Abstract

The purpose of this study was to prospectively compare participant experience and preference of limited preparation computed tomography colonography (CTC) with full-preparation colonoscopy in a consecutive series of patients at increased risk of colorectal cancer. CTC preparation comprised 180 ml diatrizoate meglumine, 80 ml barium and 30 mg bisacodyl. For the colonoscopy preparation 4 l of polyethylene glycol solution was used. Participants’ experience and preference were compared using the Wilcoxon signed rank test and the chi-squared test, respectively. Associations between preference and experience parameters for the 173 participants were determined by logistic regression. Diarrhoea occurred in 94% of participants during CTC preparation. This side effect was perceived as severely or extremely burdensome by 29%. Nonetheless, the total burden was significantly lower for the CTC preparation than for colonoscopy (9% rated the CTC preparation as severely or extremely burdensome compared with 59% for colonoscopy; p < 0.001). Participants experienced significantly more pain, discomfort and total burden with the colonoscopy procedure than with CTC (p < 0.001). After 5 weeks, 69% preferred CTC, 8% were indifferent and 23% preferred colonoscopy (p < 0.001). A burdensome colonoscopy preparation and pain at colonoscopy were associated with CTC preference (p < 0.04). In conclusion, participants’ experience and preference were rated in favour of CTC with limited bowel preparation compared with full-preparation colonoscopy.

Keywords: CT colonography, Gastrointestinal, Colon, Bowel preparation, Patient acceptance, Side effects, Contrast, Faecal tagging

Introduction

Computed tomography (CT) colonography is an established and widely used imaging technique in patients with symptoms of colorectal cancer. In addition, it has been identified as an effective instrument for screening average-risk individuals [1–4]. However, CT colonography requires a cathartic bowel preparation that is burdensome and often considered the most unpleasant part of the examination [5–7].

Several studies have reported promising results for CT colonography with regard to image quality and accuracy after a less extensive bowel preparation [8–12]. Data on acceptance of these limited bowel preparation schemes are however sparse. To our knowledge, three feasibility studies and one accuracy study have investigated patient acceptance of a limited preparation with favourable results [13–16]. To date, no comprehensive data on patient acceptance and preference in a larger cohort have been published.

Therefore, the purpose of our study was to assess intraindividual experience and preference for CT colonography with a limited preparation in comparison to optical colonoscopy with a cathartic preparation in a population at increased risk of colorectal cancer.

Materials and methods

Study population

Patients with a personal or family history of colorectal polyps or cancer were invited to participate in our study [17]. All patients were scheduled for a routine optical colonoscopy at the endoscopy departments of the Academic Medical Center (AMC) or the Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis (OLVG). Exclusion criteria were: age under 18 years, previous reaction to iodine-containing contrast agent, inflammatory bowel disease, familial adenomatous polyposis or previous participation in a research project that involved ionising radiation within 12 months preceding the CT colonography examination. The institutional review board of both hospitals approved the study. All patients gave written informed consent.

Questionnaires

Participants filled out six questionnaires at different time points with regard to (Appendix, Table 4):

Pretest appraisal and post-test experience with the preparation for CT colonography and the preparation for optical colonoscopy.

Pretest appraisal and post-test experience with the CT colonography and optical colonoscopy procedures.

Preference for their future examinations.

Table 4.

Content of questionnaires and number of responses per question

| Parameter | Questionnaire 1 | Questionnaire 2 | Questionnaire 3 | Questionnaire 4 | Questionnaire 5 | Questionnaire 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Where and when completed? | By mail 2 weeks before CTC | In waiting room before CTC | In waiting room after CTC | In waiting room before OC | In recovery room after OC | At home by mail 5 weeks after OC |

| Number of returned questionnaires | 173/173 (100) | 173/173 (100) | 173/173 (100) | 169/173 (98) | 167/173 (97) | 166/173 (96) |

| Baseline characteristics (±) | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Most reluctant factor of the examination | 173/173 (100) | − | − | − | − | 161/173 (93) |

| How burdensome was low-fibre diet? | − | 173/173 (100) | − | − | − | − |

| How burdensome was bisacodyl? | − | 169/173 (98) | − | − | − | − |

| How burdensome were contrast agents | − | 173/173 (100) | − | − | − | − |

| Side effects of the CTC bowel preparation | − | 168/173 (97) | − | − | − | − |

| Total burden of entire bowel preparation | − | 171/173 (99) | − | 165/171 (95) | − | − |

| How painful was procedure? | − | − | 171/173 (99) | − | 167/173 (97) | − |

| How embarrassing was procedure? | − | − | 172/173 (99) | − | 166/173 (96) | − |

| How uncomfortable was procedure? | − | − | 173/173 (100) | − | 164/173 (95) | − |

| Total burden of entire procedure | − | − | 173/173 (100) | − | 167/173 (97) | − |

| Most burdensome aspect of procedure | − | − | 159/173 (92) | − | 162/173 (94) | − |

| Most burdensome preparation; CTC or OC | 162/173 (94)a | − | − | − | 160/173 (92) | 165/173 (95) |

| Most burdensome procedure; CTC or OC | 159/173 (92)a | − | − | − | 159/173 (92) | 164/173 (95) |

| Preference for examination; CTC or OC | − | − | − | − | 164/173 (95) | 166/173 (96) |

Burdensome refers to the extent of burden (e.g. the degree of unpleasantness) that was associated with a particular aspect and rated on a five-point scale: 1, not burdensome; 2, mildly burdensome; 3, moderately burdensome; 4, severely burdensome; 5, extremely burdensome

aParticipants were asked to rate both the individual aspects of the preparation and procedure as well as the entire preparation and procedure as a whole (i.e.=total burden)

Participants’ pretest appraisal was based on previous knowledge of the examinations and on information provided by us (in writing and by phone) and was filled out 2 weeks before CT colonography.

Participants’ experience with the preparation and the procedure was rated using a five-point scale (none, mild, moderate, severe, extreme) and filled out on the day of the examination. Furthermore, after completing both tests participants indicated which event was most burdensome to undergo (CT colonography preparation, the CT colonography procedure, optical colonoscopy preparation, or the optical colonoscopy procedure).

Participants’ preference for CT colonography or optical colonoscopy was rated using a seven-point scale (definitely, probably, possibly CT colonography; indifferent; possibly, probably, definitely optical colonoscopy) and based on the presumption that in 20% of CT colonography examinations a significant lesion would be found that would result in optical colonoscopy referral for polyp removal. Because adverse reactions to tests tend to temper in time and the attitude at that later time point will better reflect the attitude towards future screening, the preference was again assessed 5 weeks later at home. The questionnaires were designed by the Department of Social Medicine [6, 18]

Limited bowel preparation for CT colonography

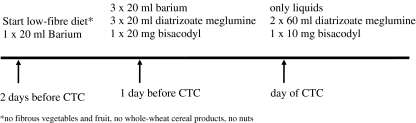

Participants were prepared with a low-fibre diet 2 days before CT colonography. A combination of 80 ml barium sulphate suspension (Tagitol V, E-Z-EM Inc., Westbury, USA) and 180 ml diatrizoate meglumine (200 mg/ml, hospital pharmacy) was prescribed for faecal tagging. Bisacodyl (hospital pharmacy) was given the day before and on the day of the examination to reduce the amount of faeces in the colon (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Limited bowel preparation for CT colonography

CT colonography procedure

CT colonography was performed 1–4 weeks (mean 25 days) before optical colonoscopy. Participants were imaged in the AMC by a dedicated CT colonography technician or research fellow [S.J.]. Through a thin flexible rectal tube the colon was distended automatically with CO2 (ProtocO2l, E-Z-EM, Westbury, NY, USA). Butylscopolamine bromide (20 mg, Buscopan; Boehringer Ingelheim, Ingelheim, Germany) or, if contraindicated, glucagon hydrochloride (1 mg, Glucagon; Novo Nordisk A/S, Bagsvaerd, Denmark) was given intravenously immediately before the imaging. Examinations were performed within a 22-s breath hold on a Philips Mx8000 CT system in the supine and prone positions. The time that patients spent in the CT room and the amount of insufflated CO2 were recorded [A.H.].

Cathartic bowel preparation for optical colonoscopy

Bowel preparation for optical colonoscopy consisted of 4 l of polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution (Klean Prep, Helsinn Birex Pharmaceuticals, Dublin, Ireland). After starting the catharsis participants were not allowed to eat.

Optical colonoscopy procedure

An experienced staff member (gastroenterologist or a gastrointestinal surgeon with average experience of 11 years, range 1–26 years) or a gastroenterology fellow under direct supervision performed the optical colonoscopy in the AMC or the OLVG. Participants received sedatives (5 mg midazolam; Dormicum, Roche, Basel, Switzerland), or analgesics (0.05 mg fentanyl, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Beerse, Belgium or 0.5 mg Rapifen; hospital pharmacy) on request. The endoscopist increased the dose until sedation or pain control was sufficient. Butylscopolamine bromide was administered intravenously. After the examination participants were admitted to the recovery ward for 2 h.

Statistical analysis

Data from participants who completed both examinations were included for analysis.

Pretest appraisal differences between CT colonography and optical colonoscopy and post-test experience differences between the two examinations were tested for statistical significance using the Wilcoxon signed rank test. Differences in preference were tested for significance using the chi-squared test after dichotomisation (preference for CT colonography versus preference for optical colonoscopy); participants who were indifferent were not included. The chi-squared test was also used to analyse differences in preference between the first and the second measurement (immediately post-test versus 5-weeks post-test); p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Univariate logistic regression analysis was used to investigate associations between participants’ preferences for CT colonography or optical colonoscopy (first and second measurement) and patient-related factors: age ≥ 65 years, sex, completion of academic or higher vocational education, income with respect to 27,000 euros (the mean net Dutch annual income per household) or greater, recent symptoms of colorectal cancer, indication for surveillance (personal or familial history of colorectal carcinoma or polyps), difficult or painful defecation habits in daily life, use of sedatives or analgesics during optical colonoscopy, above average duration of the optical colonoscopy examination, presence of polyps at optical colonoscopy, above average duration of the CT colonography examination, above average amount of CO2 used for colonic distension at CT colonography, and experience parameters on the day of the examination (burdensome bowel preparation for CT colonography or for optical colonoscopy; and pain, embarrassment or discomfort during CT colonography or optical colonoscopy [no, mild and moderate versus severe and extreme burden]). Subsequently, covariates with a p value of 0.10 or lower were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. A stepwise backward selection strategy was used. An odds ratio less than 1 indicates a positive association with a preference for CT colonography; an odds ratio greater than 1 indicates a positive association with a preference for optical colonoscopy.

Results

Study population

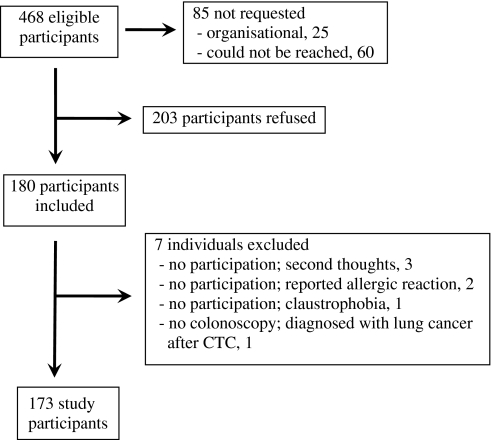

Of 468 eligible individuals scheduled to undergo optical colonoscopy during the inclusion period, 173 participants were included for analysis (Fig. 2, Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Flowchart shows participation of the study population

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Gender | Men | 107 |

| Women | 66 | |

| Age (years) | 56 | |

| Hospital | AMC/OLVG | 122/51 |

| Cultural background | Western | 154 |

| Nonwestern | 14 | |

| Not provided | 5 | |

| Education | Higher vocational/academic | 59 |

| Other | 101 | |

| Not provided | 13 | |

| Income | Above 27,000 € | 56 |

| Below 27,000 € | 77 | |

| Not provided | 40 | |

| Normal bowel habits | At least one defecation per day | 141 |

| At least one defecation per 3 days | 25 | |

| Less than one defecation per 3 days | 3 | |

| Not provided | 4 | |

| Symptoms of CRC | Abdominal pain | 33 |

| Altered bowel habits | 18 | |

| Haematochezia | 10 | |

| Personal history of | Colorectal polyps | 82 |

| Colorectal cancer | 14 | |

| Colorectal polyps and cancer | 22 | |

| Previous optical colonoscopy | Yes | 117 |

| No | 54 | |

| Not provided | 3 |

AMC Academic Medical Center, OLVG Onze Lieve Vrouwe Gasthuis

Bowel preparation, CT colonography and optical colonoscopy procedures

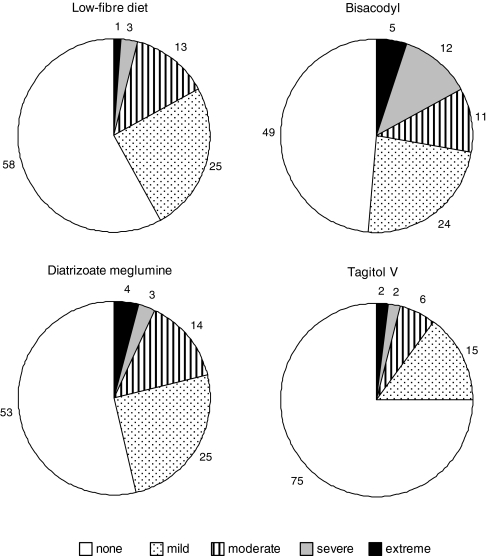

For CT colonography, all participants used the prescribed preparation. Participants rated the use of bisacodyl as the most burdensome factor of the CT colonography preparation (Fig. 3). Side effects such as abdominal pain, diarrhoea and flatulence were reported by 46% (78/171), 94% (158/168) and 42% (72/170) of participants, respectively, and were perceived as severely or extremely burdensome by 23% (18/78), 29% (46/158) and 18% (13/72) (Table 2). Diarrhoea was more burdensome compared with abdominal pain (p = 0.015) and flatulence (p < 0.001), while abdominal pain was more burdensome than flatulence (p = 0.049).

Fig. 3.

Participants’ ratings of the degree of burden for the four different parts of the CT colonography bowel preparation. Tagitol was considered the least burdensome aspect compared with all the others (p < 0.001). Bisacodyl was considered the most burdensome aspect (bisacodyl versus low-fibre diet, p < 0.001; bisacodyl versus diatrizoate meglumine, p = 0.07; bisacodyl versus tagitol V, p < 0.001). Values represent percentages

Table 2.

Side effects of the bowel preparation for CT colonography

| Symptoms reported | None | Mild | Moderate | Severe | Extreme | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdominal pain | Yes | n = 78 | 4/78 (5) | 31/78 (40) | 25/78 (32) | 9/78 (12) | 9/78 (12) |

| No | n = 93 | ||||||

| Diarrhoea | Yes | n = 158 | 15/158 (10) | 52/158 (33) | 45/158 (29) | 26/158 (17) | 20/158 (13) |

| No | n = 0 | ||||||

| Flatulence | Yes | n = 72 | 14/72 (19) | 34/72 (47) | 11/72 (15) | 7/72 (10) | 6/72 (8) |

| No | n = 98 | ||||||

Participants indicated whether they experienced side effects of the bowel preparation for CT colonography. If side effects were present, the burden of the side effect was rated using a five-point scale. Values in parenthesis are percentages

The average time that participants spent in the CT examination room was 21 min (range 13–48). Buscopan was administered to 84% of participants (143/170) and glucagon to 13% (22/170). The average amount of insufflated CO2 was 3.9 l (range 2–8). Most participants (56%; 89/159) found CO2 insufflation the most burdensome aspect of the CT colonography procedure, followed by the breath hold (25%; 39/159).

For optical colonoscopy, an average of 4 l of polyethylene glycol electrolyte solution (PEG) was used (range 2.5–6). The average duration of the optical colonoscopy examination was 40 min (range 12–90). Sedation and/or analgesics were administered to 82% of participants (139/169). In 73% of participants (127/173) a polyp was detected at optical colonoscopy (17). The movement of the scope was the most burdensome aspect of optical colonoscopy (50%; 81/162) followed by the CO2 insufflation (30%; 48/162).

Experience of bowel preparation and procedure (CT colonography versus optical colonoscopy)

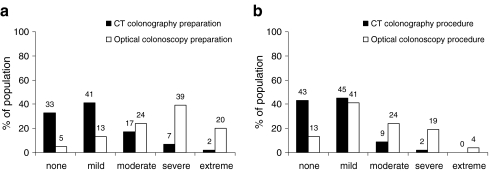

The total burden of the CT colonography preparation was significantly lower than that of the optical colonoscopy preparation (p < 0.001); the CT colonography preparation was considered severe or extreme by 9% (15/171) of participants versus 59% (97/165) for optical colonoscopy (Fig. 4a).

Fig. 4.

Total burden of the bowel preparation (a) and procedure (b). Bowel preparation for optical colonoscopy was considered more burdensome than the bowel preparation for CT colonography (p < 0.001). Optical colonoscopy procedure was more burdensome than the CTC procedure (p < 0.001)

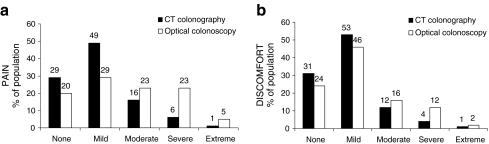

The total burden of the procedure was also significantly lower for CT colonography (Fig. 4b) because participants experienced significantly more pain and discomfort during the optical colonoscopy procedure (all p values < 0.001) (Fig. 5). Embarrassment was rated as none or mild by 97% (166/172) for CT colonography and 93% (154/166) for optical colonoscopy with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.19).

Fig. 5.

Pain and discomfort associated with the examination. Participants experienced more pain and discomfort during the optical colonoscopy examination compared with the CT colonography examination (p < 0.001)

Pre- and post-test appraisal of bowel preparation and procedure

In the pretest (2 weeks earlier at home) and post-test (5 weeks after the examinations at home) appraisals, 94% (152/162) and 87% (144/165) of participants, respectively, indicated that the optical colonoscopy preparation would be or was more burdensome to undergo than the CT colonography preparation. With regard to the examination, 94% (149/159) and 87% (142/164) of participants indicated pre- and post-test that optical colonoscopy was more burdensome than CT colonography. The small shift in the post-test appraisal in favour of optical colonoscopy preparation and procedure was significant (p = 0.003 and p = 0.005, respectively). This is in line with the fact that 18% (30/165) thought CT colonography was more burdensome than anticipated.

Pretest, 57% of participants (90/159) were more reluctant to undergo the optical colonoscopy procedure than the cathartic preparation; post-test, 67% (111/165) actually considered the optical colonoscopy preparation more burdensome than optical colonoscopy itself (p < 0.001). Immediately post-test, the optical colonoscopy preparation was considered the most burdensome event by 57% of participants (84/147); followed by the optical colonoscopy procedure by 35% (52/147), the CTC procedure by 5% (8/147) and last the CTC preparation by 2% (3/147). No significant changes were observed after 5 weeks.

Participants’ preference and determinants of preference

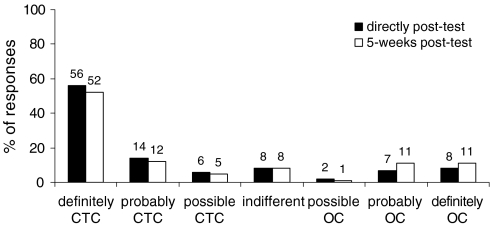

In the recovery room after optical colonoscopy as well as 5 weeks later at home most participants indicated a preference for CT colonography as their next examination (p < 0.001); 76% (124/164) and 69% of participants (115/166), respectively, preferred CT colonography versus 16% (27/164) and 22% of participants (37/166) who preferred optical colonoscopy (Fig. 6). The small shift after 5 weeks towards optical colonoscopy was significant (p = 0.03). Table 3 displays the different reasons the participants gave for their preference.

Fig. 6.

Participant preference directly post-test and 5-weeks post-test. Participants preferred CT colonography above optical colonoscopy as their next examination of choice; as indicated by participants directly after optical colonoscopy (76%) and 5 weeks later at home (69%) (p < 0.001). Values represent percentages

Table 3.

Reasons why participants preferred either CT colonography or optical colonoscopy (5-weeks post-test)

| Preference for CT colonography (n = 115) | Preference for optical colonoscopy (n = 37) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PEG was burdensome | 43 (37%) | OC is therapeutic | 20 (54%) |

| Complete CTC examination (preparation and procedure) less burdensome | 17 (15%) | CTC preparation was burdensome | 6 (16%) |

| CTC preparation less burdensome | 16 (15%) | In the case of a positive CTC then follow-up with OC (2 examinations) | 4 (11%) |

| No sedation for CTC | 7 (6%) | OC is more accurate | 3 (8%) |

| No pain during CTC | 6 (5%) | Discomfort during CTC examination | 1 (3%) |

| Less burden during CTC | 5 (4%) | Sedatives for OC | 1 (3%) |

| Pain during OC | 4 (3%) | Ability to watch screen during OC | 1 (3%) |

| If not necessary no (therapeutic) OC | 3 (3%) | No particular reason | 1 (3%) |

| Simpler preparation for OC | 2 (2%) | ||

| Evaluation of extracolonic condition | 2 (2%) | ||

| No particular reason | 10 (9%) | ||

Participants wrote down on the questionnaire why they preferred CT colonography or optical colonoscopy as their future examination. No list of possible reasons was provided

PEG polyethylene glycol (4 l), CTC computed tomography colonography, OC optical colonoscopy

With regard to associations between preference and patient-related factors, recent symptoms of colorectal cancer was a positive determinant of a preference for optical colonoscopy directly after optical colonoscopy (odds ratio 1.70; p = 0.03), but 5 weeks later at home this association was no longer present (Appendix, Table 5). With regard to participants’ experience parameters, a burdensome bowel preparation for CT colonography (odds ratio 6.06; p = 0.01) and a painful CT colonography procedure (odds ratio 6.34; p = 0.03) were independent determinants of optical colonoscopy preference. Likewise, a burdensome optical colonoscopy preparation (odds ratio 0.40; p = 0.05) and pain at optical colonoscopy (odds ratio 0.10; p = 0.01) were associated with a preference for CT colonography. After 5 weeks, the same determinants of experience were still associated (all p values ≤ 0.04) with the same preference outcome (Appendix, Table 6).

Table 5.

Patient-related determinants of participants’ preference for CTC or OC

| Direct post-test | 5-weeks post-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

| Age ≥ 65 years | 0.13 (0.02–0.97) p = 0.05 | 0.14 (0.02–1.18) p = 0.07 | 1.10 (0.45–2.73) p = 0.83 | NA |

| Female | 0.93 (0.39–2.20) p = 0.87 | NA | 1.28 (0.60–2.71) p = 0.53 | NA |

| High level of education | 2.34 (1.00–5.49) p = 0.05 | 1.92 (0.75–4.90) p = 0.17 | 1.48 (0.69–3.16) p = 0.32 | NA |

| Income ≥ 27,000 euros | 1.02 (0.37–2.80) p = 0.97 | NA | 0.93 (0.40–2.18) p = 0.87 | NA |

| Symptoms of colorectal cancer at present | 1.70 (0.70–4.10) p = 0.03 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) p = 0.03 | 1.02 (1.00–1.04) p = 0.08 | NA |

| Personal history of colorectal polyps | 0.51 (0.22–1.21) p = 0.13 | NA | 0.67 (0.31–1.43) p = 0.30 | NA |

| Personal history of colorectal cancer | 0.89 (0.30–2.59) p = 0.82 | NA | 0.89 (0.34–2.28) p = 0.80 | NA |

| Family history of colorectal polyps or cancer | 2.52 (0.80–7.92) p = 0.11 | NA | 0.91 (0.40–2.06) p = 0.82 | NA |

| Difficult or painful defecation in daily life | 0.27 (0.61–1.23) p = 0.09 | 0.30 (0.07–1.41) p = 0.13 | 0.42 (0.13–1.29) p = 0.13 | NA |

| Use of sedatives or analgesics at optical colonoscopy | 1.20 (0.37–3.82) p = 0.76 | NA | 2.83 (0.67–8.52) p = 0.18 | NA |

| Duration of optical colonoscopy >40 min | 1.02 (0.99–1.05) p = 0.26 | NA | 2.42 (1.12–5.25) p = 0.03 | NA |

| Depiction of polyps at optical colonoscopy | 1.27 (0.47–3.42) p = 0.64 | NA | 0.91 (0.40–2.06) p = 0.82 | NA |

| Duration of CT colonography >20 min | 1.56 (0.66–3.66) p = 0.31 | NA | 1.58 (0.74–3.35) p = 0.24 | NA |

| Insufflation of CO2 at CT colonography (>4 l) | 1.08 (0.46–2.57) p = 0.86 | NA | 0.63 (0.28–1.42) p = 0.26 | NA |

An odds ratio less than 1 indicates a positive association with a preference for CT colonography; an odds ratio greater than 1 indicates a positive association with a preference for optical colonoscopy

NA not applicable

Table 6.

Experience determinants of participants’ preference for CTC or OC

| Direct post-test | 5-weeks post-test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |

| Burdensome bowel preparation for CT colonography | 3.59 (1.16–11.14) p = 0.03 | 6.06 (1.61–22.87) p = 0.01 | 3.533 (1.15–10.87) p = 0.03 | 5.69 (1.51–21.51) p = 0.01 |

| Painful CT colonography examination | 5.13 (1.20–22.01) p = 0.03 | 6.34 (1.23–32.60) p = 0.03 | 12.95 (2.56–65.60) p = 0.01 | 9.80 (1.74–55.08) p = 0.01 |

| Embarrassment experienced during CT colonography | 0.00 (0.00–) p = 1.00 | NA | 0.00 (0.00–) p = 1.00 | NA |

| Discomfort experienced during CT colonography | 0.94 (0.92–8.17) p = 0.94 | NA | 3.29 (0.64–17.08) p = 0.16 | NA |

| Burdensome bowel preparation for optical colonoscopy | 0.42 (0.18–0.98) p = 0.05 | 0.40 (0.16–1.02) p = 0.05 | 0.32 (0.15–0.71) p = 0.01 | 0.31 (0.13–0.77) p = 0.01 |

| Painful optical colonoscopy examination | 0.17 (0.04–0.74) p = 0.02 | 0.10 (0.02–0.58) p = 0.01 | 0.32 (0.12–0.89) p = 0.03 | 0.28 (0.08–0.94) p = 0.04 |

| Embarrassment experienced during optical colonoscopy | 0.00 (0.00–) p = 1.00 | NA | 0.00 (0.00–) p = 0.99 | NA |

| Discomfort experienced during CT optical colonoscopy | 0.18 (0.24–1.43) p = 0.11 | NA | 0.15 (0.02–1.52) p = 0.07 | 0.32 (0.03–3.06) p = 0.32 |

An odds ratio less than 1 indicates a positive association with a preference for CT colonography; an odds ratio greater than 1 indicates a positive association with a preference for optical colonoscopy

NA not applicable

Discussion

In our 5-week follow-up study, most participants (115/166) indicated a preference for CT colonography as their next examination despite the fact that in 20% of CT colonography examinations a referral for optical colonoscopy would still be required for removal of polyps. The cathartic bowel preparation and pain and discomfort experienced during optical colonoscopy were such that optical colonoscopy was considered a more burdensome test than CT colonography with limited preparation.

In accordance with previous studies, we found a better patient tolerance for the limited preparation versus the cathartic preparation [13–16]. However, in our study, almost all participants (158/168) experienced diarrhoea during the CT colonography preparation and this side effect was considered very unpleasant. Although Taylor et al. reported increased defecation frequency in their study [15], in the other studies the occurrence of diarrhoea was not reported or only a few patients experienced diarrhoea [13, 14, 16]. For example, Iannaccone et al. reported that diarrhoea occurred in just 6% of participants (13/203) [16]. This is worth mentioning, because the use of iodinated contrast agents and/or added laxatives is generally associated with diarrhoea [19]. In the study by Iannaccone a higher dose of diatrizoate meglumine (200 ml with a concentration of 370 mg/ml) was used than in our study (180 ml with a concentration of 200 mg/ml), but no additional laxative was applied [16]. At present, we no longer add laxatives to the preparation and we have reduced the dose of iodinated contrast. Patients still experience diarrhoea, but the burden of diarrhoea is significantly improved and image quality has not been impaired [unpublished data]. Despite the occurrence of side effects in our study, the preparation for CT colonography was nonetheless significantly better tolerated than the preparation for optical colonoscopy.

With regard to the CT colonography examination, the insufflation of the colon with CO2 was considered the most burdensome part. This is in line with a previous study that showed that insufflation of air and the insertion of the inflexible rectal tube were the most burdensome aspects [13]. Insertion of a rectal tube was not considered burdensome because we used a thin flexible catheter. Although in our study several aspects of the CTC examination were rated severely or extremely burdensome by some participants, the complete procedure was considered severely burdensome by only 2% (4/173) and none of the participants considered the examination extremely burdensome. In comparison, significantly more participants, 23% (38/166), perceived the optical colonoscopy examination as severely or extremely burdensome (p < 0.001).

Five weeks after completing both tests, 69% of participants preferred CT colonography and 22% preferred optical colonoscopy. In an earlier acceptance study comparing cathartic CT colonography with optical colonoscopy, 61% of participants preferred CT colonography [6]. The observed increase of 8% was not as large as we had anticipated, probably because most participants had diarrhoea as a side effect. This is underlined by the fact that a burdensome CT colonography preparation was associated with a preference for optical colonoscopy (p = 0.01). However, the decisive factor for most participants in preferring optical colonoscopy was the therapeutic aspect. As this is an important benefit of optical colonoscopy, it is a detriment of limited CT colonography (in comparison to cathartic CT colonography) because same-day referral for therapeutic optical colonoscopy is not possible.

Some limitations of our study should be discussed. First, the bowel preparation for optical colonoscopy comprised the standard 4 l of polyethylene glycol solution (PEG) (KleanPrep; Norgine Ltd; Harfield, UK) [20, 21]. However, 2 l of PEG (Moviprep; Norgine Ltd; Harfield, UK) or sodium phosphate can prepare the colon as effectively [22–24], although the latter cannot be used in patients with heart and kidney failure [25, 26]. Preference outcome might have shifted towards optical colonoscopy if a milder preparation had been used for optical colonoscopy. A second potential limitation is that participants were told that the accuracy of CT colonography and optical colonoscopy with limited preparation were comparable [16]. It is likely that better accuracy for optical colonoscopy might move the preference pattern towards optical colonoscopy [27]. Third, the fact that only participants were included who were willing to undergo CT colonography in addition to their scheduled optical colonoscopy might have influenced our results in favour of CT colonography. Fourth, a surveillance population of individuals at increased risk was investigated and therefore we cannot be certain if our data are applicable to a screening population at average risk. However, as the referral rate for optical colonoscopy in a screening setting would probably be lower than the indicated 20% in our study, we believe that the reported preference for CT colonography could be an underestimation. Finally, no randomised comparison was made between noncathartic and cathartic CT colonography. However, as the PEG preparation for optical colonoscopy is also widely used for cathartic CT colonography, we believe that a limited preparation will be preferred above a PEG preparation for CT colonography.

Conclusion

This prospective study investigated individual experience of and preference for CT colonography with a limited preparation more stringently than previous studies. Our results demonstrated that the occurrence of diarrhoea was frequent and considered a burdensome side effect of the CT colonography preparation. To optimise patient acceptance, further efforts should be made to reduce this side effect. CT colonography, however, was better tolerated by participants than optical colonoscopy with regard to both preparation and procedure. As such, an apparent preference for CT colonography was observed in this population of individuals at increased risk of colorectal cancer. Therefore, we believe that CT colonography with a limited bowel preparation can be of value in increasing participation rates in screening programmes for colorectal cancer.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Marjolein Liedenbaum and Christina Lavini for their critical review of this manuscript. This research was supported by a grant from the Commission on Applied Clinical Research of the Dutch Cancer Society (KWF).

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Appendix

References

- 1.Johnson CD, Chen MH, Toledano AY, et al. Accuracy of CT colonography for detection of large adenomas and cancers. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1207–1217. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0800996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim DH, Pickhardt PJ, Taylor AJ, et al. CT colonography versus colonoscopy for the detection of advanced neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1403–1412. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2009: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:27–41. doi: 10.3322/caac.20008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson N. Virtual colonoscopy accepted as primary colon cancer screening Test. JNCI. 2008;100:1492–1494. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ristvedt SL, McFarland EG, Weinstock LB, Thyssen EP. Patient preferences for CT colonography, conventional colonoscopy, and bowel preparation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:578–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Gelder RE, Birnie E, Florie J, et al. CT colonography and colonoscopy: assessment of patient preference in a 5-week follow-up study. Radiology. 2004;233:328–337. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2331031208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beebe TJ, Johnson CD, Stoner SM, Anderson KJ, Limburg PJ. Assessing attitudes toward laxative preparation in colorectal cancer screening and effects on future testing: potential receptivity to computed tomographic colonography. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:666–671. doi: 10.4065/82.6.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Callstrom MR, Johnson CD, Fletcher JG, et al. CT colonography without cathartic group: feasibility study. Radiology. 2001;219:693–698. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.3.r01jn22693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lefere P, Gryspeerdt S, Marrannes J, et al. CT colonography after fecal tagging with a reduced cathartic cleansing and a reduced volume of barium. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:1836–1842. doi: 10.2214/ajr.184.6.01841836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thomeer M, Carbone I, Bosmans H, et al. Stool tagging applied in thin-slice multidetector computed tomography colonography. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:132–139. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bielen D, Thomeer M, Vanbeckevoort D, et al. Dry group for virtual CT colonography with fecal tagging using water-soluble contrast medium initial results. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:453–458. doi: 10.1007/s00330-002-1755-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensch S, de Vries AH, Pot D, et al. Image quality and patient acceptance of four regimens with different amounts of mild laxatives for CT colonography. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;191:158–167. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lefere PA, Gryspeerdt SS, Dewyspelaere J, et al. Dietary fecal tagging as a cleansing method before CT colonography: initial results polyp detection and patient acceptance. Radiology. 2002;224:393–403. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2241011222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zalis ME, Perumpillichira JJ, Magee C, Kohlberg G, Hahn PF. Tagging-based, electronically cleansed CT colonography: evaluation of patient comfort and image readability. Radiology. 2006;239:149–159. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2383041308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor SA, Slater A, Burling DN, et al. CT colonography: optimisation, diagnostic performance and patient acceptability of reduced-laxative regimens using barium-based faecal tagging. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:32–42. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0631-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iannaccone R, Laghi A, Catalano C, et al. Computed tomographic colonography without cathartic group for the detection of colorectal polyps. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:300–1311. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jensch S, de Vries AH, Peringa J, et al. CT colonography with limited bowel preparation: performance characteristics in an increased-risk population. Radiology. 2008;247:122–132. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2471070439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Florie J, Jensch S, Nievelstein RA, et al. MR colonography with limited bowel preparation compared with optical colonoscopy in patients at increased risk for colorectal cancer. Radiology. 2007;243:122–131. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431052088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pickhardt PJ. CT Colonography without catharsis: the ultimate study or useful additional option? Gastroenterology. 2005;128:521–522. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis GS, Santa Ana CA, Morawski SG, Fordtran JS. Development of a lavage solution associated with minimal water and electrolyte absorption or secretion. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:991–995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ell C, Fischbach W, Keller R, et al. A randomized, blinded, prospective trial to compare the safety and efficacy of three bowel-cleansing solutions for colonoscopy. Endoscopy. 2003;35:300–304. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bitoun A, Ponchon T, Barthet M, et al. Results of a prospective randomised multicentre controlled trial comparing a new 2-L ascorbic acid plus polyethylene glycol and electrolyte solution vs. sodium phosphate solution in patients undergoing elective colonoscopy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;24:1631–1642. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.03167.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poon CM, Lee DW, Mak SK, et al. Two liters of polyethylene glycol-electrolyte lavage solution versus sodium phosphate as bowel cleansing regimen for colonoscopy: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Endoscopy. 2002;34:560–563. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-33207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ginnerup Pedersen B, Møller Christiansen TE, Viborg Mortensen F, Christensen H, Laurberg S. Bowel cleansing methods prior to CT colonography. Acta Radiol. 2002;43:306–311. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0455.2002.430312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Curran MP, Plosker GL. Oral sodium phosphate solution: a review of its use as a colorectal cleanser. Drugs. 2004;64:1697–1714. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tan HL, Liew QY, Loo S, Hawkins R. Severe hyperphosphataemia and associated electrolyte and metabolic derangement following the administration of sodium phosphate for bowel preparation. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:478–483. doi: 10.1046/j.0003-2409.2001.02519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.von Wagner C, Halligan S, Atkin WS, et al. Choosing between CT colonography and colonoscopy in the diagnostic context: a qualitative study of influences on patient preferences. Health Expect. 2009;12:18–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00520.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]