Abstract

Background

Retinoblastoma, a curable eye tumor, is associated with poor survival in Central America (CA). To develop a retinoblastoma program in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, twinning initiatives were undertaken between local pediatric oncology centers, nonprofit foundations, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, and the University of Tennessee Hamilton Eye Institute.

Procedure

The retinoblastoma program focused on developing early diagnosis programs in Honduras with national vaccination campaigns, developing treatment protocols suited to local conditions, building local networks of oncologists and ophthalmologists, training local healthcare providers, using modern donated equipment for diagnosis and treatment, and the ORBIS Cybersight consultation program and Internet meetings to further education and share expertise. Pediatric ophthalmologists and oncologists worked with foundations to treat patients locally with donated equipment and Internet consultations, or at the center in Guatemala.

Results

Number of patients successfully treated increased after the program was introduced. For 2000–2003 and 2004–2007, patients abandoning/refusing treatment decreased in Guatemala from 20 of 95 (21%) to 14 of 123 (11%) and in Honduras from 13 of 37 (35%) to 7 of 37 (19%). Survival in El Salvador was good and abandonment/refusal low for both periods. Of 18 patients receiving focal therapy for advanced disease, 14 have single remaining eyes.

Conclusion

Development of the program in CA has decreased abandonment/refusal and enabled ophthalmologists at local centers to use modern equipment to provide better treatment. This approach might serve as a guide for developing other multispecialty programs.

Keywords: Retinoblastoma, pediatric oncology, treatment, developing countries, RetCam

INTRODUCTION

Retinoblastoma is a rare pediatric eye tumor with cure rates of more than 90% in developed countries.1 Unfortunately, in countries with limited resources, cure rates for retinoblastoma are less than 50%, and significant morbidity is often seen in survivors.2 We have previously reported the development of pediatric oncology programs in Central America (CA), which have resulted in improvements in survival rates of children with acute lymphocytic leukemia and other pediatric tumors.3 In El Salvador, for example, the survival rate of children with acute lymphocytic leukemia increased from an estimated 10% to approximately 60% between 1994 and 1996 after the development of a twinning program.4 We have also recently reported the development of a retinoblastoma program in Jordan.5 In a related effort, twinning programs were developed in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras between local pediatric oncology centers, their supporting nonprofit foundations, the International Outreach Program at the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital (St. Jude), and the ocular oncology team at the University of Tennessee Hamilton Eye Institute (UTHEI).

We report here the development of programs to diagnose and treat retinoblastoma at these oncology centers. Members of the retinoblastoma team at St. Jude and UTHEI, in conjunction with local non-profit foundations, helped create a network of oncologists and ophthalmologists in these countries, develop treatment protocols suited to local conditions, promote early diagnosis, improve treatment at local treatment centers, increase awareness by sponsoring ophthalmologists to attend conferences, and provide training locally as well as at St. Jude. Essential equipment and services were donated by the nonprofit humanitarian organization ORBIS, Clarity Medical Systems, and individual donors and a real-time online consultation was developed by physicians at St. Jude and UTHEI partnering with ORBIS.

METHODS

An initial review of retinoblastoma treatment and feedback from the pediatric oncology centers showed that increasing awareness of the disease, which in turn would lead to early diagnosis, and improving therapy were chief concerns. Program development took advantage of local strengths and opportunities. An early diagnosis program was developed in Honduras by partnering with the government-sponsored immunization program and educating primary care providers. In Guatemala, in addition to developing early diagnosis programs and educating healthcare providers, a satellite ophthalmology clinic as well as a referral center staffed by a US-trained pediatric ophthalmologist with expertise in retinoblastoma were set up. The retinoblastoma treatment team at St. Jude and the UTHEI (both in Memphis, TN) collaborated to develop a network of ophthalmologists and pediatric oncologists in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Existing pediatric oncology centers and their supporting non-profit foundations served as a starting point in these countries, ensuring that retinoblastoma patients had access to well-established psychosocial and financial support.6

A major step in improving treatment and outcome was to develop a treatment protocol for retinoblastoma in CA appropriate for local conditions and resources. In 1999, the Association of Central American Pediatric Hematologists/Oncologists (AHOPCA) developed a therapeutic multidisciplinary protocol comprising chemotherapy, surgery, and radiation therapy for children with retinoblastoma.7 By 2000, this protocol was being used in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua for most retinoblastoma patients. A new protocol has been recently developed on the basis of results of the initial protocol. This protocol uses the RetCam and communication infrastructure (computers and Internet access) developed in the centers and incorporates real-time meetings of pediatric oncologists and ophthalmologists by using the conferencing feature of www.cure4kids.org, an educational Web site developed by St. Jude, to discuss all new cases. As of now, we do not find it appropriate to post this relatively new protocol that uses Internet conferencing because health care providers who are not familiar with all aspects of the protocol run the risk of using this protocol inappropriately to treat patients.

A consultation service was developed for the 3 countries in 2004 by partnering with ORBIS (a nonprofit humanitarian organization devoted to blindness prevention and treatment in developing countries; www.orbis.org), using the ORBIS CyberSight online network. This program features E-Consultation, which facilitates communication and mentorship between health care workers in developing countries and specialists in state-of-the-art centers in developed countries. The E-Consultation program allows sharing clinical information, including images, with experts on specific eye diseases. Once a partner submits a case file, an expert is notified by e-mail and reviews the case and provides immediate advice. The file can remain open for additional communication between the partner and mentor. This system has been used to review and provide consultation for care and treatment of individual patients with retinoblastoma. Consultations are performed by an ophthalmologist (MWW) and pediatric oncologist (CR-G). RetCam photos make it possible to make specific treatment recommendations for patients with complicated or bilateral disease.

The International Outreach Program at St. Jude sponsored several ophthalmologists from CA who worked most closely with the local centers to attend the yearly meetings of the Panamanian Ophthalmology Society in August 2003, October 2005, and September 2006. These meetings were ideal for the ophthalmologists to attend as they were in Spanish, were of interest to general ophthalmologists, and were held in the region. At the meetings, a separate retinoblastoma group met to discuss problems related to treatment of retinoblastoma and the development of a program. Attendance at these meetings was also supported and facilitated by the Panamanian Ophthalmology Society.

Pediatric oncologists and ophthalmologists were also invited to the St. Jude retinoblastoma conferences in 2005 and 2007.9 Ophthalmologists from CA attended 2- to 4-week rotations to see how retinoblastoma patients are treated and become familiar with the RetCam and the functioning of a multidisciplinary retinoblastoma team. Ophthalmologists and bilingual technicians (BGH, MWW, BP) from St. Jude and UTHEI made site visits and training trips to Guatemala, Honduras, and Panama.

Equipment was donated to the treatment centers in Guatemala and Honduras, including RetCam (Clarity Medical Systems, Pleasanton, CA), diode laser, ultrasound, and cryotherapy units. Prostheses and implants were donated by a grant of $3000/year by the St. Jude Volunteer Auxiliary. Apart from the donations of equipment, the overall cost of developing and operating the program to date (travel, equipment maintenance, salary) is approximately US$30,000 per year.

RESULTS

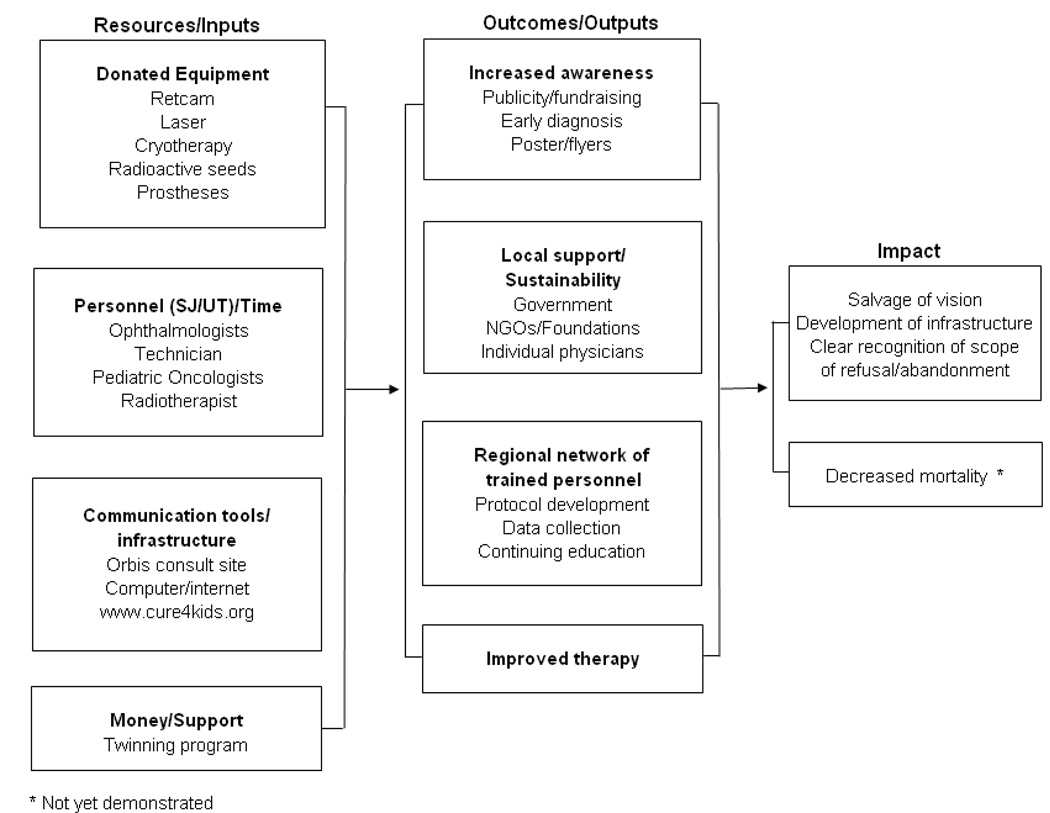

Table I shows an impact evaluation for the program. Specific examples of outcomes are listed below.

Table I.

Impact Evaluation

|

EARLY DIAGNOSIS

Results of an early diagnosis program started in Honduras in conjunction with a national vaccination campaign in 2003 and being continued yearly have been previously reported.8 The relatively inexpensive program has been effective in promoting earlier diagnosis of retinoblastoma: there has been an increase in the number of referrals and, more importantly, a significant decrease (from 73% to 35%) in the occurrence of extraocular disease. Also, an ophthalmology clinic has been recently established in an indigenous town in Guatemala, about 50 miles from Guatemala City, and a program been initiated to teach students at the medical school and the midwife training program to detect the early signs and symptoms of retinoblastoma.

TRAINING AND EDUCATION

A well-trained pediatric ophthalmologist interested in treating retinoblastoma in Guatemala was provided incentive pay to be in charge of the program to help treat patients, assist other ophthalmologists from CA, and develop the program in Guatemala so that it could serve as a referral center. One pediatric oncologist was appointed to coordinate treatment with the ophthalmologist. As improvements were made and treatments became more sophisticated, a brachytherapy program was developed in Guatemala. This is the only ocular brachytherapy program in CA, developed through the help and support of the Radiation Oncology Division at St. Jude and a local radiotherapist. An ophthalmologist (MWW) supervised the placement of seeds in the first 2 patients in Guatemala. There has been cooperation among the countries with patient referrals to the brachytherapy program in Guatemala for evaluation of complex cases and for procedures not available locally (e.g., RetCam fundus photography, placement of I-125 episcleral plaques) in an effort to save vision in complex cases, particularly in patients with bilateral disease. The Guatemala center has thus far treated 10 eyes with brachytherapy, including patients from El Salvador, Honduras, and Mexico.

Biweekly multidisciplinary real-time conferences are conducted to discuss retinoblastoma patients with advanced or complicated disease via the St. Jude educational Web site www.cure4kids.org. Live conferences and the ORBIS E-consultation system have been used to discuss more than 300 consults. Also, presentations from the 2007 Retinoblastoma: One World, One Vision symposium held at St. Jude are available on the Web site.

Patient Information

Patient and survival data have been entered into the Pediatric Oncology Networked Database (POND; www.pond4kids.org).10 Table II shows the number of patients who are alive; have expired, abandoned, or refused therapy; or have been lost to follow-up in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras during 2000–2003 and 2004–2008. In contrast to El Salvador, where most patients had low-stage disease and survival rates were consistently very high (28 of 35 [80%] for 2000–2003; 30 of 36 [83%] for 2004–2008), most patients in Guatemala and Honduras had advanced disease. The median age of patients at diagnosis in the 2 time periods was approximately 2.4 years, and did not differ significantly by country or time period. There was no statistically significant difference in survival between the 2 periods. Abandonment (generally defined as failure to return for treatment for 8 or more weeks) and refusal rates were significantly lower during 2004–2008 (21% vs. 11%, P = 0.014)

Table II.

Status of Retinoblastoma Patients

| El Salvador | Guatemala | Honduras | All Patients | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 – 2003 | ||||

| Alive | 28 (80%) | 28 (29%) | 12 (32%) | 68 (40%) |

| Expired | 3 (9%) | 30 (32%) | 9 (24%) | 42 (25%) |

| Abandoned / Refused | 2 (6%) | 20 (21%) | 13 (35%) | 35 (21%) |

| Lost to F/U | 2 (6%) | 17 (18%) | 3 (8%) | 22 (13%) |

| Total | 35 | 95 | 37 | 167 |

| 2004–2008 | ||||

| Alive | 30 (83%) | 69 (56%) | 21 (56%) | 120 (61%) |

| Expired | 4 (11%) | 38 (31%) | 9 (24%) | 51 (26%) |

| Abandoned / Refused | 1 (3%) | 14 (11%) | 7 (19%) | 22 (11%) |

| Lost to F/U | 1 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (2%) |

| Total | 36 | 123 | 37 | 196 |

Since the donation of the RetCam in Guatemala, the number of patients and examinations under anesthesia has increased. For 147 patients, the number of examinations was 132 in 2004, 208 in 2005, 304 in 2006, and 281 in 2007. There are currently 18 patients receiving focal treatment for advanced disease, 14 of whom are receiving treatment in a single remaining eye that would have to be enucleated prior to the advent of this program. Increase in the number of examinations after introduction of the RetCam reflects the increased availability of focal therapy and decreased number of enucleations.

DISCUSSION

The treatment for retinoblastoma is complex. Although cancer cure remains a priority, eye salvage and vision preservation are equally important. A program to treat patients with retinoblastoma in CA has been developed in El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras through the cooperation of local pediatric oncology centers, their supporting non-profit foundations, the International Outreach Program at St. Jude, the retinoblastoma team at UTHEI, and ORBIS. When the programs began, early diagnosis and referral to a trained practitioner were priorities. As the programs grew, the need to provide more sophisticated ocular salvage necessitated more input and resources. There is now a network of pediatric oncologists and ophthalmologists who have the knowledge to diagnose and treat retinoblastoma. Also, ophthalmologists can now work together at the pediatric oncology centers using modern equipment such as RetCams, which facilitate rapid consultation, and diode lasers and cryotherapy units, which allow focal treatment of intraocular disease in an effort to avoid external beam radiotherapy or enucleation. A concurrent program in Jordan, results of which have been recently reported, uses similar methods of multidisciplinary team development, acquisition of equipment, and telemedicine consultations to improve eye salvage.5

Treatment is provided at already established pediatric oncology centers that are supported by local non-profit foundations that provide some social services and financial help for families6. This support is crucial to decrease the high rates of abandonment and refusal of therapy that occur among patients with retinoblastoma and their and families in countries with limited resources. Experts also provide consultation via collaborative online networks to ensure optimal therapy to patients with complicated disease. These consultations have also improved local expertise.

We found no statistically significant increase in rates of survival for patients with retinoblastoma for 2000–2003 and 2004–2008. This probably reflects the low number of patients after censoring for abandonment in the early period. Except for El Salvador, significantly fewer patients refused initial therapy or abandoned treatment over the most recent period, and we expect this decrease to ultimately contribute to increased rates of survival with continued follow-up. Late diagnosis resulting in advanced disease11 and abandonment of therapy continue to be major factors contributing to decreased survival. These problems are more social than medical; therefore, future efforts to improve survival for patients with retinoblastoma in these countries need to focus on more than medical issues (i.e., programs of awareness, identification of early signs by caregivers, supportive measures to decrease abandonment of therapy) while maintaining present infrastructures.

The program in El Salvador has been the most successful in terms of early diagnosis and reduced abandonment, perhaps due in part to the small size of the country, which decreases travel time, and the relative homogeneity of the population. Ongoing donation of prostheses, an important supportive measure, will not only improve cosmetic results but will hopefully also decrease both abandonment and refusal rates as parents are assured that children with enucleations can look normal. Parent groups can also provide emotional and educational support for new families. Improved data collection, including cost analysis, is necessary to develop cost-effective programs.

Technology, including case consultations on the Cure4Kids and ORBIS Web sites as well as development of training modules for RetCam, can provide both expert advice on individual cases and cost-effective education in low-income countries. Although our informal experience has shown that online education is cheaper than traveling in person to provide education, no formal comparative analysis has been done regarding this. The online case consultations have helped decrease morbidity by salvaging eyes that previously could be treated only by enucleation The ultimate goal of the program is to develop self-sufficient programs capable of giving care equivalent to that in developed countries. Such care consists of at least 90% survival, good cosmetic results, and salvage of vision when possible through local measures and brachytherapy . Although the system is still fragile, several components of sustainability are in place including equipment, trained physicians, data collection methods, foundation, and government support. Continuing to increase awareness by training ophthalmologists, promoting early diagnosis of disease, and receiving expert advice via real-time online networking will be essential to guarantee the long-term success of the initiative in CA. Purchase of contracts for maintaining equipment in the 3 countries has been added to the budget of the twinning program. Data collection is crucial for sustainability of outcome measures and demonstrating success or failure to donors and the government.

Another benefit of the program is the possibility of local ophthalmologists collaborating with investigators at St. Jude and other groups to analyze fresh retinoblastoma tissue samples and designing treatment protocols for patients with advanced disease, neither of which can be easily accomplished in developing countries.

Developing the program has been a learning experience. Initially, it was difficult to arrange to process donations of equipment, particularly the RetCam, through customs, to find appropriate locations to house the equipment and to keep it functioning. These problems were solved through help from the local foundations and technical support from Clarity Medical Systems. As is known to occur with other Internet exchanges, initial face-to-face meetings between participants facilitated online interactions. Early diagnosis campaigns have progressed more slowly in Guatemala compared to Honduras, but discussions regarding various approaches among pediatric oncologists and ophthalmologists have resulted in modifying successful programs for local conditions.

We used the pediatric oncology center as the focal point for program development, but progress was possible only because of the commitment of ophthalmologists. Similar programs to improve outcomes of retinoblastoma and brain tumors or other diseases can be developed by collaborative efforts of multidisciplinary teams using the strongest, most developed specialty as a focal point.

Acknowledgment

We thank Donald Samulack, PhD, and Vani Shanker, PhD, of the Department of Scientific Editing at the St. Jude Children's Research Hospital for editorial assistance and Catherine Billups, MS, from the Department of Biostatistics for statistical analysis.

This work was supported in part by grant CA21765 from the National Institutes of Health and by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC).

REFERENCES

- 1.Hurwitz RL, Shields CL, Shields JA, et al. Retinoblastoma. In: Pizzo PA, Poplack DG, editors. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2006. pp. 865–886. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leal-Leal CA, Rivera-Luna R, Flores-Rojo M, et al. Survival in extra-orbital metastatic retinoblastoma: treatment results. Clin Transl Oncol. 2006;8:39–44. doi: 10.1007/s12094-006-0093-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonilla M, Moreno N, Marina N, et al. Acute lymphoblastic leukemia in a developing country: preliminary results of a nonrandomized clinical trial in El Salvador. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2000;22:495–501. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200011000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wilimas JA, Ribeiro RC. Pediatric hematology-oncology outreach for developing countries. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2001;15:775–787. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qaddoumi I, Nawaiseh I, Mehyar M, et al. Team management, twinning, and telemedicine in retinoblastoma: A 3-tier approach implemented in the first eye salvage program in Jordan. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;51:241–244. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sala A, Barr RD, Masera G the MISPHO Consortium. A Survey of Resources and Activities in the MISPHO Family of Institutions in Latin America: A Comparison of Two Eras. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2004;43:758–764. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Howard SC, Ortiz R, Baez LF, et al. Protocol-based treatment for children with cancer in low income countries in Latin America: a report on the recent meetings of the Monza International School of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology (MISPHO) – part II. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:486–490. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leander C, Fu FC, Peña A, et al. Impact of an education program on late diagnosis of retinoblastoma in Honduras. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:817–819. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez-Galindo C, Wilson MW, Chantada G, et al. Retinoblastoma: One World, One Vision. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e763–e770. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayoub L, Fu L, Peña A, et al. Implementation of a data management program in a pediatric cancer unit in a low income country. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;49:23–27. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chantada G, Fandiño A, Manzitti J, Urrutia L, Schvartzman E. Late diagnosis of retinoblastoma in a developing country. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80:171–174. doi: 10.1136/adc.80.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]