Abstract

Background and Aims

The influence of two nitrogen (N) levels on growth, water relations, and N uptake and flow was investigated in two different inbred lines of maize (N-efficient Zi330 and N-inefficient Chen94-11) to analyse the differences in N uptake and cycling within a plant.

Methods

Xylem sap from different leaves of the inbred lines cultured in quartz sand was collected by application of pressure to the root system. Plant transpiration was measured on a daily basis by weighing five pots of each of the treatments.

Key Results

N-efficient Zi330 had a higher relative growth rate and water-use efficiency at both high (4 mm) and low (0·08 mm) N levels. At a high N level, the amount of N taken up was similar for the two inbred lines; the amount of N transported in the xylem and retranslocated in the phloem was slight greater in Chen94-11 than in Zi330. At a low N level, however, the total amount of N taken up, transported in the xylem and retranslocated in the phloem of Zi330 was 2·2, 2·7 and 2·7 times more, respectively, than that of Chen94-11. Independent of inbred line and N level, the amounts of N transported in the xylem and cycled in the phloem were far more than that taken up by roots at the same time. Low N supply shifted NO3−1 reduction towards the roots. The major nitrogenous compound in the xylem sap was NO3−1, when plants grew at the high N level, while amino acid-N was predominant when plants grew at the low N level.

Conclusions

The N-efficient maize inbred line Zi330 had a higher ability to take up N and cycle N within the plant than N-inefficient Chen94-11 when grown under N-deficiency.

Key words: Nitrogen flow, nitrogen supply, nitrogen uptake, nitrogen use efficiency, transpiration, Zea mays

INTRODUCTION

Limited nitrogen (N) supply causes reduced plant growth and morphological changes such as increased root growth relative to shoot growth to explore a larger soil volume. Another adaptive mechanism to N deficiency is making better use of the absorbed N within the plant (Marschner, 1995). At sufficient N supply in the field, variation in N-use efficiency (NUE, defined as grain production per unit of N available in the soil) is due largely to a difference in N uptake efficiency, whereas at deficient N supply, that is mainly due to a difference in utilization of accumulated N (Moll et al., 1982). It is concluded that increases in grain yield are not due to additional enhancement in inorganic N assimilation, but to a better NUE as a result of more efficient N remobilization (Hirel et al., 2001). However, it is unknown whether efficiency in whole life of the plant consistently represents the efficiency defined at the seedling or early growth stage.

Cycling of mineral nutrients, i.e. retranslocation in the phloem from shoot to roots, and translocation of cycled nutrients back to the shoot in the xylem, is important for plant growth, especially under stressed conditions (Marschner et al., 1997). Cycling of minerals (N, P, K and S) and carbon compounds between roots and shoot have convincingly been demonstrated (Lambers et al., 1982; Simpson et al., 1983; Jeschke and Pate, 1991a, b; Peuke and Jeschke, 1993; Ericsson, 1995; Jiang et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2005). Nitrogen transport and partitioning within plants vary among species [e.g. wheat (Lambers et al., 1982; Simpson et al., 1983), tobacco (Rufty et al., 1990), pea (Duarte and Larsson, 1993), castor bean (Peuke et al., 1994)] and environmental conditions [salt-stress (Jeschke and Pate, 1991b), low N status (Peuke et al., 1994), N source (Peuke and Jeschke, 1993)]. Enhanced N retranslocation from shoot to roots under lower N supply has been reported in some species [e.g. wheat (Lambers et al., 1982), tobacco (Rufty et al., 1990), pea (Duarte and Larsson, 1993), castor bean (Peuke et al., 1994)].

Nutrient levels may influence water-use efficiency (WUE, presented as net increase in plant dry weight per unit water used) of plants. In winter oil-seed rape (Brück et al., 2001) and sweet potato plants (Kelm et al., 2001), a lower N level led to lower WUE, since N stress led to increased transpiration per unit leaf area (Kelm et al., 2001). On the other hand, the dual-affinity nitrate transporter gene AtNRT1·1 (CHL1) is expressed not only in roots, but also in guard cells of Arabidopsis plants. CHL1 supports stomatal function in the presence of NO3− (Guo et al., 2003). The results suggest that NO3− plays a role in stomatal opening, since the stomatal aperture and transpiration will be reduced in the absence of NO3−.

Two maize inbred lines Zi330 (N-efficient) and Chen94-11 (N-inefficient) have been selected from >200 inbred lines in the field experiments under high (225 kg ha−1) and low (0 kg ha−1) N supply in two sites in Beijing for 2 years (Chen, 2001). The two inbred lines were fast senescent lines (compared with stay-green lines), and matured almost at the same time (Zi330 matured even 3–4 d earlier than Chen94-11). The differences in N flow in the N-efficient and N-inefficient maize inbred lines, and the extent to which translocation in the xylem and circulation of N are altered by the supply of different N levels are not clear. The present experiments were carried out to address these questions, and aimed to investigate the influence of N levels on growth, water relations, and N uptake and flow in the two maize inbred lines, to elucidate the correlations of N cycling and NUE (defined as biomass production on the basis of plant N), and to better understand the underlying mechanisms of the differences in NUE between the maize inbred lines.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant culture and growth conditions

The NUE (defined as grain production per unit of N available in the soil) of Zi330 and Chen94-11 was shown in Table 1. Maize seeds (Zea mays L.) of two inbred lines (Zi330 and Chen94-11) were surface-sterilized in 10 % H2O2 solution for 30 min and washed in running tap water. Then the seeds were germinated between filter papers moistened with a saturated CaSO4 solution for 2 d before being transferred to quartz sand watered with a saturated CaSO4 solution. Afterwards, the endosperm from selected uniform seedlings in the two-leaf stage was cut off, and seedlings were transferred to 2·1-L pots (one plant per pot) containing quartz sand (0·25–0·5 mm in diameter). The plants were watered initially with a half-strength nutrient solution. After 1 week a full-strength solution was provided. The full-strength nutrient solution had the following composition (mm): K2SO4 0·75, KCl 0·1, KH2PO4 0·25, MgSO4 0·65, Ca(NO3)2 2·0, H3BO3 1×10−3, ZnSO4 1·0×10−3, CuSO4 1·0×10−3, MnSO4 1·0×10−3, Fe-EDTA 0·15, (NH4)6Mo7O24 5·0×10−6. The initial pH of the nutrient solution was adjusted to 6·0. The plants were watered every other day (every day during the treatments) in the morning with an excess of the nutrient solution, small holes in the bottom of the pot allowing drainage. The plants were grown under controlled conditions with a light/dark regime of 14/10 h, air temperature of 28 °C/18 °C, relative humidity of 45–55 %. The photosynthetically active radiation at the surface of the pot was 220–270 µmol m−2 s−1 provided by reflector sunlight metal halide lamps (250 W; Philip Hpiplus, Belgium).

Table 1.

Nitrogen use efficiency (NUE, grain production per unit of N available in the soil, kg kg−1) of maize inbred lines Zi330 and Chen94-11 grown under the HN (225 kg ha−1) and LN (0 kg ha−1) treatments in the field in 2 years

| Year | HN |

LN |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zi330 | Chen94-11 | Zi330 | Chen94-11 | |

| 1999 | 12·4 | 4·8 | 85·0 | 38·5 |

| 2000 | 16·3 | 10·4 | 43·7 | 32·4 |

The total N and 0·01 M CaCl2 extracted mineral N (Nmin, the sum of NH4+-N and NO3−-N in the soil) of the 0–30 cm soil layer were 0·067 % and 31·79 kg ha−1 in the first site in 1999, and 0·097 % and 106·98 kg ha−1 in the second site in 2000, respectively.

Treatments and harvest procedures

The plants of each maize inbred line were divided into three groups of five plants, each of similar size and development. One group of each inbred line was used for the first harvest, the remaining two groups for the second harvest. The first harvest was made 36 d after germination when plants were in the ninth leaf expanding stage. Before the first harvest, a single N regime (4 mm) was used. On the day of the first harvest, the remaining two groups of each inbred line were treated with either 4 mm N [high N (HN) level] or 0·08 mm N [low N (LN) level) as Ca(NO3)2. The shortage of Ca in the LN treatment was compensated by adding CaCl2. The rest of the composition of the nutrient solution was the same as mentioned above. The second harvest was performed 10 d later.

Plant leaves were numbered in ascending order, starting with the lowest matured leaf, which was designed as leaf 1. At the first harvest, the youngest unfolded leaf was no. 9. At harvest, plants were separated into roots, lower leaves (1–6), middle leaves (7–8) and upper leaves (no. 9 and other newly formed leaves at the second harvest). The leaf sheath was included with each leaf. Roots were washed free of sand with tap water. All plant parts were killed at 105 °C for 30 min, dried at 70 °C to constant weight, weighed (dry weight) and ground into powder. Appropriate amounts of the ground plant material were used to determine the total N content by a modified Kjeldahl digestion method that included reduction of nitrate (Nelson and Somers, 1973). Calcium in the tissue was analysed using a flame spectrophotometer (Cole-Parmer 2655-00).

Measurement of transpiration

Whole-shoot transpiration was measured on a daily basis by weighing five pots of each of the treatments at the beginning of the light period, after the daily addition of nutrient solution and draining, and at the end of the light period (0800 h, 1000 h and 2200 h, respectively). Because of the daily addition of nutrient solution and draining between 0800 h and 1000 h, the transpiration during this time was calculated by averaging the amount of transpiration between 1000 h and 2200 h. Corrections were made for water loss from pots without plants. In all cases, evaporation from the pots was minimized by covering the exposed surface with a layer of plastic film. The values of evaporation from the pots without plants were 2·8–2·9 g d−1 during the study period. This value accounted for 4·6–7·6 % of the water losses through transpiration by plants on the first day, and 2·8–4·6 % on the last day of the study period.

Collection of xylem sap

For collection of xylem sap, the plant was grown in a steel pot with a lid, which is designed to seal the plant shoot, and allows insertion of the pot into a pressure chamber in order to apply pressure to the root system. The pot had the same size and volume as that for a plant harvest. The xylem sap-collection procedure was essentially the same as described by Jeschke and Pate (1991a). A major advantage of this technique is that the composition of the sap collected reflects that in an intact plant as many of the phloem tubes are uncut, and hence the normal cycle of solutes from shoot to root can proceed (Seel and Jeschke, 1999). Samples were taken from leaf numbers 5, 7 and 9 (counting up from the base).The xylem sap collection was repeated three times during the study period, e.g. on the second, fifth and eighth day after commencement of the treatments. In brief, at the adaxial part along the length of the leaf an incision was made into the midrib. The cut surface was carefully washed with distilled water and a Teflon tube attached. Pressure was applied to both the sand substrate and roots of the treated plants. After slowly applying pressure, xylem sap started to exude from the midrib after reaching a balancing pressure (Seel and Jeschke, 1999), and the sap was collected at 100 kPa above this pressure. The recorded balancing pressures for xylem sap collections from leaves of two maize inbred lines grown under supply of 0·08 or 4 mm N are shown in Table 2. The first exudate was discarded to avoid contamination from cut cells. Xylem sap was kept on ice during collection and stored at −20 °C before analyses. Calcium in the xylem sap was analysed directly after appropriate dilution using ICP (Perkin Elmer 3300 DV, USA). Nitrate and ammonium in the xylem sap were analysed by a TRAACS-2000 autoanalyser (Bran+Luebee, Germany). Amino acids in the xylem sap were determined using an amino acid autoanalyser (Hitachi 8800). The total N in the xylem sap was assumed to be the sum of NO3−-N, NH4+-N and amino acid-N.

Table 2.

The recorded balancing pressures (kPa) for xylem sap collections from leaves of two maize inbred lines grown under HN (4 mm) and LN (0·08 mm) conditions

| Sampling times | Zi330 |

Chen94-11 |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN | LN | HN | LN | |

| 1 | 390 | 390 | 280 | 320 |

| 2 | 340 | 350 | 360 | 400 |

| 3 | 340 | 290 | 390 | 380 |

Samples were taken from leaf numbers 5, 7 and 9 (counting up from the base).The xylem sap collection was repeated three times during the study period, e.g. on the second, fifth and eighth day after commencement of the treatments.

Estimation of the net flows of N through xylem and phloem in the whole plant

Net flows of N in plants were estimated using the method described by Armstrong and Kirkby (1979). The assumption of the model was that nutrients were transported solely through xylem and phloem, Ca2+ could only be transported apically through the xylem and had no mobility in the phloem.

The net xylem flows of Ca2+, JCa,x, transported to various plant parts during a given period was the same as the net increment of Ca2+, ΔCa, in the same position during the same phase, where

|

In relatively stable growth conditions, the N : Ca ratio in xylem sap, [N/Ca]x, delivered to individual organs was constant, and these values were derived from the concentration of N and Ca in the collected xylem sap.

For a given period, the net xylem flow of N, JN,x, toward a site was calculated from the net increment of Ca2+, ΔCa, and the N : Ca ratio, [N/Ca]x, in the xylem sap by:

The amount of N exported through the phloem, JN,p, was equal to the difference between the measured N increment, ΔN, in each organ and the net xylem import according to:

|

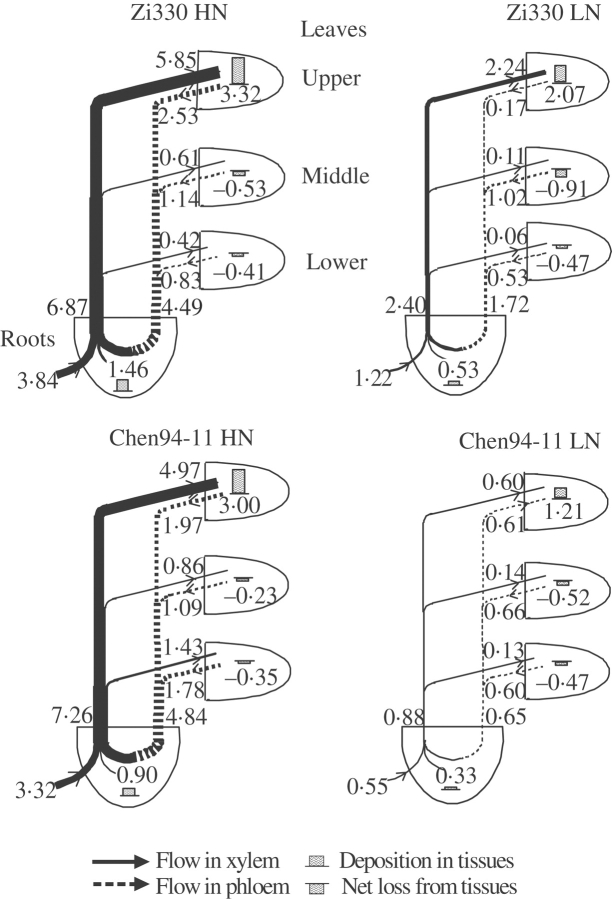

A positive difference indicates net phloem import, while a negative difference implies net phloem export from an organ. Working progressively along the plant from the root to the leaves, the net flows of N within a whole plant were obtained (as shown in Fig. 2). The differences between the quantities of N translocated in the phloem and in the xylem then also allowed the transfer processes between these translocation streams to be estimated.

Fig. 2.

Flow profiles for uptake, transport and utilization of N in two maize inbred lines supplied with high (4 mm, HN) or low (0·08 mm, LN) levels of nitrate over a 10-d study period. The values of N deposition and the statistical significance are given in Table 5. The width of lines and the height of histograms are drawn in proportion to the net flows and deposition of N. The numbers indicate the values of uptake, transport and utilization (mmol N plant−1 over the 10-d study period).

Statistical treatment

Dry weight and total N increments were obtained from five replicates of each treatment at the first and the second harvest. All further analyses were made with five individual samples for each organ. For statistical analysis of the data, the program SAS for windows (version 6·12) was used (SAS, 1987). Differences between data in all tables were tested with one-way (initial value) and two-way (net increment in the second harvest) analysis of variance (ANOVA).

RESULTS

Plant growth and development

At the first harvest, the dry weight (d. wt) of whole plants and individual organs, except the lower leaves of the N-inefficient inbred line Chen94-11, was already lower than that of the N-efficient Zi330 (Table 3). After 10-d growth at 0·08 mm N, all plants of both inbred lines showed symptoms of N deficiency, such as senesced lower leaves and small plant size compared with those grown at 4 mm N. In comparison, the net d. wt gain of the upper leaves of Chen94-11 at the LN level was less than that of Zi330. There was even a decrease in d. wt of the lower leaves in both lines. Growth at the HN level resulted in a greater net d. wt gain, including lower leaves. At both N levels the upper leaves and roots contributed most to the dry matter gain in both lines.

Table 3.

Root : shoot dry weight ratio, initial values and net increments in dry weight of the component organs and of the whole maize plant (N-efficient inbred line Zi330 and N-inefficient inbred line Chen94-11) grown at the HN (4 mm) and LN levels (0·08 mm) over a 10-d study period

| Treatment | Maize inbred lines | Dry weight (d. wt g−1 organ plant−1) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper leaves | Middle leaves | Lower leaves | Roots | Whole plant | Root/shoot ratio | ||

| Initial dry weight | |||||||

| Zi330 | 0·68a | 0·74a | 0·40b | 0·36a | 2·18a | 0·20a | |

| Chen94-11 | 0·33b | 0·64a | 0·52a | 0·25b | 1·74b | 0·17a | |

| Net increments at the second harvest | |||||||

| HN | Zi330 | 3·68a | 0·24a* | 0·03a* | 1·44a | 5·38a | 0·31a |

| Chen94-11 | 2·57a* | 0·28a* | 0·05a* | 0·72b | 3·63b* | 0·22b* | |

| LN | Zi330 | 3·63a | 0·04b | −0·07a | 1·15a | 4·75a | 0·28a |

| Chen 94–11 | 1·65b | 0·10b | −0·08a | 0·63b | 2·30b | 0·28a | |

Values in columns followed by the same letter of initial values and the second harvest between two maize inbred lines under same N level are not significantly different at P≤0·05.

*Difference between the HN and LN treatments significant at P≤0·05 for the same maize inbred lines.

The difference in interaction between N level and maize inbred lines was not significant.

Total transpiration and water-use efficiency

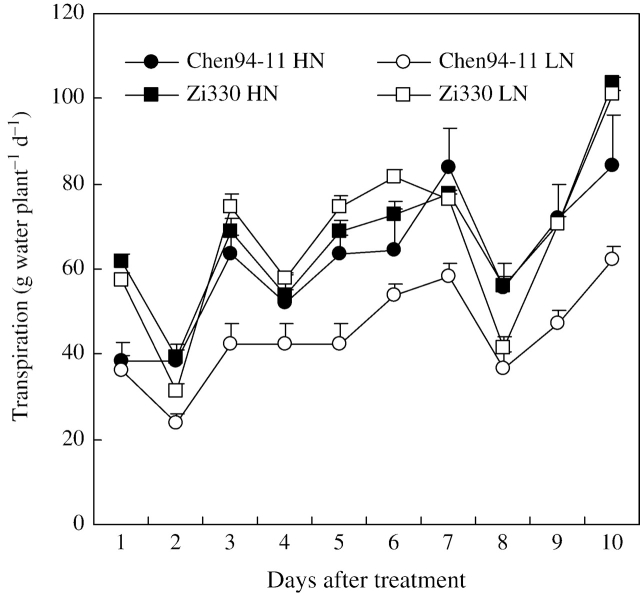

At the first harvest, the N-efficient Zi330 had a larger shoot d. wt and leaf area than that of the N-inefficient Chen94-11 (Table 3), and also a higher daily shoot transpiration rate (Fig. 1). In comparison with the HN treatment, the LN treatment did not influence daily shoot transpiration of Zi330, while that of Chen94-11 was strongly reduced.

Fig. 1.

Time-course of whole-plant transpiration of two maize inbred lines as dependent on N levels (LN=0·08 mm, HN=4 mm). Bars denote s.e.m., n=5.

Zi330 had a higher WUE than Chen94-11 at both N levels. Decreasing N supply had no influence on WUE in both inbred lines (Table 4).

Table 4.

Water-use efficiency (g total plant d. wt increase kg−1 H2O) of whole maize plant (N-efficient inbred line Zi330 and N-inefficient inbred line Chen94-11) grown at the HN (4 mm) and LN levels (0·08 mm) over a 10-d study period

| HN |

LN |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zi330 | Chen94-11 | Zi330 | Chen94-11 | |

| WUE | 7·95±0·47a | 5·87±0·41b | 7·12±0·63a | 5·16±0·34b |

Values in row followed by the different letter are significantly different between the two maize inbred lines at P≤0·05.

Changes in tissue N contents

The changes in net N increment as affected by two N levels were similar to that in net dry matter gain. At the first harvest, the total N content in Zi330 was higher than that in Chen94-11 (Table 5). After 10 d growth at the same N level (HN, 4 mm), the total net N increment in both inbred lines was not significantly different. At the LN level, however, the total net N increment in both inbred lines was markedly reduced, and that in Chen94-11 was more suppressed than in Zi330. In all cases, the greatest increment of N was found in the rapidly growing organs, i.e. upper leaves and roots, while net N export from the middle and lower leaves in both inbred lines was observed, no matter whether HN or LN was supplied.

Table 5.

Initial values and net increments in N contents of the component organs and of the whole maize plant grown at the HN (4 mm) and LN levels (0·08 mm) over a 10-d study period

| Treatments | Maize inbred lines | N content (mmol per organ/plant) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Upper leaves | Middle leaves | Lower leaves | Roots | Whole plant | ||

| Initial value | ||||||

| Zi330 | 1·32a | 1·39a | 0·66a | 0·42a | 3·79a | |

| Chen94-11 | 0·61b | 1·22a | 0·84a | 0·33a | 3·00b | |

| Net increments at the second harvest | ||||||

| HN | Zi330 | 3·32a* | −0·53b* | −0·41a* | 1·46a* | 3·84a* |

| Chen94-11 | 3·00a* | −0·23a* | −0·35a* | 0·90b* | 3·32a* | |

| LN | Zi330 | 2·07a | −0·91b | −0·47a | 0·53a | 1·22a |

| Chen94-11 | 1·21b | −0·52a | −0·47a | 0·33b | 0·55b | |

Values in columns followed by the same letter of initial values and the second harvest between two maize inbred lines under same N level are not significantly different at P≤0·05.

*Difference between the HN and LN treatments significant at P≤0·05 for the same maize inbred lines.

The difference in interaction between N level and maize inbred lines was not significant.

Nitrogenous compounds in xylem sap

The changes in total N concentration and percentage of different nitrogenous compounds to total N in the xylem sap of different leaves of two maize inbred lines grown at both N levels showed similar patterns (Table 6). Total N concentration was higher, and the major nitrogenous compound was NO3−, when plants grew at the HN level. Total N concentration was lower, and the majority of nitrogenous compounds was in the form of amino acid-N, when the plants were grown at the LN level. In comparison, total N concentration in the xylem sap of different leaves of Zi330 grown under both N levels increased from lower leaves to the upper leaves. By contrast, that in Chen94-11 decreased from lower leaves to the upper leaves, especially when the plants were grown at the HN level (Table 6).

Table 6.

Concentrations of different nitrogen forms and total N (mm) in the xylem sap of different leaves of two maize inbred lines grown at the HN (4 mm) and LN (0·08 mm) levels over a 10-d study period

| Upper leaves |

Middle leaves |

Lower leaves |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HN |

LN |

HN |

LN |

HN |

LN |

|||||||

| Zi330 | Chen94-11 | Zi330 | Chen94-11 | Zi330 | Chen94-11 | Zi330 | Chen94-11 | Zi330 | Chen94-11 | Zi330 | Chen94-11 | |

| NO3−-N | 5·71a*(85·1) | 1·18b*(76·6) | 0·23a(28·9) | 0·14a(35·3) | 3·52a*(73·6) | 2·64a*(73·2) | 0·18a(25·5) | 0·31a(41·4) | 2·96a*(81·4) | 4·01a*(79·5) | 0·16a(39·6) | 0·34a(54·3) |

| NH4+-N | 0·06a(0·8) | 0·05a(3·2) | 0·03a(3·4) | 0·03a(7·3) | 0·03a(0·6) | 0·04a(1·1) | 0·03a(4·1) | 0·01a(2·0) | 0·02a(0·7) | 0·08a(1·5) | 0·02a(5·0) | 0·03a(5·2) |

| Amino-N | 0·94a(14·1) | 0·31a(20·2) | 0·53a(66·7) | 0·24a(57·4) | 1·23a*(25·8) | 0·93a(25·7) | 0·50a(70·4) | 0·42a(56·6) | 0·65a(17·9) | 0·95*a(19·0) | 0·23a(55·4) | 0·26a(40·5) |

| Total N | 6·71a* | 1·54b* | 0·79a | 0·41a | 4·78a* | 3·61a* | 0·71a | 0·74a | 3·64b* | 5·04a* | 0·41a | 0·63a |

The values in parentheses indicate the proportion of different nitrogen forms to total N measured in the xylem sap.

Values in rows between two maize inbred lines under the same N level of the same leaf stratum followed by the same letter are not significantly different at P≤0·05.

*Difference between the HN and LN treatments significant at P≤0·05 for the same maize inbred lines.

Estimation of net N flow within plants

In all cases, the largest sink for N deposition was the upper leaves, which accounted for 86 %, 170 %, 90 % and 220 % of the total N taken up in Zi330-HN, Zi330-LN, Chen94-11-HN and Chen94-11-LN, respectively (Fig. 2). Since the amount of nitrogenous compounds transported in the xylem, which equalled the sum of N imported into different leaves, exceeded the total N uptake, phloem retranslocation of N from shoot to roots contributed to the N transported in the xylem. The amount of N retranslocated in the phloem in all cases was more than that of the total uptake, and contributed to 65 % and 67 % of N transported in the xylem of Zi330 and Chen94-11 grown at the HN level, and 72 % and 74 % at the LN level, respectively.

The phloem-recycled N from shoot to roots came from different leaves (Fig. 2). Even net N export from the middle and lower leaves took place in both inbred lines grown at both N levels, since the N exported via the phloem exceeded the N imported via xylem in these leaves.

DISCUSSION

Effects on plant growth and N uptake

Already at the first harvest, the whole plant d. wt and N content of the N-efficient Zi330 was significantly higher than that of the N-inefficient Chen94-11, indicating that the former had a larger relative growth rate and a higher N uptake ability than the later (Tables 3 and 5). In comparison with growth at the HN level, decreasing N supply (0·08 mm) during the 10-d study period reduced total net d. wt gain and especially total net N increment in both inbred lines, in which the reduction in Chen94-11 was more dramatic. In spite of this, the net dry matter gain of the upper leaves of Zi330 was not changed, while that of Chen94-11 was reduced markedly. The results indicate that Zi330 was more efficient in N uptake and building up new tissues, especially when grown at the LN level. This was confirmed by root N uptake rate expressed as per unit root dry weight. The root N uptake rate (mm g−1 d. wt root 10 d−1) of Zi330 and Chen94 was 2·05 and 3·57 when grown under the HN level, and 0·80 and 0·70 when grown under the LN level, respectively (calculation based on the results in Tables 3 and 5). The NUE (defined as biomass production on the basis of plant N) of Zi330 and Chen94-11 in the present study was 71 and 61 at the HN level, and 99 and 81 at the LN level, respectively. This agreed with the results of the field experiments (Table 1). The results indicated that both NUE values, i.e. defined as grain production per unit of the soil-available N in the field experiment (Table 1) and as plant biomass production at an early growth stage on the basis of plant N in the present study, respectively, were consistent for both maize inbred lines.

Transpiration and water-use efficiency

Reducing N supply in the growth medium did not influence daily shoot transpiration of Zi330, while that of Chen94-11 was markedly reduced (Fig. 1). This was related to the differences in the net dry matter gain of the upper leaves of both inbred lines (Table 3). The WUE of Zi330 was higher than that of Chen94-11 at both N levels (Table 4). This could be explained by the difference in transpiration rate. On leaf dry weight basis at the second harvest, the transpiration rate of Zi330 and Chen94-11 was 11·8 and 14·1 g g−1 d−1 leaf dry weight under the HN treatment, and 12·3 and 14·1 g g−1 d−1 leaf dry weight under the LN treatment, respectively (calculation based on the results in Table 3 and Fig. 1). It was clear that the transpiration rate of Chen94-11 on a leaf dry weight basis was higher than that of Zi330 under both N levels. Decreasing N supply had no influence on WUE in both inbred lines (Table 4). In winter oil-seed rape (Brück et al., 2001) and sweet potato plants (Kelm et al., 2001), a lower N level led to lower WUE, since N stress led to increased transpiration per unit leaf area and decreasing WUE (Kelm et al., 2001).

Flows and partitioning of N within plants

There was no significant difference in the amount of N taken up by both inbred lines at the HN level (Table 5), although Zi330 had a larger root system than Chen94-11 (Table 3). At the LN level, however, in which the the NO3− concentration supplied was only 1/50 of that at the HN level, the total amount of N taken up by Zi330 during the 10-d study period was 1·22 mmol, 31·8 % of that taken up under the HN treatment; the total amount of N taken up by Chen94-11 under the same conditions was 0·55 mmol, only 16·6% of that taken up under the HN treatment, showing higher N uptake by Zi330 at the LN level. The higher N uptake by Zi330 at the LN level could be related to its larger root system. Nitrogen uptake efficiency depends on root morphology and uptake ability (Reidenbach and Horst, 1997; Kamh et al., 2005). Cultivars with a deeper root system and higher root density take up more N from the soil (Wiesler and Horst, 1994; Oikeh et al., 1999). On the other hand, a demand-driven regulatory mechanism of N uptake has also been described (Engels et al., 1992; Imsande and Touraine, 1994). A sink-dependent stimulation of nitrate uptake in the bipartite system (Ricinus+Cuscuta) has been reported (Jeschke and Hilpert, 1997). Accordingly, the larger sink strength of Zi330 may have stimulated N uptake rate at the LN level.

Apart from the higher N uptake, the amount of N cycling within the plant at the LN level was also higher in Zi330 than in Chen94-11. In spite of more N uptake, the total N transported in the xylem in Zi330 at the HN level was less than that in Chen94-11. At the LN level, however, the total xylem-transported N in Zi330 was 2·7 times more than that in Chen94-11 (Table 5 and Fig. 2). Total N transported in the xylem and cycled in the phloem in both inbred lines grown at the LN level were significantly less than at the HN level (Table 4). It has been shown that K+ transported in the xylem of a tobacco plant grown under a high nutrient level (6 mm K and 15 mm NO3−) was almost the same as that grown under a low nutrient level (2·5 mm K and 2 mm NO3−), and the same was true for cycled K+ in the phloem ( Lu et al., 2005). Since K is not incorporated into the plant tissues but N is, the amounts of free nitrogenous compounds cycled in the phloem and transported in the xylem of plants grown at the LN level should be less than that of the plants grown under the HN treatment. In all cases, independent of inbred line and N level, the amount of N transported in the xylem was far more than that taken up in the same period, and the excess must have been compensated by export via the phloem. Even the amount of the cycled N in the phloem exceeded that currently taken up (Fig. 2). The amount of the phloem-cycled N contributed 65·4 % and 66·7 % of the xylem transported N in Zi330 and Chen94-11 grown at the HN level, and 71·7 % and 73·9 % at the LN level, respectively. In the N-deficient condition, the difference between maize hybrids for N use efficiency is mainly due to variation in N remobilization and utilization of accumulated N (Moll et al., 1982; Hirel et al., 2001).

The phloem-retranslocated N from shoot to roots came from leaves. Net N exported from the middle and lower leaves took place in both inbred lines grown at both N levels (Table 5 and Fig. 2). A model of total N flow in castor bean (Ricinus conmunis) showed that the exported N from leaves moved downwards to the root rather than directly feeding younger leaves higher up the shoot (Jeschke and Pate, 1991a). The same results were obtained in the present experiment. The importance of cycling of nutrients within plants for growth and development has been defined by Marschner et al. (1997). The upper parts of the shoot might benefit from cycling through the root of shoot-derived N (Jeschke and Pate, 1991b). In all cases in the present study, the amount of N directly imported via xylem into upper leaves exceeded that currently taken up by roots. Also the amount of N deposited in the upper leaves of both lines grown under the LN treatment was more than that taken up by roots at the same time (Fig. 2).

The ratio of reduced N to NO3− in the xylem sap of NO3−-fed plants can be used as a measure of proportional NO3− reduction between roots and shoot (Pate, 1973). In the present study, the major nitrogenous compound in the xylem sap was NO3−, when plants grew at the HN level, while the majority of nitrogenous compound was determined in the form of amino acid-N, when plants were grown at the LN level (Table 6). Low N supply shifted NO3−1 reduction towards the root (Andrews, 1986; Rufty et al., 1990). It is known that nitrate reductase is nitrate inducible. Many reports confirmed that the activity of nitrate reductase was positively correlated with nitrate supply and nitrate uptake (Godon et al., 1995, Fan et al., 2002). The presence of reduced N but not NO3−-N in the cycling flow from shoot to roots would overestimate the root assimilatory activity. It has been reported that over 60 % of the amino-N flux in the xylem was cycling in young wheat and rye plants (Cooper and Clarkson, 1989).

The results from the present study indicate that both NUE (defined as yield or biomass production on the bases of soil N or plant N, respectively) were consistent for the two maize lines. N-efficient maize inbred line Zi330 had higher N uptake and N cycling within the plant when grown under N-limited conditions. Also, Zi330 had a higher WUE at both N levels, which correlated with its lower shoot transpiration rate on a leaf dry weight basis. N-limited conditions shifted NO3− reduction towards the root in both lines. The results highlight the high degree of N reutilization by retranslocation via phloem, and provide further evidence that the cycling of N in plants can change, depending on N conditions.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Professor H. Lambers for valuable comments and careful correction of the manuscript, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No: 30390080) and Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University (IRT0511) for financial support.

LITERATURE CITED

- Andrews M. The partitioning of nitrate assimilation between root and shoot of higher plants. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1986;9:511–19. [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong M, Kirkby EA. Estimation of potassium recirculation in tomato plants by comparison of the rates of potassium and calcium accumulation in the tops with their fluxes in the xylem stream. Plant Physiology. 1979;63:1143–1148. doi: 10.1104/pp.63.6.1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brück H, Lugert I, Zhou W, Sattelmacher B. Why is physiological water-use efficiency lower under low nitrogen supply? In: Horst WJ, Schenk MK, Buerkert A, Claassen N, Flessa H, Frommer WB, et al., editors. Food security and sustainability of agro ecosystems through basic and applied research. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2001. pp. 400–401. [Google Scholar]

- Chen FJ. Screening for nitrogen-efficient maize genotypes and heterosis analysis. China: China Agricultural University; 2001. PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper HD, Clarkson DT. Cycling of amino-nitrogen and other nutrients between shoots and roots in cereals—a possible mechanism integrating shoot and root in the regulation of nutrient uptake. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1989;40:753–762. [Google Scholar]

- Duarte PJP, Larsson CM. Translocation of nutrients in N-limited, non-nodulated pea plants. Journal of Plant Physiology. 1993;141:182–187. [Google Scholar]

- Engels C, Münkle L, Marschner H. Effect of root zone temperature and shoot demand on uptake and xylem transport of macronutrient in maize (Zea mays L.) Journal of Experimental Botany. 1992;43:537–547. [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson T. Growth and shoot:root ratio of seedlings in relation to nutrient availability. Plant and Soil. 1995;168–169:205–214. [Google Scholar]

- Fan XH, Tang C, Rengel Z. Nitrate uptake, nitrate reductase distribution and their relation to proton release in five nodulated grain legumes. Annals of Botany. 2002;90:315–323. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcf190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godon C, Caboche M, Daniel-Vedele F. Use of the biolistic process for the analysis of nitrate-inducible promoters in transient expression assay. Plant Science. 1995;111:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- Guo FQ, Young J, Crawford NM. The nitrate transporter AtNRT1middot;1(CHL1) functions in stomatal opening and contributes to drought susceptibility in arabidopsis. The Plant Cell. 2003;15:107–117. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirel B, Bertin P, Quilleré I, Bourdoncle W, Attagnant C, Dellay C, et al. Towards a better understanding of the genetic and physiological basis for nitrogen use efficiency in maize. Plant Physiology. 2001;125:1258–1270. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.3.1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imsande J, Touraine B. N demand and the regulation of nitrate uptake. Plant Physiology. 1994;105:3–7. doi: 10.1104/pp.105.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke WD, Hilpert A. Sink-stimulated photosynthesis and sink-dependent increase in nitrate uptake: nitrogen and carbon relations of the parasitic association Cuscuta reflexa–Ricinus communis. Plant, Cell and Environment. 1997;20:47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke WD, Pate JS. Modeling of the uptake, flow and utilization of C, N and H2O within whole plants of Ricinus conmunis L. based on empirical data. Journal of Plant Physiology. 1991a;137:488–498. [Google Scholar]

- Jeschke WD, Pate JS. Modelling of the partitioning, assimilation and storage of nitrate within root and shoot organs of castor bean (Ricinus communis L.) Journal of Experimental Botany. 1991b;42:1091–1103. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Li CJ, Jeschke WD, Zhang FS. Effect of top excision and replacement by 1-naphthylacetic acid on partition and flow of potassium in tobacco plants. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2001;52:2143–2150. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.364.2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamh M, Wiesler F, Ulas A, Horst WJ. Root growth and N-uptake activity of oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.) cultivars differing in nitrogen efficiency. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science. 2005;168:130–137. [Google Scholar]

- Kelm M, Brük H, Hermann M, Sattelmacher B. The effect of low nitrogen supply on yield and water-use efficiency of sweet potato (Ipomoea batatas L.) In: Horst WJ, Schenk MK, Buerkert A, Claassen N, Flessa H, Frommer WB, et al., editors. Food security and sustainability of agro ecosystems through basic and applied research. Dordrecht: Kluwer; 2001. pp. 402–403. [Google Scholar]

- Lambers H, Simpson RJ, Beilharz VC, Dalling MJ. Growth and translocation of C and N in wheat (Triticum aestivum) grown with a split root system. Physiologia Plantarum. 1982;56:421–429. [Google Scholar]

- Lu YX, Li CJ, Zhang FS. Transpiration, potassium uptake and flow in tobacco as affected by nitrogen forms and nutrient levels. Annals of Botany. 2005;95:991–998. doi: 10.1093/aob/mci104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. 2nd edn. London: Academic Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H, Kirkby EA, Engels C. Importance of cycling and recycling of mineral nutrients within plants for growth and development. Botanica Acta. 1997;110:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Moll RH, Kamprath EJ, Jackson WA. Analysis and interpretation of factors which contribute to efficiency of N utilization. Agronomy Journal. 1982;74:562–564. [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DW, Somers LE. Determination of total nitrogen in plant material. Agronomy Journal. 1973;65:109–112. [Google Scholar]

- Oikeh SO, Kling JG, Horst WJ, Chude VO, Carsky RJ. Growth and distribution of maize roots under nitrogen fertilization in plinthite soil. Field Crops Research. 1999;62:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Pate JS. Uptake, assimilation and transport of nitrogen compounds by plants. Soil Biology and Biochemistry. 1973;5:109–119. [Google Scholar]

- Peuke AD, Jeschke WD. The uptake and flow of C, N and ions between roots and shoots in Richinus communis L. I. Grown with ammonium or nitrate as nitrogen source. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1993;44:1167–1176. [Google Scholar]

- Peuke AD, Hartung W, Jeschke WD. The uptake and flow of C, N and ions between roots and shoots in Ricinus communis L. II. Growth with low or high nitrate supply. Journal of Experimental Botany. 1994;45:733–740. [Google Scholar]

- Reidenbach G, Horst WJ. Nitrate-uptake capacity of different root zones of Zea mays (L.) in vitro and in situ. Plant and Soil. 1997;196:295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Rufty TW, Jr, MacKown CT, Volk RJ. Alterations in nitrogen assimilation and partitioning in nitrogen-stressed plants. Physiologia Plantarum. 1990;79:85–95. [Google Scholar]

- SAS. SAS/STAT guide for personal computers. 6th edn. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Seel WE, Jeschke WD. Simultaneous collection of xylem sap from Rhinanthus minor and the hosts Hordeum and Trifolium: hydraulic properties, xylem sap composition and effects of attachment. New Phytologist. 1999;143:281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson RJ, Lambers H, Dalling MJ. Nitrogen redistribution during grain growth in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). IV. Development of a quantitative model of the translocation of nitrogen to the grain. Plant Physiology. 1983;71:7–14. doi: 10.1104/pp.71.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesler F, Horst WJ. Root growth and nitrate utilization of maize cultivars under field conditions. Plant and Soil. 1994;163:267–277. [Google Scholar]