Abstract

BACKGROUND

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS), a severe consequence of the Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, is associated with craniofacial defects, mental retardation, and stunted growth. Previous studies in C57BL/6J and C57BL/6N mice provide evidence that alcohol-induced pathogenesis follows early changes in gene expression within specific molecular pathways in the embryonic headfold. Whereas the former (B6J) pregnancies carry a high-risk for dysmorphogenesis following maternal exposure to 2.9 g/kg alcohol (two injections spaced 4.0 h apart on gestation day 8), the latter (B6N) pregnancies carry a low-risk for malformations. The present study used this murine model to screen amniotic fluid for biomarkers that could potentially discriminate between FAS-positive and FAS-negative pregnancies.

METHODS

B6J and B6N litters were treated with alcohol (exposed) or saline (control) on day 8 of gestation. Amniotic fluid aspirated on day 17 (n = 6 replicate litters per group) was subjected to trypsin digestion for analysis by matrix-assisted laser desorption–time of flight mass spectrometry with the aid of denoising algorithms, statistical testing, and classification methods.

RESULTS

We identified several peaks in the proteomics screen that were reduced consistently and specifically in exposed B6J litters. Preliminary characterization by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and multidimensional protein identification mapped the reduced peaks to alpha fetoprotein (AFP). The predictive strength of AFP deficiency as a biomarker for FAS-positive litters was confirmed by area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

CONCLUSIONS

These findings in genetically susceptible mice support clinical observations in maternal serum that implicate a decrease in AFP levels following prenatal alcohol damage.

Keywords: alcohol, pregnancy, FAS, FASD, mouse, C57BL/6J, C57BL/6NCrl, amniotic fluid, proteomics, Random Forest, alpha fetoprotein

INTRODUCTION

The Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) comprises a subset of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) and includes a consistent pattern of physical abnormalities in the face and eye, with intrauterine growth retardation and neuro-developmental deficits (Jones et al., 1973). Although the consequences of prenatal alcohol damage have been well-characterized in children, the full range of effects in FAS/FASD remains difficult to diagnose (Bertrand et al., 2004). Developmental stage at the time of prenatal alcohol exposure, and maternal genotype or maternal-fetal interactive effects, coupled with differing patterns and amounts of alcohol consumption by the mother account for some of the known variability and uncertainty in alcohol-induced end points (Streissguth et al., 1996; Viljoen et al., 2001; Sulik, 2005).

Early detection of FAS/FASD is highly desired for the purposes of early intervention, both prenatally in terms of reducing alcohol consumption through the remainder of pregnancy, and postnatally, in terms of initiating measures that may improve the child's performance (Streissguth et al., 1996). As such, research leading to discovery and validation of biomarkers that can better inform healthcare decisions and interventions in alcoholic pregnancies is needed (Bearer et al., 2005; Goodlett et al., 2005). Studies have shown the utility of alcohol-derived fatty acid ethyl esters in the meconium as indicative of maternal alcohol consumption during pregnancy (Bearer et al., 2005). Although this screening may ultimately prove useful to quantify a risky drinking pattern, the extent to which fatty acid ethyl esters address sensitive stages of exposure or the risk for alcohol-related birth defects is not yet clear. Identification of biomarker(s) of effect could strengthen a prenatal alcohol screening program by linking exposure with fetal changes (Goodlett et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2005; Green et al., 2007). The discovery and validation of general and specific biomarkers for FAS/FASD in well-defined animal models can advance this effort.

In the research described here, we tested the hypothesis that protein complexity of the amniotic fluid (AF) can change in association with the risk for alcohol-related birth defects. AF is a colorless composite of water, protein, minerals electrolytes, hormones, environmental pollutants, and exfoliated cells. During the normal course of pregnancy the AF is conditioned by amniocytes that produce cytokines, lipids, prostaglandins, and growth factors in response to local and endocrine signals, and by fetal urination, lung secretion, swallowing, and intestinal absorption (Cheung and Brace, 2005). In amniocentesis some AF is aspirated for diagnostic purposes during the second trimester, usually at 16–18 weeks when the AF peaks in volume. Biochemical analysis of AF can reveal specific developmental disorders; for example, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) is elevated in the AF of fetuses with open NTDs including anencephaly and spina bifida (Jones et al., 2001). In contrast, AFP levels are sometimes abnormally low in AF of fetuses with Down's syndrome (trisomy 21) (Yamamoto et al., 2001). Some fetal testis proteins in the AF were decreased in males born to alcohol users (Westney et al., 1991). Because the human AF proteome database comprises more than 400 different gene products (Tsangaris et al., 2005), a large scale analysis of proteins (proteomics) may reflect multiple changes that can be systematically linked with alcohol-induced birth defects.

Proteomics-based methods have been used to study brains from healthy and chronic alcoholic individuals (Lewohl et al., 2004; Alexander-Kaufman et al., 2006). To our knowledge, no such studies have been performed on AF of alcoholic pregnancies. The present study used a well-defined murine model to screen AF for biomarkers that could potentially discriminate between FAS-positive and FAS-negative pregnancies. This model comprises closely related C57BL/6 mouse strains that respond differently to maternal alcohol exposure on gestation day (GD)8. Whereas C57BL/6J litters (B6J) carry a high-risk for dysmorphogenesis following maternal exposure to two 2.9 g/kg injections of ethanol alcohol spaced 4.0 h apart on GD8, C57BL/6NCrl litters (B6N) carry a low-risk for malformations (Green et al., 2007). AF was harvested on day 17 of gestation to capture the optimal yield of AF (Cheung and Brace, 2005) at a stage in gestation that can identify FAS-positive and FAS-negative litters (Green et al., 2007). We applied statistical methods to proteomics to identify unique signatures in the MALDI-TOF mass spectrum of AF that could be anchored to the risk for FAS and to differentiate between alcohol-exposed litters in the sensitive strain relative to other groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Exposure

C57BL/6J and C57BL/6NCrl mice 18–19 g in weight were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA), respectively. These lines derived from C57BL/6 by strict inbreeding at The Jackson Laboratory (B6J) and the NIH followed by Charles River (B6N) and differ by 1.6% polymorphism in microsatellite markers (Hovland et al., 2000). Mice were housed in static microisolater cages with bedding that was absorbent, non-nutritive, and nontoxic. The colonies cohabited the same animal room and were maintained on a 12 h photoperiod (06.00–18.00 h light). Diet was Purina mouse chow and tap water ad libitum. Mice were acclimated to the room for at least 10 days before breeding. The animal protocol for this study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Louisville. Carbon dioxide asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation was the method of euthanasia.

For timed pregnancies we bred experienced males to nulliparous females (20–22 g body weight on average) for 4–6 h starting at 07.30–8.00 h. Detection of a vaginal plug at 13.30–14.00 h was regarded as evidence of coitus and this day designated GD0. Dams showing 2–3 g weight gain at 09.30 h on GD8 were assumed pregnant (typically four to eight somite pair stage). The experimental design had four treatment groups, with six to seven litters per group as follows: (I) control B6J; (II) alcohol B6J; (III) control B6N; and (IV) alcohol B6N. Treatment used a standard model of i.p. injection of 22% absolute ethanol (v/v) in isotonic saline given on GD8 by two i.p. injections spaced 4 h apart (Webster et al., 1980; Sulik and Johnston, 1983; Sulik et al., 1986; Kotch and Sulik, 1992; Green et al., 2007). Each injection doses the dam with 2.9 g/kg ethanol. Control litters received vehicle (saline) alone in the same manner. All injections were at 0.5 mL per 30 g maternal body weight.

AF Collection

Pregnant dams were euthanized on GD17. After hysterectomy, the uterus was examined for resorptions. Individual intact amniotic sacs containing the fetus were carefully dissected from the myometrium and decidua using fine tweezers and iridectomy scissors. AF was aspirated from each individual AF cavity using a sterile microsyringe and placed in a sterile microcentrifuge tube on wet ice. Fetuses were inspected for evidence of gross malformations, weighed, and fixed (after hypothermia) in neutral-buffered formalin. Phenotype data from this study were combined with similar data from our previous study (Green et al., 2007). Because the “mother” was the unit of exposure in this model, the “litter” comprised the unit of sampling and also was the basis for group comparison. Two-way ANOVA (substrain, treatment, interaction) was fitted to explain the variability in the teratological outcomes using GraphPad Prism version 4.02 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA; www.graphpad.com.) When ANOVA revealed a significant group-wise effect (p ≤ .05), postanalysis was performed using Bonferroni-corrected multiple comparison tests, as indicated.

AF Sample Preparation

The AF was inspected for clarity. Samples that were cloudy or pink were rejected, as were samples from dead fetuses. AF samples were then pooled for fetuses within each litter, except any fetuses with NTDs were processed individually so as not to contaminate the pooled AF with uninformative samples. The AF yield for proteomics analysis was at least 100–150 μL pooled AF for each litter replicate (n = 6 litter replicates). In total we analyzed 24 pooled AF samples from the four groups that met the criteria for analysis, with six samples coming from each group plus a few smaller samples from the grossly abnormal fetuses. AF samples were centrifuged at 800×g for 5 min at 4°C to remove amniocytes. Samples were stored at −20°C until processing. A 50 μL aliquot of AF was placed in a clean microtube with 10 μL 6M urea, vortexed, and left at room temperature for 20 min. The denatured samples were reduced with 10 μL of 20 mM dithiothreitol at 56°C for 45 min and alkylated with 10 μL of 55 mM iodoacetamide at room temperature in the dark. Ultrapure water (10 μL) was added to dilute the urea followed by addition of 10 μL methylated trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI; catalog #V5113, 100 ng/μL) in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate buffer. Samples were incubated overnight at 37°C. Trypsinized digests were desalted via C-18 ZipTip (Millipore, Billerica, MA; catalog #ZTC18SO96) by aspirating three to five times. Digests were washed with 0.1% formic acid and eluted from the ZipTip with 10 μL 60% acetonitrile in 0.1% formic acid.

MALDI-TOF and Tandem MS

Aliquots of AF trypsin hydrolysate were spotted to a MALDI target plate using 10 mg/mL alpha-cyanohydroxyl cinnamic acid solution as the matrix. Tryptic peptide fragments were resolved on a Micromass ToFSpec2E (Micromass/Waters, Milford, MA) mass spectrometer. The instrument was set to reflectron mode using a 337 nm nitrogen laser and the instrument was operated in positive ion mode for the m/z range of 500 to 4,000 Da. Twelve spectra were collected automatically using set locations on each sample well. Each spectrum consisted of 40 laser firings (480 total laser firings) averaged to improve signal-to-noise ratios. Internal tryptic hydrolysis peaks were used to calibrate the instrument to a mass accuracy of 75 ppm or less. Spectral data patterns were compared to a battery of databases that were in-house and on world wide web-based data searching resources for the pattern matching discussed later.

Preprocessing of Mass Spectra

We applied three preprocessing steps: standardization, denoising, and alignment. The first preserved higher molecular mass protein fragments at low abundance by accounting for the nonuniform baseline and variability in maximum intensity across the mass spectra by the method of Satten et al. (2004). In this method, each spectrum was standardized using only information from that spectrum. Let x denote mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) and let y(x) be the corresponding spectral intensity. The spectra are standardized by replacing the intensity y(x) with y*(x) = {y(x) − Q0.5(x)}/{Q0.75(x) − Q0.25(x)}, where Qα(x) is a local estimate of the αth quantile of spectral intensities at m/z ratio x given by

| (1) |

with

| (2) |

where

| (3) |

and, for a set C, I{C} 5 1if C is true and = 0 otherwise. Note that h is a user selectable width defining a neighborhood of x0. In other words, we centered the spectra using a (local) estimate of the median spectral intensity and divided by a local estimate of the interquartile range. We used interquartile range as a measure of scale because it is insensitive to outlier peak intensities. The function Wh(x0, y) is the proportion of weights {1 − (x − x0)2/h2 that correspond to intensities y(x) that are less than or equal to y. This choice for Qα is a variant of that proposed by Ducharme et al. (1995).

The standardized spectra (step 1) were next subjected to a denoising algorithm to separate noise from potential peaks and for additional smoothing and alignment. Although standardized spectra have a common scale and are fairly homoscedastic, they still contain a mixture of noise and signal. Denoising ensures that the features used for classification correspond to real m/z peaks and increases confidence in the scientific validity of the classification procedure (Sorace and Zhan, 2003). Again, we selected a method that uses only the information in a single spectrum. Note that the standardized spectral intensity y*(x) can be negative; in fact the median of the y*(x) values is typically zero. While it may be difficult to separate noise from signal using those standardized intensities that are positive, the negative standardized intensities presumably represent pure noise; therefore, we estimated standard error based on the negative intensities for a spectrum (Satten et al., 2004). We used those m/z's for which the standardized intensities were at least three standard deviations apart from the average standardized intensity.

All spectra following standardization (step 1) and denoising (step 2) were then aligned by a simple binning technique. In step 3 the “features” across spectra were binned into common intervals of bandwidth = 0.1 Da. Maximum intensity within an interval was assigned to the midpoint m/z of the interval. Following alignment the features are hereto forward defined as “peaks” that were subjected to statistical analysis.

Statistical Analysis for Proteomics

A univariate analysis was used to find any peaks that would differentiate between control and exposed samples in the sensitive (B6J) substrain, between control and exposed samples in the insensitive (B6N) substrain, and between control groups in both substrains (B6N, B6J). For each comparison we used ANOVA, taking the mean intensities in the comparison groups and forming t-statistics for each and every peak. Multiple hypothesis correction (Benjamini and Hochberg, 1995) was applied to control the false discovery rate at a 10% level. We also pursued groupwise classification (e.g., FAS-positive vs. FAS-negative) using a Random Forest (RF) method (Breiman, 2001). Considered one of the best off-the-shelf classifiers currently available (Satten et al., 2004), RF returns a list of variables (m/z) that are deemed to be most useful for classifying the group of samples. For each variable (peak) an importance measure is provided that represents the variable's ability to distinguish control versus alcohol-treated samples, and therefore could be a candidate biomarker. Due to the randomness inherent to the algorithm we ran RF multiple times to obtain the best classification rate.

Provisional Peptide Fragment Identification

Uses of MALDI-TOF in proteomics studies prior to trypsin digestion for each protein yields a limited number of peaks spread across a large range of m/z ratios. Provisional identification of some proteins is possible based on searchable properties of the peptides, such as molecular mass. This peptide mass fingerprinting used the Aldente search engine (Tuloup et al., 2002; http://www.expasy.org/tools/aldente/) with the following search parameters: molecular mass range taken to be 0 to 150 kDa; fixed modification of cysteine residues by carboxyamidomethylation; variable oxidation modification of methionine; no restriction placed on isoelectric point; and species selected as Mus musculus and genus Rodentia. Because each peptide may produce a range of fragments after trypsinization the complexity of the mass spectrum increases dramatically, resulting in more peptide fragments that are displayed over a tighter range of m/z ratios (e.g., mostly below 3,000 Da). Thus, peptide mass fingerprinting was coupled with liquid chromatography with tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) or multidimensional protein identification technology (MuDPIT) to derive sequence information on some of the peptides. For LC-MS/MS, AF samples were denatured and digested as above, desalted on a C18 spin column, and fractionated with strong cation exchange resin. Strong cation exchange fractions were concentrated to ~1 μL with a SpeedVac and diluted with 5% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid to ~7.5 μL. Some fractions were subjected to analysis on a Waters CapLC coupled to a Waters Q-TOF APIUS mass spectrometer. The LC eluate was coupled to a nano-LC sprayer and MS/MS spectra were acquired with data-dependent scanning. Only ions with 2+,3+,or 4+ charges were selected for MS/MS analysis. MuDPIT analysis (Washburn et al., 2001; Wolters et al., 2001) included salt pulses given to free peptides from cation-exchange resin, reversed phase resin separation, and MS/MS of eluted peptide fragments. For both LC-MS/MS and MuDPIT the MS/MS spectra were searched against Swiss-Prot database with Protein-Lynx 4.0. The mass error allowed was 25 ppm and a minimum three consecutive residues were required for a positive match.

Following preliminary characterization an in silico trypsin digestion was performed to generate the peptide fragment patterns of candidate proteins. This method used ProteinProspector v4.0.8 (http://prospector.ucsf.edu/), with “trypsin” selected as the enzyme. Other parameters selected included: peptide fragment mass range was 800–4,000 Da, minimum fragment length of five, maximum of two missed cleavages allowed, and cysteine modification using carbamidomethylation.

RESULTS

Fetal Characteristics

Results from teratological evaluation (this study) were combined with similar data from the previous study (Green et al., 2007) to gauge the net response between B6J and B6N pregnancies. Results on GD17 are shown for mean incidence rate of resorptions, mean fetal weight, and mean percentage of viable fetuses with overt malformations (Table 1). Mean resorption rates were 9.2% for the control and exposed B6N litters. Although resorption rates trended higher in exposed B6J litters (29.2% resorptions) versus control B6J litters (13.1% resorptions), due to highly variable litter effects the differences in resorption rates were not statistically significant. Mean fetal weight was reduced in both substrains following alcohol exposure (9–11% reduction vs. controls). Two-way ANOVA (treatment, substrain, interaction) identified significant treatment-related effects. Malformations mostly involved the eye (coloboma, microphthalmia) and were significant for treatment (p < .001) and treatment × substrain interaction (p = .006). Postanalysis localized the significant effects to the exposed B6J group. Malformation rates were 26.0% in exposed B6J pregnancies versus 6.0% in exposed B6N pregnancies. Consistent with the previous study (Green et al., 2007), these findings suggest that we may define sensitivity to prenatal alcohol based on increased risk for malformations (and resorptions), because fetal weight reduction was evident in either substrain under the treatment conditions employed here. B6J pregnancies carry a high-risk for dysmorphogenesis following maternal exposure to 2.9 g/kg alcohol whereas B6N pregnancies carry a low-risk.

Table 1.

Fetal Effects of GD8 Alcohol Exposure in B6J and B6N Pregnancies Evaluated on GD17

| Litters | Resorptions | Fetal weight | Malformations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Substrain | Group | (n) | (% per litter) | (mean g per fetus) | (% per litter) |

| B6J | Control | 22 | 13.1 ± 3.6 | 0.725 ± 0.025 | 0.0 ± 0.0 |

| B6J | Alcohol | 16 | 29.2 ± 6.4 | 0.647 ± 0.022* | 26.0 ± 7.8*** |

| B6N | Control | 20 | 9.2 ± 2.9 | 0.735 ± 0.021 | 1.9 ± 1.4 |

| B6N | Alcohol | 19 | 9.2 ± 5.5 | 0.667 ± 0.027** | 6.0 ± 2.8 |

| Two-way ANOVA (p-value) | Treatment | 0.057 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |

| Substrain | 0.064 | 0.509 | 0.052 | ||

| Interaction | 0.239 | 0.643 | 0.006 | ||

Mean ± standard error, data compiled from previous (Green et al., 2007) and present studies. Bonferroni-corrected t test for control (2 × saline, GD8) versus alcohol (2 × 2.9 g/kg ethanol, GD8) groups within each substrain;

p ≤ .05,

p ≤ .01,

p ≤ .001.

Comparative Analysis of Aligned Mass Spectra

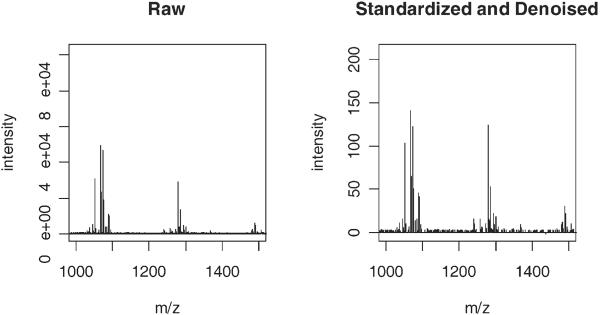

AF was aspirated on GD17 and pooled for proteomics screen. Samples were pooled within a litter avoiding any dead fetuses, bloody or cloudy AF aspirates, or fetuses with open NTDs. AF passing acceptance criteria (n = 6 per group) was trypsinized for direct analysis by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. Typical mass spectrum profiles are shown for control and alcohol-exposed B6J samples for the 500–4,000 m/z region (Fig. 1) and to demonstrate the signal amplification on raw profiles preprocessed through the standardization and denoising algorithms (Fig. 2). Although peak sizes in the MALDI-TOF profiles are not considered to reflect an accurate quantitative measure of peptide fragments, the alignment of six replicated litters per treatment group returned a robust reduction in several peaks across the different biological conditions of the experiment. Three biologically relevant groupwise comparisons were considered: control versus alcohol-exposed samples in B6J (high-risk) pregnancies; control versus alcohol-exposed samples in B6N (low-risk) pregnancies; and control groups in B6J versus B6N pregnancies. The most important classifying m/z peaks are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1.

Sample MALDI-TOF spectrum of murine amniotic fluid samples collected on GD17. Samples from control (A) and alcoholic (B) B6J mouse fetuses: 50 μL aliquots were digested with methylated trypsin and 1 μL aliquots were prepared in an alpha-cyano matrix for linear and reflected MALDI-TOF.

Figure 2.

Preprocessing effects. Example of raw (left panel) and preprocessed (right panel) mass spectra (1,000–1,500 m/z region).

Table 2.

Significantly Altered (Reduced) Mass Spectrum Peaks Identified in the Preliminary Murine Amniotic Fluid Proteomics Screen

| Group comparison (n = 6) | Significantly altered peaks (m/z) | Top-significant classifiers (m/z) |

|---|---|---|

| B6J control vs. exposed | 3,163.5 | 3,163.5 |

| 1,495.8 | 1,495.8 | |

| 1,369.6 | ||

| B6N control vs. exposed | None | None |

| B6J control vs. B6N control | 3,163.5 | 3,163.5 |

| 2,802.3 | ||

| 2,228.2 |

Spectra of mass/charge (m/z) ratios from trypsinized samples by MALDI-TOF in reflectron mode were preprocessed by the three-step schema (standardized, denoised, aligned) and subjected to statistical analysis (n = 6 independent litters per analysis).

Analysis of the control versus alcohol-exposed B6J samples returned three affected m/z peaks with intensities that were reduced in a highly-significant manner, with p values well below 0.00001: m/z = 3,163.5, 1,495.8, and 1,369.6 (Table 2). These changes were evident irrespective of the number of malformed fetuses per litter in the overall AF sample prior to, or after, exclusions of NTDs or bloody/cloudy samples. As such, there was no bias in those AF samples that met criteria in terms of the number of malformed fetuses in the sample by group, relative to the number of malformed fetuses per group in the overall sample prior to exclusions. In contrast, a comparison of B6N samples revealed no peaks that were differentially affected by alcohol in comparison to the controls. Thus, preliminary screening of AF peptides revealed a consistent display of peptide fragments across samples and a significant differential display of several peaks in the high-risk (B6J) pregnancies, but not in the low-risk (B6N) pregnancies. One of these peaks (3163.5) was significantly different in comparing control pregnancies between the two substrains.

We next analyzed the AF peptide fragment profiles to determine which specific peaks would discriminate the FAS-positive group. Two of the top three altered peaks in alcohol-exposed B6J pregnancies, namely m/z values 3,163.5 and 1,495.8, were also amongst the most important variables to classify the samples (Table 2). Repeated use of the RF algorithm yielded classification accuracy as high as 75 versus 75% predicted for a random classifier that ignores the data. Therefore, in a limited sample size of n = 6 we achieved reasonable success in distinguishing the FAS-positive group using straight MALDI-TOF analysis of the trypsinized AF sample. Peak 1,495.8, which was the second most significant peak in terms of the univariate t test, emerged as a strong diagnostic biomarker based on importance measures for classifying the alcohol-exposed B6J proteomic profiles across multiple RF runs (Table 2). In contrast, repeated use of the RF algorithm failed to classify alcohol-exposed and control B6N proteomic profiles. This method yielded 21–28% classification accuracy, which is even worse than purely random assignment (50%) and well-below the 75% accuracy with the B6J comparison. Again, this is consistent with the FAS phenotype anchor.

Running the RF procedure to compare B6J and B6N control groups yielded classification accuracies up to 65%, with three peaks of m/z = 3,163.5, 2,802.3, and 2,228.2 emerging as the top-significant classifiers (Table 2). Although marginal in accuracy by recursive RF, one of these peaks (3,163.5) was significantly different at a p-value well-below .00001. Another peak (2,228.2) trended toward the effect but was not statistically significant, perhaps as a limitation of the small sample size (n = 6).

Specificity-Sensitivity Analysis

Area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUROC) was computed to determine the predictive classification power (sensitivity/specificity) of diagnostic peaks identified in the MALDI-TOF screen. To this end, we selected the top five peaks (peaks 1–5) with the largest absolute t statistic with regards to the capacity to differentiate AF proteomic profiles between control and alcohol-exposed B6J pregnancies. The first three of these (peaks 1–3) were statistically significant after multiple hypotheses correction using Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate control at 10%. Due to the limitation in sample sizes (n = 6), we generated 50 bootstrap samples from the original samples to perform a cross-validatory calculation (Efron and Tibshirani, 1993) and determine ROC of a linear discriminant classifier using these peaks (Datta and de Padilla, 2006). Bootstrapped samples were randomly divided into training set (35 samples) and test set (15 samples) from each group for linear discriminant analysis (Fisher, 1936) with varying classification cut-offs. Based on results for the test samples, we plotted 1-specificity values against the sensitivity values in order to construct the ROC curves (Fig. 3). The maximum AUROC (1.0) was achieved using intensity values of peaks 1–3 or peaks 1–4, indicating ideal classification performance. We also obtained unity AUROCs constructed with any of the top three peaks together with peaks 4–5; however, AUROC dropped slightly (0.92) when the ROC curve was drawn using only two channels (peaks 4 and 5).

Figure 3.

Specificity-sensitivity analysis of the five top significant classifier peaks in the FAS-positive diagnostic profile. ROC curves were drawn for ROC characteristics of the top five peaks from MALDI-TOF based on linear discriminant classifier of alcohol-exposed and control B6J samples (named peaks 1–5, based on p values). Bootstrapped samples were randomly divided into training and test sets for linear discriminant analysis with varying classification cut-offs. ROC curves plotted 1-specificity versus sensitivity for peaks 1–4 (left panel) and peaks 4–5 (right panel). Maximum area under the ROC curve (1.0) was achieved using peaks 1–4, and near-unity (0.92) with peaks 4–5.

Provisional Peptide Identification

Several more formal approaches were used for further characterization of discriminating peaks in the MADLI-TOF screen. First, peptide mass fingerprinting was applied to the MALDI-TOF mass spectra. Because we were dealing with clean AF samples we assumed the complexity of proteins was low enough for at least some useful information to be drawn regarding the most abundant peptide species present. Among the top-scoring candidates the most frequent occurrences were: mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor (P02772), mouse serum albumin precursor (P07724), and myosin regulatory light chain 2 skeletal muscle isoform (P97457). These peptides were detected in essentially all B6J and B6N control samples. Many peptides showed weaker redundancy across samples; a typical example is shown for control and alcohol-exposed B6J and B6N samples with regards to the five top-scoring candidate peptides (Table 3). In all four cases the top two scoring candidates were, respectively, alpha-fetoprotein and serum albumin. Whereas both proteins belong to the albuminoid gene family the current AF screen did not indicate differences in the MALDI-TOF peptides derived from serum albumin.

Table 3.

Top Five Scoring Proteins (in Terms of Lowest pValue from MALDI-TOF Comparison) Shown for Representative Control and Alcohol-Exposed AF Samples in B6J and B6N Pregnancies

| Name of candidate protein (UniProt) | Primary accession number | Amino acids | Coverage |

|---|---|---|---|

| B6J (saline) | |||

| Mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor | P02772 | 605 | 43% |

| Mouse serum albumin precursor | P07724 | 608 | 18% |

| N-terminal acetyltransferase complex ARD1 subunit homolog A | Q9QY36 | 235 | 44% |

| Short/branched chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase, mitochondrial precursor | Q9DBL1 | 432 | 30% |

| Myosin regulatory light chain 2, skeletal muscle isoform | P97457 | 169 | 38% |

| B6J (ethanol) | |||

| Mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor | P02772 | 605 | 30% |

| Mouse serum albumin precursor | P07724 | 608 | 23% |

| Phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase, mitochondrial precursor | O70325 | 197 | 42% |

| Serine/threonine-protein kinase TBK1 | Q9WUN2 | 729 | 22% |

| Potassium channel tetrameriesation | Q9D7X1 | 259 | 35% |

| B6N (saline) | |||

| Mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor | P02772 | 605 | 45% |

| Mouse serum albumin precursor | P07724 | 608 | 34% |

| Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 2 | P58801 | 539 | 34% |

| Vinculin | Q64727 | 1,066 | 19% |

| Caspase-4 subunit p10 | P70343 | 373 | 58% |

| B6N (ethanol) | |||

| Mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor | P02772 | 605 | 36% |

| Mouse serum albumin precursor | P07724 | 608 | 21% |

| Putative Sp100-related protein | Q99388 | 208 | 49% |

| Spermatid-specific linker histone H1-like protein | Q9QYL0 | 170 | 51% |

| Succinyl-CoA ligase | Q9Z218 | 433 | 33% |

Based on the Aldante search engine (http://www.expasy.org/tools/aldente/).

An effort was made using in silico trypsin digestion to map the top peaks identified by statistical analysis (Table 2) onto the most abundant proteins identified by peptide mass fingerprinting. Although we could not identify the most significantly reduced peak in the alcohol-exposed B6J pregnancies (m/z = 3,163.5), the second-most significantly reduced peak, which was also the second-most important classifying peak (m/z = 1,495.8), was successfully mapped to mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor. The third-most significantly reduced peak (m/z = 1,369.6) was also identified as a potential peptide of mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor, assuming one missed in silico cleavage. Analysis of some B6J samples by LC-MS/MS and MuDPIT further implicated both peaks 1,495.8 and 1,369.6 (assuming one missed cleavage) as trypsin-induced peptide fragments cleaved from mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor protein. The related amino acid sequences corresponded to residues 514–526 (DETYAPPPFSEDK) and 191–201 (ADNKEECFQTK), respectively, of this 605 amino acid protein. Furthermore, among the top 20-altered peaks observed in alcohol-exposed B6J samples in terms of absolute t statistic, nine of them (m/z = 1,495.8, 1,369.6, 1,774.9, 1,556.8, 1,638.8, 1,337.7, 1,685.9, 897.5, 897.6) were predicted from an in silico trypsin cleavage of mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor protein. These matches cover different regions of the protein and include bins of 100, 200, 300, and 500 amino acid residues. Therefore, we conclude from these findings that reduced detection of mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor protein accounted for two of three major classifier peaks that can distinguish the alcohol-exposed B6J litters. The third classifier (peak 3,163.5) differentiated between the sensitive strain and the insensitive strain in the unexposed, but also significantly differentiated between the exposed and unexposed in the sensitive strain; however, the identity of this peptide was not determined in the present study. By these criteria mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor protein levels were not altered in the alcohol-exposed B6N pregnancies. A few B6J fetuses were excluded from AF pooling that may have been dead or severely malformed for days prior to AF procurement. Although it is feasible to assay AF from individual gravida, such abnormal fetuses must ultimately be procured at a much earlier gestational stage to be useful. In fact, the individual AF from a few severely malformed fetuses from the exposed B6J group that we did examine by MALDI-TOF profiles were not informative because there were no abnormal fetuses to compare from the control B6J or exposed B6N groups (not shown).

DISCUSSION

The optic primordium is a critical target of alcohol in experimental teratogenesis and in FASD (Green et al., 2007; Higashiyama et al., 2007). Early gestational exposure to alcohol reprograms genetic networks during initiation of the FAS in mice (Green et al., 2007). That effect was demonstrated in the GD8 mouse embryonic headfold at 3 h following a single maternal injection of ethanol (2.9 g/kg). In the aftermath of global genetic responses that clearly differentiated high-risk (B6J) from low-risk (B6N) inbred lines of C57BL/6 mice (Green et al., 2007), results from the present study show that dysmorphogenesis was associated with eventual changes in the AF-compartment of the fetus that could be detected by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry and specialized data analysis methods. Because the current FAS animal model is not highly penetrant the pooled AF samples would have included grossly unaffected as well as malformed fetuses. Both pedigrees (B6J, B6N) were exposed to alcohol and for both test substrains we measured an effect of the alcohol exposure in terms of fetal weight reduction, but only one substrain showed a response in terms of increased malformation rates. In contrast to malformations, the fetal weight reduction was more evenly distributed across a litter. Thus, the general and specific biomarkers for FAS/FASD that might emerge from such an AF analysis on GD17 following acute maternal alcohol intoxication on GD8 can only be anchored to the increased risk for malformations on a litter basis. These changes may be summarized as follows: (a) the AF proteome in alcohol-exposed B6J pregnancies showed a highly significant drop in the abundance of three peaks (m/z = 3,163.5, 1,495.8, 1,369.6); (b) ROC analysis found these peaks to be highly sensitive and specific for classifying the susceptible group by exposure; (c) two of these peaks (1,495.8, 1,369.6) mapped to mouse alpha-fetoprotein precursor protein, as did 9 of the 20 most altered peaks based on in silico digestion; and (d) none of these peaks were found to be altered by alcohol in the B6N substrain. Taken together, these findings suggest that discrete changes to the AF proteome can be anchored to the observed risk for alcohol-related birth defects in a mouse model for FAS. We interpret these changes to represent an ability to better identify fetuses more likely to be affected with FAS dysmorphology in association with the incidence rate of detectable malformations.

Recently, alpha-fetoprotein has been considered as a biomarker for perinatal distress (Mizejewski, 2007). Discordant levels of AFP in AF have been indicative of structural defects in the brain and spinal cord (elevated) or low birth weight-fetal growth restriction (reduced). In general, developmental regulation of AFP may be connected with growth and differentiation or perinatal stressors as reflected in the functional role attributed to AFP in small molecule binding and transport (e.g., fatty acids, retinoids, hormones, heavy metals, drugs, and toxicants). Although interesting for the pathogenesis of developmental defects, this is dispensable for major organogenesis as shown by the lack of malformations in AFP knockout mice (Gabant et al., 2002).

Realization of alpha-fetoprotein as a general biomarker for FAS has practical implications for understanding alcohol's mode of action on the fetus as well as potential translation to clinical diagnostics. On one hand, alpha-fetoprotein is released from various cell types and gains access to the extracellular fluids such as the AF compartment (AF-AFP) and maternal serum (MS-AFP). Therefore, lower amounts of AF-AFP may secondarily yield lower MS-AFP levels that could, ultimately, reflect an increased risk of alcohol-related malformations in babies whose mothers drink heavily during pregnancy. In fact, low MS-AFP was found to predict FAS correctly in 59% of alcoholic pregnancies (Halmesmaki et al., 1987). That study followed several standard diagnostic proteins (human placental lactogen, pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein, and alpha-fetoprotein) in 35 pregnant problem drinkers and 14 abstinent control women, and concluded that low alpha-fetoprotein and pregnancy specific beta-1-glycoprotein in maternal serum were useful indicators in predicting FAS. We arrived at the same link between alpha-fetoprotein and FAS through a completely independent, non a priori discovery-based screen of the AF proteome and support the scientific justification for monitoring MS-AFP as part of prenatal care of drinking women and early screening for alcohol-damaged fetuses.

On the other hand, the reduction in AF-AFP raises questions regarding alcohol's mode of action on the AF proteome. The presence of alpha-fetoprotein has been detected almost universally in postimplantation embryos, yolk sac, amnion, embryonic disc, and early primitive streak stages for all mammalian species studied so far (Mizejewski, 2004). Apart from the long-running debate on alpha-fetoprotein's role in brain development, elevated MS-AFP is a clinical biomarker for NTDs such as spina bifida or anencephaly (Brock and Sutcliffe, 1972). The failure of neural tube closure results in leakage of this serum protein into the AF and MS at higher levels than normal. In contrast, MS-AFP is abnormally low in some pregnancies that carry trisomy 21 (Davis et al., 1985). The clinical “triple test” performed at 14–22 weeks of pregnancy is used to screen fetal and placental products in serum samples of expectant mothers >35 years in age to detect trisomy 21 (Spencer et al., 1997; Caserta et al., 1998; Wald et al., 2006a,b; Mizejewski, 2007). This test measures alpha-fetoprotein levels along with unconjugated estradiol and human chorionic gonadotropin that are reduced in trisomy 21 pregnancies.

The alpha-fetoprotein precursor is synthesized at high levels by fetal liver cells and visceral yolk sac endodermal cells. Thus, acute gestational exposure to alcohol likely alters the AF proteome as a secondary consequence of fetal development. Because fetal growth retardation was observed in both strains (B6J, B6N) but reduced AFP was detected only in one strain (B6J), the data do not suggest that growth retardation may have affected the AFP level produced in the fetal liver. Furthermore, we are not aware of studies that implicate liver dysfunction in FAS children; however, the drop in AF-AFP could reflect the aftermath of acute gestational alcohol exposure on liver and/or yolk sac development. This might have implications on multiple tissues because alpha-fetoprotein functions as a binding protein for small molecules such as vitamin D, estrogens, fatty acids, and metals (Mizejewski, 2004; Gitlin and Boesman, 1966; Attardi and Ruoslahti, 1976). In addition to its role as a molecular troubleshooter alpha-fetoprotein contains sequence motifs that render it a druggable target in diagnostics or therapeutics (Mizejewski, 2004; Uriel, 1989). Perhaps the motif sequence DETYAPPPFSEDK (m/z = 1,495.8) could provide a molecular target for early FAS diagnosis or therapeutic intervention, through an understanding of the small molecules that might bind to this peptide domain. Additional studies will be needed to establish the link between dysregulation of the embryonic transcriptome (Green et al., 2007) and disruption of alpha-fetoprotein in the AF proteome (current study) following gestational alcohol exposure.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Kenneth Lyons Jones, M.D. of the University of California San Diego for thoughtful input.

Grant sponsor: NIH P20-RR/DE17702 (S. D.).

Grant sponsor: NIH/NIEHS P30ES014443-01A1 (S. D.)

Grant sponsor: NIH RO1-AA13205 (T. B. K.).

Grant sponsor: Biomolecular Mass Spectrometry Laboratory; Grant number: S10-RR11368.

Grant sponsor: State of Kentucky Physical Facilities Trust Fund (W. M. P.).

Grant sponsor: University of Louisville School of Medicine (W. M. P.).

Grant sponsor: University of Louisville Research Foundation (W. M. P.).

Grant sponsor: Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada (L. B. R.).

Footnotes

The authors declare they have no competing financial interests. Although Dr. Knudsen's current address is the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency this work was conducted and analyzed while he was on the faculty at University of Louisville. The content does not reflect the views of the Agency, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendations for use.

REFERENCES

- Alexander-Kaufman K, James G, Sheedy D, et al. Differential protein expression in the prefrontal white matter of human alcoholics: a proteomics study. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:56–65. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attardi B, Ruoslahti E. Foetoneonatal oestradiol-binding protein in mouse brain cytosol is alpha-fetoprotein. Nature. 1976;263:685–687. doi: 10.1038/263685a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bearer CF, Stoler JM, Cook JD, et al. Biomarkers of Alcohol Use in Pregnancy. Alcohol Research and Health, NIAAA publications. 2005;28:38–43. (pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh28-1/38-43.pdf) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J Royal Statist Soc Series B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand J, Floyd RL, Weber MK, et al. Fetal alcohol syndrome: guidelines for referral and diagnosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2004. National Task Force on FAS/FAE. ( http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/fas/documents/FAS_guidelines_accessible.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- Breiman L. Random Forests. Machine Learning. 2001;45:5–32. [Google Scholar]

- Brock DJH, Sutcliffe RG. Alpha-fetoprotein in the antenatal diagnosis of anencephaly and spina bifida. Lancet. 1972;2:197–199. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)91634-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caserta D, Baldi M, Carta G, et al. Tri-test: clinical considerations on 1784 cases. Minerva Ginecol. 1998;50:73–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen SY, Charness ME, Wilkemeyer MF, et al. Peptide-mediated protection from ethanol-induced neural tube defects. Dev Neurosci. 2005;27:13–19. doi: 10.1159/000084528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung CY, Brace RA. Amniotic fluid volume and composition in mouse pregnancy. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:558–562. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S, de Padilla LM. Feature selection and machine learning with mass spectrometry data for distinguishing cancer and non-cancer samples. Statistical Methodology: Special Issue on Bioinformatics. 2006;3:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- Davis RO, Casper P, Huddleston JF, et al. Decreased levels of amniotic fluid AFP associated with Down syndrome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:541–544. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90469-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducharme GR, Gannoun A, Guertin M-C, et al. Reference values obtained by kernel-based estimation of quantile regressions. Biometrics. 1995;51:1105–1116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efron B, Tibshirani RJ. An Introduction to the Bootstrap. Chapman & Hall; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RA. The Use of Multiple Measurements in Taxonomic Problems. Ann Eugenics. 1936;7:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Gabant P, Forrester L, Nichols J, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein, the major fetal serum protein, is not essential for embryonic development but is required for female fertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:12865–12870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202215399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin D, Boesman M. Serum AFP, albumin, and -G-globulin in the human conceptus. J Clin Invest. 1966;45:1826–1830. doi: 10.1172/JCI105486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett CR, Horn KH, Zhou FC. Alcohol teratogenesis: mechanisms of damage and strategies for intervention. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:394–406. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green ML, Singh AV, Zhang Y, et al. Reprogramming of genetic networks during initiation of fetal alcohol syndrome. Dev Dynam. 2007;236:613–631. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halmesmaki E, Autti I, Granstrom ML, et al. Prediction of fetal alcohol syndrome by maternal alpha fetoprotein, human placental lactogen and pregnancy specific beta 1-glycoprotein. Alcohol Suppl. 1987;1:473–476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higashiyama D, Saitsu H, Komada M, et al. Sequential developmental changes in holoprosencephalic mouse embryos exposed to ethanol during the gastrulation period. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol. 2007;79:513–523. doi: 10.1002/bdra.20367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovland DN, Jr, Cantor RM, Lee GS, et al. Identification of a murine locus conveying susceptibility to cadmium-induced forelimb malformations. Genomics. 2000;63:193–201. doi: 10.1006/geno.1999.6069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones EA, Clement-Jones M, James OFW, et al. Differences between human and mouse alpha-fetoprotein expression during early development. Ann Hum Genet. 2001;198:555–559. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2001.19850555.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Smith DW, Ulleland CH, et al. Pattern of malformation in offspring of chronic alcoholic mothers. Lancet. 1973;1:1267–1271. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)91291-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotch LE, Sulik KK. Experimental fetal alcohol syndrome: proposed pathogenic basis for a variety of associated facial and brain anomalies. Am J Med Genet. 1992;44:168–176. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320440210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewohl JM, Van Dyk DD, Craft GE, et al. The application of proteomics to the human alcoholic brain. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2004;1025:14–26. doi: 10.1196/annals.1316.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizejewski GJ. Biological roles of alpha-fetoprotein during pregnancy and perinatal development. Exp Biol Med. 2004;229:439–463. doi: 10.1177/153537020422900602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizejewski GJ. Physiology of alpha-fetoprotein as a biomarker for perinatal distress: relevance to adverse pregnancy outcome. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2007;232:993–1004. doi: 10.3181/0612-MR-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satten GA, Datta S, Moura H, et al. Standardization and denoising algorithms for mass spectra to classify whole-organism bacterial specimens. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3128–3136. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorace JM, Zhan M. A data review and re-assessment of ovarian cancer serum proteomic profiling. BMC Bioinformatics. 2003;4:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-4-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer K, Muller F, Aitken DA. Biochemical markers of trisomy 21 in amniotic fluid. Prenat Diagn. 1997;17:31–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Barr HM, Kogan J, et al. Final Report to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), August, 1996. University of Washington, Fetal Alcohol & Drug Unit; Seattle: 1996. Understanding the occurrence of secondary disabilities in clients with fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) and fetal alcohol effects (FAE): Final report to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Tech. Rep. No: 96–06. [Google Scholar]

- Sulik KK. Genesis of alcohol-induced craniofacial dysmorphism. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:366–375. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulik KK, Johnston MC. Sequence of developmental alterations following acute ethanol exposure in mice: craniofacial features of the fetal alcohol syndrome. Am J Anat. 1983;166:257–269. doi: 10.1002/aja.1001660303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulik KK, Johnston MC, Daft PA, et al. Fetal alcohol syndrome and DiGeorge anomaly: critical ethanol exposure periods for craniofacial malformations as illustrated in an animal model. Am J Med Genet (suppl) 1986;2:97–112. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320250614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsangaris G, Weitzdörfer R, Pollak D, et al. The amniotic proteome. Electrophoresis. 2005;26:1168–1173. doi: 10.1002/elps.200406183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuloup M, Hoogland C, Binz PA, et al. A new Peptide Mass Fingerprinting tool on ExPASy: ALDentE.Swiss Proteomics Society 2002 congress. Applied Proteomics. Lausanne (CH) 2002 Dec;:3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Uriel J. The physiological role of alpha-fetoprotein in cell growth and differentiation. J Nucl Med Allied Sci. 1989;33:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljoen DL, Carr LG, Foroud TM, et al. Alcohol dehydrogenase-2*2 allele is associated with decreased prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome in the mixed-ancestry population of the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1719–1722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald NJ, Barnes IM, Birger R, et al. Effect on Down syndrome screening performance of adjusting for marker levels in a previous pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. 2006a;26:539–544. doi: 10.1002/pd.1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wald NJ, Morris JK, Ibison J, et al. Screening in early pregnancy for pre-eclampsia using Down syndrome quadruple test markers. Prenat Diagn. 2006b;26:559–564. doi: 10.1002/pd.1459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washburn MP, Wolters D, Yates JR. Large-scale analysis of the yeast proteome by multidimensional protein identification technology. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:242–247. doi: 10.1038/85686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster WS, Walsh DA, Lipson AH, McEwen SE. Teratogenesis after acute alcohol exposure in inbred and outred mice. Neurobehav Toxicol. 1980;2:227–234. [Google Scholar]

- Westney L, Bruney R, Ross B, et al. Evidence that gonadal hormone levels in amniotic fluid are decreased in males born to alcohol users in humans. Alcohol Alcoholism. 1991;26:403–407. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.alcalc.a045131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolters DA, Washburn MP, Yates JR. An automated multidimensional protein identification technology for shotgun proteomics. Anal Chem. 2001;73:5683–5690. doi: 10.1021/ac010617e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto R, Azuma M, Wakui Y, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein microheterogeneity: a potential biochemical marker for Down's syndrome. Clin Chim Acta. 2001;304:137–141. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(00)00381-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]