Abstract

We analyzed the performance of Amplicor for detecting carcinogenic human papillomavirus infections and cervical precancer in women with an atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) Pap and compared the results to Hybrid Capture 2 (hc2) in the ASCUS and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) triage study (ALTS). Baseline specimens collected from women referred into ALTS based on an ASCUS Pap result were prospectively tested by hc2 and retrospectively tested by Amplicor (n=3,277). Following receiver-operator-characteristics curve analysis, Amplicor performance was analyzed at three cutoffs (0.2; 1.0; 1.5). Paired Amplicor and hc2 results were compared for the detection of 2-year cumulative cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) grade 3 and more severe disease outcomes (CIN3+) and for the detection of 13 targeted carcinogenic HPV types. Amplicor at the 0.2 cutoff had a higher sensitivity for the detection of CIN3+ (95.8% vs 92.6%, p=0.01) but a much lower specificity (38.9% vs. 50.6%, p<0.001) than hc2. Amplicor at the 1.5 cutoff had an identical sensitivity for the detection of CIN3+ (92.6%) and a slightly lower specificity (47.5%), p<0.001). The positive predictive value of hc2 was higher at all Amplicor cutoffs, while referral rates were significantly lower (53.2% for hc2 vs. 64.1% at the 0.2 cutoff and 56.0% at the 1.5 cutoff, p<0.001). Amplicor was more analytically specific for detecting targeted carcinogenic HPV types than hc2. Amplicor at the 1.5 cutoff had comparable performance to hc2. While Amplicor missed more disease related to non-targeted types, hc2 was more likely to miss disease related to targeted types.

Keywords: cervical cancer, human papillomavirus (HPV), screening, atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS), triage, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN)

Introduction

About 15 genotypes of the human papillomaviruses (HPV) are associated with the development of cervical cancer and its immediate precursor, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 [CIN3] and carcinoma in situ [CIS]). While the vast majority of women are supposedly infected with HPV during their lifetime, only a small percentage of these women will develop a CIN3/CIS (1) and only a fraction of those become invasive cancer (2;3).

Currently, screening for cervical cancer and its precursors is primarily based on cytology. A major limitation of cytological screening is the low sensitivity of a single test, making repeated, regular screening at 1- to 2-year intervals necessary. Most non-normal screening results include low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL) and atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance (ASCUS) (4). While these abnormalities are typically cytomorphological manifestations of innocuous, transient HPV infections, in 10–15% of women these cytologic changes are accompanied by an underlying histologic precancer (CIN3/CIS) (5;6). In fact, in absolute numbers, most precancers, including CIN2, are found at workup triggered by ASCUS and LSIL (versus high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions [HSIL]) (7). Therefore, LSIL and ASCUS cytology results require further diagnostic investigation to avoid missing high-grade disease.

Based on the central role of persistent, carcinogenic human papillomavirus (HPV) in cervical carcinogenesis, carcinogenic HPV testing has recently been introduced into cervical cancer screening. Carcinogenic HPV testing has proven greater reproducibility (8;9) and greater sensitivity for detection of cervical precancer (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 [CIN3]) and cancer (together, abbreviated here as ≥CIN3) (10–14) than cytology. Recent ASCCP guidelines approve the use of carcinogenic HPV testing for triage of women with ASC-US, adjunct testing with cytology in primary screening for women age 30 and older, post-colposcopy follow-up, and post-treatment monitoring (15). Currently, there is only one FDA-approved HPV detection assay, the Hybrid Capture 2 (hc2; Qiagen, Gaithersburg, MD) test. Hybrid Capture 2 uses RNA-DNA hybridization and signal amplification to detect the presence of any of 13 carcinogenic types (HPV16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, and 68) in aggregate; hc2 also cross-reacts with some untargeted, mostly non-carcinogenic HPV genotypes, especially HPV53, 67, 70, 82 and HPV66 (16), the latter of which has been recently reclassified as carcinogenic (17).

However, other tests are being developed and need to be evaluated for their clinical utility. One such test, the Amplicor HPV test (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), is a PCR-based assay that targets the same 13 carcinogenic genotypes as hc2. After amplification of a sequence in the HPV L1 gene, labeled probes are hybridized to the amplified DNA and the optical density (OD) is measured. Despite the use of Amplicor in several studies (18–23), there has been no formal, independent evaluation of Amplicor cutoffs for detecting the presence of a carcinogenic genotype (analytical sensitivity) or the presence or risk of cervical precancer (clinical sensitivity).

The aim of this study was to formally evaluate cutoff levels for Amplicor positivity and to analyze the analytic and clinical performance of Amplicor in detecting carcinogenic HPV and related disease within the ASCUS-LSIL triage study (ALTS).

Subjects and Methods

Study design and population

ALTS was a multi-center, randomized trial conducted by the National Cancer Institute (National Institutes of Health, Rockville, MD) comparing three management strategies for women with ASCUS (n=3488) or LSIL (n=1572) cytology (referral cytology before revision of the Bethesda terminology). Women were either managed with immediate colposcopy (IC arm, referral regardless of test results), HPV triage (HPV arm, referral to colposcopy if enrollment hc2 result was positive or missing, or, for patients’ safety, if the enrollment cytology result was HSIL), or by conservative management (referral to colposcopy only if enrollment cytology result was HSIL). During the two-year follow-up, women in the three arms of the study were re-evaluated by cytology every 6 months and sent to colposcopy if cytology was called HSIL by the clinical center pathologists.

At all visits, women received a pelvic exam and two cervical specimens were collected, one into PreservCyt (Cytyc, Marlborough, MA) for cytology and hc2 testing and a second cervical specimen into specimen transport medium (STM; Qiagen). The National Cancer Institute and local institutional review boards approved the study and all participants provided written informed consent. This analysis was restricted to women referred for an ASCUS Pap.

HPV DNA testing

During ALTS, residual PreservCyt specimens were tested by hc2 according to the manufacturer’s instructions, defining hc2 signal strength by relative light units/positive control (RLU/CO).

Amplicor testing was done on archived aliquots of the enrollment STM specimens according to manufacturer’s specifications for women referred into ALTS for an ASCUS Pap smear. One-hundred microliter STM aliquots were subjected to automated sample preparation for DNA extraction of up to 96 specimens at a time on the Qiagen MDx platform (using the MinElute media MDx kit and manufacturer’s instructions).

HPV genotyping data was obtained using two methods, the Line Blot Assay (LBA) and the commercialized version of LBA, Linear Array (LA). Both are L1 consensus primer-based PCR assays using PGMY09/11 primers. LBA was performed on the STM specimens as previously described (24–26) for 27 or 38 HPV genotypes, including the 13 carcinogenic HPV genotypes targeted by hc2 and Amplicor as well as the untargeted HPV genotypes with which hc2 is most likely to cross-react. Aliquots of the archived enrollment STM specimens from women referred into ALTS because of ASCUS were retested using LA, which tests for 37 of the 38 HPV genotypes detected by LBA, excluding HPV57, as previously described (27). LA was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions in the product insert, except that an automated sample preparation for DNA extraction was used as described above for Amplicor.

Pathology and treatment

Clinical management was based on the clinical center pathologists’ (CC pathology) cytologic interpretations and histologic diagnoses as previously described (5;6;28;29). Referral smears, ThinPreps, and histology slides were also sent to the Pathology Quality Control Group (QC Pathology) based at the Johns Hopkins Hospital for review, including computer-assisted review, and secondary diagnoses as previously described (5;6;28;29). Women with a CC diagnosis of CIN2 or more severe (CIN2+) or a QC diagnosis of CIN3 or more severe (CIN3+) were offered excisional treatment by loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP). In addition, all women with persistent mild abnormalities (e.g., LSIL or carcinogenic HPV-positive ASCUS) at the time of exit from the study were also offered LEEP.

Statistical analysis

Of the 3,488 women referred into ALTS because of an ASCUS Pap, 3,442 (98.7%) had Amplicor results, 3,326 (95.4%) had hc2 results, and 3,277 (94.0%) had both hc2 and Amplicor results, constituting the analysis population. There were no differences in the frequencies by study arm, colposcopy at enrollment, QC-referral cytology, QC-enrollment cytology, and HPV risk groups between the women included in the analysis (n=3277) and those excluded due to missing test results (n=211). There were minor differences of enrollment at study centers (Oklahoma: 7.6% vs. 14.2%, respectively, and Pennsylvania: 25.6% and 19.3%, respectively, p=0.02) between women included and excluded from the study. Among the women included in this analysis, 3,167/3,277 (96.6%) had LBA results, 3,277/3,277 (100%) had LA results, and 3,167/3,277 (96.6%) had LBA or LA results for detection of individual HPV genotypes.

Unlike hc2, Amplicor has an internal control based on the amplification of the β-globin gene. Since Amplicor sample adequacy is defined by both the β-globin and the HPV optical density (OD), sample adequacy was affected when both cutoffs were altered. In all women referred for ASCUS cytology that were tested for Amplicor, 3421 of 3442 (99.4%) specimens had a β-globin cutoff ≥0.2 and 3,277 of 3,442 (95.2%) specimens had a β-globin cutoff ≥1.0. To analyze whether the different β-globin cutoff levels influenced the clinical performance, we compared ROC curves based on HPV cutoffs for the detection of QC CIN3+ in the complete study at both β-globin cutoffs. Both curves had identical shapes, indicating that there was no difference in performance characteristics between a 0.2 and 1.0 globin cutoff (data not shown). In agreement with previous studies, we used a 0.2 cutoff for β-globin positivity in the subsequent analyses.

ROC curve analysis was performed for Amplicor by calculating the sensitivity and 1-specificity for detecting 2-year cumulative CIN3+ as diagnosed by QC Pathology in all study arms at 17 cutpoints (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 1.25, 1.5, 1.75, 2.0, 2.25, 2.5, 2.75, 3.0, and 10.0). Youden’s index (YI) was calculated as sensitivity+specificity-1. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), NPV, and YI were calculated using Amplicor cutpoints of 0.2, 1.0, and 1.5 for the following endpoints: QC Pathology-diagnosed 2-year cumulative CIN3+, CC Pathology-diagnosed 2-year cumulative CIN2+, QC Pathology-diagnosed CIN3+ at enrollment among women in the IC arm, and CC Pathology-diagnosed CIN2+ at enrollment among women in the IC arm. The Amplicor results were compared between different cutpoints and to hc2 results as the reference standard. Differences in test positivity (referral rate), test sensitivity and specificity for CIN3+ and CIN2+ were tested for statistical significance using an exact McNemar’s χ2. Differences in PPV and NPV were tested for statistical significance according to method developed by Leisenring and Pepe (30).

Detection of carcinogenic HPV by LA and hc2 was compared by calculating κ values and percent total agreement. Differences in detection were tested for statistical significance using an exact McNemar’s χ2. Paired results were stratified by enrollment ThinPrep cytology results (ASC-US, LSIL, ASC-H, HSIL, according to the revised Bethesda terminology) as rendered by CC pathology. They were also stratified using a priori established HPV categorization according to cervical cancer risk based on the detection of these types by LBA or LA: (1) positive for HPV16; (2) else positive for HPV18; (3) else positive for any carcinogenic HPV genotype and negative for HPV16 and HPV18 (HR11); (4) else positive for any non-carcinogenic HPV genotypes and negative for all carcinogenic genotypes; or (5) PCR negative (HPV16>HPV18> carcinogenic HPV exc. HPV16 & HPV18>non-carcinogenic HPV>PCR negative). In the case of multi-type infections, the result was assigned to the highest risk category.

We also compared the percent positive tests for hc2 and Amplicor at the 0.2 and 1.5 cutpoint for a second hierarchical classification of HPV risk groups (HPV16 > HPV18, other carcinogenic types (HR11) > HPV66 > HPV53/67/70/82 > other HPV) which included additional categories for untargeted HPV genotypes commonly detected by hc2, to compare and contrast the analytic specificity of the two assays. Significance testing was based on Pearson χ2 test. All statistical tests were two-sided and considered to be significant at p<0.05. Bonferroni’s correction was used to adjust for multiple statistical testing in comparing the clinical performance and the HPV detection at different Amplicor cutoffs. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Analysis of Amplicor cutoffs

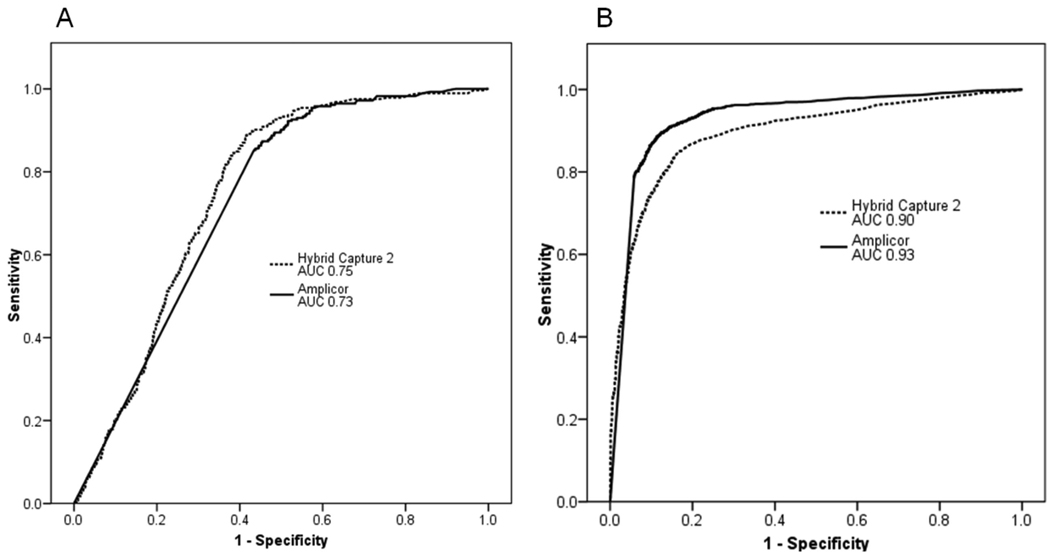

We analyzed the HPV cutoffs and computed Youden’s index for every cutpoint analyzed to identify optimal tradeoffs between sensitivity and specificity for CIN3+ detection at a minimum sensitivity of 90% or greater. In that region, ROC analysis showed a flat curve and did not reveal a clear cutoff value (Figure 1A). In agreement with those data, the Youden’s index (YI) versus cutpoint plot did not show any distinguishing peaks for YI, except for a slight elevation at the 1.5 cutpoint (YI = 0.4) (not shown). Previous studies have used the 0.2 cutoff, which showed one of the lowest YIs in our analysis (YI = 0.35). Based on this analysis and the previously published literature, we decided to evaluate 3 OD cutpoints (0.2, 1.0, and 1.5) for their analytical and clinical performance of Amplicor in ALTS. Similarly, we analyzed Amplicor HPV cutoffs to detect the 13 targeted carcinogenic types as detected by LBA or LA. The ROC curve showed a greater area under the curve for carcinogenic HPV than for CIN3+ detection, suggesting that Amplicor better discriminates between carcinogenic HPV DNA positive versus negative than between 2-year cumulative CIN3+ vs. <CIN3+ (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Clinical and analytical performance of Amplicor and Hybrid Capture 2 (hc2) analyzed in Receiver-Operator-Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis with areas under the curve (AUC) calculation to detect 2-year cumulative cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe (CIN3+) cases as diagnosed by quality control pathology (1A) and 13 targeted carcinogenic HPV genotypes as detected by defined by Linear Array (LA) and/or Line Blot Assay (LBA) (1B).

Clinical performance of Amplicor HPV detection

Using QC Pathology-diagnosed 2-year cumulative CIN3+ as our primary endpoint, we compared the clinical performance of Amplicor at 3 cutpoints (0.2, 1.0, and 1.5) and hc2 (Table 1). As the cutoff value for Amplicor was changed from 0.2 to 1.0 to 1.5, sensitivity changed from 95.8% to 93.3% to 92.6%, respectively. Accordingly, specificity changed from 38.9% to 44.6% to 47.5% at the three cutoffs, respectively. By comparison, hc2 had a sensitivity of 92.6% and a specificity of 50.6%. The difference in sensitivity between Amplicor and hc2 was only significant at the 0.2 cutoff, while Amplicor was less specific than hc2 at all cutpoints.

Table 1.

Clinical performance of carcinogenic HPV detection by Amplicor and Hybrid Capture 2 (hc2) for 2-year cumulative cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe (CIN3+) as diagnosed by quality control pathology and 2-year cumulative CIN2+diagnosed by clinical center pathology (n=3,286) as well as restricted to the IC arm (n=1,081) in women referred into ALTS for an atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASCUS) Pap.

| All study arms, Outcome=QC-CIN3+ (n=235) | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Sens (%) |

(CI) | p | Spec (%) |

(CI) | p | PPV (%) |

(CI) | p | NPV (%) | (CI) | p | Youden | Referral (%) |

p | Invalid | N |

| Amplicor 0.2 | 95.8 | (92.8–97.8) | 0.01 | 38.9 | (37.1–40.6) | <0.001 | 13.0 | (11.6–14.5) | <0.001 | 98.98 | (98.22–99.47) | 0.13 | 34.7 | 64.1 | <0.001 | 9 | 3277 |

| Amplicor 1.0 | 93.3 | (89.8–95.9) | 0.80 | 44.6 | (42.8–46.4) | <0.001 | 13.8 | (12.3–15.4) | <0.001 | 98.59 | (97.81–99.15) | 0.89 | 37.9 | 58.7 | <0.001 | 9 | 3277 |

| Amplicor 1.5 | 92.6 | (89.0–95.4) | 1.00 | 47.5 | (45.7–49.3) | <0.001 | 14.4 | (12.8–16.1) | 0.007 | 98.54 | (97.78–99.10) | 0.74 | 40.2 | 56.0 | <0.001 | 9 | 3277 |

| hc2 | 92.6 | (89.0–95.4) | Ref | 50.6 | (48.8–52.4) | Ref | 15.1 | (13.5–16.9) | Ref | 98.64 | (97.92–99.15) | Ref | 43.2 | 53.2 | Ref | . | 3286 |

| All study arms, Outcome=CC–CIN2+ (n=399) | |||||||||||||||||

| Test |

Sens (%) |

(CI) | p |

Spec (%) |

(CI) | p |

PPV (%) |

(CI) | p | NPV (%) | (CI) | p | Youden |

Referral (%) |

p | Invalid | N |

| Amplicor 0.2 | 93.0 | (90.4–95.1) | 0.12 | 41.1 | (39.2–42.9) | <0.001 | 22.1 | (20.4–24.0) | <0.001 | 97.02 | (95.88–97.92) | 0.77 | 34.05 | 64.1 | <0.001 | 9 | 3277 |

| Amplicor 1.0 | 90.6 | (87.7–93.0) | 0.74 | 47.0 | (45.1–48.9) | <0.001 | 23.5 | (21.7–25.5) | <0.001 | 96.52 | (95.40–97.43) | 0.15 | 37.59 | 58.7 | <0.001 | 9 | 3277 |

| Amplicor 1.5 | 89.4 | (86.4–92.0) | 0.20 | 50.1 | (48.2–51.9) | <0.001 | 24.4 | (22.4–26.4) | <0.001 | 96.33 | (95.22–97.24) | 0.05 | 39.45 | 56.0 | <0.001 | 9 | 3277 |

| hc2 | 91.0 | (88.2–93.4) | Ref | 53.7 | (51.8–55.5) | Ref | 26.2 | (24.1–28.3) | Ref | 97.08 | (96.11–97.86) | Ref | 44.7 | 53.2 | Ref | . | 3286 |

| Immediate colposcopy arm, Outcome=QC–CIN3+ (n=57) | |||||||||||||||||

| Test |

Sens (%) |

(CI) | p |

Spec (%) |

(CI) | p |

PPV (%) |

(CI) | p | NPV (%) | (CI) | p | Youden |

Referral (%) |

p | Invalid | N |

| Amplicor 0.2 | 92.7 | (82.4–98.0) | 0.06 | 36.2 | (33.3–39.3) | <0.001 | 7.2 | (5.4–9.4) | 0.0006 | 98.93 | (97.29–99.71) | 0.24 | 29.0 | 65.2 | <0.001 | 2 | 1079 |

| Amplicor 1.0 | 92.7 | (82.4–98.0) | 0.38 | 41.6 | (38.6–44.7) | <0.001 | 7.9 | (5.9–10.2) | 0.049* | 99.07 | (97.64–99.75) | 0.48 | 34.3 | 60.1 | <0.001 | 2 | 1079 |

| Amplicor 1.5 | 90.9 | (80.1–97.0) | 0.63 | 44.6 | (41.6–47.7) | 0.038* | 8.1 | (6.1–10.5) | 0.35 | 98.92 | (97.49–99.65) | 0.53 | 35.5 | 57.2 | 0.03* | 2 | 1079 |

| hc2 | 90.9 | (80.1–97.0) | Ref | 48.0 | (44.9–51.1) | Ref | 8.6 | (6.4–11.1) | Ref | 98.99 | (97.67–99.67) | Ref | 38.9 | 54.0 | Ref | . | 1081 |

| Immediate colposcopy arm, Outcome=CC–CIN2+ (n=115) | |||||||||||||||||

| Test |

Sens (%) |

(CI) | p |

Spec (%) |

(CI) | p |

PPV (%) |

(CI) | p | NPV (%) | (CI) | p | Youden |

Referral (%) |

p | Invalid | N |

| Amplicor 0.2 | 91.7 | (84.9–96.2) | 0.23 | 37.7 | (34.7–40.9) | <0.001 | 14.2 | (11.7–17.0) | <0.001 | 97.60 | (95.49–98.90) | 0.91 | 29.5 | 65.2 | <0.001 | 2 | 1079 |

| Amplicor 1.0 | 89.0 | (81.6–94.2) | 1.00 | 43.1 | (40.0–46.3) | <0.001 | 15.0 | (12.3–17.9) | 0.0010 | 97.21 | (95.18–98.55) | 0.57 | 32.1 | 60.1 | <0.001 | 2 | 1079 |

| Amplicor 1.5 | 88.1 | (80.5–93.5) | 1.00 | 46.3 | (43.1–49.5) | 0.019* | 15.6 | (12.8–18.7) | 0.042* | 97.19 | (95.24–98.49) | 0.50 | 34.4 | 57.2 | 0.03* | 2 | 1079 |

| hc2 | 89.9 | (82.7–94.9) | Ref | 50.0 | (46.8–53.2) | Ref | 16.8 | (13.8–20.1) | Ref | 97.79 | (96.07–98.89) | Ref | 39.9 | 54.0 | Ref | . | 1081 |

Sens= Sensitivity; Spec= Specificity; PPV= Positive predictive value; NPV= Negative predictive value; CI= 95% confidence interval. Invalid indicates samples with a globin results below 0.2 and an HPV result below the respective cutoff. Differences in sensitivity, specificity, and referral were tested for statistical significance using an exact McNemar’s χ2 test. Differences in PPV and NPV were determined by a method developed by Leisenring and Pepe (30).

An indicates that the result was not significant after correction for multiple testing.

The positive predictive value (PPV) of Amplicor was 13.0% at the 0.2 cutpoint, 13.8% at the 1.0 cutpoint, and 14.4% at the 1.5 cutpoint. All were significantly less than the 15.1% PPV for hc2. The negative predictive value (NPV) of Amplicor was 99.98% at the 0.2 cutpoint, 98.59% at the 1.0 cutpoint, and 98.54% at the 1.5 cutpoint. These NPVs were not significantly different than a NPV of 98.64% for hc2.

At the 0.2 cutpoint, Amplicor had a referral rate of 64.1% that was reduced to 58.7% and 56.0% at the 1.0 and 1.5 cutpoints, respectively, but all referral rates were still significantly higher than the referral rate of 53.2% for hc2 (p<0.001 for all cutpoints).

We extended our analysis to the clinical center diagnosis of CIN2+ as a less strict outcome and restricted it to the immediate colposcopy arm. These modified endpoints yielded very similar results. Most importantly, neither assay showed qualitative differences at the different endpoints; all performance measures changed in the same direction and order of magnitude. Youden’s index, a measurement of test accuracy, was higher at all hc2 cutoffs as compared to Amplicor.

Agreement between hc2 and Amplicor

At the 0.2 cutoff, 2,102 of 3,277 (64.1%) specimens tested positive by Amplicor, while 1,742 (53.2%) tested positive by hc2 (p<0.001). At the higher 1.5 cutoff, 1,834 (56.0%) specimens still tested positive by Amplicor, which was still greater than hc2 (p<0.001). The overall agreement between hc2 and Amplicor was 78.0% (kappa = 0.55) at the 0.2 Amplicor cutoff and 80.6% (kappa = 0.61) at the 1.5 Amplicor cutoff.

At all cutoffs, Amplicor had a higher sensitivity to detect infections by HPV16, HPV18, and all other targeted carcinogenic types combined (p < 0.001), while non-targeted non-carcinogenic types were more frequently detected by hc2 than Amplicor at the 0.2 cutpoint (p = 0.03) and at the 1.5 cutpoint (p < 0.001) (Table 2). Among women with LSIL cytology, hc2 was more likely to test positive than Amplicor at either the 0.2 or the 1.5 cutpoint (p < 0.001). Stratification of the LSIL group by HPV risk groups showed that the discordance between hc2 and Amplicor was the result of more non-carcinogenic HPV-positive infections testing positive by hc2 than Amplicor (data not shown). Overall, a very high agreement between Amplicor and hc2 was observed for the HSIL cytology group at both Amplicor cutoffs (97.2% at the 0.2 cutoff and 94.9% at the 1.5 cutoff, respectively).

Table 2.

Comparison of and agreement between Amplicor and hc2 for the detection of carcinogenic HPV for all paired tests stratified by the enrollment cytology result and HPV risk group as detected by Linear Array (LA) and/or Line Blot Assay (LBA) for women referred into ALTS for an atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASCUS) Pap at two Amplicor cutoffs (0.2 and 1.5)

| AMP 0.2/hc2, Cytology stratification | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | N | hc2+ (%) | Amp+ (%) | hc2+/AMP+ (%) | hc2+/AMP− (%) | hc2-/AMP+ (%) | hc2-/AMP− (%) | Kappa | Agreement (%) | p |

| All | 3,277 | 1,742 (53.16) | 2,102 (64.14) | 1,561 (47.64) | 181 (5.52) | 541 (16.51) | 994 (30.33) | 0.55 | 77.97 | <0.001 |

| ASC-US | 819 | 455 (55.56) | 534 (65.20) | 408 (49.82) | 47 (5.74) | 126 (15.38) | 238 (29.06) | 0.56 | 78.88 | <0.001 |

| LSIL | 576 | 530 (92.01) | 501 (86.98) | 485 (84.20) | 45 (7.81) | 16 (2.78) | 30 (5.21) | 0.44 | 89.41 | <0.001 |

| ASC-H | 128 | 104 (81.25) | 107 (83.59) | 97 (75.78) | 7 (5.47) | 10 (7.81) | 14 (10.94) | 0.54 | 86.72 | 0.47 |

| HSIL | 176 | 171 (97.16) | 172 (97.73) | 169 (96.02) | 2 (1.14) | 3 (1.70) | 2 (1.14) | 0.43 | 97.16 | 0.65 |

| AMP 0.2/hc2, HPV stratification | ||||||||||

| Group | N | hc2+ (%) | Amp+ (%) | hc2+/AMP+ (%) | hc2+/AMP− (%) | hc2-/AMP+ (%) | hc2-/AMP− (%) | Kappa | Agreement (%) | p |

| HPV16 | 577 | 501 (86.83) | 549 (95.15) | 496 (85.96) | 5 (0.87) | 53 (9.19) | 23 (3.99) | 0.40 | 89.95 | <0.001 |

| HPV18 | 160 | 124 (77.50) | 152 (95.00) | 121 (75.63) | 3 (1.88) | 31 (19.38) | 5 (3.13) | 0.16 | 78.75 | <0.001 |

| HR11 | 1056 | 842 (79.73) | 997 (94.41) | 831 (78.69) | 11 (1.04) | 166 (15.72) | 48 (4.55) | 0.29 | 83.24 | <0.001 |

| NonHR | 476 | 151 (31.72) | 120 (25.21) | 40 (8.40) | 111 (23.32) | 80 (16.81) | 245 (51.47) | 0.02 | 59.87 | 0.025 |

| Neg | 898 | 51 (5.68) | 206 (22.94) | 9 (1.00) | 42 (4.68) | 197 (21.94) | 650 (72.38) | −0.02 | 73.39 | <0.001 |

| AMP 1.5/hc2, Cytology stratification | ||||||||||

| Group | N | hc2+ (%) | Amp+ (%) | hc2+/AMP+ (%) | hc2+/AMP− (%) | hc2-/AMP+ (%) | hc2-/AMP− (%) | Kappa | Agreement (%) | p |

| All | 3,277 | 1742 (53.16) | 1,834 (55.97) | 1,470 (44.86) | 272 (8.30) | 364 (11.11) | 1171 (35.73) | 0.61 | 80.59 | <0.001 |

| ASC-US | 819 | 455 (55.56) | 464 (56.65) | 383 (46.76) | 72 (8.79) | 81 (9.89) | 283 (34.55) | 0.62 | 81.32 | 0.47 |

| LSIL | 576 | 530 (92.01) | 466 (80.90) | 454 (78.82) | 76 (13.19) | 12 (2.08) | 34 (5.90) | 0.36 | 84.72 | <0.001 |

| ASC-H | 128 | 104 (81.25) | 102 (79.69) | 95 (74.22) | 9 (7.03) | 7 (5.47) | 17 (13.28) | 0.60 | 87.50 | 0.62 |

| HSIL | 176 | 171 (97.16) | 166 (94.32) | 164 (93.18) | 7 (3.98) | 2 (1.14) | 3 (1.70) | 0.38 | 94.89 | 0.10 |

| AMP 1.5/hc2, HPV stratification | ||||||||||

| Group | N | hc2+ (%) | Amp+ (%) | hc2+/AMP+ (%) | hc2+/AMP− (%) | hc2-/AMP+ (%) | hc2-/AMP− (%) | Kappa | Agreement (%) | p |

| HPV16 | 577 | 501 (86.83) | 530 (91.85) | 483 (83.71) | 18 (3.12) | 47 (8.15) | 29 (5.03) | 0.41 | 88.73 | <0.001 |

| HPV18 | 160 | 124 (77.50) | 148 (92.50) | 119 (74.38) | 5 (3.13) | 29 (18.13) | 7 (4.38) | 0.20 | 78.75 | <0.001 |

| HR11 | 1056 | 842 (79.73) | 917 (86.84) | 790 (74.81) | 52 (4.92) | 127 (12.03) | 87 (8.24) | 0.40 | 83.05 | <0.001 |

| NonHR | 476 | 151 (31.72) | 58 (12.18) | 13 (2.73) | 138 (28.99) | 45 (9.45) | 280 (58.82) | −0.06 | 61.55 | <0.001 |

| Neg | 898 | 51 (5.68) | 112 (12.47) | 4 (0.45) | 47 (5.23) | 108 (12.03) | 739 (82.29) | −0.03 | 82.74 | <0.001 |

hc2: Hybrid Capture 2; AMP: Amplicor. HPV risk groups are determined by the presence of the respective type in LA or LBA. HR11: All targeted carcinogenic types without HPV16 and HPV18; NonHR: All HPV types except targeted carcinogenic types; Neg: negative for HPV by LA or LBA. Differences were tested for statistical significance using an exact McNemar’s χ2 test.

Analytical performance of Amplicor

In order to analyze the analytical performance of Amplicor, the Amplicor results at the 0.2 and 1.5 cutoffs were compared to the HPV genotyping results from all samples with single HPV genotype infections (n = 815). Single type infections were grouped in six HPV risk categories: HPV16, HPV18, other targeted carcinogenic types (HR11), HPV66 (as a non-targeted, but carcinogenic type that is frequently detected by hc2), HPV53/67/70/82 (as non-carcinogenic types that are frequently detected by hc2), and other HPV types. At both cutoffs, Amplicor showed significantly higher detection rates of targeted types than hc2 (Table 3). In contrast, Amplicor had significantly lower detection rates for non-targeted types that are frequently detected by hc2. Only the detection rate of other non-carcinogenic types (excluding HPV53, 67, 70, and 82) was slightly greater for Amplicor than for hc2 (significant only at the 0.2 cutoff), and specifically HPV61 was more frequently detected by Amplicor than hc2 (p = 0.008 at the 1.5 cutoff) (Supplementary Table 1). When raising the cutoff from 0.2 to 1.5 for Amplicor, a smaller fraction of positive results for targeted HPV genotypes at the 0.2 cutpoint were reclassified as negative at the 1.5 cutpoint (34 of 462; 7.4%) than was observed for the non-targeted HPV genotypes (45 of 352, 12.8%) (p = 0.01), which explains the increased clinical accuracy at the higher cutpoint compared to the lower cutpoint.

Table 3.

Detection of cases positive for single HPV genotypes (n=815) by Amplicor and Hybrid Capture 2 (hc2) stratified by HPV risk groups (defined by Linear Array (LA) and/or Line Blot Assay (LBA) test results) in women referred to ALTS for an atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASCUS) Pap. Cases were attributed to HPV risk groups hierarchically as follows: HPV16 > HPV18, other carcinogenic types (HR11) > HPV66 > HPV53/67/70/82 > other HPV.

| Type | hc2 | Amplicor at 0.2 cutpoint |

p | Amplicor at 1.5 cutpoint |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 75/102 (73.5%) | 99/107 (92.5%) | <0.001 | 93/107 (86.9%) | <0.001 |

| 18 | 22/35 (62.9%) | 32/35 (91.4%) | 0.001 | 32/35 (91.4%) | 0.001 |

| HR11 | 216/307 (70.4%) | 294/320 (91.9%) | <0.001 | 266/320 (83.1%) | <0.001 |

| 66 | 16/26 (61.5%) | 5/27 (18.5%) | 0.001 | 0/27 (0%) | <0.001 |

| 53/67/70/82 | 39/72 (54.2%) | 18/76 (23.7%) | 0.009 | 5/76 (6.6%) | <0.001 |

| Other | 26/237 (11.0%) | 60/249 (24.1%) | <0.001 | 33/249 (13.3%) | 0.04* |

Single HPV genotype infections were determined by LA or LBA positivity. hc2: Hybrid Capture 2; HR11: Targeted carcinogenic types without HPV16 and HPV18. Differences were tested for statistical significance using an exact McNemar’s χ2 test.

not significant after correction for multiple testing

CIN3+ cases not detected by Amplicor and hc2

We analyzed the HPV genotypes found in the CIN3+ cases missed by either Amplicor and/or hc2. Twelve and 21 cases of CIN3+ were negative by Amplicor at the 0.2 and 1.5 cutpoints, respectively, while 21 cases tested negative by hc2. Cases missed by Amplicor at either cutpoint primarily tested positive for non-targeted HPV genotypes whereas cases missed by hc2 primarily tested positive for targeted HPV types (Table 4). In addition, we analyzed the HPV genotypes at the time of CIN3+ diagnosis based on the LBA results (LA data was not available for later time points). Despite some genotype changes that suggest incident infections might have caused these cases, still hc2 missed more cases related to HPV16 while Amplicor was more likely to miss cases related to non-targeted types (Supplemental Table 2).

Table 4.

HPV genotypes (defined by Linear Array (LA) and/or Line Blot Assay (LBA) test results) found in 2-year cumulative cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 or more severe (CIN3+) cases as diagnosed by QC pathology missed by Amplicor and Hybrid Capture 2 (hc2) in women referred into ALTS for an atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance (ASCUS) Pap

| Type | Total missed |

Missed by Amplicor at 0.2 cutpoint |

Missed by Amplicor at 1.5 cutpoint |

Missed by hc2 |

Missed by Amplicor at 0.2 cutpoint and hc2 |

Missed by Amplicor at 1.5 cutpoint and hc2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 18 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| HR11 | 8 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 1 | 2 |

| 66 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 53/67/70/82 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Other | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| NA | 7 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 31 | 12 | 21 | 21 | 9 | 12 |

Cases were attributed to HPV risk groups in hierarchical order: HPV16> HPV18 > HR11 (targeted carcinogenic types without HPV16 and HPV18) > HPV66 (non-targeted carcinogenic type frequently detected by hc2) > HPV53, HPV67, HPV70, HPV82 (non-carcinogenic types frequently detected by hc2) > Other (other HPV genotypes). NA: sample was not tested for HPV genotypes.

Discussion

With HPV detection most likely becoming an integral component of primary cervical cancer screening soon, it is important to identify the best assays to be used in screening. For several years, hc2 has been the only FDA-approved HPV detection assay and it has been used in the majority of cervical cancer screening studies. Based on a wealth of studies using hc2 there is excellent knowledge about the strengths and weaknesses of this test. Cross-reactivity with a number of non-targeted types has been reported for hc2 (16), the sensitivity of the assay can be compromised in less than optimal settings (31), and there is no specimen adequacy control included in this assay. Despite these limitations, hc2 has been proven a very robust assay with good clinical performance. Still, with HPV testing at the doorstep to screening programs around the world, it is necessary to have more than one reliable HPV test, and performance data on new assays is urgently required.

Based on the design of the Amplicor HPV assay, it might be used for similar applications as hc2: the test targets the same 13 carcinogenic HPV types and gives a dichotomous result for the presence of any of these types. One theoretical advantage of Amplicor compared to hc2 is that it uses amplification of the β-globin gene as an internal specimen adequacy control. The analysis of the globin results in our study showed that almost all samples contained DNA adequate for amplifying β-globin, only 21 samples (0.6%) had a β-globin cutoff below 0.2. Only 9 samples were found to be invalid based on β-globin and HPV ODs, consequently, our results would not have changed if the adequacy control was disregarded completely. The very high percentage of adequate samples in our study might be related to the rigorous sampling within a clinical trial. In regular clinical practice with less rigorous collection procedures, a specimen adequacy control might be more important.

The ALTS trial offers a unique opportunity to analyze the performance of HPV detection assays because of the excellent disease ascertainment: 2-year follow-up to overcome limitations in sensitivity in colposcopy, colposcopic evaluation of women who returned for their exit visit, and rigorous review of histologic endpoints. Meanwhile, HPV genotyping data obtained with several HPV typing assays are available for ALTS samples for reference and to examine the analytic specificity of each pooled probe assay (27).

However, we acknowledge that the results from ALTS primarily relate to the triage of equivocal cytology and cannot be translated directly to primary screening applications. The HPV type distribution of HPV-positive cytologically normal specimens is different than that of ASCUS/LSIL cytology and than that of HSIL cytology (32). Also, with a median age of 25, the ALTS population was very young. A limitation of our study was the use of archival STM specimens, rather than PreservCyt, in the Amplicor assay, for which the Amplicor assay protocol had not been developed. Yet, its overall performance for detection of CIN3+ and its comparability to hc2 shows that this was of a minor concern.

We performed a thorough evaluation of analytical and clinical sensitivity of Amplicor at different cutoffs. Although the 0.2 cutoff has been widely used in previous clinical studies (18–23), there are no published data on a formal evaluation of Amplicor performance at different cutoff levels. We observed a very low dynamic range of Amplicor ODs, with most samples showing a very high or completely saturated result; only 8% of the samples had OD values between 0.2 and 1.5. This contrasts with the wide dynamic range found for hc2 results that has been shown to correlate with viral load in some studies (33;34).

In our analysis, we found that the Amplicor 1.5 cutoff was only slightly less sensitive but considerably more specific than the 0.2 cutoff. In agreement with that, Youden’s index was highest at the 1.5 cutoff. At the 1.5 cutoff, the clinical performance of Amplicor most closely resembled that of hc2, although its specificity (47.5% vs. 50.6%, p < 0.001) and PPV (14.4% vs. 15.1%, p = 0.007) was still slightly lower than hc2.

At the 0.2 cutoff, Amplicor had 11% higher positivity rates than hc2, which would result in a significantly higher referral of women with ASCUS cytology to colposcopy (64% vs. 53%, p<0.001). It remains to be determined whether HPV-based triage would be still cost-effective at these increased referral rates (35). While our data support using the 1.5 Amplicor cutoff, deciding which cutoff to use certainly depends on the application and the relative importance of sensitivity and specificity for that application. If used as a screening test with the goal to achieve maximum sensitivity and negative predictive value to increase the screening intervals, making HPV testing cost-effective (36), choosing a lower cutoff may be appropriate. However, using a low cutoff in primary screening must await an appropriate triage test to be viable to avoid unnecessary high colposcopy referral rates.

We thoroughly studied the cross-reactivity pattern of Amplicor by evaluating the Amplicor levels in cases with single genotype infections by combining two HPV genotyping results to maximize HPV genotype sensitivity. At the 0.2 cutoff, there was a general low level cross-reactivity across many types that led to a similar frequency of cross-reactivity among single non-targeted types in this study as observed for hc2. Remarkably, when the Amplicor cutoff was raised to 1.5, there was an increase in analytic specificity for targeted HPV genotypes, with greater decrease in detection of non-targeted types than targeted types. Most of the non-targeted types frequently detected by hc2 (53, 66, 67, 70, 82) were detected at much lower frequencies by Amplicor. Only HPV61 was more frequently detected by Amplicor at all cutoffs versus hc2.

The higher cross-reactivity of hc2 resulted in a higher detection of LSIL associated with non-carcinogenic types as compared to Amplicor. This is consistent with a recent study of almost 6,000 women enrolled in the HPV Vaccine Trial in Costa Rica (CVT) (37).

Although at the Amplicor 1.5 cutoff, the sensitivity to detect CIN3+ was identical to hc2 in all study arms there were apparent HPV genotype differences between the missed cases: hc2 more likely missed cases caused by carcinogenic types, including HPV16 and HPV18, while Amplicor was more likely to miss cases caused by non-targeted types (Table 4). We know from large cross-sectional surveys of HPV genotype prevalence in cervical cancers that most cases worldwide are caused by HPV16 and HPV18, fewer by other carcinogenic types, but only very few by non-carcinogenic types (38). This suggests that the non-targeted/non-carcinogenic types either do not progress to cancer at all, or that their progression takes such a long time that they are usually detected before invasive cancer occurs. In contrast, there is increasing evidence that women with cancers and CIN3 caused by HPV16 are younger than women with cancers and CIN3 caused by other types, suggesting that HPV16-associated progression is faster than that of lesions caused by other types (39). Therefore, despite the similar sensitivity between Amplicor and hc2, the qualitative difference between the two assays could be important- it might be more acceptable to miss disease caused by a low-risk type than if it were caused by HPV16 or HPV18. Currently, we cannot discriminate between CIN3 lesions with lower- versus higher risk of invasion, but it is becoming increasingly clear that there is considerable heterogeneity in this disease category (3). While the current histology-based endpoints cannot address the potential misclassification of precancers, new molecular markers might improve the risk assessment and offer new approaches of cervical cancer screening, e.g. using a sensitive HPV detection assay as a primary screen and a sensitive but highly disease specific marker to determine the progression risk of HPV-positive women (40).

In summary, despite the higher analytic sensitivity and specificity of Amplicor (Figure 1B), its clinical sensitivity was only marginally higher and its specificity was significantly lower than that of hc2 (Figure 1A). Some CIN3+ cases positive for non-targeted types were missed by Amplicor but detected by hc2 due to the higher level of cross-reactivity. However, we currently do not know the relevance of detecting these cases, since progression to cancer seems to be very rare for lesions caused by non-targeted types. While Amplicor detected more cases caused by targeted types due to its higher analytical sensitivity, the increased detection rate comes at the price of detecting many infections that do not seem to be clinically relevant, at least in the young ALTS population and within the 2-year follow-up time period.

Finally, the performance of Amplicor at the 1.5 cutoff which closely mimics the performance of hc2 needs to be pursued further. For example, a re-analysis of previous studies using higher cutoff values would be very simple and could yield results quickly. If our results are confirmed in different studies, using a higher cutoff value for Amplicor than currently recommended might be desirable.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The excellent technical assistance of Meera Sangaramoorthy, Kennita Riddick, and Esther Kim is gratefully acknowledged.

Financial Support and Conflict of Interest Statement: The research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH and the National Cancer Institute. Some of the equipment and supplies used in the ALTS trial were donated or provided at reduced cost by Digene (Gaithersburg, MD), Cytyc (Boxborough, MA), National Testing Laboratories (Fenton, MO), DenVu (Tucson, AZ), TriPath Imaging (Burlington, NC), and Roche Molecular Systems (Alameda, CA). Roche Molecular Systems provided reagents and research support to the lab of Patti E. Gravitt. Cosette M. Wheeler has received support through her institution from Roche Molecular Systems for HPV genotyping studies.

Reference List

- 1.Schiffman M, Castle PE, Jeronimo J, Rodriguez AC, Wacholder S. Human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. Lancet. 2007;370:890–907. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61416-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCredie MR, Sharples KJ, Paul C, et al. Natural history of cervical neoplasia and risk of invasive cancer in women with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:425–434. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schiffman M, Rodriguez AC. Heterogeneity in CIN3 diagnosis. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:404–406. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiffman M. Integration of human papillomavirus vaccination, cytology, and human papillomavirus testing. Cancer. 2007;111:145–153. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A randomized trial on the management of low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology interpretations. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1393–1400. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Results of a randomized trial on the management of cytology interpretations of atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:1383–1392. doi: 10.1067/mob.2003.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kinney WK, Manos MM, Hurley LB, Ransley JE. Where's the high-grade cervical neoplasia? The importance of minimally abnormal Papanicolaou diagnoses. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:973–976. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00080-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carozzi FM, Del MA, Confortini M, et al. Reproducibility of HPV DNA Testing by Hybrid Capture 2 in a Screening Setting. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:716–721. doi: 10.1309/84E5-WHJQ-HK83-BGQD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Castle PE, Wheeler CM, Solomon D, Schiffman M, Peyton CL. Interlaboratory reliability of Hybrid Capture 2. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;122:238–245. doi: 10.1309/BA43-HMCA-J26V-WQH3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arbyn M, Sasieni P, Meijer CJ, Clavel C, Koliopoulos G, Dillner J. Chapter 9: Clinical applications of HPV testing: a summary of meta-analyses. Vaccine. 2006;24 Suppl 3 doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.05.117. S3-78-S3/89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bulkmans NW, Berkhof J, Rozendaal L, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA testing for the detection of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 and cancer: 5-year follow-up of a randomised controlled implementation trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1764–1772. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61450-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuzick J, Clavel C, Petry KU, et al. Overview of the European and North American studies on HPV testing in primary cervical cancer screening. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1095–1101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mayrand MH, Duarte-Franco E, Rodrigues I, et al. Human papillomavirus DNA versus Papanicolaou screening tests for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1579–1588. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Naucler P, Ryd W, Tornberg S, et al. Human papillomavirus and Papanicolaou tests to screen for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1589–1597. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wright TC, Jr., Massad LS, Dunton CJ, Spitzer M, Wilkinson EJ, Solomon D. consensus guidelines for the management of women with abnormal cervical screening tests. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:201–222. doi: 10.1097/LGT.0b013e3181585870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castle PE, Solomon D, Wheeler CM, Gravitt PE, Wacholder S, Schiffman M. Human papillomavirus genotype specificity of hybrid capture 2. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:2595–2604. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00824-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cogliano V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El GF. Carcinogenicity of human papillomaviruses. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:204. doi: 10.1016/s1470-2045(05)70086-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carozzi F, Bisanzi S, Sani C, et al. Agreement between the AMPLICOR Human Papillomavirus Test and the Hybrid Capture 2 assay in detection of high-risk human papillomavirus and diagnosis of biopsy-confirmed high-grade cervical disease. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:364–369. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00706-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mo LZ, Monnier-Benoit S, Kantelip B, et al. Comparison of AMPLICOR and Hybrid Capture II assays for high risk HPV detection in normal and abnormal liquid-based cytology: use of INNO-LiPA Genotyping assay to screen the discordant results. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monsonego J, Bohbot JM, Pollini G, et al. Performance of the Roche AMPLICOR human papillomavirus (HPV) test in prediction of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) in women with abnormal PAP smear. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:160–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stevens MP, Garland SM, Rudland E, Tan J, Quinn MA, Tabrizi SN. Comparison of the Digene Hybrid Capture 2 assay and Roche AMPLICOR and LINEAR ARRAY human papillomavirus (HPV) tests in detecting high-risk HPV genotypes in specimens from women with previous abnormal Pap smear results. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:2130–2137. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02438-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Ham MA, Bakkers JM, Harbers GK, Quint WG, Massuger LF, Melchers WJ. comparison of two commercial assays for detection of human papillomavirus (HPV) in cervical scrape specimens: validation of the Roche AMPLICOR HPV test as a means to screen for HPV genotypes associated with a higher risk of cervical disorders. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2662–2667. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2662-2667.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wahlstrom C, Iftner T, Dillner J, Dillner L. Population-based study of screening test performance indices of three human papillomavirus DNA tests. J Med Virol. 2007;79:1169–1175. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gravitt PE, Peyton CL, Alessi TQ, et al. Improved amplification of genital human papillomaviruses. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:357–361. doi: 10.1128/jcm.38.1.357-361.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peyton CL, Gravitt PE, Hunt WC, et al. Determinants of genital human papillomavirus detection in a US population. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1554–1564. doi: 10.1086/320696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiffman M, Wheeler CM, Dasgupta A, Solomon D, Castle PE. A comparison of a prototype PCR assay and hybrid capture 2 for detection of carcinogenic human papillomavirus DNA in women with equivocal or mildly abnormal papanicolaou smears. Am J Clin Pathol. 2005;124:722–732. doi: 10.1309/E067-X0L1-U3CY-37NW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castle PE, Gravitt PE, Solomon D, Wheeler CM, Schiffman M. Comparison of linear array and line blot assay for detection of human papillomavirus and diagnosis of cervical precancer and cancer in the atypical squamous cell of undetermined significance and low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion triage study. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:109–117. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01667-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ASCUS-LSIL Triage Study. Schiffman M, Adrianza ME. Design, methods and characteristics of trial participants. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:726–742. doi: 10.1159/000328554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solomon D, Schiffman M, Tarone R. Comparison of three management strategies for patients with atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance: baseline results from a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:293–299. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.4.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leisenring W, Pepe MS. Regression modelling of diagnostic likelihood ratios for the evaluation of medical diagnostic tests. Biometrics. 1998;54:444–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Arbyn M, Sankaranarayanan R, Muwonge R, et al. Pooled analysis of the accuracy of five cervical cancer screening tests assessed in eleven studies in Africa and India. Int J Cancer. 2008;123:153–160. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kovacic MB, Castle PE, Herrero R, et al. Relationships of human papillomavirus type, qualitative viral load, and age with cytologic abnormality. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10112–10119. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gravitt PE, Burk RD, Lorincz A, et al. A comparison between real-time polymerase chain reaction and hybrid capture 2 for human papillomavirus DNA quantitation. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12:477–484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pretet JL, Dalstein V, Monnier-Benoit S, Delpeut S, Mougin C. High risk HPV load estimated by Hybrid Capture II correlates with HPV16 load measured by real-time PCR in cervical smears of HPV16-infected women. J Clin Virol. 2004;31:140–147. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kulasingam SL, Kim JJ, Lawrence WF, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis based on the atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance/low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion Triage Study (ALTS) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:92–100. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goldhaber-Fiebert JD, Stout NK, Salomon JA, Kuntz KM, Goldie SJ. Cost-effectiveness of cervical cancer screening with human papillomavirus DNA testing and HPV-16,18 vaccination. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:308–320. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Safaeian M, Herrero R, Hildesheim A, et al. Comparison of the SPF10-LiPA system to the Hybrid Capture 2 Assay for detection of carcinogenic human papillomavirus genotypes among 5,683 young women in Guanacaste, Costa Rica. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1447–1454. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02580-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith JS, Lindsay L, Hoots B, et al. Human papillomavirus type distribution in invasive cervical cancer and high-grade cervical lesions: a meta-analysis update. Int J Cancer. 2007;121:621–632. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vinokurova S, Wentzensen N, Kraus I, et al. Type-dependent integration frequency of human papillomavirus genomes in cervical lesions. Cancer Res. 2008;68:307–313. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gravitt PE, Coutlee F, Iftner T, Sellors JW, Quint WG, Wheeler CM. New technologies in cervical cancer screening. Vaccine. 2008;26 Suppl 10:K42–K52. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.