Abstract

Numerous studies demonstrate inflammatory proteins in the brain and microcirculation in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and implicate inflammation in disease pathogenesis. However, emerging literature suggests that neuroinflammation can also be neuroprotective. The chemokine RANTES has been implicated in neurodegenerative diseases including AD. The objectives of this study are to determine the expression of RANTES in AD microvessels, its regulation in endothelial cells and its effects on neuronal survival. Our data show elevated expression of RANTES in the cerebral microcirculation of AD patients. Treatment of neurons in vitro with RANTES results in an increase in cell survival and a neuroprotective effect against the toxicity of thrombin and sodium nitroprusside. Oxidative stress upregulates RANTES expression in rat brain endothelial cells. Developing strategies to augment neuroprotection and diminish inflammatory activation of multifunctional mediators such as RANTES holds promise for the development of novel neuroprotective therapeutics in AD.

Keywords: RANTES, inflammation, neurotoxicity, endothelial cells, oxidative stress, neuroprotection

1. Introduction

Numerous studies demonstrate the presence of inflammatory proteins and implicate pro-inflammatory mechanisms in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [20,27,28,35]. Our laboratory has previously shown that in the AD brain the microcirculation is a rich source of inflammatory proteins such as interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), and macrophage inflammatory protein-1 (MIP-1α) [16,17,43,44]. Chemokines, such as the CC chemokine RANTES (regulated on activation, normal T-cell expressed and secreted), and their G protein-coupled receptors, are found on endothelial cells, glia and neurons throughout the brain, suggesting important functions for this inflammatory superfamily in the CNS [33]. In this regard, a recent study using cDNA microarrays documents a large number of RANTES-responsive genes in cultured neurons that appear to be involved in neuronal survival and differentiation [46].

RANTES and its receptor CCR5 have been implicated in a wide array of pathological conditions in the brain and neurodegenerative diseases. Neurodegenerative disorders that involve neuroinflammation such as multiple sclerosis, stroke, AD, Parkinson’s disease (PD) and HIV-associated dementia are associated with local upregulation and release of chemokines [5,12,48]. The amyloid beta protein, a characteristic feature of AD pathology, induces chemokine expression when injected into the hippocampus [22]. Despite these associations, the role of RANTES in the diseased CNS is unclear because in addition to its established role in leukocyte recruitment and activation, RANTES has recently been shown to protect mixed cultures of human neurons and astrocytes from HIV-tat or NMDA-induced apoptosis [10]. Accumulating evidence suggests that although inflammatory proteins in the CNS are usually considered detrimental, they can also be beneficial and have neuroprotective effects [23,29,42]. Expression of RANTES could have important implications for neuronal function in health and disease. Little is known about the regulation of RANTES in the brain under physiological or pathological conditions. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have been shown to cause an increase in RANTES expression during viral infection [26]. In astrocytes, several chemokines, including RANTES, are upregulated in response to a cytokine-mediated increase in ROS [37]. Also, in the periphery, oxidized lipids regulate RANTES expression [3]. In the AD brain there is an increase in oxidative stress and inflammatory proteins and cross-talk between both of these types of biomediators [32]. We have shown that brain AD-derived microvessels express high levels of MIP-1α compared to brain microvessels isolated from controls [45]. Treatment of brain endothelial cell cultures with menadione, a superoxide releasing compound, hydrogen peroxide, lipopolysacharride, or oxidatively modified low density lipoproteins results in a dose- dependent increase in MIP-1α mRNA levels and MIP-1α release into the media [45]. Taken together, these data implicate ROS in the regulation of RANTES in the CNS.

The objectives of this study are to determine the expression of RANTES in AD microvessels, its regulation in brain endothelial cells by oxidative stress and the effects of this chemokine on neuronal survival.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Brain endothelial cell cultures

Rat brain endothelial cells were obtained from rat brain microvessels, as previously described [8,45]. The purity of the endothelial cultures was confirmed using antibodies to endothelial cell surface antigen Factor VIII. Endothelial cells used in this study (passages 8 to 12) were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% glutamine and 1% antibiotics in a humidified 5% CO2, 95% O2 air incubator at 37ºC.

2.2 Human brain microvessel isolation

Human brain microvessels were isolated from human autopsy brains with an average postmortem time of 10–16 h. Right cerebral hemispheres from control and AD patients were stored at −70°C and used for the experiments described herein. Left cerebral hemispheres were histologically processed for diagnostic and morphometric studies for the clinical diagnosis of primary degenerative AD dementia. Each case was examined for neuritic plaques and neurofilbrillary tangles as recommended by National Institutes of Health Neuropathology Panel and each case fulfilled the rigorous morphometric criteria of AD as stated in the Dementia Study Laboratory, University of Western Ontario AD [2,24]. Control samples from age-matched patients without evidence of neuropathology and similar post-mortem intervals were also collected. Seven control and seven AD aged matched brains were used for this study. Microvessels were isolated from pooled temporal, parietal, and frontal cortices, as we have previously described [15]. The cortices were placed in cold Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS), scissor minced, and homogenized. After centrifugation (3000 g) for 15 min at 4ºC, the supernatant was discarded and the pellet resuspended in cold HBSS containing 15% dextran and 5% FBS. The suspension was then centrifuged at 5500 g for 20 min at 4ºC. The pellet was resupended in HBSS and filtered through a 53 μm nylon mesh sieve. Microvessels on the mesh were resupended in DMEM containing 10% FBS and dimethyl sulfoxide and stored frozen in liquid nitrogen. About 6 to 10 mg microvessel protein from 15 g human cortex were obtained.

2.3 Oxidative modification of LDL

LDL was modified using hydroxynonenal (HNE) and copper sulfate. LDL was modified by incubating with 1 mM HNE for 24 h at 37ºC in PBS or 5 μM copper sulfate at 37ºC for 4 h in PBS, as previously described [19,45]. The reaction was stopped with 100 μM butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT). The modified LDLs were dialyzed extensively against PBS at 4ºC to remove salts. Modified LDL samples were electrophoresed on 4 to 15% gradient SDS-PAGE and stained with coomasie. Modification of LDL was determined with thiobarbituric acid-reactive substance (TBARS). LDL, HNE-LDL and oxidized LDL were incubated with thiobarbituric acid solution (0.37% w/v thiobarbituric acid, 15% w/v trichloroacetic acid in 0.25 N HCL) for 30 min at 95 ºC. After centrifugation, the supernatant was removed, and the absorbance determined at 535 nm. Tetramethoxypropane was used as a standard which yields malondialdehyde (MDA) with acid treatment. Extent of oxidation (TBARS level) was expressed as a measure MDA per mg of protein (nM MDA/mg protein). Oxidation of both HNE-LDL (32.4 ± 1.6 nM MDA/mg protein) and Ox-LDL (52.5 ± 3.1 nM MDA/mg protein) was significantly (p<0.001) higher than LDL alone (17.1 ± 0.8 nM MDA/mg protein).

2.4 Treatment of endothelial cell and cerebral cortical cell cultures

Rat brain endothelial cells (passage 8 to 12) were grown to 85% confluence, rinsed with serum-free DMEM and then incubated in serum-free DMEM plus endothelial cell growth supplement (3 μg/ml). Cells were treated with either menadione (0.5 – 50 μM) for 1 h, H2O2 (1 – 500 μM) for 4 h, lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (1 – 500 ng/ml) for 4 h, or oxidatively modified LDLs (10 μg/ml) for 24 h.

Rat cerebral cortical cultures (CCC) were prepared from cortices isolated from 18 day gestation rat fetuses as previously described [15]. The cells were then seeded at a density of 3–5 × 105 cells per ml on 6-well poly-L-lysine coated plates. The medium was changed at day 2 to Neurobasal medium containing B-27 supplement, antibiotic/antimycotic, glutamine (0.5 mM) and 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine (20 μg/ml) to inhibit proliferation of glial cells. On day 5, fresh medium without 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine was added. Neuronal cultures were used for experiments after 8–9 days in culture.

At 8 days after culture, media on neuron cells were changed to Neurobasal medium containing N2 supplement, antibiotic/antimycotic and 0.5 mM glutamine. Cells were then incubated with or without RANTES (25, 50, 100, 300 and 500 ng/ml) for 24 h.

2.5 RT-PCR analysis of RANTES mRNA

Total RNA was extracted from the treated endothelial cells using the Trizol method (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and then DNase treated using the ZymoResearch kit according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using random primers (Roche Applied Science) and amplified by PCR (5 min-95ºC, 40 cycles of 45 sec- 94º C and 1 min-60 º C) using a Mastercycler system (Eppendorf). The number of cycles used was optimized for each experiment and the samples were measured (40 cycles) in the linear phase of amplification. PCR reactions for the specific primers were performed for the triplicate set of experiments. Primers used for PCR are shown in Table 1. The PCR products were visualized on a 1.5% agarose gel using UV trans-illumination.

Table 1.

Primers

| Gene | Orientation | Sequence | Amplicon |

|---|---|---|---|

| β-Actin | Left primer Right primer |

GTCACCAACTGGGACGATA TCTCAGCTGTGGTGGTGAAG |

380 bp |

| RANTES (Rat) | Left primer Right primer |

ATATGGCTCGGACACCACTC AGCCTGTGAAGAGCACACCT |

389 bp |

| RANTES (Human) | Left Primer Right Primer |

AGCTACTCGGGAGGCTAAGG GCCAGTAAGCTCCTGTGAGG |

349 bp |

| GAPDH | Left Primer Right Primer |

CCATGGAGAAGGCTGGGG CAAAGTTGTCATGGATGACC |

194 bp |

2.6 Measurement of cell survival by MTT assay

After treatment with various agents, cells were incubated with the MTT reagent 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide. This tetrazolium salt converts to formazon which is quantified by colorimetric assay (Cell Titer 96 One Aqueous solution cell proliferation assay, Promega, Madison, WI). Cells were incubated with the MTT reagent (1:40 dilution) for 10 min at 37°C. The formazon product was read at 490 nm. In each experiment, the number of control cells i.e. viable cells not exposed to any treatment was defined at 100%.

2.7 Detection of RANTES by ELISA

Indirect ELISA was used to detect RANTES released in the supernatant.

Protein samples were coated in 96-well immulon 2HB (Fisher scientific) flat bottom plates with sodium bicarbonate buffer (0.1 M) and incubated overnight at 4 °C. The plates were blocked by 1% bovine serum albumin solution and incubated at 37°C for 45 min. After washing two times, 200 μl of primary antibodies (RANTES - ab 9783 (rat); ab 7314 (human); AbCam, Cambridge, MA) diluted (1:1000) in carbamate buffer were added and incubated overnight at 4°C. Extensive washing of the plate to remove unbound antibody was followed by the addition of 200 μl of rabbit anti-goat IgG coupled with horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA 1/1,000 dilution) and incubated for 45 min at 37°C, in the dark. The reaction was developed by adding 200 μl/well of o-phenylene diamine H2O2 (Pierce, Chemicon, CA, USA) for 20 min. Optical density was measured at 450 nm using a microplate ELISA reader (BIO-RAD). Samples were assayed in triplicate.

2.8 Statistical analysis

Data from each experiment are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Two-tailed Student’s t test was performed between AD and control samples. The one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests for multiple samples. Statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

3. Results

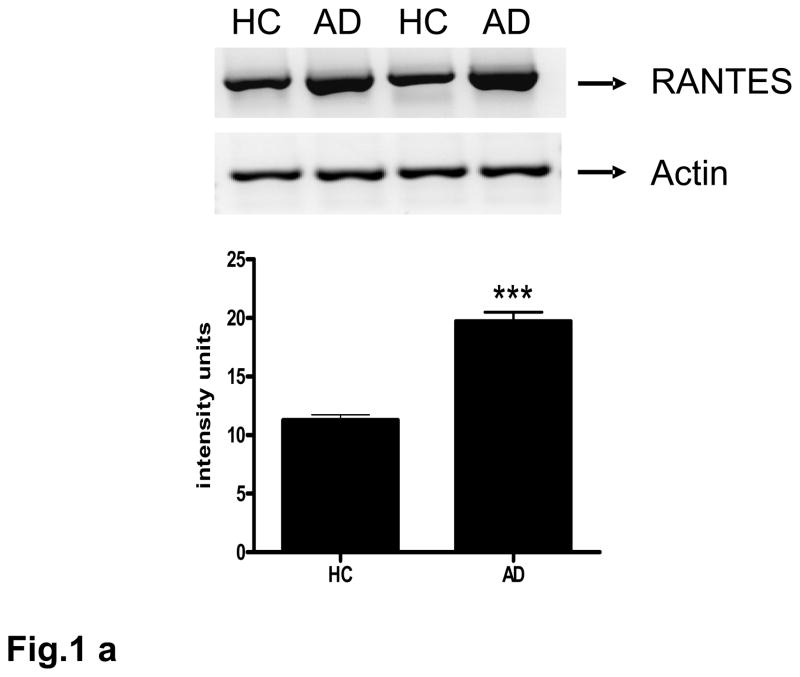

3.1 RANTES is expressed and released in AD-derived microvessel

Expression of the RANTES transcript in AD-derived brain microvessels was evaluated by RT-PCR. A strong 349 bp band corresponding to RANTES in brain microvessels was detected in both control and AD-derived samples (Fig. 1a). Expression of RANTES in AD-derived microvessels was significantly (p<0.001) higher than that found in control-derived vessels.

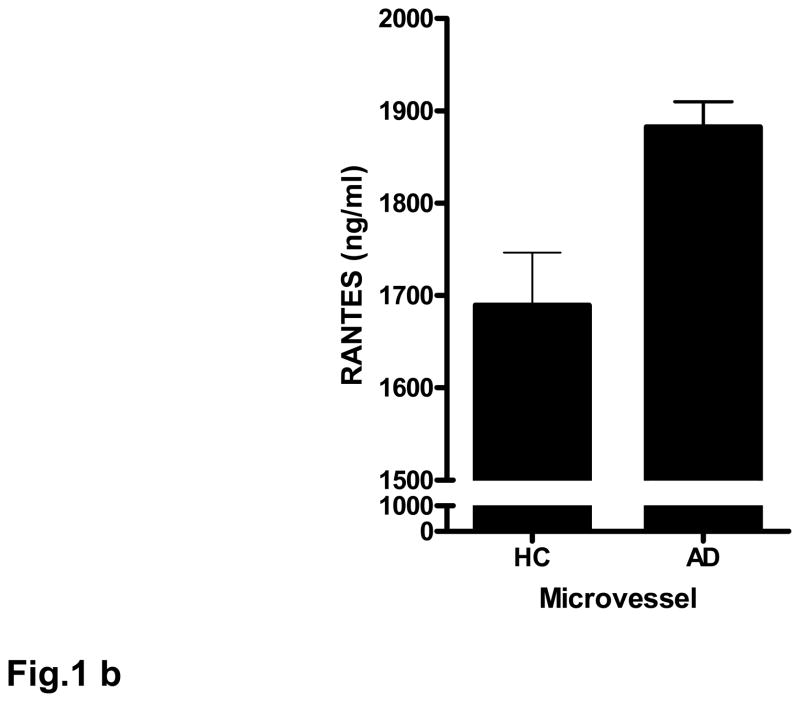

Fig. 1. AD-derived microvessels express and release high levels of RANTES.

(a) Total RNA from brain microvessel from AD-derived (AD) and age matched controls (HC) were reverse transcribed and amplified using specific primers for RANTES. Data are normalized relative to GAPDH expression. Bar graph represents data from 7 AD samples and 7 control samples; ***p<0.001 vs. control. (b) Control (HC) and AD-derived microvessels (50 μg) were incubated in serum-free media supplemented with 1% LAH for 4 h. Microvessels were centrifuged and the supernatant analyzed by ELISA. Data are mean ± SD from 5 AD and 5 control patient samples performed in quadruplicate. The data are normalized to samples containing 1% LAH; *p<0.05 vs. control.

The release of RANTES from microvessels incubated in serum-free media supplemented with 1 % lactalbumin hydrolysate (LAH) for 4 h was quantified by ELISA. In a pattern similar to data obtained by RT-PCR, both AD-derived and age-matched control vessels released RANTES (Fig. 1b), but release was significantly (p<0.05) higher in AD-derived vessels compared to controls.

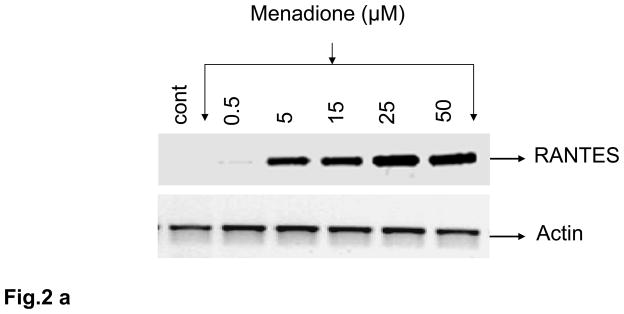

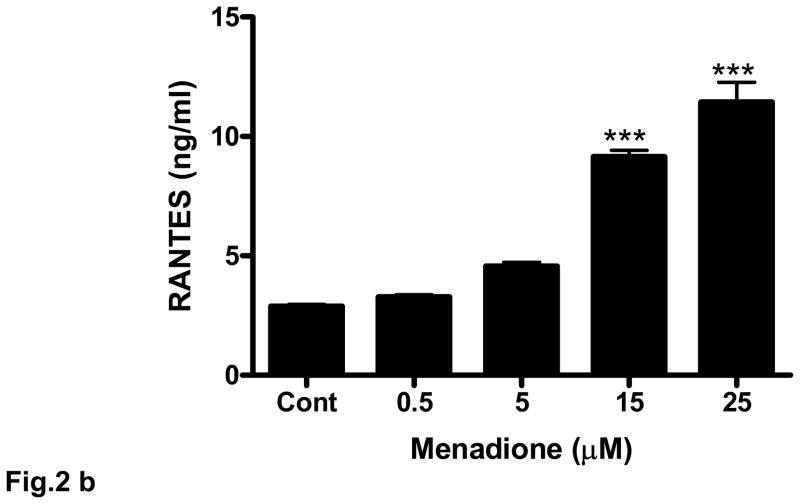

3.2 Induction of RANTES by oxidative stress in cultured rat brain endothelial cells

Oxidative stress was induced in rat brain endothelial cells using either menadione (0.5 – 50 μM) for 4 h at 37°C. Menadione causes oxidative stress in vitro by releasing ROS including superoxide and hydrogen peroxide [36]. Menadione caused a dose-dependent increase the expression of RANTES mRNA (Fig. 2a). The increase in RANTES expression was strongly evident at 5 μM and maximal at 25 μM. Also, incubation of rat brain endothelial cells with menadione caused release of RANTES protein into the supernatant. ELISA measurement of RANTES indicated a significant (p<0.001) increase in RANTES release at 15 μM menadione, with maximal chemokine release evoked by 25 μM menadione (Fig. 2b).

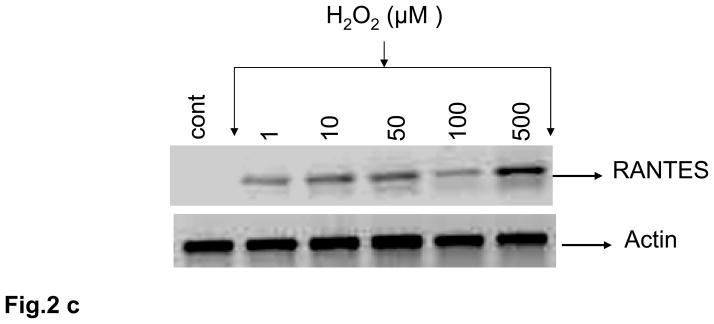

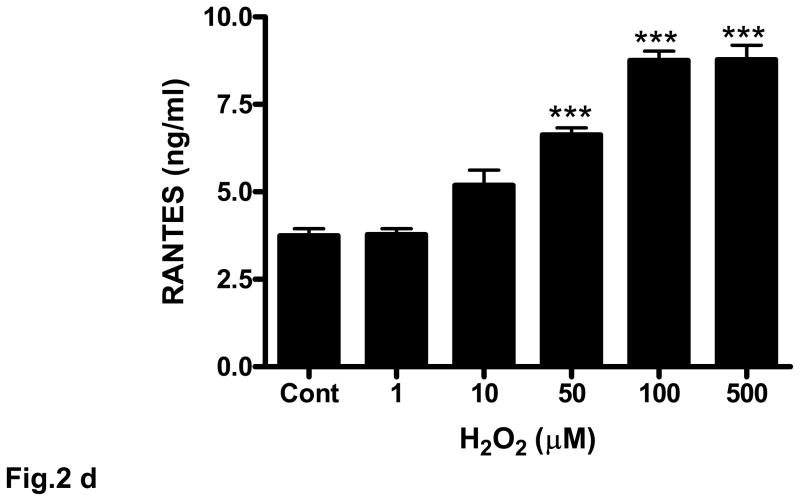

Fig. 2. Oxidative stress stimulates RANTES expression and release.

(a) Rat brain endothelial cells were incubated with menadione (0.5 – 50 μM). Total RNA extracted was reverse-transcribed and amplified with RANTES primers. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. (b) Rat brain endothelial cells were incubated with menadione (0.5 – 25 μM) and RANTES released into the supernatant quantified by ELISA; ***p<0.001 vs control. (c) Rat brain endothelial cells were incubated with H2O2 (1 – 500 μM). Total RNA extracted was reverse-transcribed and amplified with RANTES primers. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. (d) Rat brain endothelial cells were incubated with H2O2 (1 – 500 μM) and RANTES released into the supernatant quantified by ELISA; ***p<0.001 vs. control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Although menadione can release H2O2, we also evaluated the direct effect of H2O2 on expression and release of RANTES from cultured rat brain endothelial cells. Incubation of endothelial cells with 1 μM H2O2 evoked demonstrable expression of RANTES that was maximal at 500 μM (Fig. 2c). Release of RANTES into the supernatant of cultured cells in response to H2O2 was more clearly dose-dependent over the range examined (1 – 500 μM) with concentrations of 50 μM or higher resulting in significant (p<0.001) release of RANTES protein compared to untreated cells (Fig. 2d).

3.3 LPS induces RANTES expression in cultured rat brain endothelial cells

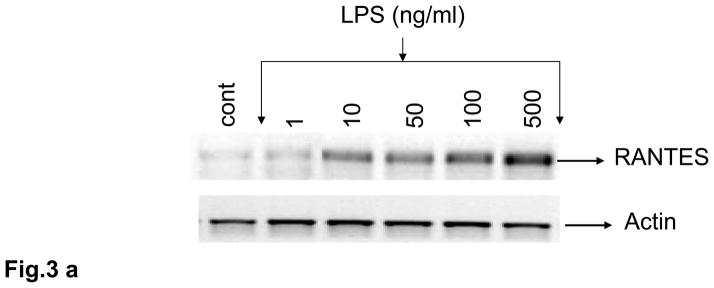

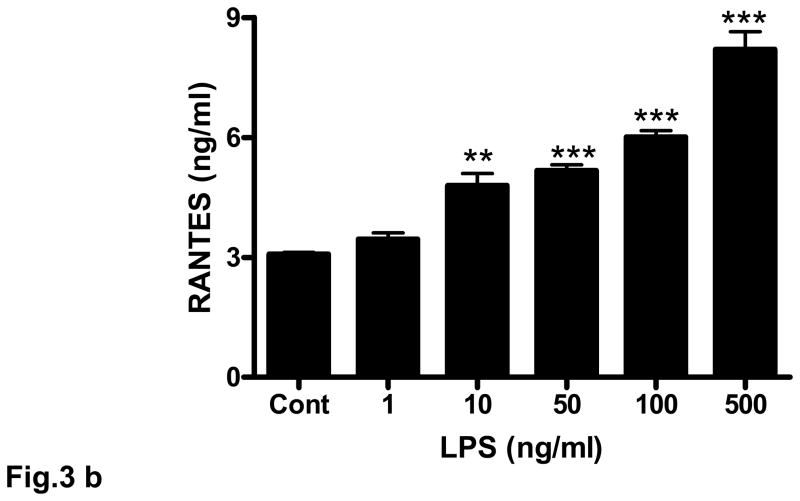

Rat brain endothelial cells were incubated with LPS (1 – 500 ng/ml) for 4 h. Induction of RANTES mRNA was evaluated by RT-PCR. Similar to the effect shown for H2O2, LPS evoked demonstrable expression of RANTES at 10 – 100 ng/ml (Fig. 3a). However, addition of 500 ng/ml of LPS caused a large induction of RANTES mRNA (Fig. 3a). Release of RANTES into the supernatant of cultured cells in response to LPS was more clearly dose-dependent over the range examined (1 – 500 ng/ml) with concentrations of 10 ng/ml (p<0.01) and 50 ng/ml (p<0.001) or higher resulting in high levels of RANTES released compared to untreated cells (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. LPS increases expression and release of RANTES in rat cultured brain endothelial cells.

Cultured rat brain endothelial cells were grown to 85% confluent and treated with LPS (1 –500 ng) for 4 h. (a) Total RNA extracted was reverse-transcribed and amplified with RANTES primers. Data are representative of 3 separate experiments. (b) Release of RANTES into culture supernatant was quantified by ELISA; **p<0.01 vs control; ***p<0.001 vs control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

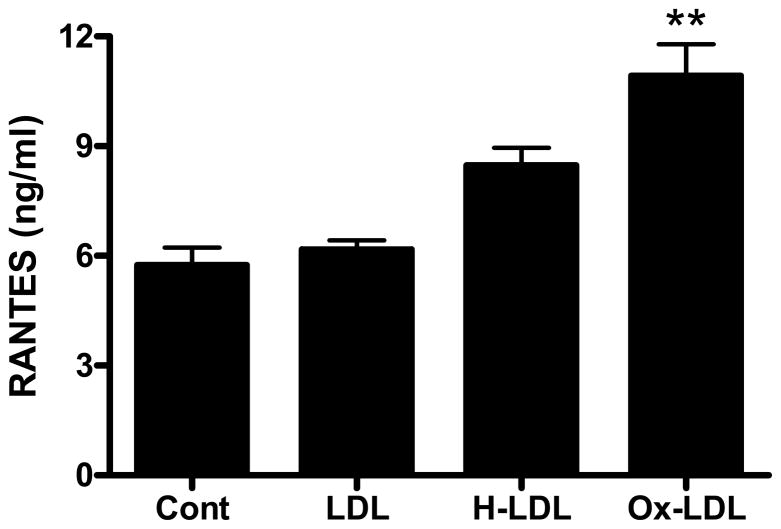

3.4 Oxidized LDL stimulates release of RANTES from rat brain endothelial cells

LDL was oxidized with copper sulfate (Ox-LDL) or HNE (HNE-LDL). Treatment of rat brain endothelial cells with HNE-LDL resulted in a small increase in RANTES release (Fig. 4). Exposure of rat brain endothelial cells to a more highly oxidized form of LDL (Ox-LDL) caused a significant (p<0.01) increase in RANTES release (Fig 4).

Fig. 4. Oxidatively modified LDLs stimulate the expression of RANTES in rat endothelial cells.

LDL was modified with copper sulfate or HNE. Rat brain endothelial cells were treated with 10 μg/ml LDL, Ox-LDL or HNE-LDL for 24 h. RANTES released into the supernatant was determined by ELISA. Data are mean ± SD values for 3 separate experiments; **p<0.01 vs. LDL. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

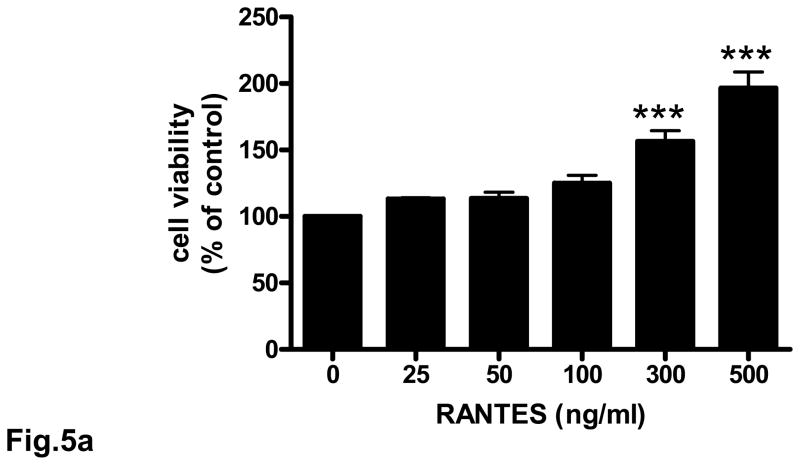

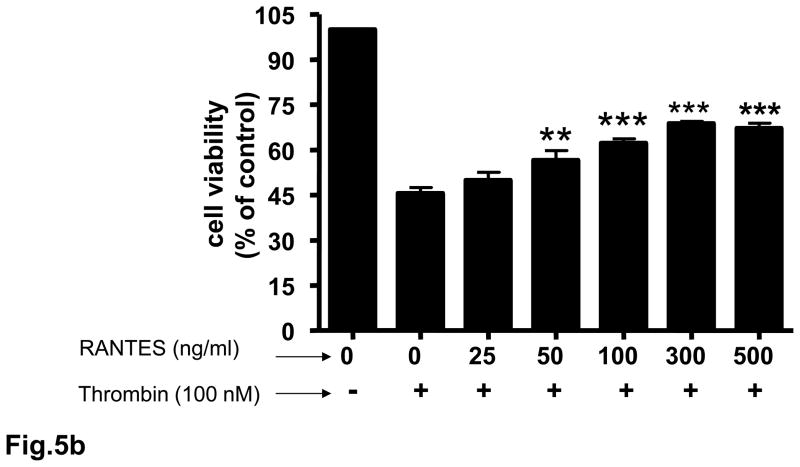

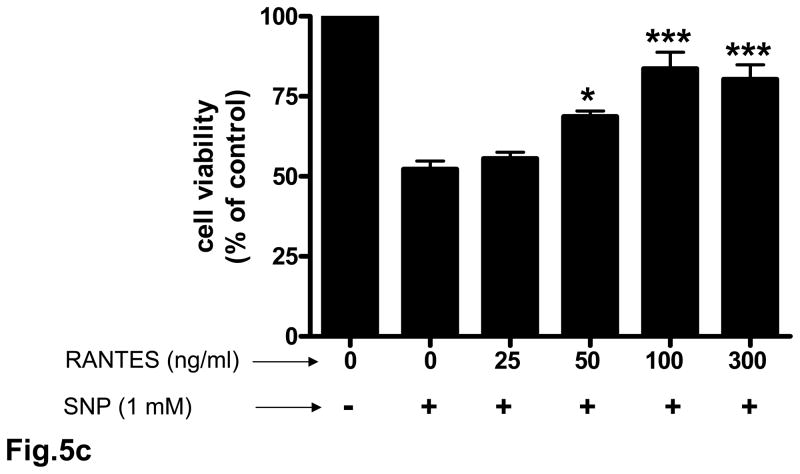

3.5. Neuroprotective effect of RANTES on cerebral cortical cultures

Rat cortical cell cultures were incubated with 0 – 500 ng/ml RANTES for 24 h and cell survival assessed. Treatment of neuronal cultures with RANTES resulted in a significant (p<0.001) increase in cell survival compared to untreated cells (Fig. 5a). RANTES also exerted a neuroprotective effect against the toxicity of thrombin and sodium nitroprusside (SNP) (Figs. 5b and 5c). In cells pretreated for 24 h with RANTES the neurotoxic effect of thrombin (100 nM) was significantly (p<0.01 – p<0.001) reduced (Fig. 5b). Similarly, pretreatment of cultured neurons with RANTES significantly (p<0.05 – p<0.001) reduced cell death when challenged with 1 mM SNP (Fig. 5c).

Fig. 5. Neuroprotective effect of RANTES on cerebral cortical cultures.

Rat cortical cultures were incubated with or without RANTES (25 – 500 ng/ml) for 24 h. Cell viability was determined with the MTT assay. The number of viable cells without any RANTES treatment (control) were defined as 100 %. (a) Pretreatment with RANTES resulted in significant (p<0.001) cell survival compared to cells incubated without RANTES. (b) Rat cortical cultures pretreated with RANTES (25 – 500 ng/ml) for 24 h were incubated with 100 nM of thrombin for 18 h and cell viability determined; **p<0.01 vs control; ***p<0.001 vs control. (c) Rat cortical cultures pretreated with RANTES (25 – 500 ng/ml) for 24 h were incubated with 1 mM SNP for 4 h and cell viability determined; *p<0.05 vs control; ***p<0.001 vs control. Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

4. Discussion

In the current study we document elevated expression of RANTES in the cerebral microcirculation of AD patients. This result is consistent with data that show increases in inflammatory proteins, both cytokines and chemokines, in the AD brain and microcirculation. However, the interpretation of these findings in the context of disease pathogenesis is complex.

A large number of inflammatory mediators have been identified in the AD brain [27,28]. Epidemiologic and laboratory studies suggest that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAIDs) use reduces the risk of AD or delays disease onset [4]. Despite these data, randomized clinical trials using NSAIDs have been unsuccessful at preventing disease, suggesting that the functions of inflammation in the AD brain are multifaceted. Emerging literature suggests that neuroinflammation in the AD brain is a double-edged sword and that inflammatory reactions in the CNS can contribute to neuroprotection as well as neurotoxicity. For example, TNF-α which is elevated in AD and initially described as an inducer of cell death, can protect neurons from the effects of several neurotoxic agents and has been shown to reduce tau hyperphosphorylation [29]. Whether inflammation is neurotoxic or neuroprotective may depend on the context, location and timing of inflammatory mediators. TNF-α and IL-1β exert neurotoxicity in cerebral ischemia in the presence of elevated inducible NO synthase (iNOS) while in the absence of iNOS, both cytokines appear to contribute to neuroprotection and plasticity, highlighting the role of context [39]. Location of the inflammatory mediator in relation to an injury could also determine a neuroprotective/neurotoxic response. TNF-α upregulated in the proximity of an evolving lesion contributes to secondary infarct growth whereas cytokine induction remote from the ischemic lesion confers neuroprotection [40]. Finally, the timing of the inflammatory response may determine outcome. In a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease (PD), delivery of a pro-inflammatory protein prior to administration of the neurotoxin 6-hydroxydopamine reduces neuronal cell loss [1].

Elevated levels of RANTES and its CCR5 receptor are found in the brain in injury and disease states including, trauma, prion disease, cerebral malaria, HIV-dementia, PD and AD [11,13,18,25,34,48]. Also, exposure of astrocytes to the amyloid-β peptide results in increased levels of RANTES [22]. However, the functional significance of this elevated expression is unclear.

RANTES has been indirectly implicated as mediator of neuronal injury in several studies. Increases in RANTES coincide with increased neuronal death in a brain injury model. Infection by Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) causes upregulation of RANTES gene expression that, although not directly responsible for JEV-induced neuronal death, contributes to recruitment of immune cells to the neurodegenerative process [6]. In AD, chemokines and their receptors are found associated with AD lesions [48]. On the other hand, several studies including the present have shown a neuroprotective effect for chemokines. Ablation of the receptor for the chemokine fractalkine exacerbates neuronal loss in mouse models of PD and ALS [31]. The chemokine receptor CCR2 is protective against noise-induced hair cell death [36]. Both RANTES and MCP-1 protect mixed cultures of human neurons and astrocytes from HIV-tat or NMDA-induced apoptosis [10]. In the current paper we report that treatment of primary cortical neuronal cultures with RANTES enhances neuronal survival. Furthermore, we document that exposure of neuronal cultures to RANTES before treatment with a neurotoxic agent causes a significant reduction in neuronal cell death. The ability of RANTES to decrease neuronal cell death in response to both thrombin and SNP could be relevant for AD, as both thrombin and nitric oxide (the active species released from SNP) are neurotoxic and elevated in the AD brain and microcirculation [9,17].

How RANTES exerts its neuroprotective effects is unclear. A recent study has shown that RANTES can signal via the orphan G protein-coupled receptor GPR75 [21]. Signaling through this receptor has been shown to be neuroprotective in a hippocampal cell line following insult with the neurotoxic amyloid-beta peptide [21,30]. Also, recent studies have shown that the neuroprotective effects of PACAP38 are in part mediated by its release of RANTES from astrocytes [4,7].

Oxidized lipids as well as oxidant species evoked by viral infection has been shown to elevate RANTES in the periphery [3,26]. In the brain, cytokines, specifically TNF- α and IL-1β have been shown to increase release of RANTES and other chemokines from astrocytes. Flavonoids, anti-oxidant compounds, significantly decrease the release of ROS from astrocytes stimulated with IL-1β and result in a decrease in cytokine-stimulated RANTES release [37], highlighting the importance of oxidative species in RANTES regulation. The results of the current study add to this growing literature and document an increase in RANTES expression in rat brain endothelial cells after exposure to menadione, a superoxide releasing species as well as H2O2. Addition of oxidatively modified lipids (HNE-HDL, Ox-LDL) also increases RANTES expression in rat brain endothelial cells. The species with the highest level of oxidation evoked the largest increase in RANTES release. Our data support a model where both inflammatory proteins (cytokines, LPS) and oxidant species (O2−, H2O2) contribute to RANTES regulation in the brain.

The cerebral microcirculation could represent a pivotal locus for the convergence of oxidative stress and inflammatory processes in the AD brain. Endothelial cells could contribute to the neuronal microenvironment via both autocrine and paracrine mechanisms. For instance, cytokines (such as IL-1β and TNF-α) stimulate ROS production by rat brain endothelial cells. The ROS in turn stimulate these cells to release other cytokines (IL-6) and chemokines (RANTES) [47]. We have documented a dynamic role for the microcirculation as a source of soluble factors that affect neurons and other cells in the AD brain [14]. Understanding the regulation of multifunctional mediators and developing strategies to exploit the dual function of chemokines like RANTES, i.e. augmenting neuroprotection and diminishing inflammatory activation, holds promise for the development of novel neuroprotective therapeutics in AD.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support: This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG15964, AG020569 and AG028367), a grant from McNeil Consumer Healthcare Division of McNeil-PPC, Inc. Human tissue was kindly provided by Northwestern ADC Neuropathy Core at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Dr. Grammas is the recipient of the Shirley and Mildred Garrison Chair in Aging. The authors gratefully acknowledge the secretarial assistance of Terri Stahl.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

All authors have contributed to the work and agree with the presented findings. This work has not been published before nor is it being considered for publication by another journal. There are no actual or potential conflicts of interest with any of the authors.

Human samples were obtained, in accordance with institutional guidelines, from post-mortem material. Experiments utilizing animals were performed in strict compliance with NIH and Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee standards. This work was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AG15964, AG020569 and AG028367), a grant from McNeil Consumer Healthcare Division of McNeil-PPC, Inc. Human tissue was kindly provided by Northwestern ADC Neuropathy Core at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. Additional funding was provided by the Mildred and Shirley Garrison Endowed Chair in Aging.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Armentero MT, Levandis G, Nappi G, Bazzani E, Blandini F. Peripheral inflammation and neuroprotection: systemic pretreatment with complete Freund’s adjuvant reduces 6-hydroxydopamine toxicity in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;24:494–505. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2006.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball MJ, Griffin-brooks S, MacGregor JA, Ojalvo-Rose E, Fewster PH. Neuropathological definition of Alzheimer disease: multivariate analyses in the morphometric distinction between Alzheimer dementia and normal aging. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 1988;2:29–37. doi: 10.1097/00002093-198802010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barlic J, Murphy PM. Chemokine regulation of atherosclerosis. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:226–36. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1206761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenneman DE, Hauser JM, Spong C, Phillips TM. Chemokine release is associated with the protective action of PACAP38-38 against HIV envelope protein neurotoxicity. Neuropeptides. 2002;36:271–80. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4179(02)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cartier L, Hartley O, Dubois-Dauphin M, Krause KH. Chemokine receptors in the central nervous system in brain inflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:16–42. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2004.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen CH, Chen JH, Chen SY, Liao SL, Raung SL. Upregulation of RANTES gene expression in neuroglia by Japanese encephalitis virus infection. J Virol. 2004;78:12107–19. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12107-12119.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dejda A, Sokolowska P, Nowak JZ. Neuroprotective potential of three neuropeptides PACAP38, VIP and PHI. Pharmacol Rep. 2005;57:307–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diglio CA, Liu W, Grammas P, Giacomelli F, Wiener J. Isolation and characterization of cerebral resistance vessel endothelium in culture. Tissue Cell. 1993;25:833–46. doi: 10.1016/0040-8166(93)90032-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorheim MA, Tracey WR, Pollock JS, Grammas P. Nitric oxide synthase activity is elevated in brain microvessels in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;205:659–65. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eugenin EA, D’Aversa TG, Lopez L, Calderon TM, Berman JW. MCP-1 (CCL2) protects human neurons and astrocytes from NMDA or HIV-tat-induced apoptosis. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1299–311. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eugenin EA, Osiecki K, Lopez L, Goldstein H, Calderon TM, Berman JW. CCL2/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mediates enhanced transmigration of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-infeted leukocytes across the blood-brain barrier: a potential mechanism of HIV-CNS invasion and neuroAIDS. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1098–106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3863-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galimberti D, Schoonenboon N, Scheltens P, Fenoglio C, Bouwman F, Venturelli E, Guidi I, Blankenstein MA, Bresolin N, Scarpini E. Intrathecal chemokine synthesis in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:538–43. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.4.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gangemi S, Basile G, Merendino RA, Epifanio A, Di Pasquale G, Ferlazzo B, Nicita-Mauro V, Morgante L. Effect of levodopa on interleukin-15 and RANTES circulating levels in patients affected by Parkinson’s disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2003;12:251–3. doi: 10.1080/09629350310001599701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grammas P. A damaged microcirculation contributes to neuronal cell death in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:199–205. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(00)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grammas P, Moore P, Weigel PH. Microvessels from Alzheimer’s disease brain kill neurons in vitro. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:337–42. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65280-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grammas P, Ovase R. Inflammatory factors are elevated in brain microvessels in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2001;22:837–42. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(01)00276-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grammas P, Samany PG, Thirumangalakudi L. Thrombin and inflammatory proteins are elevated in Alzheimer’s disease microvessels: implications for disease pathogenesis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:51–8. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grzybicki D, Moore SA, Schelper R, Glabinski AR, Ransohoff RM, Murphy S. Expression of monocyte chemoattractant protein (MCP-1) and nitric oxide synthase-2 following cerebral trauma. Acta Neuropathol (Berl) 1998;95:98–103. doi: 10.1007/s004010050770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamdheydari L, Christov A, Ottman T, Hensley K, Grammas P. Oxidized LDLs affect nitric oxide and radical generation in brain endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;11:486–90. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heneka MT, O’Banion MK. Inflammatory processes in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:69–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ignatov A, Robert J, Gregory-Evans C, Schaller HC. RANTES stimulates Ca2+ mobilization and inositol triphosphate (IP3) formation in cells transfected with G protein-coupled receptor 75. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:490–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Johnstone M, Gearing AJ, Miller KM. A central role for astrocytes in the inflammatory response to beta-amyloid; chemokines, cytokines and reactive oxygen species are produced. J Neuroimmunol. 1999;93:182–93. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(98)00226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerschensteiner M, Stadelmann C, Dechant G, Wekerle H, Hohfeld R. Neurotrophic cross-talk between the nervous and immune systems: implications for neurological diseases. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:292–304. doi: 10.1002/ana.10446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khachaturian ZS. Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1985;42:1097–1105. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1985.04060100083029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lee HP, Jun YC, Choi JK, Kim JI, Carp RI, Kim YS. The expression of RANTES and chemokine receptors in the brains of scrapie-infected mice. J Neuroimmunol. 2005;158:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lin YL, Liu CC, Chuang JI, Lei HY, Yeh TM, Lin YS, Huang YH, Liu HS. Involvement of oxidative stress, NF-IL-6, and RANTES expression in dengue-2-virus-infected human liver cells. Virology. 2000;276:114–26. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGeer PL, Rogers J, McGeer EG. Inflammation, anti-inflammatory agents and Alzheimer disease: the last 12 years. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:271–6. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9s330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neuroinflammation Working Group. Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2000;21:382–421. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orellana DI, Quintanilla RA, Maccioni RB. Neuroprotective effect of TNF alpha against the beta-amyloid neurotoxicity mediated by CDK5 kinase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1773:254–63. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pease JE. Tails of the unexpected – an atypical receptor for the chemokine RANTES/CCL5 expressed in brain. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;149:490–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Re DB, Przedborski S. Fractalkine: moving from chemotaxis to neuroprotection. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:859–61. doi: 10.1038/nn0706-859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reynolds A, Laurie C, Lee Mosley R, Gendelman HE. Oxidative stress and the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disorders. Int Rev Neurobiol. 2007;82:297–325. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(07)82016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rostene W, Buckingham JC. Chemokines as modulators of neuroendocrine functions. J Mol Endocrinol. 2007;38:351–3. doi: 10.1677/JME-07-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarfo BY, Armah HB, Irune I, Adjei AA, Olver CS, Singh S, Lillard JW, Jr, Stiles JK. Plasmodium yoelii 17XL infection up-regulates RANTES, CCR1, CCR3 and CCR5 expression, and induces ultrastructural changes in the cerebellum. Malar J. 2005;16:63. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-4-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sastre M, Klockgether T, Heneka MT. Contribution of inflammatory processes to Alzheimer’s disease: molecular mechanisms. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2006;24:167–76. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2005.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sautter NB, Shick EH, Ransohoff RM, Charo IF, Hirose K. CC chemokine receptor 2 is protective against noise-induced hair cell death: studies in CX3CR1(+/GFP) mice. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2006;7:361–72. doi: 10.1007/s10162-006-0051-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sharma V, Mishra M, Ghosh S, Tewari R, Basu A, Seth P, Sen E. Modulation of interleukin-1beta mediated inflammatory response in human astrocytes by flavonoids: implications in neuroprotection. Brain Res Bull. 2007;73:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shi MM, Godleski JJ, Paulauski JD. Regulation of macrophage inflammatory protein- 1α mRNA by oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:5878–5883. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.10.5878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stoll G, Jander S, Schroeter M. Cytokines in CNS disorders: neurotoxicity versus neuroprotection. J Neural Transm Suppl. 2000;59:81–9. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7091-6781-6_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stoll G, Jander S, Schroeter M. Detrimental and beneficial effects of injury-induced inflammation and cytokine expression in the nervous system. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2002;513:87–113. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-0123-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Szekely CA, Town T, Zandi PP. NSAIDs for the chemoprevention of Alzheimer’s disease. Subcell Biochem. 2007;42:229–48. doi: 10.1007/1-4020-5688-5_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tabakman R, Lecht S, Sephanova S, Arien-Zakay H, Lazarovici P. Interactions between the cells of the immune and nervous system: neurotrophins as neuroprotection mediators in CNS injury. Prog Brain Res. 2004;146:387–401. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(03)46024-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thirumangalakudi L, Samany PG, Owoso A, Wiskar B, Grammas P. Angiogenic proteins are expressed by brain blood vessels in Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;10:111–8. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-10114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thirumangalakudi L, Yin L, Rao HV, Grammas P. IL-8 induces expression of matrix metalloproteinases, cell cycle and pro-apoptotic proteins, and cell death in cultured neurons. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:305–11. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tripathy D, Thirumangalakudi L, Grammas P. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein 1-alpha is elevated in Alzheimer’s vessels and is regulated by oxidative stress. J Alzheimers Dis. 2007;11:447–55. doi: 10.3233/jad-2007-11405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Valerio A, Ferrario M, Martinez FO, Locati M, Ghisi V, Bresciani LG, Mantovani A, Spano P. Gene expression profile activated by the chemokine CCL5/RANTES in human neuronal cells. J Neurosci Res. 2004;78:371–82. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volk T, Hensel M, Schuster H, Kox WJ. Secretion of MCP-1 and IL-6 cytokine stimulated production of reactive oxygen species in endothelial cells. Mol Cell Biochem. 2000;206:105–12. doi: 10.1023/a:1007059616914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xia MQ, Hyman BT. Chemokines/chemokine receptors in the central nervous system and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurovirol. 1999;5:32–41. doi: 10.3109/13550289909029743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]