Abstract

Atoh1, a basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor, plays a critical role in the differentiation of several epithelial and neural cell types. We found that β-catenin, the key mediator of the canonical Wnt pathway, increased expression of Atoh1 in mouse neuroblastoma cells and neural progenitor cells, and baseline Atoh1 expression was decreased by siRNA directed at β-catenin. The up-regulation of Atoh1 was caused by an interaction of β-catenin with the Atoh1 enhancer that could be demonstrated by chromatin immunoprecipitation. We found that two putative Tcf-Lef sites in the 3′ enhancer of the Atoh1 gene displayed an affinity for β-catenin and were critical for the activation of Atoh1 transcription because mutation of either site decreased expression of a reporter gene downstream of the enhancer. Tcf-Lef co-activators were found in the complex that bound to these sites in the DNA together with β-catenin. Inhibition of Notch signaling, which has previously been shown to induce bHLH transcription factor expression, increased β-catenin expression in progenitor cells of the nervous system. Because this could be a mechanism for up-regulation of Atoh1 after inhibition of Notch, we tested whether siRNA to β-catenin prevented the increase in Atoh1 and found that β-catenin expression was required for increased expression of Atoh1 after Notch inhibition.

Introduction

Progenitor cells in several tissues require the basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH)3 transcription factor, Atoh1, for their development into mature neurons or epithelial cells (1, 2). Upstream regulators of Atoh1 are likely to have an important role in the regulation of development in the central and peripheral nervous systems and in the intestinal epithelium, all of which rely on Atoh1 for differentiation. This finding was clear from the analysis of an Atoh1-null mouse, which lacks many of the cell types of the intestinal epithelium, and has incomplete development of cerebellar and spinal neurons and a complete lack of inner ear hair cells (1). The expression of bHLH transcription factors is partly regulated by components of the Notch pathway (3–5), but these may be only a part of the complex regulatory circuits governing the timing and amount of bHLH transcription factor expression as well as the tissue specificity of expression. The Wnt pathway plays a key role in early development of several of these tissues, including the intestinal epithelium and the inner ear (6–11), and is thus a potential candidate for upstream signaling leading to Atoh1 expression. Indeed, disruption of Wnt signaling prevents intestinal epithelial differentiation to mature cell types and is accompanied by decreased expression of Atoh1 (8).

In a search for genes that affected Atoh1 expression, a number of genes were tested for their effect on Atoh1 expression by screening of an adenoviral library that allowed us to express the genes in various cell types. One such gene was β-catenin, the intracellular mediator of the canonical Wnt pathway. Its overexpression in neural progenitor cell types increased activity of a reporter construct containing GFP under the control of one of the Atoh1 enhancers (12). Atoh1 has a 1.7-kb enhancer 3′ of its coding region, which is sufficient to direct expression of a heterologous reporter gene in several Atoh1 expression domains in transgenic mice (13). A region with high homology is present in the human gene (13).

Previous studies had shown that Atoh1 suppression was controlled by Notch signaling4 but did not identify the factors that increased Atoh1 after Notch inhibition. We found that β-catenin expression was increased after inhibition of Notch signaling and that this increase accounted for the effect of Notch inhibitors on Atoh1 expression. This indicated that expression of β-catenin was normally prevented by active Notch signaling and that β-catenin occupied a position upstream of Atoh1 in these cells. We found that β-catenin bound to the Atoh1 enhancer along with Tcf-Lef transcriptional co-activators, indicating that it directly affected Atoh1 expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

Neuro2a cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum, 2 mm Glutamax, and penicillin (100 units/ml)/streptomycin (100 μg/ml). ROSA26 mouse embryonic stem cells (15) and Pofut1−/− and Pofut1+/+ embryonic stem cells (16) were grown in KO-DMEM (Invitrogen) supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum, 100 μm non-essential amino acids, 55 μm β-mercaptoethanol, 2 mm Glutamax, 12 ng/ml LIF (Chemicon), penicillin (100 units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). The cells were dissociated and cultured in suspension in DMEM supplemented with N2 (Invitrogen) to generate nestin-positive neural progenitors (17). Mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) were isolated from human bone marrow cells as described (18). The cells were expanded once before use and cultured in MEM-α supplemented with 9% horse serum, 9% fetal calf serum, and penicillin (100 units/ml) and streptomycin (100 μg/ml).

Cells were treated with a γ-secretase inhibitor (DAPT, N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl-l-alanyl)]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester, Calbiochem-EMD Bioscience) or a GSK3β inhibitor, (SB415286, Sigma). The compounds were stored as 40 mm stock in DMSO at −20 °C and added at the concentrations given in the text. Wnt3a-conditioned medium was harvested from L-Wnt3a cells (from ATCC, CRL-2647), which were stably transfected with a Wnt3a expression vector and secrete biologically active Wnt3a protein. Control conditioned medium harvested from the parental cell line L (from ATCC, CRL-2648) was used in experiments involving the Wnt3a-conditioned medium. L cells and L-Wnt3a cells were culture in DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum with supplement of 0.4 mg/ml G-418 for L-Wnt3a cells. The conditioned medium was harvested according to the ATCC protocol, sterile-filtered, and stored at −20 °C until use.

Plasmid Constructs and Site-directed Mutagenesis

Atoh1-Luc with the Atoh1 3′ enhancer controlling expression of firefly luciferase (Luc) was described previously.5 Site-directed mutagenesis was performed using the QuikChange® II site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Atoh1-Luc was denatured and annealed to the oligonucleotide primers, TAT CAC CCA AAC AAA tcc gGA GTC AGC ACT TCT T (296–329)/CCC AGG CAA GGA GTC ACC CCC gcg acg TCT GGC TCC TAA CTG AAA AAG (945–992), with the mutations in Tcf-Lef binding sites (lowercase) underlined in the primers. Following temperature cycling, circular DNA was generated from the template vector containing the incorporated mutated Tcf-Lef binding sites using PfuTurbo DNA polymerase, and methylated, parental DNA was digested with Dpn1 endonuclease. Finally the circular, nicked dsDNA was transformed into competent cells for repair.

Gene Silencing and Transfection

siRNAs for silencing of Atoh1 (NM_007500, NM-005172, gca acg uua ucc cgu ccu u UAA CAG CGA UGA UGG CAC A) and β-catenin (NM_007614, NM_001904, GCG CUU GGC UGA ACC AUC AUU, GUG AAA UUC UUG GCU AUU AUU) were obtained from Dharmacon. The more efficient of two siRNA sequences for gene silencing based on quantitative PCR was chosen for each gene. The siRNA (200 nm) was combined with siRNA transfection reagent GeneSilencerTM (5 μl/ml; Gene Therapy Systems) and incubated with the cells for 16 h. Cells were harvested at 48 h. Non-targeting siRNA was transfected in parallel as a control. Transfection efficiency was determined with the fluorescent-labeled non-targeting siRNA. Cells were counted on an epifluorescent microsope (Axioskop 2 Mot Axiocam; Zeiss) and analyzed with a Metamorph Imaging System. Real-time RT-PCR was performed after exposure to the targeting siRNA and the non-targeting siRNA to confirm gene silencing.

Cells to be used for the measurement of gene expression were seeded onto 10-cm dishes and transfected with Atoh1 (18), GFP, control pcDNA3 vector, Notch intracellular domain (NICD) (20), β-catenin (21), or dominant-negative Tcf4 expression vector (22) using 5 μg of DNA per 15 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) in 5 ml of opti-MEM for 106 cells seeded. Transfection was carried out for 4 h, and after washing, followed by incubation with medium. Cells were harvested at 24 h.

RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from cultured cells using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and 1 μg of RNA was subjected to RT-PCR with SuperTransciptTM III and TaqDNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). The primer sequences were as follows: Atoh1, forward, AGA TCT ACA TCA ACG CTC TGT C; reverse, ACT GGC CTC ATC AGA GTC ACT G (449bp); GAPDH, forward, AAC GGG AAG CCC ATC ACC; reverse, CAG CCT TGG CAG CAC CAG (442bp); β-catenin, forward, ATG CGC TCC CCT CAG ATG GTG TC; reverse, TCG CGG TGG TGA GAA AGG TTG TGC (113bp). Annealing temperature and cycles were optimized for each primer. PCR primers for real-time PCR of Atoh1 and S18 were ordered from Applied Biosystems, and PCR was performed in a Perkin Elmer ABI PRISMTM 7700 Sequence Detector (PE Applied Biosystems).

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation

In brief, 5 × 107 Neuro2a cells (175-cm2 culture flasks) were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde in DMEM for 10 min, followed by 5 min at 37 °C in formaldehyde saturated with glycine. The cells were harvested and washed in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and pelleted for 10 min at 720 × g at 4 °C. The nuclei were released in a Dounce homogenizer in PBS containing protease inhibitors and collected at 4 °C by centrifugation at 2,400 × g. Sheared chromatin was collected in the supernatant by centrifugation (8,000 × g at 4 °C for 10 min) after treatment of the nuclei with the enzymatic mixture from a ChIP-ITTM Express kit (Active Motif) for 10 min at 37 °C. An aliquot (10 μl) of the sheared DNA was saved as the input sample for PCR, and the rest (3 × 80 μl) was split for immunoprecipitation using 1 μg of mouse anti-β-catenin antibody (Upstate, 05-601, 1:100), mouse anti-LEF-1 antibody (Sigma L7901), or nonimmune mouse serum (Sigma). The precipitated chromatin was recovered after reversing cross-links, and the proteins were digested with proteinase K. Target Atoh1 regulatory DNA (AF218258) was amplified by PCR using primers: forward, ACG TTT GGC AGC TCC CTC TC; reverse, ATA GTT GAT GCC TTT GGT AGT A (33-272); forward, ATT CCC CAT ATG CCA GAC CAC; reverse, GGC AAA GAC AGA ATA TAA AAC AAG (148-434); forward, AAT CGG GTT AGT TCT TTG; reverse, ACT CCC CCT CCC TTT CTG GTA (349-609); forward, CAC GGG GAG CTG AAG GAA G; reverse, TTT TAA GTT AGC AGA GGA GAT GTA (501-742); forward, CTG AGC CCC AAA GTT GTA ATG TT; reverse, TGG GGT GCA GAG AAG ACT AAA (675-939); forward, ACC CCA GGC CTA GTG TCT CC; reverse, TGC CAG CCC CTC TAT TGT CAG (926-1161); forward, GTG GGG GTA GTT TGC CGT AAT GTG; reverse, GGC TCT GGC TTC TGT AAA CTC TGC (1094-1367).

DNA Pull-down Assay

Nuclei were isolated from 106 Neuro2a cells following mechanical disruption with a 20-gauge needle. Proteins were extracted from nuclei in 200 μl of radioimmune precipitation assay buffer (RIPA) (Sigma) with fresh proteinase inhibitors (2 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; protease inhibitor mixture, Sigma) at 4 °C for 60 min. Chromatin DNA was pelleted at 14,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C, and the nuclear lysate in the supernatant was collected. Biotin-labeled DNA probes (0.3 μg) with or without 10 μg of unlabeled DNA probe were incubated with 40 μl of nuclear lysate with proteinase inhibitors for 30 min at room temperature in binding buffer (10 mm Tris, 50 mm KCl, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 5% glycerol, pH 7.5, 40 mm 20 mer poly A and poly C). Probes used were (mutations shown in lowercase): ATC ACC CAA ACA AAC AAA GAG TCA GCA CTT (297–326); ATC ACC CAA ACA cAT Acg aAG TCA GCA CTT (mutant 297–326); GTT AGG AGC CAG AAG CAA AGG GGG TGA CTC (956–985); GTT AGG AGC CAG AgG atc gtG GGG TGA CTC (mutant 956–985). Probe-bound proteins were collected with streptavidin magnetic beads (50 μl, Amersham Biosciences). Precipitated proteins were washed 5× with binding buffer and boiled in 50 μl of 2× sample buffer, and the supernatant was collected for Western blotting with anti-β-catenin antibody and anti-Lef-1-Tcf antibody.

Western Blotting

Proteins extracted with RIPA buffer from whole cells or after nuclear fractionation were separated on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen) and electrotransferred to 0.2-μm nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were probed with sheep anti-Lef-1-Tcf antibody (Sigma L4270), rabbit anti-β-catenin antibody (Sigma C2206), rabbit anti-Atoh1 (ABR, PA1–17101), mouse anti-unphosphorylated β-catenin (Millipore, 35222), mouse anti-phosphorylated GSK3β Y216 (BD 612312), or mouse anti-GSK3β (BD 610201) followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-sheep (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-rabbit (Chemicon), or anti-mouse (Chemicon) antibodies. The blots were processed with ECLTM (Amersham Biosciences) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The membranes were stripped with RestoreTM Western blot stripping buffer (Thermo Scientific), followed by probing with mouse anti-β-actin antibody (Sigma A2228) and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (Sigma).

Luciferase Assay

105 Neuro2a cells were seeded into a 24-well plate 1 day before transfection. 0.125 μg of Atoh1-luciferase reporter construct, CBF1-luciferase reporter construct (23), 0.125 μg of TOPFlash, or FOPFlash (Addgene), or 0.125 μg of Renilla-luciferase construct with or without 0.25 μg of β-catenin expression construct were mixed with 0.5 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 in 0.125 ml of opti-MEM and incubated with the cells for 4 h. Cells were lysed after 48 h, and luciferase activity was measured using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) in a TD-20/20 Luminometer (Turner Designs).

RESULTS

Overexpression of β-Catenin Up-regulates Atoh1 Expression

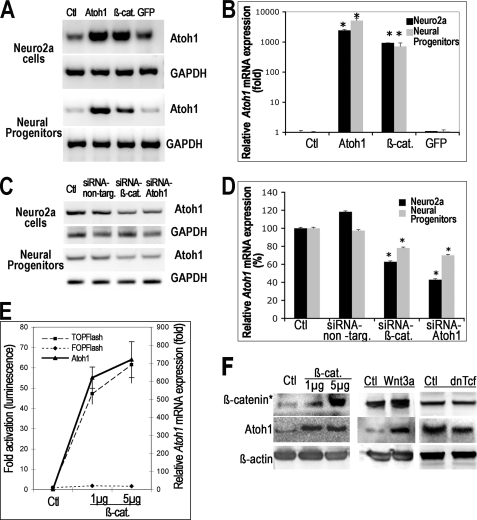

The effect of β-catenin overexpression and silencing on Atoh1 levels was measured in two neural cell types, a neuroblastoma cell line and neural progenitors derived from embryonic stem cells.

Overexpression of β-catenin in Neuro2a cells increased expression of Atoh1 mRNA based on RT-PCR (β-cat, Fig. 1A). Expression of Atoh1 was also up-regulated in neural progenitors after overexpression of β-catenin (β-cat, Fig. 1A). The increase was significant for both Neuro2a cells (871.3 ± 141.3) and neural progenitors (741.2 ± 218.2) as determined by quantitative RT-PCR compared with cells transfected with a GFP vector without β-catenin (1.1 ± 0.1) or untreated cells (1 ± 0.2) (p < 0.01, Fig. 1B). Atoh1 expression was also increased after transfection with Atoh1 cDNA as a control (Atoh1, Fig. 1, A and B).

FIGURE 1.

β-Catenin overexpression increased Atoh1 mRNA levels, and β-catenin silencing decreased Atoh1 mRNA levels. A, analysis of Atoh1 mRNA expression by RT-PCR showed that transfection of β-catenin (β-cat) into both Neuro2a cells and neural progenitors increased Atoh1 mRNA compared with untransfected cells (Ctl), whereas GFP transfection did not increase Atoh1 mRNA. Atoh1 transfection (Atoh1) was used as a positive control, and GAPDH was used as an internal control. B, increase in Atoh1 expression was quantified by real-time PCR in Neuro2a cells and neural progenitors from two independent experiments (each experiment in triplicate). The cells were transfected with either β-catenin (β-cat.) or Atoh1 (Atoh1) as positive controls or GFP (GFP) as a negative control. Atoh1 levels are expressed relative to untreated control cells (Ctl) and normalized to S18, a housekeeping gene. The increase in Atoh1 expression relative to the control was significant for both cell types transfected with β-catenin or Atoh1 (marked by asterisk). C, Atoh1 mRNA expression was analyzed by RT-PCR in Neuro2a cells and neural progenitors treated with siRNA. Atoh1 expression was decreased in the cells treated with β-catenin siRNA (siRNA-β-cat.) compared with non-targeting siRNA (siRNA-non-targ.) or no siRNA (Ctl). Cells treated with Atoh1 siRNA (siRNA-Atoh1) were used as a positive control. D, decrease in Atoh1 expression was quantified by real-time PCR from two independent experiments (each experiment in triplicate). The cells were transfected with β-catenin siRNA (siRNA-β-cat) or non-targeting siRNA (siRNA-non-targ). Atoh1 levels are expressed relative to untreated control cells (Ctl) and normalized to S18. Significant decreases in expression of Atoh1 are indicated by asterisks. E, activation of Tcf-Lef-mediated transcription was measured by TOPFlash luciferase reporter, and increased Atoh1 expression was quantified by real-time RT-PCR. Transfection of β-catenin (1 μg/ml or 5 μg/ml) increased TOPFlash activity (TOPFlash, dashed line) and Atoh1 mRNA expression in neural progenitor cells. FOPFlash (FOPFlash, dotted line), which contains mutant Tcf/Lef-binding sites remained unchanged in the cells transfected with β-catenin. F, nuclear fraction of unphosphorylated β-catenin and Atoh1 was examined by Western blotting in neural progenitors transfected with β-catenin, treated with Wnt3a, or transfected with dominant-negative Tcf4 (dnTcf). Overexpression of β-catenin increased the level of activated nuclear β-catenin (β-catenin*) and Atoh1. Wnt3a-conditioned medium compared with control conditioned medium (Ctl) also increased the level of active nuclear β-catenin and Atoh1. Conversely, overexpression of dominant-negative Tcf4 decreased the level of Atoh1.

Atoh1 expression was decreased by Atoh1 siRNA (siRNA-Atoh1, Fig. 1C), used as a positive control, but not by non-targeting siRNA (siRNA-non-targ, Fig. 1C) or no siRNA (Ctl, Fig. 1C). The extent of the decrease in Atoh1 mRNA after silencing with siRNA directed to Atoh1 was 57 ± 1.4% (Fig. 1D). β-Catenin siRNA decreased β-catenin expression by 62 ± 6% as determined by quantitative RT-PCR. Silencing β-catenin expression with siRNA directed to β-catenin decreased Atoh1 mRNA levels in Neuro2a cells and neural progenitors based on RT-PCR (Fig. 1C). Down-regulation of β-catenin decreased Atoh1 expression by 37.2 ± 1.0% in Neuro2a cells and 21.8 ± 0.5% in neural progenitors. The decrease in Atoh1 expression determined by quantitative RT-PCR after treatment with β-catenin siRNA was significant (p < 0.01, Fig. 1D).

The level of β-catenin activity as measured by the TOPFlash reporter, which contains multiple binding sites for β-catenin complexed to Tcf-Lef co-activators, was proportional to the concentration of β-catenin cDNA (Fig. 1E), and the increase in TOPFlash signal correlated with an increased expression of Atoh1. Increased amounts of β-catenin cDNA also raised the level of the active fraction of nuclear β-catenin, which is recognized by an antibody (24) to the unphosphorylated form (β-catenin*) in correlation with Atoh1 (Fig. 1F). Wnt3a-conditioned medium (Wnt3a) also resulted in parallel increases in the level of both nuclear unphosphorylated β-catenin and Atoh1, whereas overexpression of dominant-negative Tcf4 (dnTcf), which lacks the β-catenin binding site, decreased the level of Atoh1. These experiments demonstrated a correlation between the level of expression of β-catenin and Atoh1.

β-Catenin Binds to Tcf-Lef Sites within the Atoh1 Enhancer and Binding Leads to Activation of the Enhancer

To define the binding sites on the mouse Atoh1 enhancer, we searched the 3′ enhancer sequence. The software indicated two potential binding sites for β-catenin in combination with Tcf-Lef transcriptional co-activators at 309–315 and 966–972 (AF218258). To investigate whether β-catenin in combination with Tcf-Lef factors has a direct interaction with regulatory regions of the Atoh1 gene, we analyzed the DNA binding to β-catenin and Tcf-Lef by chromatin immunoprecipitation. Sheared and cross-linked chromatin was immunoprecipitated with β-catenin or Tcf-Lef antibodies, and the precipitated chromatin was amplified by PCR using primers covering the entire 1.3-kB sequence in overlapping segments. β-Catenin and Tcf-Lef antibody immunoprecipitated DNA at the 5′- and 3′-ends of the 1.3-kB sequence indicating that DNA in the regions had an affinity for both of the proteins (Fig. 2, β-catenin and Tcf/Lef). The intermediate sequences did not display this affinity suggesting that this sequence contained binding sites at its ends as predicted. These sequences were not amplified by PCR from chromatin immunoprecipitated with nonimmune IgG (Fig. 2, serum), whereas the same DNA fragments were co-precipitated by β-catenin and Tcf-Lef antibodies. This shows that these proteins bound to the same sequences of DNA. The precise localization of the binding sites could not be ascertained from the PCR data because the shearing of the DNA is variable, and, despite repeated attempts, the variable lengths of sheared DNA led to different patterns of bands from the overlapping primers.

FIGURE 2.

Direct binding of β-catenin to the Atoh1 enhancer through Tcf-Lef. Binding of β-catenin to the Atoh1 enhancer was examined by ChIP. Chromatin was cross-linked in Neuro2a cells followed by precipitation with nonimmune IgG, β-catenin antibody, or Tcf-Lef antibody. The sheared Atoh1 enhancer fragments were amplified from the precipitated chromatin. The primers for DNA at the two ends of the Atoh1 enhancer, including the predicted Tcf-Lef binding sites (148–434 and 928–1123) and adjacent fragments, were found to amplify DNA from the immunoprecipitate. In a control, chromatin precipitated with nonimmune IgG (serum) did not contain DNA that could be amplified with these primers. Input refers to DNA without antibody precipitation. The extent of amplification of the fragments varied as a function of the extent of shearing of the chromatin.

To determine the precise sequences that had an affinity for β-catenin and Tcf-Lef we performed DNA pull-down assays with two biotin-labeled oligonucleotides probes, covering bases 297–326 and 956–985 of the Atoh1 sequence, which contained the predicted Tcf-Lef binding sites and surrounding nucleotides. Incubation of the probes with nuclear lysate from Neuro2a cells was followed by precipitation with streptavidin beads. By Western blotting of the proteins interacting with the probes, both β-catenin and Tcf-Lef could be detected (Fig. 3A, probe 309 and probe 966). The binding of β-catenin and Tcf-Lef to the probes was reduced by competition with unlabeled probes (Fig. 3A, comp 309 and comp 966), and mutation of the predicted binding sites reduced binding in both cases (Fig. 3A, mutant 309 and mutant 966). The correlation between β-catenin binding and Tcf-Lef binding suggested that the proteins were involved in a complex, and this agreed with the ChIP data showing that both proteins could be precipitated from the binding sites in the native DNA. This experiment also suggested that both of the potential binding sites on the Atoh1 enhancer bound to the complex of Tcf-Lef with β-catenin.

FIGURE 3.

β-Catenin interacts with the Atoh1 3′ enhancer in a complex with Tcf-Lef. A, nuclear lysate from Neuro2a cells was incubated with biotin-labeled DNA probes corresponding to enhancer sequence 297–326 (probe 309) and 956–985 (probe 966), which contained two predicted β-catenin/Tcf-Lef binding sequences, and Atoh1 enhancer-binding proteins were collected with magnetic beads coupled to streptavidin. Proteins were analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies specific for β-catenin and Tcf-Lef. β-Catenin (β-catenin) was found in the bead-eluted proteins (probe 309 and probe 966), indicating an interaction with the probes; binding was inhibited by competition with excess unlabeled probes (comp 309 and comp 966). Binding was inhibited when predicted β-catenin/Tcf-Lef binding sequences were mutated in the probes (mutant 309 and mutant 966). Tcf-Lef was also found in this fraction (Tcf/Lef) indicating formation of a complex involving Tcf-Lef factors and β-catenin. B, expression of Atoh1 in untransfected Neuro2a cells and neural progenitors (Ctl) was increased in the same cells transfected with 1 μg/ml β-catenin (β-cat). The level of Atoh1 was decreased in a dose-dependent manner when cells were co-transfected with dominant-negative Tcf4 (β-cat + dn Tcf). The Atoh1 levels were analyzed by real-time PCR in two independent experiments (each experiment in triplicate). The asterisks mark significant differences in Atoh1 expression compared with control.

The expression of Atoh1 in Neuro2a cells transfected with β-catenin (1 μg/ml) or co-transfected with dominant-negative Tcf4 was analyzed by real-time PCR from two independent experiments (each experiment in triplicate). The increase in Atoh1 expression after overexpression of β-catenin was inhibited in reverse proportion to the concentration of dominant-negative Tcf4 (p < 0.01, Fig. 3B), and the extent of inhibition was nearly complete at the higher level, indicating that a complex with Tcf-Lef was required for activation of Atoh1 by β-catenin.

To determine whether the two β-catenin binding sites on the Atoh1 enhancer increased the functional activity of the Atoh1 enhancer, we constructed Atoh1 enhancer-reporter genes with an intact or mutated Atoh1 3′ enhancer. Each of the β-catenin binding sites in the Atoh1 enhancer were mutated, alone or in combination, in a luciferase reporter construct (Fig. 4). We found that overexpression of β-catenin had no effect on a luciferase construct without the Atoh1 enhancer (Fig. 4, Luc), but transfection of β-catenin at the same time as the reporter containing the native Atoh1 enhancer increased reporter gene expression (Fig. 4, Atoh1-Luc). Up-regulation of Atoh1 enhancer activity was reduced when the first β-catenin binding site was mutated (Fig. 4, Atoh1-Luc, mutant 309). β-Catenin-mediated up-regulation of the Atoh1 reporter was also reduced when the second β-catenin binding site in the Atoh1 enhancer was mutated (Fig. 4, Atoh1-Luc, mutant 966). Double mutation of the binding sites completely abolished β-catenin-mediated up-regulation (Fig. 4, Atoh1-Luc, 2X mutant) (p < 0.01). This indicated that β-catenin binding to the Atoh1 enhancer at the binding sites at 309–315 and 966–972 increased activity of the enhancer. The absolute level of the increase likely results from this activity combined with subsequent auto-activation of the 3′ enhancer caused by binding of Atoh1 to its own enhancer (25). To determine the contribution of this auto-feedback loop, we directly transfected the cells with Atoh1 in combination with the Atoh1-luciferase reporter. Atoh1 overexpression up-regulated both unaltered and double mutant Atoh1 reporter about 1.5-fold, indicating that auto-feedback did not account for the level of activation found with β-catenin, but could add to the reporter activity by binding independently to the Atoh1 enhancer.

FIGURE 4.

β-Catenin binding to the Atoh1 enhancer at a Tcf-Lef binding site accounts for the functional effect of β-catenin on Atoh1 expression. Atoh1 enhancer was used to drive luciferase expression in the pGL-3 reporter vector (Atoh1-Luc). The β-catenin binding sites on the Atoh1 enhancer were mutated individually (mutant 309; mutant 966) or both binding sites were mutated (2X mutant). The reporter construct or mutant reporters were co-transfected into Neuro2a cells with overexpression of β-catenin. Overexpression of β-catenin (black bars) activated reporter expression up to 4-fold (Atoh1-Luc), whereas β-catenin overexpression had no effect on expression of the pGL-3 construct in the absence of the Atoh1 enhancer (Luc, gray bars). Mutant 309 (Atoh1-Luc, mutant 309) decreased β-catenin-mediated activation of the enhancer 53% (from 3.9–1.84-fold), whereas mutant 966 (Atoh1-Luc, mutant 966) decreased activation of the enhancer 26% (from 3.9–2.91-fold). Each treatment was in triplicate, and the values shown are from two independent experiments with significant changes indicated by an asterisk (compared with the unmutated Atoh1 reporter). The double mutation (Atoh1, 2X mutant) completely abolished activation of the enhancer. Neither single nor double mutation in the absence of β-catenin had an effect on reporter expression (gray bars).

Increased Expression of Atoh1 after Notch Inhibition Is Partly Caused by β-Catenin Expression

Because Notch also regulates Atoh1 expression, we sought to determine whether increased expression of Atoh1 after treatment with a γ-secretase inhibitor3 to inhibit Notch signaling was affected by β-catenin.

To observe the effect of a γ-secretase inhibitor, we assessed expression of β-catenin in bone marrow-derived MSCs, cells that were previously shown to have increased Atoh1 expression after Notch inhibition.3 Inhibition of Notch signaling by the γ-secretase inhibitor and up-regulation by transfection of Notch intracellular domain was confirmed in these cells with a CBF-1 luciferase reporter (data not shown). The expression of β-catenin was increased in MSCs treated with a γ-secretase inhibitor (Fig. 5A, DAPT; quantification of these results is shown in the supplemental data). Atoh1 expression was increased by the inhibition of Notch signaling in the cells that had increased β-catenin (Fig. 5A). A GSK3β inhibitor (GSKi) also increased Atoh1, consistent with its ability to increase β-catenin in these cells (Fig. 5A).

FIGURE 5.

Increased expression of Atoh1 after Notch inhibition is partly caused by β-catenin expression. A, to observe the effect of Notch inhibition we assessed expression of β-catenin and Atoh1 in bone marrow-derived MSCs by Western blot. The expression of β-catenin was increased in MSCs treated with a γ-secretase inhibitor, DAPT, at 10 μm and 50 μm. Atoh1 expression was also increased (Atoh1). Treatment of the cells with GSK3β inhibitor (GSKi) also increased the expression of β-catenin and Atoh1. B, effect of two siRNAs to β-catenin (siRNA-β-cateninA; siRNA-β-cateninB) was evaluated by quantitative RT-PCR. Treatment with the siRNAs decreased the expression of β-catenin in a dose-dependent manner; non-targeting siRNA (siRNA-non-targeting) had no significant effect. C, to determine whether increased expression of Atoh1 seen after Notch inhibition was related to β-catenin expression the levels of β-catenin and Atoh1 were examined by Western blot. The elevated β-catenin after DAPT treatment (β-catenin) was decreased by siRNA to β-catenin. The increased expression of Atoh1 with DAPT could also be decreased by blocking β-catenin expression with the siRNA but not with non-targeting siRNA. D, we tested the effect of disrupting the Notch pathway using Pofut1−/− cells that have a mutation that prevents Notch signaling. Atoh1 expression was higher in these cells and the γ-secretase inhibitor could not further increase Atoh1 expression as determined by quantitative RT-PCR (pofut-), compared with wild-type cells (Rosa 26 and pofut+). The deceased level of β-catenin using siRNA (siRNA-β-catenin) resulted in a decrease in expression of Atoh1 (pofut-), confirming that β-catenin signaling under conditions of decreased Notch signaling was partly responsible for the increased level of Atoh1. The decrease in Atoh1 expression in cells treated with β-catenin siRNA was significant compared with the control and DAPT treatment. E, inhibition of Notch activity with DAPT (DAPT) increased activated β-catenin (β-catenin*) and Atoh1 expression. Disruption of β-catenin-mediated transcription by overexpression of dominant-negative Tcf4 (dn Tcf) reversed the increase of Atoh1 expression in cells treated with the Notch inhibitor. Overexpression of Notch intracellular domain (Notch) decreased activated β-catenin and Atoh1 expression. Activation of β-catenin-mediated transcription by Wnt3a rescued the decrease of Atoh1 expression in cells with elevation of Notch activity. F, inhibition of Notch with DAPT decreased phosphorylated GSK3β (GSK3β*Y216), increased activated β-catenin (β-catenin*), and increased Atoh1 expression. Conversely, activation of Notch intracellular domain increased phosphorylated GSK3β, decreased activated β-catenin, and reduced Atoh1 expression. The total GSK3β remained unchanged.

To determine whether β-catenin expression was related to increased expression of Atoh1 seen after treatment of these cells with a γ-secretase inhibitor, we blocked β-catenin expression with siRNA and measured the influence on Atoh1. Incubation of MSCs with siRNA to β-catenin decreased β-catenin expression as much as 70% based on quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5B). The siRNA prevented the increase in β-catenin that could be seen after treatment with a γ-secretase inhibitor (Fig. 5C) and decreased the level of Atoh1 expression (Fig. 5C).

We tested the effect of disrupting the Notch pathway by a method other than a γ-secretase inhibitor. Comparison of Atoh1 in wild-type neural progenitor cells and Pofut1−/− cells that have a mutation that prevents Notch signaling showed that Atoh1 expression was higher in the cells that lacked Notch signaling (Fig. 5D), and a γ-secretase inhibitor, which increased Atoh1 expression in control cells, did not further increase Atoh1 expression in Pofut−/− cells, as determined by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 5D). To see if increased Atoh1 was caused by the higher expression level of β-catenin, we blocked β-catenin expression with siRNA. The deceased level of β-catenin resulted in a decrease in expression of Atoh1 (Fig. 5D), confirming that β-catenin signaling was partly responsible for the increased level of Atoh1 found under conditions of Notch blockage.

Disruption of β-catenin-mediated transcription by overexpression of dominant-negative Tcf (dnTcf) reversed the increase of Atoh1 expression in cells treated with the Notch inhibitor (Fig. 5E). Conversely, whereas β-catenin and Atoh1 expression were diminished in cells after elevation of Notch activity, activation of β-catenin-mediated transcription by Wnt3a (Wnt3a) returned the expression of Atoh1 to control levels.

Notch could influence the level of β-catenin by regulation of GSK3β activity. Inhibition of Notch decreased the level of phosphorylated GSK3β (GSK3β*Y216) and increased the nuclear fraction of unphosphorylated β-catenin (Fig. 5F, β-catenin*), resulting in increased Atoh1 and suggesting that Notch could down-regulate β-catenin by increasing its degradation via increased GSK3β activity. Activation of Notch increased phosphorylated GSK3β but left total GSK3β unchanged, and this appeared to correlate with a decrease in unphosphorylated β-catenin and a reduction in Atoh1 expression (Fig. 5F). Thus, Notch regulated GSK3β activity and thereby controlled the level of β-catenin and Atoh1.

DISCUSSION

Multiple influences control the timing of Atoh1 expression, a key factor in development of the nervous system and the maintenance of intestinal epithelial cells. We show here that β-catenin signaling triggers Atoh1 expression by interacting with sites within the 3′ enhancer of the Atoh1 gene. Binding of β-catenin to the enhancer occurred in conjunction with Tcf-Lef co-activators. Putative Tcf-Lef sites found in this regulatory region both displayed an affinity for Tcf-Lef and β-catenin. We found that both sites were critical for full activation of the Atoh1 gene, and this led to increased transcription of Atoh1 from the endogenous gene. Inhibition of Notch signaling, which has previously been shown to induce Atoh1 expression,3 was found to increase β-catenin expression in progenitor cells of the nervous system. β-Catenin expression was required for the increased expression of Atoh1 caused by Notch inhibition because siRNA to β-catenin prevented the increase in Atoh1.

Finding upstream regulators of Atoh1 is a key to understanding its role in cell specification because, once it is activated, Atoh1 transcription is self-perpetuating. This is due to binding of Atoh1 protein to the Atoh1 3′ enhancer (13). Thus, whatever factor first activates Atoh1 transcription has a powerful role. Upstream regulators of Atoh1 have been postulated as initiators of the self-supporting synthesis of Atoh1, but these key activators have not been identified in embryonic development. Although hair cells are absent in the Atoh1 knock-out mouse (1), the Atoh1 promoter is switched on (26), indicating that a mechanism for activation of the gene must exist. β-Catenin could be one of the genes that regulates Atoh1 expression in the embryo. Atoh1 expression was increased by β-catenin interaction with Tcf-Lef sites in the Atoh1 enhancer. β-Catenin expression is first found in the otic placode at embryonic day 8.5 (7, 27), and the first Atoh1 expression during development of the cochlea does not occur until after this time (1). Thus, our data indicate that β-catenin is likely to regulate expression of Atoh1, and the timing of expression in the inner ear is consistent with the possibility that β-catenin stimulates Atoh1 expression in the early embryo.

Because Notch is another key regulator of Atoh1 expression,3 we investigated whether disruption of Notch signaling could lead to alterations in β-catenin that would account for the increased expression of Atoh1. We found that, when released from Notch regulation, β-catenin expression was increased in neural progenitor cells and MSCs. Increased expression of β-catenin was demonstrated after preventing Notch activity with a γ-secretase inhibitor. Notch exerted its effect by a mechanism (28) involving phosphorylation at Tyr-216 of GSK3β, a key enzyme in the regulation of β-catenin activity. The increase in β-catenin resulted in an up-regulation of Atoh1 in these cells. A similar increase was found in cells that carry a mutation that prevents Notch signaling. When the mutant cells were treated with siRNA to β-catenin, a decrease in Atoh1 expression was observed and was also found in normal cells treated with a Notch inhibitor and siRNA to β-catenin, indicating that β-catenin was necessary as a mediator of increased Atoh1 expression after disruption of Notch signaling.

Notch is a negative regulator of Atoh1 expression, but it has not been clear how Atoh1 expression could be initiated. Notch signaling is thought to prevent proneural bHLH transcription factor activity through the inhibitory actions of Hes family members (5). Previous studies have shown that Notch signaling regulates activity of β-catenin and can prevent nuclear localization and up-regulation of β-catenin target genes (29), although other studies have shown contradictory effects of Notch on Wnt signaling. Models in which Notch signaling has been manipulated showed that β-catenin activity was inhibited by Notch in stromal cells from bone marrow (30) and in muscle stem cells (28). These studies concluded that Notch signaling inhibited Wnt signaling by direct action of Hes1 (30) or by activation of GSK3β (28). Activation of GSK3β was the apparent mechanism of Wnt inhibition in this study. Our study agrees with the conclusion that Notch inhibits Wnt signaling in neural progenitors and MSCs and could explain how inhibition of Notch leads to Atoh1 up-regulation. Thus, Notch signaling must be turned down before β-catenin signaling can become dominant and suggests a regulatory hierarchy of Atoh1 expression in which β-catenin is a key mediator that initiates synthesis of Atoh1 after the attenuation of Notch (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

Schematic diagram illustrates regulation of Atoh1 by β-catenin. The positive sign and arrow represent the increased transcription of Atoh1 upon binding of β-catenin-Tcf/Lef to the Atoh1 3′-enhancer. The resulting Atoh1 acts to up-regulate its own expression by binding to the same enhancer. Stimulation by β-catenin accounts for the up-regulation of Atoh1 after Notch inhibition. Atoh1 levels are determined by negative regulation by transcription factors such as Hes1 and 5 when Notch signaling is active.

This hypothesis is supported by previous findings. Blocking Wnt signaling by constitutive expression of Dickopf (8) prevented differentiation of intestinal cells to the secretory cell types of the intestinal epithelium, a phenotype that was similar to that of the Atoh1 knock-out mouse (2). Inhibition of Notch led to increased goblet cell differentiation, which is dependent on β-catenin signaling and Atoh1 expression (11). Overexpression of β-catenin stimulated Atoh1 in lung epithelium where it is not normally expressed (31). Our study for the first time shows that β-catenin directly regulates Atoh1 and provides a mechanism for the previous observation of an effect of β-catenin on expression of the Atoh1 gene.

Other bHLH transcription factors contain regulatory regions for β-catenin binding and have been shown to respond to β-catenin binding by increased expression. Cortical neural progenitor cells exposed to Wnt or transfected with activated β-catenin increased expression of Ngn1 in conjunction with their increased differentiation to neurons (32), and this was shown to be due to direct binding and activation of the Ngn1 promoter by β-catenin. A similar binding and increased activity of the Ngn1 promoter and the Ngn2 enhancer was reported in P19 embryonal carcinoma cells (33). Wnt plays a dual role in progenitor cells that can lead to their proliferation or differentiation. Wnt signaling is required for the expansion of progenitors in the CNS (8, 34). However, Wnt signaling can provide a signal that leads to terminal differentiation of neurons (32, 33, 35, 36) consistent with the activation of bHLH transcription factors as we have demonstrated in neural progenitors.

Unlike the activation of Atoh1 by β-catenin in neural progenitors, Wnt signaling is aberrant in tumor cells and the dependence of Atoh1 expression on Wnt signaling does not follow the normal pattern (2, 8, 19). Expression of Atoh1 protein was decreased in colon tumors despite increased nuclear β-catenin expression, and inhibition of β-catenin signaling increased Atoh1 expression (14). We have found an increase in Atoh1 mRNA expression but not protein expression in human colon cancer cells after overexpression of β-catenin, whereas both Atoh1 mRNA and protein are increased in HEK cells (data not shown). An explanation for this may come from a recent study in which Atoh1 expression in colon cancer cells was found to be decreased because of direct GSK3β-mediated degradation of Atoh1 (19). Clarification of the role of Wnt signaling in Atoh1 expression will be aided by our demonstration that β-catenin binds to the Atoh1 enhancer to activate expression of this key transcription factor.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for generous gifts of reagents and cells: Oksana Berezovska for the NICD expression vector, Eric Fearon for the dominant-negative Tcf4 plasmid, Walter Birchmeier for the β-catenin expression vector, Diane Hayward for the CBF1-luciferase vector, and Pamela Stanley for the Pofut1−/− stem cells. We thank Kevin Jiang for technical assistance.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 DC007174 and P30 DC05209 from the NIDCD and by the Hamilton H. Kellogg and Mildred H. Kellogg Charitable Trust.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental data.

S. J. Jeon, M. Fujioka, and A. S. B. Edge, in preparation.

S. J. Jeon, M. Fujioka, K. I. Seyb, E. R. Schuman, M. L. Michaelis, M. Glicksman, and A. S. B. Edge, in preparation.

- bHLH

- basic helix-loop-helix

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- MSC

- mesenchymal stem cells

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- DAPT

- N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl-l-alanyl)]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester

- GAPDH

- glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bermingham N. A., Hassan B. A., Price S. D., Vollrath M. A., Ben-Arie N., Eatock R. A., Bellen H. J., Lysakowski A., Zoghbi H. Y. (1999) Science 284, 1837–1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Q., Bermingham N. A., Finegold M. J., Zoghbi H. Y. (2001) Science 294, 2155–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bertrand N., Castro D. S., Guillemot F. (2002) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 517–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirata H., Tomita K., Bessho Y., Kageyama R. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 4454–4466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ross S. E., Greenberg M. E., Stiles C. D. (2003) Neuron 39, 13–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clevers H. (2006) Cell 127, 469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohyama T., Mohamed O. A., Taketo M. M., Dufort D., Groves A. K. (2006) Development 133, 865–875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinto D., Clevers H. (2005) Exp. Cell Res. 306, 357–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stevens C. B., Davies A. L., Battista S., Lewis J. H., Fekete D. M. (2003) Dev. Biol. 261, 149–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Es J. H., Jay P., Gregorieff A., van Gijn M. E., Jonkheer S., Hatzis P., Thiele A., van den Born M., Begthel H., Brabletz T., Taketo M. M., Clevers H. (2005) Nat. Cell Biol. 7, 381–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Es J. H., van Gijn M. E., Riccio O., van den Born M., Vooijs M., Begthel H., Cozijnsen M., Robine S., Winton D. J., Radtke F., Clevers H. (2005) Nature 435, 959–963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lumpkin E. A., Collisson T., Parab P., Omer-Abdalla A., Haeberle H., Chen P., Doetzlhofer A., White P., Groves A., Segil N., Johnson J. E. (2003) Gene Expr. Patterns 3, 389–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helms A. W., Abney A. L., Ben-Arie N., Zoghbi H. Y., Johnson J. E. (2000) Development 127, 1185–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leow C. C., Romero M. S., Ross S., Polakis P., Gao W. Q. (2004) Cancer Res. 64, 6050–6057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zambrowicz B. P., Imamoto A., Fiering S., Herzenberg L. A., Kerr W. G., Soriano P. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 94, 3789–3794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stahl M., Uemura K., Ge C., Shi S., Tashima Y., Stanley P. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13638–13651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrales C. E., Pan L., Li H., Liberman M. C., Heller S., Edge A. S. (2006) J. Neurobiol. 66, 1489–1500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeon S. J., Oshima K., Heller S., Edge A. S. (2007) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 34, 59–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tsuchiya K., Nakamura T., Okamoto R., Kanai T., Watanabe M. (2007) Gastroenterology 132, 208–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berezovska O., Jack C., McLean P., Aster J. C., Hicks C., Xia W., Wolfe M. S., Kimberly W. T., Weinmaster G., Selkoe D. J., Hyman B. T. (2000) J. Neurochem. 75, 583–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huelsken J., Vogel R., Erdmann B., Cotsarelis G., Birchmeier W. (2001) Cell 105, 533–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kolligs F. T., Hu G., Dang C. V., Fearon E. R. (1999) Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 5696–5706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hsieh J. J., Henkel T., Salmon P., Robey E., Peterson M. G., Hayward S. D. (1996) Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 952–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Noort M., Weerkamp F., Clevers H. C., Staal F. J. (2007) Blood 110, 2778–2779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helms A. W., Gowan K., Abney A., Savage T., Johnson J. E. (2001) Mol. Cell Neurosci. 17, 671–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fritzsch B., Pauley S., Matei V., Katz D. M., Xiang M., Tessarollo L. (2005) Hear Res. 206, 52–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Riccomagno M. M., Takada S., Epstein D. J. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1612–1623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brack A. S., Conboy I. M., Conboy M. J., Shen J., Rando T. A. (2008) Cell Stem Cell 2, 50–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Proweller A., Tu L., Lepore J. J., Cheng L., Lu M. M., Seykora J., Millar S. E., Pear W. S., Parmacek M. S. (2006) Cancer Res. 66, 7438–7444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Deregowski V., Gazzerro E., Priest L., Rydziel S., Canalis E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6203–6210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Okubo T., Hogan B. L. (2004) J. Biol. 3, 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hirabayashi Y., Itoh Y., Tabata H., Nakajima K., Akiyama T., Masuyama N., Gotoh Y. (2004) Development 131, 2791–2801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Israsena N., Hu M., Fu W., Kan L., Kessler J. A. (2004) Dev. Biol. 268, 220–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chenn A., Walsh C. A. (2002) Science 297, 365–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyu J., Costantini F., Jho E. H., Joo C. K. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 13487–13495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maretto S., Cordenonsi M., Dupont S., Braghetta P., Broccoli V., Hassan A. B., Volpin D., Bressan G. M., Piccolo S. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 3299–3304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.