Abstract

Metazoan growth and development is maintained by populations of undifferentiated cells, commonly known as stem cells. Stem cells possess several characteristic properties, including dividing through self-renewing divisions and generating progeny that differentiate to have specialized cell fates. Multiple signaling pathways have been identified which coordinate stem cell proliferation with maintenance and differentiation. Relatively recently, the small, non-protein coding microRNAs (miRNAs) have been identified to function as important regulators in stem cell development. Individual miRNAs are capable of directing the translational repression of many mRNAs targets, generating widespread changes in gene expression. In addition, dysfunction of miRNA expression is commonly associated with cancer development. Cancer stem cells, which are likely responsible for initiating and maintaining tumorigenesis, share many similarities with stem cells and some mechanisms of miRNA function may be in common between these two cell types.

Key words: stem cell, miRNA, mammalian, neuroblast, pluripotency, cancer, ESC, self-renewal

Stem Cell Proliferation and Differentiation

Tissue growth, homeostasis and repair in many organ systems are regulated by a pool of precursor cells commonly known as stem cells. Stem cells exist in an undifferentiated state, capable of proliferating over extended periods of time through self renewing divisions. The progeny born from asymmetrical stem cell divisions are mitotically active, increasing in number before differentiation into a variety of cells that contribute to organ formation and function.

Stem cells can be broadly classified as either being embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or adult stem cells. ESCs are derived from the inner cell mass of preimplantation mammalian blastocysts and are termed pluripotent due to their capacity to differentiate into the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm) that give rise to all of the tissues of the developing embryo.1,2 This attribute, in conjunction with the ability of researchers to induce lineage-specific differentiation of cultured ESCs, provides optimism that stem cells can be utilised as a therapeutic tool in the treatment of various human diseases. In contrast, adult stem cells are found in various tissues of the body, where they have tissue specific roles in growth and maintenance. Adult stem cells are considered multipotent and can proliferate indefinitely, similarly to ESCs, but are only capable of producing a limited number of differentiated cell types in vivo. Although, questions remain regarding the potency of different cell populations, illustrated by the example that adult neural stem cells can be transformed into pluripotent cells simply by expressing the pluripotent stem cell marker POU class 5 homeobox 1 (POU5F1/Oct4).3

The mechanisms that control stem cell proliferation, self-renewal and differentiation must be carefully regulated to ensure stem cells are not lost due to inappropriate differentiation and that the self renewing capacity and long term continuous proliferation is restricted to the stem cell. Maintaining the ‘stemness’ of these cells involves a complex regulatory network of extrinsic and intrinsic factors in conjunction with chromatin remodelling.4,5 Dysfunction of these regulators can result in inappropriate cell cycle progression, differentiation and/or cell survival, commonly associated with cancer. Relatively recently a family of non-protein-coding RNAs, the miRNAs, have been identified to have incredibly important roles in stem cell proliferation, pluripotency and differentiation as well as cancer initiation and progression.

miRNA Biogenesis

Mature miRNAs are an abundant family of endogenous, non-coding RNA transcripts, 19–25 nucleotides in length that negatively regulate gene expression post-transcriptionally. miRNAs were originally identified in Caenorhabditis elegans almost two decades ago,6,7 however the discovery of miRNAs in other genomes was only made in the last decade. The continual development of strategies to detect miRNAs has generated over 700 confirmed human miRNAs, listed on the publicly accessible miRNA database, miRBase (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/), although estimates predict up to 1,000 miRNAs could be present.8 Many miRNAs are conserved between distantly related organisms, suggestive of roles in essential biological functions. miRNAs have now been shown to regulate most aspects of development including stem cell growth and differentiation.

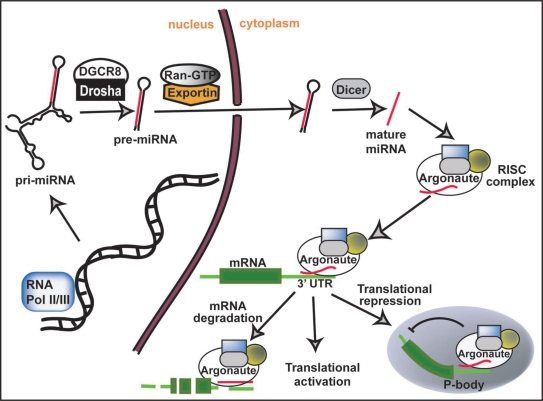

miRNAs are found scattered throughout mammalian genomes, and can be found as isolated transcriptional units, co-transcribed as part of other transcriptional units, or clustered together and transcribed as polycistronic primary transcripts.9 Mature miRNAs are formed by multiple processing steps, beginning with the transcription of the primary (pri) miRNA transcript by RNA polymerases II and III.10,11 Pri-miRNAs, which can be thousands of nucleotides in length, form stem-loop structures that are 5′ capped and contain 3′ poly (A) tail.12 Pri-miRNAs go through two cleavage processes to generate mature miRNAs (Fig. 1). Firstly pri-miRNA transcripts are cleaved by a nuclear microprocessor complex containing the RNaseIII enzyme Drosha and the double stranded RNA-binding domain protein DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 (DGCR8), to produce precursor (pre)-miRNAs.13,14 Pre-miRNAs, which are around 70 nucleotides in length, are exported from the nucleus by Exportin 5 and Ran-GTP.15 Within the cytoplasm the hairpin-like pre-miRNAs are further cleaved by the RNAse III enzyme Dicer to generate two complementary RNA fragments, of which one is the mature miRNA.16,17 Both the nuclear pri-miRNA and cytoplasmic pre-miRNA cleavage steps are points at which miRNA processing can be regulated. In fact a general inhibition of Drosha-mediated processing of many pri-miRNAs appears to be an important mechanism during early mouse development.18 Similarly the expression of a miRNA can be differentially regulated during development in a tissue specific manner by restricting the Dicer-mediated processing of the pre-miRNA.19 One factor identified to have the capability of inhibiting the processing of let7 miRNAs both at the Drosha and Dicer cleavage steps is the RNA-binding protein Lin28.20–23 Lin28 is specifically expressed in mouse and human ESCs and downregulated upon differentiation, restricting mature let7 expression to differentiating tissue. Accordingly, the post-transcriptional regulation of mature miRNAs would allow cells to respond rapidly to developmental changes, by simply relieving the cleavage inhibition.

Figure 1.

miRNA biogenesis and activity. miRNAs are transcribed from multiple genomic loci and processed by two cleavage steps to generate a mature 19–25 nucleotide long RNA fragment. Mature miRNAs direct the RISC complex to target mRNAs, resulting in either an upregulation of translation, but more commonly mRNA degradation and translational inhibition. See text for more details.

miRNA Function

miRNAs repress the translation of target mRNAs by means of the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC).24,25 Mature miRNAs are loaded onto an Argonaute family member protein, which constitutes the catalytic portion of the multi-protein RISC. The miRNA then directs the RISC complex to mRNAs which share sequence complementation with the nucleotides at positions 2–8 of the 5′ end of the mature miRNA, commonly referred to as the ‘seed sequence’.26 Complementation between the seed sequence and the 3′ untranslated region (3′UTR) of the mRNA is sufficient for target recognition, while the remainder of the miRNA sequence can share varying degrees of complementation, with an increased complementation enhancing miRNA functionality.27 The stability of miRNA:mRNA interactions has recently been discovered to be enhanced by the presence of conserved motifs found downstream of the miRNA target site.28 Perfect complementation between the entire miRNA and the 3′UTR results in mRNA transcript degradation, while imperfect complementation generally results in a translational suppression.29–31 The mode by which the RISC mediates translational repression is not entirely understood but it appears that the complex sequesters target mRNAs to cytoplasmic processing bodies (P-bodies), resulting in the inhibition of translation.32,33 Although miRNAs are generally described as having a repressive action, they have also been shown to upregulate expression of target mRNAs.34 This appears partly due to the targeting of regulators involved in the alternative splicing of mRNAs.35,36

Given that the minimal seed sequence requires as few as 6–7 nucleotides, individual miRNAs are predicted to and experimentally proven to target hundreds of mRNAs.30,37 Not only can individual miRNAs target many gene transcripts, but miRNAs produced from a polycistronic cluster commonly share considerable sequence homology and are likely to regulate common transcript targets.38 In addition mRNAs can possess more than one miRNA binding site and therefore be regulated simultaneously or within different developmental contexts by multiple miRNAs.39 In fact as much as one third of the expressed genome has been predicted to be regulated by miRNAs.40 Future computational analysis of predicted targets for miRNAs will need to be backed up with expression profiling, involving the ectopic expression and inhibition of miRNAs, in order to identify all targets for individual miRNAs.

Surprisingly, evidence suggests miRNAs exert only subtle changes on protein expression, generally downregulating expression by less than two fold, indicative that miRNAs act to fine-tune protein expression rather than producing an ON/OFF effect.30,37 In fact, several studies have noted that the expression of target mRNAs is generally low in tissues which express the targeting miRNA.29,41,42 The prime function of miRNAs may therefore be to ensure target mRNA expressions are kept at basal levels in these tissues.

Expression of miRNAs in ESCs

Concurrent to the continual discovery of miRNAs within mammalian genomes, studies have been conducted to analyse the expression profiles of individual miRNAs. Noticeably, miRNAs are dynamically regulated between cell-types and developmental stages.43–46 Early studies began to identify miRNAs that were differentially expressed between ESCs and their differentiated progeny in mouse and human.47,48 Such dynamic expression profiles suggest these miRNAs play important roles in maintaining stem cell self-renewal and pluripotency, or regulating the differentiation of their progeny cells.

Each ESC is estimated to have around 110,000 miRNA transcripts, which are comprised of over 300 separate miRNAs,49 however, the majority of these miRNAs were found at relatively low levels, when compared with other tissues. In fact most miRNAs expressed in ESCs originate from just four loci, namely the miR-15b/miR-16 cluster, miR17–92 cluster, miR-21, and the miR-290–295 cluster.49,50 Moreover the miR-290–295 cluster itself makes up over 70% of the total miRNA molecules present in murine ESCs (mESCs). Many of the miRNAs upregulated in ESCs share a common consensus seed sequence, suggestive they target a common group of targets mRNAs.51 The four prominently expressed miRNA clusters have all been previously implicated in cell cycle progression and oncogenesis, consistent with cell cycle regulation being an integral part of stem cell control. This is discussed in further detail in later sections. Although the expression of certain miRNAs are upregulated in ESCs, global miRNA expression is lower in ESCs when compared to differentiated cells, which would suggest that miRNAs play important roles in promoting or maintaining a differentiated state.52 However, miRNAs that are specifically expressed in ESCs appear to play essential roles in regulating stem cell pluripotency and proliferation.

Interestingly, it has recently been shown that miRNAs can be transported between cells by means of microvesicles.53 ESC microvesicles contain a subset of the expressed miRNAs, which have the capacity to fuse with neighbouring cells. This observation generates an intriguing mechanism, in which miRNAs could act as signaling molecules to regulate posttranscriptional mechanisms within a local environment.

Global Disruption of Mature miRNA

The role of miRNAs in murine ESC development has been studied by globally disrupting mature miRNA processing using both Dicer1 and Dgcr8 knock-out models. Homozygous Dicer1 knockout mice exhibit early embryonic lethality (E7.5) and fail to express the pluripotent marker Oct4.54 The apparent absence of ESCs in these Dicer1 mutant embryos is likely to be due in part to a disrupted proliferation, as conditional Dicer1 mutant mESCs are in fact viable.55 Although these conditional Dicer1 mutant mESCs express the pluripotency marker Oct4 and appear normal, upon attempting to induce differentiation they fail to express both endodermal and mesodermal markers, while continuing to express Oct4.56 Similarly the conditional knockout of Dgcr8 in mESCs also disrupts differentiation as judged by the fact that these cells maintain expression of the pluripotency markers Oct4 and Nanog homeobox (Nanog).57 Therefore it appears miRNAs facilitate differentiation of ESCs by downregulating the expression of pluripotency factors.

Mutual Regulation between miRNAs and Transcription Factors is Required for Pluripotency

Transcription factors which are essential for maintaining the pluripotency of ESCs have been identified to be important regulators of miRNA expression. It has been noted that miRNAs which have a promoter region predicted to be occupied by these pluripotency factors can have expression levels up to 1,000 fold higher in ESCs than that detected in various differentiated cells.50 In a mutual regulatory feedback loop, not only do these pluripotency factors regulate ESC specific miRNAs, but the pluripotency factors are also targets for miRNAs during ESC development and differentiation. During wild-type ESC differentiation, Oct4 expression is downregulated due to de novo methylation of the promoter region.58 Disruption to de novo methylation, as observed in Dicer1 mutant ESCs,56 can explain the persistent expression of Oct4 observed in these cells. It has recently been shown that the miR-290 cluster can also indirectly regulate de novo methylation in ESCs and hence Oct4 expression.59,60 The miR-290 cluster, which is normally expressed in ESCs and downregulated upon differentiation, is believed to directly target the transcriptional repressor, Retinoblastoma-like 2 transcript (Rbl2). An upregulation of Rbl2 expression, as seen in Dicer-1 null cells, results in the repression of DNA methyltransferases, the continual expression of Oct4 and as a result an inability to successfully differentiate.

miRNAs that directly target the self-renewing factors to promote differentiation have also been identified. miR-145 has been shown to be capable of directly targeting the transcripts of Oct4, SRY-box containing gene 2 (Sox2) and Kruppel-like factor 4 (KLF4), thereby facilitating cell differentiation.61 miR-145 is normally repressed in human ESCs (hESCs) by the actions of Oct4, but is significantly upregulated upon differentiation. Loss of miR-145 results in the elevated expression of these self-renewing factors, impairing differentiation. The induction of mouse ESC differentiation with retinoic acid also correlates with an increase in miR-134 expression.62 miR-134 can promote differentiation by directly targeting Nanog and Liver receptor homologue 1 (LRH1), both positive regulators of Oct4 expression.

miRNA-Directed Reprogramming of Differentiated Cells

Although the therapeutic utility of ESCs in the treatment of human diseases has great potential, harvesting these cells from embryos is an extremely controversial issue. In 2006, researchers sidestepped this ethical hurdle by genetically reprogramming somatic cells to have ESC like properties.63 These cells, termed induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSs), were generated by the ectopic expression of four pluripotency factors (Oct4, Sox2, Klf4 and c-Myc). However, the therapeutic potential of these cells was tempered by the fact that they ectopically express the proto-oncogene c-myc. Unsurprisingly, animals experimentally derived from these cells bore a high tumor load.64 Recently alternative strategies have been sought to derive iPSs using miRNAs, thus avoiding concern associated with overexpressing oncogenes.

Indeed, miRNAs have recently shown promise in transforming differentiated cells towards a pluripotent state. Expression of the miR-290 cluster in conjunction with Oct4, Sox2 and Klf4 can improve the dedifferentiation efficiency of fibroblasts into iPSs.65 Although the promoter region of the miR-290 cluster can in fact be bound by c-Myc and is likely to be one of many c-Myc targets, substituting the ectopic expression of c-Myc with that of the miR-290 cluster may have significant advantages for using these cells therapeutically. For instance, the pluripotent cells were more homogeneous, less proliferative and do not show invasive characteristics associated with tumors. In addition, iPSs have also been derived from human somatic fibroblasts by ectopically expressing the miRNA processing inhibitory factor, Lin28, in conjunction with Nanog, Oct-4 and Sox2.66 Although Lin28 was observed to enhance the reprogramming efficiency, it was noted that it was not absolutely required for the initial reprogramming or for the continual proliferation of the iPSs.

The expression of the miR-302 cluster has also been shown to be sufficient to alter the gene expression profile of a human melanoma cell line so that it resembles that of ESCs.67 These so called miRNA induced pluripotent stem (mirPS) cells shared 86% of their expression profiles with that of ESCs, suggesting that the miR-302 cluster can regulate thousands of genes both directly and indirectly. In addition to the induction of ESC markers in these mirPS cells, including Oct3/4, Stage-specific embryonic antigen-3 (SSEA-3), SSEA-4, Sox2 and Nanog, the genome became highly demethylated, one of the hallmarks of ESCs.

Function of miRNAs in Adult Stem Cells

Roles for miRNAs in adult stem cells are not as well defined as they are for ESCs, mainly due to the difficulty in identifying the stem cell populations in many tissues. However, increasing evidence suggests that miRNAs play equally important roles in maintenance and differentiation in these stem cell populations. For example, an overall function for miRNAs in the epidermis of mice was assessed by deleting Dicer1.68 These mice showed a significant reduction in hair-follicle proliferation, in addition to an inability to maintain the follicle stem cell population.

The mammalian hematopoietic system has been studied for over half a century and is the most well understood hierarchical system regarding stem cell growth and lineage precursor differentiation. Expression of miRNAs has been identified in hematopoietic cells and evidence suggests some of these miRNAs play important roles in modulating the lineage differentiation.69 The expression of miR-181 was identified in undifferentiated progenitor cells and found to be upregulated in differentiated B-lymphoid cells. Ectopic expression of miR-181 in cultured hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) induces a doubling in the number of B-lymphoid lineage cells, without affecting the T-cell lineage. Similarly, the ectopic expression of miR-181 within HSCs of mice also leads to a significant increase in the number of B-lymphoid cells, accompanied by a significant decrease in T-lymphoid cells. On the other hand, an increase in the number of cells in the T-lymphoid lineage was observed when miR-223 and miR-142 were overexpressed, without any effect on the B-lymphoid cell lineage.

In addition, recent evidence has shown that differentiation of adult neural stem cells requires miR-124.70 Knockdown of miR-124, which is normally expressed in differentiating neuroblasts, resulted in the maintenance of transit amplifying proliferative precursors in the subventricular zone, while ectopic expression of miR-124 promoted neuronal differentiation. Sox9 was identified to be a direct target of miR-124 and downregulating of Sox9 was essential for neuronal differentiation.

miRNA Coordinated Cell Cycle Progression

Correct cell cycle progression is essential throughout development, with deregulation commonly linked to cancer formation. Cell proliferation is coordinated by the expression of cyclins and phosphorylation of cell cycle targets by cyclin-dependent kinases (cdks). Compared to most other somatic cells, ESCs possess very short G1 phases, which is thought to be a consequence of the rapid growth needed in developing embryos.71 ESCs depleted of Dgcr8 or Dicer1 have been observed to have much slower proliferation rates, accompanied by an accumulation of cells in G1,55,57 illustrating the role miRNAs play in shaping the distinct cell cycle profile of ESCs.

Recently, in an elegant study by Robert Blelloch and colleagues, an attempt was made to identify the miRNAs responsible for the cell cycle defects observed in Dgcr8 knockout ESCs. In vitro derived miRNAs were individually reintroduced into Dgcr8 deficient cells and the resulting proliferation was monitored to see if the characteristically rapid G1/S transition was restored. This study identified fourteen miRNAs that could partially rescue the proliferation defects seen in both Dgcr8 as well as Dicer1 mutant ESCs.72 Further analysis revealed that three miRNAs (miR-291, miR-294 and miR-295) could individually fully rescue the G1/S transition defect. Additionally, eleven of the fourteen miRNAs capable of ameliorating the cell cycle defect share a common seed sequence conserved between the miR-290 and miR-302 clusters, suggesting a regulation of common targets. Among the many hundreds of potential targets of miR-294, this study revealed upregulated expression of the Cyclin E-cdk2 inhibitors; Rbl2, Lats and p21 (CDKN1A) in Dgcr8 knockout cells, which are likely to be directly repressed by the miR-290 cluster in order to promote rapid G1/S transition in ESCs.

The miR-302 cluster has also provided a direct link between miRNAs, cell cycle progression and pluripotency of ESCs. The miR-302 cluster, which is directly regulated by pluripotency factors, is capable of directly targeting the G1 to S phase regulators, Cyclin D1 and D2.73,74 In fact the ectopic expression of miR-302a in somatic cells results in extended S-phase and a shortened G1 phase, suggesting acceleration through the growth phase, similar to ESCs.73 Abolishing miR-302 activity has the opposite effect with an accumulation in G1 phase.74

In addition, miR-92b has been shown to promote the rapid G1 to S phase transition of ESCs by targeting the cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor and, therefore, negative regulator, p57 (CDKN1C).75 Expression of miR-92b is normally upregulated in human ESCs and downregulated upon differentiation. An increase in the number of ESCs in G1 phase was observed when the activity of miR-92 was attenuated. Thus, miRNAs potentially coordinate stem cell division with differentiation by controlling both cell cycle targets and differentiation factors.

A Role for miRNAs in Cancer

Cancers develop from cells which accumulate multiple mutations, allowing unrestrictive cellular proliferation while impairing apoptosis. Cancer cells share similarities with stem cells, including the ability to divide continuously through self-renewing divisions but also producing differentiated progeny. In fact, gene expression profiles were observed to be highly similar between human embryonal carcinoma cells and hESCs.76 This is highly suggestive that at least some developmental pathways important in the regulation of both proliferation and differentiation may be shared between these two cell populations. Evidence now suggests that a number of similarities exist between stem cells and cancer cells regarding miRNA expression and that miRNA dysfunction has a significant role in driving cancer development.77,78

Tumors are a heterogeneous population of cells, containing cells in varying degrees of differentiation. The majority of cells within a tumor have limited proliferation potential, while tumor growth is sustained by a group of cells with self-renewing capabilities, known as the cancer stem cells (CSCs).79 CSCs are of particular importance in cancer research because of their resistance to chemotherapeutic agents, rendering them the likely cause of many cases of tumor relapse.80,81 Initial studies involving the transplantation of acute myeloid leukaemia cells into immunodeficient mice suggested as few as one in a million cells had self renewing capabilities and could seed further tumors,79,82 while other studies have found tumor-propagating cells can be a major constituent, up to 25% of the cells contained within a tumor.83,84 Such striking differences likely reflects the diversity associated with both tumor type and origin. Although the source of CSCs is highly debated, they are most likely to derive from adult tissue stem cells. A recent study in the mouse intestinal epithelium demonstrated that efficient generation of microadenomas was only achieved when the Adenomatous polyposis coli (Apc) tumor suppressor gene was mutated in intestinal epithelial stem cells, while growth of microadenomas rapidly stalled if the mutations were initiated in proliferative, non-stem cells.85

Strikingly, the expression profiles of miRNAs from many cancers resemble that of stem cells. Although the expression of some miRNAs are elevated in certain cancers, tumors and cancer cell lines generally display lower levels of miRNAs compared with normal tissues.86–88 These findings, in conjunction with the observations that Dicer1 and Drosha mutant ESCs fail to differentiate, adds further support to the theory that miRNAs may function primarily to drive terminal differentiation and prevent cell division.87 miRNA loci have been reported to be commonly associated with chromosomal regions frequently amplified, deleted or rearranged in cancer cells.89 Accumulating evidence now suggests that deregulation of miRNA activity can directly influence cancer development and that miRNAs are capable of acting both as tumor suppressors as well as oncogenes.

miRNAs can Act as Tumor Suppressors

A direct link between miRNAs and cancer was initially made with the discovery that the expression of miR-15 and miR-16 were downregulated in more than half of patients with B cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (B-CLL).90 One of the targets of the miR-15/16 cluster was discovered to be the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl2.91 Bcl2 expression levels inversely correlate with the expression levels of miR-15 and 16. In addition, apoptosis could be induced in leukemic cell lines by repressing Bcl2 post-transcriptionally with miR-15/16.

The general inhibition of mature miRNAs, produced by disrupting either Dicer1, Drosha or Dgcr8, in human and mouse cancer cell lines promotes transformation, generating cells that are more proliferative, invasive and have higher expression levels of K-Ras and c-Myc.92 The let7 family of miRNAs have been identified to be important in regulating the expression levels of K-Ras and c-Myc.93 Let-7 expression has been observed to be reduced in a number of cancer cell lines including breast and lung, with a corresponding upregulation in expression of Ras.94,95 In addition the overexpression of let-7 was observed to reduce the proliferation potential as well as tumorigenic capacity of cancer cells.93,95 It should be noted that ectopic expression of the proto-oncogene c-myc has a widespread repressive action on miRNA expression, by directly binding to miRNA promoter regions.86 The silencing of miRNAs that act as tumor suppressors, resulting from the upregulation of c-myc expression, is likely to be a significant contributor to cancer development.

…And Oncogenes

Although a general downregulation of miRNA expression is observed in many cancers, the upregulated expression of some miRNAs can also be directly correlated with tumor development.96 It has been noted that in a range of tumors, including ovarian, breast and melanoma, the copy number of miRNA processing components Dicer1 and Argonaute2, as well as certain miRNAs are frequently increased.97

Upregulated expression from the miR17–92 cluster is commonly seen in human B cell lymphomas, and can act as potent oncogenes.98 The miR17–92 cluster has also been shown to be overexpressed in tumors of the lung, brain and colorectal tissue.99–101 Both the E2F and c-Myc family of transcription factors have been shown to regulate expression of the miR17–92 cluster.102,103 Through auto-regulatory feedback mechanisms, the miR17–92 cluster has been shown to dampen down c-Myc mediated proliferation by targeting E2F1. Why then is the overexpression of miR17–92 oncogenic? Part of the reason appears to be due to a suppression of apoptosis.98 The proapoptotic gene BCL2-like 11 (BIM) has been identified to be a direct target of the miR17–92 cluster104–106 and likely contributes to cancer progression associated with upregulated expression from this miRNA cluster.

Overexpression of Lin28B has also been reported in 15% of human tumors and human cancer cell lines and is associated with advanced stage tumors from many cell types.107 As mentioned earlier, let-7 is a known target of Lin28, and repression of let-7 is the likely cause for the observed tumor development. An enhanced repression in the processing of mature let7 would be predicted to generate higher expression levels of proliferative factors, including c-Myc and K-Ras. Thus, it is conceivable that other components of miRNA processing and biogenesis pathway would act similarly as oncogenes when overexpressed.

Concluding Remarks

miRNAs have recently emerged from obscurity to be acknowledged as critical regulators in all cellular events, including division, differentiation and death. miRNAs generally function by repressing translation or promoting degradation of mRNA targets, generating sweeping changes in gene expression. Predictive software programmes have identified hundreds of potential targets for individual miRNAs, which has been experimentally supported. Although the key mechanisms by which miRNAs target mRNAs is well understood, it appears there is still much to learn about the intricacies of miRNA regulation. The discovery of additional factors that enhance miRNA targeting such as further cis-acting elements, will facilitate our understanding of miRNA activity and assist in the refining of such prediction programmes.

The mechanisms that maintain stem cell pluripotency and direct differentiation of their progeny are undoubtedly under the control of miRNAs. This is exemplified by the fact that cell cycle progression, expression of pluirpotency factors and the state of differentiation can be modified by expressing or removing certain miRNAs. Expression profiling studies have identified miRNAs which are specifically expressed in ESCs and appear important for maintaining pluripotency. Some of these miRNAs share a consensus seed sequence associated with cell cycle progression. Furthermore several of these miRNAs have been identified to act as oncogenes, suggesting that miRNAs provide both stem cells and cancer cells with similar proliferative properties. Although the few experimentally proven targets for these miRNAs have been shown to play fundamental roles in cell proliferation and transcriptional regulation, a more comprehensive list of verified targets will provide researchers with a greater understanding of the genetic regulation involved in stem cell identity. We believe that the mechanistic functions of some miRNAs could be applied from stem cells to cancer cells and vice-versa, and will help researchers more accurately define the properties of both cells. The ability of miRNAs to regulate target genes critical to stem cell behaviour, make an understanding of their function of critical importance to future technologies involving the manipulation of stem cells for therapy and to develop potential new miRNA-based treatments for cancer.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nicole Siddall, Shayne Bellingham and Leonie Quinn for critical reading of the manuscript. G.R.H. is funded by an NHMRC project grant and W.G.S. is a NHMRC Peter Doherty Fellow.

Abbreviations

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- B-CLL

B cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia

- BIM

BCL2-like 11

- CSCs

cancer stem cells

- cdks

cyclin-dependent kinases

- DGCR8

digeorge syndrome critical region gene 8

- ESC

embryonic stem cells

- HSC

hematopoietic stem cells

- hESC

human embryonic stem cell

- iPS

induced pluripotent stem cell

- KLF4

kruppel-like factor 4

- LRH1

liver receptor homologue 1

- miRNA

microRNA

- mESC

murine embryonic stem cell

- mirPS

miRNA induced pluripotent stem cell

- P-bodies

processing bodies

- pre-miRNA

precursor-miRNA

- pri-miRNA

primary-miRNA

- Rbl2

retinoblastoma-like 2 protein

- RISC

RNA-induced silencing complex

- Sox2

SRY-box containing gene 2

- SSEA-3

stage-specific embryonic antigen-3

- 3′UTR

3′ untranslated region

Footnotes

Previously published online as a Cell Adhesion & Migration E-publication: http://www.landesbioscience.com/journals/celladhesion/article/9913

References

- 1.Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JB, Sebastiano V, Wu G, Arauzo-Bravo MJ, Sasse P, Gentile L, et al. Oct4-induced pluripotency in adult neural stem cells. Cell. 2009;136:411–419. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bilodeau M, Sauvageau G. Uncovering stemness. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8:1048–1049. doi: 10.1038/ncb1006-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meshorer E, Misteli T. Chromatin in pluripotent embryonic stem cells and differentiation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:540–546. doi: 10.1038/nrm1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wightman B, Ha I, Ruvkun G. Posttranscriptional regulation of the heterochronic gene lin-14 by lin-4 mediates temporal pattern formation in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;75:855–862. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berezikov E, Guryev V, van de Belt J, Wienholds E, Plasterk RH, Cuppen E. Phylogenetic shadowing and computational identification of human microRNA genes. Cell. 2005;120:21–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rodriguez A, Griffiths-Jones S, Ashurst JL, Bradley A. Identification of mammalian microRNA host genes and transcription units. Genome Res. 2004;14:1902–1910. doi: 10.1101/gr.2722704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borchert GM, Lanier W, Davidson BL. RNA polymerase III transcribes human microRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:1097–1101. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee Y, Kim M, Han J, Yeom KH, Lee S, Baek SH, Kim VN. MicroRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2004;23:4051–4060. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cai X, Hagedorn CH, Cullen BR. Human microRNAs are processed from capped, polyadenylated transcripts that can also function as mRNAs. RNA. 2004;10:1957–1966. doi: 10.1261/rna.7135204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Landthaler M, Yalcin A, Tuschl T. The human DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 and Its D. melanogaster homolog are required for miRNA biogenesis. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2162–2167. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y, Ahn C, Han J, Choi H, Kim J, Yim J, et al. The nuclear RNase III Drosha initiates microRNA processing. Nature. 2003;425:415–419. doi: 10.1038/nature01957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bohnsack MT, Czaplinski K, Gorlich D. Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. RNA. 2004;10:185–191. doi: 10.1261/rna.5167604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hutvagner G, McLachlan J, Pasquinelli AE, Balint E, Tuschl T, Zamore PD. A cellular function for the RNA-interference enzyme Dicer in the maturation of the let-7 small temporal RNA. Science. 2001;293:834–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1062961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ketting RF, Fischer SE, Bernstein E, Sijen T, Hannon GJ, Plasterk RH. Dicer functions in RNA interference and in synthesis of small RNA involved in developmental timing in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2001;15:2654–2659. doi: 10.1101/gad.927801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomson JM, Newman M, Parker JS, Morin-Kensicki EM, Wright T, Hammond SM. Extensive post-transcriptional regulation of microRNAs and its implications for cancer. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2202–2207. doi: 10.1101/gad.1444406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Obernosterer G, Leuschner PJ, Alenius M, Martinez J. Post-transcriptional regulation of microRNA expression. RNA. 2006;12:1161–1167. doi: 10.1261/rna.2322506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viswanathan SR, Daley GQ, Gregory RI. Selective blockade of microRNA processing by Lin28. Science. 2008;320:97–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1154040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heo I, Joo C, Cho J, Ha M, Han J, Kim VN. Lin28 mediates the terminal uridylation of let-7 precursor MicroRNA. Mol Cell. 2008;32:276–284. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Newman MA, Thomson JM, Hammond SM. Lin-28 interaction with the Let-7 precursor loop mediates regulated microRNA processing. RNA. 2008;14:1539–1549. doi: 10.1261/rna.1155108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rybak A, Fuchs H, Smirnova L, Brandt C, Pohl EE, Nitsch R, Wulczyn FG. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:987–993. doi: 10.1038/ncb1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gregory RI, Chendrimada TP, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2005;123:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maniataki E, Mourelatos Z. A human, ATP-independent, RISC assembly machine fueled by pre-miRNA. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2979–2990. doi: 10.1101/gad.1384005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lai EC. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3′ UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nature Genet. 2002;30:363–364. doi: 10.1038/ng865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:85. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmidt T, Mewes HW, Stumpflen V. A novel putative miRNA target enhancer signal. PloS One. 2009;4:6473. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Farh KK, Grimson A, Jan C, Lewis BP, Johnston WK, Lim LP, et al. The widespread impact of mammalian MicroRNAs on mRNA repression and evolution. Science. 2005;310:1817–1821. doi: 10.1126/science.1121158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim LP, Lau NC, Garrett-Engele P, Grimson A, Schelter JM, Castle J, et al. Microarray analysis shows that some microRNAs downregulate large numbers of target mRNAs. Nature. 2005;433:769–773. doi: 10.1038/nature03315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J, Valencia-Sanchez MA, Hannon GJ, Parker R. MicroRNA-dependent localization of targeted mRNAs to mammalian P-bodies. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:719–723. doi: 10.1038/ncb1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sen GL, Blau HM. Argonaute 2/RISC resides in sites of mammalian mRNA decay known as cytoplasmic bodies. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:633–636. doi: 10.1038/ncb1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vasudevan S, Tong Y, Steitz JA. Switching from repression to activation: microRNAs can upregulate translation. Science. 2007;318:1931–1934. doi: 10.1126/science.1149460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boutz PL, Chawla G, Stoilov P, Black DL. MicroRNAs regulate the expression of the alternative splicing factor nPTB during muscle development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:71–84. doi: 10.1101/gad.1500707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Makeyev EV, Zhang J, Carrasco MA, Maniatis T. The MicroRNA miR-124 promotes neuronal differentiation by triggering brain-specific alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selbach M, Schwanhausser B, Thierfelder N, Fang Z, Khanin R, Rajewsky N. Widespread changes in protein synthesis induced by microRNAs. Nature. 2008;455:58–63. doi: 10.1038/nature07228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yu J, Wang F, Yang GH, Wang FL, Ma YN, Du ZW, Zhang JW. Human microRNA clusters: genomic organization and expression profile in leukemia cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;349:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.07.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krek A, Grun D, Poy MN, Wolf R, Rosenberg L, Epstein EJ, et al. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat Genet. 2005;37:495–500. doi: 10.1038/ng1536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lewis BP, Burge CB, Bartel DP. Conserved seed pairing, often flanked by adenosines, indicates that thousands of human genes are microRNA targets. Cell. 2005;120:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sood P, Krek A, Zavolan M, Macino G, Rajewsky N. Cell-type-specific signatures of microRNAs on target mRNA expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2746–2751. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511045103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stark A, Brennecke J, Bushati N, Russell RB, Cohen SM. Animal MicroRNAs confer robustness to gene expression and have a significant impact on 3′UTR evolution. Cell. 2005;123:1133–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krichevsky AM, King KS, Donahue CP, Khrapko K, Kosik KS. A microRNA array reveals extensive regulation of microRNAs during brain development. RNA. 2003;9:1274–1281. doi: 10.1261/rna.5980303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lagos-Quintana M, Rauhut R, Yalcin A, Meyer J, Lendeckel W, Tuschl T. Identification of tissue-specific microRNAs from mouse. Curr Biol. 2002;12:735–739. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00809-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nelson PT, Baldwin DA, Scearce LM, Oberholtzer JC, Tobias JW, Mourelatos Z. Microarray-based, high-throughput gene expression profiling of microRNAs. Nat Methods. 2004;1:155–161. doi: 10.1038/nmeth717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sempere LF, Freemantle S, Pitha-Rowe I, Moss E, Dmitrovsky E, Ambros V. Expression profiling of mammalian microRNAs uncovers a subset of brain-expressed microRNAs with possible roles in murine and human neuronal differentiation. Genome Biol. 2004;5:13. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-3-r13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Houbaviy HB, Murray MF, Sharp PA. Embryonic stem cell-specific MicroRNAs. Dev Cell. 2003;5:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00227-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Suh MR, Lee Y, Kim JY, Kim SK, Moon SH, Lee JY, et al. Human embryonic stem cells express a unique set of microRNAs. Dev Biol. 2004;270:488–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Calabrese JM, Seila AC, Yeo GW, Sharp PA. RNA sequence analysis defines Dicer's role in mouse embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18097–18102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709193104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marson A, Levine SS, Cole MF, Frampton GM, Brambrink T, Johnstone S, et al. Connecting microRNA genes to the core transcriptional regulatory circuitry of embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;134:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laurent LC, Chen J, Ulitsky I, Mueller FJ, Lu C, Shamir R, et al. Comprehensive microRNA profiling reveals a unique human embryonic stem cell signature dominated by a single seed sequence. Stem cells. 2008;26:1506–1516. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Strauss WM, Chen C, Lee CT, Ridzon D. Nonrestrictive developmental regulation of microRNA gene expression. Mamm Genome. 2006;17:833–840. doi: 10.1007/s00335-006-0025-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yuan A, Farber EL, Rapoport AL, Tejada D, Deniskin R, Akhmedov NB, Farber DB. Transfer of microRNAs by embryonic stem cell microvesicles. PloS One. 2009;4:4722. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, et al. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet. 2003;35:215–217. doi: 10.1038/ng1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murchison EP, Partridge JF, Tam OH, Cheloufi S, Hannon GJ. Characterization of Dicer-deficient murine embryonic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:12135–12140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505479102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kanellopoulou C, Muljo SA, Kung AL, Ganesan S, Drapkin R, Jenuwein T, et al. Dicer-deficient mouse embryonic stem cells are defective in differentiation and centromeric silencing. Genes Dev. 2005;19:489–501. doi: 10.1101/gad.1248505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Y, Medvid R, Melton C, Jaenisch R, Blelloch R. DGCR8 is essential for microRNA biogenesis and silencing of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nat Genet. 2007;39:380–385. doi: 10.1038/ng1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ben-Shushan E, Pikarsky E, Klar A, Bergman Y. Extinction of Oct-3/4 gene expression in embryonal carcinoma x fibroblast somatic cell hybrids is accompanied by changes in the methylation status, chromatin structure and transcriptional activity of the Oct-3/4 upstream region. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:891–901. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.2.891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Benetti R, Gonzalo S, Jaco I, Munoz P, Gonzalez S, Schoeftner S, et al. A mammalian microRNA cluster controls DNA methylation and telomere recombination via Rbl2-dependent regulation of DNA methyltransferases. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:268–279. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sinkkonen L, Hugenschmidt T, Berninger P, Gaidatzis D, Mohn F, Artus-Revel CG, et al. MicroRNAs control de novo DNA methylation through regulation of transcriptional repressors in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:259–267. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G, Thomson JA, Kosik KS. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2 and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137:647–658. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tay Y, Zhang J, Thomson AM, Lim B, Rigoutsos I. MicroRNAs to Nanog, Oct4 and Sox2 coding regions modulate embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nature. 2008;455:1124–1128. doi: 10.1038/nature07299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okita K, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Generation of germline-competent induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature. 2007;448:313–317. doi: 10.1038/nature05934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Judson RL, Babiarz JE, Venere M, Blelloch R. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs promote induced pluripotency. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:459–461. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu J, Vodyanik MA, Smuga-Otto K, Antosiewicz-Bourget J, Frane JL, Tian S, et al. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science. 2007;318:1917–1920. doi: 10.1126/science.1151526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lin SL, Chang DC, Chang-Lin S, Lin CH, Wu DT, Chen DT, Ying SY. Mir-302 reprograms human skin cancer cells into a pluripotent ES-cell-like state. RNA. 2008;14:2115–2124. doi: 10.1261/rna.1162708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andl T, Murchison EP, Liu F, Zhang Y, Yunta-Gonzalez M, Tobias JW, et al. The miRNA-processing enzyme dicer is essential for the morphogenesis and maintenance of hair follicles. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1041–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cheng LC, Pastrana E, Tavazoie M, Doetsch F. miR-124 regulates adult neurogenesis in the subventricular zone stem cell niche. Nature Neurosci. 2009;12:399–408. doi: 10.1038/nn.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Savatier P, Huang S, Szekely L, Wiman KG, Samarut J. Contrasting patterns of retinoblastoma protein expression in mouse embryonic stem cells and embryonic fibroblasts. Oncogene. 1994;9:809–818. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wang Y, Baskerville S, Shenoy A, Babiarz JE, Baehner L, Blelloch R. Embryonic stem cell-specific microRNAs regulate the G1-S transition and promote rapid proliferation. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1478–1483. doi: 10.1038/ng.250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Card DA, Hebbar PB, Li L, Trotter KW, Komatsu Y, Mishina Y, Archer TK. Oct4/Sox2-regulated miR-302 targets cyclin D1 in human embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:6426–6438. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00359-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee NS, Kim JS, Cho WJ, Lee MR, Steiner R, Gompers A, et al. miR-302b maintains “stemness” of human embryonal carcinoma cells by post-transcriptional regulation of Cyclin D2 expression. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;377:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sengupta S, Nie J, Wagner RJ, Yang C, Stewart R, Thomson JA. MicroRNA 92b Controls the G1/S Checkpoint Gene p57 in Human Embryonic Stem Cells. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1524–1528. doi: 10.1002/stem.84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sperger JM, Chen X, Draper JS, Antosiewicz JE, Chon CH, Jones SB, et al. Gene expression patterns in human embryonic stem cells and human pluripotent germ cell tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13350–13355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235735100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y, Blelloch R. Cell cycle regulation by MicroRNAs in embryonic stem cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4093–4096. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-0309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Shimono Y, Zabala M, Cho RW, Lobo N, Dalerba P, Qian D, et al. Downregulation of miRNA-200c Links Breast Cancer Stem Cells with Normal Stem Cells. Cell. 2009;138:592–603. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3:730–737. doi: 10.1038/nm0797-730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Woodward WA, Chen MS, Behbod F, Alfaro MP, Buchholz TA, Rosen JM. WNT/beta-catenin mediates radiation resistance of mouse mammary progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:618–623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606599104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wulf GG, Wang RY, Kuehnle I, Weidner D, Marini F, Brenner MK, et al. A leukemic stem cell with intrinsic drug efflux capacity in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2001;98:1166–1173. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.4.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lapidot T, Sirard C, Vormoor J, Murdoch B, Hoang T, Caceres-Cortes J, et al. A cell initiating human acute myeloid leukaemia after transplantation into SCID mice. Nature. 1994;367:645–648. doi: 10.1038/367645a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kelly PN, Dakic A, Adams JM, Nutt SL, Strasser A. Tumor growth need not be driven by rare cancer stem cells. Science. 2007;317:337. doi: 10.1126/science.1142596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Quintana E, Shackleton M, Sabel MS, Fullen DR, Johnson TM, Morrison SJ. Efficient tumour formation by single human melanoma cells. Nature. 2008;456:593–598. doi: 10.1038/nature07567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH, van de Wetering M, Begthel H, van den Born M, et al. Crypt stem cells as the cells-of-origin of intestinal cancer. Nature. 2009;457:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature07602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Chang TC, Yu D, Lee YS, Wentzel EA, Arking DE, West KM, et al. Widespread microRNA repression by Myc contributes to tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2008;40:43–50. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lu J, Getz G, Miska EA, Alvarez-Saavedra E, Lamb J, Peck D, et al. MicroRNA expression profiles classify human cancers. Nature. 2005;435:834–838. doi: 10.1038/nature03702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ozen M, Creighton CJ, Ozdemir M, Ittmann M. Widespread deregulation of microRNA expression in human prostate cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:1788–1793. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Calin GA, Sevignani C, Dumitru CD, Hyslop T, Noch E, Yendamuri S, et al. Human microRNA genes are frequently located at fragile sites and genomic regions involved in cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2999–3004. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307323101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Calin GA, Dumitru CD, Shimizu M, Bichi R, Zupo S, Noch E, et al. Frequent deletions and downregulation of micro-RNA genes miR15 and miR16 at 13q14 in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:15524–15529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.242606799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Cimmino A, Calin GA, Fabbri M, Iorio MV, Ferracin M, Shimizu M, et al. miR-15 and miR-16 induce apoptosis by targeting BCL2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13944–13949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506654102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kumar MS, Lu J, Mercer KL, Golub TR, Jacks T. Impaired microRNA processing enhances cellular transformation and tumorigenesis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:673–677. doi: 10.1038/ng2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kumar MS, Erkeland SJ, Pester RE, Chen CY, Ebert MS, Sharp PA, Jacks T. Suppression of non-small cell lung tumor development by the let-7 microRNA family. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3903–3908. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712321105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Johnson SM, Grosshans H, Shingara J, Byrom M, Jarvis R, Cheng A, et al. RAS is regulated by the let-7 microRNA family. Cell. 2005;120:635–647. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yu F, Yao H, Zhu P, Zhang X, Pan Q, Gong C, et al. let-7 regulates self renewal and tumorigenicity of breast cancer cells. Cell. 2007;131:1109–1123. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Volinia S, Calin GA, Liu CG, Ambs S, Cimmino A, Petrocca F, et al. A microRNA expression signature of human solid tumors defines cancer gene targets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2257–2261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510565103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Zhang L, Huang J, Yang N, Greshock J, Megraw MS, Giannakakis A, et al. microRNAs exhibit high frequency genomic alterations in human cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9136–9141. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508889103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.He L, Thomson JM, Hemann MT, Hernando-Monge E, Mu D, Goodson S, et al. A microRNA polycistron as a potential human oncogene. Nature. 2005;435:828–833. doi: 10.1038/nature03552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hayashita Y, Osada H, Tatematsu Y, Yamada H, Yanagisawa K, Tomida S, et al. A polycistronic microRNA cluster, miR-17-92, is overexpressed in human lung cancers and enhances cell proliferation. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9628–9632. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Motoyama K, Inoue H, Takatsuno Y, Tanaka F, Mimori K, Uetake H, et al. Over- and under-expressed microRNAs in human colorectal cancer. Int J Oncol. 2009;34:1069–1075. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Northcott PA, Fernandez LA, Hagan JP, Ellison DW, Grajkowska W, Gillespie Y, et al. The miR-17/92 polycistron is upregulated in sonic hedgehog-driven medulloblastomas and induced by N-myc in sonic hedgehog-treated cerebellar neural precursors. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3249–3255. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.O'Donnell KA, Wentzel EA, Zeller KI, Dang CV, Mendell JT. c-Myc-regulated microRNAs modulate E2F1 expression. Nature. 2005;435:839–843. doi: 10.1038/nature03677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Woods K, Thomson JM, Hammond SM. Direct regulation of an oncogenic micro-RNA cluster by E2F transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2007;8:2130–2134. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600252200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Koralov SB, Muljo SA, Galler GR, Krek A, Chakraborty T, Kanellopoulou C, et al. Dicer ablation affects antibody diversity and cell survival in the B lymphocyte lineage. Cell. 2008;132:860–874. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Ventura A, Young AG, Winslow MM, Lintault L, Meissner A, Erkeland SJ, et al. Targeted deletion reveals essential and overlapping functions of the miR-17 through 92 family of miRNA clusters. Cell. 2008;132:875–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Xiao C, Srinivasan L, Calado DP, Patterson HC, Zhang B, Wang J, et al. Lymphoproliferative disease and autoimmunity in mice with increased miR-17-92 expression in lymphocytes. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:405–414. doi: 10.1038/ni1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Viswanathan SR, Powers JT, Einhorn W, Hoshida Y, Ng TL, Toffanin S, et al. Lin28 promotes transformation and is associated with advanced human malignancies. Nat Genet. 2009;41:843–848. doi: 10.1038/ng.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]