Abstract

Objective

To test whether the Tailored Activity Program for at-home dementia patients reduces neuropsychiatric behaviors and caregiver burden.

Method

A prospective, two-group controlled pilot study with 60 dyads randomized to treatment or wait-list control. Dyads were interviewed at baseline and 4 months (trial endpoint); control participants then received intervention and were reassessed 4 months later. The 8-session occupational therapy intervention involved neuropsychological and functional testing from which activities were customized and instruction in use provided to caregivers.

Results

At 4-months, compared to controls, intervention caregivers reported reduced frequency of behaviors (p = .010; Cohen’s d = .72), specifically for shadowing (p = .003, Cohen’s d = 3.10) and repetitive questioning (p = .23, Cohen’s d = 1.22); greater activity engagement (p = .029, Cohen’s d = .61); and ability to keep busy (p = .017, Cohen’s d = .71). Also, fewer intervention caregivers reported agitation (p = .014, Cohen’s d = .75) or argumentation (p = .010, Cohen’s d = .77). Caregiver benefits included fewer hours doing things (p = .005, Cohen’s d = 1.14) and being on duty (p = .001, Cohen’s d = 1.01), greater mastery (p = .013, Cohen’s d = .55), self-efficacy (p = .011, Cohen’s d = .74), and use of simplification techniques (p = .023, Cohen’s d = .71). Wait-list control participants showed similar benefits for behavioral frequency following intervention.

Conclusions

Results suggest clinically-relevant benefits for both dementia patients and caregivers, with treatment minimizing the occurrence of behaviors that commonly trigger nursing home placement.

Keywords: Dementia caregiving, Activity engagement, Disruptive behaviors

Objectives

Over 5.1 million Americans have dementia, a progressive and irreversible neurodegenerative disorder, with this number expected to increase by 2050 to over 14 million.(1) Neuropsychiatric behaviors such as apathy, depressed affect, lability, agitation, and aggressiveness are common occurrences, with most patients manifesting these behaviors over the course of the disease.(2, 3, 4) Behaviors are the most challenging aspect of caregiving, contributing to caregiver distress, depression, increased care costs, and risk for nursing home placement. (5, 6, 7, 8) There are few tested interventions to minimize behavioral occurrences. Recent research has shown that pharmacological approaches may not be effective and may cause harm (9, 10, 11). A few caregiver intervention studies report minimal behavioral benefits (12, 13, 14, 15), with most studies not examining patient symptom reduction. Thus, developing and testing non-pharmacological approaches to address behaviors is an important public health priority as articulated in recent position statements by the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry (16) and Annals of Internal Medicine. (17)

One promising approach is activity. Research shows that purposeful activity results in reduced depressive and agitated behaviors. (18, 19) However, studies have focused exclusively on nursing home residents, involved small sample sizes, used non-experimental designs, or have not tested systematic approaches to developing activities. Lack of research on community-living patients is significant given that the home is the primary care setting for this population.

This pilot controlled study evaluates an activity-based intervention, the Tailored Activity Program (TAP) that seeks to reduce behavioral disturbances by identifying patients’ preserved capabilities and devising activities that build on them. The trial tested whether tailored activities reduced behavioral occurrences in dementia patients and caregiver burden and enhanced patient engagement, caregiver mastery, self-efficacy, and use of simplification strategies to manage behaviors. Also, because the intervention required caregiver involvement, we evaluated whether caregiver depressive symptoms moderated dementia patient and caregiver outcomes.

Using a two-group randomized, parallel design, 60 dyads (dementia patients and their caregivers) were assigned to treatment or wait-list control. Treatment group participants received TAP, and all dyads were reassessed at four months from baseline. At that point, wait-list controls received the same intervention and were retested four months later (eight months from baseline). This design allowed for estimation of effect sizes using a randomized two-group design at four months, confirmation of treatment gains for wait-listed participants from four to eight months, and evaluation of program acceptability for all 60 dyads. We hypothesized that relative to controls at four months, intervention caregivers would report reduced behavioral occurrences and enhanced activity engagement for dementia patients and reduced caregiver burden, and enhanced mastery, confidence and skill in using activities. We predicted similar benefits for wait-list controls at eight months.

Methods

Study Sample and Procedures

Participants were recruited between 2005 and 2006 through media announcements and mailings by social service agencies. Interested caregivers contacted the research office, were explained study procedures and administered a brief telephone eligibility screen. Eligibility criteria concerned dementia patients and caregivers. Dementia patients were English-speaking, had a physician diagnosis or Mini-mental State Examination (MMSE) score < 24 (20), able to feed self and participate in at least two self-care activities (bathing, dressing, grooming, toileting, or transferring from bed to chair). Caregivers were English-speaking, 21 years of age or older, living with the patient planning to live in the area for eight months, willing to learn activity use, and providing ≥4 hours of daily care. Dyads were excluded if patients had schizophrenia, bi-polar disorder, or dementia secondary to head trauma, had an MMSE score = 0 and were bed-bound (confinement to bed/chair for at least 22 hours daily) and non-responsive (unable to understand short commands). Dyads were also excluded if caregivers were involved in another study or seeking nursing home placement. Finally, dyads were ineligible if either person was terminally ill, in active cancer treatment, or had more than 3 hospitalizations in the past year. Criteria were designed to enroll patients at the moderate stage, when behaviors occur most frequently.

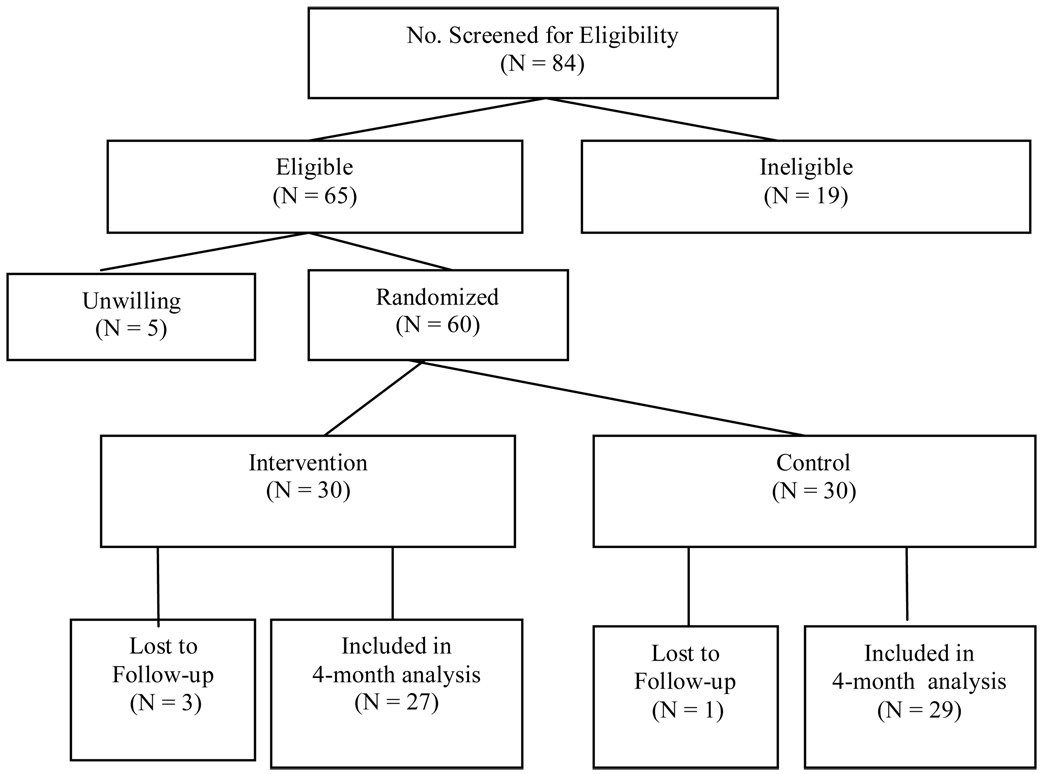

As Figure 1 shows, 84 caregivers were telephone screened, 65 (77%) were eligible, and 60 (92%) were willing to participate. Within 48 hours of baseline, dyads were randomized by the project director using random permuted blocks to control for possible changes in subject mix over time. The blocking number, developed by the project statistician, remained unknown to others. All dyads were subsequently interviewed at 4 months by trained interviewers masked to group assignment and with no intervention role. Of 60 dyads at baseline, only 4 (7%) terminated due to patient death.

Figure 1.

Consort Flow Chart of Subject Recruitment and Attrition

Intervention Group

TAP is based on the environmental vulnerability/reduced stress-threshold model, which posits that with disease progression, dementia patients become increasingly vulnerable to their environment and experience lower thresholds for tolerating stimuli, which can result in behavioral disturbances. (21, 22) The intervention addressed this vulnerability by matching activities to cognitive and functional capabilities, and previous roles, habits and interests.

TAP involved 8 sessions, six home visits (90 minutes each) and two (15 minute) telephone contacts by occupational therapists (OT) over 4 months. Contacts were spaced to provide caregivers opportunities to practice using activities independently. In the first two home sessions, interventionists met with caregivers, introduced intervention goals, used a semi-structured investigator-developed interview to discern daily routines, and the Pleasant Event Schedule to identify previous and current activity interests.(23) Interventionists observed dyadic communication and home environmental features and assessed dementia patients using the Dementia Rating Scale (24) and Allen’s observational craft-based assessments (leather lacing, placemat task, sensory-based tests). (25, 26, 27)

In subsequent sessions, interventionists identified three activities and developed 2–3 page written plans (Activity Prescriptions) for each. Each prescription specified patient capabilities, an activity (completing a puzzle form board) and goal (engage in activity for 20 minutes each morning after breakfast) and specific implementation techniques (Appendix A). Activities ranged in complexity from multi-step (making salad, simple woodworking) to one-to-two step (sorting beads, playing catch with grandchild), to sensory-based (viewing videos, listening to music). Caregivers, and when appropriate dementia patients, chose one activity prescription to focus on first. The prescription was reviewed and the activity introduced through role-play or direct demonstration with patients. Caregivers were also instructed in stress reducing techniques (deep breathing) to help establish a calm emotional tone. Caregivers practiced using the activity between visits. Once an activity was mastered, another was introduced. In each session, prescriptions were reviewed and modified if necessary. As caregivers mastered activity use, interventionists generalized simplification strategies to care problems and instructed how to downgrade activity complexity to prepare for future declines in capability.

Measures

Background characteristics of dyads included age, income, education, and years providing care. These were measured as continuous variables. Gender, relationship to dementia patient (spouse, non-spouse), race (white, non-white) and marital status (currently married/not married) were measured as dichotomous variables.

Dementia Patient Outcomes

The primary outcome was the occurrence of each of 24 behaviors, 16 from the Agitated Behaviors in Dementia Scale (28), 2 (repetitive questioning, hiding/hoarding) from the Revised Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist (29), 4 (wandering, incontinent incidents, shadowing, boredom) from previous research showing these behaviors as common and distressful (13), and 2 “others” identified by families that could not be coded elsewhere. For each behavior, caregivers indicated occurrence (yes/no) and, if yes, number of times in the past month. Two indices were created: number of behaviors occurring (α=.86) and mean frequency of occurrence (main study endpoint). Behaviors reported by caregivers as occurring “constantly” (repetitive questioning) were assigned a score of 300, representing the largest number of reported occurrences across all subjects and behaviors (except for one subject who specified “600” times for one behavior). Two caregivers reported one or more behaviors as “constant” at baseline and seven did so at 4 months. We tested other coding schemes for the “constant” value including recoding the 600 score to 300, and in separate analyses, recoding all “constants” to 600. Since outcomes were similar regardless of coding, we report results for the original coding described above.

We used the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD), a 19-item measure designed to rate depressive symptoms (mood signs, ideational disturbances). (30) The CSDD was administered to dementia patients and caregivers each of whom respond to items independently. Composite scores per item were based on combined ratings (0=not present; 1= present; 2=severe) of caregiver and patient. Scores represented the sum of composite scores across 19 items (α=.76).

Activity engagement was measured using a 5-item, investigator-developed index of caregiver report of patient in past two weeks (“Enjoyed doing activities” “Showed signs of pleasure/enjoyment”) from 1=“Never” to 3=“Often.” Scores represented ratings across five items (with one reverse coded) with higher scores indicating greater engagement (α=.54).

We used the Quality of Life-AD scale, on which caregivers rated their family members’ quality of life along 12 dimensions (energy, mood, memory, ability to keep busy, have fun). Responses ranged from 1=“Poor” to 4=“Excellent”. Scores represented mean response with higher scores indicating better life quality (α=.72). (31)

Caregiver Outcomes

We included mastery, a 5-item Likert (1=never to 5=always) scale (α=.70) (32); subjective burden measured as upset with behaviors (1=no upset to 8=extreme upset) (29); the 10-item Zarit Burden Scale (α=.89) (33); objective burden as measured caregiver estimate of real time spent “on duty” and “doing things” for dementia patients. (34)

Caregiver depression was measured by the 20-item CES-D scale with symptoms rated as occurring in the past week (0=less than one day to 3=five-seven days). Scores represented summed responses, with higher scores indicating greater symptomatology (α=91). (35)

Confidence using activities during the past month (0=not confident to 10=very confident) was measured by 5 investigator-developed items. Scores were averaged across items, with higher mean ratings indicating greater confidence (α=.72).

Skill enhancement was measured using the 19-item Task Management Strategy Index. Caregivers indicated how often strategies (cueing, simplifying routines) were used (1=never to 5=always). A mean task strategy use score was calculated, with high scores indicating greater use (α=.80). (36)

Treatment Documentation

Interventionists documented the number of completed sessions, time spent, who participated (caregiver, patient), and number of activities introduced. At the conclusion of intervention, interventionists rated (not at all, somewhat, very much) the extent to which patients appeared agitated, resisted attempts to participate, and expressed or showed pleasure; and extent to which caregivers indicated the intervention was useful, demonstrated understanding of strategies, reported using strategies, and indicated strategies had no effect or made matters worse.

Data Analysis

Descriptive data included sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race, education, relationship), health conditions, self-rated health, economic well-being, cognitive status, depressive symptoms, ADL and IADL physical functioning and treatment characteristics. Chi-square and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were used to compare experimental and control dyads on characteristics. Means, standard deviations and ranges for outcome measures and treatment characteristics were computed.

Main treatment effects at four months were examined using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and logistic regression procedures. To increase precision of treatment comparisons, baseline values, cognitive status and number of functional dependencies of patient, caregiver age, gender, education and relationship to patient were selected a priori as covariates based on previous research showing significant associations between these factors and outcomes. Cohen’s d was determined as a measure of effect size.

The distribution of residuals from the ANCOVAs was examined for outcomes and found to be somewhat skewed for behavior frequency overall, frequency of five behaviors (agitation, refusing care, repetitive questioning, hoarding and shadowing), and two vigilance items (hours doing things and hours on duty). Log transformations improved distributions.

The numbers of behaviors were coded as any occurrence versus no occurrence and analyzed using logistic regression, with independent variables the same as described above for ANCOVAs.

To evaluate differential effects at four months based on caregiver baseline depressive symptoms we used a similar analytic strategy as for the main effect models. ANCOVAs and logistic regressions procedures were used in which baseline values, dementia patient cognitive status and dependencies, caregiver age, gender, education and relationship to patient were covariates. We then added an interaction term (treatment group by baseline CES-D score).

To evaluate whether control group participants derived similar benefits to the experimental group after receiving TAP, we compared four (T2) to eight (T3) month scores of controls to baseline (T1) to four (T2) month scores of experimental group participants on statistically significant outcomes from the main analyses, using the same methods as described. We anticipated that the magnitude of the difference between experimental and control group treatment effects would be similar and thus not statistically significant. SPSS version 15.0 was used with significance level set at .05. All analyses were two-sided. Analyses followed intention to treat such that all subjects providing data were included in analyses regardless of study participation level.

Results

Dementia patients were primarily male (57%) and White (77%) and had a mean age of 79 years. Their MMSE score was 11.6, and they were on average dependent in eight instrumental and five basic daily living activities. Caregivers were primarily female (88%), White (77%), high school graduates (56%), and spouses (62%), with a mean age of 65 years (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Sample

| Characteristics | Wait-list (n = 30) |

Experimental (n = 30) |

Total (n = 60) |

Range | χ2 | Z | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dementia Patient | |||||||

| Age (Mean (SD)a | 80.8 (9.5) | 78.0 (9.2) | 79.4 (9.4) | 56.0 – 96.2 | −1.30 | .192 | |

| Gender (%) | 1.07 | .297 | |||||

| Male | 63.3 | 50.0 | 56.7 | ||||

| Female | 36.7 | 50.0 | 43.3 | ||||

| Race (%) | 1.16 | .559 | |||||

| White | 80.0 | 73.3 | 76.7 | ||||

| African American | 20.0 | 23.3 | 21.7 | ||||

| Other | 0.0 | 3.3 | 1.6 | ||||

| Education (%)b | 1.16 | .559 | |||||

| ≤ HS | 60.7 | 48.3 | 54.4 | ||||

| ≤ College | 25.0 | 37.9 | 31.6 | ||||

| Graduate degree | 14.3 | 13.8 | 14.0 | ||||

| MMSE (Mean (SD)c | 12.2 (8.8) | 11.0 (7.3) | 11.6 (8.1) | 0.0 – 27.0 | −.72 | .473 | |

| CSDD (Mean (SD) | 8.1 (4.5) | 9.2 (5.1) | 8.7 (4.8) | 1.0 – 20.0 | −.68 | .495 | |

| ADL | 4.37 (2.1) | 4.6 (2.3) | 4.5 (2.2) | 0.0 – 7.0 | −.63 | .529 | |

| IADL | 7.4 (1.2) | 7.8 (.5) | 7.6 (.9) | 3.0 – 8.0 | −.84 | .401 | |

| Self-rated health | 3.2 (1.0) | 3.2 (.9) | 3.2 (.9) | 1.0 – 5.0 | −.23 | .815 | |

| Caregiver | |||||||

| Age (Mean (SD) | 67.9 (10.6) | 62.8 (11.3) | 65.4 (11.1) | 47.2 – 89.7 | −1.99 | .047 | |

| Gender (%) | 1.46 | .228 | |||||

| Male | 6.7 | 16.7 | 11.7 | ||||

| Female | 93.3 | 83.3 | 88.3 | ||||

| Race (%) | 1.16 | .559 | |||||

| White | 80.0 | 73.4 | 76.7 | ||||

| African American | 20.0 | 23.3 | 21.7 | ||||

| Other | 0.0 | 3.3 | 1.6 | ||||

| Education (%)a | .263 | .877 | |||||

| ≤HS | 24.2 | 30.0 | 27.2 | ||||

| ≤College | 58.6 | 53.3 | 55.9 | ||||

| Graduate degree | 17.2 | 16.7 | 16.9 | ||||

| Relationship to Patient (%) | 1.76 | .184 | |||||

| Spouse | 70.0 | 53.3 | 61.7 | ||||

| Non-spouse | 30.0 | 46.7 | 38.3 | ||||

| Financial Difficulty (Mean (SD) | 2.0 (1.0) | 1.7 (.8) | 1.9 (.9) | 1.0 – 4.0 | −1.30 | .195 | |

| Health (Mean (SD) | |||||||

| Self-rated health | 9.0 (2.0) | 1.7 (.8) | 9.0 (2.3) | 3.0 – 12.0 | −.33 | .742 | |

| Health behaviors | 3.0 (1.5) | 2.8 (1.7) | 2.9 (1.6) | 0.0 – 5.0 | −.49 | .625 | |

Note: MMSE = Mini Mental Status Examination; CSDD = Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia; ADL = Activities of Daily Living; IADL = Instrumental ADL

N = 59;

N = 57;

N = 58

Treatment Implementation

For the intervention group, nearly eight contacts were completed, with approximately 6 sessions face-to-face and 2 by telephone. The average time spent was 1 hour in each home visit and 15 minutes for telephone contacts. Consistent with intervention intent, most contacts (M =5.13, SD=1.36) involved both patients and caregivers with an average of 2.4 (SD=1.1) activities introduced. Wait-list controls had a similar implementation profile upon treatment receipt (Table 2). An average of $70 per participant was spent (range=0 to $129) for activity-related materials (activity boards, enlarged games, beads, organizing bins, task lighting).

Table 2.

Treatment Implementation Characteristics for Experimental and Wait-list Control Participants (N = 58)

| Characteristics | Wait-list Control (n = 30) |

Experimental (n = 30) |

t (df= 56) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of contacts | 7.50 (1.04) |

7.47 (1.31) |

.107 | .915 |

| Number face-to-face contacts | 5.46 (1.00) |

5.50 (1.17) |

.366 | .716 |

| Number phone contacts | 2.15 (0.86) |

2.07 (0.75) |

.107 | .915 |

| Number contacts with caregiver only | 7.50 (1.04) |

7.43 (1.30) |

.214 | .831 |

| Number contacts with dementia patient | 5.39 (1.13) |

5.17 (1.37) |

.683 | .497 |

| Number contacts with both present | 5.36 (1.16) |

5.13 (1.36) |

.672 | .504 |

| Number of activities introduced | 2.39 (1.20) |

2.41 (1.18) |

.066 | .947 |

| Length of face-to-face contacts (hours: minutes) | 1:18(0:25) | 1:10(−:24) | .369 | .713 |

| Length of telephone contacts (hours: minutes) | 0.15 (0:08) | 0:15 (0:06) | .150 | .881 |

Note: df = degrees of freedom

4 Month Patient Outcomes

We found a treatment effect for frequency of behavioral occurrences (p=.009; Cohen’s d=.72, Table 3), with reductions in shadowing (adjusted mean difference =-1.00, CI = −1.36, −.64; p = .003, Cohen’s d = 3.10) and repetitive questioning (adjusted mean difference =−.49, CI = −.90, −.07; p=.023, Cohen’s d=1.22) reaching statistical significance (not shown on Table 3). Also, there was a slight decrease in the number of reported behaviors for TAP participants compared to controls, for whom the number of behaviors increased, but the difference did not reach statistical significance. We did find statistically significant reductions in the number of experimental caregivers that reported agitation (p=.014, Cohen’s d=.75) and argumentative behaviors (p=.010, Cohen’s d=.77) compared to controls. Furthermore, experimental caregivers reported greater activity engagement (p=.029, Cohen’s d=.61), ability to keep busy (p=.017, Cohen’s d=.71), and a trend toward overall improved life quality (p=.095). We did not find an effect for depressed mood (Table 3).

Table 3.

Outcomes for Experimental and Wait List Control Group Dementia Patients at Four Months (N = 56)a

| Experimental (N = 27) | Control (N = 29) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 4-Months | Baseline | 4-Months | |||||

| Dependent Variable | M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

Adjusted Mean Effect at 4 months |

p | 95% CI | d |

| Behavioral Occurrences | 30.5 (30.3) | 18.8 (17.6) | 41.5(70.5) | 60.8 (85.3) | −.32b | .009 | −.55, −.09 | .72 |

| Number of Behaviors | 8.0 (3.8 | 7.2 (4.1) | 7.5 (4.5) | 7.7 (3.7) | −.98 | .249 | −2.67, .71 | |

| CSDD | 9.2 (5.1) | 9.0 (4.6) | 8.1 (4.5) | 8.7 (4.7) | −1.10 | .340 | −3.39, 1.19 | |

| Activity engagement | 2.1 (.4) | 2.3 (.3) | 1.9 (.4) | 2.0 (.4) | .22 | .029 | .02, .41 | .61 |

| Pleasure in recreation | 2.4 (.6) | 2.6 (.5) | 2.2 (.7) | 2.1 (.7) | .38 | .045 | .01, .74 | .64 |

| Quality of Life Scale | 2.2 (.3) | 2.4 (.4) | 2. (.4) | 2.1 (.5) | .18 | .095 | −.03, .40 | |

| Ability to keep busy | 1.6 (.9) | 2.2 (.7) | 1.7 (.8) | 1.6 (.9) | .56 | .017 | .11, 1.01 | .71 |

| % | Wald | |||||||

| B. Specific Behaviorsc | 95% CI for | |||||||

| Agitatedd | 30.4 | −2.89 | 1.18 | 6.00 | .06 | .014 | .01, .56 | .75 |

| Arguingd | 44.6 | −2.51 | .98 | 6.55 | .08 | .010 | .01, .56 | .77 |

Note: CSDD = Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia

All analyses were adjusted for baseline value, care recipient cognitive status (MMSE) and number of ADL dependencies, caregiver age, gender, education, relationship to the care recipient.

Adjusted mean effect and confidence intervals are based on log transformed values.

Binary logistic regressions were used to analyze the behavior data; values are for main effects of treatment.

Hosmer and Lemeshow test of goodness of fit = .685 and .638, respectively.

4 Month Caregiver Outcomes

Caregivers in the experimental group reported fewer hours doing things for patients (p=.005, Cohen’s d=1.14), approximately one hour less, whereas control group caregivers reported two hours more by four months. Experimental caregivers also reported fewer hours on duty (p=.000, Cohen’s d=1.01), approximately five hours less, whereas control participants reported about two hours more. Also, experimental caregivers reported greater mastery (p=.013, Cohen’s d=.55), enhanced self-efficacy using activities (p=.011, Cohen’s d=.74), and greater use of simplification techniques (p=.023, Cohen’s d=.71) compared to controls (Table 4). We did not find a statistically significant treatment effect for subjective burden.

Table 4.

Outcomes for Experimental and Wait List Control Group Caregivers at Four Months (N = 56)a

| Experimental (N = 27) | Control (N = 29) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 4-Months | Baseline | 4-Months | |||||

| Dependent Variable | M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

M (SD) |

Adjusted Mean Effect at |

p | 95% CI | d |

| A. Subjective Burden | ||||||||

| Behavior Upset | 4.5 (1.9) | 4.5 (1.8) | 4.6 (3.0) | 4.8 (2.5) | −.01 | .984 | −1.21, 1.18 | |

| Burden | 21.0 (9.0) | 20.3 (8.8) | 21.3 (9.2) | 20.6 (10.4) | .75 | .715 | −3.36, 4.85 | |

| CES-D | 14.6 (11.0) | 13.1 (9.4) | 13.2 (9.6) | 14.3 (10.2) | −.74 | .676 | −4.31, 2.82 | |

| B. Objective Burden | ||||||||

| Hours doing for patient | 6.3 (4.3) | 5.4 (2.5) | 6.2 (3.3) | 8.6 (5.7) | −.22 b | .005 | −.36, −.07 | 1.14 |

| Hours feel on duty | 18.2 (7.3) | 13.4 (7.6) | 15.5 (7.7) | 17.6 (7.1) | −.25 b | .001 | −.37, −.12 | 1.01 |

| C. Caregiver Skill | ||||||||

| Mastery | 3.4 (.5) | 3.7 (.6) | 3.7 (.6) | 3.7 (.6) | .34 | .013 | .08, .60 | .55 |

| Confidence Using | 5.4 (1.9) | 7.4 (1.9) | 6.2 (1.7) | 6.4 (2.5) | 1.67 | .011 | .41, 2.94 | .74 |

| Activities Task Simplification |

3.0 (.6) | 3.2 (.5) | 2.8 (.5) | 2.9 (.6) | .25 | .023 | .04, .46 | .71 |

| Strategy Use | ||||||||

Note: CES-D= Center for Epidemiological Scale for Depression

All analyses were adjusted for baseline value, care recipient cognitive status (MMSE), number of ADL dependencies, caregiver age, gender, education, and relationship to the care recipient.

Adjusted mean effect and confidence intervals are based on log transformed values.

Finally, we found that caregiver baseline depressive symptom scores did not moderate treatment outcomes. Depressed (CES-D ≥16) caregivers representing 36.7% of the sample, and non-depressed (CES-D <16) caregivers benefited similarly from TAP on all major outcomes.

Control Group Outcomes Following Treatment

A comparison of adjusted mean effects between experimental (T1–T2) and wait-list controls (T2–T3) showed a similar pattern of benefit for frequency of behaviors (adjusted mean effect = −.25, CI, −.42,.−.08), and two caregiver-related outcomes, hours doing things for patient (adjusted mean effect = −.04, CI, −.16,.07), and mastery (adjusted mean effect = .17, CI, −.07,.41). However, compared to 4-month outcomes for the experimental group, control group participants showed no benefits in engagement level, caregiver hours on duty, confidence or use of simplification strategies.

Acceptability of TAP

For all dyads (N = 60), 69.6% of dementia patients engaged in activity with interventionists “very much” and 30.4% engaged “somewhat”, with 67% expressing or showing pleasure very much, 30.4% showing pleasure somewhat and only 2.2% showing no pleasure at all. In contrast, 6.5% of patients refused participation, 2.2% appeared agitated and 2.2% appeared upset in one or more sessions. Interventionists reported that 84.8% of caregivers indicated the intervention was very useful with 15.2% finding it somewhat useful. Also, 89.1% of caregivers indicated the intervention had a positive effect. Only 10.9% indicated that strategies had no effect or made matters worse. Interventionists also reported that 100% of caregivers demonstrated an understanding of strategies somewhat or very much. Only 2.2% did not use recommended activity strategies.

Conclusions

The results of this controlled pilot study suggest positive benefits and very large symptom reductions as demonstrated by the effect size for patient and caregiver outcomes. As to behaviors, the main outcome, treatment gains were found for the most frequently occurring behaviors (shadowing, repetitive questioning) and for agitation and argumentative behaviors, which research suggests trigger nursing home placement. Additionally, life quality improvements were found such that caregivers reported enhanced ability of their relative to derive pleasure and engage in activities. We did not find that TAP minimized depressed mood in dementia patients, although the change was in the expected direction.

As to caregivers, study findings suggest that TAP significantly reduced objective burden as measured by the amount of time spent in hands-on care, supervision or oversight, although associated subjective appraisals of burden and upset were not affected. This suggests that an intervention which specifically targets subjective appraisals may be desirable to complement the TAP program. However, other important benefits included skill enhancement, mastery, and self-efficacy using activities. Although we did not reduce caregiver depressive symptoms, caregivers reporting depressive symptoms and those who did not at baseline, benefited similarly from TAP. Thus, although the intervention was behaviorally demanding, even distressed caregivers were able to participate and benefit.

Of importance, TAP required 25 hours of interventionist training, and was implemented as intended. It was well tolerated by patients and caregivers alike as suggested by high interventionist ratings of receptivity and enactment. While interventionist ratings are potentially biased, low attrition and high average session participation rates indicate otherwise.

Why does engagement in activities tailored to cognitive capacity and interests of dementia patients result in symptom reduction? One explanation may be that activities fill a void, enhance role identity, and help dementia patients express themselves positively. (36) This may afford control over self-identity, a critical attribute of selfhood that may endure throughout the disease process. (37) The intervention introduced activities that preserved previous roles and identities of individuals (preparing simple meals for homemakers, or craft involvement). Life-long activities were modified by simplifying them to match patient abilities, thereby minimizing frustration and affording positive engagement. The facilitation of self-actualization was illustrated by some patients’ remembering interventionists between sessions that occur weeks apart, creating craft objects for holiday gifts, or expressing a wish to frame the placemat made during the assessment.

Another explanation may be that the intervention reduces allostatic load, defined as overload of sensory and information processing capacity. (38) Recent conceptualizations of behaviors as reflecting the interplay between neurological, social-psychological and environmental factors suggest that external conditions may overload patients’ abilities, which may result in negative consequences. (16, 39, 40) Simplifying the task and the environmental context in which activity occurs, hence “tailoring” activity, may reduce physiological stress responses and agitated-type behaviors.

Caregivers may benefit from TAP in several ways. A significant concern of families is how to occupy their relatives and support self-identity. Caregivers are particularly distressed by their relatives’ apathy and distress. (5, 41). TAP offered activities that provided pleasure, and caregivers observed immediate benefits. Moreover, the assessments provided caregivers with an understanding of the patient’s capacity for making decisions about safety. Finally, caregivers found that activities were pleasurable and easy to implement, and rather than requiring additional time, reduced time in daily care.

Important clinical implications can be derived. The TAP assessment combined neuropsychological testing and performance observations to obtain an understanding of capacity and deficits. Families often under- or over-estimate patient abilities and may benefit from the TAP assessment itself. One recommendation may be for referral to an occupational therapist trained in the TAP assessment to augment neuropsychological testing to inform families of patient capacities. Second, because this program preserves functionality by reducing behavioral disturbances, TAP may be reimbursable under Medicare guidelines and thus a plausible disease management strategy.

In summary, this study provides compelling evidence that a tailored approach that taps residual abilities and previous roles and habits improves life quality in dementia patients. This study identifies a process for customizing activities to abilities and training families in use of activities in daily care. Teaching caregivers activity use has added value by reducing their objective burden and enhancing skills. Given that pilot studies tend to yield large effect sizes (42), and that the control group did not evince benefit in all areas as the experimental group after treatment receipt, it is important to test TAP on a larger scale, validate it with diverse dyads, and examine the underlying physiological mechanisms by which symptom reduction occurs.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this paper was supported in part by funds from the National Institute of Mental Health (Grant # R21 MH069425). We wish to acknowledge the significant contributions of consultants, Dr. Cameron Camp and Ms. Adel Herge, MS, OTR/L, the interventionists, Tracey Vause-Earland, MS, OTR/L, Michele Rifkin, MS, OTR/L, Catherine Piersol, MS, OTR/L, and Lauren Young Lapin, MS, OTR/L, and the interviewing staff. Clinical Trials ID# NCT00259467.

APPENDIX A

Sample Activity Prescription

Today’s Date:

| Your Husband’s Abilities: |

|

| Recommended Activity: Wood Craft |

| Activity Goal: Your husband will paint/stain wood boxes with familiar paintbrush for 30 minutes, one time per week. |

Simplify the setting for the activity

Set up the area to enhance your husband’s orientation and success in completing the activity.

Remove all objects from dining room table except a protective covering and Craft objects.

Place one wood box on the table in your husband’s field of vision (within 24 inches).

Make sure overhead light is on.

Simplify the Activity

Allow sufficient time to complete the “task of the day”. Stacey may only Paint/stain wood box for 10–15 minutes. That’s okay. He may return to the task after a short break.

Provide your husband with one box at a time.

Relax standard of performance (there is no right or wrong way).

Enhance Participation

Draw on your husband’s ability to engage in repetitive activities.

Draw on your husband’s ability to work well with his hands and painting history.

Your husband has great “activity tolerance” and sticks with a meaningful activity until his is tired. Monitor level of frustration.

You may need to help your husband initiate and sequence the activity. Use a guiding touch and a simple command to redirect if needed.

Choose time of day when your husband is at his best – Alert and energized.

Communicate Effectively

As you do naturally, continue to use encouraging remarks as he participates in the activity.

Use short, clear and precise instructions

If Stacey looses focus, use a calm voice and touch to guide him back to the task. Again, use praise and encouragement to continue.

Strategies for You

Try to relax; take a few deep breaths

Remember, there is no right or wrong way to do the activity

Feel good about yourself – you are doing a great job

References

- 1. [Accessed April 11, 2007];Alzheimer’s Association: Alzheimer’s Association Facts and Figures 2007. 2007 Alzheimer’s Association Web site, Available at http://www.alz.org/national/documents/Report_2007FactsAndFigures.pdf.

- 2.Finkel SI, Burns A, editors. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD): A clinical and research update. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12(S1) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyketsos CG, Sheppard JME, Steinberg M, et al. Neuropsychiatric disturbance in Alzheimer’s disease clusters into three groups: The Cache County study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:1043–1053. doi: 10.1002/gps.448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landes AM, Sperry SD, Strauss ME. Prevalence of Apathy, Dysphoria, and Depression in relation to dementia severity in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17:342–349. doi: 10.1176/jnp.17.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ballard C, Lowery K, Powell I, et al. Impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia on caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:93–105. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fauth EB, Zarit SH, Femia EE, et al. Behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and caregivers’ stress appraisals: Intra-individual stability and change over short-term observations. Aging Ment Health. 2006;10:563–573. doi: 10.1080/13607860600638107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gilley DW, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, et al. Influence of behavioral symptoms on rates on institutionalization for person’s with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Med. 2004;34:1129–1135. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703001831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Magai C, Hartung R, Cohen CI. In: Caregiver distress and behavioral symptoms, in Behavioral complications in Alzheimer’s disease. Lawlor BA, editor. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.; 1995. pp. 223–243. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for Dementia. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294:1934–1943. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.15.1934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;35:1525–1538. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sink KM, Holden KF, Yaffee K. Pharmacological treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms of Dementia: A review of evidence. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;293:596–608. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.5.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gitlin LN, Corcoran MA, Winter L, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of a home environmental intervention: Effect on efficacy and upset in caregivers and on daily function of persons with dementia. Gerontologist. 2001;41:15–30. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gitlin LN, Winter L, Corcoran MA, et al. Effects of the Home Environmental Skill-Building Program on the Caregiver–Care Recipient Dyad: 6-Month Outcomes From. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belle SH, Burgio L, Burns R, et al. Enhancing the Quality of Life of Dementia Caregivers from Different Ethnic or Racial Groups: A Randomized, Controlled Trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:727–738. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mittelman MS. Nonpharmacologic management and treatment: Effect of support and counseling on caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2000;12:341–346. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lyketsos CG, Colenda CC, Beck C, et al. Position statement of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry regarding principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:561–573. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000221334.65330.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Covinsky KE, Johnson CB. Envisioning Better Approaches for Dementia Care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:780–781. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-10-200611210-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall MJ, Hutchinson SA. A critique of research on the use of activities with person with Alzheimer’s disease: A systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2001;35:488–496. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cohen-Mansfield J. Nonpharmacologic interventions for inappropriate behaviors in dementia: A review, summary, and critique. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;9:361–381. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. Progressively lowered stress threshold: A conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1987;1:399–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lawton MP, Nahemow LE. Ecology and the aging process, in The Psychology of Adult Development and Aging. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1973. pp. 619–674. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Teri L, Logsdon RG. Identifying pleasant activities for Alzheimer’s disease patients: the pleasant events schedule-AD. Gerontologist. 1991;31:124–127. doi: 10.1093/geront/31.1.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jurica PJ, Leittenn CL, Mattis S. Dementia Rating Scale-2: Professional Manual. Lutz, FL, Psychological Assessment Resources. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen CK, Blue T. In: Cognitive disabilities model: How to make clinical judgments, in Cognition Occupation in Rehabilitation: Cognitive models for intervention and occupational therapy. Katz N, editor. Bethesda, MD: The American Occupational Therapy Association; 1998. pp. 225–279. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blue T, Allen CK. Allen Diagnostic Module Sensory Motor Stimulation Kit II. Colchester, CT: S&S Worldwide; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Earhart CA, Pollard D, Allen CK, et al. Large Allen Cognitive Level Screen (LACLS) 2000 Test Manual. Colchester, CT: S&S Worldwide; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Logsdon RG, Teri L, Weiner MF, et al. Assessment of agitation in Alzheimer’s disease: The agitated behavior in dementia scale. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1354–1358. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07439.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Teri L, Truax P, Logsdon R, et al. Assessment of behavioral problems in dementia: The Revised Memory and Behavior Problems Checklist (RMBPC) Psychol Aging. 1992;7:622–631. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.7.4.622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alexopoulos GS, Abrams RC, Young RC, et al. Cornell Scale for Depression in dementia. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;23:271–284. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(88)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Logsdon RG, Gibbons Le, McCurry SM, et al. Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:510–519. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200205000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lawton MP, Kleban MH, Moss M, et al. Measuring caregiving appraisal. J Gerontol. 1989;3:61–71. doi: 10.1093/geronj/44.3.p61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bedard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit Burden Interview: A new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41:652–657. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.5.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mahoney DF, Jones RN, Coon D, et al. The Caregiver Vigilance Scale: Application and validation in the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver (REACH) project. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2003;18:39–48. doi: 10.1177/153331750301800110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Radloff LS. CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kolanowski AM, Buettner L, Costa PT, Jr, et al. Capturing interests: Therapeutic recreation activities for persons with dementia. Ther Recreation J. 2001;35:220–235. [Google Scholar]; 36 Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis M, et al. Strategies used by families to simplify tasks for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders: Psychometric analysis of the task management strategy index (TMSI) Gerontologist. 2002;42:61–69. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cohen-Mansfield J, Parpura-Gill A, Golander H, et al. Utilization of Self-Identity Roles for Designating Interventions for Persons with Dementia. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2006;4:202–212. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.4.p202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gallagher-Thompson D, Shurgot GR, Rider K, et al. Ethnicity, stress, and cortisol function in Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White Women: A preliminary study of family dementia caregivers and noncaregivers. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;14:334–342. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000206485.73618.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Richards KC, Beck CK. Progressively lowered stress threshold model: Understanding behavioral symptoms of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1774–1775. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boucher LA. Disruptive behaviors in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease: A behavioral approach. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 1999;14:351–356. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schulz R, Hebert RS, Dew MA, et al. Patient Suffering and Caregiver Compassion: New opportunities for Research, Practice, and Policy. Gerontologist. 2007;47:4–13. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kraemer HC, Mintz J, Noda A, et al. Caution regarding the use of pilot studies to guide power calculations for study proposals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:484–489. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]