Abstract

Objective

To determine the lifetime burden and risk factors for hospitalization after heart failure (HF) diagnosis in the community.

Background

Hospitalizations in patients with HF represent a major public health problem, however the cumulative burden of hospitalizations after HF diagnosis is unknown, and no consistent risk factors for hospitalization have been identified.

Methods

We validated a random sample of all incident HF cases in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1987–2006 and evaluated all hospitalizations after HF diagnosis through 2007. International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision codes were used to determine the primary reason for hospitalization. To account for repeated events, Andersen-Gill models were used to determine the predictors of hospitalization after HF diagnosis. Patients were censored at death or last follow-up.

Results

Among 1077 HF patients (mean age 76.8 years, 582 [54.0%] female), 4359 hospitalizations occurred over a mean follow-up of 4.7 years. Hospitalizations were common after HF diagnosis, with 895 (83.1%) patients hospitalized at least once, and 721 (66.9%), 577 (53.6%) and 459 (42.6%) hospitalized ≥2, ≥3, and ≥4 times, respectively. The reason for hospitalization was HF in 713 (16.5%) hospitalizations, other cardiovascular in 936 (21.6%), while over half (n=2679, 61.9%) were non-cardiovascular. Male sex, diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anemia, and creatinine clearance <30 mL/min were independent predictors of hospitalization (p<0.05 for each).

Conclusions

Multiple hospitalizations are common after HF diagnosis, though less than half are due to cardiovascular causes. Comorbid conditions are strongly associated with hospitalizations, information that could be used to define effective interventions to prevent hospitalizations in HF patients.

Keywords: heart failure, epidemiology, hospitalization, community, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

An estimated 5.3 million Americans are living with heart failure (HF) and its prevalence has risen(1). Though improvements in mortality after HF diagnosis have been noted(2,3), hospitalizations related to HF have increased, from an estimated 400,000 discharges in 1979 to nearly 1.1 million in 2005(1). With growing numbers of patients living with HF and increasing hospitalizations, HF costs are significant, with 2008 U.S. estimated costs of 34.8 billion dollars(1). Thus, HF constitutes a major public health problem, a large component of which is related to hospitalizations. Yet, little is known about the natural history of hospitalizations after diagnosis of HF. Further, data on the cause of hospitalization after HF diagnosis are sparse. Finally, it has been recently underscored that no consistent predictors of hospitalization in patients with HF have emerged, which hinders the development of effective interventions(4).

While important knowledge has been gained from patients enrolled in HF clinical trials and from databases comprised of patients hospitalized with HF, these studies cannot fully appraise the total burden of hospitalization in patients with HF. Indeed, patients enrolled in clinical trials differ from the community as they are younger, more frequently male, and have low ejection fraction (EF)(5). Further, large HF registries and databases focus only on patients who have already been hospitalized for decompensated HF(6–8) who may not represent the community, as hospitalization for HF has been shown to be a poor prognostic sign(9,10), and these patients may be at higher risk for subsequent HF hospitalizations(11). Finally, the use of prevalent cases and analysis of only short-term rehospitalization prevents examination of the cumulative lifetime burden of hospitalizations in patients following initial HF diagnosis.

To address these gaps in knowledge, we undertook the present study of incident HF cases diagnosed from 1987–2006 in a stable community setting to examine the frequency and causes of all hospitalizations that occurred over the course of a lifetime after HF diagnosis, and whether changes have occurred over time. Second, we determined the risk factors for hospitalization after HF diagnosis.

METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This study was conducted in Olmsted County, Minnesota, which has an estimated 2006 population of 137,521, 90% of whom are Caucasian. Population-based research is possible because there are few healthcare providers; the largest is Mayo Clinic. Medical records from all sources of care for residents are extensively indexed and linked via the Rochester Epidemiology Project(12). Herein, all patient-level information was obtained via the medical and administrative records. Patients were excluded from analysis if they declined to provide Minnesota Research Authorization. Studies were approved by the Mayo Clinic and Olmsted Medical Center Institutional Review Boards.

Patient Identification

Olmsted County residents with a possible HF diagnosis were identified using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) code 428 (HF). Codes are assigned based on physician diagnoses during outpatient visits or at hospital discharge. From all patients with ICD-9 code 428, a subset was randomly selected to undergo case validation and data abstraction. The HF index date was defined as the first evidence of HF in the medical record. Patients diagnosed with HF prior to the study period were excluded. Cases were validated using methods previously described(2). Abstractors reviewed records to ensure the HF episode met Framingham criteria. When utilized previously, missing data were minimal and Framingham criteria could be applied in 98% of cases. The inter-abstractor agreement was 100%, indicating these methods are highly reproducible.

Patient-Level Data

Baseline characteristics were abstracted from the medical record. Physician’s diagnosis was used to define hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease. Smoking status was classified as ‘current’ or ‘prior/never’. Hypertension was defined by physician diagnosis, systolic blood pressure >140mm Hg, or diastolic blood pressure >90mm Hg. Diabetes mellitus was defined by blood glucose levels or use of diabetic medications. Prior myocardial infarction was defined using validated criteria(13). Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using weight and height at HF diagnosis. The Charlson Index, a comorbidity score, was calculated(14).

Hemoglobin, creatinine, and ejection fraction (EF) at HF diagnosis (within one year) were abstracted. Anemia was defined as hemoglobin<13mg/dL in men or <12mg/dL in women(15). Creatinine clearance was estimated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation(16).

Study Outcomes

Data on all-cause hospitalizations occurring after HF diagnosis from 1987–2007 were obtained through the Olmsted County Healthcare Expenditure and Utilization Database, which contains information regarding Olmsted County hospitalizations since 1987(15). For patients hospitalized at initial HF diagnosis, only subsequent hospitalizations were analyzed. In-hospital transfers or between the Olmsted Medical Center and Mayo Clinic hospitals were considered a single hospitalization. Hospital admissions within one day of the previous discharge were reviewed to determine whether they represented separate hospitalizations.

The principal diagnosis for each hospitalization was assessed using the primary ICD-9 code. This code, assigned by trained personnel after discharge, reflects the main reason for admission. Subsequent ICD-9 codes were not examined as there is discretion in their number and order. The primary reason for hospitalization was divided into one of three categories(17,18): HF (ICD-9 codes Appendix A), other cardiovascular (ICD-9 390–459 except those used to define HF), or non-cardiovascular (all other ICD-9 codes). Non-cardiovascular codes were further grouped by type of problem.

Mortality follow-up occurred via the medical record. In addition to deaths noted in clinical care, the Mayo Clinic registration office records obituaries and local death notices, and death data are obtained from the State of Minnesota Department of Vital and Health Statistics quarterly.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline patient characteristics are presented as percentages or means (standard deviation [SD]). Differences in baseline characteristics by sex were tested using χ2 for categorical variables or a two sample t-test for continuous variables. The rate of hospitalization was examined by year of HF diagnosis (1987–91, 1992–96, 1997–2001, 2002–06) or by sex and was determined using the total hospitalizations divided by the person-years at risk for hospitalization. Differences were tested using Poisson regression. Trends in the length of stay according to year and differences by sex were analyzed using generalized linear models; length of stay was log transformed in analysis. The reason for hospitalization was examined overall, by year of HF diagnosis, and by sex. Trends in the reason for hospitalization by year of HF diagnosis were examined using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test; differences by sex were tested using the χ2 test. Andersen-Gill models(19) were used to identify the independent predictors of hospitalization. This technique allows all hospitalizations to be analyzed, in contrast to Cox modeling used in most studies which only consider the first hospitalization. Patients were censored at death or last follow-up. Missing data was <2% per variable with the exception of EF (n=281 missing). Multiple imputation was used to impute missing values. Five datasets were created and analyzed, with results combined using Rubin’s rules(20). Analyses were performed using SAS version 8.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and Splus version 8 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA). A p value of <0.05 was used as the level of significance.

RESULTS

Study Population

A total of 1091 patients with incident HF were identified from 1987–2006. Fourteen patients, hospitalized at initial HF diagnosis, died during that hospitalization and were excluded from analysis as they were ineligible for subsequent hospitalizations, resulting in a study population of 1077. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Compared to patients with reduced EF (<50%), patients with preserved EF (≥50%) were slightly older (77.8 vs 77.3 years for preserved versus reduced EF, respectively; p<0.001) and more likely female (58.6% vs 36.8% for preserved versus reduced EF, respectively; p<0.001). The proportion of patients with Charlson comorbidity index ≥3 increased over the study period (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| N missing | Overall (n=1077) | Men (n=495) | Women (n=582) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yrs) | - | 76.8 (12.7) | 73.3 (12.8) | 79.8 (11.8) | <0.001 |

| EF (%) | 281 | 46.3 (17.5) | 41.6 (15.9) | 50.6 (17.8) | <0.001 |

| Inpatient at HF Diagnosis | - | 56.0 | 55.6 | 56.3 | 0.82 |

| Year of HF Diagnosis | |||||

| 1987–91 | - | 20.8 | 21.0 | 20.6 | 0.70 |

| 1992–96 | - | 26.1 | 26.3 | 25.9 | -- |

| 1997–2001 | - | 26.5 | 27.7 | 25.4 | -- |

| 2002–06 | - | 26.6 | 25.1 | 28.0 | -- |

| Risk Factors and Comorbidities | |||||

| Hypertension | - | 74.6 | 65.9 | 82.0 | <0.001 |

| Current smoker | 12 | 14.2 | 19.1 | 10.1 | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | - | 44.3 | 49.1 | 40.2 | 0.003 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 | 21.1 | 23.7 | 18.9 | 0.06 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 17 | 29.4 (10.1) | 30.0 (10.2) | 28.8 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Prior MI | 4 | 20.1 | 24.9 | 16.0 | <0.001 |

| COPD | - | 23.5 | 26.9 | 20.6 | 0.02 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 1 | 24.6 | 24.0 | 25.1 | 0.68 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | - | 22.0 | 26.5 | 18.2 | 0.001 |

| Charlson index ≥3 | 5 | 43.0 | 46.1 | 40.3 | 0.06 |

| Laboratory Data | |||||

| Anemia | 15 | 43.9 | 45.0 | 42.9 | 0.50 |

| Creatinine clearance, mL/min | 10 | 58.2 (21.6) | 60.9 (22.8) | 56.0 (20.2) | <0.001 |

All values are percents or mean (standard deviation).

Hospitalizations After HF Diagnosis

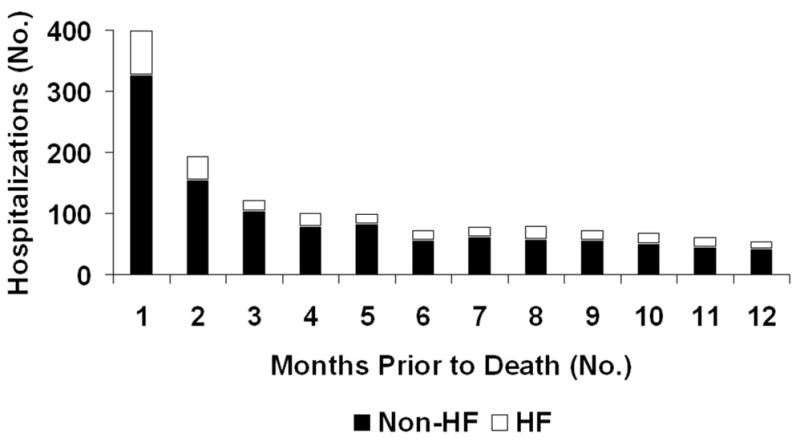

A total of 4359 hospitalizations occurred during a mean (SD) follow-up of 4.7 (3.9) years. At study end, 798 (74.1%) patients had died. Hospitalizations after HF diagnosis were common (Figure 1) and ranged from 0–42 (median 3) per person. A similar distribution was observed among those who died, where hospitalizations ranged from 0–42 (median 4) per person, indicative of lifetime hospitalizations after HF diagnosis. A total of 895 (83.1%) patients were hospitalized at least once, and 721 (66.9%), 577 (53.6%) and 459 (42.6%) were hospitalized ≥2, ≥3, and ≥4 times, respectively. Both HF and non-HF hospitalizations increased in the months prior to death (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Number of Hospitalizations Per Person After Heart Failure Diagnosis.

The number of hospitalizations per individual from heart failure diagnosis until death or last follow-up are shown.

Figure 2. Number of Hospitalizations In the Year Prior to Death.

The number of heart failure and non-heart failure hospitalizations in the year before death among patients who died during follow-up (n=798) are shown.

The mean rate of hospitalization was 86.6 per 100 person years (95% confidence interval [CI] 84.0–89.2). Thus, for each year after HF diagnosis, patients were hospitalized 0.87 times on average, or nearly once per year. Men were hospitalized more frequently with 92.0 hospitalizations per 100 person years (95% CI 88.2–95.9) compared with 81.8 hospitalizations per 100 person years (95% CI 78.4–85.3) for women (p<0.001). The rate of hospitalization after HF did not change over time.

The median (25th, 75th percentile) length of stay per hospitalization was 5 (3, 7) days. The length of stay declined over the study period, with median values of 6, 5, 5, 4 days for hospitalizations from 1987–91, 1992–96, 1997–2001, and 2002–07, respectively (p for trend <0.001). Length of stay was similar among men and women (median 5 vs. 5 days, p=0.40).

Primary Reason for Hospitalization

ICD-9 codes were missing in 31 of 4359 (<1%) hospitalizations, leaving 4328 included in the reason for hospitalization analysis (Table 2). HF was the primary reason for hospitalization in 713 (16.5%) hospitalizations, while 936 (21.6%) were due to other cardiovascular causes. Most hospitalizations (n=2679, 61.9%) were due to non-cardiovascular causes. The primary cause of hospitalization did not differ by sex (p=0.106), but changed over time (p<0.001), with a decrease in the proportion of hospitalizations due to HF noted. The most common reasons for other cardiovascular hospitalizations were ischemic heart disease (ICD-9 410–414, 299 of 936 hospitalizations, 31.9%), and arrhythmias (ICD-9 427, 249 of 936 hospitalizations, 26.6%).

Table 2.

Primary Cause of Hospitalization According to Year of Diagnosis and Sex

| Type of Hospitalization, N (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HF | Other CV | Non-CV | Total Hospitalizations | P value | |

| Overall | 713 (16.5) | 936 (21.6) | 2679 (61.9) | 4328 | |

| Year HF Diagnosis | <0.001 | ||||

| 1987–91 | 210 (19.4) | 200 (18.5) | 670 (62.0) | 1080 | |

| 1992–96 | 225 (16.8) | 299 (22.3) | 819 (61.0) | 1343 | |

| 1997–2001 | 184 (15.7) | 288 (24.6) | 699 (59.7) | 1171 | |

| 2002–06 | 94 (12.8) | 149 (20.3) | 491 (66.9) | 734 | |

| Sex | 0.11 | ||||

| Male | 359 (16.7) | 492 (22.9) | 1302 (60.5) | 2153 | |

| Female | 354 (16.3) | 444 (20.4) | 1377 (63.3) | 2175 | |

CV= cardiovascular

Reasons that accounted for >1% of non-cardiovascular hospitalizations are shown in Table 3. Respiratory tract infections, chronic lung disease, and other respiratory symptoms accounted for a large proportion of non-cardiovascular hospitalizations (30.4%). Bone and joint diseases accounted for an additional 11.0%. Comorbidities frequent in HF patients including kidney disease, psychiatric disease, and diabetes mellitus were additional common reasons for hospitalization.

Table 3.

Primary Cause of Non-Cardiovascular Hospitalizations Based on ICD-9 Codes

| Primary Cause* | ICD-9 Codes† | N | % of Total Hospitalizations (4328) | % of Non-CV Hospitalizations (2679) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | ||||

| Respiratory tract infections | 465–490, 507, 513, 011 | 398 | 9.2% | 14.9% |

| Chronic lung disease | 491–496, 511, 515, 516, 518, 519 | 254 | 5.9% | 9.5% |

| Respiratory symptoms, other | 786 | 162 | 3.7% | 6.0% |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||

| Bone disorders/fracture | 730–736, 802–824 | 188 | 4.3% | 7.0% |

| Joint disorders/osteoarthritis | 710–726 | 106 | 2.4% | 4.0% |

| Gastrointestinal | ||||

| Intestinal disorders | 555–569, 787, 789 | 184 | 4.3% | 6.9% |

| Esophagus/stomach/duodenum disorders | 530–537 | 61 | 1.4% | 2.3% |

| Liver, gallbladder, pancreas disorders | 571–577 | 52 | 1.2% | 1.9% |

| Gastrointestinal bleed | 578 | 49 | 1.1% | 1.8% |

| Kidney/ureter/bladder disorder including acute renal failure | 580–599, 788 | 143 | 3.3% | 5.3% |

| Cancer/benign tumors | 143–238 | 111 | 2.6% | 4.1% |

| Procedural/other medical complications | 996–999 | 101 | 2.3% | 3.8% |

| General symptoms | 780, 799 | 97 | 2.2% | 3.6% |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 276 | 73 | 1.7% | 2.7% |

| Non-respiratory infections | ||||

| Cellulitis/skin infections | 681–686 | 70 | 1.6% | 2.6% |

| Sepsis/other infection | 003, 008, 035–053, 078, 079, 112 | 69 | 1.6% | 2.6% |

| Diabetes mellitus | 250 | 69 | 1.6% | 2.6% |

| Psychiatric disease | 290–312 | 67 | 1.5% | 2.5% |

| Dermatologic disorders and skin ulcers | 692–707, 782 | 58 | 1.3% | 2.2% |

| Hernias | 550–553 | 44 | 1.0% | 1.6% |

Non-cardiovascular causes of hospitalization constituting ≥1% of the total hospitalizations are shown

ICD-9 codes were categorized according to first 3 digits (i.e. 465.XX) and grouped by problem type for purposes of reporting

CV= cardiovascular

Heart Failure Hospitalizations

While only 713 (16.5%) hospitalizations were due to HF, these were clustered among a fraction of the cohort, with just 348 of 1077 (32.3%) patients ever having a HF hospitalization after diagnosis (hospitalization at the time of incident HF diagnosis excluded). Overall, 39.8% of patients with EF<50% were hospitalized for HF at least once compared with 34.0% of patients with EF≥50% (p=0.069). Among the 348 with a HF hospitalization, the number of HF hospitalizations ranged from 1–21, and 205 (58.9%) had one, 67 (19.3%) had two, and 76 (21.8%) had 3 or more. The incident HF patients with 2 or more HF hospitalizations (n=143) accounted for the majority of HF hospitalizations (508 of 713, 71.2%). They were younger than the rest of the cohort (mean age 74.0 v. 77.2 years, p<0.001), had higher BMI (mean 31.1 v. 29.1 kg/m2, p=0.004), more frequently had diabetes (29.4% v. 19.8%, p=0.009), and less frequently had COPD (16.8% v. 24.5%, p=0.04). Other baseline characteristics were similar.

The length of stay for HF hospitalizations was similar to non-HF hospitalizations [median (25th, 75th percentile) 4 (3,7) vs. 5 (3, 8) days, respectively; p=0.064], and decreased over time with median values of 7, 5, 4, 4 days for hospitalizations from 1987–91, 1992–96, 1997–2001, and 2002–07, respectively (p for trend <0.001).

Risk Factors for Hospitalization After HF Diagnosis

The univariate predictors of hospitalization are shown in Figure 3. Age, hypertension, diabetes, COPD, peripheral vascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, anemia, and decreased renal function were each univariately associated with an increased risk of hospitalization. In multivariable analysis, male sex, diabetes, COPD, anemia, and a creatinine clearance <30 mL/min were independent predictors of hospitalization (Figure 4). Ancillary analysis examining “time to first” hospitalization after HF diagnosis using standard Cox modeling yielded similar results. In contrast to all-cause hospitalization, the independent predictors of a first HF hospitalization after diagnosis included diabetes (HR 1.56, 95% CI 1.20–2.02) and creatinine clearance 30 to <60 mL/min (HR 1.42, 95% CI 1.13–1.78). COPD was associated with a non-significant increase in risk of HF hospitalization (HR 1.29, 95% CI 0.99–1.68).

Figure 3. Univariate Predictors of Hospitalization After Heart Failure Diagnosis.

The unadjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for risk of hospitalization using Andersen-Gill modeling are shown.

Figure 4. Multivariable Predictors of Hospitalization After Heart Failure Diagnosis.

The adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) for risk of hospitalization using Andersen-Gill modeling are shown. All variables shown were included in the model.

DISCUSSION

In this community HF cohort, patients were hospitalized frequently after incident HF diagnosis over the course of their lifetime. The majority of hospitalizations were due to non-cardiovascular causes, the most common being respiratory etiologies. While HF was the primary reason for only 16.5% of hospitalizations, these were experienced by a small number of patients who often had repeated HF admissions. The independent risk factors for all-cause hospitalization were male sex, COPD, diabetes, anemia, and renal dysfunction.

Community Burden of Hospitalizations Among Incident HF Patients

The number of HF hospitalizations has increased dramatically over the past several decades(1,21,22). Data from the National Hospital Discharge Survey suggests that hospitalizations with any mention of HF have tripled from 1.3 million in 1979 to 3.9 million in 2004(21), and HF hospitalizations have become a major public health burden. Community studies indicate that while the incidence of HF has remained stable over time, survival has improved, leading to an increase in the prevalence of HF in the U.S.(2,3), which suggests that the increase in HF hospitalizations reflects, in part, the larger population of patients. Yet, little is known about the burden of hospitalization among HF patients, including the rate and cumulative number of hospitalizations per patient that occur after HF diagnosis and whether temporal changes have occurred. Studies have suggested that readmission rates are high in patients with a prior HF admission(8,23,24); however, these data may lack generalizability as they are limited to patients with a HF hospitalization, itself a poor prognostic sign(9,10).

The present study brings important new knowledge by examining hospitalizations over the course of a lifetime after incident HF diagnosis, thereby enabling us to report on the comprehensive experience of patients living with HF in the community. Our findings indicate that hospitalizations are common after HF diagnosis, occurring nearly once per year. The majority (83%) of HF patients experienced at least one hospitalization after diagnosis, and multiple hospitalizations were common. Further, the rate of admissions for individuals diagnosed with HF showed no signs of abatement in recent years. These findings are particularly striking given the extensive efforts to reduce hospitalizations in HF(25), and raise the question of the cause of HF hospitalizations.

Primary Reason for Hospitalization

Little is known about the etiology of hospitalizations among HF patients. Fang et al examined hospitalizations from the National Hospital Discharge Survey from 1979–2004(21). They found the proportion of hospitalizations with HF as a first-listed diagnosis remained at approximately 30% over the study period. However, there was a decline in the proportion of admissions due to coronary or other cardiovascular diseases, and an increase in the proportion due to non-cardiovascular diseases. Curtis et al examined hospital readmission rates among Medicare beneficiaries hospitalized with HF from 2001–05(8), and found that approximately 27% of readmissions were due to HF. This analysis did not include patients without a prior HF hospitalization and only examined the first readmission, thus cannot provide information on the total burden of hospitalizations. To date, the cause of hospitalization among community HF patients, and potential temporal changes, remain unclear.

The present analysis indicates that HF is the primary cause of hospitalization only 16.5% of the time. However, among patients with at least one HF hospitalization, repeat HF admissions are common, and a small proportion of HF patients account for the majority of HF admissions. Importantly, most hospitalizations were due to non-cardiovascular causes (62%), and HF hospitalizations have decreased over time. There are several potential explanations for these findings. First, the prevalence of HF patients with preserved EF may have increased(26), and these patients often have more comorbidities that could lead to non-HF hospitalizations. While patients with reduced EF experienced HF admissions more commonly than preserved EF patients (40% v. 34%, respectively), the difference was not significant. Second, the shift to non-HF causes of hospitalizations may be attributable to the observed increase in the burden of comorbidities among HF patients over time. Further, changes in diagnosis or coding patterns resulting in a shift from HF to other causes could not be excluded. The implications of these findings are two-fold: first, community HF patients are elderly and have a high burden of comorbidities which may necessitate hospitalization even if HF is well-treated, and second, addressing non-HF comorbidities may prevent hospitalizations in HF patients.

Risk Factors for Hospitalization After HF Diagnosis

Recent public health efforts have aimed to decrease hospitalizations in HF. Certainly, HF admission has emerged as a risk factor for hospital readmission(8). However, despite multiple studies, no consistent predictors of readmission among patients with HF have emerged(4). Though there are several studies evaluating models of readmission predictors following a HF admission(8,11,27,28), they have limited risk prediction to patients with a prior HF admission, have had short follow-up periods, and have restricted analyses to “time-to-first” hospitalization, thereby missing the cumulative burden of hospitalizations that may occur over the course of a lifetime after HF diagnosis. To the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined predictors of admission using incident validated HF patients followed for a prolonged time period, or used modeling techniques to account for repeated hospitalizations after HF diagnosis. As HF is a chronic disease characterized by periodic exacerbations often leading to multiple hospitalizations, analyzing only the first rehospitalization excludes information from subsequent hospitalizations. Herein, independent risk factors for all-cause admissions after HF diagnosis are male sex, diabetes mellitus, COPD, anemia, and reduced creatinine clearance at HF diagnosis. Detection of these factors among newly diagnosed HF patients may help in identifying those at highest risk for multiple admissions, and for whom more intense care is needed. The fact that most hospitalizations among HF patients are due to non-HF causes underscores the urgent need to determine whether targeting comorbidities could lead to a decrease in hospitalizations.

Study Limitations

Some limitations should be acknowledged to aid in data interpretation. First, while all hospitalizations in the community were captured in our study, hospitalizations outside of the county were not included. However, as the county is relatively isolated, hospitalizations outside of the county are likely rare. Second, the use of ICD-9 codes to identify the cause of hospitalization may lead to some misclassification. However, ICD-9 codes for HF have not changed over the study period, and methods for determining primary ICD-9 codes at Mayo Clinic have remained constant, and thus should not bias examination of secular trends. Whether the burden of hospitalizations observed in HF patients differs from the general elderly population was not examined, though patients admitted with HF have been demonstrated to have higher readmission rates than other diagnoses in the Medicare population (29). We cannot exclude that unmeasured characteristics such as medication adherence and clinical care, which were not evaluated, may impact hospitalizations. Further, an assumption of the Andersen-Gill model is that all hospitalizations have a common baseline hazard function. There is no clinical indication that this assumption does not hold. Lastly, while Olmsted County is becoming increasingly diverse, the population remains largely Caucasian, and hospitalizations after HF diagnosis may differ in other racial and ethnic groups. However, our study has several important strengths, including the use of a validated, incident, community HF population followed for a prolonged period of time with the ability to capture all subsequent hospitalizations, thereby allowing us to assess the burden and risk factors for hospitalization after HF diagnosis.

Clinical Implications and Conclusions

As the costs of medical care in the U.S. continue to rise, decreasing hospitalizations among patients with HF is critically important. Our findings indicate that hospitalizations are common, occurring nearly once per year after diagnosis. However, the majority are due to non-cardiovascular causes, with HF hospitalizations experienced by only a third of all HF patients. The relationship between comorbidities and increased hospitalization risk, coupled with a shift towards non-HF related causes, indicate that comorbidities play a central and increasing role in hospitalizations in patients with HF. These data have important implications for preventive efforts to reduce the burden of hospitalization among patients with HF. Indeed, to be effective, strategies aiming to reduce hospitalization must include the identification and management of comorbid conditions in addition to addressing HF manifestations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources and Disclosures: This study was funded by a National Institute of Health RO1 Grant (HL72435) for Dr. Roger, an American Heart Association Postdoctoral Fellowship Award for Dr. Dunlay, and a National Institute of Health Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award (T32 HL07111-31A1) for Dr. Dunlay, and was made possible by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant #R01-AR30582 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases). The authors have no disclosures.

We would like to thank Ruoxiang Jiang for her assistance with the statistical analysis.

ABBREVIATIONS

- BMI

body mass index

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- EF

ejection fraction

- HF

heart failure

- ICD-9

International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Association AH, editor. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics 2008 Update. 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roger VL, Weston SA, Redfield MM, et al. Trends in heart failure incidence and survival in a community-based population. Jama. 2004;292:344–50. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.3.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy D, Kenchaiah S, Larson MG, et al. Long-term trends in the incidence of and survival with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1397–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ross JS, Mulvey GK, Stauffer B, et al. Statistical models and patient predictors of readmission for heart failure: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:1371–86. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lloyd-Williams F, Mair F, Shiels C, et al. Why are patients in clinical trials of heart failure not like those we see in everyday practice? J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:1157–62. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abraham WT, Fonarow GC, Albert NM, et al. Predictors of in-hospital mortality in patients hospitalized for heart failure: insights from the Organized Program to Initiate Lifesaving Treatment in Hospitalized Patients with Heart Failure (OPTIMIZE-HF) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:347–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonarow GC. The Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE): opportunities to improve care of patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2003;4 (Suppl 7):S21–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curtis LH, Greiner MA, Hammill BG, et al. Early and long-term outcomes of heart failure in elderly persons, 2001–2005. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:2481–8. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.22.2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Setoguchi S, Stevenson LW, Schneeweiss S. Repeated hospitalizations predict mortality in the community population with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154:260–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Solomon SD, Dobson J, Pocock S, et al. Influence of nonfatal hospitalization for heart failure on subsequent mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:1482–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felker GM, Leimberger JD, Califf RM, et al. Risk stratification after hospitalization for decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004;10:460–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melton LJ., 3rd History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–74. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roger VL, Killian J, Henkel M, et al. Coronary disease surveillance in Olmsted County objectives and methodology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55:593–601. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(02)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–83. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Nutritional Anemias: Report of a WHO Scientific Group. WHO Technical Report Series. 1968;405:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:461–70. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerber Y, Jacobsen SJ, Frye RL, Weston SA, Killian JM, Roger VL. Secular trends in deaths from cardiovascular diseases: a 25-year community study. Circulation. 2006;113:2285–92. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.590463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hauptman PJ, Swindle J, Burroughs TE, Schnitzler MA. Resource utilization in patients hospitalized with heart failure: insights from a contemporary national hospital database. Am Heart J. 2008;155:978–985. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen PK, Gill RD. Cox’s regression model for counting processes: a large sample study. Ann Stat. 1982;10:1100–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rubin D. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: J Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fang J, Mensah GA, Croft JB, Keenan NL. Heart failure-related hospitalization in the U.S. 1979 to 2004. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:428–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haldeman GA, Croft JB, Giles WH, Rashidee A. Hospitalization of patients with heart failure: National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1985 to 1995. Am Heart J. 1999;137:352–60. doi: 10.1053/hj.1999.v137.95495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Howie-Esquivel J, Dracup K. Effect of gender, ethnicity, pulmonary disease, and symptom stability on rehospitalization in patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:1139–44. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.04.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krumholz HM, Parent EM, Tu N, et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah MR, Whellan DJ, Peterson ED, et al. Delivering heart failure disease management in 3 tertiary care centers: key clinical components and venues of care. Am Heart J. 2008;155:764, e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Owan TE, Hodge DO, Herges RM, Jacobsen SJ, Roger VL, Redfield MM. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:251–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa052256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krumholz HM, Chen YT, Wang Y, Vaccarino V, Radford MJ, Horwitz RI. Predictors of readmission among elderly survivors of admission with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2000;139:72–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(00)90311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamokoski LM, Hasselblad V, Moser DK, et al. Prediction of rehospitalization and death in severe heart failure by physicians and nurses of the ESCAPE trial. J Card Fail. 2007;13:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1418–28. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.