Abstract

The purpose of this study was to determine whether reactive oxygen species (ROS) promote cardiac angiogenesis following myocardial infarction (MI) and contribute to cardiac repair. Rats with MI were treated with or without antioxidants, tempol and apocynin. Hearts of these rats were collected at days 2, 4, 7 and 14 post-MI. We examined the spatial and temporal relationship between oxidative stress and angiogenesis as well as the potential regulation of ROS in cardiac angiogenesis. We found: (i) following MI, gp91phox, a subunit of NADPH oxidase, a key enzyme for ROS production, was significantly increased in the border zone at day 2, followed by the infarcted myocardium at day 4, peaked at day 7 and declined at day 14, while superoxide dismutase was significantly reduced; (ii) malondialdehyde, a marker of oxidative stress, was significantly increased in the infarcted myocardium at day 7; (iii) pre-existing blood vessels in the infarcted myocardium underwent necrosis post-MI, whereas newly formed vessels appeared at the border zone at day 4, and then extended into the infarcted myocardium, where microvascular density peaked at day 7 and (iv) antioxidant treatment significantly reduced microvascular density in the infarcted myocardium at day 7. These observations suggest that following MI, angiogenesis is mostly active in the infarcted myocardium in the first week, which is temporally and spatially coincident with enhanced ROS. Suppression of angiogenesis by antioxidants indicates that ROS promote angiogenesis in the infarcted myocardium and contribute to cardiac repair. Further studies are required to determine the mechanisms responsible for ROS-mediated cardiac angiogenesis.

Keywords: Angiogenesis, cardiac repair, myocardial infarction, rats, ROS

Angiogenesis is the formation of new capillary blood vessels from existent microvessels. It plays a critical role in various biological processes, such as wound healing, embryological development, the menstrual cycle, inflammation and the pathogenesis of various diseases, such as cancer, diabetic retinopathy and rheumatoid arthritis. Promoting angiogenesis in some circumstances can be beneficial. For example, promotion of angiogenesis can aid in accelerating various physiological processes and treatment of diseases requiring increased vascularization, such as the healing of wounds, fractures, burns, inflammatory diseases, ischaemia in the heart, peripheral vascular diseases and myocardial infarction (MI) (Timar et al. 2001; Kang et al. 2002; Ren et al. 2003).

The regulatory factors of angiogenesis in the repairing tissue have drawn great attention and multiple pro-angiogenetic mediators have been identified, which include vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), fibroblast growth factor (FGF), integrins, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-2/-9, hypoxia-inducible factors, etc. (Conway et al. 2001). Recent studies have further demonstrated that reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a regulatory role in angiogenesis in certain pathological circumstances. ROS include superoxide (O2−) and hydroxyl (OH−), nitric oxide (NO) and non-radical species such as H2O2. There are several potential sources of ROS in cells, including NADPH oxidases, mitochondria, cytochrome P450-based enzymes, xanthine oxidase and uncoupled NO synthases (Dworakowski et al. 2006). Among these, the NADPH oxidase is especially important for O2− production in the repairing tissue (Dworakowski et al. 2006). O2− can rapidly react with NO to form another reactive species peroxynitrite (ONOO−) or convert to H2O2 to form OH−. Living cells have both enzymatic and non-enzymatic defence mechanisms to balance the multitude of oxidative challenges presented to them. The enzymatic subgroup includes superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase and glutathione peroxidase (Young & Woodside 2001). SOD has several isoforms. Among them, Cu/Zn-SOD and Mn-SOD are the most important for cell oxidative defence. SOD catalyses the dismutation of O2− to H2O2, catalase further metabolizes H2O2 to water and oxygen, and glutathione peroxidase reduces free H2O2 to water. Imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant reserve can lead to tissue oxidative stress.

The stimulatory role of ROS in angiogenesis has been shown by in vivo and in vitro studies. The thiol antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine, is reported to attenuate endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis in a tumour model (Cai et al. 1999). Gu et al. (2003) have demonstrated that ROS are required for coronary collateral development in the ischaemic heart. In addition, there is strong correlation between ROS production and neovascularization in balloon-injured arteries (Ruef et al. 1997). ROS have been found to stimulate angiogenic response in the ischaemic reperfused hearts (Maulik & Das 2002). Furthermore, in cardiac endothelial cells, H2O2 induces angiogenic responses such as cell proliferation and tubular morphogenesis (Shono et al. 1996; Yasuda et al. 1999). Abid et al. (2000) have indicated that inhibitors of ROS block serum-stimulated endothelial cell proliferation and migration. Altogether, these findings suggest that ROS stimulate angiogenesis in certain pathological situations.

Following acute MI, myocytes/interstitial cells and blood vessels in the infarcted myocardium undergo necrosis, triggering cardiac angiogenesis and repair. Although oxidative stress has been demonstrated to occur in the infarcted myocardium, whether ROS regulate cardiac angiogenesis following MI, thereby contributing to cardiac repair, remains to be elucidated. In the current study, we sought to determine the spatial and temporal relationship between oxidative stress and angiogenesis as well as the potential regulation of ROS in new vessel formation in the infarcted rat myocardium.

Material and methods

Animal model

Left ventricular anterior transmural MI was created in 8-week-old female SD rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN, USA) by permanent ligation of the left coronary artery with silk ligature (Zhao et al. 2004). Rats were anaesthetized, intubated and ventilated with a rodent respirator. After left thoracotomy, the heart was exposed and 7-0 silk suture placed around the left coronary artery. The vessel was ligated, which resulted in 40–45% left ventricular infarction, the chest closed and lungs re-inflated using positive-end expiratory pressure. Pharmacological intervention with antioxidants was used to suppress O− in the infarcted heart. The following animal groups were included: (i) sham-operated rats, serving as normal controls; (ii) rats with MI and (iii) rats with MI treated with a combination of antioxidants, tempol (a free radical scavenger) (Sigma, St Louis, MO, USA) and apocynin (a NADPH oxidase inhibitor) (Sigma), each 120 mg/kg/day given by gavage twice a day. The treatment was started 2 days before coronary artery ligation. The combined treatment with two antioxidants can suppress ROS production as well as enhance ROS clearance, thus maximizing the antioxidative effect. Animals were killed at days 2, 4, 7 and 14 following surgery (n = 8/time point/group). Hearts were removed, rinsed in cold normal saline, frozen in isopentane with dry ice and kept at −80 °C. This study was approved by the University of Tennessee Health Science Center Animal Care and Use Committee.

Quantitative in situ hybridization

The localization and optical density of cardiac gp91phox mRNA were detected by quantitative in situ hybridization. In brief, cardiac sections (16 μm) were fixed in 4% formaldehyde for 10 min, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and incubated in 0.25% acetic anhydride in 0.1 M TE–HCl for 10 min. The sections were then hybridized overnight with [35S]dATP-labelled DNA probes for gp91phox at 45 °C. The hybridized sections were then washed, dried and subsequently exposed to Kodak Biomax X-ray film. After exposure, the film was developed. Quantification of optical density of gp91phox mRNA in cardiac sections was performed using a computer image analysis system (NIH Image, 1.60) (Zhao et al. 2008).

Western blotting

Cardiac gp91phox, Cu/Zn-SOD and Mn-SOD protein levels were measured using Western blot. Briefly, the left ventricle from the normal heart or the infarcted myocardium from infarcted heart was dissected, homogenized and separated by 12% SDS–PAGE. After electrophoresis, samples were transferred to PVDF membranes and incubated with antibody against gp91phox (kindly provided by Dr Mark T Quinn, Montana State University), Mn-SOD and Cu/Zn-SOD (Sigma). Blots were subsequently incubated with peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma). After washing, the blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence method. The amount of protein detected by each antibody was measured by a computer image analysis system.

Immunohistochemistry

Cardiac expression of CD31 (a marker of vascular endothelial cells) and ED-1 (a marker of macrophages) was detected by immunohistochemistry. Cardiac sections (6 μm) were air-dried, fixed in 10% buffered formalin for 5 min and washed in PBS for 10 min. The sections were then incubated with the primary antibody against CD31 (Sigma) and ED-1 (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature. The sections were then incubated with IgG-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (Sigma) for 1 h at room temperature, washed in PBS for 10 min and incubated with 0.5 mg/ml diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride 2-hydrate + 0.05% H2O2 for 5 min. Negative control sections were incubated with secondary antibody alone (Lu et al. 2004).

Quantification of microvascular density

Microvessels in the infarcted myocardium were detected by immunostaining for CD31. Microvascular density was measured with a computerized image analysing system. The methods generally comprise creating a digital image of a cross section of the heart, determining the surface area of microvessels in the infarcted myocardium, determining the total area of the infarcted myocardium, calculating the ratio of the microvascular area to the total infarcted area and thereby determining the microvascular density of the infarcted myocardium. The digital image of the heart was created using an image processing software (NIH image 1.60) and the image was displayed on a computer screen. CD31 staining in large vessels was disregarded in microvessel quantification. Microvascular density in the infarcted myocardium is expressed as microvascular volume fraction (Samoszuk et al. 2002).

Malondialdehyde (MDA) assay

Myocardium was homogenized. After centrifugation, supernatant MDA concentration was determined colorimetrically using a commercially available kit (Oxis International Inc, Foster City, CA, USA). Duplicate aliquots of supernatant were incubated at 45 °C with 7.7 mM N-methyl-2-phenylindole in acetonitrile/methanol and 15.4 mM methanesulfonic acid. After clarification by centrifugation, absorbance was measured at 586 nm using 1,1,3,3-tetramethoxypropane as a standard (Selektor et al. 2008).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of in situ hybridization data, microvascular density, MDA levels and Western blot data was performed using analysis of variance. Values are expressed as mean ± SEM, with P <0.05 considered significant. Multiple group comparisons among controls and each group were made by Scheffe’s F-test.

Results

Cardiac gp91phox expression

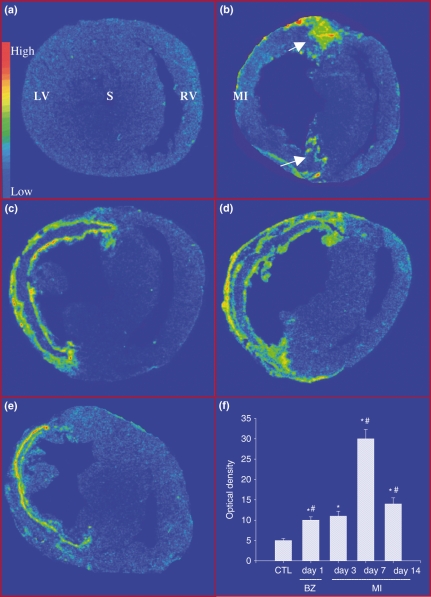

Gp91phox is a subunit of NADPH oxidase, a primary source of ROS in the repairing tissue. Detected by in situ hybridization, a low level of gp91phox mRNA was observed in the left and right ventricles (LV, RV) of the normal heart (Figure 1, panel a). Following MI, gp91phox mRNA was significantly increased at border zone (the region between the infarcted and non-infarcted myocardium) at day 2 (Figure 1, panel b), followed by that at infarcted myocardium at day 4 (Figure 1, panel c). Gp91phox mRNA level in the infarcted myocardium reached peak at day 7 (Figure1, panel d) and declined at day 14, but still was significantly higher than that of controls (Figure 1, panel e). However, gp91phox mRNA level remained unchanged in the non-infarcted myocardium compared with that in controls at all time points. Quantitative gp91phox mRNA levels in the infarcted myocardium are shown in Figure 1, panel f.

Figure 1.

Cardiac gp91phox gene expression: Detected by in situ hybridization, low density of gp91phox mRNA was present in both left and right ventricles (LV, RV) (panel a). Following MI, gp91phox mRNA was significantly increased in border zones (arrows) at day 2 (panel b). It was largely increased in the infarcted myocardium (MI) at day 4 (panel c), peaked at day 7 (panel d) and declined at day 14 (panel e). Gp91phox mRNA remained unchanged in non-infarcted myocardium. Panel F shows temporal response of gp91phox mRNA in the infarcted myocardium. *P< 0.05 vs. controls; #P<0.05 vs. previous time point. S, septum.

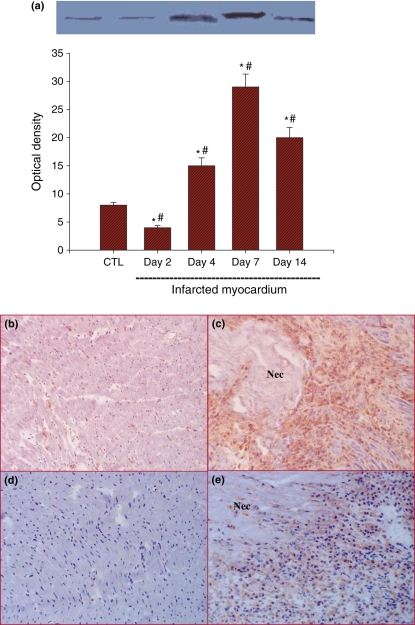

Protein expression of gp91phox in the infarcted myocardium showed a temporal pattern similar to that of gp91phox mRNA. On detection by Western blot, gp91phox protein levels in the infarcted myocardium were reduced at day 2, which then significantly increased at day 4, peaked at day 7 and declined at day 14 (Figure 2, panel a). Immunohistochemistry showed strong gp91phox staining in cells located around the necrotic tissue in the infarcted myocardium at day 7 (Figure 2, panel c). Theses cells also expressed ED-1, a marker of macrophages (Figure 2, panel e), indicating that cells expressing gp91phox are primarily macrophages in the infarcted myocardium. Small amount of interstitial cells expressed gp91phox in the normal myocardium (Figure 2, panel b), whereas macrophages were barely seen in the control heart (Figure 2, panel d).

Figure 2.

Cardiac gp91phox protein expression: Detected by Western blot, gp91phox protein levels in the infarcted myocardium were suppressed at day 2, significantly increased at day 4, peaked at day 7 and then declined at day 14, but still remained significantly higher than that of controls (panel a). Immunohistochemical detection showed strong gp91phox staining in the infarcted myocardium at day 7 (panel c). Cells expressing gp91phox in the infarcted myocardium were also positively labelled with the macrophage marker ED-1 at the same point (panel e). Gp91phox and ED1 expressions in the normal myocardium are shown in panels b and d respectively. Panels b–e: ×200; Nec, necrosis.

Cardiac SOD expression

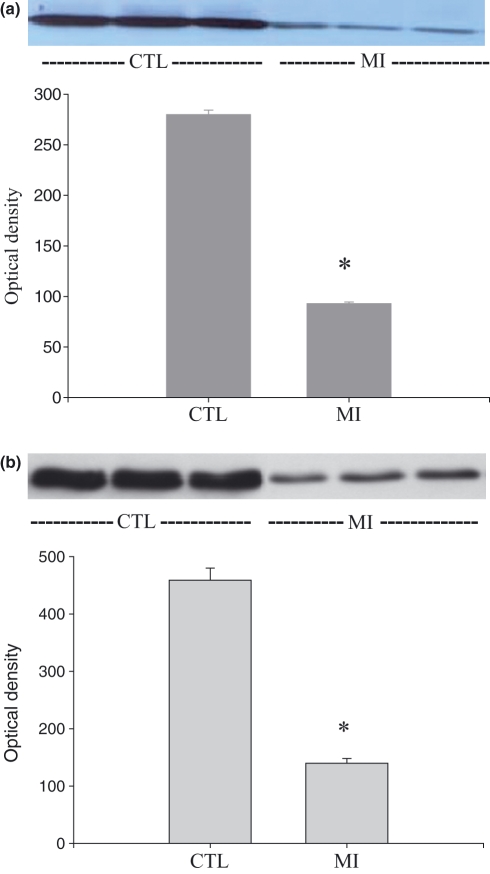

As detected by Western blot, both Mn-SOD and Cu/Zn-SOD protein levels were significantly declined in the infarcted myocardium compared with that of the control hearts at day 7 post-MI (Figure 3, panels a and b respectively).

Figure 3.

Cardiac SOD expression: Mn-SOD and Cu/Zn-SOD protein levels (panels a and b respectively) were significantly reduced in the infarcted myocardium compared with that in controls at day 7 post-MI.

Oxidative stress in the infarcted myocardium

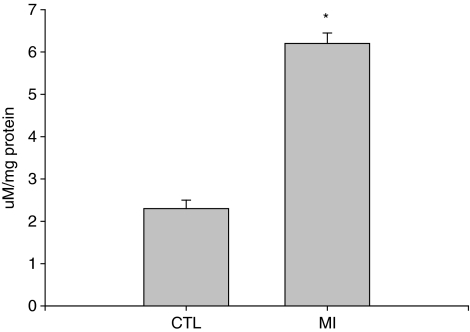

MDA is a marker of oxidative stress. Compared with the normal heart, MDA level was significantly increased in the infarcted myocardium at day 7 (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cardiac MDA content: Compared with that of normal hearts, MDA level was significantly increased at the site of MI at day 7 post-MI.

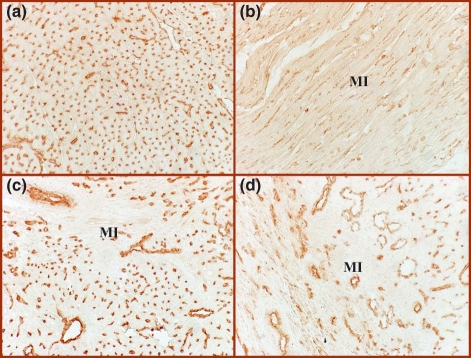

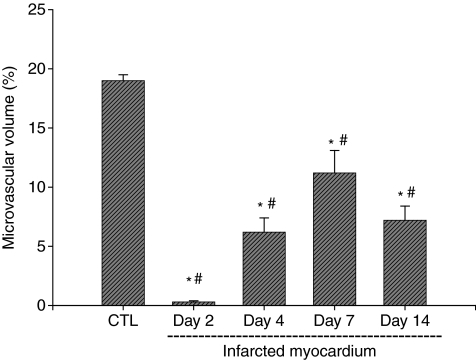

Cardiac angiogenesis following infarction

As detected by immunohistochemical CD31 staining, we observed abundant microvessels in the normal myocardium, including arterioles, capillaries and venules (Figure 5, panel a). Following MI, microvessels underwent necrosis and disappeared from the infarcted myocardium at day 2 (Figure 5, panel b). Newly formed vessels appeared at the border zone and infarcted myocardium as early as day 4 (not shown) and became evident at day 7 (Figure 5, panel c). However, microvascular density declined in the same region at day 14 compared with that at day 7 (Figure 5, panel d). Quantitative microvascular density in the infarcted myocardium is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Cardiac angiogenesis following MI: Detected by immunohistochemical CD31 labelling, abundant microvessels were present in the normal myocardium (panel a). Pre-existing vessels disappeared at day 2 post-MI (panel b). Newly formed microvessels were evident at day 7 (panel c), and then declined at day 14 (panel d), ×200.

Figure 6.

Temporal changes of microvascular volume in the infarcted myocardium.

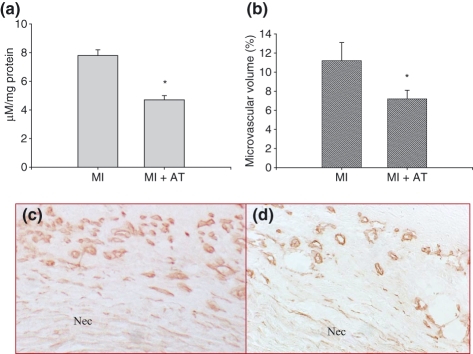

Effect of antioxidant treatment on cardiac oxidative stress and microvascular density

Compared with that of rats with MI, MDA level was significantly suppressed in the infarcted myocardium in rats that received antioxidant treatment (Figure 7, panel a). Antioxidant treatment also significantly suppressed microvascular density in the infarcted myocardium at day 7 post-MI (Figure 7, panels b and d) compared with that of MI rats not receiving treatment (Figure 7, panels b and c).

Figure 7.

Effect of antioxidants on cardiac MDA levels and microvascular density at day 7 post-MI. Antioxidant treatment significantly reduced MDA levels in the infarcted myocardium (panel a). Compared with that of untreated rats with MI (panels b and c), microvascular density in the infarcted myocardium was significantly suppressed (panels b and d). Panels a and b: *P< 0.05 vs. MI group; AT: antioxidants; panels c and d: ×400; Nec: necrosis.

Discussion

The MI has emerged as a major health problem during the past two decades. In the infarcted myocardium, loss of contractile myocardium and blood vessels is induced by MI. Cardiac repair at the site of myocyte loss preserves structural integrity and is integral to the heart’s recovery. Angiogenesis, the growth of new blood vessels, is critical for cardiac repair following infarction. Impaired angiogenesis in the infarcted heart can lead to rupture and immature/weakened scar tissue; therefore, factors regulating cardiac angiogenesis have drawn considerable attention. In this study, we determined the importance of ROS in cardiac angiogenesis following MI.

Firstly, we addressed the temporal and spatial changes of oxidative stress in the infarcted heart. Generally, oxidative stress is most evident in the early stage of repair after acute tissue damage; thus, the current study focused on the appearance of cardiac oxidative stress in the first two weeks post-MI. Oxidative stress is enhanced by an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidant reserve. Accordingly, we detected O−-producing NADPH oxidase and SOD expression in the infarcted heart. NADPH oxidase is an enzyme that catalyses the production of O− from oxygen and NADPH. It is a complex enzyme consisting of two membrane-bound components and three components in the cytosol, plus rac 1 or rac 2 (Lambeth 2004). Gp91phox is a membrane component of NADPH oxidase. In the current study, we observed markedly increased gp91phox expression, firstly in the border zone, followed by the infarcted myocardium, which peaked at day 7 and declined thereafter. Cells responsible for gp91phox production are primarily macrophages, indicating that these cells are a major source of ROS production in the infarcted myocardium. Studies from other laboratories have further demonstrated that other subunits of NADPH oxidase, such as p22phox, are also elevated in the infarcted myocardium (Fukui et al. 2001). These findings suggest that cardiac O− generation is enhanced in the early stage of MI.

The SOD is a class of enzymes that catalyse the dismutation of superoxide into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. There are three major families of SOD, depending on the presence of the metal cofactor: Cu/Zn (which binds both copper and zinc), Fe and Mn types (which bind either iron or manganese) and finally the Ni type (which binds nickel). Cu/Zn-SOD is located in the cytoplasm, Mn-SOD in the mitochondria and Ni-SOD is extracellular. Our study shows the evidence of a decrease in Cu/Zn-SOD and Mn-SOD in the rat infarcted myocardium, indicating impaired cardiac antioxidant reserve. It has been reported that other antioxidant enzymes are also reduced in the infarcted heart. Singal and colleagues have shown attenuated catalase activity in the rat infarcted myocardium (Hill & Singal 1997). Cardiac glutathione levels are also suppressed following MI (Usal et al. 1996). These observations indicate that both elevated ROS production and impaired antioxidant capacity may contribute to enhanced ROS levels in the infarcted myocardium. However, these changes are not observed in the non-infarcted myocardium, suggesting that oxidative stress is not evident in non-infarcted myocardium in the early stage of MI.

The development of oxidative stress in the infarcted myocardium is further confirmed by the markers of oxidative stress. MDA is a product of lipid oxidation (Papalambros et al. 2007) and serves as a marker of tissue oxidative stress. The current study shows that cardiac MDA level is significantly elevated in the infarcted myocardium at day 7 post-MI. The observation further supports the occurrence of oxidative stress in the infarcted myocardium.

Secondly, we detected temporal response of angiogenesis in the infarcted myocardium. Angiogenesis is a tightly regulated process. In the physiological condition, the activity of inducers and inhibitors of angiogenesis maintains a balance. Angiogenesis is activated in some pathological situations, such as cancer, diabetic retinopathy, rheumatoid arthritis, tissue repair and inflammatory diseases. Following acute MI, myocytes/interstitial cells and existing blood vessels in the infarcted myocardium undergo necrosis. Inflammatory cells infiltrate into the infarct myocardium and release angiogenic promoters, triggering cardiac repair and angiogenesis. Our study has shown that in rat experimental MI, angiogenesis was most evident in the infarcted myocardium at day 7 post-MI. Newly formed vessels were seen first in the border zones, which then extended into the infarcted myocardium. Microvascular density subsequently declined at day 14. These findings suggest that angiogenesis is most active in the inflammatory stage of cardiac repair following MI and that it is temporally and spatially coincident with cardiac oxidative stress.

Thirdly, we detected the potential regulation of ROS in angiogenesis in the infarcted heart. ROS have emerged as important in many pathophysiological processes. Their effects can be beneficial or deleterious at the site of production. In addition to their well-known damaging effects, ROS also have signalling roles, acting as second messengers that modulate the activity of diverse intracellular signalling pathways and transcription factors. ROS may influence signal transduction pathways through changes in the activity of redox-sensitive protein kinases; through altering the activity of redox-sensitive transcription factors and/or through direct effects on enzymes or receptors (Griendling 2004; Li & Shah 2004; Frey et al. 2006). In the current study, we observed co-localized oxidative stress and angiogenesis in the infarcted heart. Moreover, we found that antioxidant treatment significantly suppressed microvascular density in the infarcted myocardium. These observations suggest that ROS promote angiogenesis and are involved in cardiac repair following MI.

However, the mechanisms responsible for ROS-mediated angiogenesis remain to be elucidated. It has been reported that NADPH oxidase-derived ROS stimulate the expression of adhesion molecules, cytokines and MMPs, which act through the activation of MAPKs and/or NF-kB. Hence, ROS may promote cardiac angiogenesis by (i) stimulating MMP activity and angiogenic integrins, which leads to the degradation of basement membrane and promotes endothelial cells to migrate into the infarcted myocardium; (ii) activating angiogenic inducers, such as VEGF and FGF, thereby promoting endothelial cell proliferation and tube formation and (iii) activating redox-sensitive nuclear factor (NF-kappaB). Further studies are required to test these hypotheses.

The ROS have both beneficial and deleterious effects on the infarcted heart. Oxidative stress is mostly evident in the infarcted myocardium in the early stage of MI and develops later on in non-infarcted myocardium. ROS stimulate angiogenesis and facilitate cardiac repair in the infarcted myocardium in the early stage of MI. However, ROS promote cardiac remodelling, including hypertrophy, apoptosis and interstitial fibrosis, in non-infarcted myocardium and contribute to cardiac dysfunction in the late stage of MI (Looi et al. 2008). Thus, inhibition of ROS in the early phase of MI may impair angiogenesis in the infarcted myocardium, whereas antioxidant treatment given after one week post-MI should be protective against ventricular remodelling.

In summary, following acute MI, oxidative stress and angiogenesis are temporally and spatially coincident in the infarcted myocardium. Antioxidant treatment suppresses angiogenesis at the site of MI. These findings suggest that ROS promote formation of new vessels in the infarcted heart and contribute to cardiac repair. The mechanisms responsible for ROS-mediated angiogenesis remain to be determined.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute (RO1-HL77668, Yao Sun).

References

- Abid MR, Kachra Z, Spokes KC, Aird WC. NADPH oxidase activity is required for endothelial cell proliferation and migration. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:252–256. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai T, Fassina G, Morini M, et al. N-acetylcysteine inhibits endothelial cell invasion and angiogenesis. Lab. Invest. 1999;79:1151–1159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway EM, Collen D, Carmeliet P. Molecular mechanisms of blood vessel growth. Cardiovasc. Res. 2001;49:507–521. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00281-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworakowski R, Anilkumar N, Zhang M, Shah AM. Redox signalling involving NADPH oxidase-derived reactive oxygen species. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2006;34:960–964. doi: 10.1042/BST0340960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey RS, Gao X, Javaid K, Siddiqui SS, Rahman A, Malik AB. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase gamma signaling through protein kinase Czeta induces NADPH oxidase-mediated oxidant generation and NF-kappaB activation in endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:16128–16138. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508810200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui T, Yoshiyama M, Hanatani A, Omura T, Yoshikawa J, Abe Y. Expression of p22-phox and gp91-phox, essential components of NADPH oxidase, increases after myocardial infarction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;281:1200–1206. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.4493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griendling KK. Novel NAD(P)H oxidases in the cardiovascular system. Heart. 2004;90:491–493. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.029397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu W, Weihrauch D, Tanaka K, et al. Reactive oxygen species are critical mediators of coronary collateral development in a canine model. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2003;285:H1582–H1589. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00318.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MF, Singal PK. Right and left myocardial antioxidant responses during heart failure subsequent to myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1997;96:2414–2420. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang DH, Kanellis J, Hugo C, et al. Role of the microvascular endothelium in progressive renal disease. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2002;13:806–816. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V133806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambeth JD. NOX enzymes and the biology of reactive oxygen. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2004;4:181–189. doi: 10.1038/nri1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li JM, Shah AM. Endothelial cell superoxide generation: regulation and relevance for cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004;287:R1014–R1030. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00124.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Looi YH, Grieve DJ, Siva A, et al. Involvement of Nox2 NADPH oxidase in adverse cardiac remodeling after myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2008;51:319–325. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.101980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Chen SS, Zhang JQ, Ramires FJ, Sun Y. Activation of nuclear factor-kappaB and its proinflammatory mediator cascade in the infarcted rat heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;321:879–885. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maulik N, Das DK. Redox signaling in vascular angiogenesis. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002;33:1047–1060. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)01005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papalambros E, Sigala F, Georgopoulos S, et al. Malondialdehyde as an indicator of oxidative stress during abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. Angiology. 2007;58:477–482. doi: 10.1177/0003319707305246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Dewald O, Frangogiannis NG. Inflammatory mechanisms in myocardial infarction. Curr. Drug Targets Inflamm. Allergy. 2003;2:242–256. doi: 10.2174/1568010033484098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruef J, Hu ZY, Yin LY, et al. Induction of vascular endothelial growth factor in balloon-injured baboon arteries. A novel role for reactive oxygen species in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 1997;81:24–33. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoszuk M, Leonor L, Espinoza F, Carpenter PM, Nalcioglu O, Su MY. Measuring microvascular density in tumors by digital dissection. Anal. Quant. Cytol. Histol. 2002;24:15–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selektor Y, Ahokas RA, Bhattacharya SK, Sun Y, Gerling IC, Weber KT. Cinacalcet and the prevention of secondary hyperparathyroidism in rats with aldosteronism. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2008;335:105–110. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e318134f013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shono T, Ono M, Izumi H, et al. Involvement of the transcription factor NF-kappaB in tubular morphogenesis of human microvascular endothelial cells by oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:4231–4239. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timar J, Dome B, Fazekas K, Janovics A, Paku S. Angiogenesis-dependent diseases and angiogenesis therapy. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 2001;7:85–94. doi: 10.1007/BF03032573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usal A, Acarturk E, Yuregir GT, et al. Decreased glutathione levels in acute myocardial infarction. Jpn. Heart J. 1996;37:177–182. doi: 10.1536/ihj.37.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda M, Ohzeki Y, Shimizu S, et al. Stimulation of in vitro angiogenesis by hydrogen peroxide and the relation with ETS-1 in endothelial cells. Life Sci. 1999;64:249–258. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00560-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young IS, Woodside JV. Antioxidants in health and disease. J. Clin. Pathol. 2001;54:176–186. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.3.176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Lu L, Chen SS, Sun Y. Temporal and spatial characteristics of apoptosis in the infarcted rat heart. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;325:605–611. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.10.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao W, Chen SS, Chen Y, Ahokas RA, Sun Y. Kidney fibrosis in hypertensive rats: role of oxidative stress. Am. J. Nephrol. 2008;28:548–554. doi: 10.1159/000115289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]