Abstract

We previously identified two small molecules targeting the HIV-1 gp41, N-(4-carboxy-3-hydroxy)phenyl-2,5-dimethylpyrrole 12 (NB-2) and N-(3-carboxy-4-chloro) phenylpyrrole 13 (NB-64) that inhibit HIV-1 infection at low μM level. Based on molecular docking analysis, we designed a series of 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans. Compared with 12 and 13, these compounds have bigger molecular size (437–515 Da) and could occupy more space in the deep hydrophobic pocket on the gp41 NHR-trimer. Fifteen 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans (11a–o) were synthesized by Suzuki-Miyaura cross coupling, followed by a Knoevenagel condensation and tested for their anti-HIV-1activity and cytotoxicity on MT-2 cells. We found that all 15 compounds had improved anti-HIV-1 activity and 3 of them (11a, 11b, and 11d) exhibited inhibitory activity against replication of HIV-1 IIIB and 94UG103 at <100 nM range, more than 20-fold more potent than 12 and 13, suggesting that these compounds can serve as leads for development of novel small molecule HIV fusion inhibitors.

Introduction

So far, over 60 million people have been infected with HIV and of these more than 25 million have died of AIDS.1,2 As of March of 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has licensed 28 anti-HIV drugs, including 15 reverse transcriptase inhibitors (RTI) and 10 protease inhibitors (PI) (http://www.hivandhepatitis.com/hiv_and_aids/hiv_treat.html). Application of these antiretroviral drugs in combination, designated as highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), has led to significant reduction of mobility and mortality of HIV/AIDS.3 However, an increasing number of HIV/AIDS patients fail to respond to current antiretroviral therapeutics because of the emergence of multidrug resistance to RTIs and PIs and serious adverse side effects.4–6 Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel anti-HIV therapeutics targeting different steps of HIV replication cycle, particularly the HIV fusion and entry events.

HIV type 1 (HIV-1) entry into the host cell is initiated by binding of its envelope glycoprotein (Env) surface subunit gp120 to the CD4 molecule and a coreceptor, CCR5 or CXCR4, causing a series of conformational changes of the Env transmembrane subunit gp41.7 The fusion peptide located at the N-terminus of gp41 inserts into the target cell membrane, followed by association between the N- and C-terminal heptad repeats (NHR and CHR, respectively) to form a six-helix bundle core structure, bringing the viral envelope and target cell membrane into close proximity.8,9 Peptides derived from the gp41 CHR region can interact with the viral gp41 NHR region and block fusogenic core formation, resulting in potent inhibition of HIV-1 fusion with the target cells.10–14 One of the CHR-peptides, Enfuvirtide (T-20) was licensed by the US FDA as the first member of a new class of anti-HIV drugs – HIV fusion inhibitors for treating HIV/AIDS patients who have failed to respond to RTI and PI.15,16 However, clinical application of the Enfuvirtide is limited due to its lack of oral availability, induction of drug-resistance and high cost of production.9 Therefore, it is critical to develop orally available non-peptide small-molecule fusion inhibitors.

Using a fluorescence-linked immunoabsorbance assay with a conformation-specific monoclonal antibody (mAb) NC-1,17 we previously identified two small molecules, N-(4-carboxy-3-hydroxy)phenyl-2,5-dimethylpyrrole 12 (NB-2) and N-(3-carboxy-4-chloro)phenyl-pyrrole 13 (NB-64), which inhibit HIV-1 fusion and gp41 six-helix bundle formation at low μM levels (Fig. 1).18 Molecular docking analysis of these two compounds indicates that 12 and 13 each occupies only a part of the deep hydrophobic pocket on the gp41 NHR-trimer.18 We therefore reasoned that new lead compounds with improved anti-HIV-1 potency could be designed by increasing the molecular size so that they would occupy more space in the hydrophobic pocket. We now report the design and synthesis of 15 derivatives of 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furan (11a–o) with molecular weight ranging from 437 to 515 Daltons. We evaluated their antiviral activity against HIV-1IIIB and their cytotoxicity on MT-2 cells that were used in the viral infection assay. Strikingly, all 15 compounds exhibited improved anti-HIV-1 activity and 3 of them (11a, 11b, and 11d) inhibited replication by laboratory-adapted and primary HIV-1 strains with EC50 (effective concentration for 50% inhibition) ranging from 44 to 99 nM and SI (selectivity index) in the range of 330–440. These results suggest that 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans show great potential for further development as novel small molecule anti-HIV therapeutics targeting gp41.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structures of 12 and 13.

Results and Discussion

A total of fifteen 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans (11a–o) were synthesized by Suzuki-Miyaura cross coupling, followed by a Knoevenagel condensation. Their molecular weight ranged from 436 to 515 Daltons.

We tested the inhibitory activity of these compounds on the replication of the laboratory-adapted HIV-1 strain IIIB, a prototype of the X4 strain, in MT-2 cells that express CD4 and the coreceptor CXCR4 by measuring p24 production in an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) as previously described.18 All 15 compounds significantly inhibited HIV-1 replication in a dose-dependent manner with the EC50 (effective concentration for 50% inhibition) ranging from 0.042 to 1.3 μM. We also tested the cytotoxicity of these compounds on MT-2 cells using an XTT {sodium 3′-[1- (phenylamino)-carbonyl]-3,4-tetrazolium-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro)bezenesulfonic acid hydrate} assay,19 the CC50 (concentration causing 50% cytotoxicity) values ranged from 3.29 to 78.29 μM and their selectivity index (SI) ranged from 10 to 915 (Table 3 and Fig. S1). The best compound is 11l which has the lowest EC50 (42 nM) and highest SI (915) and the worst compound is 11f, with an EC50 (1.28 μM) and SI (12). Although the compound 11i had an appreciable potency (EC50 = 0.32 μM), it had high cytotoxicity (CC50 = 3.29 μM), resulting in a SI of 10.

Table 3.

Anti-HIV-1 activity and selectivity indexes of the 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-ylidenemethyl)furans 11a–oa

| Product | MW | EC50 (μM) |

CC50 (μM) | SIb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1IIIBc | HIV-1IIIBd | 94UG103e | ||||

| 11a | 435.5 | 0.044 ± 0.005 | 0.098±0.033 | 0.074±0.015 | 19.35 ± 0.75 | 440 |

| 11b | 449.5 | 0.099 ± 0.010 | 0.031±0.016 | 0.070±0.012 | 42.14 ± 1.61 | 426 |

| 11c | 463.6 | 0.081 ± 0.011 | 0.030±0.032 | 0.177±0.061 | 17.39 ± 0.90 | 215 |

| 11d | 470.0 | 0.051 ± 0.013 | 0.017±0.003 | 0.073±0.063 | 16.82 ± 1.03 | 330 |

| 11e | 453.5 | 0.071 ± 0.010 | 0.291±0.241 | 0.246±0.037 | 27.01 ± 1.48 | 380 |

| 11f | 451.5 | 1.280 ± 0.240 | 0.261±0.098 | 2.660±0.610 | 14.78 ± 1.99 | 12 |

| 11g | 465.6 | 1.300 ± 0.151 | 0.266±0.033 | 2.229±0.176 | 28.72 ± 1.70 | 22 |

| 11h | 436.5 | 0.043 ± 0.008 | 0.092±0.004 | 0.648±0.108 | 26.84 ± 3.73 | 624 |

| 11i | 514.4 | 0.317 ± 0.071 | 0.158±0.046 | 0.165±0.019 | 3.29 ± 1.05 | 10 |

| 11j | 470.0 | 0.064 ± 0.005 | 0.078±0.017 | 0.033±0.010 | 6.73 ± 0.56 | 105 |

| 11k | 453.5 | 0.094 ± 0.002 | 0.059±0.014 | 0.801±0.138 | 78.29 ± 0.57 | 835 |

| 11l | 449.6 | 0.042 ± 0.019 | 0.071±0.004 | 0.442±0.039 | 38.43 ± 2.22 | 915 |

| 11m | 471.0 | 0.232 ± 0.020 | 1.010±0.310 | 0.598±0.155 | 38.37 ± 2.71 | 165 |

| 11n | 515.4 | 0.268 ± 0.055 | 0.227±0.080 | 0.353±0.009 | 5.53 ± 0.08 | 40 |

| 11o | 450.5 | 0.390 ± 0.070 | 0.538±0.045 | 4.043±0.079 | 78.92 ± 4.66 | 202 |

Each compound was tested in triplicate; the data were presented as the mean ± SD.

SI was calculated based on the CC50 for MT-2 cells and EC50 for inhibiting infection of HIV-1IIIB.

The experiment was performed without exclusion of light.

The experiment was performed with exclusion of light.

94UG103 is a primary HIV-1 isolate (X4R5, clade A).

Four possible isomers need to be considered for compounds 11a–o: A, B, C and D (Fig. 2). The interconvertions A↔B and C↔D should be easy as they proceed by rotation about single bonds. The interconversions of A↔C and B↔D will be more difficult because they need rotation about double bonds. We also expect that isomers A and B will be more stable than C and D because of the cross space interactions. To examine the possible intervention of the unstable product isomers C and D, we tested the anti-HIV-1 IIIB activity of these compounds under exclusion of light. As shown in Table 3, there was no substantial difference in antiviral activity of the compounds tested under dark and light conditions. This excludes the possibility that light-activation to give isomers C and D is the origin for their bioactivity.

Fig. 2.

The possible E–Z isomers of compounds 11a–o.

We also tested the inhibitory activity of these compounds on the replication of a representative primary HIV-1 isolate 94UG103 (R5X4, clade A) in PBMCs. All 15 compounds effectively inhibited HIV-1 94UG103 replication similarly in a dose-dependent manner with the EC50 ranging from 0.07 to 4 μM (Table 3 and Fig. S1). The best compounds are 11a, 11b, and 11d which have the lowest EC50 (70 – 74 nM). This result suggests that these compounds are much more potent than 12 and 13 in inhibiting infection by primary HIV-1.18 Molecular docking analysis revealed that the phenethyl group of compound 11d filled the space in the deep hydrophobic pocket of gp41 formed by the NHR trimer (Fig. 3), previously observed to be unoccupied by 13.

Fig. 3.

Docking of 11d in the gp41 hydrophobic cavity. (A) The stereo view of 11d docked in the hydrophobic cavity showing possible interactions with the neighboring hydrophobic and charged residue K574. (B) Surface representation of the gp41 core with bound ligand 11d. The compound docked inside the cavity. The negatively charged COOH group is pointing towards the positively charged area contributed by K574.

This may explain why 11d has ~25-fold greater potency than 13. In the current series we kept the phenethyl group fixed and substituted the phenyl ring attached to the furan ring to derive a comprehensive structure-activity relationship (SAR). We showed previously that the carboxylic acid group in this phenyl ring is essential for anti-HIV-1activity and hence it was retained throughout. It appears that the compound 11a with no substituent at 2 and 6 position of phenyl ring showed highly potent activity with reasonably good selectivity index. Addition of hydrophobic substituent at R (11b–d) had moderate effects and reduced the anti-HIV-1 activity by ~2–4-fold. However, bromine substitution (11i) had more severe effect probably due to steric effects and the activity dropped by ~7-fold. The most marked adverse effect on activity was demonstrated by electron donating substituents OH and OCH3, where the anti-HIV-1 activity dropped by ~30-fold. Introduction of a nitrogen atom in the ring in the unsubstituted 11a yielded the most active inhibitor (11l; EC50= 42 nm) but, when chlorine or bromine was substituted at the R position (11m and 11n) or a methyl group was introduced at R′ position (11o) a substantial decrease in activity was observed. Interestingly moving the methyl group of 11b to the R′ position yielded 11h, which was more active than 11b. However, similar moves for chlorine and fluorine had marginal effects. This SAR analysis will help us in further modifying the most active analogs obtained from the current study.

In the next stage, we will further evaluate the inhibitory activities of these 15 compounds on the HIV-1-mediated cell-cell fusion and cytopathic effect as well as the gp41 six-helix bundle formation. These data in combination with anti-HIV-1 activity and cytotoxicity well refine the structure-activity relationship, which will be used to design new, small molecule HIV-1 fusion inhibitors with improved anti-HIV-1 potency and reduced cytotoxicity for further pre-clinical evaluation.

Chemistry

Synthesis of aryl(heteryl) bromide/iodides 2c, 2j, 2n, 2o

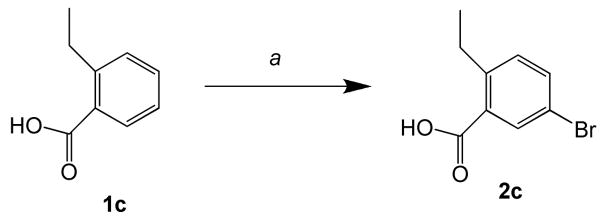

2-Ethyl-5-bromobenzoic acid 2c was isolated in 14% yield by treatment of 2-ethylbenzoic acid 1c with bromine in the presence of iron powder at room temperature for48 h and at 55°C for 2 h (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of 2-ethyl-5-bromobenzoic acid 2ca.

aReagents and conditions: (a) Br2/Iron (powder), room temperature to 50°C, 14%.

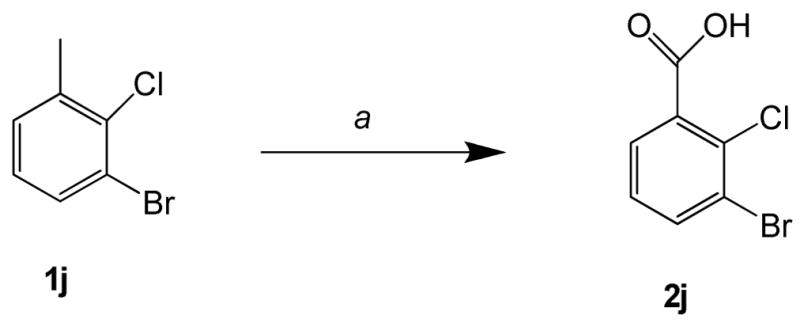

3-Bromo-2-chlorobenzoic acid 2j33 was synthesized in 49% yield by the oxidation of 3-bromo-2-chlorotoluene with KMnO4 in water for 24 h at reflux temperature (Scheme 2).

Scheme 2. Synthesis of 3-bromo-2-chlorobenzoic acid 2ja.

aReagents and conditions: (a) KMnO4, H2O, reflux, 24 h, 49%.

2-Bromo-5-iodonicotinic acid 2n was synthesized by treatment of 2,5-dibromo-3-picoline 1n with i-propylmagnesium chloride in the presence of I2 in tetrahydrofuran (THF) at room temperature for 24 h, followed by oxidation34 using KMnO4 in water for 48 h at reflux temperature (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3. Synthesis of 2-bromo-5-iodonicotinic acid 2na.

a Reagents and conditions: (a) i-PrMgCl, I2, THF, rt, 24 h, 55%; (b) KMnO4, H2O, reflux, 48 h, 14%.

4-Methyl-5-iodonicotinic acid 2o was synthesized from 3-bromo-5-(4,4-dimethyl-1,3-oxazolin-2-yl)pyridine 1o. First, 3-bromo-5-(4,4-dimethyl-1,3-oxazolin-2-yl)pyridine 1o20 was treated with MeI in the presence of lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) at −78°C for 1 h and for 1 h at room temperature to afford 3-bromo-4-methyl-5-(4,4dimethyl-1,3-oxazolin-2-yl)pyridine 3o in 76% yield. Reaction of 3-bromo-4-methyl-5-(4,4-dimethyl-1,3-oxazolin-2-yl)pyridine 3o with i-propylmagnesium chloride in the presence of I2 in THF at room temperature for 24 h, followed by hydrolysis gave 4-methyl-5-iodonicotinic acid 2o (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Synthesis of 4-methyl-5-iodonicotinic acid 2oa.

aReagents and conditions: (a) LDA, MeI, −78°C, 1 h, 76%; (b) i-PrMgCl, I2, THF, rt, 24 h, 45%; (c) 5 N HCl, reflux, 24 h, 84%.

Synthesis of 3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one 6

3-Phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one 6 was synthesized by modification of a literature procedure.21 Phenylethylamine 5 was treated with CS2 in diethyl ether at 0–5°C, followed by treatment with chloroacetic acid under reflux for 1 h to give 3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one 6 in 56% yield (Scheme 5).

Scheme 5. Synthesis of 3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-4-one 6a.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (i) CS2, Et2O, 0–5°C, 0.5 h; (ii) ClCH2COOH, EtOH, 1 h, reflux, 56%.

Synthesis of 2-aryl 5-formylfurans 8

2-Aryl 5-formylfurans 8 were synthesized by palladium-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling22,23 of aryl(heteryl) bromide/iodide with aryl(heteryl) boronic acids. 2-Aryl 5-formylfurans 8a–o were obtained (i) by coupling of 5-formyl-2-furylboronic acid 7 with corresponding aryl(heteryl) bromide/iodide 2b–d, f–o to give 8b–d, f–o (28–80% yield) by a modified literature method;24 or (ii) by reaction of 5-bromofuran-2-carboxaldehyde 9 with 3-carboxyphenylboronic acid 10a,e by a slight modifications to Bumagin’s method25 to give 8a,e (59–89% yield) (Scheme 6, Table 1). Suzuki-Miyaura coupling did not occur when the bromo analogues of 2i, 2n, 2o were used instead of aryl(heteryl) iodide 2i, 2n, 2o. All new compounds were characterized by1H, 13C NMR spectroscopy and elemental analysis.

Scheme 6. Synthesis of 2-Aryl 5-formylfurans 8a,b.

aReagents and conditions: (a) (PPh3)2PdCl2, Na2CO3 (aq), EtOH-DME (1:1), 50°C, 28–80%; (b) Pd(OAc)2, Na2CO3,H2O, rt, 59–89%.

bFor designation of X, R and R1 in 2, 8 and 10 see Table 1.

Table 1.

Preparation of 2-aryl 5-formylfurans 8

| Product 8 | X of 2, 8 and 10 | R of 2, 8 and 10 | R1 of 2, 8 and 10 | Reaction time, h | Yield (%) of 8a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8a | CH | H | H | 1.5 | 89 |

| 8b | CH | CH3 | H | 8.0 | 60 |

| 8c | CH | C2H5 | H | 7.0 | 68 |

| 8d | CH | Cl | H | 15 | 51b |

| 8e | CH | F | H | 1.5 | 59 |

| 8f | CH | OH | H | 7.0 | 67 |

| 8g | CH | OCH3 | H | 3.5 | 52 |

| 8h | CH | H | CH3 | 1.0 | 80 |

| 8i | CH | Br | H | 16.0 | 47 |

| 8j | CH | H | Cl | 16.0 | 49 |

| 8k | CH | H | F | 7.5 | 74 |

| 8l | N | H | H | 28.0 | 40 |

| 8m | N | Cl | H | 28.0 | 28 |

| 8n | N | Br | H | 16.0 | 31 |

| 8o | N | H | CH3 | 16.0 | 56 |

Isolated yields.

Crude yield and used without purification.

Synthesis of 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans 11

Knoevenagel condensation26–28 of N-substituted rhodanine 6 with aldehydes 8a–o in ethanol in the presence of catalytic amount of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine at 78°C for 1.5–12.5 h gave 11a-o (38–76%) (Scheme 7, Table 2). Novel 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans 11a-o were characterized by 1H, 13C NMR spectroscopy and elemental analysis.

Scheme 7. Synthesis of 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-ylidenemethyl)furans 11a,b.

Reagents and conditions: (a) ethanol, cat. 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine, reflux, 38–76%.

Table 2.

Preparation of 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-ylidenemethyl)furans 11a–o

| Product 11 | X of 11 | R of 11 | R1 of 11 | Reaction time, h | Yield (%) of 11a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11a | CH | H | H | 1.5 | 52 |

| 11b | CH | CH3 | H | 1.5 | 57 |

| 11c | CH | C2H5 | H | 3.0 | 48 |

| 11d | CH | Cl | H | 3.0 | 60 |

| 11e | CH | F | H | 1.5 | 71 |

| 11f | CH | OH | H | 12.5 | 50 |

| 11g | CH | OCH3 | H | 2.0 | 56 |

| 11h | CH | H | CH3 | 1.0 | 38 |

| 11i | CH | Br | H | 6.0 | 54 |

| 11j | CH | H | Cl | 9.0 | 58 |

| 11k | CH | H | F | 5.0 | 65 |

| 11l | N | H | H | 2.0 | 48 |

| 11m | N | Cl | H | 3.0 | 49 |

| 11nb | N | Br | H | 10.0 | 74 |

| 11o | N | H | CH3 | 10.0 | 76 |

Isolated yields

one equivalent of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine was used

Conclusion

In conclusion, we have designed and synthesized a series of novel 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans 11a–o by Suzuki-Miyaura cross coupling, followed by Knoevenagel condensation. These molecules exhibited highly potent anti-HIV-1 activity. The most promising compounds are 11a, 11b, and 11d which have the lowest EC50 (70 – 74 nM) which inhibited replication by laboratory-adapted and primary HIV-1 strains at <100 nM with selectivity indexes ranging from 330 to 440, suggesting that these compounds can be used as a lead for developing novel small molecule HIV fusion/entry inhibitors for treatment of HIV/AIDS patients who have failed to respond to current antiretroviral therapeutics.

Experimental Section

Chemistry

Aryl(heteryl) bromide/iodides 2b, 2d–i, 2k–m, 9 and aryl boronic acids 10a, 10e were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Aryl(heteryl) bromide/iodides 2c, 2j, 2n, 2o and 3-phenethyl-2-thioxo-thiazolidin-4-one 6 were synthesized and complete details of the synthesis, compounds spectral data were given in the supporting information. 5-Formyl-2-furanboronic acid 7 was synthesized according to a literature method.29 Melting points were determined using a capillary melting point apparatus equipped with a digital thermometer and are uncorrected. 1H (300 MHz) and 13C (75 MHz) NMR spectra were recorded in DMSO-d6 (with tetramethylsilanes as the internal standard), unless otherwise stated. Data are reported as follows: chemical shift, multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, br s = broad, m = multiplet), coupling constants (J values) are expressed in Hz. Elemental analyses were performed on a Carlo Erba EA-1108 instrument. All the reactions were performed in flame dried glassware. The solvents (ethylene glycol dimethyl ether (DME) and THF) were dried by the usual methods and distilled before use. Purity of compounds was determined by elemental analyses and/or HPLC; purity of target compounds was ≥ 95% except otherwise noted. Analytical HPLC analyses were performed on Shimadzu SPD-20-A using a Whelk-O1 column with detection at 254 nm, a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min and methanol as the eluting solvent. Column chromatography was performed on silica gel 200–425 mesh.

General procedure for preparation of 3-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)benzoic acids (8a and 8e)

5-Bromofuran-2-carbaldehyde 9 (0.44 g, 2.5 mmol), sodium carbonate (0.79 g, 7.5 mmol) and 3-carboxyphenylboronic acid 10 (2.75 mmol) were suspended in degassed water (12.5 mL) under nitrogen. Palladium acetate (5.6 mg, 0.025 mmol) was added to this mixture, which was stirred at room temperature for 1.5 h. The slurry was dissolved in water (100 mL) and filtered through celite. The filtrate was acidified with HCl and the precipitate was filtered and washed with water to give corresponding 5-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)benzoic acid 8a, 8e. Analytical samples were obtained by recrystallization from alcohol.

3-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)benzoic acid (8a)

Grey microcrystals, mp 264–266 °C (2-propanol) (lit.30 mp 266–267 °C); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.63 (s, 1H), 8.37 (br s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 7.68–7.62 (m, 2H), 7.41 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 178.3, 166.9, 157.2, 152.0, 131.9, 130.3, 129.8, 129.3, 129.1, 125.4, 109.7, 108.3. Anal. Calcd for C12H8O4: C, 66.67; H, 3.73; Found: C, 66.40; H, 3.65.

2-Fluoro-5-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)benzoic acid (8e)

White microcrystals, mp 231–233 °C (ethanol); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.64 (s, 1H), 8.31 (dd, J = 6.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.17–8.12 (m, 1H), 7.68 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (dd, J = 10.5, 8.8 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 178.1, 164.5 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1C), 161.5 (d, J = 261.1 Hz, 1C), 156.3, 151.9, 131.2, (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1C), 128.2, 125.3 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1C), 120.3 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1C), 118.3 (d, J = 23.5 Hz, 1C), 109.4. Anal. Calcd for C12H7FO4: C, 61.54; H, 3.01; Found: C, 61.35; H, 3.24.

General procedure for the preparation of 3-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)benzoic and -nicotinic acids (8b–d, f–o)

A mixture of aryl(heteryl) bromide/iodide 2b–d, f–o (2.3 mmol), 5-formyl-2-furanboronic acid 7 (0.42 g, 3.0 mmol), and (Ph3P)2PdCl2 (84.2 mg, 0.12 mmol) in DME (7.0 mL), ethanol (7.0 mL) and 2 M aqueous Na2CO3 (6.9 mL, 13.8 mmol of Na2CO3) was flushed with nitrogen for 5 min. and heated at 50°C for 3.5–28 h (reaction time is given in Table 1) under nitrogen atmosphere. The solvents were removed under reduced pressure, the residue was dissolved in water (20 mL), the mixture obtained was filtered through celite and the filtrate was neutralized with 2 N hydrochloric acid. The solids were filtered, washed with water, dried and recrystalized from ethanol to give 3-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)benzoic and -nicotinic acids 8b–d, f–o.

5-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)-2-methylbenzoic acid (8b)

Brownish microcrystal, mp 236–238°C (ethanol); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.63 (s, 1H), 8.28 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.95 (dd, J =7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 2.58 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 177.9, 168.1, 157.3, 151.7, 140.7, 132.6, 131.4, 128.0, 126.5, 126.3, 125.4, 108.9, 21.2. Anal. Calcd for C13H10O4: C, 67.82; H, 4.38; Found: C, 67.60; H, 4.47.

5-(5-Formyl-furan-2-yl)-2-ethylbenzoic acid (8c)

Brown prisms, mp 161–163°C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.63 (s, 1H), 8.23 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (dd, J = 8.0, 1.9 Hz, 1H); 7.67 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 2.97 (q, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 1.19 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 177.9, 168.3, 157.4, 151.7, 146.4, 131.4, 131.2, 128.0, 126.4, 126.3, 125.5, 109.0, 26.7, 15.8. Anal. Calcd for C14H12O4: C, 68.85; H, 4.95; Found: C, 68.51; H, 5.04.

5-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)-2-hydroxybenzoic acid (8f)

Brown microcrystals, mp 245–247°C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.59 (s, 1H), 8.24 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.03 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.23 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.11 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 177.5, 171.3, 162. 0, 157.6, 151.4, 132.3, 126.7, 125.8, 120.1, 118.3, 113.8, 107.7. Anal. Calcd for C12H8O5: C, 62.08; H, 3.47; Found: C, 61.67; H, 3.49.

5-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)-2-methoxybenzoic acid (8g)

Yellowish microcrystals, mp 220–222 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d 6) δ 9.59 (s, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.02 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.65 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.26 (m, 2H), 3.90 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 177.6, 166.8, 159.0, 157.6, 151.4, 129.7, 127.3, 125.8, 122.1, 120.8, 113.3, 107.9, 56.1. Anal. Calcd for C13H10O5: C, 63.42; H, 4.09; Found: C, 63.22; H, 4.04.

3-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)-2-methylbenzoic acid (8h)

Yellow microcrystals, mp 140–142 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.71 (s, 1H), 8.01 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.89 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.42–7.36 (m, 2H), 6.75 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.74 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 177.1, 169.9, 158.3, 151.5, 136.7, 133.1, 131.4, 130.9, 130.1, 125.3, 112.0, 18.3. Anal. Calcd for C13H10O4: C, 67.82; H, 4.38; Found: C, 67.54; H, 4.32.

5-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)-2-bromobenzoicacid hemihydrate (8i)

Brown microcrystals; mp 161 °C (decom.); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.65 (s, 1H), 8.18 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.90–7.87 (m, 2H), 7.68 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 178.4, 167.0, 156.2, 152.1, 134.9, 128.4, 128.2, 126.6, 125.4, 121.1, 110.3. Anal. Calcd for C12H7BrO4·½H2O: C, 47.40; H, 2.65. Found: C, 47.17; H, 2.52.

3-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)-2-chloro-benzoic acid (8j)

Yellowish microcrystal, mp 192–195 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.69 (s, 1H), 8.00 (dd, J = 1.5, 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.76 (dd, J = 1.5, 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.70 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 178.6, 167.3, 154.1, 151.9, 135.3, 131.3, 130.5, 128.7, 128.1, 127.9, 124.5, 114.3. Anal. Calcd for C12H7ClO4: C, 57.51; H, 2.82; Found: C, 57.51; H, 2.85.

3-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)-2-fluorobenzoic acid (8k)

Orange microcrystal, mp 260–262 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.69 (s, 1H), 8.15–8.10 (m, 1H), 7.96–7.91 (m, 1H), 7.72 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.22 (t, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 178.3, 164.6 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1C), 157.7 (d, J = 264.5 Hz, 1C), 151.6, 151.6 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1C), 132.7 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1C), 131.0 (d, J = 2.9 Hz, 1C), 125.1 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1C), 125.0 (br s, 1C), 120.8 (d, J = 10.3 Hz, 1C), 118.1 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1C), 113.3 (d, J = 12.0 Hz, 1C). Anal. Calcd for C12H7FO4: C, 61.54; H, 3.01; Found: C, 61.53; H, 2.99.

3-(5-Formylfuran-2-yl)nicotinic acid (8l)

Orange microcrystals, mp 287–289 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.69 (s, 1H), 9.31 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 9.08 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 8.62 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.73 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.61 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 178.5, 165.9, 154.5, 152.6, 150.5, 149.7, 132.5, 127.1, 125.1, 125.0, 111.1. Anal. Calcd for C11H7NO4: C, 60.83; H, 3.25; N, 6.45; Found: C, 60.47; H, 3.37; N, 6.14.

2-Chloro-5-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)nicotinic acid (8m)

Orange microcrystals, mp 215–217 °C; NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.68 (s, 1H), 9.01 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.58 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 178.6, 165.5, 153.7, 152.6, 147.9, 147.4, 135.4, 129.5, 125.0, 124.5, 111.5. Anal. Calcd for C11H6ClNO4: C, 52.51; H, 2.40; N, 5.57; Found: C, 52.12; H, 2.58; N, 4.97.

2-Bromo-5-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)nicotinic acid (8n)

Yellow microcrystals; mp 200–210 °C (decom.); 1H NMR ((CD3)2CO) δ 9.81 (s, 1H), 9.07 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.65 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H); 13NMR ((CD3)2CO) δ 178.5, 165.9, 154.6, 154.2, 148.7, 140.5, 135.9, 131.6, 125.8, 124.2, 111.7. Anal. Calcd for C11H6BrNO4: C, 44.62; H, 2.04; N, 4.73. Found: C, 45.31; H, 2.23; N, 4.24.

4-Methyl-5-(5-formylfuran-2-yl)nicotinic acid hemihydrate (8o)

Yellow microcrystals; mp 180°C (decom.); 1H NMR ((CD3)2CO) δ 9.76 (s, 1H), 9.03 (s, 1H), 8.96 (s, 1H), 7.62 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.15 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 2.75 (s, 3H); 13NMR ((CD3)2CO) δ 178.5, 167.6, 156.0, 154.1, 152.4, 152.0, 147.1, 128.7, 127.6, 123.6, 114.4, 18.1; Anal. Calcd for C12H9NO4·½H2O C, 60.00; H, 4.20; N, 5.83. Found: C, 60.07; H, 3.86; N, 5.26.

General procedure for preparation of 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans (11a–o)

A mixture of 3-(5-formyl-furan-2-yl)benzoic acid 8 (0.75 mmol), 3-phenethyl-2-thioxo-thiazolidin-4-one 6 (0.18 g, 0.75 mmol) and 2 drops of 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine in 7 mL of ethanol was heated under reflux for 2.0–12.0 h (reaction time is given in Table 2). After cooling to 40–45 °C, the solid obtained was filtered and washed with cooled ethanol to give corresponding 2-aryl 5-(4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidinylidenemethyl)furans (11a–o).

3-{5-[4-Oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11a)

Yellow needles, mp 263–265 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.38 (s, 1H), 8.05 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.97 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.44 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 7.36 (d, J = 3.3 Hz, 1H), 7.30–7.23 (m, 5H), 4.22 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (t, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.7, 174.5, 166.7, 166.3, 156.9, 149.5, 137.6, 131.9, 129.8, 128.9, 128.7, 128.5, 128.4, 126.6, 124.9, 123.0, 118.9, 118.2, 111.0, 45.2, 32.1. Anal. Calcd for C23H17NO4S2: C, 63.43; H, 3.93; N, 3.22; Found: C, 63.21; H, 3.80; N, 3.20.

2-Methyl-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11b)

Yellow microcrystals, mp 297–298°C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.27 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.88 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.49 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.21 (m, 7H), 4.23 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.57 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.7, 168.1, 166.3, 157.2, 149.2, 140.2, 137.6, 132.7, 131.5, 128.7, 128.5, 127.2, 126.6, 126.4, 125.9, 123.2, 118.5, 118.3, 110.4, 45.3, 32.2, 21.2. Anal. Calcd for C24H19NO4S2: C, 64.12; H, 4.26; N, 3.12; Found: C, 63.85; H, 4.21; N, 3.02.

2-Ethyl-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11c)

Orange microcrystals, mp 251–253 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.22 (d, J = 1.92 Hz, 1H), 7.91 (dd, J = 8.1, 1.92 Hz, 1H), 7.63 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 7.36–7.29 (m, 4H), 7.24–7.21 (m, 3H), 4.22 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 3.00–2.93 (m, 4H), 1.20 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.7, 168.3, 166.3, 157.2, 149.3, 145.9, 137.6, 131.5, 131.3, 128.7, 128.5, 127.2, 126.6, 126.3, 125.9, 123.2, 118.5, 118.3, 110.4, 45.2, 32.2, 26.7, 15.8. Anal. Calcd for C25H21NO4S2: C, 64.77; H, 4.57; N, 3.02; Found: C, 64.66; H, 4.48; N, 3.04.

2-Chloro-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11d)

Orange microcrystals, mp 276–278 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.21 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.93 (dd, J = 8.5, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.75 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.48 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.21 (m, 3H), 4.23 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.6, 166.3, 166.3, 155.9, 149.8, 137.6, 132.6, 131.9, 131.8, 128.7, 128.6, 127.6, 127.5, 126.7, 126.3, 123.0, 119.2, 118.1, 111.6, 45.3, 32.2. Anal. Calcd for C23H16ClNO4S2: C, 58.78; H, 3.43; N, 2.98; Found: C, 59.04; H, 3.28; N, 2.95.

2-Fluoro-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11e)

Yellow microcrystals, mp 286–288 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.29 (dd, J = 6.7, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.07–8.02 (m, 1H), 7.62 (s, 1H), 7.53 (dd, J = 10.4, 8.9 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.35 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.21 (m, 5H), 4.22 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.6, 166.3, 164.4 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1C), 161.1 (d, J = 260.5 Hz, 1C), 156.1, 149.5, 137.6, 130.2 (d, J = 9.2 Hz, 1C), 128.7, 128.5, 127.7, 126.6, 125.2 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1C), 123.1, 120.3 (d, J = 11.5 Hz, 1C), 118.8, 118.4 (d, J = 23.5 Hz,1C), 118.2, 110.8, 45.2, 32.1. Anal. Calcd for C23H16FNO4S2: C, 60.91; H, 3.56; N, 3.09; Found: C, 60.90; H, 3.38; N, 3.06.

2-Hydroxy-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11f)

Orange microcrystals, mp 257–259 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.24 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.00 (dd, J = 8.7, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.59 (s, 1H), 7.34–7.21 (m, 7H), 7.14 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H), 4.22 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H). Anal. Calcd for C23H17NO5S2: C, 61.18; H, 3.79; N, 3.10; Found: C, 61.02; H, 3.75; N, 3.09.

2-Methoxy-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11g)

Orange microcrystals, mp 221–223 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.14 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.99 (dd, J = 8.8, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.40–7.31 (m, 5H), 7.28–7.24 (m, 3H), 4.26 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.93 (s, 3H), 2.98 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.6, 166.8, 166.3, 158.6, 157.5, 148.8, 137.7, 128.9, 128.7, 128.5, 126.8, 126.6, 123.5, 122.3, 120.8, 118.3, 117.7, 113.5, 109.4, 56.1, 45.2, 32.2. Anal. Calcd for C24H19NO5S2: C, 61.92; H, 4.11; N, 3.01; Found: C, 61.68; H, 4.02; N, 3.02.

2-Methyl-3-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2- yl}-benzoic acid (11h)

Red microcrystals, mp 248–250 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 7.85 (d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 7.78 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.69 (s, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.31–7.24 (m, 5H), 7.13 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H), 2.96 (t, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 2.61 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.7, 166.3, 157.3, 149.2, 137.6, 135.0, 130.4, 130.0, 128.7, 128.5, 126.6, 126.3, 122.7, 118.8, 118.4, 114.5, 45.3, 32.1, 18.5. Anal. Calcd for C24H19NO4S2: C, 64.12; H, 4.26; N, 3.12; Found: C, 63.75; H, 4.42; N, 3.14.

2-Bromo-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11i)

Deep red microcrystals; mp 241 °C (decom.); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.20 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7. 94–7.98 (m, 1H), 7.86–7.89 (m, 1H), 7.69 (s, 1H), 7.54 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.24–7.38 (m, 6H), 4.27 (t, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 3.00 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.7, 167.1, 166.4, 156.0, 149.8, 137.7, 135.1, 135.0, 128.8, 128.6, 128.0, 127.5, 126.7, 126.0, 123.1, 120.4, 119.3, 118.2, 111.7, 45.4, 32.2. HRMS: (DIP-CI-MS) calcd for C23H16BrNO4S2: for [M+H] is 513.9779 and found 513.9782. Analytical HPLC: 98.8%, tR = 3.38 (tracing: 0.7%, tR = 4.19)

2-Chloro-3-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11j)

Orange microcrystals, mp 258–260 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.0 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 7.75–7.64 (m, 3H), 7.47 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 3.6 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.21 (m, 3H), 4.23 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.9, 167.4, 166.5, 154.0, 149.7, 137.8, 135.7, 130.3, 130.0, 128.9, 128.7, 128.5, 128.1, 127.4, 126.8, 122.5, 120.0, 118.3, 115.9, 45.5, 32.3. Anal. Calcd for C23H16ClNO4S2: C, 58.78; H, 3.43; N, 2.98; Found: C, 58.40; H, 3.39; N, 2.88.

2-Fluoro-3-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-benzoic acid (11k)

Orange microcrystals, mp 262–264 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.00–7.95 (m, 1H), 7.87–7.81 (m, 1H), 7.65 (s, 1H), 7.50 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.25–7.18 (m, 4H), 4.22 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (t, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.7, 166.3, 164.9, 157.2 (d, J = 263.4 Hz, 1C), 151.6, 149.3, 137.6, 132.0, 129.4 (br s, 1C), 128.7, 128.6, 126.7, 125.1 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1C), 122.9, 122.2 (br d, J = 10.9 Hz, 1H), 119.6, 118.0, 117.9 (d, J = 14.9 Hz, 1C), 114.6 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1C), 45.3, 32.1. Anal. Calcd for C23H16FNO4S2: C, 60.91; H, 3.56; N, 3.09; Found: C, 61.13; H, 3.52; N, 3.11.

5-{5-[4-Oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-nicotinic acid (11l)

Orange microcrystals, mp 259–261 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 9.14 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 9.03 (d, J = 1.9 Hz, 1H), 8.58 (t, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.67 (s, 1H), 7.56 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.40 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.22 (m, 5H), 4.24 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 2. 97 (t, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.6, 166.3, 166.2, 154.9, 150.2, 150.0, 147.3, 137.6, 131.6, 130.9, 128.7, 128.5, 126.6, 124.4, 122.8, 119.4, 118.1, 111.8, 45.3, 32.1. Anal. Calcd for C22H16N2O4S2: C, 60.54; H, 3.69; N, 6.42; Found: C, 60.44; H, 3.65; N, 6.28.

2-Chloro-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-nicotinic acid (11m)

Orange microcrystals, mp 246–248 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.71 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 8.12 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 7.66 (s, 1H), 7.51 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.38 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.29 (m, 2H), 7.24–7.22 (m, 3H), 4.23 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.6, 166.6, 166.3, 154.5, 149.9, 146.4, 143.1, 138.3, 137.6, 132.1, 128.7, 128.6, 126.7, 123.8, 122.8, 119.4, 118.1, 11.9, 45.3, 32.2. Anal. Calcd for C22H15 ClN2O4S2: C, 56.11; H, 3.21; N, 5.95; Found: C, 56.01; H, 3.01; N, 5.60.

2-Bromo-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-nicotinic acid hemi 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine dihydrate (11n)

Orange microcrystals; mp 200–205 °C; 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.79 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 8.41 (br s, 1H), 8.25 (d, J = 2.4 Hz, 1H), 7.64 (s, 1H), 7.55 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.37 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.21 (m, 5H), 4.22 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.95 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H); 13NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.6, 166.7, 166.3, 153.8, 150.2, 145.3, 138.1, 137.6, 132.6, 128.7, 128.6, 126.7, 124.2, 122.7, 119.8, 118.0, 112.6, 55.6, 45.3. Anal. Calcd for C22H15S2BrN2O4·½C9H19N·2H2O: C, 52.69; H, 4.42; N, 5.80. Found: C, 52.84; H, 4.02; N, 5.32.

4-Methyl-5-{5-[4-oxo-3-phenethyl-2-thioxothiazolidin-5-ylidenemethyl]furan-2-yl}-nicotinic acid (11o)

Brown microcrystals; mp 270 °C (decom.); 1H NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 8.97 (s, 1H), 8.89 (s, 1H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.43 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 7.34–7.22 (m, 6H), 4.23 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 2.96 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 2.68 (s, 3H); 13C NMR (DMSO-d6) δ 193.6, 167.6, 166.3, 154.4, 150.2, 150.0, 144.4, 137.7, 128.8, 128.7, 128.6, 126.7, 126.0, 122.3, 119.6, 118.2, 115.5, 45.3, 32.2, 18.1. Anal. Calcd for C23H18S2N2O4: C, 61.32; H, 4.03; N, 6.22. Found: C, 61.06; H, 4.05; N, 5.94.

Molecular modeling and docking of 11d onto the gp41 hydrophobic cavity

We used the automated dockingsoftware Glide (Schrödinger, Portland, OR), this applies a two-stage scoring process to sort out the best conformations and orientations of the ligand (defined as pose) based on its interaction pattern with the receptor. The starting point of the docking simulation was the X-ray structure of the gp41 core (1AIK) available from the protein data bank (PDB) at the “Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics (RCSB)”; this has been extensively used in our research program. Three-dimensional coordinates of the ligands, their isomeric, ionization and tautomeric states were generated using the LigPrep (including Ionizer) module from Schrödinger. The protein was prepared using the protein preparation tool available in the software. A grid file encompassing the area in the cavity that contains information on the properties of the associated receptor was created. Conformational flexibility of the ligands was handled via an exhaustive conformational search. We used Schrödinger’s proprietary GlideScore scoring function in standard precision (SP) and extra precision (XP) mode to score the optimized poses. The poses were selected based on the salt-bridge and other hydrophobic and hydrogen bond interactions.

Determination of the inhibitory activity of the compounds on HIV-1 replication

The inhibitory activity of compounds on HIV-1IIIB replication in MT-2 cells was determined as previously described.18 In brief, 1×104 MT-2 cells were infected with an HIV-1IIIB strain (100 TCID50) in 200 μL RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS in the presence or absence of a test compound at graded concentrations overnight. Then, the culture supernatants were removed and fresh media containing no test compounds were added. On the fourth day post-infection, 100 μL of culture supernatants were collected from each well, mixed with equal volumes of 5% Triton X-100 and assayed for p24 antigen, which was quantitated by ELISA. Briefly, wells of polystyrene plates (Immulon 1B, Dynex Technology, Chantilly, VA) were coated with HIV immunoglobulin (HIVIG), which was prepared from plasma of HIV-seropositive donors with high neutralizing titers against HIV-1IIIB, in 0.085 M carbonate-bicarbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 4 °C overnight, followed by washing with buffer (0.01 M PBS containing 0.05% Tween-20) and blocking with PBS containing 1% dry fat-free milk (Bio-Rad, Inc., Hercules, CA). Virus lysates were added to the wells and incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. After extensive washes, anti-p24 mAb (183-12H-5C), biotin-labeled anti-mouse IgG1 (Santa Cruz Biotech., Santa Cruz, CA), streptavidin-labeled horseradish peroxidase (Zymed, S. San Francisco, CA), and the substrate 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) were added sequentially. Reactions were terminated by addition of 1N H2SO4. Absorbance at 450 nm was recorded in an ELISA reader (Ultra 386, TECAN, Research Triangle Park, NC). Recombinant protein p24 purchased from US Biological (Swampscott, MA) was included for establishing standard dose response curves. Each sample was tested in triplicate. The percentage of inhibition of p24 production was calculated as previously described.31 EC50 were calculated using a computer program, designated CalcuSyn,32 kindly provided by Dr. T. C. Chou (Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, New York, NY).

To determine the potential effect of light on the bioactivity of the compounds, we also tested these compounds under exclusion of light. Briefly, the compound solutions were prepared and added to the virus (HIV-1 IIIB) and MT-2 cells in the biosafety hood with the light turned off. Then the plates were wrapped with foil before they were put in the CO2 incubator. The other procedures are the same as described above.

Inhibitory activity of compounds on infection by a primary HIV-1 isolate, 94UG103 (X4R5, clade A), was determined as previously described.18 Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were isolated from the blood of healthy donors at the New York Blood Center by standard density gradient centrifugation using Histopaque-1077 (Sigma). The cells were plated in 75 cm2 plastic flasks and incubated at 37 °C for 2 hrs. The nonadherent cells were collected and resuspended at 5 × 106 in 10 ml RPMI-1640 medium containing 10% FBS, 5 μg/ml PHA and 100 U/ml IL-2 (Sigma), followed by incubation at 37 °C for 3 days. The PHA-stimulated cells were infected with 94UG103 at 0.01 multiplicity of infection (MOI) in the absence or presence of a compound at graded concentrations. Culture media were changed every 3 days. The supernatants were collected 7 days post-infection and tested for p24 antigen by ELISA as described above. The percent inhibition of p24 production and EC50 values were calculated as described above.

Assessment of in vitro cytotoxicity

The in vitro cytotoxicity of compounds on MT-2 cells was measured by XTT assay.19 Briefly, 100 μL of the test compound at graded concentrations were added to equal volumes of cells (5×105/mL) in wells of 96-well plates. After incubation at 37 °C for 4 days, 50 μL of XTT solution (1 mg/mL) containing 0.02 μM of phenazine methosulphate (PMS) was added. After 4 h, the absorbance at 450 nm was measured with an ELISA reader. The CC50 (concentration for 50% cytotoxicity) values were calculated using the CalcuSyn program.32

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grant RO1 AI46221 and the intramural fund from the New York Blood Center. We thank Dr. C. D. Hall for helpful discussions.

Abbreviations

- CHR

C-terminal heptad repeat

- Env

envelope glycoprotein

- NHR

N-terminal heptad repeat

- XTT

sodium 3′-[1-(phenylamino)-carbonyl]-3,4-tetrazolium-bis(4-methoxy-6-nitro)bezenesulfonic acid hydrate

- RTI

reverse transcriptase inhibitors

- PI

protease inhibitors

- HAART

highly active antiretroviral therapy

- mAb

monoclonal antibody

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- LDA

lithium diisopropylamide

- i-PrMgCl

i-propylmagnesium chloride

- EtOH-DME

Ethyl alcohol-Ethylene glycol dimethyl ether

- RCSB

Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- PMS

phenazine methosulphate

Footnotes

Dedicated to Professor Corwin Hansch on his 91st Anniversary in appreciation of his pioneering achievements

This manuscript is part of the MEDI Centennial 2009 special issue of the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

Supporting Information Available: Experimental details, spectral data for aryl(heteryl) bromide/iodides 2c, 2j, 2n, 2o, intermediates 3n, 3o, 4o, 3-phenethyl-2-thioxo-thiazolidin-4-one 6, and the inhibition of the compounds 11a, 11b, and 11d on infection by HIV-1 IIIB and 94UG103 and chemical structures of 12 (NB-2) and 13 (NB-64). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Reference and Notes

- 1.Fauci AS. 25 years of HIV. Nature. 2008;453:289–290. doi: 10.1038/453289a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walker BD, Burton DR. Towards an AIDS Vaccine. Science. 2008;320:760–764. doi: 10.1126/science.1152622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Clercq E. Antiviral drugs in current clinical use. J Clin Virol. 2004;30:115–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson VA, Brun-Vezinet F, Clotet B, Conway B, D’Aquila RT, Demeter LM, Kuritzkes DR, Pillay D, Schapiro JM, Telenti A, Richman DD. Drug resistance mutations in HIV-1. Top HIV Med. 2003;11:215–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richman DD, Morton SC, Wrin T, Hellmann N, Berry S, Shapiro MF, Bozzette SA. The prevalence of antiretroviral drug resistance in the United States. AIDS. 2004;18:1393–1401. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000131310.52526.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carr A, Cooper DA. Adverse effects of antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2000;356:1423–1430. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02854-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berger EA. HIV entry and tropism: the chemokine receptor connection. AIDS. 1997;11:3–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chan DC, Kim PS. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell. 1998;93:681–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu S, Wu S, Jiang S. HIV entry inhibitors targeting gp41: from polypeptides to small-molecule compounds. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:143–162. doi: 10.2174/138161207779313722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang S, Lin K, Strick N, Neurath AR. HIV-1 inhibition by a peptide. Nature. 1993;365:113. doi: 10.1038/365113a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wild CT, Shugars DC, Greenwell TK, McDanal CB, Matthews TJ. Peptides corresponding to a predictive α-helical domain of human immunodeficiency virus type1 gp41 are potent inhibitors of virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9770–9774. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lu M, Blacklow SC, Kim PS. A trimeric structural domain of the HIV-1 transmembrane glycoprotein. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2:1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/nsb1295-1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan DC, Fass D, Berger JM, Kim PS. Core structure of gp41 from the HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;89:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison SC, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Atomic Structure of the Ectodomain from HIV-1 gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kilby JM, Eron JJ. Novel therapies based on mechanisms of HIV-1 cell entry. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2228–2238. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lalezari JP, Henry K, O’Hearn M, Montaner JSG, Piliero PJ, Trottier B, Walmsley S, Cohen C, Kuritzkes DR, Eron JJ, Jr, Chung J, DeMasi R, Donatacci L, Drobnes C, Delehanty J, Salgo M. Enfuvirtide, an HIV-1 fusion inhibitor, for drug-resistant HIV infection in north and south America. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2175–2185. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu S, Boyer-Chatenet L, Lu H, Jiang S. Rapid and automated fluorescence-linked immunosorbent assay for high throughput screening of HIV-1 fusion inhibitors targeting gp41. J Biomol Screening. 2003;8:685–693. doi: 10.1177/1087057103259155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang S, Lu H, Liu S, Zhao Q, He Y, Debnath AK. N-substituted pyrrole derivatives as novel human immunodeficiency virus type 1 entry inhibitors that interfere with the gp41 six-helix bundle formation and block virus fusion. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4349–4359. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.11.4349-4359.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debnath AK, Radigan L, Jiang S. Structure-based identification of small molecule antiviral compounds targeted to the gp41 core structure of the human immunodecifiency virus type 1. J Med Chem. 1999;42:3203–3209. doi: 10.1021/jm990154t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robert N, Bonneau A, Hoarau C, Marsais F. Unusual sterically controlled regioselective lithiation of 3-bromo-5-(4,4′-dimethyl)oxazolinylpyridine. Straightforward access to highly substituted nicotinic acid derivatives. Org Lett. 2006;8:6071–6074. doi: 10.1021/ol062556i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buck JS, Leonard CS, Rhodanines I. Derivatives of β-phenylethylamines. J Am Chem Soc. 1931;53:2688–2692. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyaura N, Suzuki A. Palladium-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions of organoboron compounds. Chem Rev. 1995;95:2457–2483. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kotha S, Lahiri K, Kashinath D. Recent applications of the Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction in organic synthesis. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:9633–9695. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosoya T, Aoyama H, Ikemoto T, Kihara Y, Hiramatsu T, Endo M, Suzuki M. Dantrolene analogues revisited: General synthesis and specific functions capable of discriminating two kinds of Ca2+ release from Sarcoplasmic Reticulum of mouse skeletal muscle. Bioorg Med Chem. 2003;11:663–673. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00600-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bumagin NA, Bykov VV. Ligandless palladium catalyzed reactions of arylboronic acids and sodium tetraphenylborate with aryl halides in aqueous media. Tetrahedron. 1997;53:14437–14450. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee CL, Sim MM. Solid-phase combinatorial synthesis of 5-arylalkylidene rhodanine. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:5729–5732. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lohray BB, Bhushan V, Rao PB, Madhavan GR, Murali N, Rao KN, Reddy KA, Rajesh BM, Reddy PG, Chakrabarti R, Rajagopalan R. Novel indole containing thiazolidinedione derivatives as potent euglycemic and hypolipidaemic agents. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 1997;7:785–788. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh SP, Parmar SS, Raman K, Stenberg VI. Chemistry and Biological activity of thiazolidinones. Chem Rev. 1981;81:175–203. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parry PR, Bryce MR, Tarbit B. 5-Formyl-2-furylboronic acid as a versatile bifunctional reagent for the synthesis of π-extended heteroarylfuran systems. Org Biomol Chem. 2003;1:1447–1449. doi: 10.1039/b302767h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Korolev DN, Bumagin NA. Pd-EDTA as an efficient catalyst for Suzuki-Miyaura reactions in water. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:5751–5754. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhao Q, Ma L, Jiang S, Lu H, Liu S, He Y, Strick N, Neamati N, Debnath AK. Identification of N-phenyl-N′-(2,2,6,6-tetramethyl-piperidin-4-yl)-oxalamides as a new class of HIV-1 entry inhibitors that prevent gp120 binding to CD4. Virology. 2005;339:213–225. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chou TC, Hayball MP. CalcuSyn: Windows software for dose effect analysis. BIOSOFT; Ferguson, MO 63135, USA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gohier F, Mortier J. ortho-Metalation of Unprotected 3-bromo and 3-chlorobenzoic acids with hindered lithium dialkylamides. J Org Chem. 2003;68:2030–2033. doi: 10.1021/jo026514t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Setliff FL, Greene JS. Some 2,5- and 5,6-dihalonicotinic acids and their precursors. J Chem Engg Data. 1978;23:96–97. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.