activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms depending on signal strength. J Biol Chem 275:40641–40648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brilla CG, Maisch B, Rupp H, Funck R, Zhou G, Weber KT. (1995) Pharmacological modulation of cardiac fibroblast function. Herz 20:127–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clempus RE, Griendling KK. (2006) Reactive oxygen species signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells. Cardiovasc Res 71:216–225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad PW, Rust RT, Han J, Millhorn DE, Beitner-Johnson D. (1999) Selective activation of p38α and p38γ by hypoxia. Role in regulation of cyclin D1 by hypoxia in PC12 cells. J Biol Chem 274:23570–23576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cavanagh EM, Ferder M, Inserra F, Ferder L. (2009) Angiotensin II, mitochondria, cytoskeletal, and extracellular matrix connections: an integrating viewpoint. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296:H550–H558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi S, Dempsey PJ, Frank GD, Motley ED, Inagami T. (2001) Activation of MAP kinases by angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Metalloprotease-dependent EGF receptor activation is required for activation of ERK and p38 MAP kinase but not JNK. J Biol Chem 276:7957–7962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi S, Iwasaki H, Inagami T, Numaguchi K, Yamakawa T, Motley ED, Owada KM, Marumo F, Hirata Y. (1999) Involvement of PYK2 in angiotensin II signaling of vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension 33:201–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eguchi S, Numaguchi K, Iwasaki H, Matsumoto T, Yamakawa T, Utsunomiya H, Motley ED, Kawakatsu H, Owada KM, Hirata Y, et al. (1998) Calcium-dependent epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation mediates the angiotensin II-induced mitogen-activated protein kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 273:8890–8896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng TC, Ying WY, Hua RJ, Ji YY, de Gasparo M. (2001) Effect of valsartan and captopril in rabbit carotid injury. Possible involvement of bradykinin in the antiproliferative action of the renin-angiotensin blockade. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst 2:19–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbons GH, Pratt RE, Dzau VJ. (1992) Vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy vs. hyperplasia. Autocrine transforming growth factor-β1 expression determines growth response to angiotensin II. J Clin Invest 90:456–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale KK, Trollinger D, Rihanek M, Manthey CL. (1999) Differential expression and activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase α, β, γ, and δ in inflammatory cell lineages. J Immunol 162:4246–4252 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources (1996) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, 7th ed.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, Commission on Life Sciences, National Research Council, Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- Kobori H, Nangaku M, Navar LG, Nishiyama A. (2007) The intrarenal renin-angiotensin system: from physiology to the pathophysiology of hypertension and kidney disease. Pharmacol Rev 59:251–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurosaki T, Takata M, Yamanashi Y, Inazu T, Taniguchi T, Yamamoto T, Yamamura H. (1994) Syk activation by the Src-family tyrosine kinase in the B cell receptor signaling. J Exp Med 179:1725–1729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kyaw M, Yoshizumi M, Tsuchiya K, Kagami S, Izawa Y, Fujita Y, Ali N, Kanematsu Y, Toida K, Ishimura K, et al. (2004) Src and Cas are essentially but differentially involved in angiotensin II-stimulated migration of vascular smooth muscle cells via extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase activation. Mol Pharmacol 65:832–841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HM, Lee CK, Lee SH, Roh HY, Bae YM, Lee KY, Lim J, Park PJ, Park TK, Lee YL, et al. (2007) p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase contributes to angiotensin II-stimulated migration of rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Pharmacol Sci 105:74–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan R, Scott S, Bai W, Yerneni KK, Nadler J. (1999) Angiotensin II signaling in vascular smooth muscle cells under high glucose conditions. Hypertension 33:378–884 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navar LG. (1997) The kidney in blood pressure regulation and development of hypertension. Med Clin North Am 81:1165–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsu H, Mifune M, Frank GD, Saito S, Inagami T, Kim-Mitsuyama S, Takuwa Y, Sasaki T, Rothstein JD, Suzuki H, et al. (2005) Signal-crosstalk between Rho/ROCK and c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase mediates migration of vascular smooth muscle cells stimulated by angiotensin II. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:1831–1836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakugi H, Wang DS, Dzau VJ, Pratt RE. (1994) Potential importance of tissue angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition in preventing neointima formation. Circulation 90:449–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rocic P, Lucchesi PA. (2001) Down-regulation by antisense oligonucleotides establishes a role for the proline-rich tyrosine kinase PYK2 in angiotensin II-induced signaling in vascular smooth muscle. J Biol Chem 276:21902–21906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoshima J, Izumo S. (1993) Molecular characterization of angiotensin II-induced hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes and hyperplasia of cardiac fibroblasts. Critical role of the AT1 receptor subtype. Circ Res 73:413–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito S, Frank GD, Motley ED, Dempsey PJ, Utsunomiya H, Inagami T, Eguchi S. (2002) Metalloprotease inhibitor blocks angiotensin II-induced migration through inhibition of epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 294:1023–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servant MJ, Giasson E, Meloche S. (1996) Inhibition of growth factor-induced protein synthesis by a selective MEK inhibitor in aortic smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 271:16047–16052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover DR, Becker M, Liebetanz J, Lydon NB. (1995) Src phosphorylation of the epidermal growth factor receptor at novel sites mediates receptor interaction with Src and P85α. J Biol Chem 270:15591–15597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki Y, Ruiz-Ortega M, Lorenzo O, Ruperez M, Esteban V, Egido J. (2003) Inflammation and angiotensin II. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 35:881–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM. (2003) The role of angiotensin II in regulating vascular structural and functional changes in hypertension. Curr Hypertens Rep 5:155–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM. (2004) Reactive oxygen species and angiotensin II signaling in vascular cells—implications in cardiovascular disease. Braz J Med Biol Res 37:1263–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM, He G, Wu XH, Park JB, Mabrouk ME, Schiffrin EL. (2001) Src is an important mediator of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2-dependent growth signaling by angiotensin II in smooth muscle cells from resistance arteries of hypertensive patients. Hypertension 38:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM, Schiffrin EL. (2000) Signal transduction mechanisms mediating the physiological and pathophysiological actions of angiotensin II in vascular smooth muscle cells. Pharmacol Rev 52:639–672 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Touyz RM, Wu XH, He G, Salomon S, Schiffrin EL. (2002) Increased angiotensin II-mediated Src signaling via epidermal growth factor receptor transactivation is associated with decreased C-terminal Src kinase activity in vascular smooth muscle cells from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 39:479–485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uddin MR, Muthalif MM, Karzoun NA, Benter IF, Malik KU. (1998) Cytochrome P-450 metabolites mediate norepinephrine-induced mitogenic signaling. Hypertension 31:242–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters CM, Savla U. (1999) Keratinocyte growth factor accelerates wound closure in airway epithelium during cyclic mechanical strain. J Cell Physiol 181:424–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber H, Taylor DS, Molloy CJ. (1994) Angiotensin II induces delayed mitogenesis and cellular proliferation in rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Correlation with the expression of specific endogenous growth factors and reversal by suramin. J Clin Invest 93:788–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss D, Sorescu D, Taylor WR. (2001) Angiotensin II and atherosclerosis. Am J Cardiol 87:25C–32C [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi XP, Graf K, Goetze S, Fleck E, Hsueh WA, Law RE. (1999) Central role of the MAPK pathway in ang II-mediated DNA synthesis and migration in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 19:73–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghini FA, Li F, Malik KU. (2007) Expression and mechanism of spleen tyrosine kinase activation by angiotensin II and its implication in protein synthesis in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biol Chem 282:16878–16890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]