Abstract

Overexpression of nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov), a member of the Cyr 61, connective tissue growth factor, Nov family of proteins, inhibits osteoblastogenesis and causes osteopenia. The consequences of Nov inactivation on osteoblastogenesis and the postnatal skeleton are not known. To study the function of Nov, we inactivated Nov by homologous recombination. Nov null mice were maintained in a C57BL/6 genetic background after the removal of the neomycin selection cassette and compared with wild-type controls of identical genetic composition. Nov null mice were identified by genotyping and absent Nov mRNA in calvarial extracts and osteoblast cultures. Nov null mice did not exhibit developmental skeletal abnormalities or postnatal changes in weight, femoral length, body fat, or bone mineral density and appeared normal. Bone volume and trabecular number were decreased only in 1-month-old female mice. In older mice, after 7 months of age, osteoblast surface and bone formation were increased in females, and osteoclast and eroded surfaces were increased in male Nov null mice. Calvarial osteoblasts from Nov null mice displayed enhanced alkaline phosphatase activity, alkaline phosphatase mRNA, and transactivation of a bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)/phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic reporter construct in response to BMP-2. Similar results were obtained after the down-regulation of Nov by RNA interference in ST-2 stromal and MC3T3 cells. Osteoclast number was increased in marrow stromal cell cultures from Nov null mice. Surface plasmon resonance demonstrated direct interactions between Nov and BMP-2. In conclusion, Nov sensitizes osteoblasts to BMP-2, but Nov is dispensable for the maintenance of bone mass.

Nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov) interacts directly with bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2) and its inactivation sensitizes cells of the osteoblastic lineage to BMP-2 and causes modest phenotypic skeletal changes in vivo.

Members of the Cyr 61, connective tissue growth factor, Nov (CCN) family of cysteine-rich secreted proteins include cysteine-rich 61 (Cyr 61), connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov), and Wnt-inducible secreted proteins (WISP)-1, -2, and -3 (1,2). CCN proteins are highly conserved and share four distinct modules: an IGF-binding domain, a von Willebrand type C domain, containing the cysteine-rich domain, a thrombospondin-1 domain, and a C-terminal domain, important for protein-protein interactions (1,2). CCN proteins are structurally related to certain bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) antagonists, such as twisted gastrulation and chordin, and can have important interactions with regulators of osteoblast cell growth and differentiation (3). Some CCN proteins, such as CTGF and Nov, bind to BMPs, resembling the actions of more classic BMP antagonists, and their overexpression in vivo causes osteopenia (4,5,6).

Nov was identified as an aberrantly expressed gene in avian nephroblastoma induced by myeloblastosis-associated virus (7). It shares 50% sequence homology with Cyr 61 and CTGF and is expressed in a variety of tissues, including bone and cartilage (8,9). Nov acts as a ligand of integrin receptors, and as a consequence it mediates fibroblast and endothelial cell adhesion and chemotaxis (10,11). Nov interacts with the extracellular domain of Notch, leading to the activation of this transmembrane receptor and the inhibition of myoblast differentiation (12). Nov also colocalizes and interacts with connexin 43, a factor important in cell-cell communication, skeletal development, and osteoblast function (13,14,15). Nov has angiogenic properties and enhances TGF-β2 signaling and activity in chondrocytes but not osteoblasts (5,9,16). Recently we examined the effect of Nov overexpression on skeletal cells in vivo and in vitro. Transgenics overexpressing Nov under the control of the osteocalcin promoter exhibit decreased bone formation leading to osteopenia (5). Overexpression of Nov in stromal cells decreases the effect of BMP-2 on osteoblastogenesis, and impairs BMP/phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic (Smad) signaling. These observations demonstrate that Nov is a previously undiscovered BMP antagonist. However, the consequences of Nov inactivation on skeletal homeostasis have not been defined. A skeletal developmental phenotype of mice expressing a truncated Nov protein was recently reported, but the adult skeletal phenotype was not examined (17). Furthermore, the truncated protein as well as the presence of a neomycin selection cassette could have caused or modified the phenotypic characteristics described (18,19).

The intent of the present study was to define the function of Nov in skeletal tissue in vivo. For this purpose, we created Nov null mice, in which the entire coding sequence of Nov was deleted. After the removal of the neomycin selection cassette, we determined the developmental and general characteristics, body composition, and adult skeletal phenotype of Nov null mice. We also examined mechanisms of Nov action in Nov null osteoblasts and osteoblastic cell lines after the down-regulation of Nov by RNA interference (RNAi).

Materials and Methods

Generation of Nov null mice

Nov null mice were created by homologous recombination, resulting in the replacement of the coding region of Nov with a LacZ/neomycin (LacZ/Neo) cassette. Targeted embryonic stem (ES) cells harboring a null allele for Nov were generated using Velocigene technology at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (20). Briefly, a bacterial artificial chromosome-containing mouse genomic DNA encompassing Nov sequences was selected by PCR screen from a 129/SvJ mouse bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library containing about 175 kb of genomic DNA (Incyte Genomics BAC ID 427a3, Wilmington, DE) (21). To generate the targeting vector, the entire coding sequence of Nov from ATG to STOP was replaced with a LacZ/Neo cassette in frame using bacterial homologous recombination (Fig. 1) (22,23,24). The neo selection minigene was flanked by loxP sequences to allow its excision by Cre recombination (25).

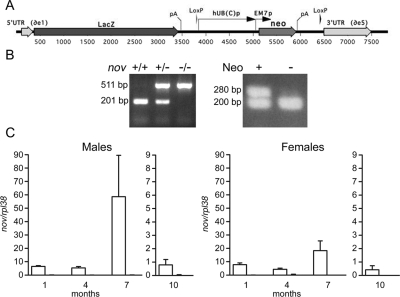

Figure 1.

A, Schematic representation of the Nov locus and engineering of a Nov null allele. A LacZ/Neo phosphotransferase cassette replaced the coding sequence of Nov from the initiating Met codon in exon 1 to the STOP codon in exon 5. LacZ is followed by Simian virus 40 polyadenylation signal and associated sequences, and the neomycin cassette is followed by the mouse phosphoglycerate kinase polyadenylation signal and associated sequences. The neomycin cassette is flanked by loxP sequences. B, A representative PCR analysis of calvarial DNA from Nov null and control wild-type mice before (left panel) and after (right panel) the removal of the neomycin cassette. On the left, the 511-bp band is detected in Nov null mice and a 201-bp band detected in wild-type controls. On the right, a 280-bp band is detected before but not after the removal of the neo cassette. A 200-bp band represents an internal PCR control from the T cell receptor δ chain gene. C, Real time RT-PCR of RNA extracts from 1-, 4-, 7-, and 10-month-old calvarial extracts from Nov null mice (undetectable) and wild-type littermate controls (white bars). Data are expressed as Nov copy number corrected for rpl38. Values are means ± sem; n = 4.

Using restriction mapping, it was determined that the modified BAC had homology arms of approximately 145 and 30 kb flanking the LacZ/Neo cassette, and it was used as a vector to target Nov in a C57BL/6–129SvJ hybrid ES line. ES cell clones were genotyped using a loss of allele assay, and 10 of 288 clones screened were targeted, indicating a targeting frequency of 3.5%. Targeted ES cell lines were used to generate chimeric male mice at the transgenic facility of the University of Connecticut Health Center. Chimeras that were complete transmitters of ES-derived sperm were bred to C57BL/6 females to generate F1 heterozygous mice, which were genotyped by loss of allele assays. F1 mice were crossed with C57BL/6 mice to create heterozygous mice in a mixed 129SvJ/C57BL/6 genetic background.

To excise the neo cassette, Nov null mice were crossed with homogeneous C57BL/6 mice expressing the Cre recombinase under the control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter. The resulting Cre recombinase transgene was segregated by mating with C57BL/6 wild-type mice. The heterozygous mice carrying the deleted Nov gene, in the absence of the neo cassette and the Cre recombinase, were intercrossed to obtain homozygous null mice, which were backcrossed seven times into a uniform C57BL/6 genetic background.

Nov null mice were genotyped by PCR using primers 5′-GGTCAATCCGCCGTTTGTTCC-3′ and 5′-TAGTCACGCAACTCGCCGCACATC-3′ flanking LacZ to amplify a 511-bp fragment in the Nov null allele. The wild-type allele was identified by primers 5′-CCCCCACAACACCAAAACC-3′ and 5′-TGCCTCAACCAATATGCTTCC-3′ used to amplify at 201-bp fragment. Deletion of the neo cassette by Cre recombination was determined by PCR using a 5′-CTTGGGTGGAGAGGCTATTC-3′ and a 5′-AGGTGAGATGACAGGAGATC-3′ primer flanking sequences within the neo cassette and amplifying a 280-bp fragment and an internal control using a 5′-CAAATGTTGCTTGTCTGGTG-3′ and a 5′-GTCAGTCGAGTGCACAGTTT-3′ primer to amplify a 200-bp fragment from the Nov locus. The Nov null state was confirmed by documenting absence of Nov mRNA in calvarial extracts by real-time RT-PCR (26,27). Nov null (Nov−/−) mice were compared with wild-type littermate controls (Nov+/+) after the intermating of Nov heterozygous mice. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Saint Francis Hospital and Medical Center.

Skeletal staining

To assess the effect of Nov on skeletal development, skeletons from embryos 15 and 18 d after coitum and from newborns were fixed with ethanol. Cartilage was stained with Alcian blue and mineralized bone with alizarin red, followed by the addition of 1% potassium hydroxide to remove adjacent tissues, as described (28).

X-ray analysis, bone mineral density (BMD), body composition, and femoral length

X-rays were performed on eviscerated mice at an intensity of 30 kW for 20 sec on a Faxitron x-ray system (model MX 20; Faxitron X-Ray Corp., Wheeling, IL). Total BMD (grams per square centimeter) and total body fat (grams) were measured on anesthetized mice using the PIXImus small animal DEXA system (GE Medical System/Lunar, Madison, WI) (29). Femoral images were used to determine femoral length in mm. Calibrations were performed with a phantom of defined value, and quality assurance measurements were performed before each use. The coefficient of variation for total BMD is less than 1% (n = 9).

Bone histomorphometric analysis

Static and dynamic histomorphometry was carried out on Nov null and control mice after they were injected with calcein, 20 mg/kg, and demeclocycline, 50 mg/kg, at an interval of 2 d for 1-month-old animals and 7 d for 4-, 7- and 10-month-old animals. They were killed by CO2 inhalation 2 d after the demeclocycline injection. Longitudinal sections, 5 μm thick, were cut on a microtome (Microm; Richards-Allan Scientific, Kalamazoo, MI) and stained with 0.1% toluidine blue or von Kossa. Static parameters of bone formation and resorption were measured in a defined area between 181 and 1080 μm from the growth plate, using an OsteoMeasure morphometry system (Osteometrics, Atlanta, GA) (30). For dynamic histomorphometry, mineralizing surface per bone surface and mineral apposition rate were measured on unstained sections under UV light, using a triple diamidino-2-phenylindole, fluorescein isothiocyanate, Texas red set long-pass filter, and bone formation rate was calculated. The terminology and units used are those recommended by the Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (31).

Microcomputed tomography (μCT)

Bone microarchitecture of femurs from Nov null and littermate control mice was analyzed by μCT (MicroCT40; Scanco Medical AG, Bassersdorf, Switzerland). The metaphyseal region of the distal femur was scanned for microarchitecture and cortical thickness was obtained at the midshaft. The femurs were scanned at low resolution, energy level of 45 keV, and intensity of 177 μA. The distal trabecular scan started about 0.6 mm proximal to the growth plate and extended proximally 1.5 mm. One hundred fifty cross-sectional slices were obtained at 12-μm intervals at the distal end, beginning at the edge of the growth plate and extending in a proximal direction, and 100 contiguous slices were selected for analysis. The voxel size used for analysis was 12 μm. Trabecular regions were assessed for bone volume fraction (bone volume/total volume), trabecular thickness, trabecular number, trabecular separation, connectivity density, and structure model index. The midshaft cortical thickness values were obtained by 18 slices at the midpoint of the femur.

Serum C-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type I collagen (CTX)

The serum bone remodeling marker CTX was measured by ELISA using RatLaps ELISA kits (Nordic Bioscience Diagnostics, Herlev, Denmark), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Primary osteoblast cell cultures

Osteoblasts were obtained from parietal bones of 3- to 5-d-old Nov null mice and wild-type control mice from both sexes. Osteoblasts were isolated by sequential collagenase digestions, as previously described (32). Osteoblasts were cultured in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented with nonessential amino acids, 20 mm HEPES, 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA) at 37 C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Subconfluent cells were trypsinized and these first passage cells were used for subsequent experiments. To test for changes in gene expression, cells were cultured for up to 14 d after confluence, in the presence of 100 μg/ml ascorbic acid and 5 mm β-glycerophosphate (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). To test for immediate effects of BMP-2, cells were cultured to confluence, serum deprived overnight, and treated with recombinant BMP-2 (Wyeth Research, Collegeville, PA) for 24 h and analyzed for changes in gene expression or treated for 72 h in the presence of serum and analyzed for changes in alkaline phosphatase activity (APA). To test for effects on BMP signaling, subconfluent cells were transfected with BMP/Smad reporter constructs and treated with BMP-2, as described under transient transfections.

ST-2 stromal and MC3T3 osteoblastic cell lines

ST-2 cells, cloned stromal cells isolated from bone marrow of BC8 mice, and MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells derived from mouse calvariae, were grown in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 C in α-MEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS (33,34). Cells were plated at a density of 104 cells/cm2 and to down-regulate Nov expression, subconfluent cells were transfected with small interfering (si)RNAs as described under RNAi. Cells were examined for effects on APA and BMP/Smad reporter activity, as described under primary osteoblast cell cultures and transient transfections.

Osteoclast differentiation assay

Bone marrow stromal cells were recovered by centrifugation of femurs and tibiae that were removed aseptically from 4-wk-old Nov null mice and wild-type littermate controls, after a modification of a previously described protocol (30). Cells were incubated for 2 h in α-MEM containing 15% FBS at 37 C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Nonadherent cells were collected and plated in fresh medium containing 10 nm 1.25 dihydroxyvitamin vitamin D3 (BioMol International, Plymouth Meeting, PA) (35). After 6 d, cells were fixed and stained for tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich).

RNAi

To down-regulate Nov expression in vitro, a 19-mer double-stranded siRNA targeted to the murine Nov mRNA sequence was obtained commercially, and a scrambled 19-mer siRNA with no homology to known mouse or rat sequences was used as a control (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) (36,37). Nov or scrambled siRNA, both at 20 nm, were transfected into subconfluent ST-2 and MC3T3 cells using siLentFect lipid reagent, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cells were allowed to recover for 24 h before the determination of APA or transactivation experiments. To ensure adequate Nov down-regulation, total RNA was extracted after the transfection of siRNAs and mRNA levels determined by real-time RT-PCR.

APA

APA was determined in cells extracted with 0.5% Triton X-100 by the hydrolysis of p-nitrophenyl phosphate to p-nitrophenol measured by spectroscopy at 405 nm after 10 min of incubation at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Sigma-Aldrich). Data are expressed as picomoles of p-nitrophenol released per minute per microgram of protein. The total protein content was determined in cell extracts by the DC protein assay, in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad).

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cell cultures and mRNA levels determined by real-time RT-PCR (26,27). For this purpose, 5 μg of RNA were reverse transcribed using SuperScript III platinum two-step quantitative RT-PCR kit (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and amplified in the presence of 5′-GAACCACAGACTGGCATTTGCATGG[FAM]TC-3′ and 5′-CAAACTTCTCTCCGTTGCGGTA-3′ primers for Nov; 5′-CGGTTAGGGCGTCTCCACAGTAAC[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-CTTGGAGAGGGCCACAAAGG-3′ primers for alkaline phosphatase; 5′-CGAAGTTACATGACACTGGGCTT[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-CCCAGCACAACTCCTCCCTA-3′ primers for osteocalcin; 5′-CACTCCGGGAAATGCTGCAAGGAG[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-GTTGGGTCTGGGCCAAATGT-3′ primers for CTGF; 5′-CGGTATGCTCCAGTGTCAAGAAATAC[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-GCATCTTCACAGTTCTGGTCTGC-3′ primers for Cyr 61; 5′-CGAAGTTACATGACACTGGGCTT[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-TCCAGGAGTTAAGTGATTTGCTCA-3′ primers for WISP-1; 5′-CACAGCAAGAGGATGACGGGAGCTG[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-CGTCATCACAGCGGCACAA-3′ primers for WISP-2; 5′-CGAACCGGATAATGTGAAGTTCAAGGTT[FAM]G-3′ and 5′-CTGCTTCAGCTTCTCTGCCTTT-3′ primers for ribosomal protein L38 (RPL38), and platinum quantitative PCR SuperMix-UDG (Invitrogen) at 60 C for 45 cycles.

Transcript copy number was estimated by comparison with a standard curve constructed using Nov, alkaline phosphatase, WISP-1, WISP-2, and RPL38 (all from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), Cyr 61 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA), CTGF (R. P. Rysek, Bristol Myers Squibb Pharmaceutical Research Institute, New York, NY), or osteocalcin cDNAs (J. B. Lian, Department of Cell Biology, University of Massachusetts, Worcester, MA) (38,39). Reactions were conducted in a 96-well spectrofluorometric thermal iCycler (Bio-Rad), and fluorescence was monitored during every PCR cycle at the annealing step. Data are expressed as copy number corrected for rpl38.

Transient transfections

To determine changes in BMP-2 signaling, a construct containing 12 copies of a Smad 1/5/8 consensus sequence linked to an osteocalcin minimal promoter and a luciferase reporter gene (12×SBE-Oc-pGL3; M. Zhao, Vanderbilt Center for Bone Biology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville, TN) was tested in transient transfection experiments (40). Osteoblasts were cultured to 70% confluence and transiently transfected with the indicated construct using FuGENE6 (3 μl FuGENE/2 μg DNA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). A CMV-directed β-galactosidase expression construct (CLONTECH, San Jose, CA) was used to control for transfection efficiency. Cells were exposed to the FuGENE-DNA mix for 16 h and transferred to serum-free medium for 8 h, treated with BMP-2 for 24 h, and harvested. Luciferase and β-galactosidase activities were measured using an Optocomp luminometer (MGM Instruments, Hamden, CT). Luciferase activity was corrected for β-galactosidase activity.

Surface plasmon resonance

Surface plasmon resonance was used to measure Nov/BMP interactions (41,42). A kinetic analysis of Nov binding to BMP-2 was conducted. Pure BMP-2 (Pepro Tech, Rocky Hill, NJ) was immobilized onto Biacore sensor chips (CM5) and the binding experiments performed on a Biacore 3000 SPR at Acceleron Pharmaceuticals. Pure Nov protein (Pepro Tech) was injected at different concentrations and the kinetic binding constants (kon and koff) between Nov and the immobilized BMP-2 measured, and the equilibrium binding constant determined.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as means ± sem. Statistical differences were determined by unpaired Student’s t test or ANOVA.

Results

Nov null mice

To study Nov null mice, Nov+/− mice were intermated to obtain Nov−/− mice and wild-type littermate controls. The Nov null genotype and the deletion of the neo cassette were documented by PCR of tail extracts from Nov null mice (Fig. 1). The Nov null state was confirmed by determining Nov mRNA levels in calvarial extracts. Nov transcripts were detectable in calvariae from wild-type controls but were virtually undetectable in calvariae from Nov null mice from 1 to 10 months of age (Fig. 1).

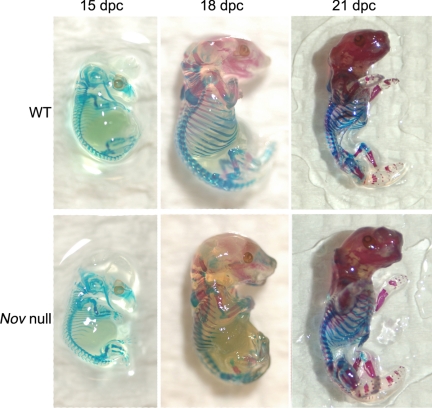

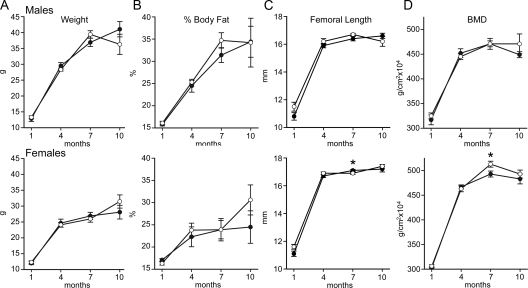

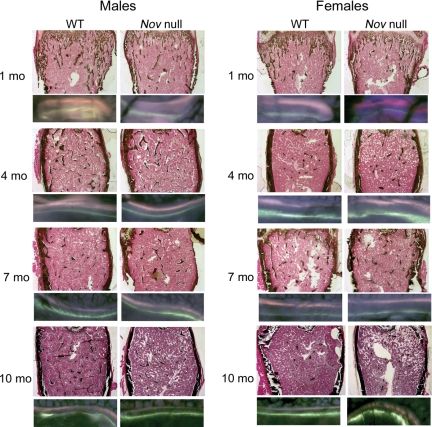

Nov null mice appeared normal and not different from wild-type littermate controls. Skeletal staining of Nov null and control embryos at 15 and 18 d after coitum and newborns did not reveal obvious differences between control and experimental mice (Fig. 2). Contact radiography of Nov null mice at 1, 4, 7, and 10 months of age revealed no apparent skeletal abnormalities, and their skeletons were not different from those of control mice (not shown). Nov null mice had normal body weight, percent body fat, femoral length, and BMD at 1, 4, 7, and 10 months of age (Fig. 3). A 4% decrease in BMD was noted in 7-month-old female Nov null mice due to a small decrease in bone mineral content and a small increase in bone area. Static and dynamic histomorphometric analysis performed in 1-, 4-, 7-, and 10-month-old mice revealed modest phenotypic differences between Nov null mice of both sexes and wild-type controls (Fig. 4 and Table 1).

Figure 2.

Representative skeletal developmental phenotype of embryos at 15 and 18 d post coitum (dpc) and newborns stained with Alcian blue and alizarin red to demonstrate cartilage and mineralized skeletal structures in Nov null (lower panel) and wild-type (WT) controls (upper panel).

Figure 3.

Weight, body composition (percent fat), femoral length, and BMD in male (upper panels) and female (lower panels) Nov null mice (filled circles) and wild-type littermate controls (open circles). The weight in grams (A), percent body fat (B), femoral length in millimeters (C), and total BMD (grams per square centimeter, D) at 1, 4, 7, and 10 months of age are shown. Values are means ± sem, n = 7–9. *, Significantly different from control mice (P < 0.05). Femoral length was 0.2 mm longer in 7-month-old female Nov null mice than controls.

Figure 4.

Representative histological sections and calcein/demeclocycline labeling of bone femoral sections from 1-, 4-, 7-, and 10-month-old Nov null mice and wild-type (WT) littermate controls. Sections were stained with von Kossa without counterstain (final magnification, ×40) or unstained and examined under fluorescence microscopy (final magnification, ×400). mo, Months.

Table 1.

Femoral histomorphometry of 1-, 4-, and 7-month-old male and female Nov null mice and wild type littermate controls

| 1 month old

|

4 months old

|

7 months old

|

10 months old

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Nov null | Wild type | Nov null | Wild type | Nov null | Wild type | Nov null | |

| Males | ||||||||

| Bone volume/tissue volume (%) | 6.6 ± 0.9 | 6.8 ± 0.8 | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 10.0 ± 0.8 | 7.2 ± 0.5 | 6.5 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.6 |

| Trabecular separation (μm) | 160 ± 16 | 149 ± 27 | 126 ± 6 | 117 ± 6 | 165 ± 10 | 184 ± 8 | 220 ± 11 | 224 ± 14 |

| Trabecular number (mm−1) | 6.4 ± 0.7 | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 7.4 ± 0.3 | 7.8 ± 0.3 | 5.7 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.3 |

| Trabecular thickness (μm) | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 12.2 ± 0.3 | 12.7 ± 0.6 | 12.5 ± 0.3 | 12.6 ± 0.3 | 11.7 ± 0.1 | 11.7 ± 0.6 |

| Osteoblast surface/bone surface (%) | 21.8 ± 2.0 | 20.5 ± 1.7 | 7.1 ± 1.0 | 9.2 ± 1.9 | 14.5 ± 1.4 | 15.6 ± 1.3 | 16.0 ± 1.5 | 18.2 ± 2.5 |

| Number of osteoblasts/bone perimeter (mm−1) | 42.5 ± 3.8 | 40.3 ± 3.7 | 13.3 ± 1.8 | 15.5 ± 2.6 | 23.6 ± 2.4 | 25.3 ± 2.3 | 25.2 ± 2.8 | 28.7 ± 4.5 |

| Number of osteoblasts/tissue area (mm−2) | 409 ± 32 | 435 ± 58 | 152 ± 20 | 187 ± 26 | 208 ± 16 | 201 ± 13 | 172 ± 23 | 191 ± 26 |

| Osteoclast surface/bone surface (%) | 10.8 ± 0.7 | 11.6 ± 1.2 | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | 4.3 ± 0.5 | 5.5 ± 0.2a | 5.3 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.7 |

| Number of osteoclasts/bone perimeter (mm−1) | 9.5 ± 0.6 | 10.0 ± 1.0 | 8.8 ± 0.7 | 8.1 ± 0.9 | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 5.1 ± 0.2a | 5.7 ± 0.7 | 4.6 ± 0.7 |

| Number of osteoclasts/tissue area (mm−2) | 96 ± 12 | 107 ± 14 | 101 ± 8 | 101 ± 14 | 35 ± 4 | 41 ± 2 | 38 ± 3 | 30 ± 4 |

| Eroded surface/bone surface (%) | 21.7 ± 1.6 | 23.2 ± 2.8 | 24.2 ± 1.3 | 22.7 ± 1.4 | 9.0 ± 0.8 | 11.9 ± 0.4a | 10.8 ± 1.2 | 9.1 ± 1.2 |

| Mineral apposition rate (μm/day) | 1.02 ± 0.07 | 0.87 ± 0.03 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.39 ± 0.02 | 0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 0.32 ± 0.02 |

| Mineralizing surface/bone surface (%) | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 3.8 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.4 | 2.3 ± 0.3 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 3.0 ± 0.9 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 3.4 ± 1.0 |

| Bone formation rate (μm3/μm2 · d) | 0.049 ± 0.009 | 0.033 ± 0.003 | 0.008 ± 0.001 | 0.009 ± 0.001 | 0.009 ± 0.002 | 0.011 ± 0.003 | 0.016 ± 0.003 | 0.012 ± 0.004 |

| Females | ||||||||

| Bone volume/tissue volume (%) | 7.3 ± 0.5 | 4.7 ± 0.7a | 4.8 ± 0.4 | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.4 |

| Trabecular separation (μm) | 131 ± 7 | 233 ± 42a | 211 ± 11 | 244 ± 24 | 491 ± 58 | 475 ± 35 | 783 ± 60 | 833 ± 184 |

| Trabecular number (mm−1) | 7.2 ± 0.3 | 4.7 ± 0.6a | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 | 1.5 ± 0.3 |

| Trabecular thickness (μm) | 10.0 ± 0.4 | 9.9 ± 0.3 | 10.4 ± 0.3 | 10.1 ± 0.4 | 9.7 ± 0.5 | 10.0 ± 0.4 | 11.0 ± 0.6 | 10.9 ± 0.8 |

| Osteoblast surface/bone surface (%) | 22.8 ± 1.6 | 25.1 ± 1.5 | 16.8 ± 2.0 | 15.9 ± 1.2 | 23.3 ± 1.7 | 28.6 ± 3.7 | 15.2 ± 2.6 | 25.5 ± 3.7a |

| Number of osteoblasts/bone perimeter (mm−1) | 46.6 ± 2.9 | 51.0 ± 3.3 | 27.6 ± 3.5 | 26.6 ± 1.9 | 37.8 ± 2.4 | 44.6 ± 5.4 | 25.2 ± 4.7 | 41.2 ± 6.5b |

| Number of osteoblasts/tissue area (mm−2) | 528 ± 40 | 380 ± 58a | 203 ± 30 | 176 ± 23 | 128 ± 15 | 151 ± 25 | 51 ± 10 | 104 ± 25b |

| Osteoclast surface/bone surface (%) | 13.3 ± 0.8 | 15.0 ± 0.8 | 8.8 ± 0.7 | 9.7 ± 1.0 | 6.7 ± 0.6 | 6.2 ± 0.6 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 7.6 ± 0.7 |

| Number of osteoclasts/bone perimeter (mm−1) | 11.6 ± 0.6 | 13.2 ± 0.7 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 9.5 ± 1.0 | 6.2 ± 0.4 | 5.7 ± 0.5 | 6.8 ± 1.0 | 6.9 ± 0.6 |

| Number of osteoclasts/tissue area (mm−2) | 130 ± 7 | 95 ± 11 | 61 ± 4 | 62 ± 8 | 21 ± 3 | 19 ± 3 | 13.9 ± 2.3 | 16.6 ± 3.7 |

| Eroded surface/bone surface (%) | 25.4 ± 1.2 | 29.2 ± 1.8 | 25.1 ± 1.7 | 26.4 ± 2.1 | 13.0 ± 1.2 | 11.9 ± 1.0 | 14.4 ± 2.2 | 13.9 ± 1.2 |

| Mineral apposition rate (μm/day) | 1.04 ± 0.05 | 1.13 ± 0.08 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | 0.53 ± 0.06 | 0.50 ± 0.03 | 0.54 ± 0.03 | 0.37 ± 0.03 | 0.44 ± 0.02 |

| Mineralizing surface/bone surface (%) | 4.2 ± 0.4 | 5.0 ± 0.4 | 2.7 ± 0.5 | 2.1 ± 0.4 | 6.3 ± 0.9 | 4.1 ± 0.9 | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 19.5 ± 6.1a |

| Bone formation rate (μm3/μm2 · d) | 0.044 ± 0.005 | 0.056 ± 0.005 | 0.014 ± 0.003 | 0.011 ± 0.002 | 0.031 ± 0.004 | 0.023 ± 0.006 | 0.020 ± 0.007 | 0.080 ± 0.023a |

Bone histomorphometry was performed on femurs from 1-, 4-, 7-, and 10-month-old male and female Nov null and wild-type littermate controls. Values are means ± sem; n = 4–9.

Significantly different from controls (P < 0.05, by unpaired t test).

Significantly different from controls (P < 0.07, by unpaired t test).

A modest decrease in bone volume/tissue volume secondary to a decrease in trabecular number was observed in 1-month-old female Nov null mice, but the osteopenia was transient and not observed in 4-, 7-, or 10-month-old female mice or in male mice. An increase in osteoblast surface/bone surface, mineralizing surface, and bone formation was observed in 10-month-old female Nov null mice but not in male mice. An increase in osteoclasts/perimeter and eroded surface was noted in male Nov null mice at 7 months of age. These changes were modest and not observed in female mice. There was a trend toward higher serum levels of the marker of bone remodeling CTX in 4- and 7-month-old Nov null mice when compared with control mice, although the levels were significantly different only in 4-month-old male mice. Serum concentrations of CTX (means ± sem; n = 3) were 11.6 ± 1.5 ng/ml in control and 17.6 ± 2.1 ng/ml in Nov null male mice (P < 0.05) and 24.1 ± 6.4 ng/ml in control and 32.5 ± 17.3 ng/ml in Nov null female mice at 4 months of age. At 7 months of age, serum concentrations of CTX (n = 3) were 20.3 ± 2.3 ng/ml in control and 24.7 ± 4.4 ng/ml in Nov null male mice and 19.3 ± 1.5 ng/ml in control and 23.9 ± 3.7 ng/ml in Nov null female mice. In accordance with the results obtained by bone histomorphometry, μCT analysis revealed only minor differences between Nov null mice and control mice (Table 2). In summary, Nov null mice exhibit modest skeletal abnormalities, and although an increase in osteoblast surface, bone formation, and bone remodeling was noted in selected mice, Nov appears to be relatively dispensable for adult skeletal homeostasis.

Table 2.

Femoral bone microarchitecture assessed by μCT of 1-, 4-, and 7-month-old male and female Nov null mice and wild-type littermate controls

| 1 month old

|

4 months old

|

7 months old

|

10 months old

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild type | Nov null | Wild type | Nov null | Wild type | Nov null | Wild type | Nov null | |

| Males | ||||||||

| Bone volume/tissue volume (%) | 3.9 ± 0.4 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | 8.6 ± 0.6 | 7.7 ± 1.1 | 8.7 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 0.3 | 5.1 ± 0.5 | 4.8 ± 0.5 |

| Trabecular separation (μm) | 410 ± 40 | 420 ± 30 | 210 ± 10 | 220 ± 10 | 230 ± 10 | 240 ± 10 | 260 ± 10 | 270 ± 10 |

| Trabecular number (mm−1) | 2.5 ± 0.3 | 2.4 ± 0.2 | 4.6 ± 0.1 | 4.6 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.1 | 3.8 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.1 |

| Trabecular thickness (μm) | 39 ± 1 | 41 ± 2 | 44 ± 1 | 43 ± 1 | 48 ± 3 | 46 ± 1 | 47 ± 2 | 50 ± 2 |

| Connectivity density (1/mm3) | 23.7 ± 6.7 | 22.4 ± 12.2 | 69.7 ± 7.5 | 62.1 ± 16.1 | 50.5 ± 5.6 | 29.3 ± 4.1a | 21.6 ± 5.4 | 13.4 ± 4.6 |

| Structure model index | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 3.2 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.4 ± 0.1 | 3.6 ± 0.1 |

| Cortical thickness (μm) | 125 ± 4 | 131 ± 4 | 196 ± 5 | 188 ± 4 | 207 ± 2 | 204 ± 5 | 200 ± 13 | 193 ± 3 |

| Females | ||||||||

| Bone volume/tissue volume (%) | 4.8 ± 1.1 | 2.9 ± 1.3 | 3.4 ± 0.6 | 4.4 ± 0.6 | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 1.7 | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 ± 0.5 |

| Trabecular separation (μm) | 400 ± 50 | 390 ± 50 | 320 ± 10 | 290 ± 10 | 420 ± 10 | 410 ± 10 | 480 ± 30 | 450 ± 10 |

| Trabecular number (mm−1) | 2.6 ± 0.3 | 2.7 ± 0.3 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.5 ± 0.1 | 2.1 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.1 |

| Trabecular thickness (μm) | 39 ± 1 | 36 ± 2 | 40 ± 1 | 41 ± 1 | 38 ± 3 | 41 ± 3 | 60 ± 5 | 50 ± 2 |

| Connectivity density (1/mm3) | 48.2 ± 16.2 | 23.4 ± 14.3 | 10.5 ± 4.3 | 19.6 ± 7.5 | 1.1 ± 1.5 | 2.6 ± 5.6 | −0.03 ± 0.33 | 2.66 ± 5.5 |

| Structure model index | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.1 | 4.1 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.2 | 4.3 ± 0.2 | 4.0 ± 0.1 |

| Cortical thickness (μm) | 126 ± 2 | 133 ± 2a | 199 ± 4 | 196 ± 5 | 227 ± 7 | 217 ± 2 | 227 ± 9 | 197 ± 13a |

Bone μCT was performed on femurs from 1-, 4-, 7-, and 10-month-old male and female Nov null and wild-type littermate controls. Voxel size used for analysis was 12 μ m. Values are means ± sem; n = 3–5.

Significantly different from controls (P < 0.05 by unpaired t test).

Primary osteoblast cultures

Previous work revealed marked effects of Nov overexpression in osteoblasts in vivo and in vitro (5). To investigate whether Nov played a role in osteoblastic cell function, calvarial osteoblasts from Nov null mice and wild-type controls of both sexes were cultured for up to 2 wk after confluence. Nov inactivation was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR, and Nov transcripts were virtually undetectable in Nov null cells (Fig. 5). After 14 d of culture, alkaline phosphatase and osteocalcin mRNA levels were about 2-fold higher in Nov null osteoblasts than control cells (Fig. 5). Accordingly, Nov null osteoblasts exhibited a greater response to BMP-2 when tested for immediate effects on alkaline phosphatase mRNA, APA, and the transactivation of the BMP/Smad reporter 12×SBE-Oc-pGL3 transfected into osteoblasts (Fig. 5). BMP-2 treatment for 24 h did not have an effect on osteocalcin mRNA levels in control or Nov null osteoblasts (data not shown). Nov inactivation did not result in changes in mRNA expression of other members of the CCN family of genes. Transcript levels of CTGF, Cyr 61, WISP-1, and WISP-2 were not different between wild-type and Nov null osteoblasts cultured for up to 2 wk after confluence (data not shown). WISP-3 was not measured because it is not detectable in osteoblast cultures (8).

Figure 5.

Effect of Nov inactivation on osteoblast differentiation in calvarial osteoblasts harvested from Nov null mice (black bars or undetectable) and wild-type controls (white bars) of both sexes. A, Calvarial osteoblasts were cultured for 14 d after confluence; total RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified by real-time RT-PCR. Data are expressed as Nov, alkaline phosphatase (Ap), and osteocalcin copy number, corrected for rpl38 expression. B and C, Calvarial osteoblasts were cultured to confluence, exposed to control medium or BMP-2 at 3.3 nm for 24 h (B) or 0.03 to 3.3 nm for 72 h (C), and RNA levels determined by real-time RT-PCR (B) and APA quantified (C). In B, data are expressed as Nov and alkaline phosphatase copy number and corrected for rpl38 expression. In C, APA is expressed as nanomoles of p-nitrophenol per minute per microgram of total protein. D, Cells were cultured to subconfluence and transfected with 12×SBE-Oc-pGL3 and a CMV/β-galactosidase expression vector. After 16 h, cells were switched to serum-free DMEM and treated or not with BMP-2 at the indicated doses for 24 h. Data shown represent luciferase/β-galactosidase activity. Values are means ± sem; n = 4 (A and B) and n = 6 (C and D). *, Significantly different from control (P < 0.05).

Down-regulation of Nov

To confirm the results observed in Nov null cells, Nov mRNA levels were down-regulated by RNAi in ST-2 stromal and MC3T3 osteoblastic cell lines. Nov down-regulation was confirmed by real-time RT-PCR, and Nov transcripts were reduced by 45–95% in cells transfected with Nov siRNA, when compared with control cells transfected with scrambled siRNA (Fig. 6). The down-regulation of Nov enhanced the effect of BMP-2 on APA and the transactivation of the BMP/Smad reporter construct 12×SBE-Oc-pGL3 in ST-2 and MC3T3 cells. These results confirm that Nov opposes the effects of BMP-2 and plays a role in osteoblastic function, explaining the increased osteoblast surface and bone formation observed in 10-month-old female mice.

Figure 6.

Effect of Nov down-regulation by RNAi on BMP signaling and activity in ST-2 stromal (left panels) and MC3T3 (right panels) cell lines transfected with scrambled siRNA (white bars) or Nov siRNA (black bars). A and C, Cells were cultured to subconfluence and transfected with 12×SBE-Oc-pGL3 and a CMV/β-galactosidase expression vector. After 16 h, cells were switched to serum-free α-MEM and treated with BMP-2 at the indicated doses for 24 h. Data shown represent luciferase/β-galactosidase activity for cells transfected with control scrambled siRNA or Nov siRNA. B and D, Cells were cultured to confluence and treated with BMP-2 at the indicated doses for 72 h and examined for APA (nanomoles per minute per microgram protein). Total RNA obtained from parallel cultures was reversed transcribed and amplified by real-time RT-PCR. The table on the left corresponds to RNA obtained in parallel to results from one experiment shown in A and B. Data on MC3T3 cells were obtained from two experiments, and tables on the right are placed immediately below their respective experiments shown in C and D. Data are expressed as Nov copy number corrected for rpl38 and shown as means for two or three observations. Bars (A–D) represent means ± sem for six observations. *, Significantly different form wild-type controls (P < 0.05).

Osteoclast differentiation

To investigate whether Nov played a role in osteoclast differentiation, bone marrow stromal cells from Nov null mice and wild-type littermate controls of both sexes were cultured, and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase-positive cells containing three or more nuclei were considered osteoclasts. The number of osteoclasts was (means ± sem; n = 12) 37.5 ± 0.3 cells/cm2 in control cultures and 108.3 ± 0.6 cells/cm2 in Nov null cultures (P < 0.05). These results are in agreement with the increased osteoclast surface observed in 7-month-old male mice and a suppressive effect of Nov in osteoclast formation.

Surface plasmon resonance

In previous studies, we demonstrated direct interactions between a glutathione-S-transferase (GST)-Nov fusion protein and BMP-2 by GST pull-down experiments (5). To confirm this observation, a kinetic analysis of Nov binding to BMP-2 was performed using surface plasmon resonance. This demonstrated a direct interaction between Nov and BMP-2 and a good fit to 1:1 interaction model between the two proteins (Fig. 7). These observations indicate that Nov binds to BMP-2, explaining the BMP-2 antagonizing activity of Nov in cultures of osteoblasts and cell lines.

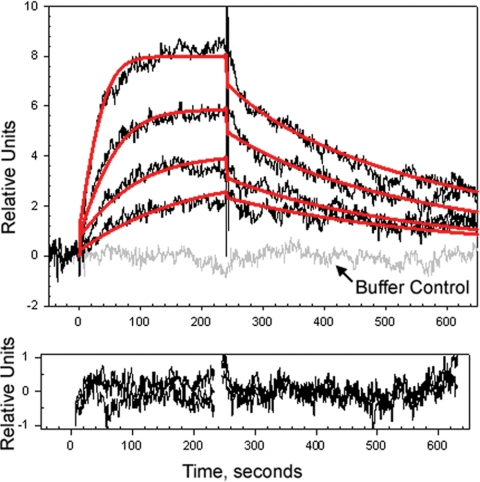

Figure 7.

Kinetic analysis for Nov binding to BMP-2 by surface plasmon resonance. Upper panel, BMP-2 was immobilized at low density on a CM5 chip, and Nov (0.195–1.56 nm) was injected over immobilized BMP-2 at 50 μl/min (black lines). Red solid lines represent global fitting to a Langmuir (1:1) interaction model. Lower panel, Residuals obtained during fitting. Kinetic parameters of Nov binding to BMP-2: kon = 3.72 e7 Ms−1; koff = 3.82 e−3 sec−1; binding constant = 1.04 e−10 m.

Discussion

Our findings demonstrate that Nov null mice exhibit normal skeletal development and growth and only a modest skeletal phenotype between 1 and 10 months of age. Osteoblast surface and mineralizing surface were affected only in 10-month-old female Nov null mice, indicating that this group of animals exhibited a greater bone forming surface. Osteoclast number and bone resorption were enhanced in male Nov null mice at 7 months of age. Accordingly, there was a trend toward higher serum CTX levels in Nov null mice, and these were significantly increased in 4-month-old Nov null male mice, suggesting enhanced bone remodeling. The importance of the latter finding is not clear, although Nov could play a role in bone resorption by interacting with integrins (11). It is also possible that Nov has direct inhibitory effects on osteoclast formation and bone resorption that are independent of its association with integrins. This is possible in view of the increased osteoclast surface and increased osteoclast formation observed in vitro in the Nov null state.

Direct effects on osteoclast formation also have been reported for Cyr 61, a structurally related CCN protein (43). The sexual dimorphism observed in the skeletal phenotype of Nov null mice probably is due to inherent differences in the skeletal architecture of C57BL/6 mice. In this study we confirm earlier observations demonstrating a more rapid age-dependent decline in trabecular bone volume in female than male mice so that at the same age the bone architecture differs between male and female mice (Tables 1 and 2) (44). This may contribute to the sexual dimorphism noted in Nov null mice. The lack of a pronounced skeletal phenotype is in contrast with a recent report demonstrating abnormal skeletal and cardiac development and cataracts in Nov null mice (17). The Nov null phenotype we report does not duplicate previous findings. There are several differences between the gene-targeting strategy of the Nov locus in the former report and the strategy we used. In the work by Heath et al. (17), exon 3 of Nov was replaced with a TK neomycin selection cassette so that the targeted allele encoded a truncated Nov protein lacking only the von Willebrand type C domain. As a consequence, the truncated Nov protein was expressed at detectable levels in cells from Nov null mice.

Another fundamental difference in the two approaches was that the neo cassette was not removed in the work by Heath et al. (17), and the line was maintained in a 129SvJ genetic background, and the uniformity of the genetic composition was not stated. In the present report, the coding region of Nov was deleted in its entirety, the neo cassette excised by Cre recombination and the line backcrossed into a uniform C57BL/6 genetic background. These are critical differences because truncated proteins can have unexpected biological effects, and neo selection cassettes can alter the transcription of neighboring and distant genes and modify a phenotype (18,19). Furthermore, phenotypes are highly dependent on the genetic composition of the mouse line, and the genetic uniformity of experimental and control groups is essential for the proper characterization of the phenotype (45,46,47).

The in vivo phenotype we describe indicates that Nov is nearly dispensable for adult skeletal homeostasis. Although the mRNA levels of Cyr 61, CTGF, WISP-1, and WISP-2 were not modified in osteoblasts by the Nov null state, they were detectable and it is possible that a member of the CCN family of genes could compensate for the absence of Nov. In contrast to the modest phenotype described, the transgenic overexpression of Nov under the control of the osteocalcin promoter causes osteopenia secondary to decreased bone formation. This would indicate that under conditions of Nov induction or excess, Nov could play a role in bone remodeling. The inactivation and down-regulation of Nov sensitizes osteoblastic cells to the actions of BMP-2 and enhances the expression of markers of osteoblastic function. It is important to note that the inactivation of Nov in vitro is congruent with the effects of Nov overexpression because Nov inhibits osteoblastogenesis, BMP-2 signaling, and activity. It is not clear why the sensitization of BMP-2 activity after inactivation of Nov in vitro is translated only into a modest phenotype in vivo. Ten-month-old female Nov null mice exhibited increased osteoblast and mineralizing surfaces, but these changes were not detected at younger ages or in male mice and were not translated into an increase in trabecular bone volume. This may be in part because 10-month-old female mice have limited amounts of trabecular bone and their femoral structure is mostly composed of cortical bone so that an increase in trabecular bone volume could not occur or be detected in the Nov null state. It is possible that the activity of BMP-2 is not sufficiently or permanently enhanced to cause a consistent phenotype or that BMP-2 does not have an effect on adult skeletal homeostasis. Whereas inactivation of BMP-2 causes skeletal fragility, the consequences of its overexpression in bone have not been reported (48). Overexpression of BMP-4, which shares structural and biological properties with BMP-2, under the control of the type I collagen promoter causes osteopenia secondary to an increase in osteoclast number and bone resorption (49). Therefore, the increased bone resorption observed in 7-month-old male mice could represent a level of increased BMP activity that was not sufficient to cause the osteopenia observed in BMP-4 transgenics.

The in vitro findings in Nov null cells were confirmed by in vitro experiments down-regulating Nov by RNAi. Nov inactivation caused an increased expression of osteoblast gene markers in calvarial osteoblasts, and the down-regulation of Nov in MC3T3 and ST-2 stromal cells caused increased APA, indicating an inhibitory role of Nov on osteoblastic cell differentiation/function. The mechanism of the impaired osteoblastic differentiation/function could involve the binding and sequestration of BMPs by Nov in the bone environment because our results confirm direct interactions between Nov and BMP-2. Furthermore, cells overexpressing Nov inhibit BMP actions, whereas cells from Nov null mice exhibit an increased responsiveness to BMP-2 activity. In accordance with previous observations, we noted a modest decrease in Nov mRNA levels in the presence of BMP-2 in MC3T3 cells, whereas Nov expression was increased by BMP-2 in ST-2 cells (8). This differential regulation may be related to different stages of cell maturation and did not preclude down-regulation of Nov by RNAi and as a consequence the sensitization to BMP effects in either cell type.

The mechanism of action of Nov entails the inhibition of BMP-2 activity by direct binding of Nov to BMP-2, as demonstrated previously by GST pull-down experiments and confirmed by surface plasmon resonance in the current studies. These interactions appear to occur in the extracellular compartment, and this also is suggested by experiments in which the addition of Nov protein to the culture medium decreases BMP-2 signaling and activity in osteoblastic cells (5). Other CCN proteins appear to act by similar mechanisms. CTGF binds BMPs, and osteoblasts and stromal cells from CTGF transgenics have impaired BMP signaling and activity (4,6). This is not surprising in view of the structural similarities among the CCN proteins and between CCN proteins and classic BMP antagonists, such as twisted gastrulation and chordin (1,2,3). It is important to note that as in the case of Nov, there are discrepancies in the in vitro and in vivo phenotypes after CTGF overexpression (6,50). It is apparent that the signals interacting with CCN proteins in vitro are not consistently operational in vivo but might be active at selected times under specific circumstances. The inactivation of Ctgf and Cyr61 result in developmental abnormalities, but inactivation of other CCN genes, such as Wisp3, result in no phenotypic manifestations, indicating that selected CCN proteins are dispensable (51,52,53). The ultimate role of CCN proteins in skeletal remodeling has not been established, but they appear to have distinct functions in skeletal tissue. CTGF and Nov seem to act as BMP antagonists, whereas WISP-1 and Cyr61 mediate stimulatory effects of Wnt on osteoblastogenesis (5,6,54,55).

In conclusion, our studies reveal that Nov interacts with BMP-2 and as a consequence inhibits BMP-2 signaling and activity impairing osteoblastic differentiation/function in vitro, but these effects are not translated into an obvious skeletal phenotype after gene inactivation.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Acceleron Pharmaceuticals for performing surface plasmon resonance; Wyeth Research for BMP-2; M. Zhao for 12×SBE-Oc-pGL3 construct; R. P. Rysek for CTGF cDNA; J. B. Lian for osteocalcin cDNA; Melissa Burton, Trung X. Le, Kristen Parker, and Harold Coombs for technical assistance; and Mary Yurczak for secretarial assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by Grants AR021707 (to E.C.) and AR043618 (to W.G.B.) from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online November 24, 2009

Abbreviations: APA, Alkaline phosphatase activity; BAC, bacterial artificial chromosome; BMD, bone mineral density; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; CCN, Cyr61, connective tissue growth factor, Nov; CMV, cytomegalovirus; μCT, microcomputed tomography; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; CTX, C-terminal cross-linked telopeptide of type I collagen; Cyr 61, cysteine-rich 61; ES, embryonic stem; FBS fetal bovine serum; GST, glutathione-S-transferase; LacZ/Neo, LacZ/neomycin; Nov, nephroblastoma overexpressed; RNAi, RNA interference; RPL38, ribosomal protein L38; SBE, Smad binding element; si, small interfering; Smad, signaling mothers against decapentaplegic; WISP, Wnt inducible secreted protein.

References

- Brigstock DR 2003 The CCN family: a new stimulus package. J Endocrinol 178:169–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brigstock DR, Goldschmeding R, Katsube KI, Lam SC, Lau LF, Lyons K, Naus C, Perbal B, Riser B, Takigawa M, Yeger H 2003 Proposal for a unified CCN nomenclature. Mol Pathol 56:127–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia Abreu J, Coffinier C, Larraín J, Oelgeschläger M, De Robertis EM 2002 Chordin-like CR domains and the regulation of evolutionarily conserved extracellular signaling systems. Gene 287:39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abreu JG, Ketpura NI, Reversade B, De Robertis EM 2002 Connective-tissue growth factor (CTGF) modulates cell signalling by BMP and TGF-β. Nat Cell Biol 4:599–604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rydziel S, Stadmeyer L, Zanotti S, Durant D, Smerdel-Ramoya A, Canalis E 2007 Nephroblastoma overexpressed (Nov) inhibits osteoblastogenesis and causes osteopenia. J Biol Chem 282:19762–19772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerdel-Ramoya A, Zanotti S, Stadmeyer L, Durant D, Canalis E 2008 Skeletal overexpression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) impairs bone formation and causes osteopenia. Endocrinology 149:4374–4381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joliot V, Martinerie C, Dambrine G, Plassiart G, Brisac M, Crochet J, Perbal B 1992 Proviral rearrangements and overexpression of a new cellular gene (nov) in myeloblastosis-associated virus type 1-induced nephroblastomas. Mol Cell Biol 12:10–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parisi MS, Gazzerro E, Rydziel S, Canalis E 2006 Expression and regulation of CCN genes in murine osteoblasts. Bone 38:671–677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu C, Le AT, Yeger H, Perbal B, Alman BA 2003 NOV (CCN3) regulation in the growth plate and CCN family member expression in cartilage neoplasia. J Pathol 201:609–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CG, Leu SJ, Chen N, Tebeau CM, Lin SX, Yeung CY, Lau LF 2003 CCN3 (NOV) is a novel angiogenic regulator of the CCN protein family. J Biol Chem 278:24200–24208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CG, Chen CC, Leu SJ, Grzeszkiewicz TM, Lau LF 2005 Integrin-dependent functions of the angiogenic inducer NOV (CCN3): implication in wound healing. J Biol Chem 280:8229–8237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto K, Yamaguchi S, Ando R, Miyawaki A, Kabasawa Y, Takagi M, Li CL, Perbal B, Katsube K 2002 The nephroblastoma overexpressed gene (NOV/ccn3) protein associates with Notch1 extracellular domain and inhibits myoblast differentiation via Notch signaling pathway. J Biol Chem 277:29399–29405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu CT, Bechberger JF, Ozog MA, Perbal B, Naus CC 2004 CCN3 (NOV) interacts with connexin43 in C6 glioma cells: possible mechanism of connexin-mediated growth suppression. J Biol Chem 279:36943–36950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellhaus A, Dong X, Propson S, Maass K, Klein-Hitpass L, Kibschull M, Traub O, Willecke K, Perbal B, Lye SJ, Winterhager E 2004 Connexin43 interacts with NOV: a possible mechanism for negative regulation of cell growth in choriocarcinoma cells. J Biol Chem 279:36931–36942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecanda F, Warlow PM, Sheikh S, Furlan F, Steinberg TH, Civitelli R 2000 Connexin43 deficiency causes delayed ossification, craniofacial abnormalities, and osteoblast dysfunction. J Cell Biol 151:931–944 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont J, Jacques C, Le Dreau G, Calhabeu F, Thibout H, Dubois C, Berenbaum F, Laurent M, Martinerie C 2005 New target genes for NOV/CCN3 in chondrocytes: TGF-β2 and type X collagen. J Bone Miner Res 20:2213–2223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heath E, Tahri D, Andermarcher E, Schofield P, Fleming S, Boulter CA 2008 Abnormal skeletal and cardiac development, cardiomyopathy, muscle atrophy and cataracts in mice with a targeted disruption of the Nov (Ccn3) gene. BMC Dev Biol 8:18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson EN, Arnold HH, Rigby PW, Wold BJ 1996 Know your neighbors: three phenotypes in null mutants of the myogenic bHLH gene MRF4. Cell 85:1–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham CT, MacIvor DM, Hug BA, Heusel JW, Ley TJ 1996 Long-range disruption of gene expression by a selectable marker cassette. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:13090–13095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela DM, Murphy AJ, Frendewey D, Gale NW, Economides AN, Auerbach W, Poueymirou WT, Adams NC, Rojas J, Yasenchak J, Chernomorsky R, Boucher M, Elsasser AL, Esau L, Zheng J, Griffiths JA, Wang X, Su H, Xue Y, Dominguez MG, Noguera I, Torres R, Macdonald LE, Stewart AF, DeChiara TM, Yancopoulos GD 2003 High-throughput engineering of the mouse genome coupled with high-resolution expression analysis. Nat Biotechnol 21:652–659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith MR, Natarajan D, Taylor LB, Choi CP, Martinerie C, Perbal B, Schofield PN, Boulter CA 1996 Genomic structure and chromosomal mapping of the mouse nov gene. Genomics 38:425–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan K, Williamson R, Zhang Y, Stewart AF, Ioannou PA 1999 Efficient and precise engineering of a 200 kb β-globin human/bacterial artificial chromosome in E. coli DH10B using an inducible homologous recombination system. Gene Ther 6:442–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XW, Model P, Heintz N 1997 Homologous recombination based modification in Escherichia coli and germline transmission in transgenic mice of a bacterial artificial chromosome. Nat Biotechnol 15:859–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Buchholz F, Muyrers JP, Stewart AF 1998 A new logic for DNA engineering using recombination in Escherichia coli. Nat Genet 20:123–128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauer B, Henderson N 1988 Site-specific DNA recombination in mammalian cells by the Cre recombinase of bacteriophage P1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 85:5166–5170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarenko I, Lowe B, Darfler M, Ikonomi P, Schuster D, Rashtchian A 2002 Multiplex quantitative PCR using self-quenched primers labeled with a single fluorophore. Nucleic Acids Res 30:e37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazarenko I, Pires R, Lowe B, Obaidy M, Rashtchian A 2002 Effect of primary and secondary structure of oligodeoxyribonucleotides on the fluorescent properties of conjugated dyes. Nucleic Acids Res 30:2089–2195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien TP, Metallinos DL, Chen H, Shin MK, Tilghman SM 1996 Complementation mapping of skeletal and central nervous system abnormalities in mice of the piebald deletion complex. Genetics 143:447–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagy TR, Prince CW, Li J 2001 Validation of peripheral dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for the measurement of bone mineral in intact and excised long bones of rats. J Bone Miner Res 16:1682–1687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazzerro E, Pereira RC, Jorgetti V, Olson S, Economides AN, Canalis E 2005 Skeletal overexpression of gremlin impairs bone formation and causes osteopenia. Endocrinology 146:655–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parfitt AM, Drezner MK, Glorieux FH, Kanis JA, Malluche H, Meunier PJ, Ott SM, Recker RR 1987 Bone histomorphometry: standardization of nomenclature, symbols, and units. Report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res 2:595–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy TL, Centrella M, Canalis E 1988 Further biochemical and molecular characterization of primary rat parietal bone cell cultures. J Bone Miner Res 3:401–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka E, Yamaguchi A, Hirose S, Hagiwara H 1999 Characterization of osteoblastic differentiation of stromal cell line ST2 that is induced by ascorbic acid. Am J Physiol 277:C132–C138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudo H, Kodama HA, Amagai Y, Yamamoto S, Kasai S 1983 In vitro differentiation and calcification in a new clonal osteogenic cell line derived from newborn mouse calvaria. J Cell Biol 96:191–198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JE, Rogers MJ, Halasy JM, Luckman SP, Hughes DE, Masarachia PJ, Wesolowski G, Russell RG, Rodan GA, Reszka AA 1999 Alendronate mechanism of action: geranylgeraniol, an intermediate in the mevalonate pathway, prevents inhibition of osteoclast formation, bone resorption, and kinase activation in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:133–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, Yalcin A, Weber K, Tuschl T 2001 Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 411:494–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp PA 2001 RNA interference—2001. Genes Dev 15:485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian J, Stewart C, Puchacz E, Mackowiak S, Shalhoub V, Collart D, Zambetti G, Stein G 1989 Structure of the rat osteocalcin gene and regulation of vitamin D-dependent expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:1143–1147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouadjo KE, Nishida Y, Cadrin-Girard JF, Yoshioka M, St. Amand J 2007 Housekeeping and tissue-specific genes in mouse tissues. BMC Genomics 8:127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M, Qiao M, Harris SE, Oyajobi BO, Mundy GR, Chen D 2004 Smurf1 inhibits osteoblast differentiation and bone formation in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem 279:12854–12859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe PS, Garrett IR, Schwarz PM, Carnes DL, Lafer EM, Mundy GR, Gutierrez GE 2005 Surface plasmon resonance (SPR) confirms that MEPE binds to PHEX via the MEPE-ASARM motif: a model for impaired mineralization in X-linked rickets (HYP). Bone 36:33–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler J, Vallejo LF, Rinas U, Bilitewski U 2005 Application of an SPR-based receptor assay for the determination of biologically active recombinant bone morphogenetic protein-2. Anal Bioanal Chem 381:1056–1064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockett JC, Schütze N, Tosh D, Jatzke S, Duthie A, Jakob F, Rogers MJ 2007 The matricellular protein CYR61 inhibits osteoclastogenesis by a mechanism independent of αvβ3 and αvβ5. Endocrinology 148:5761–5768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glatt V, Canalis E, Stadmeyer L, Bouxsein ML 2007 Age-related changes in trabecular architecture differ in female and male C57BL/6J mice. J Bone Miner Res 22:1197–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer WG, Donahue LR, Rosen CJ 2002 Genetics and bone. Using the mouse to understand man. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2:225–231 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beamer WG, Shultz KL, Ackert-Bicknell CL, Horton LG, Delahunty KM, Coombs 3rd HF, Donahue LR, Canalis E, Rosen CJ 2007 Genetic dissection of mouse distal chromosome 1 reveals three linked BMD QTL with sex dependent regulation of bone phenotypes. J Bone Miner Res 22:1187–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouxsein ML, Uchiyama T, Rosen CJ, Shultz KL, Donahue LR, Turner CH, Sen S, Churchill GA, Müller R, Beamer WG 2004 Mapping quantitative trait loci for vertebral trabecular bone volume fraction and microarchitecture in mice. J Bone Miner Res 19:587–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji K, Bandyopadhyay A, Harfe BD, Cox K, Kakar S, Gerstenfeld L, Einhorn T, Tabin CJ, Rosen V 2006 BMP2 activity, although dispensable for bone formation, is required for the initiation of fracture healing. Nat Genet 38:1424–1429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Murai J, Yoshikawa H, Tsumaki N 2006 Bone morphogenetic proteins in bone stimulate osteoclasts and osteoblasts during bone development. J Bone Miner Res 21:1022–1033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smerdel-Ramoya A, Zanotti S, Deregowski V, Canalis E 2008 Connective tissue growth factor enhances osteoblastogenesis in vitro. J Biol Chem 283:22690–22699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivkovic S, Yoon BS, Popoff SN, Safadi FF, Libuda DE, Stephenson RC, Daluiski A, Lyons KM 2003 Connective tissue growth factor coordinates chondrogenesis and angiogenesis during skeletal development. Development 130:2779–2791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutz WE, Gong Y, Warman ML 2005 WISP3, the gene responsible for the human skeletal disease progressive pseudorheumatoid dysplasia, is not essential for skeletal function in mice. Mol Cell Biol 25:414–421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo FE, Muntean AG, Chen CC, Stolz DB, Watkins SC, Lau LF 2002 CYR61 (CCN1) is essential for placental development and vascular integrity. Mol Cell Biol 22:8709–8720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French DM, Kaul RJ, D'Souza AL, Crowley CW, Bao M, Frantz GD, Filvaroff EH, Desnoyers L 2004 WISP-1 is an osteoblastic regulator expressed during skeletal development and fracture repair. Am J Pathol 165:855–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Si W, Kang Q, Luu HH, Park JK, Luo Q, Song WX, Jiang W, Luo X, Li X, Yin H, Montag AG, Haydon RC, He TC 2006 CCN1/Cyr61 is regulated by the canonical Wnt signal and plays an important role in Wnt3A-induced osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. Mol Cell Biol 26:2955–2964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]