Abstract

Background

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are typically thought to have a delay of several weeks in the onset of their clinical effects. However, recent reports suggest they may have a much earlier therapeutic onset. A reduction in amygdala responsivity has been implicated in the therapeutic action of SSRIs.

Aims

To investigate the effect of a single dose of an SSRI on the amygdala response to emotional faces.

Method

Twenty-six healthy volunteers were randomised to receive a single oral dose of citalopram (20 mg) or placebo. Effects on the processing of facial expressions were assessed 3 h later using functional magnetic resonance imaging.

Results

Volunteers treated with citalopram displayed a significantly reduced amygdala response to fearful facial expressions compared with placebo.

Conclusions

Such an immediate effect of an SSRI on amygdala responses to threat supports the idea that antidepressants have an earlier onset of therapeutically relevant effects than conventionally thought.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are conventionally thought to have a delay of several weeks in the onset of their clinical antidepressant effects. Recent meta-analyses suggest, however, that antidepressants may have a much earlier therapeutic onset than originally thought.1,2 This notion of early-onset antidepressant effects is supported by a series of studies in our laboratory demonstrating measurable psychological effects following acute and short-term administration of antidepressant agents to healthy volunteers.3–5 One of the most striking features of these findings is that these changes occur well before the purported onset of the therapeutic effects of antidepressants. Both depression and anxiety disorders have been associated with hyperactivity of the amygdala and converging evidence demonstrates that one mechanism by which SSRIs may exert their action is by constraining such overactivity.6–9 A recent report of decreased amygdala responses to aversive facial expressions following acute intravenous citalopram administration to healthy male volunteers intriguingly suggests that modulating amygdala reactivity may be an immediate effect of SSRI administration.10 However, interpretation of the clinical implications of this finding is problematic since intravenous SSRI administration is not typically used in the treatment of patients. The present study therefore investigated whether a single oral dose of the SSRI citalopram would have similar effects on the amygdala response to emotional faces in healthy volunteers. Given the likely role of the amygdala in the eventual therapeutic action of SSRIs, a decrease in amygdala reactivity to threat following a single dose of citalopram administered in the form and dose in which it would typically be given to patients would lend support to the notion of an early onset of therapeutically relevant antidepressant effects.

Method

Participants

Twenty-six right-handed healthy volunteers (13 women and 13 men) aged 19–30 years took part in this study. Volunteers were recruited using adverts in university departments and screened through a medical examination and a psychiatric interview using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I disorders.11 Exclusion criteria were: history of psychiatric disorder (including anxiety disorders, depression, eating disorders, psychosis and substance misuse); any significant medical condition (including migraine, diabetes, epilepsy and hypertension); pregnancy; current medication (excluding the contraceptive pill); or first-degree family history of bipolar disorder. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scanning also required the following exclusion criteria: cardiac pacemaker; mechanical heart valve; or any other mechanical implants. All participants had normal or corrected to normal vision. All participants gave their written consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the local ethics committee.

Experimental design

Participants were randomised to receive a single oral dose of citalopram (20 mg) or a matched placebo tablet. The two groups were matched in terms of gender, age, years of education, verbal IQ (assessed with the National Adult Reading Test12), trait anxiety13 and scores on the Beck Depression Inventory14 (Table 1). Participants were asked to fast for 3 h prior to attending the laboratory. On arrival, the medication was administered and scanning commenced 3 h later. Subjective state was measured at baseline and immediately prior to the fMRI scan using the Befindlichkeits scale of mood and energy,15 the State Anxiety Inventory13 and the Positive and Negative Affect Scale.16 Following the fMRI scan, volunteers completed a facial expression recognition task. Female volunteers were not tested during their pre-menstrual week.

Table 1.

Demographic details, trait anxiety and depression scores at baseline for 26 healthy volunteers randomly assigned to receive citalopram or placebo

|

Placebo

|

Citalopram

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

|

Total in group, n |

6

|

7

|

7

|

6

|

| Age, years: mean (s.d.) | 23.2 (2.6) | 23.4 (3.3) | 25.4 (3.6) | 24.5 (3.0) |

|

Verbal IQ, mean (s.d.)

|

113.5 (3.0)

|

118.4 (4.0)

|

116.4 (6.1)

|

117.7 (4.0)

|

|

Years of education, mean (s.d.)

|

16.2 (1.8)

|

17.3 (2.1)

|

16.2 (2.4)

|

18.3 (2.3)

|

|

Trait anxiety score, mean (s.d.)

|

29.8 (3.8)

|

30.7 (5.0)

|

29.4 (6.5)

|

31 (1.4)

|

|

Beck Depression Inventory score, mean (s.d.)

|

1.9 (1.1)

|

1.6 (1.9)

|

2 (1.2)

|

2.4 (2.9)

|

Stimuli and task

An fMRI block design with backwardly masked and unmasked presentations of fearful, happy and neutral facial expressions was used to assess the effect of citalopram on the neural response to implicit and explicit threatening stimuli. The facial stimuli were taken from Ekman & Friesen's Pictures of Facial Affect series.17 In the masked condition, fearful, happy and neutral faces were presented for 17 ms and immediately followed by a neutral face presented for 183 ms. In the unmasked condition, fearful, happy and neutral faces were presented in isolation for 200 ms. On each trial, participants were required to judge and report (via a button press) the gender of the face. In the masked condition, the gender of the target and the mask was always the same. The task consisted of four 20 s blocks of each of the six conditions (masked fearful, masked happy, masked neutral, unmasked fearful, unmasked happy and unmasked neutral) and there were ten faces/face-mask pairs presented per block. Between each block and at the start and end of the task, there was a 20 s baseline fixation block, where participants were simply asked to stare at a fixation point on an otherwise blank screen. Blocks were presented in a random order.

Following the faces task, a visual checkerboard task was used to control for a possible confounding effect of global drug-related modulation of the blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal, by assessing the effect of citalopram on BOLD signal in the primary visual cortex. This was a passive visual task where the participants viewed two alternating configurations of black and white squares that switched at a frequency of 8 Hz. Stimuli were presented in a block design with 15 s blocks of stimulation alternating periodically with 15 s blocks of a stationary fixation cross. In all, 20 cycles of visual stimulation/fixation were presented, lasting 5 min in total. Participants were instructed to lie quietly with their eyes open throughout the experiment.

Following the fMRI scan, volunteers were given a full facial expression recognition test, featuring examples of six emotions (fear, happiness, sadness, surprise, anger and disgust). The face stimuli were also taken from the Ekman & Friesen's series17 but there was no overlap with the stimuli used in the fMRI task. Each prototype had been averaged between full emotion and neutral in 10% steps using computer graphic techniques (see Harmer et al3 for more details). There were four examples of each emotion presented at ten different intensity levels, giving a total of 40 stimuli per emotion. Each face was also given in a neutral expression, giving a total of 250 stimuli presentations. Face stimuli were presented for 500 ms and replaced by a blank screen. Volunteers were asked to indicate which expression they thought the face depicted by pressing a labelled key on the keyboard.

Imaging data acquisition

All imaging data were collected using a Siemens Sonata scanner operating at 1.5 T, located at the Oxford Centre for Clinical Magnetic Resonance Research. For the faces task, functional imaging consisted of 24 T2*-weighted echo-planar image slices (repetition time (TR) = 3000 ms, echo time (TE) = 54 ms, 128×128 matrix), 1.5×1.5×4.5 mm voxels. For the visual stimulation paradigm, functional imaging consisted of 35 T2*-weighted echo-planar image slices (TR = 3000 ms, TE = 50 ms, 64×64 matrix), 3 mm isotropic voxels. To facilitate later co-registration of the fMRI data into standard space, we also acquired a Turbo FLASH sequence (TR = 12 ms, TE = 5.65 ms), 1 mm3 voxel size. The first two echo-planar image volumes in each session were discarded to avoid T1 equilibrium effects.

Imaging data analysis

Imaging data were preprocessed and analysed using FEAT (FMRI Expert Analysis Tool) version 5.43, part of FSL (FMRIB's Software Library, www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). The following pre-statistics processing was applied: motion correction using FMIRB's linear image registration tool (MCFLIRT);18 non-brain removal using the Brain Extraction Tool;19 spatial smoothing using a Gaussian kernel of full width half maximum 5 mm; mean-based intensity normalisation of all volumes by the same factor; highpass temporal filtering (Gaussian-weighted least-squares straight line fitting, with sigma = 50.0 s). Registration to high resolution images and to a standard template (Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) 152 stereotactic template) was carried out using FLIRT.18,20

Six experimental conditions were modelled: maskedunmasked fear, masked/unmasked happy and masked/unmasked neutral. Each condition was modelled separately by convolving trials with a canonical haemodynamic response function. Temporal derivatives were included as covariates of no interest to increase statistical sensitivity. All analyses were performed at the group level using mixed-effects analyses.21,22 Z (Gaussianised T) statistical images were thresholded using clusters determined by Z>2.3 and a (corrected) cluster significance threshold of P = 0.05.23 Foci of activation were localised with the aid of the Talairach atlas tool in FSL View, which is a digitised conversion of the original Talairach atlas,24 in which a correcting affine transformation has been applied to register it into MNI 152 space.25

For the faces task, the neural responses in the control blocks were subtracted from those in the active blocks in the placebo group to reveal the main effect of the task. The active minus control comparisons were: masked fearful facial expression minus masked neutral facial expression; unmasked fearful facial expression minus unmasked neutral facial expression; masked happy facial expression minus masked neutral facial expression; unmasked happy facial expression minus unmasked neutral facial expression. For those regions with a significant main effect of task, the percentage BOLD signal change for each contrast was calculated in order to identify the profile of drug effect. This analysis method of assessing differences in activation patterns between the drug and placebo groups within a task-specific context has been used in previous pharmacological fMRI studies in healthy volunteers (e.g. Del-Ben et al10).

For the visual checkerboard task, a region of occipital cortex activated by the task (compared with baseline) was identified. The percentage BOLD signal change was extracted for this region and compared between the citalopram and placebo groups using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with drug group as the between-participants factor (two levels: citalopram, placebo). Any effect of citalopram in this region would suggest a global drug effect on baseline cerebral haemodynamics or neural coupling.

Two participants' data (both in the placebo group) were excluded from the fMRI analysis. In one participant there was a fault in the high resolution structural image and in the other, a cerebellar cyst was identified on the structural scan. Thus, the fMRI analysis included 24 participants (13 citalopram, 11 placebo).

Subjective ratings and behavioural data were analysed using a repeated measures ANOVA model. Significant interactions were further corroborated using independent sample t-tests.

Results

Subjective ratings

A single oral dose of citalopram in healthy volunteers did not significantly affect ratings of mood, anxiety or energy on the subjective rating scales used (all comparisons with placebo P>0.15).

Imaging data

Main effect of task

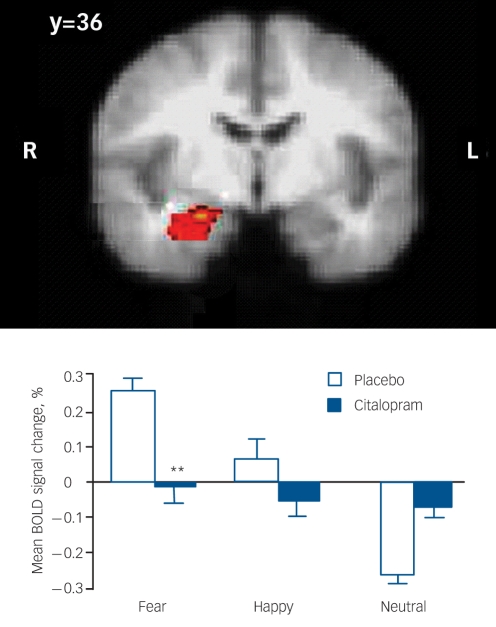

The main effect of task in the placebo group revealed significantly greater responses to the unmasked fear stimuli compared with the unmasked neutral stimuli in the right amygdala (peak cluster activation MNI coordinates: x = 22, y = –6, z = –18; Fig. 1) and the medial frontal gyrus (peak cluster activation MNI coordinates: x =0, y = 36, z = –22). There were no main effects of task in the placebo group for the unmasked happy v. unmasked neutral contrast, or for the masked fear v. masked neutral and masked happy v. masked neutral contrasts.

Fig. 1.

Increased right amygdala activation in the placebo group associated with the contrast between unmasked fear and unmasked neutral faces and plot of mean percentage blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signal change in this right amygdala cluster after acute oral treatment with citalopram and placebo. Image is thresholded at Z = 2.3, P = 0.05, corrected. Bars show the mean; error bars show the standard error of the mean. Asterisks represent significant level of difference from placebo (**P<0.01).

Effect of citalopram administration

In order to examine the effect of citalopram on the neural response to fearful v. neutral facial expressions, we extracted the percentage BOLD signal change for the two clusters identified in the main effect of task analysis and compared the citalopram and placebo groups. In the right amygdala cluster, there was a significant interaction between drug group and facial expression (F(2,44) = 11.867, P = 0.001) in the unmasked condition. This group × expression interaction was further corroborated by independent sample t-tests of each facial expression, which revealed significantly decreased activation in the citalopram group to fearful facial expressions (t(22) = –3.467, P = 0.002) but no significant differences between groups to happy or neutral facial expressions in this region (Fig. 1). There was no significant main effect of drug group and no significant interaction with facial expression in the medial frontal gyrus cluster for the unmasked condition and in either region for the masked condition.

Visual stimulation paradigm

In the checkerboard task, visual stimulation was associated with a large and highly significant activation cluster in the occipital cortex. There were no significant effects of drug group on percentage BOLD signal change in this region of occipital cortex during visual stimulation (F(1,23) = 0.651, P = 0.4), suggesting that the observed effects during face processing did not reflect global haemodynamic changes.

Behavioural measures

To assess how the modification of neural responses by citalopram may relate to behavioural responses, we assessed facial expression recognition after the fMRI scan using a second set of facial expressions. There was a significant interaction between treatment group and facial expression in accuracy of facial expression recognition (F(6,144) = 2.265, P = 0.04). This was further corroborated using independent sample t-tests for each expression (Table 2), which revealed that recognition of happy expressions was significantly increased in the citalopram group compared with the placebo group (t(24) = 2.057, P = 0.05). The recognition of disgust was conversely marginally decreased in the citalopram group compared with the placebo group (t(24) = –2.008, P = 0.06). There was no significant main effect of treatment group or significant treatment group × facial expression interaction on reaction times in this task (all P>0.3). This pattern of effects remains the same if the data from the two participants that were not included in the fMRI data analysis are excluded.

Table 2.

Accuracy of facial expression recognition following citalopram or placebo assessed after the functional magnetic resonance imaging scana

| Expression | Citalopram (n = 13) Mean (s.e.) | Placebo (n = 13) Mean (s.e.) | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anger | 21.2 (1.2) | 18.6 (1.03) | t(24) = 1.6, P = 0.12 |

|

Disgust

|

13.7 (1.6)

|

18.2 (1.5)

|

t(24) = –2.0, P = 0.06

|

|

Fear

|

19.2 (1.1)

|

17.5 (1.2)

|

t(24) = 0.99, P = 0.33

|

|

Happiness

|

25.8 (0.4)

|

24 (0.8)

|

t(24) = 2.06, P = 0.05

|

|

Sadness

|

18.4 (1.6)

|

17.4 (1.6)

|

t(24) = 0.45, P = 0.904

|

|

Surprise

|

21 (1.6)

|

22 (0.9)

|

t(24) = –0.54, P = 0.66

|

|

Neutral

|

7.6 (0.4)

|

7.5 (0.5)

|

t(24) = 0.12, P = 0.59

|

Recognition accuracy for happy facial expressions was significantly increased in the citalopram group compared with the placebo group

Discussion

Our results demonstrate an immediate effect of a clinical oral dose of an SSRI on the amygdala response to threat. Despite the lack of subjective mood effects, participants treated with a single dose of citalopram displayed a significantly reduced amygdala response to fearful facial expressions compared with placebo. Such a finding lends support to the notion that antidepressants may have an earlier onset of therapeutically relevant action than conventionally thought.

Effect of citalopram on amygdala function

The processing of emotional stimuli is known to be aberrant in mood disorders such as depression and anxiety, with increased negative and threat-relevant processing. For example, patients vulnerable to depression show increased recognition of fearful facial expressions26 and heightened anxiety has been shown to be associated with increased attentional orienting to threat-related stimuli.27 The amygdala is known to be involved in the processing of emotional stimuli and in particular the rapid detection of threat-relevant cues such as fearful facial expressions.28 Consistent with these cognitive effects, neuroimaging studies of depression and anxiety disorders have reported hyperactivity in the amygdala both at rest29 and in response to presentations of emotional facial expressions.30,31

The current study is consistent with a body of evidence that suggests that a key action of antidepressant drugs involves constraining such overactivity in the amygdala. In line with this, preclinical studies have shown that serotonin has an inhibitory effect on amygdala function.32 Clinical studies have also demonstrated that effective antidepressant treatment is associated with decreased resting amygdala metabolism33 and decreased amygdala response to emotionally valenced material.7,8 Further support for a central role of the amygdala in antidepressant action comes from studies of healthy volunteers, which allow the direct action of the antidepressant to be examined unconfounded by symptom remission or mood change. To date, two such studies have shown a decrease in amygdala responsivity to aversive facial expressions following 7 days of treatment with citalopram9 and acute intravenous citalopram,10 suggesting that the effects on the amygdala may represent a direct action of the SSRI. Our finding of decreased amygdala reactivity to fearful facial expressions following a single oral dose of citalopram extends and strengthens this idea.

Acute effects of SSRIs

Paradoxically, the acute behavioural effects of serotonergic antidepressants can be opposite to those seen following chronic treatment. In particular, anxiety symptoms are often exacerbated early in SSRI treatment, before the therapeutic effects emerge.34 A reversal of action from acute to repeated administration of SSRIs has been demonstrated in animal models of anxiety, with an increase in auditory fear conditioning following acute administration of citalopram and a decrease following repeated (21 day) administration.35 Similarly in healthy human volunteers, acute administration of citalopram increases the recognition of fearful facial expressions and the emotion-potentiated startle,4,5 whereas repeated administration is associated with decreases on both of these measures.3

Given that fear conditioning, the processing of threatening facial expressions and the emotion-potentiated startle response have all been shown to critically involve the amygdala, it has been previously hypothesised that increased activity in this structure might underpin the acute anxiogenic effects of SSRIs.5,35 However, the present study and the one previous study reporting reduced amygdala activation following acute citalopram10 do not support this notion, suggesting that the amygdala may not be the locus of the acute anxiogenic effects of SSRIs.

It is important to note, however, that these adverse acute effects of SSRIs only affect a subset of patients clinically and the effects of acute manipulations of serotonin have been shown to be dependent on a number of factors such as gender36 and genotype.37 This raises the possibility that the amygdala may be involved in the acute anxiogenic effects of SSRIs but that the sample used in the current study were not susceptible to such an anxiogenic effect. Consistent with this hypothesis, the citalopram group showed the expected increase in the recognition of happy facial expressions on the behavioural facial expression recognition task but, unlike participants in a number of previous studies of acute serotonergic manipulation,4,5,36 they did not show an increase in the recognition of fearful facial expressions. Although this may be due to the reduced sensitivity of this measure as a result of habituation effects resulting from repeated exposure to fearful faces during the fMRI scan, the involvement of the amygdala in the acute anxiogenic effect of SSRIs remains unresolved. Future studies are needed to examine the reactivity of the amygdala to threatening stimuli in those individuals who demonstrate a measurable behavioural increase in fear processing in response to acute SSRI treatment.

Amygdala response to masked emotional faces

Repeated administration of citalopram to healthy volunteers has previously been shown to reduce the amygdala response to fearful faces when they are presented in a backwardly masked paradigm.9 In contrast, in the present study there was no significant effect of acute citalopram on the amygdala response to masked fearful or happy faces. However, caution must be exercised in the interpretation of this lack of drug effect in the masked condition. In the placebo group, the amygdala response was not increased to masked fearful relative to neutral or happy facial expressions, which is inconsistent with some38 but not all39 previous findings. The amygdala response to masked fearful facial expressions appears to be a variable effect which is sensitive to individual variation in factors such as state anxiety40 and also the processing load of the task.41 In the absence of the basic main effect of the task, it is not possible to draw conclusions about the effect of acute citalopram on non-conscious processing of threat.

Pharmacological fMRI

The use of BOLD fMRI to investigate the pharmacological modulation of brain activity by psychoactive drugs is a growing area of research.42 However, in such studies it must be considered whether pharmacological modulations of the BOLD signal reflect global influences on neurovascular coupling, rather than specific modulations of neural activity. For example, changes in the BOLD signal following drug administration could reflect influences of the drug not only on neural activity, but also on the synaptic and metabolic signalling to the blood vessels that control the cerebral blood flow responses, as well as the reactivity of the cerebral vasculature. One method that is often used to control for such non-specific global modulations of signalling or vasculature reactivity by the drug is the inclusion of a control task to assess the BOLD response in a region that is not expected to be modulated by the drug, such as the visual stimulation paradigm used in this study. Using this paradigm, it was found that citalopram has no significant effect on the BOLD signal change in the occipital region activated by this task, which suggests that global vascular effects of the drug cannot account for the presence of citalopram-mediated modulations of the BOLD response to threat-related stimuli. However, it is important to note that such a control task does not preclude the possibility of non-specific effects that are restricted to the regions that are engaged by the main task of interest.43 Future studies employing perfusion methodologies for comparison of absolute values of blood flow during baseline conditions are needed to address this issue further.

Summary

The present study demonstrates that SSRIs have immediate and discernable effects on neural circuitry that appear to be important in their eventual therapeutic action. This mirrors previous behavioural findings that demonstrate measurable psychological changes following a single dose of an antidepressant5 and suggests that altered processing of emotionally valenced stimuli may represent an important mechanism through which antidepressants eventually exert their clinical effects on subjective mood. It is possible that the rapid reduction in amygdala activity by antidepressant drugs is an important mechanism for subsequent clinical antidepressant effects.

Funding

This research was funded by a Wellcome Trust studentship.

Declaration of interest

None.

References

- 1.Taylor MJ, Freemantle N, Geddes JR, Bhagwagar Z. Early onset of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant action: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63: 1217-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Posternak MA, Zimmerman M. Is there a delay in the antidepressant effect? A meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 2005; 66: 148-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harmer CJ, Shelley NC, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM. Increased positive versus negative affective perception and memory in healthy volunteers following selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibition. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 1256-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Browning M, Reid C, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM, Harmer C. A single dose of citalopram increases fear recognition in healthy subjects. J Psychopharmacol 2007; 21: 684-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harmer CJ, Bhagwagar Z, Perrett DI, Vollm BA, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM. Acute SSRI administration affects the processing of social cues in healthy volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003; 28: 148-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Drevets WC. Neuroimaging abnormalities in the amygdala in mood disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003; 985: 420-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheline YI, Barch DM, Donnelly JM, Ollinger JM, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA. Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biol Psychiatry 2001; 50: 651-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu CH, Williams SC, Cleare AJ, Brammer MJ, Walsh ND, Kim J, et al. Attenuation of the neural response to sad faces in major depression by antidepressant treatment: a prospective, event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004; 61: 877-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harmer CJ, Mackay CE, Reid CB, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM. Antidepressant drug treatment modifies the neural processing of nonconscious threat cues. Biol Psychiatry 2006; 59: 816-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Del-Ben CM, Deakin JF, McKie S, Delvai NA, Williams SR, Elliott R, et al. The effect of citalopram pretreatment on neuronal responses to neuropsychological tasks in normal volunteers: an FMRI study. Neuropsychopharmacology 2005; 30: 1724-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders (SCID–I). American Psychiatric Press, 1997.

- 12.Nelson HE, Willison J. National Adult Reading Test (NART). nferNelson, 1991.

- 13.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RD. Manual for the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983.

- 14.Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1961; 4: 561-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Zerssen D, Strian F, Schwarz D. Evaluation of depressive states, especially in longitudinal studies. Mod Probl Pharmacopsychiatry 1974; 7: 189-202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988; 54: 1063-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ekman P, Friesen, WV. Pictures of Facial Affect. Consulting Psychologists Press, 1976.

- 18.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 2002; 17: 825-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp 2002; 17: 143-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jenkinson M Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal 2001; 5: 143-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beckmann CF, Jenkinson M, Smith SM. General multilevel linear modeling for group analysis in FMRI. Neuroimage 2003; 20: 1052-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Woolrich MW, Behrens TE, Beckmann CF, Jenkinson M, Smith SM. Multilevel linear modelling for FMRI group analysis using Bayesian inference. Neuroimage 2004; 21: 1732-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Worsley KJ, Evans AC, Marrett S, Neelin P. A three-dimensional statistical analysis for CBF activation studies in human brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1992; 12: 900-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talairach J, Tournoux P. Co-Planar Stereotactic Atlas of the Human Brain. Thieme, 1988.

- 25.Lancaster JL, Woldroff MG, Parsons LM, Liotti M, Freitas CS, Rainey L, et al. Automated Talairach atlas labels for function brain mapping. Hum Brain Mapp 2000; 10: 120-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bhagwagar Z, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM, Harmer CJ. Normalization of enhanced fear recognition by acute SSRI treatment in subjects with a previous history of depression. Am J Psychiatry 2004; 161: 166-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mogg K, Bradley BP. A cognitive-motivational analysis of anxiety. Behav Res Ther 1998; 36: 809-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morris JS, Frith CD, Perrett DI, Rowland D, Young AW, Calder AJ, et al. A differential neural response in the human amygdala to fearful and happy facial expressions. Nature 1996; 383: 812-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drevets WC, Videen TO, Price JL, Preskorn SH, Carmichael ST, Raichle ME. A functional anatomical study of unipolar depression. J Neurosci 1992; 12: 3628-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rauch SL, Shin LM, Wright CI. Neuroimaging studies of amygdala function in anxiety disorders. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003; 985: 389-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Davidson RJ, Irwin W, Anderle MJ, Kalin NH. The neural substrates of affective processing in depressed patients treated with venlafaxine. Am J Psychiatry 2003; 160: 64-75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stutzmann GE, LeDoux JE. GABAergic antagonists block the inhibitory effects of serotonin in the lateral amygdala: a mechanism for modulation of sensory inputs related to fear conditioning. J Neurosci 1999; 19: RC8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drevets WC, Bogers W, Raichle ME. Functional anatomical correlates of antidepressant drug treatment assessed using PET measures of regional glucose metabolism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2002; 12: 527-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kent JM, Coplan JD, Gorman JM. Clinical utility of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in the spectrum of anxiety. Biol Psychiatry 1998; 44: 812-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burghardt NS, Sullivan GM, McEwen BS, Gorman JM, LeDoux JE. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor citalopram increases fear after acute treatment but reduces fear with chronic treatment: a comparison with tianeptine. Biol Psychiatry 2004; 55: 1171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Attenburrow MJ, Williams C, Odontiadis J, Reed A, Powell J, Cowen PJ, et al. Acute administration of nutritionally sourced tryptophan increases fear recognition. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003; 169: 104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neumeister A, Hu XZ, Luckenbaugh DA, Schwarz M, Nugent AC, Bonne O, et al. Differential effects of 5-HTTLPR genotypes on the behavioral and neural responses to tryptophan depletion in patients with major depression and controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2006; 63: 978-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whalen PJ, Rauch SL, Etcoff NL, McInerney SC, Lee MB, Jenike MA. Masked presentations of emotional facial expressions modulate amygdala activity without explicit knowledge. J Neurosci 1998; 18: 411-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phillips ML, Williams LM, Heining M, Herba CM, Russell T, Andrew C, et al. Differential neural responses to overt and covert presentations of facial expressions of fear and disgust. Neuroimage 2004; 21: 1484-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bishop SJ, Duncan J, Lawrence AD. State anxiety modulation of the amygdala response to unattended threat-related stimuli. J Neurosci 2004; 24: 10364-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pessoa L, McKenna M, Gutierrez E, Ungerleider LG. Neural processing of emotional faces requires attention. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002; 99: 11458-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wise RG, Tracey I. The role of fMRI in drug discovery. J Magn ResonImaging 2006; 23: 862-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iannetti GD, Wise RG. BOLD functional MRI in disease and pharmacological studies: room for improvement? Magn Reson Imaging 2007; 25: 978-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]