Abstract

Nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2/caspase recruitment domain 15 (NOD2/CARD15) polymorphisms have been identified as risk factors of both Crohn's disease and graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. However, the role of these receptors of innate immunity in the pathophysiology of gastrointestinal GVHD is still poorly defined. Immunohistological features of intestinal GVHD were analysed in gastrointestinal biopsies from 58 patients obtained at the time of first onset of intestinal symptoms. The observed changes were correlated with concomitant risk factors and the presence of polymorphisms within the pathogen recognition receptor gene NOD2/CARD15. Intestinal GVHD was associated with a stage-dependent decrease in CD4 T cell infiltrates and an increase in CD8 T cells in the lamina propria; CD8 infiltrates correlated with extent of apoptosis and consecutive epithelial proliferation. The presence of NOD2/CARD15 variants in the recipient was associated with a significant loss of CD4 T cells: in a semiquantitative analysis, the median CD4 score for patients with wild-type NOD2/CARD15 was 1·1 (range 3), but only 0·4 (range 2) for patients with variants (P = 0·002). This observation was independent from severity of GVHD in multivariate analyses and could not be explained by the loss of forkhead box P3+ T cells. Our results suggest a loss of protective CD4 T cells in intestinal GVHD which is enhanced further by the presence of NOD2/CARD15 variants. Our study might help to identify more selective therapeutic strategies in the future.

Keywords: CD4, gastrointestinal GVHD, immunohistology, NOD2/CARD15

Introduction

Gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is the most severe and life-threatening manifestation of acute GVHD following allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT) in humans. Up to the present the exact mechanisms triggering intestinal GVHD are poorly understood: as in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [1,2], it is likely that the interaction of the intestinal flora with epithelial immune responses contributes to inflammatory signals that enhance the alloresponse. The first strong evidence was provided by van Bekkum in 1974, when he reported that mice grown under germfree conditions almost failed to develop GVHD after marrow transplantation and developed only delayed GVHD if a higher T cell number by adding splenocytes was infused [3]. Today, it is well accepted that triggering antigen-presenting cells (APC) by pathogen-associated microbial patterns (PAMPs) via Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and a large set of further receptors is an important first step in inflammation in both IBD and GVHD, and contributes to the initiation of an alloreaction in target organs of GVHD [4].

Our group added the observation that feeding mice with lactobacilli dampened intestinal inflammation and indeed altered the severity and time–course of intestinal GVHD; in addition, lactobacilli prevented translocation of intestinal bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes [5]. More recently, we demonstrated that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within an important receptor of innate immunity, the intracytoplasmatic nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2/caspase recruitment domain 15 (NOD2/CARD15), were associated with an increased risk of severe GVHD, treatment-related mortality [6,7] and further transplant-related complications such as bronchiolitis obliterans [8]. These associations suggest a further link in the pathophysiology of Crohn's disease and intestinal GVHD, at least with regard to initial inflammation, and may explain a clinically well-known but as yet unexplained individual susceptibility.

Functional consequences of NOD2/CARD15 variants in humans have been shown both in vitro and ex vivo in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: isolated monocytes and dendritic cells showed reduced capacity to release inflammatory cytokines in the presence of NOD2/CARD15 variants [9,10], epithelial cells revealed deficient clearance of bacteria [11] and most important for anti-bacterial defence, Wehkamp and colleagues reported strong reduction of human beta-defensin-2 production in epithelial cells [12].

In contrast, data on the functional relevance of NOD2/CARD15 SNPs in allogeneic SCT have not yet been reported. We have now tested the hypothesis that immunohistological features of intestinal GVHD reflecting different pathophysiological cellular functions might be altered by the presence of NOD2/CARD15 variants in recipients or donors. In a prospective study we examined gastrointestinal biopsies from 58 patients and found a major impact of NOD2/CARD15 on CD4 T cell infiltrates.

Material and methods

Patient characteristics

A total of 64 patients receiving an allogeneic peripheral stem cell graft were included. Immunosuppressive prophylaxis consisted of cyclosporin followed by a short course of methotrexate (MTX) in patients receiving standard conditioning and cyclosporin and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or MTX (n = 3) in patients receiving reduced intensity regimens. Further patient characteristics are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Post-transplant (n = 58) | |

|---|---|

| Age at SCT (years, ±standard error) | 48 (3) |

| Underlying disease | |

| Acute leukaemia | 30 |

| Myeloproliferation disease | 12 |

| Lymphoma | 12 |

| Myeloma | 4 |

| Donor | |

| HLAid.sibling | 28 |

| MUD | 30 |

| Conditioning | |

| Standard | 19 |

| RIC | 39 |

| NOD2/CARD15 status | |

| D & R wild-type | 29 |

| R variant | 12 |

| SNP 8/12/13 | 9/3/0 |

| D variant | 13 |

| SNP8/12/13 | 6/1/2 |

| R & D variant | 4 |

| SNP8/12/13 | 2/0/2 |

MUD: matched unrelated donor; RIC: reduced intensity conditioning; D: donor; R: recipient; SCT: stem cell transplantation; NOD2/CARD15: nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2/caspase recruitment domain 15; SNP: single nucleotide polymorphism.

Intestinal biopsies

In six patients, endoscopy was performed prior to transplantation because of a history of previous inflammatory bowel disease or acute gastroenteritis during preceding treatment. In the remaining 58 patients, biopsies from the lower gastrointestinal tract were obtained after allogeneic SCT at the time of first symptoms indicating intestinal GVHD. As intestinal symptoms occurred frequently after onset of skin GVHD or at the time of tapering of immunosuppressive treatment for previous GVHD in other organs, the majority of patients were receiving treatment with corticosteroids at the time of biopsy, and 15 patients were pretreated with additional etanercept (n = 4), anti-thymocyte globulin (ATG) (n = 5) or both (n = 6). Clinical gastrointestinal GVHD was graded according to Glucksberg, as modified by the 1994 consensus conference, and biopsies were grouped according to clinical stage of intestinal GVHD at the time of biopsies if histology confirmed GVHD. Infections were excluded by microbiological analysis of stool samples and by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for adenovirus, cytomegalovirus (CMV) and human herpes virus 6 (HHV6) in biopsies and blood.

Biopsies obtained from unaffected areas of surgical specimens obtained during resection of localized tumours served as controls.

Histological and immunohistological analysis

Tissue biopsies were fixed in 4% buffered formalin for at least 24 h and embedded in paraffin. Sections of approximately 2–3 µm thickness were cut from tissue blocks and stained with haematoxylin and eosin according to standard protocols. Histopathological analysis was performed without knowledge of the clinical data and specimens were examined in random order. Common histopathological features of GVHD, such as epithelial apoptosis, loss of crypts and cellular infiltrates for neutrophils, eosinophils and lymphocytes in general, were assessed separately for the epithelial area and the lamina propria.

Immunohistochemical studies were performed for the expression of CD4, CD8, CD68, MIB1a and FoxP3 using an avidin–biotin–peroxidase method with diaminobenzidine (DAB) chromogen. After antigen retrieval by microwave treatment immunohistochemistry was carried out in a NEXES immunostainer (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ, USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. As primary antibodies, mouse monoclonal antibodies were used at a dilution of 1 : 5 for CD4 (Ventana no. 250-2712), undiluted for CD8 (Ventana no. 760-4250), at a dilution of 1 : 100 for the macrophage marker CD68 (Dako MO876; Dako, Hamburg, Germany), at a dilution of 1 : 50 for the proliferation marker Mib1 (Dako M7240) and at a dilution of 1 : 100 for FoxP3 (eBioscience no. 14-4777-80; eBioscience, Frankfurt, Germany). After incubation for 24 h at 37°C slides were rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline and incubated with the second antibody (rabbit anti-mouse, 1 : 500, Ventana Medical Systems; Ventana, Illkirch, France) for 2 h at room temperature. Antibody binding was visualized with 0·05% DAB (Ventana Medical Systems) and 0·01% hydrogen peroxide. The material was rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline and counterstained with haematoxylin.

Statistical analysis

A semiquantitative score was chosen for reporting immunohistological analyses and histological changes: scoring of infiltrates ranged from 0 to 3, score 0 indicating only 0–1 cells/high power field (HPF); score 1 indicating 2–4 cells, score 2 indicating 5–7 and score 3 8–10 cells/HPF. At least 10 HPFs were analysed per section and, if available, at least two sections were analysed per biopsy. A final median score was listed for comparison of individual biopsies. For statistical analyses, the grouped median and range were calculated; comparisons between groups were made by non-parametric Wilcoxon tests. For multivariate analyses, binary logistic regression was performed for low CD4 infiltrates (score 0 versus scores 1–3) and low neutrophil infiltrates (score 0 versus scores 1–2).

Ethical considerations

All patients gave written informed consent to perform additional biopsies for research use. The protocol was approved by the local ethical committee at the University of Regensburg Medical Centre.

Results

Comparison of biopsies obtained after allogeneic SCT and controls

In contrast to controls, as expected, post-transplant biopsies showed an increase in epithelial apoptosis and a loss of crypts. Eosinophils and neutrophils were more prominent in post-transplant biopsies. There was a trend for an increased CD8 infiltrate, whereas both CD4 and FoxP3+ cells were reduced significantly following SCT. Lamina propria macrophages seemed to be less affected (Table 2). When we analysed the correlation of apoptosis with cellular infiltrates, there was a strong association between CD8 cells in the lamina propria and apoptosis (r = 0·78, P = 0·002), suggesting that cytotoxic T cells might be the major effector cells of intestinal damage. Epithelial proliferation as indicated by MIB1 staining was increased following SCT and might reflect compensatory epithelial repair. The six patients analysed prior to SCT showed intermediate changes with minor cellular infiltrates and absence of apoptosis (data not shown).

Table 2.

Comparison of (immuno-)histological changes in controls and patients after allogeneic stem cell transplantation (SCT).

| Control (n = 12) | Patients after SCT (n = 58) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptotic nuclei | 0·1 (1) | 0·8 (3) | 0·03 |

| Loss of crypts | 0 (0) | 1·0 (3) | 0·05 |

| Eosinophils LP | 0·2 (2) | 0·7 (3) | 0·02 |

| Neutrophils LP | 0 (1) | 0·4 (2) | 0·08 |

| CD4 LP | 1·7 (1) | 0·8 (3) | 0·00 |

| FoxP3 positive cells LP | 1·1 (2) | 0·5 (2) | 0·02 |

| CD8 LP | 1·0 (0) | 1·4 (3) | 0·06 |

| MIB1 | 1·1 (1) | 1·6 (3) | 0·05 |

| CD68 LP | 1·3 (1) | 1·4 (1) | Ns |

Median (immune-)histological changes and ranges are given. Wilcoxon texts were performed to define significant changes. Forkhead box P3 (FoxP3): marker of regulatory T cells; MIB 1: epithelial proliferation; CD68: macrophage marker; LP: lamina propria.

Loss of CD4 cells and neutrophils in severe GVHD

Only four patients had no evidence of GVHD in histology and recovered clinically; 32 had stages 1 and 2; and 22 stages 3 and 4 intestinal GVHD, confirmed by histology in all patients. To assess the impact of GVHD severity on histological changes, patients were grouped according to the clinical severity of intestinal GVHD (stages 0–2 versus stages 3 and 4) at the time of biopsy (Table 3). Patients with severe GVHD had the lowest CD4- and neutrophil infiltrates, whereas the highest CD4 score was observed in the few patients without and those with stage 1 GVHD: median CD4 infiltrates were scored 1·1 (range 3) in patients with GVHD 0–2 and dropped to a score of 0·4 (range 1) in patients with severe GVHD (P < 0·002). Median CD4 density in the few patients without GVHD was scored 1·3 (range 2), confirming the stage-dependent loss of CD4 cells (data not shown). Similar changes were seen for the neutrophil infiltrate, whereas all other parameters showed only trends (e.g. for a further increase of CD8 cells or a decrease of FoxP3 cells). To assess further the role of FoxP3+ cells, we calculated the FoxP3/CD4 and FoxP3/CD8 ratio in all post-transplant biopsies. Whereas there was no difference for FoxP3/CD4 ratio between patients with mild and severe GVHD, the FoxP3/CD8 ratio decreased from 0·8 [standard error (s.e.) 0·2] in mild to 0·4 (s.e. 0·1) in more severe GVHD with borderline significance (P = 0·05).

Table 3.

Severity of clinical gastrointestinal (GI) graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) at the time of biopsy and (immuno)histological changes.

| GI-GVHD 0–2 (n = 17) | GI-GVHD 3–4 (n = 41) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Apoptotic nuclei | 0·5 (3) | 0·9 (2) | Ns |

| Loss of crypts | 0·9 (3) | 1·3 (2) | Ns |

| Eosinophils LP | 0·7 (2) | 0·5 (2) | Ns |

| Neutrophils LP | 0·4 (2) | 0·05 (1) | 0·01 |

| CD4 LP | 1·1 (3) | 0·4 (1) | 0·002 |

| FoxP3 positive cells LP | 0·5 (2) | 0·3 (1) | Ns |

| CD8 LP | 1·2 (2) | 1·6 (3) | Ns |

| MIB1 | 1·4 (2) | 1·7 (3) | Ns |

| CD68 LP | 1·4 (1) | 1·3 (1) | Ns |

Median (immune-)histological changes and ranges are given. Wilcoxon texts were performed to define significant changes. Forkhead box P3 (FoxP3): marker of regulatory T cells; MIB 1: epithelial proliferation; CD68: macrophage marker; LP: lamina propria.

Factors affecting CD4 and neutrophil infiltrates

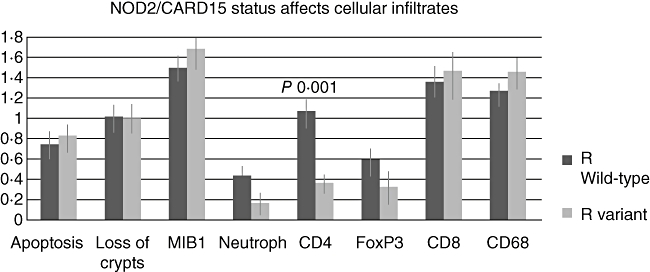

As patients were at different phases of their clinical GVHD and under different intensities of immunosuppressive treatment, we next checked whether confounding treatment or patient parameters had an impact on the observed changes in CD4 and neutrophil counts. In addition, we addressed the hypothesis that the NOD2/CARD15 status could affect the histological and pathophysiological manifestation of GVHD. Among pretransplant factors, neither the type of donor, the intensity of conditioning, age or underlying disease had any impact on CD4 and neutrophil infiltrates. Surprisingly, the recipient NOD2/CARD15 status had a dramatic impact on CD4 cells, as the CD4 score dropped from a median of 1·1 (3) in patients with wild-type NOD2/CARD15 to a score of 0·4 (1) in patients with presence of variants (P 0·002) (Fig. 1). This decline in CD4 cells was seen in both subgroups: patients with mild and patients with severe gastrointestinal (GI-)GVHD (Table 4). A similar but not significant trend was seen for the neutrophil counts. In contrast, donor NOD2/CARD15 status had a stronger influence on neutrophil infiltrates: neutrophil density was 0·5 (1) in wild-type donors but only 0·0 (1) in donors with NOD2/CARD15 variants (P < 0·05, data not shown). There was no significant impact of donor NOD2/CARD15 status on CD4 cell infiltrates.

Fig. 1.

Recipient nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2/caspase recruitment domain 15 (NOD2/CARD15) status affects CD4 infiltrates. Biopsies obtained post-transplant were grouped according to absence (wild-type) or presence (variant) of any NOD2/CARD15 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Median (immune-)histological changes (±standard error) are shown. Wilcoxon tests were performed to define significant changes. LP: lamina propria; forkhead box P3 (FoxP3): marker of regulatory T cells; MIB 1: epithelial proliferation; CD68: macrophage marker.

Table 4.

Recipient (R) nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2/caspase recruitment domain 15 (NOD2/CARD15) status affects median CD4 infiltrate independent from severity of graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).

| R wild-type (n = 40) | R variant (n = 19) | |

|---|---|---|

| GI-GVHD 0–2 (n = 17) | 1·27 (0·2), n = 14 | 0·50 (0·2), n = 3 |

| GI-GVHD 3/4 (n = 41) | 0·57 (0·1), n = 25 | 0·27 (0·1), n = 16 |

Variant: presence of any NOD2/CARD15 SNP. Median CD4 infiltrates (±standard error) are shown. Recipient NOD2/CARD15 status was the only significant factor affecting CD4 infiltrate in multivariate logistic regression analysis. GI: gastrointestinal.

Among the post-transplant factors, use of corticosteroids resulted in a significant suppression of CD4 cells and a marginal reduction of neutrophils: median CD4 density was 1·0 (2) in patients with low dose or without steroids, while it dropped to 0·5 (1) in patients with high-dose steroids (exceeding 1 mg/kg prednisolone) (P < 0·02). Neutrophil density was lower in patients with high-dose steroids [score 0·4 (1)]versus score 0·8 (1) in patients with low-dose steroids (P < 0·04). In addition, CD4 cells were influenced by the additional use of T cell antibodies or etanercept (data not shown). Concomitant viral infections with a low number of copies were detected in 11 patients (CMV n = 4, HHV6 n = 7), but histology indicated viral disease in none of the biopsies as the leading cause of gastrointestinal damage. In addition, presence of viruses was distributed equally among patients with mild (36%) and patients with severe GVHD (43%), and presence of viruses did not affect immunohistological features of biopsies.

As NOD2/CARD15 had been shown to affect the severity of GVHD, and the use of high-dose steroids as well as antibodies also reflect the extent of clinical GVHD at the time of biopsy, a multivariate analysis was performed addressing these factors. For low neutrophil density, none of the factors remained significant. For CD4 density, however, the recipient NOD2/CARD15 status remained the only highly significant factor, with an odds ratio of 0·02 for patients without NOD2/CARD15 variants (95% confidence interval: 0·01–0·32, P < 0·002).

Discussion

Our study revealed both confirmatory and new aspects of immunohistopathological changes of gastrointestinal GVHD.

As reported in several studies [13–15], severe acute GVHD was accompanied by an increase in apoptotic epithelial cells which correlated with cytotoxic CD8 T cell infiltrates. By adding a marker of epithelial proliferation, we were able to demonstrate a compensatory attempt of epithelial repair. As published previously by some groups, CD4 infiltrates were even more reduced in severe GVHD, resulting in a shift of the CD4/CD8 ratio towards CD8 [15–17]. Staining for FoxP3, a marker of regulatory T cells, revealed a parallel decrease of FoxP3 cells after SCT which seemed to be more pronounced in severe GVHD; indeed, the FoxP3/CD8 ratio was significantly lower in patients with severe GVHD. Thus, our findings are in line with a recent observation of Rieger and co-workers [18]. However, the overall loss of CD4+ T cells was even more pronounced than that of the FoxP3+ subpopulation, suggesting that a preferential loss of FoxP3+ cells does not account solely for the occurrence of GVHD. As we did not perform double staining in this pilot study, this discrepancy may also be explained by further FoxP3+ cells beyond CD4 cells such as FoxP3+ CD8 cells, which have been reported both in experimental models and in biopsies from organ transplant recipients [19,20].

A second finding not reported in previous studies was suppression of neutrophil infiltrates in severe GVHD. As our biopsies were not obtained at identical time-points in relation to the initiation of GVHD treatment, actual immunosuppressive treatment might result in indirect effects, and this was clearly confirmed for high-dose corticosteroid treatment and the use of monoclonal agents.

An unexpected and initially surprising observation was the clear impact of NOD2/CARD15 SNPs on the cellular infiltrate: donor NOD2/CARD15 status affected the neutrophil infiltrate, but this was not significant in multivariate analysis. Neutrophil recruitment is the main effect of the chemokine interleukin (IL)-8, which is a typical cytokine induced by a NOD2/CARD15-dependent activation of nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) and is used in many studies as a functional readout for intact NOD2/CARD15 signalling [9].

Recipient NOD2/CARD15 status was associated with a severe reduction of CD4 cells, which was observed independently from the severity of GVHD, and remained the only significant factor in the multivariate analysis. Interestingly, similar results are found in an ongoing study on skin biopsies, suggesting that the interaction of NOD2/CARD15 and CD4 might be a general biological phenomenon in epithelial tissues. Although these findings need confirmation in a prospective trial with a more homogeneous population of untreated GVHD, there are several recent data supporting that NOD2/CARD15 might be involved in the recruitment of CD4 cells in epithelial tissues. An important population in intestinal inflammation is the T helper type 17 (Th17) cells, which have been shown to have either detrimental or protective effects in different animal models of GVHD [21–23]. So far, human data on Th17 cells in intestinal GVHD are missing. Interestingly, APCs seem to produce IL-23 and induce Th17 in a NOD2/CARD15-dependent manner [24], and therefore different recruitment of Th17 cells might play a role. A further chemokine involved in APC recruitment of memory T cells is MIP3alpha, which is also produced under the control of NOD2/CARD15 (G. Rogler, unpublished data). Thus, recruitment of antigen-specific memory cells involved in anti-bacterial defence against commensal bacteria might be disturbed in the presence of NOD2/CARD15 SNPs. A direct link between regulatory T cells and NOD2/CARD15 has not been reported so far. Ongoing studies to attempt to clarify whether epithelial factors (thymic stromal lymphopoetin, TSLP; [25]) or APC factors (such as retinoid acid, [26]) involved in recruitment of regulatory T cells are produced in a NOD2/CARD15-dependent manner. The exact contribution of regulatory T cells, memory cells and Th17 cells to the observed decrease of CD4 cells is now being analysed in ongoing projects. A major role of NOD2/CARD15 in APCs rather than epithelial cells in the setting of GVHD is also suggested by the recently published study on NOD2/CARD15 knock-out mice, where only the defect in host haematopiesis-derived cells (including APCs) accelerated GVHD [27].

Our findings clearly need confirmation in a larger study including biopsies prior to initiation of immunosuppressive treatment of GVHD in order to exclude indirect effects of concomitant medication. However, they point to two important aspects: first, the significant loss of CD4 in more severe GVHD suggests that intestinal CD4 cells play an important role in immunological homeostasis preventing uncontrolled inflammation against intestinal bacteria. In GVHD, pathophysiological interactions initiating a pathological immune response might be similar to inflammatory bowel disease, whereas the effector phase with damage by alloreactive T cells is clearly different.

Finally, our current immunosuppressive strategies deplete T cell populations somewhat unselectively and therefore might even worsen the loss of immunomodulatory CD4 T cell populations. This observation might explain why, so far, any type of second-line treatment of GVHD results in equally unsatisfactory results, with only approximately 30% of patients becoming long-term survivors. In addition, the link between NOD2/CARD15 SNPs and intestinal CD4 infiltrates provides direct evidence for the relevance of innate immune mechanisms for the recruitment of specific and adaptive effector cells. A more precise insight in the interaction of Toll-like (TLR) and NOD-like (NLR) receptors, activation of APCs and subsequent recruitment of T cell subpopulations might open more selective or even organ-specific strategies to manipulate GVHD in the future.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the nurses and technicians involved in the collection and preparation of samples, especially D. Gaag, for performing all the histological and immunohistological stainings. We thank our patients for giving their informed consent to additional biopsies. The authors acknowledge support of a grant from the Wilhelm-Sander Foundation.

Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no potential conflicts of interest related to the contents of the publication.

References

- 1.Baumgart DC, Carding SR. Inflammatory bowel disease: cause and immunobiology. Lancet. 2007;369:1627–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60750-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rogler G. Update in inflammatory bowel disease pathogenesis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2004;20:311–17. doi: 10.1097/00001574-200407000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Bekkum DW, Roodenburg J, Heidt PJ, van der WD. Mitigation of secondary disease of allogeneic mouse radiation chimeras by modification of the intestinal microflora. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1974;52:401–4. doi: 10.1093/jnci/52.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chakraverty R, Cote D, Buchli J, et al. An inflammatory checkpoint regulates recruitment of graft-versus-host reactive T cells to peripheral tissues. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2021–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gerbitz A, Schultz M, Wilke A, et al. Probiotic effects on experimental graft-versus-host disease: let them eat yogurt. Blood. 2004;103:4365–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-11-3769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Holler E, Rogler G, Brenmoehl J, et al. Prognostic significance of NOD2/CARD15 variants in HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: effect on long-term outcome is confirmed in 2 independent cohorts and may be modulated by the type of gastrointestinal decontamination. Blood. 2006;107:4189–93. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holler E, Rogler G, Herfarth H, et al. Both donor and recipient NOD2/CARD15 mutations associate with transplant-related mortality and GvHD following allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2004;104:889–94. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-10-3543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hildebrandt GC, Granell M, Urbano-Ispizua A, et al. Recipient NOD2/CARD15 variants: a novel independent risk factor for the development of bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2008;14:67–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Heel DA, Hunt KA, King K, et al. Detection of muramyl dipeptide-sensing pathway defects in patients with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12:598–605. doi: 10.1097/01.ibd.0000225344.21979.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zelinkova Z, van Beelen AJ, de Kort F, et al. Muramyl dipeptide-induced differential gene expression in NOD2 mutant and wild-type Crohn's disease patient-derived dendritic cells. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:186–94. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogura Y, Bonen DK, Inohara N, et al. A frameshift mutation in NOD2 associated with susceptibility to Crohn's disease. Nature. 2001;411:603–6. doi: 10.1038/35079114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wehkamp J, Harder J, Weichenthal M, et al. NOD2 (CARD15) mutations in Crohn's disease are associated with diminished mucosal alpha-defensin expression. Gut. 2004;53:1658–64. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.032805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bombi JA, Nadal A, Carreras E, et al. Assessment of histopathologic changes in the colonic biopsy in acute graft-versus-host disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995;103:690–5. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/103.6.690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sale GE, Shulman HM, McDonald GB, Thomas ED. Gastrointestinal graft-versus-host disease in man. A clinicopathologic study of the rectal biopsy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1979;3:291–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-197908000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shidham VB, Chang CC, Shidham G, et al. Colon biopsies for evaluation of acute graft-versus-host disease (A-GVHD) in allogeneic bone marrow transplant patients. BMC Gastroenterol. 2003;3:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-3-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sviland L, Pearson AD, Green MA, et al. Immunopathology of early graft-versus-host disease – a prospective study of skin, rectum, and peripheral blood in allogeneic and autologous bone marrow transplant recipients. Transplantation. 1991;52:1029–36. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199112000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weisdorf SA, Roy J, Snover D, Platt JL, Weisdorf DJ. Inflammatory cells in graft-versus-host disease on the rectum: immunopathologic analysis. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1991;7:297–301. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rieger K, Loddenkemper C, Maul J, et al. Mucosal FOXP3+ regulatory T Cells are numerically deficient in acute and chronic GvHD. Blood. 2006;107:1717–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-06-2529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wong J, Obst R, Correia-Neves M, Losyev G, Mathis D, Benoist C. Adaptation of TCR repertoires to self-peptides in regulatory and nonregulatory CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:7032–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou H, Wang ZD, Zhu X, You Y, Zou P. CD8+FOXP3+T cells from renal transplant recipients in quiescence induce immunoglobulin-like transcripts-3 and -4 on dendritic cells from their respective donors. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:3065–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2007.02.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlson MJ, West ML, Coghill JM, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, Blazar BR, Serody JS. In vitro differentiated TH17 cells mediate lethal acute graft-versus-host disease with severe cutaneous and pulmonary pathology. Blood. 2009;113:1365–74. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-06-162420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kappel LW, Goldberg GL, King CG, et al. IL-17 contributes to CD4-mediated graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2009;113:945–52. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yi T, Zhao D, Lin CL, et al. Absence of donor Th17 leads to augmented Th1 differentiation and exacerbated acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2008;112:2101–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-126987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Beelen AJ, Zelinkova Z, Taanman-Kueter EW, et al. Stimulation of the intracellular bacterial sensor NOD2 programs dendritic cells to promote interleukin-17 production in human memory T cells. Immunity. 2007;27:660–9. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu YJ. TSLP in epithelial cell and dendritic cell cross talk. Adv Immunol. 2009;101:1–25. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2776(08)01001-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Cárcamo CV, et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1757–64. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Penack O, Smith OM, Cunningham-Bussel A, et al. NOD2 regulates hematopoietic cell function during graft-versus-host disease. J Exp Med. 2009;206:2101–10. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]