Abstract

Calonectria (Ca.) species and their Cylindrocladium (Cy.) anamorphs are well-known pathogens of forest nursery plants in subtropical and tropical areas of the world. An investigation of the mortality of rooted Pinus cuttings in a commercial forest nursery in Colombia led to the isolation of two Cylindrocladium anamorphs of Calonectria species. The aim of this study was to identify these species using DNA sequence data and morphological comparisons. Two species were identified, namely one undescribed species, and Cy. gracile, which is allocated to Calonectria as Ca. brassicae. The new species, Ca. brachiatica, resides in the Ca. brassicae species complex. Pathogenicity tests with Ca. brachiatica and Ca. brassicae showed that both are able to cause disease on Pinus maximinoi and P. tecunumanii. An emended key is provided to distinguish between Calonectria species with clavate vesicles and 1-septate macroconidia.

Keywords: β-tubulin, Calonectria, Cylindrocladium, histone, Pinus, root disease

INTRODUCTION

Species of Calonectria (anamorph Cylindrocladium) are plant pathogens associated with a large number of agronomic and forestry crops in temperate, subtropical and tropical climates, worldwide (Crous & Wingfield 1994, Crous 2002). Infection by these fungi gives rise to symptoms including cutting rot (Crous et al. 1991), damping-off (Sharma et al. 1984, Ferreira et al. 1995), leaf spot (Sharma et al. 1984, Ferreira et al. 1995, Crous et al. 1998), shoot blight (Crous et al. 1991, Crous et al. 1998), stem cankers (Sharma et al. 1984, Crous et al. 1991) and root disease (Mohanan & Sharma 1985, Crous et al. 1991) on various forest trees species.

The first report of Ca. morganii (as Cy. scoparium) infecting Pinus spp. was by Graves (1915), but he failed to re-induce disease symptoms and assumed that it was a saprobe. There have subsequently been several reports of Cylindrocladium spp. infecting Pinus and other conifers, leading to root rot, stem cankers and needle blight (Jackson 1938, Cox 1953, Thies & Patton 1970, Sobers & Alfieri 1972, Cordell & Skilling 1975, Darvas et al. 1978, Crous et al. 1991, Crous 2002). Most of these reports implicated Ca. morganii and Ca. pteridis (as Cy. macrosporum or Cy. pteridis) as the primary pathogens (Thies & Patton 1970, Ahmad & Ahmad 1982). However, as knowledge of these fungi has grown, together with refinement of their taxonomy applying DNA sequence comparisons (Crous et al. 2004, 2006), several additional Cylindrocladium spp. have been identified as causal agents of disease on different conifer species. These include Ca. acicola, Ca. colhounii, Ca. kyotensis (= Cy. floridanum), Ca. pteridis, Cy. canadense, Cy. curvisporum, Cy. gracile and Cy. pacificum (Hodges & May 1970, Crous 2002, Gadgill & Dick 2004, Taniguchi et al. 2008).

In a recent survey, wilting, collar and root rot symptoms were observed in Colombian nurseries generating Pinus spp. from cuttings. Isolations from these diseased plants consistently yielded Cylindrocladium anamorphs of Calonectria spp., and hence the aim of this study was to identify them, and to determine if they were the causal agents of the disease in Colombian nurseries.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Isolates

Pinus maximinoi and P. tecunumanii rooted cutting plants showing symptoms of collar and root rot (Fig. 1) were collected from a nursery close to Buga in Colombia. Isolations were made directly from lesions on the lower stems and roots on fusarium selective medium (FSM; Nelson et al. 1983) and malt extract agar (MEA, 2 % w/v; Biolab, Midrand, South Africa). After 5 d of incubation at 25 °C, fungal colonies of Calonectria spp. were transferred on to MEA and incubated further for 7 d. For each isolate, single conidial cultures were prepared on MEA, and representative strains are maintained in the culture collection (CMW) of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa and the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Fig. 1.

Collar and root rot on Pinus maximinoi and P. tecunumanii. a. Girdled stem of P. maximinoi; b. exposed P. maximinoi root collar showing discolouration and resin exudation; c, d. exposed P. tecunumanii root collars showing girdling and discolouration of the cambium.

Taxonomy

For morphological identification of Calonectria isolates, single conidial cultures were prepared on MEA and synthetic nutrient-poor agar (SNA; Nirenburg 1981). Inoculated plates were incubated at room temperature and examined after 7 d. Gross morphological characteristics were assessed by mounting fungal structures in lactic acid. Thirty measurements at ×1 000 magnification were made for each isolate. The 95 % confidence levels were determined for the pooled measurements of the respective species studied and extremes for structure sizes are given in parentheses. Optimal growth temperatures were determined between 6–36 °C at 6 °C intervals in the dark on MEA for each isolate. Colony reverse colours were determined after 7 d on MEA at 24 °C in the dark, using the colour charts of Rayner (1970) for comparison.

DNA phylogeny

Calonectria isolates were grown on MEA for 7 d. Mycelium was then scraped from the surfaces of the cultures, freeze-dried, and ground to a powder in liquid nitrogen, using a mortar and pestle. DNA was extracted from the powdered mycelium as described by Lombard et al. (2008). A fragment of the β-tubulin gene region was amplified and sequenced using primers T1 (O’Donnell & Cigelnik 1997) and CYLTUB1R (Crous et al. 2004) and a fragment for the histone H3 gene region was sequenced using primers CYLH3F and CYLH3R (Crous et al. 2004). The PCR reaction mixture used to amplify the different loci consisted of 2.5 units FastStart Taq polymerase (Roche Applied Science, USA), 10 × PCR buffer, 1–1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.25 mM of each dNTP, 0.5 μm of each primer and approximately 30 ng of fungal genomic DNA, made up to a total reaction volume of 25 μL with sterile distilled water.

Amplified fragments were purified using High Pure PCR Product Purification Kit (Roche, USA) and sequenced in both directions. For this purpose, the BigDye terminator sequencing kit (v3.1, Applied Biosystems, USA) and an ABI PRISMTM 3100 DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems) were used. All PCRs and sequencing reactions were performed on an Eppendorf Mastercycler Personal PCR (Eppendorf AG, Germany) with cycling conditions as described in Crous et al. (2006) for each locus. Sequences generated were added to other sequences obtained from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) and were assembled and aligned using Sequence Navigator v1.0.1 (Applied Biosystems) and MAFFT v5.11 (Katoh et al. 2005), respectively. The aligned sequences were then manually corrected where needed. PAUP (Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony, v4.0b10; Swofford 2002) was used to analyse the DNA sequence datasets. A partition homogeneity test (Farris et al. 1994) and a 70 % reciprocal bootstrap method (Mason-Gamer & Kellogg 1996) were applied to evaluate the feasibility of combining the datasets. Phylogenetic relationships were estimated by heuristic searches based on 1 000 random addition sequences and tree bisection-reconnection, with the branch swapping option set on ‘best trees’ only.

All characters were weighted equally and alignment gaps were treated as missing data. Measures calculated for parsimony included tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI) and rescaled consistence index (RC). Bootstrap analysis (Hillis & Bull 1993) was based on 1 000 replications. All sequences for the isolates studied were analysed using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool for Nucleotide sequences (BLASTN, Altschul et al. 1990). The phylogenetic analysis included 19 partial gene sequences per gene, representing eight Calonectria spp. (Table 1) closely related to the isolates studied. Calonectria colombiensis was used as the outgroup taxon. All sequences were deposited in GenBank and the alignments in TreeBASE (http://treebase.org).

Table 1.

Strains of Calonectria (Cylindrocladium) species included in the phylogenetic analyses (TreeBase SN 4332).

| Species | Isolate number1 | β-tubulin2 | Histone H32 | Host | Origin | Collector |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ca. avesiculata (Cy. avesiculatum) | CBS 313.92T | AF333392 | DQ190620 | Ilex vomitoria | USA | S.A. Alfieri |

| Ca. brachiatica sp. nov. | CMW 25293 | FJ716710 | FJ716714 | P. maximinoi | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield |

| CMW 25298 (= CBS 123700)T | FJ696388 | FJ696396 | P. maximinoi | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield | |

| CMW 25302 | FJ716708 | FJ716712 | P. tecunumanii | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield | |

| CMW 25307 | FJ716709 | FJ716713 | P. tecunumanii | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield | |

| Ca. brassicae comb. nov. | CBS 111869T | AF232857 | DQ190720 | Argyreia sp. | South East Asia | |

| CBS 111478 | DQ190611 | DQ190719 | Soil | Brazil | A.C. Alfenas | |

| CMW 25296 | FJ716707 | FJ716711 | P. maximinoi | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield | |

| CMW 25297; CBS123702 | FJ696387 | FJ696395 | P. maximinoi | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield | |

| CMW 25299; CBS123701 | FJ696390 | FJ696398 | P. tecunumanii | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield | |

| Ca. clavata (Cy. flexuosum) | CBS 114557T | AF333396 | DQ190623 | Callistemon viminalis | USA | N.E. El-Gholl |

| CBS 114666T | DQ190549 | DQ190624 | USA | N.E. El-Gholl | ||

| Cy. clavatum (= Cy. gracile) | CBS111776T | AF232850 | DQ190700 | Pinus caribaea | Brazil | C.S. Hodges |

| Ca. colombiensis (Cy. colombiensis) | CBS 12221 | AY725620 | AY725663 | Soil | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield |

| Cy. ecuadoriae | CBS 111406T | DQ190600 | DQ190705 | Soil | Ecuador | M.J. Wingfield |

| Ca. gracilipes (Cy. graciloideum) | CBS 111141T | DQ190566 | DQ190644 | Eucalyptus sp. | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield |

| CBS 115674 | AF333406 | DQ190645 | Soil | Colombia | M.J. Wingfield | |

| Ca. gracilis (Cy. pseudogracile) | CBS 111284 | DQ190567 | DQ190647 | Manilkara sp. | Brazil | P.W. Crous |

| CBS 111807T | AF232858 | DQ190646 | Brazil |

1 CBS: Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Utrecht, The Netherlands; CMW: culture collection of the Forestry and Agricultural Biotechnology Institute (FABI), University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

2 GenBank accession numbers.

T ex-type culture.

A Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithm was used to generate phylogenetic trees with Bayesian probabilities using MrBayes v3.1.1 (Ronquist & Huelsenbeck 2003). Models of nucleotide substitution for each gene were determined using MrModeltest (Nylander 2004) and included for each gene partition. Four MCMC chains were run simultaneously from random trees for one million generations and sampled every 100 generations. The first 800 trees were discarded as the burn-in phase of each analysis and posterior probabilities determined from the remaining trees.

Pathogenicity tests

In order to test the pathogenicity of the Calonectria spp. collected in this study, profusely sporulating isolates CMW 25293, representing Ca. brachiatica, CMW 25296 and CMW 25297, both representing Ca. brassicae, were used for inoculations onto rooted cuttings of P. maximinoi. Isolate CMW 25299, representing Ca. brassicae and isolates CMW 25302 and CMW 25307 representing Ca. brachiatica were used for inoculations onto rooted cuttings of P. tecunumanii. Trees used for inoculation were between 0.5–1 m in height and 10–50 mm diam at the root collar. Trees were maintained in a greenhouse under controlled conditions prior to inoculation, so that they could become acclimatised and to ensure that they were healthy. Sixty trees for each Pinus spp. were used and an additional 60 trees were used as controls. This resulted in a total of 180 trees in the pathogenicity tests.

Inoculations were preformed in the greenhouse by making a 5 mm diam wound on the main stems of plants with a cork borer to expose the cambium. The cambial discs were replaced with an MEA disc overgrown with the test fungi taken from 7 d old cultures. The inoculum discs were placed, mycelium side facing the cambium and the inoculation points were sealed with Parafilm to reduce contamination and desiccation. Control trees were treated in a similar fashion but inoculated with a sterile MEA plug.

Six weeks after inoculation, lesion lengths on the stems of the plants were measured. The results were subsequently analysed using SAS Analytical Programmes v2002. Re-isolations were made from the edges of lesions on the test trees to ensure the presence of the inoculated fungi.

RESULTS

DNA phylogeny

For the β-tubulin gene region, ± 580 bases were generated for each of the isolates used in the study (Table 1). The adjusted alignment included 19 taxa with the outgroup, and 523 characters including gaps after uneven ends were removed from the beginning of each sequence. Of these characters, 459 were constant and uninformative. For the analysis, only the 64 parsimony informative characters were included. Parsimony analysis of the aligned sequences yielded five most parsimonious trees (TL = 231 steps; CI = 0.870; RI = 0.799; RC = 0.695; results not shown). Sequences for the histone gene region consisted of ± 460 bases for the isolates used in the study and the adjusted alignment of 19 taxa including the outgroup, consisted of 466 characters including gaps. Of these characters, 391 were excluded as constant and parsimony uninformative and 79 parsimony informative characters included. Analysis of the aligned data yielded one most parsimonious tree (TL = 290 steps; CI = 0.845; RI = 0.807; RC = 0.682; results not shown).

The partition homogeneity test showed that the β-tubulin and histone dataset could be combined (P = 0.245). The 70 % reciprocal bootstrap method indicated no conflict in tree topology among the two partitions, resulting in a combined sequence dataset consisting of 993 characters including gaps for the 19 taxa (including outgroup). Of these, 850 characters were constant and parsimony uninformative and excluded from the analysis. There were 143 characters in the analysis that were parsimony informative. Parsimony analysis of the combined alignments yielded one most parsimonious tree (TL = 526 steps; CI = 0.848; RI = 0.791; RC = 0.670), which is presented in Fig. 2 (TreeBase SN 4332).

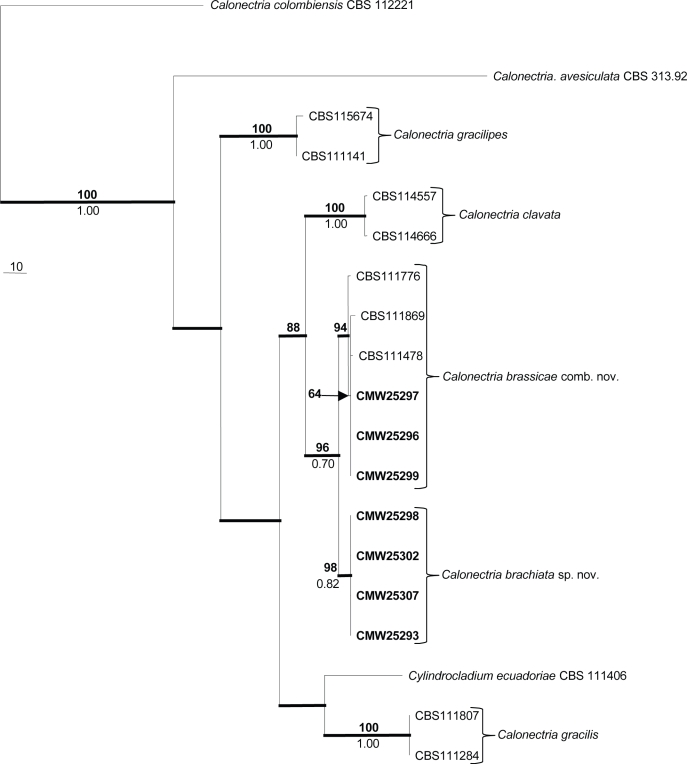

Fig. 2.

The most parsimonious tree obtained from a heuristic search with 1 000 random addition sequences of the combined β-tubulin and histone H3 sequence alignments. Scale bar shows 10 changes and bootstrap support values from 1 000 replicates are shown at the nodes. Bayesian posterior probabilities are indicated below the branches. Bold lines indicate branches present in the Bayesian consensus tree. The tree was rooted with Calonectria colombiensis (CBS 112221).

All the isolates obtained from the Pinus spp. used in this study grouped in the Ca. brassicae species complex with a bootstrap (BP) value of 96 and a low Bayesian posterior probability (PP) of 0.70. This clade was further subdivided into two clades. The first clade (BP = 64, PP below 0.70) representing Ca. brassicae, included the type of Cy. gracile and Cy. clavatum. It also included three isolates (CMW 25297, CMW 25296 and CMW 25299) from P. maximinoi and P. tecunumanii. The second clade (BP = 98, PP = 0.82) accommodated Calonectria isolates (CMW 25293, CMW 25298, CMW 25302 and CMW 25307), representing what we recognise as a distinct species. The consensus tree obtained with Bayesian analysis showed topographical similarities with the most parsimonious tree as indicated in Fig. 2.

Pathogenicity tests

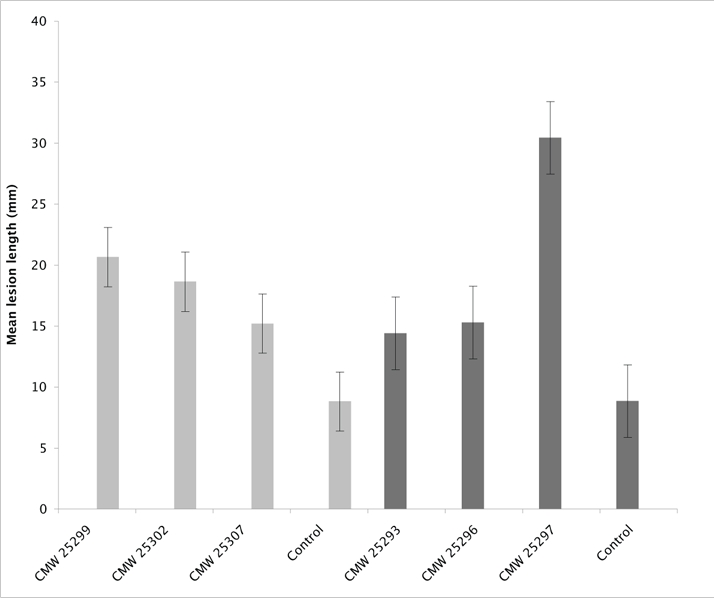

All plants inoculated with Calonectria spp. in this study developed lesions. Lesions included discolouration of the vascular tissue with abundant resin formation, 6 wk after inoculation. Lesions on the control trees were either non-existent or small, representing wound reactions. There were significant (p < 0.0001) differences in lesion lengths associated with individual isolates used on P. maximinoi (Fig. 3). Comparisons of the lesion lengths clearly showed that Ca. brassicae (CMW 25297) produced the longest average lesions (av. = 30.04 mm) compared to the undescribed Calonectria sp. (CMW 25293) (av. = 14.41 mm). The other Ca. brassicae isolate (CMW 25296) produced an average lesion length of 15.30 mm. Lesions on the control trees were an average of 8.84 mm and significantly (p < 0.0001) smaller than those on any of the trees inoculated with the test fungi (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Histogram showing mean lesion lengths induced by each isolate on P. maximinoi (dark grey) and P. tecunumanii (light grey). Calonectria brassicae is represented by CMW 25296, CMW 25297 and CMW 25299; Ca. brachiatica is represented by CMW 25293, CMW 25302 and CMW 25307.

Results of inoculations on P. tecunumanii were similar to those on P. maximinoi. Thus, Ca. brassicae (CMW 25299) (av. = 20.64 mm) produced the longest lesions compared with the undescribed Calonectria sp. (CMW 25302; av. = 18.63 mm and CMW 25307; av. = 15.20 mm). The lesions on the P. tecunumanii control trees were also significantly (p < 0.0001) smaller (av. = 8.82 mm) than those on any of the trees inoculated with the test fungi. Re-isolations from the test trees consistently yielded the inoculated fungi and no Calonectria spp. were isolated from the control trees.

Taxonomy

Isolates CMW 25296, CMW 25297 and CMW 25299 clearly represent Ca. brassicae based on morphological observations (Crous 2002) and comparisons of DNA sequence data. Isolates CMW 25293, CMW 25298, CMW 25302 and CMW 25307 represent an undescribed species closely related to Ca. brassicae but morphologically distinct. Species of Cylindrocladium (1892) represent anamorph states of Calonectria (1867) (Rossman et al. 1999), and therefore this fungus is described as a new species of Calonectria, which represents the older generic name for these holomorphs:

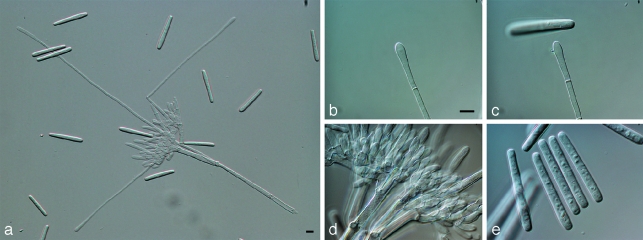

Calonectria brachiatica L. Lombard, M.J. Wingf. & Crous, sp. nov. — MycoBank MB512998; Fig. 4

Fig. 4.

Calonectria brachiatica. a. Macroconidiophore with lateral branching stipe extensions; b, c. clavate vesicles; d. fertile branches; e. macroconidia. — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Stipa extensiones septatum, hyalinum, 134–318 μm, in vesiculam clavatum, 5–7 μm diam terminans. Conidia cylindrica, hyalina, 1–2-septata, utrinque obtusa, (37–)40–48(–50) × 4–6 μm.

Teleomorph. Unknown.

Etymology. Name refers to the stipe extensions on the conidiophore.

Conidiophores with a stipe bearing penicillate suites of fertile branches, stipe extensions and terminal vesicles; stipe septate, hyaline, smooth, 32–67 × 6–8 μm; stipe extensions septate, straight to flexuous, 134–318 μm long, 4–5 μm wide at the apical septum, terminating in a clavate vesicle, 5–7 μm diam; lateral stipe extensions (90° to the axis) also present. Conidiogenous apparatus 40–81 μm long, and 35–84 μm wide; primary branches aseptate or 1-septate, 15–30 × 4–6 μm; secondary branches aseptate, 10–23 × 3–5 μm; tertiary branches and additional branches (–5), aseptate, 10–15 × 3–4 μm, each terminal branch producing 2–6 phialides; phialides doliiform to reniform, hyaline, aseptate, 10–15 × 3–4 μm; apex with minute periclinal thickening and inconspicuous collarette. Conidia cylindrical, rounded at both ends, straight, (37–)40–48(–50) × 4–6 μm (av. = 44 × 5 μm), 1(–2)-septate, lacking a visible abscission scar, held in parallel cylindrical clusters by colourless slime. Mega- and microconidia not seen.

Cultural characteristics — Colonies fast growing with optimal growth temperature at 24 °C (growth at 12–30 °C) on MEA, reverse amber to sepia brown after 7 d; abundant white aerial mycelium with moderate to extensive sporulation; chlamydospores extensive throughout the medium.

Specimens examined. Colombia, Valle del Cauca, Buga, from Pinus maximinoi, July 2007, M.J. Wingfield, holotype PREM 60197, culture ex-type CMW 25298 = CBS 123700; Buga, from P. tecunumanii, July 2007, M.J. Wingfield, culture CMW 25303 = CBS 123699; Buga, from P. tecunumanii, July 2007, M.J. Wingfield, PREM 60198, culture CMW 25341 = CBS 123703.

Notes — The anamorph state of Ca. brachiatica can be distinguished from Cy. gracile, Cy. pseudogracile and Cy. graciloideum by its shorter macroconidia. Another characteristic distinguishing Ca. brachiatica is the formation of lateral branches not reported for Cy. gracile or other closely related species.

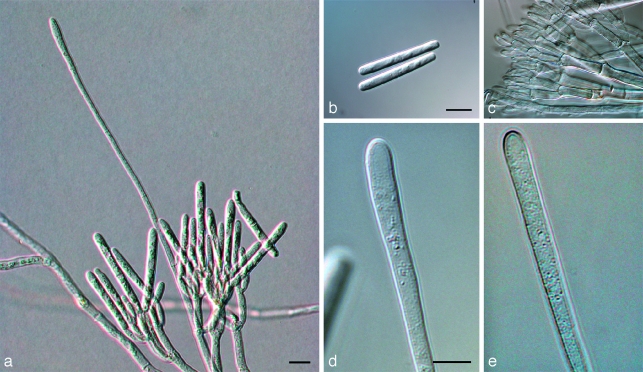

Calonectria brassicae (Panwar & Bohra) L. Lombard, M.J. Wingf. & Crous, comb. nov. — MycoBank MB513423; Fig. 5

Fig. 5.

Calonectria brassicae. a. Macroconidiophore on SNA; b. macroconidia; c. fertile branches; d, e. clavate vesicles. — Scale bars = 10 μm.

Basionym. Cylindrocladium brassicae Panwar & Bohra, Indian Phytopathol. 27: 425. 1974.

= Cylindrocarpon gracile Bugnic., Encycl. Mycologique 11: 162. 1939.

≡ Cylindrocladium gracile (Bugnic.) Boesew., Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc. 78: 554. 1982.

= Cylindrocladium clavatum Hodges & L.C. May, Phytopathology 62: 900. 1972.

Notes — Both the names Ca. clavata and Ca. gracilis and are already occupied, hence the oldest available epithet is that of Cy. brassicae (Crous 2002).

DISCUSSION

Results of this study show that Calonectria spp. are important pathogens in pine cutting nurseries in Colombia. In this case, two species were discovered, the one newly described here as Ca. brachiatica and the other representing Ca. brassicae (Fig. 5). Both of the species were pathogenic on P. maximinoi and P. tecunumanii.

The description of Ca. brachiatica from P. maximinoi and P. tecunumanii adds a new species to the Ca. brassicae species complex, which already includes six other Calonectria spp. (Crous 2002, Crous et al. 2006). This species can be distinguished from the other species in the complex by the formation of lateral branches on the macroconidiophores and the presence of a small number of 2-septate macroconidia. Macroconidial dimensions (av. = 44 × 5 μm) are also smaller then those of Ca. brassicae (av. = 53 × 4.5 μm; Fig. 5).

A recent study of Calonectria species with clavate vesicles by Crous et al. (2006) attempted to resolve the taxonomic status of these species, and added two new species to the group. Crosses among isolates of Ca. brachiatica and isolates of Ca. brassicae, did not result in sexual structures in the present study, and teleomorphs are rarely observed in this species complex.

Hodges & May (1972) reported Ca. brassicae (as Cy. clavatum) from several Pinus spp. in nurseries and plantations in Brazil. Subsequent studies based on comparisons of DNA sequence data revealed Cy. clavatum to be a synonym of Cy. gracile (Crous et al. 1995, 1999, Schoch et al. 2001). Calonectria brassicae (as Cy. gracile) is a well-known pathogen of numerous plant hosts in subtropical and tropical areas of the world. However, in Colombia, this plant pathogen has been isolated only from soil (Crous 2002, Crous et al. 2006). This study thus represents the first report of Ca. brassicae infecting Pinus spp. in Colombia.

Pathogenicity tests with isolates of Ca. brachiatica and Ca. brassicae clearly showed that they are able to cause symptoms similar to those observed in naturally infected plants. Both P. maximinoi and P. tecunumanii were highly susceptible to infection by Ca. brassicae. This supports earlier work of Hodges & May (1972) in Brazil, where they reported a similar situation. In their study, seven Pinus spp. were wound-inoculated with Ca. brassicae and this resulted in mortality of all test plants within 2 wk. Although they did not include P. maximinoi and P. tecunumanii in the study, they concluded that the pathogen is highly virulent and regarded it as unique in causing disease symptoms in established plantations of Pinus spp. No disease symptoms associated with Ca. brachiatica or Ca. brassicae were seen in established plantations in the present study and we primarily regard these fungi as nursery pathogens, of which the former species is more virulent than the latter.

The use of SNA (Nirenburg 1981) rather than carnation leaf agar (CLA; Fisher et al. 1982) for morphological descriptions of Calonectria spp. represents a new approach employed in this study. Previously, species descriptions for Calonectria have typically been conducted on carnation leaf pieces on tap water agar (Crous et al. 1992). However, carnation leaves are not always readily available for such studies and SNA, a low nutrient medium, also used for the related genera Fusarium and Cylindrocarpon spp. identification (Halleen et al. 2006, Leslie & Summerell 2006), provides a useful medium for which the chemical components are readily available. Another advantage of using SNA is its transparent nature, allowing direct viewing through a compound microscope as well as on mounted agar blocks for higher magnification (Leslie & Summerell 2006). In this study, it was found that the Calonectria isolates sporulate profusely on the surface of SNA and comparisons of measurements for structures on SNA and those on CLA showed no significant difference. However, CLA remains important to induce the formation of teleomorph structures in homothallic isolates or heterothallic isolates for which both mating types are present.

KEY TO CALONECTRIA SPECIES WITH CLAVATE VESICLES AND PREDOMINANTLY 1-SEPTATE MACROCONIDIA (To Be inserted in Crous 2002, P. 56, Couplet No. 2)

-

2.

Stipe extension thick-walled; vesicle acicular to clavate……………Cy. avesiculatum

-

2.

Stipe extension not thick-walled; vesicle clavate……………3

-

3.

Teleomorph unknown……………4

-

3.

Teleomorph readily formed……………7

-

4.

Macroconidia always 1(–2)-septate……………5

-

4.

Macroconidia 1(–3)-septate……………6

-

5.

Macroconidia 1-septate, (38–)40–55(–65) × (3.5–)4–5(–6) μm, av. = 53 × 4.5 μm; lateral stipe extensions absent……………Ca. brassicae

-

5.

Macroconidia 1(–2)-septate, (37–)40–48(–50) × 4–6 μm, av. = 44 × 5 μm; lateral stipe extensions present……………Ca. brachiatica

-

6.

Macroconidia (48–)57–68(–75) × (6–)6.5(–7) μm, av. = 63 × 6.5 μm……………Cy. australiense

-

6.

Macroconidia (45–)48–55(–65) × (4–)4.5(–5) μm, av. = 51 × 4.5 μm……………Cy. ecuadoriae

-

7.

Macroconidial state absent; megaconidia and microconidia present……………Ca. multiseptata

-

7.

Macroconidial state present……………8

-

8.

Teleomorph homothallic……………9

-

8.

Teleomorph heterothallic……………10

-

9.

Perithecia orange; macroconidia av. size = 45 × 4.5 μm……………Ca. gracilipes

-

9.

Perithecia red; macroconidia av. size = 56 × 4.5 μm……………Ca. gracilis

-

10.

Perithecia orange; macroconidia av. size = 32 × 3 μm……………Ca. clavata

-

10.

Perithecia red-brown; macroconidia av. size = 30 × 3 μm……………Ca. pteridis

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Tree Protection Cooperative Programme (TPCP), the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS) and the University of Pretoria for financial support to undertake this study. The first author further acknowledges Drs J.Z. Groenewald and G.C. Hunter for advice regarding DNA sequence analyses.

REFERENCES

- Ahmad N, Ahmad S. 1982. Needle disease of pine caused by Cylindrocladium macrosporum. The Malaysian Forester 45: 84 – 86 [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology 215: 403 – 410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell CE, Skilling DD. 1975. Forest nursery diseases in the U.S.A.7. Cylindrocladium root rot. U.S.D.A. Forest Service Handbook No. 470: 23 – 26 [Google Scholar]

- Cox RS. 1953. Etiology and control of a serious complex of diseases of conifer seedlings. Phytopathology 43: 469 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW. 2002. Taxonomy and pathology of Cylindrocladium (Calonectria) and allied genera APS Press; , St. Paul, Minnesota, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Risède J-M, Simoneau P, Hyde KD. 2006. Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: species with clavate vesicles. Studies in Mycology 55: 213 – 226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Groenewald JZ, Risède J-M, Simoneau P, Hywel-Jones N. 2004. Calonectria species and their Cylindrocladium anamorphs: species with sphaeropedunculate vesicles. Studies in Mycology 50: 415 – 430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Kang JC, Schoch CL, Mchua GRA. 1999. Phylogenetic relationships of Cylindrocladium pseudogracile and Cylindrocladium rumohrae with morphologically similar taxa, based on morphology and DNA sequences of internal transcribed spacers and β-tubulin. Canadian Journal of Botany 77: 1813 – 1820 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Korf A, Zyl WH van. 1995. Nuclear DNA polymorphisms of Cylindrocladium species with 1-septate conidia and clavate vesicles. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 18: 224 – 250 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Phillips AJL, Wingfield MJ. 1991. The genera Cylindrocladium and Cylindrocladiella in South Africa, with special reference to forest nurseries. South African Journal of Forestry 157: 69 – 85 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Phillips AJL, Wingfield MJ. 1992. Effects of cultural conditions on vesicle and conidium morphology in species of Cylindrocladium and Cylindrocladiella. Mycologia 84: 497 – 504 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Wingfield MJ. 1994. A monograph of Cylindrocladium, including anamorphs of Calonectria. Mycotaxon 51: 341 – 435 [Google Scholar]

- Crous PW, Wingfield MJ, Mohammed C, Yuan ZQ. 1998. New foliar pathogens of Eucalyptus from Australia and Indonesia. Mycological Research 102: 527 – 532 [Google Scholar]

- Darvas JM, Scott DB, Kotze JM. 1978. Fungi associated with damping – off in coniferous seedlings in South African nurseries. South African Forestry Journal 104: 15 – 19 [Google Scholar]

- Farris JS, Källersjö M, Kluge AG, Bult C. 1994. Testing significance of incongruence. Cladistics 10: 315 – 320 [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira FA, Alfenas AC, Moreira AM, Demuner NLJ. 1995. Foliar eucalypt disease in tropical regions of Brasil caused by Cylindrocladium pteridis. Fitopatologia Brasileira 20: 107 – 110 [Google Scholar]

- Fisher NL, Burgess LW, Toussoun TA, Nelson PE. 1982. Carnation leaves as a substrate and for preserving cultures of Fusarium species. Phytopathology 72: 151 – 153 [Google Scholar]

- Gadgill PD, Dick MA. 2004. Fungi silvicolae novazelandiae: 5. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 34: 316 – 323 [Google Scholar]

- Graves AH. 1915. Root rot of coniferous seedlings. Phytopathology 5: 213 – 217 [Google Scholar]

- Halleen F, Schroers H-J, Groenewald JZ, Rego C, Oliveira H, Crous PW. 2006. Neonectria liriodendri sp. nov., the main causal agent of black foot disease of grapevines. Studies in Mycology 55: 227 – 234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis DM, Bull JJ. 1993. An empirical test of bootstrapping as a method for assessing confidence in phylogenetic analysis. Systematic Biology 42: 182 – 192 [Google Scholar]

- Hodges CS, May LC. 1972. A root disease of pine, Araucaria, and Eucalyptus in Brazil caused by a new species of Cylindrocladium. Phytopathology 62: 898 – 901 [Google Scholar]

- Jackson LWR. 1938. Cylindrocladium associated with diseases of tree seedlings. Plant Disease Reporter 22: 84 – 85 [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Kuma K, Toh H, Miyata T. 2005. MAFFT v5: improvement in accuracy of multiple sequence alignment. Nucleic Acid Research 33: 511 – 518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie JF, Summerell BA. 2006. The Fusarium laboratory manual Blackwell Publishing, Iowa, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Lombard L, Bogale M, Montenegro F, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. 2008. A new bark canker disease of the tropical hardwood tree Cedrelinga cateniformis in Ecuador. Fungal Diversity 31: 73 – 81 [Google Scholar]

- Mason-Gamer RJ, Kellogg EA. 1996. Testing for phylogenetic conflict among molecular data sets in the tribe Triticeae (Gramineae). Systematic Biology 45: 524 – 545 [Google Scholar]

- Mohanan C, Sharma JK. 1985. Cylindrocladium causing seedling diseases of Eucalyptus in Kerala, India. Transactions of the British Mycological Society 84: 538 – 539 [Google Scholar]

- Nelson PE, Toussoun TA, Marasas WFO. 1983. Fusarium species – an illustrated manual for identification: 5–18 The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA: [Google Scholar]

- Nirenburg HI. 1981. A simplified method for identifying Fusarium spp. occurring on wheat. Canadian Journal of Botany 59: 1599 – 1609 [Google Scholar]

- Nylander JAA. MrModeltest v2. Programme distributed by the author. Evolutionary Biology Centre, Uppsala University; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell K, Cigelnik E. 1997. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 7: 103 – 116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner RW. 1970. A mycological colour chart British Mycological Society, Commonwealth Mycological Institute, Kew, Surry: [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F, Huelsenbeck JP. 2003. MrBayes 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics 19: 1572 – 1574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossman AY, Samuels GJ, Rogerson CT, Lowen R. 1999. Genera of Bionectriaceae, Hypocreaceae and Nectriaceae (Hypocreales, Ascomycetes). Studies in Mycology 42: 1 – 248 [Google Scholar]

- Schoch CL, Crous PW, Wingfield BD, Wingfield MJ. 2001. Phylogeny of Calonectria based on comparisons of β-tubulin DNA sequences. Mycological Research 105: 1045 – 1052 [Google Scholar]

- Sharma JK, Mohanan C, Florence EJM. 1984. Nursery diseases of Eucalyptus in Kerala. European Journal of Forest Pathology 14: 77 – 89 [Google Scholar]

- Sobers EK, Alfieri SA. 1972. Species of Cylindrocladium and their hosts in Florida and Georgia. Proceedings of the Florida State Horticultural Society 85: 366 – 369 [Google Scholar]

- Swofford DL. 2002. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and other methods), 4.0b10. Computer programme Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts, USA: [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi T, Tanaka C, Tamai S, Yamanaka N, Futai K. 2008. Identification of Cylindrocladium sp. causing damping-off disease of Japanese black pine (Pinus thunbergii) and factors affecting the disease severity in a black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia)-dominated area. Journal of Forest Research 13: 233 – 240 [Google Scholar]

- Thies WF, Patton RF. 1970. The biology of Cylindrocladium scoparium in Wisconsin forest tree nurseries. Phytopathology 60: 1662 – 1668 [Google Scholar]