Abstract

Background

Data from Arab world studies suggest that Arab women may experience a more aggressive breast cancer phenotype. To investigate this finding, we focused on one of the largest settlements of Arabs and Iraqi Christians (Chaldeans) in the US, metropolitan Detroit- a SEER reporting site since 1973.

Materials and Methods

We identified a cohort of primary breast cancer cases diagnosed 1973–2003. Using a validated name algorithm, women were identified as being of Arab/Chaldean descent if they had an Arab last or maiden name. We compared characteristics at diagnosis (age, grade, histology, SEER stage, and marker status) and overall survival between Arab-, European-, and African-Americans.

Results

The cohort included 1,652 (2%) women of Arab descent, 13,855 (18%) African-American women, and 63,615 (80%) European-American. There were statistically significant differences between the racial groups for all characteristics at diagnosis. Survival analyses overall and for each SEER stage showed that Arab-American women had the best survival, followed by European-American women. African-American women had the poorest overall survival and were 1.37 (95% confidence interval: 1.23–1.52) times more likely to be diagnosed with an aggressive tumor (adjusting for age, grade, marker status, and year of diagnosis).

Conclusion

Overall, Arab-American women have a distribution of breast cancer histology similar to European-American women. In contrast, the stage, age, and hormone receptor status at diagnosis among Arab-Americans was more similar to African-American women. However, Arab-American women have a better overall survival than even European-American women.

Keywords: Arab, breast cancer, epidemiology, incidence, survival

Background

Several papers from major treating hospitals in Arab countries have reported an early age of onset and a preponderance of aggressive breast cancer phenotype in their patients. [1–12] For example, papers from Tunisia report observations of rapidly progressing breast cancer in young women, suggestive of an inflammatory breast cancer histology. [5–8] In addition, others have reported that the majority (>50%) of breast cancer cases are diagnosed among women less than 50 [1,3,9] years of age; this is in comparison to US statistics which show that 22% of breast cancer cases are diagnosed in women under 50.

While these statistics give some relative comparisons, they are difficult to interpret given the variation in the population age structure between Arab countries and the US and the lack of detailed comparative studies between the US and Arab populations. In addition, it cannot be assumed that all breast cancer cases are systematically captured in most Arab countries, given the extreme paucity of systematic population screening for early detection in those regions. The well-established tumor registry in Israel gives data for the Jewish and Arab populations separately. Age-adjusted and standardized incidence rates from this registry show that the Arab Israeli population has a lower overall incidence of breast cancer compared to the US (36.7 per 100,000 compared to 97.2 per 100,000) and a later age at onset. Recently the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC), in conjunction with the US National Cancer Institute (NCI), published cancer statistics from four Middle East countries: Israel, Cyprus, Jordan, and Egypt (Tanta). [13] The Tanta registry in Egypt, which is also population based, reports age-adjusted and standardized incidence rates of breast cancer higher than those of the Israeli Arab population for women <60 years as well as a higher overall incidence rate of 50 per 100,000. It is possible that given the diversity of the populations of the Arab world, the breast cancer experience varies among groups. Such variation, if it does exist, could be due to differences in genetic background, environmental exposures, or reproductive behaviors.

Metropolitan Detroit is home to the largest Arabic-speaking population outside of the Middle East. The city of Dearborn, the near west suburb of Detroit, has been a center of Arab culture and immigration since the late 1800’s. Immigrant populations include Yemenis, Syrians, Palestinians, Egyptians, and Iraqis, including Chaldeans (Christian Iraqis). Political unrest in other Arab countries has also contributed to the heterogeneity of the Detroit Arab population. According to the 2000 Census, which included the option to report country of origin, the metropolitan Detroit Arab population is 44% Lebanese, 32% Chaldean, 10% Iraqi, 6% Syrian, 3% Palestinian, 2% Egyptian, and 2% Jordanian. [14]. These Census data were collected before 9/11/2001, when fear of discrimination among American Arab and Muslim populations increased dramatically; therefore, the reported proportions are thought to be representative, despite the usual expected undercount from self-reported statistics.

Detroit has been part of the NCI’s national tumor registry, the Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program, since the registry’s inception in 1973. The large Arab-American community in Detroit gave us the opportunity to characterize in a population-based framework, the patterns of breast cancer experienced by Arab women versus other ethnic groups. Out work was highly facilitated by the advent of a validated name algorithm, which allowed the identification of women of Arab decent in the registry so that a comparison could be made to white, non-Hispanic (European) and African-America women. [15] Our a priori hypothesis, based on the papers from the Arab world, was that Arab-American women would have poorer prognostic characteristics at the time of diagnosis than European-American women and worse survival.

Methods

In contrast to the behavior of many other migrating populations, Arabs have maintained their cultural names after immigrating and settling in the US. Using a previously published and validated algorithm to identify Arab ethnicity by name [13], we identified women with an Arab first, last, or maiden name in the Detroit SEER registry. We used data from the start of the registry in 1973, up to and including 2003. We compared women identified as being Arab to non-Hispanic, non-Arab Caucasian women (henceforth termed European-American) and to African-American women. The small percentage of women with other racial identities where excluded from this analysis.

We compared Arab women to European- and African-American women on several prognostic indicators at diagnosis including age, histology, grade, estrogen (ER) and progesterone (PR) marker status, and SEER stage. For each indicator, we first tested for global association with race using a chi-square test. For indicators with a significant chi-square, we calculated the odds ratio for that factor by race to characterize the variation.

We evaluated overall survival using Kaplan-Meier and Cox Proportional Hazard models for each racial group. Adjusted hazard ratios were calculated for each race adjusting for age, grade, ER/PR marker status, SEER stage, histology and year of diagnosis. We tested for interactions between race as well as age and each of the prognostic characteristics; significant interactions were retained in the model along with their main effects.

Results

Study Cohort

There were 80,316 women diagnosed with primary breast cancer in the Detroit SEER registry between 1973 and 2003. We excluded 9 females diagnosed < 18 years of age, 1,095 women with a race/ethnicity other than Arab-, European- or African-American, and 91 cases were excluded due to uncommon non mammary epithelial histology (e.g., melanoma of the breast). The resulting analytic sample (n=79,121) was 80% European-American, 18% African-American, and 2% Arab-American. (Table 1) The overall mean age at diagnosis was 60 years. In situ cases represent 12% of the cohort and 46%, 30%, and 6% had local, regional, or distant disease, respectively, with 6% of an unknown stage.

Table 1.

Study population characteristics.

| Race | n | (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Eur1 | 63614 | (80%) |

| Afr | 13855 | (18%) |

| Arb | 1652 | (2%) |

| SEER Stage | ||

| In Situ | 9643 | (12%) |

| Local | 36622 | (46%) |

| Regional | 23754 | (30%) |

| Distant | 4652 | (6%) |

| Unknown | 4450 | (6%) |

| Mean age at diagnosis | 60 (SD 14) | |

| Eur | 61 | |

| Afr | 58 | |

| Arb | 57 | χ2 p-value < 0.001 |

Eur= European-American; Afr= African-American; Arb= Arab-American

Characteristics at Diagnosis

Age

The mean ages at diagnosis were 61, 57, and 58 years, for European-American, Arab-, and African-American women, respectively (Table 1). We calculated a log-rank test to compare the distribution of age at diagnosis among the three ethnic groups, which was statistically significant (p<0.001). Each pairwise log-rank test was also significant (p<0.001).

Stage

The distribution (number and percent) of SEER staging categories is presented in Table 2a. There was a statistically significant overall chi-square for the distributions of stage at diagnosis by race (p<0.0001). Table 2b gives the unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for each SEER stage at diagnosis comparing African-American and Arab-American cohorts individually to European-American women. Arab-American women were significantly less likely to be diagnosed with local disease (OR=0.82; 95% CI 0.74–0.91) and significantly more likely to be diagnosed with regional disease (OR 1.18; 95% CI 1.06–1.30). Similarly, African-American women were less likely to be diagnosed with local disease (OR=0.74; 95% CI 0.71–0.77) and more likely to be diagnosed with regional (OR=1.20; 95% CI 1.15–1.25) and distant disease (OR=1.60; 95% CI 1.50–1.72).

Table 2.

| Table 2a. Distribution of SEER Stage at Diagnosis for European-, African-, and Arab-American women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Eur | Afr | Arb |

| In Situ | 77341 (12%) | 1700 (12%) | 209 (13%) |

| Local | 30335 (48%) | 5579 (40%) | 708 (43%) |

| Regional | 18614 (29%) | 4599 (33%) | 541 (33%) |

| Distant | 3408 (5%) | 1152 (8%) | 92 (6%) |

| Unknown | 3523 (6%) | 825 (6%) | 102 (6%) |

| Table 2b. Odds Ratios (with 95% Confidence Intervals) for SEER Stage at diagnosis comparing African-American and Arab-American women individually to European-American women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Stage | Eur | Afr | Arb |

| In Situ | 1.0 | 1.01 (0.95–1.07) | 1.05 (0.90–1.21) |

| Local | 1.0 | 0.74 (0.71–0.77) | 0.82 (0.74–0.91) |

| Regional | 1.0 | 1.20 (1.15–1.25) | 1.18 (1.06–1.30) |

| Distant | 1.0 | 1.60 (1.50–1.72) | 1.04 (0.84–1.29) |

| Unknown | 1.0 | 1.08 (0.99–1.17) | 1.12 (0.92–1.38) |

Overall χ2 p-value<0.0001

Histology

Table 3a shows the number and proportion of each histological type by race. The overall chi-square was significant at p<0.0001. The histological tumor type was not significantly different for Arab-American women compared to European-American women. However, notable odds ratios included invasive (OR=0.86; 95% CI 0.73–1.02) which is borderline significant and metaplastic (OR=2.57; 95% CI 0.61–10.76). (Table 3b) African-American women differed significantly from European-American women for invasive (OR=0.63; 95% CI 0.59–0.67), papillary (OR=1.86; 95% CI 1.62–2.12), comedo (OR=1.26; 95% CI 1.14–1.38), medullary (OR=2.03; 95% CI 1.82–2.27), Paget’s (OR=1.58; 1.16–2.15), and inflammatory (OR=1.53; 95% CI 1.30–1.81) categories.

Table 3.

| Table 3a. Distribution of Tumor Histology at Diagnosis for European-, African-, and Arab-American women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | Eur | Afr | Arb |

| Invasive* | 58,469 (92%) | 12,166 (88%) | 1,499 (91%) |

| Metaplastic | 30 (0.05%) | 12 (0.09%) | 2 (0.12%) |

| Papillary | 762 (1.2%) | 305 (2.2%) | 21 (1.3%) |

| Squamous | 58 (0.09%) | 21 (0.15%) | 2 (0.12%) |

| Comedo | 1,977 (3%) | 536 (4%) | 62 (4%) |

| Medullary | 1,027 (2%) | 447 (3%) | 27 (2%) |

| Sarcomas | 160 (0.2%) | 55 (0.4%) | 5 (0.3%) |

| Pagets | 562 (1%) | 124 (1%) | 17 (1%) |

| Inflammatory | 569 (0.9%) | 189 (1.4%) | 17 (1.0%) |

| Table 3b. Odds Ratios (with 95% Confidence Intervals) for histology at diagnosis comparing African-American and Arab-American women individually to European-American women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Histology | Eur | Afr | Arb |

| Invasive* | 1.0 | 0.63 (0.59–0.67) | 0.86 (0.73–1.02) |

| Metaplastic | 1.0 | 1.84 (0.94–3.59) | 2.57 (0.61–10.76) |

| Papillary | 1.0 | 1.86 (1.62–2.12) | 1.06 (0.69–1.64) |

| Squamous | 1.0 | 1.66 (1.01–2.74) | 1.34 (0.32–5.44) |

| Comedo | 1.0 | 1.26 (1.14–1.38) | 1.22 (0.94–1.57) |

| Medullary | 1.0 | 2.03 (1.82–2.27) | 1.01 (0.69–1.49) |

| Sarcomas | 1.0 | 1.01 (0.83–1.23) | 1.17 (0.72–1.89) |

| Pagets | 1.0 | 1.58 (1.16–2.15) | 1.20 (0.49–2.94) |

| Inflammatory | 1.0 | 1.53 (1.30–1.81) | 1.15 (0.71–1.87) |

Overall χ2 p-value<0.0001

Invasive, not otherwise specified

Marker Status

Estrogen-receptor (ER) and progesterone-receptor (PR) status at diagnosis are important prognostic factors and robust predictors of response to hormonal therapy. The distribution of ER/PR combined status is given in Table 4a. Overall chi-square for differences in the distribution of ER/PR between the three racial groups was p<0.0001. Arab-American women were more likely, though of borderline significance, to have ER− disease compared to European-American women (OR=1.17; 95% CI 0.97–1.40); and significantly more likely to have ER−/PR− tumors (OR=1.29; 95% CI 1.08–1.54). (Table 4b) African-American women were significantly more likely at diagnosis to have tumors that where ER− (OR=2.29; 95% CI 2.15–2.46), PR− (OR=1.84; 95% CI 1.73–1.96) or ER and PR negativity combined ((ER−/PR−) OR=2.09; 95% CI 1.97–2.12) when compared to European-American women. The graph in conjunction with Table 4b depicts the proportion of each ER/PR pair status by race and age at diagnosis dichotomized by age <50 and ≥50. Of note, the proportion of ER+/PR+ tumors in African-American women ≥50 is lower than the proportion seen in Arab- or European-American women <50.

Table 4.

| Table 4a. Distribution of Marker Status at Diagnosis for European-, African-, and Arab-American women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Eur | Afr | Arb |

| ER+/PR+ | 12,926 (64%) | 2,322 (47%) | 382 (63%) |

| ER+/PR− | 2,750 (13%) | 607 (13%) | 73 (12%) |

| ER−/PR+ | 577 (3%) | 189 (4%) | 24 (4%) |

| ER−/PR− | 4,017 (20%) | 1,710 (36%) | 132 (21%) |

| Table 4b. Odds Ratios (with 95% Confidence Intervals) for marker status at diagnosis comparing African-American and Arab-American women individually to European-American women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Marker | Eur | Afr | Arb |

| ER− | 1.0 | 2.29 (2.15–2.46) | 1.17 (0.97–1.40) |

| PR− | 1.0 | 1.84 (1.73–1.96) | 1.01 (0.85–1.19) |

| ER−/PR− | 1.0 | 2.09 (1.97–2.12) | 1.29 (1.08–1.54) |

Overall χ2 p-value<0.0001

(Note: Frequency missing is 53412 due to data capture not beginning until 1990.)

Grade

The distribution of the grade at diagnosis for European-, African-, and Arab-American women is given in Table 5a. The overall chi-square for a difference in the distribution between groups was p<0.0001. Arab-American women were less likely to have well-differentiated (OR=0.86; 95% CI 0.71–1.05) and unknown (OR=0.86; 95% CI 0.78–0.95) tumors at diagnosis than European-American women. (Table 5b) They were significantly more likely to have poorly differentiated tumors (OR=1.25; 95% CI 1.11–1.41). African-American women were significantly less likely to have either well-differentiated (OR=0.71; 95% CI 0.66–0.77) or moderately differentiated (OR=0.90; 95% CI 0.86–0.95) tumors as well as tumors with unknown differentiation (OR=0.78; 95% CI 0.75–0.81). In addition, they were significantly more likely to have poorly differentiated (OR=1.72; 95% CI 1.65–1.79) or undifferentiated (OR=1.79; 95% CI 1.52–2.11) tumors.

Table 5.

| Table 5a. Distribution of Grade at Diagnosis for European-, African-, and Arab-American women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Eur | Afr | Arb |

| Well | 4,915 (8%) | 780 (6%) | 111 (7%) |

| Moderately | 11,302 (18%) | 2,257 (16%) | 317 (19%) |

| Poorly | 11,023 (17%) | 3,668 (26%) | 343 (21%) |

| Undifferentiated | 511 (0.8%) | 198 (1.4%) | 13 (0.8%) |

| Unknown | 35,863 (56%) | 6,952 (50%) | 868 (53%) |

| Table 5b. Odds Ratios (with 95% Confidence Intervals) for grade at diagnosis comparing African-American and Arab-American women individually to European-American women | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade | Eur | Afr | Arb |

| Well | 1.0 | 0.71 (0.66–0.77) | 0.86 (0.71–1.05) |

| Moderately | 1.0 | 0.90 (0.86–0.95) | 1.10 (0.97–1.24) |

| Poorly | 1.0 | 1.72 (1.65–1.79) | 1.25 (1.11–1.41) |

| Undifferentiated | 1.0 | 1.79 (1.52–2.11) | 0.98 (0.56–1.70) |

| Unknown | 1.0 | 0.78 (0.75–0.81) | 0.86 (0.78–0.95) |

Overall χ2 p-value<0.0001

Small tumors with positive nodes

We hypothesize that a surrogate for biologically aggressive disease is a tumor that even though is small at the primary site (< 1 cm) has evidence of nodal metastases. Table 6 gives the results of our analysis of small tumors with positive nodes at diagnosis. Both Arab- and African-American women were more likely to be diagnosed with this type of tumor than European-American women; however, the results for Arab-Americans were of borderline significance for both the unadjusted or adjusted analysis. Interestingly, the odds ratios for both Arab- and African-American women increased in magnitude after adjustment.

Table 6.

Unadjusted and adjusted Odds Ratio for probability of being diagnosed with a small tumor (<1cm) with positive nodes

| OR | 95% CI | aOR* | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eur | 1.0 | --- | 1.0 | --- |

| Afr | 1.15 | (1.06–1.24) | 1.37 | (1.23–1.52) |

| Arb | 1.18 | (0.96–1.45) | 1.27 | (0.98–1.67) |

Adjusting for age, histology, grade, marker status, year of diagnosis

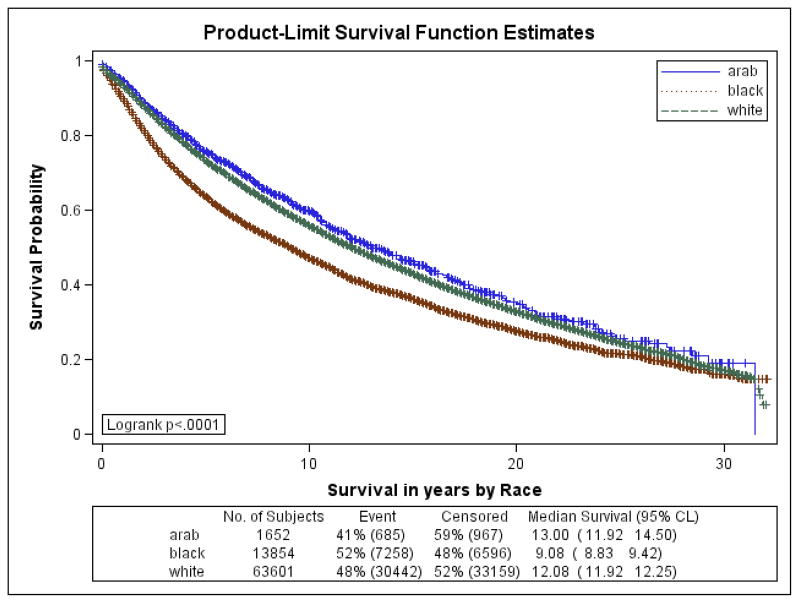

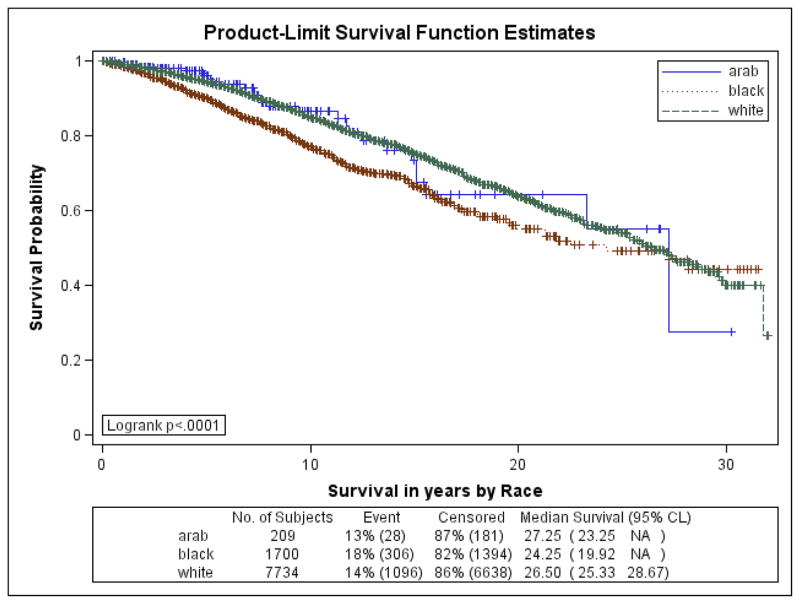

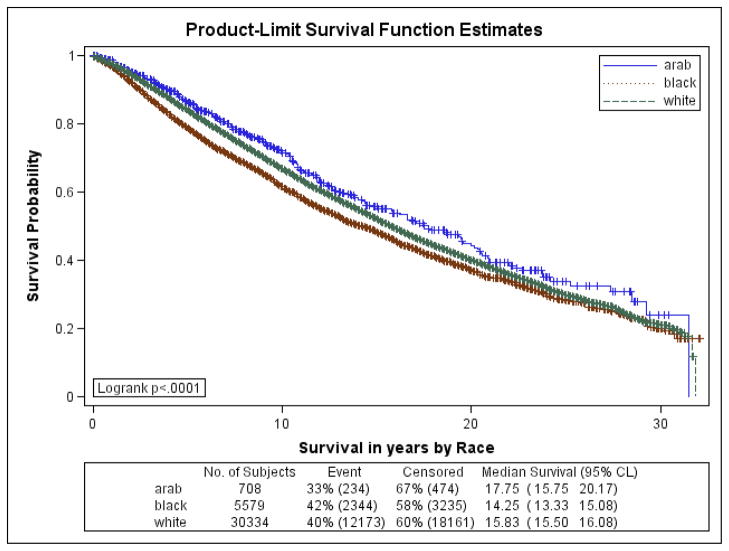

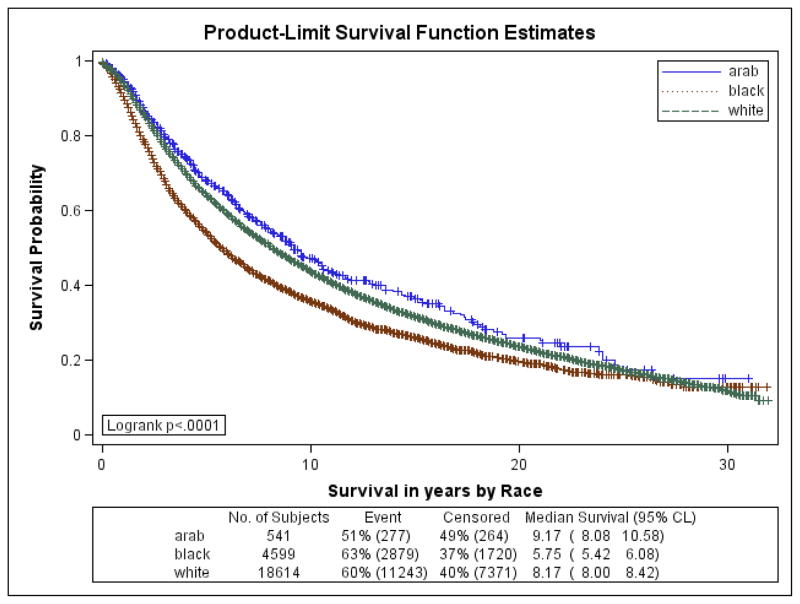

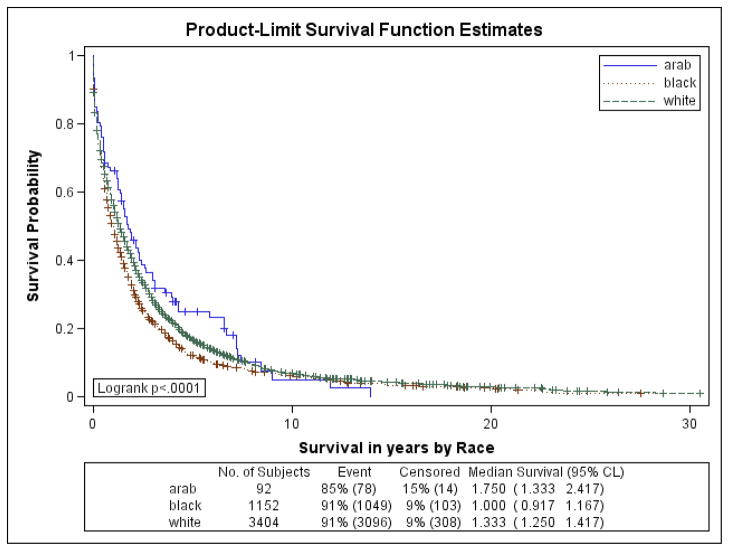

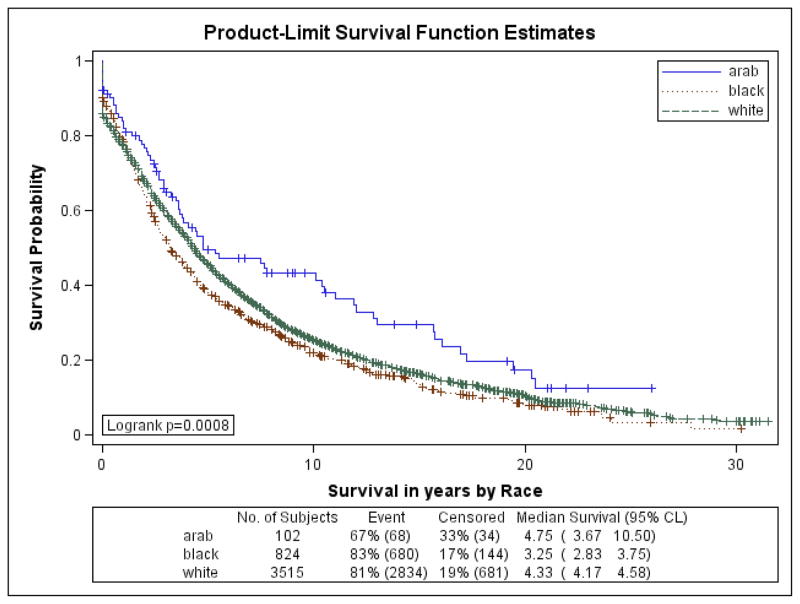

Survival Overall and Adjusted

Figures 1a–1f are the Kaplan Meier plots for overall survival and for survival by SEER stage at diagnosis. In all graphs, Arab-American women have the best survival followed, usually closely, by European-Americans. African-American women have considerably worse survival. In Table 7, the unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) from the Cox Proportional Hazards models are presented. Hazard ratios include an interaction term for race-by-age and age-by-marker status, and were adjusted for histology, age at diagnosis, marker status, year of diagnosis, grade, and stage. Commensurate to the graphs, Arab-American women have significantly better survival (HR=0.83; 95% CI 0.74–0.92) in the unadjusted analysis. The magnitude of the estimate is similar in the adjusted analysis but does not reach significance. Notably, African-American women have a significantly higher mortality than European-American women in the unadjusted (HR=1.21; 95% CI 1.17–1.25) and more profoundly in the adjusted (HR=1.93; 95% CI 1.46–2.55) analyses.

Figure 1.

Figure 1a. Kaplan-Meier Curves by Race for Overall Survival

Figure 1b. Kaplan-Meier Curves by Race for 5-year Overall Survival for Insitu SEER Stage at Diagnosis

Figure 1c. Kaplan-Meier Curves by Race for 5-year Overall Survival for Local SEER Stage at Diagnosis

Figure 1d. Kaplan-Meier Curves by Race for 5-year Overall Survival for Regional SEER Stage at Diagnosis

Figure 1e. Kaplan-Meier Curves by Race for 5-year Overall Survival for Distant SEER Stage at Diagnosis

Figure 1f. Kaplan-Meier Curves by Race for 5-year Overall Survival for Unknown SEER Stage at Diagnosis

Table 7.

Cox Proportional Hazards Ratios for 5 year survival

| HR | 95% CI | aHR* | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eur | 1.0 | --- | 1.0 | --- |

| Afr | 1.21 | (1.17–1.25) | 2.3 | (1.75–3.03) |

| Arb | 0.83 | (0.74–0.92) | 0.74 | (0.30–1.82) |

Adjusting for histology, age at diagnosis, marker status, year of diagnosis, grade, stage, and interaction between race and age.

Discussion

Data from the Arab world varies regarding the reported breast cancer experience of women. A retrospective review of 292 patients seen at King Fahd Hospital from 1985–1995 showed that 78% of patients were younger than 50 at diagnosis and 79% were pre-menopausal. [3] Similarly, in Lebanon, 49% of breast cancer cases diagnosed between 1983–1995 (n=2673) were <50 years of age. [9] There is only one oncology clinic in Libya which maintains a tumor registry for all cases receiving consultation. Between 1981–1985, breast cancer was the most frequently diagnosed cancer in women, 72% of whom were less than 50 years of age. [1] The data from these studies represent hospital based observations and are thus hard to interpret, without additional information. For example, it is possible that only younger women seek treatment for their breast cancer resulting in a selection bias in the data reported.

In two Egyptian studies, alternative study designs were applied with similar results. Abdel-Rahman et al [11] used a case-control design to assess epidemiologic features of breast cancer. Results of this study were notable for age at diagnosis and several risk factors. Forty-four percent of cases were diagnosed less than or equal to 50 years of age. Cases were more likely than controls to have a family history of breast cancer, to have a history of radiation exposure, to be working, as well as several reproductive factors including higher age at first birth, lower parity, and artificial menopause. Although this study offers some potential explanations for the age distribution of cases, the cases still may have been differentially selected.

Soliman et al [12] conducted a review of mortality data in Egypt where death certificates are required to receive a burial permit. Records reviewed for the period of January 1, 1992 to December 31, 1996 were compared to US mortality statistics (1991–1995). Results from this population based study showed a higher age-specific mortality for breast cancer among women less than 40.

Recently, the US NIH/National Cancer Institute partnered with the Middle East Cancer Consortium (MECC) to publish cancer incidence data from four MECC countries (Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, and Jordan) [13]. Israel, which has a diverse population, reported age-standardized breast cancer incidence rates of 93 per 100,000 for Israeli Jews and 36.7 for Israeli Arabs. Rates per 1000,000 reported for Cyprus, Egypt, and Jordan were 57.7, 49.6, and 38.0, respectively. For comparison, the US SEER rate for all US women over a similar time period was 97.2. Rates for Oman and Kuwait were also available in Volume VIII of the International Agency for Research on Cancer’s Cancer Incidence in Five Continents [16]. For 1993–1997, the age-standardized breast cancer rate per 100,000 was 12.7 in Oman. Kuwait’s reported age-adjusted breast cancer rate for Kuwaitis between 1994–1997 was 32.8 per 100,000. Data quality issues for both countries were noted in the publication.

Using data from the metropolitan Detroit SEER, where an estimated 500,000 Arab-Americans reside, we present the first report of breast cancer characteristics at diagnosis among Arab-American women. Our results suggest that Arab-American have a different breast cancer experience from both Caucasian- and African-Americans. They were diagnosed at a younger age and had more regional disease and poorly differentiated ER−/PR− disease than their European-American counterparts. Although not statistically significant, there was also a trend observed in our data for Arab-American women to be more likely to have small tumors with positive nodes. Importantly, these differences in disease characteristics which would suggest poorer prognosis, did not translate into a survival disadvantage. This may reflect the diversity of disease experienced in a genetically heterogeneous group of Arabs in the Detroit area, or represent biologically aggressive disease that is responsive to treatment that is widely accessible and thus results in equivalent survival to less aggressive disease more characteristic of Caucasian Americans. With regards to genetic heterogeneity, the term “Arab” refers to an individual from any one of 23 different countries that span geographic and cultural expanses from Mauritania to Oman and from Somalia to Syria and Morocco. The rich cultural diversity of the region includes differences in marriage practices, including currently practiced consanguineous marriages, differences in social behaviors, and a wide-range of environmental exposures including oil production and agricultural practices. An interesting hypothesis that we could not investigate in this analysis is whether the length of residence within the US influences the breast cancer experience of Arab-American women. Other immigration studies have shown that recent migrants maintain the breast cancer risk profile of their native country, but subsequent generations assume the risk profile for the adopted country. SEER does not capture country of birth or date of immigration, which is a limitation in our analysis.

The Arab-American experience for any of the characteristics examined was never as poor as that observed among African-American women. Our study is very robust in distinguishing the relative proportions between all combinations of estrogen and progesterone receptor status, an area of active current interest and investigation. Our results clearly reaffirm that African-Americans are much less likely than either Caucasians or Arab-Americans to present with ER+/PR+ disease and much more likely to present with ER−/ER− disease, whereas the mixed phenotypes of hormonal receptor expression status are relatively similar amongst all the populations. This is a striking finding, especially considering that preponderance of ER−/PR− disease is true in African-Americans for all ages. Several recent review papers have evaluated the potential contributions to breast cancer differences in African-Americans and Caucasians. [17–20] Although it is likely that screening and treatment differences contribute to the disparity in outcomes, it is also clear that differences in tumor biology are important. Polite and Olopade [18] note in their review the evidence of significant tumor biology differences in hormone receptor and HER2 status, grade, S-phase fraction, BRCA-1/2 mutations of unknown significance, and P53. Even when controlling for known differences in tumor biology as well as screening, treatment, and socio-demographic factors, the mortality difference between African-Americans and Caucasians cannot be completely explained. It is likely that as yet unidentified biological differences exist.

We found that delineating the racial distribution of the histologies from the SEER registry was a difficult task, particularly since the analysis includes data from 1973 to 2003, a period during which a major revision of the SEER abstracting guidelines (1988) and changes in the clinical interpretation of the pathology took place. Due to the Tunisian reports, we were interested to examine differences in the proportion of inflammatory breast cancer among the three ethnicities. However, since there is not an ICD-O designation for inflammatory breast cancer (IBC), we used information from the extent of disease codes. Our classification of IBC using this approach is most likely somewhat imprecise. However, assuming non-differential misclassification between ethnic groups, however, we would surmise that the relative differences are accurate, despite the imprecision of the absolute frequency. One other study has used SEER data to evaluate racial differences in inflammatory breast cancer incidence and our results generally agree with the previous findings. We found that African-American women were significantly more likely to be diagnosed with inflammatory breast cancer (OR=1.53; 95% CI 1.30–1.81) than European-American women. Our results are consistent with those of Hance et al, who also reported a higher frequency of inflammatory breast cancer in African-Americans. [21] However, ours is the first report of the proportion of IBC amongst Arab Americans, a subject of great interest, given the increased proportion of IBC in North Africa.

Finally, it is worth noting that if denominator data were available for the Arab community, we would have calculated standardized age-adjusted incidence rates. We suspect that the underlying age distribution structure of the Arab community is younger than that of either the European- or African-American communities in Detroit. Because Arab ethnicity has been grouped with “Caucasian” in US government population based data collection efforts, we cannot identify the age structure or total population of Arab-Americans in Detroit or elsewhere in the US. Even if we use self-reported country of origin or language spoken at home, the population estimates are most likely an undercount. Our research within this important minority community is significantly hampered by the lack of accurate population estimates and age structure data. The current socio-political climate suggests that further Arab immigration to the US is expected. Detroit alone is anticipating thousands of Iraqi immigrants in the next 12 months from the United Nation’s efforts to resettle Iraqi refugees. [22–23] Recognition of Arabs as a separate minority group and detailed analyses of their breast cancer burden would allow better population statistics for public health research, policy, and social support services.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Department of Defense Breast Cancer Resaerch Program Predoctoral Fellowship (W81XWH-04-1-0395 to SHA), by grants from the Breast Cancer Foundation (SDM) and the Burroughs Wellcome Fund (SDM), and the National Institutes of Health through the University of Michigan’s Cancer Center Support (5 P30 CA46592 to SBG and SDM). The funding sources were not involved in the study design or data collection, analyses, or interpretation. The authors had full responsibility of the writing of the manuscript and the decision to submit for publication. The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.Akhtar SS, Abu Bakr MA, Dawi SA, Ikram-ul-Huq Cancer in Libya- A retrospective study (1981–1985) Afr J Med Med Sci. 1993;22:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Idrissi HY, Ibrahim EM, Kurashi NY, Sowayan SA. Breast cancer in a low-risk population. The influence of age and menstrual status on disease pattern and in survival in Saudi Arabia. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:48–51. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ibrahim EM, Al-Mulhim FA, Al-Amri A, Al-Muhanna FA, Ezzat AA, Stuart RK, Ajarim D. Breast Cancer in the eastern province of Saudi Arabia. Med Onco. 1998;15:241–247. doi: 10.1007/BF02787207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiedozi LC, El_hag IA, Kollur SM. Breast diseases in the norther region of Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2003;6:623–627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tabbane F, Muenz L, Jazira M, Cammoun M, Belhassen S, Mourali N. Clinical and prognostic features of a rapidly progressing breast cancer in Tunisia. Cancer. 1977;40:376–382. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197707)40:1<376::aid-cncr2820400153>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tabbane F, El May A, Hachiche M, Bahi J, Jaziri J, Cammoun M, Mourali N. Breast cancer in women under 30 years of age. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1985;6:137–144. doi: 10.1007/BF02235745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mourali N, Muenz LR, Tabbane F, Belhassen S, Bahi J, Levine PH. Epidemiologic features of a rapidly progressing breast cancer in Tunisia. Cancer. 1980;46:2741–2746. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19801215)46:12<2741::aid-cncr2820461234>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa J, Webber BL, Levine PH, Muenz L, O’Connor GT, Tabbane F, Belhassen S, Kamaraju LS, Mourali N. Histopathological features of rapidly progressing breast carcinoma in Tunisia: A study of 94 cases. Int Cancer. 1982;30:35–37. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910300107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.El Saghir NS, Shamseddine AI, Geara F, Bikhazi K, Rahal B, Salem ZMK, Taher A, Tawil A, El Khatib Z, Abbas J, Hourani M, Seoud M. Age distribution of breast cancer in Lebanon: Increased percentages and age adjusted incidence rates of younger-aged groups at presentation. J Med Lib. 2002;50:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Saghir NS, Adib S, Mufarru A, Kahwaji S, Taher A, Issa P, Shamseddine AI. Cancer in Lebanon: Ananlysis of 10220 cases from the American University of Beirut medical center. Leb Med J. 1998;46:4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdel_rahman HA, Moustafa R, Shoulah ARS, Wassif OM, Salih MA, El-Gendy SD, Abdo AS. An epidemiological study of breast cancer in greater Cairo. Health Assoc. 1993;68(1–2):119–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soliman A, Bondy ML, Raouf AA, Makram MA, Johnston DA, Levin B. Cancer mortality rates in Menofeia, Egypt: comparison with US mortality rates. Cancer Cases and Control. 1999;10:345–347. doi: 10.1023/a:1008968701313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Freedman LS, Edwards BK, Ries LAG, Young JL. Cancer incidence in four member countries (Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, and Jordan) of the Middle East cancer consortium (MECC) compared with US SEER. National Cancer Institute; Bethesday, MD: NIH Pub. No. 06-5873. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wayne State University College of Urban, Labor, and Metropolitan Affairs. Census: Ethnic profile of Arab and Chaldean populations in metropolitan Detroit 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarts KL, Kulwicki A, Weiss LK, Fakhouri H, Sakr W, Kau G, Severson RK. Cancer among Arab Americans in the metropolitan Detroit area. Ethnicity & Disease. 2004;14:141–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parkin DM, Whelan SL, Ferlay J, Teppo L, Thomas DB, editors. Cancer incidence in five continents Vol. VIII. International Agency for Research in Cancer. Lyon; France: IARC Scientific Publication No. 155. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smigal C, Jemal A, Ward E, Cokkinides V, Smith R, Howe HL, Thun M. Trends in breast cancer by race and ethnicity: Update 2006. A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2006;56:168–183. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.3.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polite B, Olopade O. Breast cancer and race: A rising tide does not lift all boats equally. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 2005;48(1):S166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Newman L. Breast cancer in African-American women. Oncologist. 2005;10:1–14. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.10-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chlebowshi RT, Chen Z, Anderson GL, Rohan T, Aragaki A, Lane D, Dolan NC, Paskett ED, McTiernan A, Hubbell A, Adams-Campvell LL, Prentice R. Ethnicity and breast cancer: Factors influencing differences in incidence and outcomes. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(6):439–448. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hance KW, Anderson WF, Devesa SS, Young HA, Levine PH. Trends in inflammatory breast carcinoma incidence and survival: The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program at the National Cancer Institute. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97(13):966–975. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.UN News Service 2007. UN officials lauds US decision to shelter 7,000 of the most vulnerable Iraqi refugees. 2007 Feb 15; http://www.un.org/apps/news/printnewsAr.asp?nid=21585.

- 23.Karoub J. ABC News. Detroit expects half of Iraqi refugees. 2008 http://abcnews.go.com/print?id=3233636.