Abstract

Background

The safety of bilateral total knee arthroplasties (BTKA) during the same hospitalization remains controversial. We sought to study differences in perioperative outcomes between unilateral and BTKA, and further compare BTKAs performed during the same versus different operations during the same hospitalization.

Methods

Nationwide Inpatient Sample data from 1998 to 2006 were analyzed. Entries for unilateral and BTKA procedures performed on the same day (simultaneous) and separate days (staged) during the same hospitalization were identified. Patient and health-care system related demographics were determined. The incidence of in-hospital mortality and procedure related complications was estimated and compared between groups. Multivariate regression was used to identify independent risk factors for morbidity and mortality.

Results

Despite younger average age and lower comorbidity burden, procedure related complications and in-hospital mortality were more frequent after BTKA than after unilateral procedures (9.45% vs. 7.07% and 0.30% vs. 0.14%, P<0.0001 each). An increased rate of complications was associated with a staged versus simultaneous approach with no difference in mortality (10.30% vs. 9.15% (P<0.0001) and 0.29% vs. 0.26% (P=0.2875)). Independent predictors for in-hospital mortality included: BTKA (simultaneous: OR 2.23, CI=[1.69; 2.95], P<0.0001; staged: OR 2.01, CI=[1.28; 3.41], P=0.0031), male gender (OR 2.02, CI=[1.75, 2.34], P<0.0001), age above 75 years (OR 3.96 CI=[2.77, 5.66], P<0.0001), and the presence of a number of comorbidities and complications.

Conclusion

BTKAs carry increased risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality compared to unilateral procedures. Staging BTKA procedures during the same hospitalization offers no mortality benefit, and may even expose patients to increased morbidity.

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) remains the most effective treatment of end stage osteoarthritis. When both joints are affected, bilateral TKA (BTKA) reduces the overall cost of care by 18 to 36% and length of hospital stay by approximately 4 to 6 days. Furthermore, this approach may reduce overall use of pain medication and recovery time (1–3). Despite these advantages, the safety of BTKA remains controversial (4–7). Recent publications that utilize large patient samples have concluded that BTKA surgery is associated with an increase in morbidity and mortality when compared to staged and unilateral procedures. These studies include a meta-analysis of randomized trials (6), a review from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register (4), and an analysis of data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey (7).

On the other side, a number of researchers and clinicians maintain that the bilateral approach carries little to no additional risk in carefully selected patients (8, 9). The studies supportive of BTKA, however, tend to represent outcomes from restricted, small patient samples from specialized, high volume institutions and surgeons, who may have less complications, but whose experience may not allow for generalizability. The small sample sizes in these studies also prohibit adequate representation of low incidence outcomes (10). In view of these conflicting results, nationally representative trend data suggest that clinicians have adopted a more conservative approach when selecting patients as candidates for BTKA, as evidenced by a decrease in the prevalence of cardiopulmonary disease and advanced age among BTKA recipients (11). In the absence of official guidelines, some hospitals have adopted advisories against the performance of BTKA procedures in patients that are deemed to be at increased risk for adverse outcomes. These include patients above the age of 75 years, those with an American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status classification of three or greater, and those with significant cardiopulmonary comorbidities (9). However, these criteria are often put into question as the information on risk factors for adverse outcomes are derived from studies that are burdened by limitations of small sample size and inclusion of restricted patient population, (e.g. single institution, academic centers or Medicare recipients) (12–15).

In a further attempt to reduce unfavorable outcomes associated with this elective procedure, and in addition to selecting suitable candidates, some physicians perform procedures on different days during the same hospitalization as to strike a balance between the benefits of BTKA and the related clinical risk (9, 16). However, this strategy is largely based on very limited information. Only two single institution studies (16, 17) have attempted to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of staging procedures during the same hospitalization with an interval of 2–7 days apart. While no effect in one (17) and a negative effect associated with staging was found in the other (16), both studies were burdened by the inclusion of a small number of subjects, thus restricting their ability to adequately capture low incidence outcomes. In general, population based data on this topic remain rare as most studies addressing this problem are limited by factors mentioned previously. Furthermore, they insufficiently address outcomes in the immediate perioperative setting (12–15).

To overcome some of these limitations, we used data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), the largest annual all payer database in the United States and sought to study 1) if differences in perioperative outcomes between unilateral TKA (UTKA) and BTKA exist, 2) if procedures performed on the same day (simultaneously) versus at different operations (staged) during the same hospitalization were associated with different outcomes and 3) if risk factors for peri-operative morbidity and mortality after TKA procedures could be identified.

Materials and Methods

NIS annual data files are sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and are commercially obtained from the Hospital Cost and Utilization Project. Detailed information on the NIS design can be found on the internet € £. The NIS represents the largest all payer inpatient discharge database in the United States and contains information from approximately 8 million hospital admissions per year. Having grown since its inception in 1988 when it included data from 8 states, the most recent data files represent a 20% stratified sample (i.e. designed to representatively include hospitals of different size, location, teaching status, geographic area, and ownership) of approximately 1000 hospitals in 38 states. It includes over 100 clinical and non clinical data elements, such as diagnoses, procedures, admission and discharge status, patient demographics (e.g., gender, age, race, payment source, and length of stay) and hospital characteristics (e.g., size, location, and teaching status). The NIS provides weights that allow for nationally representative estimates. A large number of studies addressing various questions across the spectrum of medical specialties ¥, including anesthesiology (18–20) has used the NIS database. The use of this study was exempt from review by the institutional review board as the data used in this study are sufficiently de-identified.

Study Sample and Statistical Analysis

Our study sample consists of all data in NIS for each year between 1998 and 2006. In order to improve the sample representativeness of NIS, the sampling and weighting strategy was modified beginning with the 1998 data. To avoid any bias introduced by this change we chose to include data collected only after 1998 in our study. At the time of analysis, the 2006 dataset was the latest available. Discharges with an International Classification of Diseases- 9th revision-Clinical Modification procedure code for primary TKA (81.54) were identified and included in the sample. Two procedure type groups were created: UTKA and BTKA. UTKAs were identified by the occurrence of the procedure code 81.54 once, those with BTKA had this procedure code listed twice, as reported previously (7, 11, 12). The prevalence of procedure sub-types and respective demographics (age, gender, race, disposition status, primary source of payment, distribution of procedures by hospital size, teaching status, location, and length of care) were estimated. For a large number of cases (approximately 40%) the race category was not available. We imputed the missing discharges as “white”. This was the largest group in our study and this approach has been previously described by Bateman et al. (18). Frequencies of procedure-related complications were analyzed by determining cases that listed Classification of Diseases- 9th revision-Clinical Modification diagnosis codes specifying complications of surgical and medical care (International Classification of Diseases- 9th revision-Clinical Modification diagnosis codes 996.X to 999.X) (appendix 1). In addition, we studied the prevalence of selected adverse diagnoses, including pulmonary embolism, venous thrombosis, respiratory insufficiency after trauma or surgery/Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome, and acute posthemorrhagic anemia, using the International Classification of Diseases- 9th revision-Clinical Modification diagnosis code system (appendix 1). Comorbidity profiles were analyzed by determining the prevalence of a number of disease states as defined in the Comorbidity Software provided by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality #. In order to determine the overall comorbidity burden, comorbidity indices were calculated as described by Charlson et al. (21) and were adjusted for use with administrative data as recommended by Deyo et al. (22). Differences in in-hospital mortality between procedure sub-types were assessed. We further compared in hospital mortality and complications among BTKA recipients whose procedures were performed on the same (simultaneously) versus a different day (staged) of their hospitalization. Unweighted frequencies representing the actual number of entries in the NIS as well as weighted frequencies calculated to provide national estimates are presented in this study.

Appendix 1.

List of International Classification of Diseases- 9th revision-Clinical Modification diagnosis codes included to identify comorbidities, adverse diagnosis, and complications among discharges. (Four- and five-digit codes are included under the respective three-and four-digit codes.)

| Procedure Related Complications | |

| Device Related | 996 |

| Central Nervous System | 9970 |

| Cardiac | 9971 |

| Peripheral Vascular | 9972 |

| Respiratory | 9973 |

| Gastrointestinal | 9974 |

| Genitourinary | 9975 |

| Other Organ Specific | 9976 – 9979 |

| Postoperative Shock | 9980 |

| Hematoma/Seroma | 9981 |

| Accidental Puncture/Laceration | 9982 |

| Disruption Operative Wound | 9983 |

| Postoperative Infection | 9985 |

| Other Complications of Procedure | 9986 – 9989 |

| Complications of Medical Care | 999 |

| Other Adverse Events | |

| Acute Posthemorrhagic Anemia | 2851 |

| Pulmonary Embolism | 4151 |

| Pulmonary Insufficiency after | |

| Trauma and Surgery/ | |

| Adults respiratory Distress Syndrome | 5185 |

| Venous Thrombotic Events | 4511, 4512, 4518, 4519, 4532, 4538, 4539 |

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). To facilitate analysis of data collected in a complex survey design (including stratification, clustering, replication, and unequal probabilities of selection) and to obtain consistent estimates of mean and variance parameters taking into account the complex survey data setting, we utilized SAS procedures SURVERYMEANS, SURVEYFREQ, and SURVEYLOGISTIC for descriptive, comparative, (see table 1–table 3) and logistic regression analysis (table 4–table 7). Continuous variables are presented as mean and 95% confidence interval (CI) and categorical variables are described as percentages. Although the conventional threshold of statistical significance (i.e., p-value<0.05) was used to guide model development, we also reported full p-values and 95% CIs to let the readers interpret the significance of the findings in light of the potential undue effect very large sample size might have on the p-values.

Table 1. Demographics of Uni- and Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty Discharges.

Tabulated are patient and healthcare system related demographics for discharges after uni- and bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Presented are unweighted and weighted frequencies as well as proportions in percent for either procedure type.

| Demographics of Uni- and Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty Discharges | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Knee Arthroplasty Type | Unilateral | Bilateral | |||||

| N =unweighted (weighted) | 626,439 (3,055,368) | 43,350 (212,9940) | |||||

| N (unweighted/weighted/percent) | F | WF | % | F | WF | % | p-value |

| Age groups (years) | <0.0001 | ||||||

| 0–44 | 13030 | 63458 | 2.08 | 673 | 3273 | 1.54 | |

| 45–64 | 215570 | 1050251 | 34.37 | 17452 | 85590 | 40.18 | |

| 65–75 | 222142 | 1082807 | 35.44 | 16123 | 79178 | 37.17 | |

| >=75 | 175697 | 858851 | 28.11 | 9102 | 44953 | 21.11 | |

| Gender | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Male | 222537 | 1084672 | 35.56 | 17947 | 88008 | 41.35 | |

| Female | 402856 | 1965684 | 64.44 | 25367 | 124813 | 58.65 | |

| Race | <0.0001 | ||||||

| White | 559020 | 2730731 | 89.31 | 39663 | 195102 | 91.54 | |

| Black | 31037 | 150296 | 4.92 | 1617 | 7856 | 3.69 | |

| Hispanic | 23371 | 111047 | 3.63 | 993 | 4759 | 2.23 | |

| Other | 13489 | 65589 | 2.15 | 1105 | 5407 | 2.54 | |

| Insurance | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Medicare | 38188 | 1863334 | 61.06 | 23670 | 116331 | 54.71 | |

| Medicaid | 16116 | 78918 | 2.59 | 708 | 3500 | 1.65 | |

| Private/ HMO | 204848 | 998328 | 32.71 | 17719 | 87024 | 40.93 | |

| Other | 22855 | 111056 | 3.64 | 1185 | 5781 | 2.72 | |

| Discharge Status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Routine | 168005 | 822165 | 27.04 | 6304 | 31038 | 14.66 | |

| Short Term Hospital | 4891 | 24136 | 0.79 | 495 | 2442 | 1.15 | |

| Other Transfers | 276517 | 1352432 | 44.48 | 30699 | 151025 | 71.33 | |

| Home Health Care | 172743 | 836380 | 27.51 | 5432 | 26481 | 12.51 | |

| Against Medical Advice | 175 | 864 | 0.03 | 15 | 75 | 0.04 | |

| Died in Hospital | 845 | 4121 | 0.14 | 131 | 636 | 0.3 | |

| Alive, Destination Unknown | 112 | 528 | 0.02 | 3 | 16 | 0.01 | |

| Hospital Size | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Small | 91796 | 429435 | 14.05 | 6006 | 28268 | 13.26 | |

| Medium | 162036 | 779629 | 25.51 | 10612 | 51272 | 24.06 | |

| Large | 372752 | 1847002 | 60.44 | 26761 | 133589 | 62.68 | |

| Hospital Location | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Rural | 87411 | 443945 | 14.53 | 5349 | 27425 | 12.87 | |

| Urban | 539173 | 2612121 | 85.47 | 38030 | 185704 | 87.13 | |

| Teaching Status | <0.0001 | ||||||

| Non-teaching | 374122 | 1804006 | 59.03 | 21294 | 106439 | 49.94 | |

| Teaching | 252462 | 1252060 | 40.97 | 22085 | 106690 | 50.06 | |

F=Frequency; HMO=Healthcare Maintenance Organization; WF=Weighted Frequency; %=percentage

Table 3. Procedure Related Complications Among Simultaneous and Staged Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty Discharges.

The incidence of complications coded as procedure related for simultaneous and staged bilateral total knee arthroplasties are shown.

| Procedure Related Complications Among Simultaneous and Staged Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty Discharges | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simultaneous | Staged | ||||||

| N (unweighted/weighted/percent) | F | WF | % | F | WF | % | P-value |

| Device Related Complications | |||||||

| Device Related | 130 | 633 | 0.51 | 41 | 204 | 0.49 | 0.6249 |

| Organ Specific Complications | |||||||

| CNS | 53 | 261 | 0.21 | 23 | 118 | 0.28 | 0.0092 |

| Cardiac | 427 | 2105 | 1.69 | 133 | 671 | 1.61 | 0.2364 |

| Peripheral Vascular | 115 | 591 | 0.47 | 27 | 138 | 0.33 | 0.0002 |

| Respiratory | 282 | 1371 | 1.1 | 116 | 584 | 1.4 | <0.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 344 | 1681 | 1.35 | 149 | 760 | 1.82 | <0.0001 |

| Genitourinary | 270 | 1329 | 1.07 | 106 | 544 | 1.3 | 0.0001 |

| Other Complications of Procedure | |||||||

| Shock | 16 | 76 | 0.06 | 3 | 18 | 0.04 | 0.1916 |

| Hematoma/Seroma | 354 | 1709 | 1.37 | 119 | 585 | 1.4 | 0.6913 |

| Puncture Vessel/Nerve | 21 | 103 | 0.08 | 7 | 34 | 0.08 | 0.927 |

| Wound Dehiscence | 15 | 70 | 0.06 | 3 | 15 | 0.04 | 0.1194 |

| Infection | 37 | 183 | 0.15 | 17 | 85 | 0.2 | 0.013 |

| Other | 486 | 2412 | 1.94 | 219 | 1084 | 2.59 | <0.0001 |

| Medical Complication | 59 | 297 | 0.24 | 25 | 124 | 0.3 | 0.0391 |

CNS=Central Nervous System; F=Frequency; WF=Weighted Frequency; %=percentage

Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression models-model selection and validation.

Presented is information regarding the four logistic regression models used to determine risk factors for morbidity and mortality associated with total knee arthroplasty. Results of the validation studies are also reported.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcomes | Mortality outcome (dead/alive) |

Mortality outcome (dead/alive) |

Mortality outcome (dead/alive) |

Any procedure related complication(yes/no) |

| Predictors | Comorbidity index | Individual comorbidities |

Perioperative procedure related complications |

Individual comorbidities |

| Covariates | Procedure types, patient demographic and health care system related variables |

Procedure types, patient demographic and health care system related variables |

Procedure types, Comorbidity index, patient demographic and health care system related variables |

Procedure types, patient demographic and health care system related variables |

|

C-statistic on the training dataset (80%) |

0.72 | 0.77 | 0.80 | 0.77 |

|

C-statistic on the validation dataset (20%) |

0.71 | 0.79 | 0.79 | 0.75 |

|

Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p-value) on the training dataset (80%) |

0.57 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

|

Hosmer-Lemeshow test (p-value) on the validation dataset (20%) |

0.85 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.14 |

Table 7. Risk Factors for Any Procedure Related Complications after Total Knee Arthroplasty-Comorbidities (Model 4).

Listed are the results of the logistic regression model 4 detailing the odds ratio and 95%-confidence intervals associated with various comorbidities for the outcome of the occurrence of any procedure related complication. Risk factors with a P-value <0.05 are presented in bold letters.

| Risk Factors for Any Procedure Related Complications after Total Knee Arthroplasty-Comorbidities (Model 4) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | Regression Coefficient Estimate |

Odds Ratio | Lower -95%CI | Upper -95%CI | P-Value |

| Alcohol Abuse | 0.33 | 1.4 | 1.22 | 1.6 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 0.11 | 1.12 | 1.08 | 1.16 | <0.0001 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 0.7 | 2.01 | 1.91 | 2.11 | <0.0001 |

| Uncomplicated Diabetes Mellitus | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.1367 |

| Complicated Diabetes Mellitus | 0.29 | 1.34 | 1.22 | 1.47 | <0.0001 |

| Liver Dysfunction | 0.08 | 1.09 | 0.93 | 1.26 | 0.287 |

| Coagulopathy | 0.63 | 1.88 | 1.74 | 2.04 | <0.0001 |

| Neurologic Disorders | 0.15 | 1.16 | 1.08 | 1.25 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 0.02 | 1.02 | 0.98 | 1.06 | 0.382 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 0.22 | 1.24 | 1.15 | 1.34 | <0.0001 |

| Renal Disease | 0.31 | 1.36 | 1.23 | 1.5 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary Circulatory Disease | 1.06 | 2.88 | 2.64 | 3.14 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac Valvular Disorders | 0.19 | 1.21 | 1.15 | 1.28 | <0.0001 |

| Electrolyte/Fluid Abnormalities | 0.89 | 2.43 | 2.35 | 2.52 | <0.0001 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 0.35 | 1.42 | 1.01 | 1.98 | 0.0423 |

| Cancer | 0.04 | 1.04 | 0.89 | 1.21 | 0.6356 |

The data-splitting approach (23) was employed for model development and validation by dividing the entire dataset into a training dataset (80%) on which the model was developed and the rest of 20% of data which was utilized for validation. Univariate analysis for differences between procedure types was conducted by t-test for continuous, and chi-square test for categorical variables. Four multivariate logistic regression models were constructed and odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were estimated to determine independent predictors for in-hospital morbidity and mortality (Table 4). Models 1–3 were fitted to identify 1) the effect of demographic variables and overall comorbidity burden, 2) the effect of individual comorbidities, and 3) the effect of perioperative complications on in-hospital mortality (outcome variable), respectively. Model 4 was constructed to determine the impact of individual comorbidities on the occurrence of any procedure related complications as defined above and detailed in the appendix 1. Procedure sub-types (UTKA, simultaneous BTKA, and staged BTKA), patient demographic variables (age, gender, and race) and health care system related variables (primary source of payment, discharge status, hospital bed size, location, and teaching status) were retained in all four models as covariates to reduce potential background bias. In Model 1, overall comorbidity was summarized by the Deyo comorbidity index (22). Individual comorbidities including alcohol abuse, chronic lung disease, etc. (see full list in Table 5) were substituted for the Deyo comorbidity index in Model 2. In Model 3 complications including those affecting the central nervous system, cardiac etc. (see full list in Table 6) were considered as predictors while controlling for overall comorbidity burden using the Deyo comorbidity index (22). A dichotomous outcome variable showing whether a procedure related complication occurred during the hospitalization was created for Model 4 and individual comorbidities (see full list in Table 7) were included as predictors. For each individual predictor, odds ratio, 95% CIs and p-value were computed.

Table 5. Risk Factors for Perioperative Mortality after Total Knee Arthroplasty -Comorbidities (Model 2).

Listed are the results of the logistic regression model 2 detailing the odds ratio and 95%-confidence intervals associated with various comorbidities for the outcome of mortality. Risk factors with a P-value <0.05 are presented in bold letters.

| Risk Factors for Perioperative Mortality after Total Knee Arthroplasty -Comorbidities (Model 2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbidity | Regression Coefficient Estimate |

Odds Ratio | Lower -95%CI | Upper -95%CI | P-Value |

| Alcohol Abuse | 0.25 | 1.28 | 0.57 | 2.88 | 0.552 |

| Chronic Lung Disease | 0.18 | 1.2 | 0.98 | 1.47 | 0.0844 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 1.62 | 5.03 | 4.14 | 6.11 | <0.0001 |

| Uncomplicated Diabetes Mellitus | 0.12 | 1.13 | 0.92 | 1.39 | 0.2475 |

| Complicated Diabetes Mellitus | 0.13 | 1.13 | 0.67 | 1.92 | 0.643 |

| Liver Dysfunction | 0.28 | 1.32 | 0.55 | 3.17 | 0.5381 |

| Coagulopathy | 0.96 | 2.62 | 1.88 | 3.67 | <0.0001 |

| Neurologic Disorders | 1.03 | 2.8 | 1.06 | 3.81 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | −0.26 | 0.77 | 0.57 | 1.03 | 0.08 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 0.4 | 1.5 | 1.01 | 2.22 | 0.0422 |

| Renal Disease | 1.25 | 3.49 | 2.52 | 4.84 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary Circulatory Disease | 2.46 | 11.75 | 9.05 | 15.25 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac Valvular Disorders | 0.12 | 1.12 | 0.84 | 1.49 | 0.4278 |

| Electrolyte/Fluid Abnormalities | 1.3 | 3.67 | 3.06 | 4.4 | <0.0001 |

| Metastatic Cancer | 1.33 | 3.76 | 1.09 | 13.02 | 0.0364 |

| Cancer | 0.18 | 1.2 | 0.54 | 2.68 | 0.6535 |

Table 6. Risk Factors for Peripoerative Mortality after Total Knee Arthroplasty-Procedure Related Complications (Model 3).

Listed are the results of the logistic regression model 3 detailing the odds ratio and 95%-confidence intervals associated with various procedure related complications for the outcome of mortality. Risk factors with a P-value <0.05 are presented in bold letters.

| Risk Factors for Peripoerative Mortality after Total Knee Arthroplasty-Procedure Related Complications (Model 3) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complications | Regression Coefficient Estimate |

Odds Ratio | Lower-95%CI | Upper -95%CI | P-Value |

| Device Related Complications | |||||

| Device Related | 0.76 | 2.13 | 1.19 | 3.8 | 0.0104 |

| Organ Specific Complications | |||||

| CNS | 3.13 | 22.77 | 14.28 | 36.31 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac | 2.65 | 14.19 | 11.25 | 17.91 | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral Vascular | 1.69 | 5.42 | 0.81 | 36.06 | 0.0807 |

| Respiratory | 0.76 | 2.13 | 1.39 | 3.26 | 0.0005 |

| Gastrointestinal | 1.36 | 3.9 | 2.64 | 5.77 | <0.0001 |

| Genitourinary | 0.4 | 1.5 | 0.89 | 2.52 | 0.1291 |

| Other Complications of Procedure | |||||

| Shock | 2.71 | 15.1 | 3.88 | 58.81 | <0.0001 |

| Hematoma/Seroma | 0.29 | 1.33 | 0.75 | 2.37 | 0.3338 |

| Puncture Vessel/Nerve | −1.02 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 64.53 | 0.7006 |

| Wound Dehiscence | 1.88 | 6.56 | 2.13 | 20.2 | 0.001 |

| Infection | 0.51 | 1.67 | 0.6 | 4.65 | 0.3245 |

| Other | 0.27 | 1.31 | 0.71 | 2.42 | 0.3905 |

| Medical Complication | −1.4 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 4.74 | 0.3527 |

CNS=Central Nervous System

Multicollinearity was judged by checking the value inflation factor and the condition index. The conventional criterion of considering multicollinearity to be absent if the value inflation factor is <10 and condition index <30 was utilized. Full multivariate logistic regression models were reduced by excluding any predictors with p-values greater than 0.05. Akaike’s information criterion was implemented to compare full models with reduced models for model selection. Lower Akaike’s information criterion scores were considered indicative of a better fit. The four final models were validated on both the training and the validation dataset by a test of model discrimination using the c statistic and a test of model calibration using the Hosmer –Lemeshow (H–L) test (24). The c-statistic is the same as the area under the receiver-operating characteristic curve (25), and is used to measure how well the model discriminates between observed data at different levels of the outcome. A c-statistic value between 0.7 and 0.8 is considered indicative of acceptable discrimination (26). The H–L test evaluates whether a logistic regression model is well calibrated so that the probability predictions from the model reflect the true occurrence of events in the data. Nonsignificant p-values for this test are considered indicative of a well calibrated model. However, it is important to keep in mind that caution needs to be taken for interpreting significant p-value for the H–L in the setting of large sample sized study (27).

To further test the validity of the NIS as a data source for our study context, we compared the rate of our primary outcome of in-hospital mortality to that previously reported in the literature over a similar time frame in the clinical setting, as described by Bateman et al. (18). Similar reported mortality rates in the literature would therefore underline confidence in the robustness of our data source.

Results

Demographics of UTKA and BTKA discharges

We identified a total of 670,305 admissions between 1998 and 2006 during which a TKA procedure was performed. This represented a weighted national estimate of 3,270,836 hospitalizations. Of those 6.52% had bilaterally performed procedures. The average age was 67.46 (CI=[67.43, 67.49]) years for admissions undergoing UTKA and 66.14 (CI=[66.05, 66.23]) years for BTKA procedures (P<0.0001).

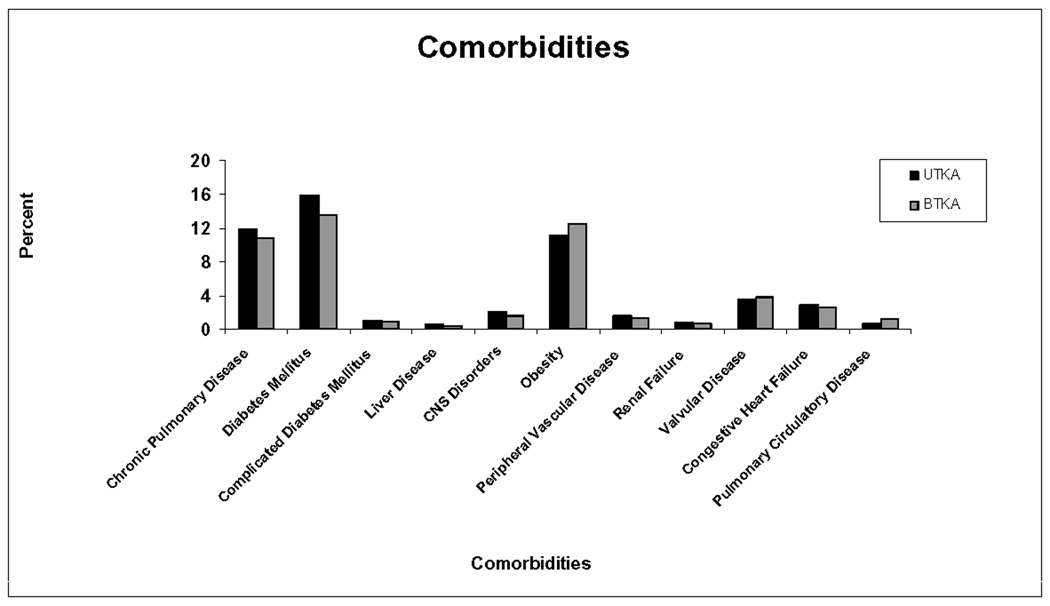

Table 1 contains information on patient and health care system related demographic variables. Length of hospital stay was significantly longer for BTKA compared to UTKA recipients (4.71 days (CI=[4.68, 4.74]) vs. 3.99 (CI=[3.98, 4.00]) (P<0.0001). Comorbidities under study tended to be more prevalent among UTKA than BTKA recipients, except for obesity, cardiac valvular and pulmonary circulatory disease (Figure1). The average comorbidity index among admissions for BTKA recipients was significantly lower compared to those for UTKA (0.48(CI=[0.47, 0.49]) versus 0.55(CI=[0.54, 0.56]) (P<0.0001)).

Figure 1.

Depicted is the prevalence of selected comorbidities among uni- and bilateral total knee arthroplasty discharges. BTKA=Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty; CNS= Central Nervous System; UTKA=Unilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty

Outcomes after UTKA and BTKAs

Complications considered procedure related were more frequent among BTKA versus UTKA recipients (9.45% vs. 7.07% (P<0.0001)) (Table 2). The incidence of pulmonary embolism (0.82% vs. 0.39%), venous thrombosis (1.21% vs. 0.72%), and Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome (0.48% vs. 0.25%) was also increased among BTKA patients compared to UTKA recipients (P<0.0001). Acute posthemorrhagic anemia was coded at about double the rate among BTKA versus UTKA procedures (27.02% vs. 14.52% (P<0.0001)). In-hospital mortality was higher among BTKA compared to UTKA recipients (0.30% vs. 0.14% (P<0.0001). The average age of fatalities after UTKA and BTKA was similar (74.37 (CI=[73.74, 75.01]) vs. 73.07 (CI=[71.54, 74.60]) years, (P=0.1144). Mortalities after BTKA occurred sooner after admission to the hospital than after UTKA procedures (6.86 (CI=[5.20, 8.53]) days versus 8.41 (CI=[7.55, 9.27]) days, but this difference was not significant (P=0.1184).

Table 2. Procedure Related Complications Among Uni- and Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty Discharges.

The incidence of complications coded as procedure related for uni- and bilateral total knee arthroplasties are shown.

| Procedure Related Complications Among Uni- and Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasty Discharges | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Knee Arthroplasty Type | Unilateral | Bilateral | |||||

| N (unweighted/weighted/percent) | F | WF | % | F | WF | % | P-value |

| Device Related Complications | |||||||

| Device Related | 5420 | 26411 | 0.86 | 228 | 1115 | 0.52 | <0.0001 |

| Organ Specific Complications | |||||||

| CNS | 763 | 3764 | 0.12 | 107 | 531 | 0.25 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac | 5849 | 28700 | 0.94 | 720 | 3562 | 1.67 | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral Vascular | 1501 | 7374 | 0.24 | 159 | 809 | 0.38 | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory | 5680 | 27827 | 0.91 | 550 | 2700 | 1.27 | <0.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 4603 | 22510 | 0.74 | 631 | 3098 | 1.45 | <0.0001 |

| Genitourinary | 4839 | 23747 | 0.78 | 497 | 2453 | 1.15 | <0.0001 |

| Other Complications of Procedure | |||||||

| Shock | 97 | 467 | 0.02 | 33 | 161 | 0.08 | <0.0001 |

| Hematoma/Seroma | 5934 | 28731 | 0.94 | 601 | 2915 | 1.37 | <0.0001 |

| Puncture Vessel/Nerve | 426 | 2090 | 0.07 | 39 | 192 | 0.09 | 0.0003 |

| Wound Dehiscence | 297 | 1443 | 0.05 | 28 | 134 | 0.06 | 0.0013 |

| Infection | 1393 | 6800 | 0.22 | 66 | 327 | 0.15 | <0.0001 |

| Other | 10468 | 50955 | 1.67 | 891 | 4387 | 2.06 | <0.0001 |

| Medical Complication | 789 | 3876 | 0.13 | 106 | 257 | 0.25 | <0.0001 |

CNS=Central Nervous System; F=Frequency; WF=Weighted Frequency; %=percentage

Staged versus simultaneous BTKAs during the same hospitalization

22.33% (9688) of all entries for BTKA did not allow for determination of timing of one or both procedures and were therefore excluded from the sub-group analysis. To make sure that the observed data could sufficiently represent the target patient population, we conducted a sensitivity analysis and found that our results are reliable and robust in so far as 1) the observed BTKA and the missing BTKA followed similar distributions in patient demographics, and 2) in the extreme case when all missing BTKAs were considered as simultaneous BTKAs or staged BTKAs, the risk factors for mortality and any procedure related complications found by logistic regression retained their significance.

Of the BTKA discharges included, 74.8% were performed simultaneously, while the remainder was performed on separate days of the hospital admission. The average time between staged procedures was 3.59 (CI=[3.39, 3.79]) days. The average age of discharges associated with staged procedures was 66.18 (CI=[65.96, 66.39]) years and 66.00 (CI=[65.88, 66.12]) with simultaneous BTKA (P=0.1567). There was no difference in the overall comorbidity severity between the simultaneous versus staged group (comorbidity index 0.48 (CI=[0.47, 0.49]) for simultaneous and 0.49 (CI=[0.48, 0.51]) for staged BTKA, respectively (P=0.3332)). Length of stay was longer after staged BTKA compared to simultaneous procedures (5.37 (CI=[5.30, 5.43]) days vs. 4.52 (CI=[4.48, 4.56]) days, respectively (P<0.0001)).

Generally, procedure related complications were more frequently encountered in discharges associated with staged compared to simultaneous BTKA (10.30% vs. 9.15%, respectively (P<0.0001)). Table 3 details the incidence of specific procedure related complications. For all categories, staged procedures had either a higher or similar incidence of complications.

Adverse events such as Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome, and posthemorrhagic anemia occurred at higher rates after staged procedures compared to simultaneous BTKA (0.62% vs. 0.40% (P<0.0001) and 29.61% vs. 25.17% (P<0.0001), respectively). Venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism occurred more frequently among simultaneous procedure recipients (1.48% vs. 1.22% (P=0.0002) and 0.89% vs. 0.77% (P=0.0218), respectively).

No statistical difference in the rates of in-hospital mortality was seen between either BTKA approach (0.29% for simultaneous and 0.26% for staged BTKA, respectively (P=0.2875)).

Risk Factors for Perioperative Morbidity and Mortality after TKA

An over proportional number of deaths occurred among BTKA recipients (13.42% of total mortalities) compared to the prevalence (6.51%) of BTKA among the study sample. Multivariate regression revealed a number of independent risk factors for mortality after TKA. Patient related factors that significantly increased the risk for perioperative mortality were male gender (OR 2.02 CI=[1.75, 2.34], P<0.0001), and age (age above 75: OR 3.96 CI=[2.77, 5.66], P<0.0001; age between 65 and 75: OR=1.69 CI=[1.19, 2.40], P=0.0032 when compared to those aged 45–65 years). Entries for simultaneous (OR 2.23, CI=[1.69, 2.94], P<0.0001) and staged (OR 2.09 CI=[1.28; 3.41], P=0.0031) BTKAs had a significantly increased odds of perioperative mortality when compared to UTKAs. Health care system related factors associated with increased risk for mortality included only hospital size. Surgeries undertaken in large sized and medium sized hospitals were associated with higher odds of perioperative mortality (large: OR 1.48, CI=[1.16, 1.89], P=0.0015; medium: OR 1.44, CI=[1.10, 1.87], P=0.0075 when compared to small hospital size). No other patient demographic and health care system related factors (hospital location, hospital teaching status, type of insurance, and race) were significantly associated with altered risk of mortality.

The estimate of the impact of overall comorbidity burden on mortality was obtained by logistic regression Model 1 (Table 4). We found that for every unit increase comorbidity index, the odds of perioperative mortality increased by 13.6% (OR 1.136, CI=[1.055, 1.223], P=0.0007). A number of comorbidities detected by logistic regression Model 2 (Table 4) increased the risk of a fatal outcome (Table 5), among which pulmonary circulatory disease was associated with the highest increase in the risk for perioperative mortality (OR 11.75, CI=[9.05, 15.25], P<0.0001). Interestingly, after controlling for covariates, the presence of obesity did not reveal to alter the odds of mortality after TKA.

When controlling for comorbidity severity and other patient and health care system related demographics, a number of procedure related complications and adverse events (logistic regression Model 3 (Table 4)) were associated with an increased risk for perioperative mortality (Table 6). Among admissions with the highest risk for mortality were those whose perioperative course was significant for complications affecting the central nervous (OR 22.77, CI=[14.28, 36.31], P<0.0001), cardiac (OR 14.19, CI=[11.25, 17.91], P<0.0001) and those suffering from shock (OR 15.10, CI=[3.88, 58.81], P<0.0001). Further, the occurrence of pulmonary embolism and Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome increased the risk for mortality by 18- and 15-fold, respectively (OR 17.54 CI=[12.69, 24.22], P<0.0001 and OR 14.61 CI=[10.35, 20.63], P=<0.0001, respectively). The incidence of venous thrombotic events was not associated with a risk adjusted increase in perioperative mortality after TKA (OR 0.93, CI=[0.49, 1.79], P=0.8372).

Patient related factors that increased the risk for perioperative procedure related complications included: male gender (OR 1.41, CI=[1.38, 1.44], P<0.0001), older age (age>75 vs. age in 45–64: OR 1.40, CI=[1.34, 1.46], P<0.0001), and minority race (Black vs. White: OR 1.29, CI=[1.26, 1.39], P<0.0001; Other (excluding Black and Hispanic) vs. White: OR 1.23 CI=[1.15, 1.32], P<0.0001). Entries for simultaneous (OR 1.40, CI=[1.33, 1.47], P<0.0001) and staged (OR 1.66 CI=[1.52, 1.79], P<0.0001) BTKAs had a significantly increased odds of perioperative morbidity when compared to UTKAs; staged BTKAs had a significantly increased odds of perioperative morbidity compared to simultaneously performed BTKAs (OR 1.18, CI=[1.07, 1.30], P=0.0008).

Through the logistic regression Model 4 (Table 4), a set of comorbidities were determined that were associated with increased risk of a procedure related complications (Table 7), among which congestive heart failure (OR 2.01, CI=[1.91, 2.11], P<0.0001), pulmonary circulatory disease (OR 2.88, CI=[2.64, 3.14], P<0.0001), and electrolyte/fluid abnormalities (OR 2.43, CI=[2.35, 2.52], P<0.0001) were associated with the highest odds.

Model Diagnostics

Multicollinearity was found absent for all variables (value inflation factor in the range of 1.01–1.76 and condition index in the range of 21.09). Lower Akaike’s information criterion scores were found for all full models (Table 4). The c-statistic values on both the training dataset and the validation dataset were estimated to be in the range 0.7– 0.8 indicating acceptable discrimination. No significant differences were found between the predicted and observed probabilities of death through Model 1 in both datasets and Models 2, 3 and 4 in the validation dataset for the H–L test. The low p-values for the H–L test for Models 2, 3 and 4 on the training dataset might have indicated that these two models are not well calibrated. However, the H–L test is known to not perform well with large sample sizes such as ours, and thus we are not deeming our model suspect of bad calibration.

Discussion

In this study of nationally representative data collected for the NIS between the years of 1998 and 2006, we found an increased incidence of perioperative complications (9.45% vs. 7.07%, P<0.0001) and in-hospital mortality (0.30% vs. 0.14%, P<0.0001) among hospital admissions undergoing BTKA when compared to UTKA procedures. Procedures performed in a staged approach during the same hospitalization were associated with an increased incidence of most studied in-hospital complications when compared with simultaneous surgeries, and offered no mortality benefit (0.29% for simultaneous and 0.26% for staged BTKA, P=0.2875). Risk factors for in-hospital mortality included: a bilateral procedure, advanced age, male gender and the presence of a number of comorbidities and perioperative complications. In view of the increasing utilization of TKA, and in particular of BTKA among the United States population (11, 28), these findings are of importance to the perioperative physician for better assessment of the chance of morbidity and mortality and better identification of patients at risk. These data help inform patients adequately of related risks before embarking on this by and large elective procedure.

A number of studies published in recent years have concluded that BTKAs are associated with increased rates of mortality and complications when compared to unilateral or procedures staged at different hospitalizations (4, 6). We recently studied data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey from the years 1990 to 2004 and found an in-hospital mortality rate of 0.5% among BTKA versus 0.3% among UTKA recipients. Risk adjusted mortality among patients undergoing BTKA was 3- times higher compared to those receiving a UTKA. Despite younger average age and lower comorbidity burden, rates and risks of procedure-related complications compared with those undergoing UTKA were also increased (7). However, data available in the National Hospital Discharge Survey did not allow for comparison between outcomes of BTKAs performed in one versus different surgical sessions, a limitation also described by Barrett et al. when using Medicare data (12). Further, our previous analysis was limited due to the inherent characteristics and operation of the National Hospital Discharge Survey. Among the constraints were a limited amount of available variables (i.e. limited number of diagnosis codes, patient and hospital characteristics), and an estimated sample based on only 1% of the actual national in-hospital population (compared to the 20% sample used in the NIS), thus limiting statistical power when studying low incidence outcomes.

While providing extremely valuable information, previous studies addressing the issue of mortality after BTKA are limited by relatively small sample sizes, use of single institution data, and observation periods that far exceed the perioperative period, thus introducing variables that are beyond the control of the perioperative physician (13, 14). The combination of the fact that BTKAs are undoubtedly a more invasive procedure and most fatal and near fatal outcomes occur early after surgery (14, 29, 30) suggests that focusing on the immediate perioperative period may be appropriate to study procedure related mortality in this setting and has been advocated by others (13).

A number of authors have addressed the question of mortality and complications after BTKA during one hospitalization versus staged during different hospitalizations, but a paucity of studies exists on the issue of simultaneous versus staged procedures during the same hospitalization. Thus, the practice of performing staged procedures during the same hospitalization in the desire reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity (4, 6) while maintaining the advantages of a bilateral procedure (1, 2), remains largely based on anecdote. In a study including 267 patients that underwent BTKA during the same hospitalization, Sliva et al. found that bilateral procedures performed 4–7 days apart were associated with higher risk of mortality and morbidity when compared to simultaneously performed procedures (16). However, only four patients experienced a complication in these two groups pointing out the difficulties of studying low incidence events with institutional data. When further examining the time interval between BTKAs performed during the same hospitalization, Wu et al. recently found no difference in outcomes when procedures were performed 2 or 7 days apart (17), but the authors pointed out that the lack of power secondary to their small sample size of 79 patients was a major limitation.

The availability of nationally representative data and a relatively large sample population allowed us to overcome this particular limitation. When examining the incidence of perioperative complications we were able to confirm the results of previous studies that found an increased rate of adverse events after BTKA versus UTKA. Further, staged procedures were associated with higher rates of most complications than simultaneously performed surgeries. However no difference in in-hospital mortality was found between the two approaches. Reasons for this discrepancy have to remain speculative and causal relationships cannot be studied with data available in the NIS. One explanation may be the coincidence of the second procedure with the peak of metabolic injury and the incidence of most in-hospital complications including myocardial infarctions, arrhythmias, venous thrombotic events etc. on the first few post operative days (29, 30), suggesting a double hit phenomenon.

Having determined that a staged versus simultaneous approach during the same hospitalizations may not offer any mortality benefit and may even lead to increased morbidity, the question remains about the optimal timing of the second TKA. Unfortunately our data source did not allow us to study this issue as patients cannot be followed during different hospitalizations using data available in the NIS. It must be noted that Ritter et al. showed a mortality benefit for a staged versus simultaneous procedure when waiting as little as 6 weeks between surgeries (0.99% versus 0.48%) with a rate compared to UTKAs after 3 months (approximately 0.3%) (31).

We identified a number of risk factors for in-hospital mortality after TKA. In addition to male gender and advanced age, which have been reported as risk factors for mortality after TKA in the past (7,14), increasing overall comorbidity burden and the presence of number of specific comorbidities were associated with an independently increased risk of perioperative mortality in this study. Increased comorbidity burden and mortality among joint arthroplasty patients has been correlated by Rauh et al. in the past (32). The diseases linked with the highest risk for a fatal outcome were pulmonary circulatory disease, metastatic cancer, renal disease and congestive heart failure. Our results would suggest that patients with these diseases should therefore not be considered candidates for BTKA. Although medical treatment before surgery may yield optimization of the patient’s condition it cannot be concluded from this study if this intervention would modify risk for these overwhelmingly difficult to treat conditions.

As expected, a number of perioperative complications were independently associated with postoperative morbidity and mortality. In addition to perioperative shock, complications affecting the central nervous system and pulmonary embolism increased the risk for fatal outcome the most. Pulmonary embolism has long been recognized as a major problem after lower extremity arthroplasty (7, 22) and much effort has been devoted to prevent it (17, 32).

Our study is limited by a number of factors inherent to secondary data analysis of large administrative databases. As such, clinical information (i.e. type of anesthesia, amount of blood loss, length of surgery etc.) available in the NIS is limited and our analysis must be interpreted in this context. Because of the nature of the NIS, only in-patient data are available and thus complications and events after discharge are not captured. Furthermore, readmissions cannot be discerned from this database. Thus, conclusions should be limited to the acute perioperative setting with the notion that mortality and complications are likely underestimated. While it cannot be excluded that the entry of complications or comorbidities may be subject to some form of coding or reporting bias, there is no reason to believe that reporting should differ between procedure types, thus exposing both BTKA and UTKA procedures to the same bias within the same data collection construct. Comparative analysis should therefore be less likely affected by such bias. Further, it is not likely that a “hard” outcome such as mortality should be subject to this form of bias and this is one of the reasons why it was chosen as an end point in this study. In an additional validation step of our data source, we were able to find concordant in-hospital mortality rates in our study (0.15%) with that recently reported by Pulido et al. in 5173 primary total knee arthroplasty patients (0.12%) between 2000 and 2006 (33), thus allowing for a comparative capture time frame and years of observation.

Identification of the timing of BTKA procedures was not possible in approximately one fourth of entries. The reason for this is that approximately one third of states contributing to NIS do not provide information on the procedure dates of multiple procedures, thus it was not possible to include all BTKA procedures in our analysis of staged versus simultaneous surgeries. However, the conclusions from the regression models did not change when treating the missing entries as either staged or simultaneous. Further, the demographics of the missing entries followed that of the general BTKA group, thus offering assurance of the robustness of our data.

An additional limiting factor is the bias associated with the retrospective nature of our study. Nevertheless, because of the availability of data from a large, nationally representative sample, this type of analysis may provide a more accurate estimate of events surrounding TKA than various prospective studies that are limited in sample size and thus lack the ability to capture low-incidence outcomes.

In conclusion, using a nationally representative database we determined that BTKA carried an increased adjusted risk of in-hospital mortality and greater incidence of in-hospital complications when compared to UTKA procedures. Staging of BTKA during the same hospitalization does not offer any mortality benefit and may be associated with an increase in complications. More studies are needed to answer if there are conditions (center selection, patient subpopulations) under which this procedure can be performed without increased risk. Until such data exist the performance of BTKA during one hospitalization (staged or simultaneous) cannot be recommended based on our findings. If performed however, careful patient selection for BTKA and in depth discussion about risks and alternatives with the patient cannot be overemphasized. Risk factors identified in this analysis may be used to gauge the perioperative mortality risk for individual patients and the presence of significant diseases should lead to exclusion of patients as candidates for BTKA.

Acknowledgments

Financial disclosure: This study was performed with funds from the Hospital for Special Surgery Anesthesiology Young Investigator Award provided by the Department of Anesthesiology at the Hospital for Special Surgery (Stavros G. Memtsoudis) and Center for Education and Research in Therapeutics (CERTs) (AHRQ RFA-HS-05-14) and Clinical Translational Science Center (CTSC) (NIH UL1-RR024996) (Yan Ma and Madhu Mazumdar).

Footnotes

HCUP Databases. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). July 2008 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp. Last modified 7/11/2008 Last accessed 5/14/2009.

Introduction to the HCUP National Inpatient Sample (NIS) 2006. May 2008 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/2006NIS_INTRODUCTION.pdf. Last modified 5/14/2008. Last accessed 5/14/2009.

Publications from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project Databases. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). http://www.ahrq.gov/data/hcup/hcupref.htm. Last accessed 5/14/2009.

HCUP Comorbidity Software. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). April 2009 Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/comorbidity/comorbidity.jsp. Last modified 4/24/2009. Last accessed 5/14/2009.

No conflicts of interest arise from any part of this study for any of the authors.

Summary Statement: Bilateral knee arthroplasty carries an increased risk of perioperative morbidity and mortality compared to unilateral procedures. Staging bilateral procedures during the same hospitalization caries no mortality benefits and is associated with increased morbidity.

References

- 1.Kovacik MW, Singri P, Khanna S, Gradisar IA. Medical and financial aspects of same-day bilateral total knee arthroplasties. Biomed Sci Instrum. 1997;33:429–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reuben JD, Meyers SJ, Cox DD, Elliott M, Watson M, Shim SD. Cost comparison between bilateral simultaneous, staged, and unilateral total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:172–179. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(98)90095-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stubbs G, Pryke SE, Tewari S, Rogers J, Crowe B, Bridgfoot L, Smith N. Safety and cost benefits of bilateral total knee replacement in an acute hospital. ANZ J Surg. 2005;75:739–746. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2005.03516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stefánsdóttir A, Lidgren L, Robertsson O. Higher Early Mortality with Simultaneous Rather than Staged Bilateral TKAs: Results From the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:3066–3070. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0404-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luscombe JC, Theivendran K, Abudu A, Carter SR. The relative safety of one-stage bilateral total knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2009;33:101–104. doi: 10.1007/s00264-007-0447-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Restrepo C, Parvizi J, Dietrich T, Einhorn TA. Safety of simultaneous bilateral total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:1220–1226. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Memtsoudis SG, González Della Valle A, Besculides MC, Gaber L, Sculco TP. In-hospital complications and mortality of unilateral, bilateral, and revision TKA: Based on an estimate of 4,159,661 discharges. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:2617–2627. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0402-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hooper GJ, Hooper NM, Rothwell AG, Hobbs T. Bilateral Total Joint Arthroplasty: The Early Results from the New Zealand National Joint Registry. J Arthroplasty. 2008 Dec 2; doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.09.022. (epub-ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urban MK, Chisholm M, Wukovits B. Are Postoperative Complications More Common with Single-Stage Bilateral (SBTKR) Than with Unilateral Knee Arthroplasty: Guidelines for Patients Scheduled for SBTKR. HSS J. 2006;2:78–82. doi: 10.1007/s11420-005-0125-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Katz JN, Barrett J, Mahomed NN, Baron JA, Wright J, Losina E. Association Between Hospital and Surgeon Procedure Volume and the Outcomes of Total Knee Replacement. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 2004;86:1909–1916. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200409000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memtsoudis SG, Besculides MC, Reid S, Gaber-Baylis LK, González Della Valle A. Trends in Bilateral Total Knee Arthroplasties: 153,259 Discharges between 1990 and 2004. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1568–1576. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0610-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barrett J, Baron JA, Losina E, Wright J, Mahomed NN, Katz JN. Bilateral total knee replacement: Staging and pulmonary embolism. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:2146–2151. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parvizi J, Sullivan TA, Trousdale RT, Lewallen DG. Thirty-day mortality after total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:1157–1161. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200108000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ritter MA, Harty LD, Davis KE, Meding JB, Berend M. Simultaneous bilateral, staged bilateral, and unilateral total knee arthroplasty: A survival analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:1532–1537. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200308000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill GS, Mills D, Joshi AB. Mortality following primary total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:432–435. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sliva CD, Callaghan JJ, Goetz DD, Taylor SG. Staggered bilateral total knee arthroplasty performed four to seven days apart during a single hospitalization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:508–513. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wu CC, Lin CP, Yeh YC, Cheng YJ, Sun WZ, Hou SM. Does different time interval between staggered bilateral total knee arthroplasty affect perioperative outcome? A retrospective study. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:539–542. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bateman BT, Schumacher HC, Wang S, Shaefi S, Berman MF. Perioperative acute ischemic stroke in noncardiac and nonvascular surgery: Incidence, risk factors, and outcomes. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:231–238. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318194b5ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosero EB, Adesanya AO, Timaran CH, Joshi GP. Trends and outcomes of malignant hyperthermia in the United States, 2000 to 2005. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:89–94. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318190bb08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen Y, Silverstein JC, Roth S. In-hospital complications and mortality after elective spinal fusion surgery in the united states: A study of the nationwide inpatient sample from 2001 to 2005. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2009;21:21–30. doi: 10.1097/ANA.0b013e31818b47e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harrell F, Lee KL, Mark DB. Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med. 1998;15:361–387. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361::AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. A goodness-of-fit test for the multiple logistic regression model. Commun Stat. 1980;A10:1043–1069. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pepe MS. The statistical evaluation of medical tests for classification and precision. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 66–94. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: John Wiley & Son, Inc; 2000. p. 162. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kramer AA, Zimmerman JE. Assessing the calibration of mortality benchmarks in critical care: The Hosmer-Lemeshow test revisited. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2052–2056. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275267.64078.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Memtsoudis SG, Gonzalez Della Valle A, Besculides MC, Gaber L, Laskin R. Trends in demographics, comorbidity profiles, in-hospital complications and mortality associated with primary knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24:518–527. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.01.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Parvizi J, Mui A, Purtill JJ, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Total joint arthroplasty: When do fatal or near-fatal complications occur? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:27–32. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mantilla CB, Horlocker TT, Schroeder DR, Berry DJ, Brown DL. Frequency of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, and death following primary hip or knee arthroplasty. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1140–1146. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200205000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ritter M, Mamlin LA, Melfi CA, Katz BP, Freund DA, Arthur DS. Outcome implications for the timing of bilateral total knee arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;345:99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rauh MA, Krackow KA. In-hospital deaths following elective total joint arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 2004;27:407–411. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-20040401-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pulido L, Parvizi J, Macgibeny M, Sharkey PF, Purtill JJ, Rothman RH, Hozack WJ. In Hospital Complications After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23:139–145. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]