Abstract

The mechanisms by which cytosolic proteins reversibly bind the membrane and induce the curvature for membrane trafficking and remodeling remain elusive. The epsin N-terminal homology (ENTH) domain has potent vesicle tubulation activity despite a lack of intrinsic molecular curvature. EPR revealed that the N-terminal α-helix penetrates the phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate-containing membrane at a unique oblique angle and concomitantly interacts closely with helices from neighboring molecules in an antiparallel orientation. The quantitative fluorescence microscopy showed that the formation of highly ordered ENTH domain complexes beyond a critical size is essential for its vesicle tubulation activity. The mutations that interfere with the formation of large ENTH domain complexes abrogated the vesicle tubulation activity. Furthermore, the same mutations in the intact epsin 1 abolished its endocytic activity in mammalian cells. Collectively, these results show that the ENTH domain facilitates the cellular membrane budding and fission by a novel mechanism that is distinct from that proposed for BAR domains.

Introduction

Cell membranes undergo dynamic structural changes and remodeling during movement, division, and vesicle trafficking (1, 2). In particular, vesicle budding and fusion constantly take place in various cell membranes to maintain communication and transport between membrane-bound compartments (3). Dynamic membrane remodeling involves changes in local membrane curvature (or deformation) that are orchestrated by membrane lipids, integral membrane proteins, and cytoskeletal proteins (4, 5). Recently, several groups of cytosolic proteins that reversibly bind membranes and induce and/or detect different types of membrane curvatures during membrane remodeling have been identified. In particular, cytosolic proteins that are involved in different stages of clathrin-mediated endocytosis have received the most attention (6, 7), and many of them contain either an Ap180 N-terminal homology (ANTH)2/epsin N-terminal homology (ENTH) (8, 9) or a Bin-amphiphysin-Rvs (BAR) domain (9–12). Although ENTH (13) and BAR domains (14–17) have been reported to have in vitro vesicle-tubulating activities, the exact mechanisms by which these domains induce membrane deformation and larger scale membrane remodeling, especially under physiological conditions, are yet to be elucidated. For BAR domains, their unique intrinsic molecular curvatures have been postulated to be important for membrane deformation through a scaffolding mechanism (4). Also, recent studies have shown that F-BAR domains from FBP17 and CIP4 form highly ordered self-assembly in two-dimensional (18) and three-dimensional (19) crystals and that disruption of intermolecular interactions abrogates their membrane deformation activities. Despite remarkable success in structural characterization of various BAR and ENTH domains, questions still remain as to whether individual domains function by a universal mechanism or by different mechanisms, whether the intact proteins harboring these domains behave in the same manner as the isolated domains, especially under physiological conditions, and how and when these proteins contribute to endocytosis and other cellular vesicle budding processes.

The ENTH domain (∼140 amino acids) has a compact globular structure of eight α-helices and interhelical loops (20). This domain was first identified in epsin that binds the clathrin adaptor AP-2 (21). Subsequently, the ENTH domain was identified through homology searches in a number of proteins involved in the early stages of clathrin-mediated endocytosis. Structural studies have shown that these domains have similar structures despite low sequence similarity (13, 22, 23). The ENTH domain of AP180/CALM binds phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PtdIns(4,5)P2) via a cluster of surface basic residues (22). Surprisingly, the ENTH domain of epsin 1, which lacks this basic region, also binds PtdIns(4,5)P2 (23). The x-ray structure of the epsin 1-ENTH-inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (Ins(1,4,5)P3) complex revealed that Ins(1,4,5)P3 induces the formation of an N-terminal amphiphilic α-helix (H0) that constitutes the binding pocket for Ins(1,4,5)P3 (13). Also, in vitro studies (24, 25) of the epsin 1 ENTH domain indicated that hydrophobic residues on the same face of H0 penetrate the membrane in a PtdIns(4,5)P2-dependent manner, which is important for its vesicle tubulation activity. In contrast with the epsin 1 ENTH domain, the ENTH domain of CALM/AP180, which lacks the N-terminal amphiphilic α-helix, does not induce vesicle tubulation. It is thus generally believed that membrane penetration of H0 is essential for the generation of the positive membrane curvature and membrane deformation. For this reason, ENTH domains are often subdivided into ENTH (epsin-like) and ANTH (AP180/CALM-like) domains on the basis of the presence of the N-terminal amphiphilic α-helix (and vesicle-tubulating activity) (13). However, there are many proteins with membrane-penetrating amphiphilic α-helices that do not effectively induce membrane deformation, especially under physiological conditions. This raises a question as to how exactly some ENTH domains cause vesicle tubulation in vitro and facilitate vesicle budding during clathrin-mediated endocytosis. In this study, we have performed biophysical, structural, computational, and cell studies to elucidate the mechanism of vesicle tubulation by the epsin 1 ENTH domain. Results provide evidence for a novel mechanism in which the self-association of the ENTH domain into highly ordered aggregates on the membrane drives the membrane-remodeling activity of epsin 1.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

1-Palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine(POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (POPE), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine (POPS), and 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-lisamine rhodamine B sulfonyl (Rh-PE) were from Avanti Polar Lipids, and a 1,2-dipalmitoyl derivative of PtdIns(4,5)P2 was from Cayman Chemical. 1-Oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-Δ3-pyrroline-3-methyl)methanethiosulfonate (MTSL) was from Toronto Research Chemicals.

Protein Expression, Purification, and Labeling

The epsin 1 ENTH domain and mutants were expressed as N-terminal glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion proteins and purified using the GST-TagTM resin (Novagen) as described (24). The GST tag was cleaved by thrombin (Novagen) (24). Protein concentration was determined by the bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce). For EPR measurements, a single Cys at position 96 of epsin 1 ENTH WT was first mutated to Ala, and the C96A mutant was used as a template to introduce single or double Cys mutants. MTSL was then introduced on a single (or double) cysteine site of the ENTH domain WT or its mutants as a spin label. To the protein bound to the GST-TagTM resin, 10 mm dithiothreitol was added to the column to reduce all cysteines and then removed completely with an excess amount of 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 160 mm KCl. After 50 mm MTSL was added to the column, the mixture was incubated for 12 h at 4 °C with mild shaking, and free MTSL was removed with 200 ml of 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 160 mm KCl. The labeled protein was then cleaved from the resin by thrombin and purified as described (24). For fluorescent labeling at Cys96, an excess amount of Alexa Fluor 488 C5 maleimide (Invitrogen) was added to a column containing ENTH WT or a mutant, and the mixture was incubated for 16 h at 4 °C with mild shaking. The fluorescent labeling efficiency, calculated according to the manufacturer's protocol, was typically 60–80%.

EPR Measurements and Data Analysis

POPC, POPE (or POPS), and PtdIns(4,5)P2 in chloroform were mixed with a molar ratio of 77:20:3 and dried under vacuum overnight, and the mixture was resuspended in 25 mm Tris buffer, pH 7.4, with 100 mm KCl. Large unilamellar vesicles of 100-nm diameter were prepared from this suspension using an extruder equipped with a polycarbonate filter after >10 cycles of freezing (in the liquid nitrogen) and thawing. The final lipid concentration of vesicle solution was 50 mm. Spin-labeled ENTH wild type and mutants were gently mixed with vesicles at 4 °C for about 30 min. The lipid/protein molar ratio was kept at 200:1. The vesicle-bound proteins were then collected by centrifugation to reach the final protein concentrations of 250–300 μm. Continuous wave EPR spectra were collected using the Bruker ESP 300 spectrometer equipped with a loop-gap resonator (Medical Advances) and a low noise microwave amplifier (Miteq). The modulation amplitude was set at no greater than one-fourth of the line width. Room temperature (293 K) and low temperature (130 K) spectra were obtained. The data were collected in a first derivative mode for the room temperature measurement, whereas data were collected as the absorbance spectra for the low temperature measurement (26–28).

Giant Unilamellar Vesicle (GUV) Tubulation Assay

GUVs were prepared by the electroformation technique as described previously (29, 30). The lipid mixtures (POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2/Rh-PE = 46.5:30:20:3:05) were prepared in chloroform/methanol (3:1) at a total concentration of 0.5 mg/ml, and then the lipid solution was spread onto the indium tin oxide electrode surface, and the lipid was dried under vacuum to form a uniform lipid film. Vesicles were grown in a sucrose solution (typically 350 mm), whereas an electric field (3 V, 20 Hz frequency) was applied for 5 h at room temperature. The diameter of observed vesicles ranged from 5 to 30 μm. 1–2 μl of sucrose-loaded GUV solution was added into a well glued onto a coverslip that was placed on the stage of the Zeiss 200M microscope. The well contained 200 μl of 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, with 0.16 m KCl solution. After GUVs were sedimented in the bottom of the well, proteins were added gently, and the entire well was scanned with an automated x-y stage (2-min scan time) at 37 °C. Images were captured every 5 s with a CCD camera controlled with Metamorph software (Roper Scientific). Rh-PE was excited by an HBO 103 W/2 mercury lamp (Zeiss) with a Chroma D560/40 band pass filter, and the emission signal was monitored with a Chroma D630/60 band pass filter. The focal plane of the ×40 objective was continuously adjusted to obtain clear images of vesicles, and images were collected for up to 30 min. For each captured image, the numbers of total and tubulated GUVs (i.e. ones with buds or tubules) were counted and averaged over the full scan (i.e. 24 images). The percentage of tubulated vesicles was then plotted as a function of time. Alternately, the number of tubules per vesicles was calculated by dividing the total number of tubules and buds by the total number of vesicles and averaging these values over the full scan.

Number and Brightness Analysis of the Raster-scanned Fluorescence Microcopy Images

All microscopy measurements were carried out at 37 °C using a custom-built combination laser-scanning and multiphoton microscope that was described previously (31). Instrument control was accomplished with the help of ISS amplifiers, an ISS three-axis scanning card, and two ISS 200-kHz analog lifetime cards. All measurements were controlled and analyzed by the SimFCS. The average size of ENTH domain aggregates and the relative population of each aggregate as a function of time were determined by the number and brightness analysis as described (32) with a variation. To determine the aggregation state, a stack of 100 images of 64 × 64 pixels was collected at a pixel dwell time of 32 μs (see supplemental Fig. S1A). The brightness of each pixel was then determined by the first and second moment analysis of the fluorescence intensity fluctuation at each pixel (see supplemental Fig. S1B). The first and second moment moments of the distribution of photon counts (ki) correspond to the average (〈k〉) and the variance (σ2), respectively. Apparent brightness (B) and number (N) of particles for each pixel, which are defined as the ratio of variance to the average intensity and the ratio of total intensity to B, respectively, were then calculated from the equations, B = σ2/〈k〉 = ϵ + 1 and n = ϵn/(ϵ + 1), where ϵ and n indicate the true brightness and number of particles, respectively. N and B analysis of all pixels then produced two-dimensional maps of B and N (or intensity) (see supplemental Fig. S1C). From these maps, the number of pixels with a given B value was calculated at a given time. For instance, the ENTH domain pentamers have the B value of 1.25 (i.e. ϵ = 0.25) because the control experiment using the ENTH domain in solution showed that the monomer has a B value of 1.05 ± 0.03 (i.e. ϵ = 0.05). The time course of ENTH domain aggregates with different sizes was then determined for about 20 min, while the images of GUV were simultaneously recorded to detect vesicle deformation and tubulation.

Transferrin Receptor Endocytosis

NIH 3T3 and COS7 cells were seeded into 8-well plates and grown for 16 h at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air and 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fatal bovine serum (Invitrogen). Epsin 1 wild type and K23E/E42K (both C-terminal EGFP-tagged and prepared using the pEGFP-N1 vector (Clontech)) were transiently expressed by transfection with Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) in the serum-free DMEM. The medium was replaced with DMEM plus 10% serum after 4 h, and cells were incubated in the incubator for 16 h. Cells transiently expressing wild type and K23E/E42K epsin 1 were rinsed and incubated in serum-free DMEM for 2 h. The Texas Red-conjugated transferrin (Invitrogen; 1 μg/ml final concentration) mixed with the prewarmed serum-free medium was added to cells, and the cells were incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. Cells were rinsed with prewarmed phosphate-buffered saline twice and then fixed with the ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde solution. The cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline twice after 10-min fixation at room temperature. The effect of epsin 1 overexpression on transferrin internalization was monitored by confocal microscopy. For quantification of transferrin endocytosis, the puncta in each cell were counted. The cells with ≥15 transferrin puncta were counted as endocytosed cells, and the percentage of these cells was calculated for WT and mutant-transfected cells, respectively.

Molecular Modeling

A dimer model of the ENTH domain was constructed by molecular docking using the FTDOCK program (33). The total number of rotations performed was 9240 with a grid size set at 218 for Fourier transformation (i.e. a grid cube of 0.70177 Å). The top ranked results from the docking were filtered according to the H0 distance constraints suggested by the EPR analysis, and the best ranked structure was chosen. Side-chain placements were further optimized using a simple gradient descent algorithm. The interaction interface for the dimer was obtained by calculating the solvent-exposed area of the single domain and the complexed domain using the MSMS version 2.6.1 (34) algorithm with a probe size of 1.5 Å(surface of complex, 12,928 Å2; surface of single domain, 7190 Å2). Electrostatic calculation was performed using ABPS version 1.0 (35) for the native structure and mutants.

SPR Measurements

All equilibrium surface plasmon resonance (SPR) measurements were performed at 23 °C in 20 mm Tris, pH 7.4, containing 0.16 m KCl using a lipid-coated L1 chip in the BIACORE X system as described previously (36). Large unilamellar vesicles of POPC/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2 (77:20:3) and POPC were used as the active surface and the control surface, respectively. Sensorgrams were analyzed assuming a Langmuir-type binding between the protein (P) and protein binding sites (M) on vesicles (i.e. P + M ↔ PM) (37), and the Kd value was determined by a nonlinear least-squares analysis (37). Each data set was repeated three or more times to calculate average and S.D. values.

RESULTS

Vesicle Tubulation Activity of Epsin 1 ENTH Domain

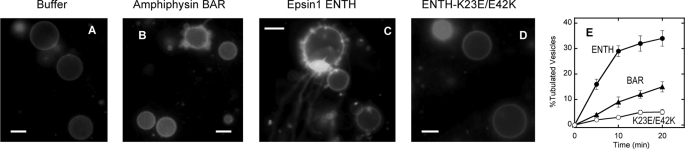

To date, vesicle tubulation activity of proteins has been measured primarily by electron microscopy (38, 39). Although the method provides high resolution images of the tubules generated by proteins, it does not allow continuous kinetic analysis that is necessary for quantitative evaluation and mechanistic investigation. Also, the method requires non-physiologically high concentrations of proteins (i.e. 5–10 μm). We therefore developed a fluorescence microscopy-based vesicle tubulation assay using sucrose-loaded GUV containing a fluorescence-labeled lipid that allows real-time kinetic analysis with submicromolar concentrations of proteins. GUV made of POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2/Rh-PE (46.5:30:20:3:0.5 molar ratio) were stable in the absence of proteins (Fig. 1A) but showed varying degrees of deformation and tubulation in the presence of different proteins. At a given time, 0.5 μm human epsin 1 ENTH domain clearly caused more vesicle deformation (Fig. 1C) than the same concentration of Drosophila amphiphysin BAR domain (Fig. 1B) and another BAR domain from human endophilin (data not shown). Also, the ENTH domain produced more developed tubules, whereas the BAR domains mostly generated small buds. When either the percentage of tubulated vesicles (Fig. 1E) or the number of tubules per vesicle (not shown) was plotted as a function of time, the ENTH domain had 2–3-fold higher activity than BAR domains. The vesicle tubulation activity gradually increased (in terms of both the percentage of tubulated vesicles and the number of tubules/vesicle) with increasing protein concentrations, and above 10 μm, the ENTH and the BAR domains showed comparable tubulation activity. The vesicle tubulation activity of the epsin 1 ENTH domain has been reported (13) and ascribed to its membrane-penetrating activity (24); however, it is somewhat surprising to find that the ENTH domain can have higher vesicle tubulation activity than the BAR domains despite the lack of the intrinsic molecular curvature that is thought to be important for the vesicle tubulation activity of BAR domains (1, 11, 14). This suggests that the epsin 1 ENTH domain has unique structural and physical properties that confer novel functionality to this small domain.

FIGURE 1.

GUV tubulation assay for epsin 1 ENTH and amphiphysin BAR domains. Shown are representative images of POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2/Rh-PE (46.5:30:20:3:0.5) GUV shown by Rh-PE fluorescence after treating for 10 min with the buffer solution (A), amphiphysin BAR (B), epsin 1 ENTH WT (C), and ENTH K23E/E42K mutant (D). E, the time course of the percentage of tubulated GUV caused by amphiphysin BAR (▴), epsin 1 ENTH WT (●), and ENTH K23E/E42K mutant (○). The average and S.D. values at each time point were determined from a minimum of three independent measurements. All measurements were performed at 37 °C in 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, with 0.16 m KCl solution. Protein concentration was 0.5 μm. White bars, 10 μm.

Membrane Interaction Mode of Epsin 1 ENTH Domain

Although it has been reported that H0 of epsin 1 ENTH domain penetrates the membrane in a PtdIns(4,5)P2-dependent manner (13, 24, 25), detailed structural information about the membrane-bound ENTH domains is not available. To understand the mechanism underlying the potent vesicle tubulation activity of the ENTH domain, we thus determined its membrane-docking topology by EPR analysis using a nitroxide scanning strategy. A single Cys at position 96 was first mutated to Ala to generate C96A that showed essentially the same binding activity for POPC/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2 (77:20:3) vesicles as wild type (WT) when assayed by SPR analysis (see Table 1). Using C96A as template, each residue in the H0 (residues 5–14) of the ENTH domain was mutated to Cys, and each Cys mutant was modified with a nitroxide spin label MTSL. Since H0 residues are involved in either PtdIns(4,5)P2 coordination (13) or membrane penetration (13, 24), some of these mutants and their spin-labeled forms showed significantly lower binding activity than WT (see Table 1). When the lipid-to-protein concentration ratio and the total lipid and protein concentration were kept high, however, these spin-labeled mutants could all bind the vesicles, thereby allowing us to collect the EPR signal of the membrane-bound protein.

TABLE 1.

Vesicle binding affinity of ENTH WT and mutants determined by SPR analysis

Vesicle binding affinity was measured using POPC/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2 (77:20:3) in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, containing 0.16 m KCl.

| Protein | Kd | Relative affinity |

|---|---|---|

| nm | % | |

| ENTH WT | 49 ± 8a | 100 |

| K23E/E42K | 75 ± 15a | 65 |

| C96A | 53 ± 7a | 2 |

| Q9C/C96A | 55 ± 9a | 89 |

| Q9C/C96A-MTSL | NDb | 95c |

| S5C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 92c |

| L6C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 50c |

| R7C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 15c |

| R8C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 20c |

| M10C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 55c |

| K11C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 25c |

| N12C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 90c |

| I13C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 50c |

| V14C/C96A-MTSL | ND | 53c |

| Q9C/K23E/E42K/C96A-MTSL | ND | 70c |

| WT-Alexa Fluor 488 | ND | 99c |

| K23E/E42K-Alexa Fluor 488 | ND | 65c |

a Determined by the curve fitting of binding isotherms derived from equilibrium SPR sensorgrams.

b ND, not determined.

c Estimated from the relative resonance unit when the same concentrations of WT and mutants were injected onto the vesicle surface (at least two different concentrations were used for comparison).

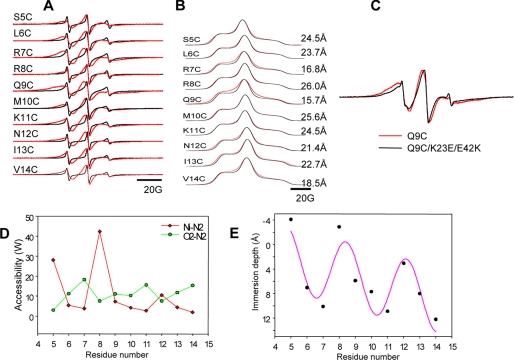

We first measured the structural transition of H0 in the presence of POPC/POPS (80:20) vesicles and POPC/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2 (77:20:3) vesicles by monitoring the EPR line shape changes. As shown in Fig. 2A and in agreement with a previous report (25), the EPR spectra of the H0 region were significantly broadened in the presence of PtdIns(4,5)P2 in the vesicle, indicating the necessity of PtdIns(4,5)P2 for membrane binding. We then determined the membrane-bound topology of H0 by the EPR power saturation method (40), which measures the accessibility (W) of the spin label to a water-soluble paramagnetic reagent, such as Ni(II) ethylenediamine-N,N′-diacetate (NiEDDA) or to a nonpolar paramagnetic reagent, such as O2 (27, 28). For individual mutants, three power saturation curves were obtained after equilibration with N2, with air (N2 + O2), and with N2 in the presence of 200 mm NiEDDA. From saturation curves, the accessibility of the spin labels to O2 (WO2) and NiEDDA (WNiEDDA), respectively, was determined (Fig. 2D), and then the immersion depth of the MTSL spin label substituted in each position of the H0 was calculated based on the reference curves (Fig. 2E) (40). A modified sine function that was developed to fit the immersion depth data to a model α-helix successfully fit our data, indicating that residues 5–14 in the H0 form an α-helix in the membrane, similar to the previous findings (27). The immersion depth profile of H0 shows that hydrophobic side chains, Leu6, Met10, Ile13, and Val14, are inserted into the membrane, reaching up to 13 Åfrom the phosphate group. This degree of membrane penetration depth is comparable with that reported for other amphiphilic α-helices determined by EPR analysis. However, the curve fitting also suggests that H0 penetrates the membrane in a unique slanted orientation, similar to the fusion peptide of influenza hemagglutinin (41), with the helical axis forming an about 11° angle against the membrane normal (Fig. 3A). This in turn suggests the novel oblique angle membrane penetration of H0 may play a role in potent membrane-deforming activity of the ENTH domain. The analysis also indicated that Lys7 and Lys11 are inserted into the membrane. However, this is presumably due to the substitution of lysines with less polar MTSL-labeled cysteines. In the native structure, these lysine side chains are expected to be tucked in so that their ϵ-amino groups may interact with polar headgroups.

FIGURE 2.

EPR spectra of epsin 1 ENTH domain. A, room temperature EPR spectra for the N terminus of the epsin 1 ENTH domain (C96A). The black lines show the EPR spectra in the presence of POPC/POPS (80:20) vesicles, whereas the red lines indicate the EPR spectra with POPC/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2 (77:20:3) vesicles. B, low temperature EPR spectra and distance measurements by Fourier deconvolution analysis. Low temperature absorbance (integrated) spectra for spin-labeled mutants (red lines) are compared with a reference spectrum (black lines). The exact spin-spin distance for each mutant was measured by Fourier deconvolution analysis and shown at the end of each line. C, comparisons of room temperature EPR spectra of Q9C(/C96A) and Q9C/K23E/E42K(/C96A). The red line is the spectrum of Q9C(/C96A), which shows the spin-spin interaction even at room temperature. The black line represents Q9C/K23E/E42K(/C96A). D, the accessibility parameters WO2 (green filled circles) and WNiEDDA (red diamonds) plotted as functions of the residue number of the N terminus of the ENTH domain. E, the immersion depth of each residue, defined as a linear term of the logarithm of the ratio of accessibility to NIEDDA to accessibility to O2, is plotted as a function of the residue number. The pink solid line is the fit with a modified sine function. The linear term is added to the sine function to take into account the tilt angle as 23°. All proteins were labeled with MTSL. The lipid/protein ratio was 200:1 for all measurements. All spectra were recorded at 120-gauss magnetic field.

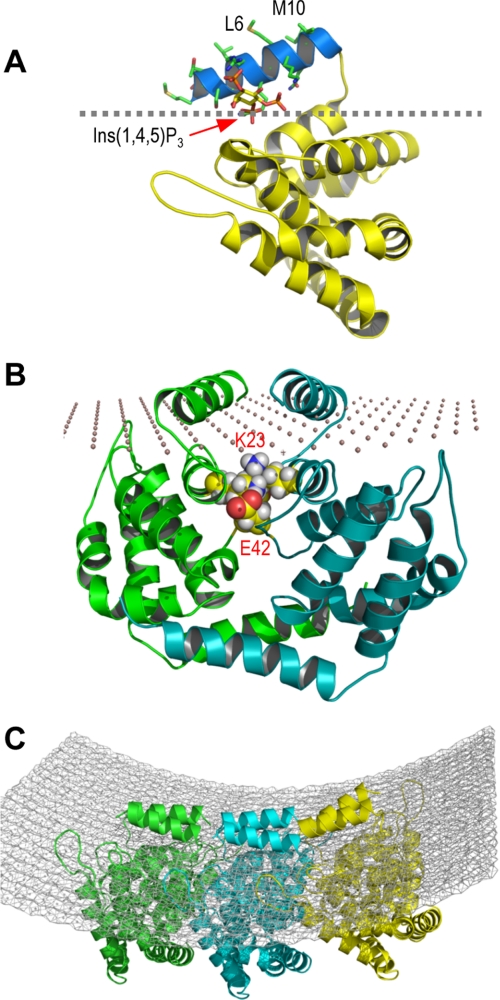

FIGURE 3.

Modes of membrane binding and self-association of epsin 1 ENTH domain. A, a proposed membrane binding topology of the epsin 1 ENTH domain based on the immersion depth of N-terminal residues shown in Fig. 2E. H0 is colored blue, and hydrophobic side chains are labeled. The structure of the ENTH domain with the bound Ins(1,4,5)P3 is from Ford et al. (13). B, an energy-minimized model structure of the docked ENTH domain dimer built on the basis of EPR distance restraints. The side chains of Lys23 and Glu42 are shown in a space-filling representation, and these residues in one monomeric unit (green) are labeled. The membrane surface is illustrated with simple dots. C, a hypothetical model of ENTH domain hexamer bound to the membrane. The model was built by molecular docking of the dimer models shown in Fig. 3B and energy minimization. Notice that this model hexamer structure arranges six H0 units in such a way that they interact more energetically favorably with a curved membrane than with a flat membrane.

Interestingly, a significant degree of spin-spin interaction was observed with some single-site labeled mutants, including R7C and Q9C, which was evident in the EPR spectra at low temperature (130 K; Fig. 2B). In particular, the interspin distance was within 17 Åfor the spin labels attached to two H0 residues, R7C and Q9C. These distance measurements by low temperature EPR (26) suggest that neighboring H0 units interact with one another in an antiparallel manner, which in turn suggests the well ordered clustering of membrane-bound epsin 1 ENTH domains.

To better understand the structural basis and the functional consequences of the aggregation of membrane-bound epsin 1 ENTH domains, we built an energy-minimized model of the ENTH dimer as a minimal unit of self-associated ENTH domains on the basis of our EPR data (Fig. 3B). The model suggests that the two ENTH domains interact with a reasonably large interface of 726 A2, and several residues, including Arg7, Gln9, and Val14 in H0, Lys23, and Glu42, are involved in intermolecular interactions. To generate mutants that disrupt ENTH aggregation without decreasing its membrane affinity, we focused on non-H0 residues, Lys23 and Glu42, and prepared several mutants, including K23A, K23E, E42A, and E42K; unfortunately, however, their low bacterial expression levels hampered further characterization. Interestingly, we found that a double charge reversal mutant, K23E/E42K, had drastically reduced vesicle tubulation activity (see Fig. 1, D and E) despite having the same net charge as the WT and only modestly reduced membrane affinity (Table 1). Electrostatic calculation indicates that K23E/E42K has lower interaction energy than WT by about 2.6 kcal/mol due to restricted placement of mutated side chains, which may cause K23E/E42K to self-associate to a significantly lower degree than WT. We thus used this mutant to check the validity of our structural model of self-association for the membrane-bound ENTH domain.

The Q9C/K23E/E42K/C96A mutant had about 75% of the affinity of Q9C/C96A for POPC/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2 (70:20:3) vesicles when assayed by SPR analysis (see Table 1). As a result, a significant and comparable portion of these proteins were membrane-associated in the presence of excess lipids and gave EPR signals after pelleting with the vesicles. As shown in Fig. 2C, the K23E/E42K mutation greatly reduced the spin-spin coupling of the spin-labeled Q9C, suggesting that Lys23 and Glu42 are involved in intermolecular interactions, and the aggregation of the ENTH domain on the vesicle surface is directly correlated with its vesicle-deforming activity.

Quantification of Protein Self-association by Number and Brightness Analysis

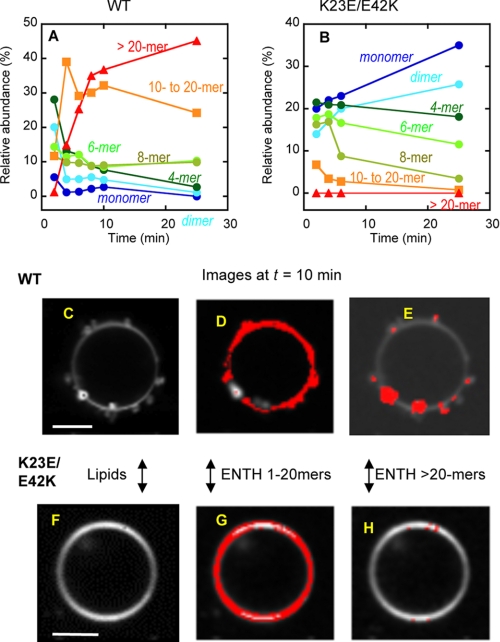

To further investigate the extent of the self-association of the epsin 1 ENTH domain on the membrane, we performed the number and brightness analysis on the raster-scanned images that has been successfully employed in quantification of particle and protein aggregation (32). For these studies, the ENTH domain was labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 C5 maleimide on a single Cys at position 96 that is remote from H0. Alexa Fluor 488-labeled WT has essentially the same membrane affinity as WT when measured by SPR analysis (see Table 1). The fluorescence-labeled ENTH was used with POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2/Rh-PE (46.5:30:20:3:0.5) GUV. A main advantage of our orthogonal fluorescence labeling approach is that it allows direct real-time spatiotemporal correlation between protein aggregation and vesicle deformation because both processes can be simultaneously monitored. For the number and brightness analysis, we mainly selected modestly deformed GUVs among various types of deformed vesicles (see Fig. 4C), because further deformed vesicles with fully developed tubules were too unstable and wobbly to perform time-dependent quantitative imaging.

FIGURE 4.

Number and brightness analysis of raster-scanned images of GUV tubulation by ENTH domain. A, the time course of the relative abundance of different aggregates for epsin 1 ENTH WT. B, the time course of the relative abundance of different aggregates for epsin ENTH K23E/E42K mutant. C, a representative image of POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2/Rh-PE GUV shown by Rh-PE fluorescence after a 10-min treatment with epsin 1 ENTH WT. D, distribution of ENTH WT aggregates (monomer to 20-mer) was superimposed onto the image of GUV. E, distribution of ENTH WT aggregates (>20-mer) was superimposed onto the image of GUV. F, a representative image of POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2/Rh-PE GUV after a 10-min treatment with epsin 1 ENTH K23E/E42K. G, distribution of ENTH K23E/E42K (monomer to 20-mer) was superimposed onto the image of GUV. H, distribution of ENTH K23E/E42K aggregates (>20-mer) was superimposed onto the image of GUV. All measurements were performed at 37 °C using POPC/POPE/POPS/PtdIns(4,5)P2/Rh-PE (46.5:30:20:3:0.5) GUV in 20 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.4, with 0.16 m KCl solution. Protein concentration was 0.5 μm. White bars, 10 μm.

Raster-scanned images (see supplemental Fig. S1A) of the fluorescence-labeled ENTH domain interacting with the GUV was subjected to the first and second moment analysis to yield apparent brightness (B) and number (N) (or intensity) (see supplemental Fig. S1, B and C). The true brightness (ϵ = B − 1) of each protein species was then determined from B. The epsin 1 ENTH domain is known to exist as monomer in solution (13, 23), which was confirmed by our gel filtration chromatography experiment; it remained as a monomer with a protein concentration up to 10 μm (data not shown). We therefore determined the B value (1.05 ± 0.03; i.e. ϵ = 0.05) for the monomeric ENTH domain by analyzing the free ENTH domain in the absence of GUV. Using this ϵ value, we then assigned the average aggregation state of the protein in individual pixels from their ϵ values (e.g. for dimers, ϵ = 0.1 (or B = 1.1); for trimers, ϵ = 0.15 (or B = 1.15); etc.). It should be noted that a particular aggregate (e.g. pentamer) determined by our analysis represents a tightly associated molecular complex that diffuses as a single unit, not a transiently and loosely bound species formed by protein crowding. The pixels corresponding to each aggregate at a given time were counted, and the relative population of each species was plotted as a function of time (Fig. 4A).

When the ENTH domain was added to the GUV, it rapidly bound the GUV, as indicated by the strong Alexa Fluor 488 fluorescence intensity at the GUV surface (data not shown). At the earliest time (i.e. 2 min) that allowed statistically robust number and brightness analysis, the ENTH domain already existed as a highly heterogeneous mixture of protein aggregates with smaller aggregates (i.e. dimer to octamer) forming the majority, suggesting that the domain spontaneously starts to aggregate on the vesicle surface. After 4 min, larger aggregates (i.e. 10-mer to >100-mer) began to predominate, and the relative abundance of those larger than 20-mer reached more than 40% after 10 min (Fig. 4A). Importantly, the formation of these large aggregates synchronized with the generation of tubules from vesicles. A more detailed time course map for 10–30-mer (see supplemental Fig. S2) shows that the accumulation of 20–22-mer is best synchronized with vesicle tubulation, further corroborating the notion that the formation of ENTH domain clusters larger than a 20-mer is essential for vesicle tubulation. The vesicles visualized by monitoring Rh-PE fluorescence started to show deformation after 3–5 min and contained extensive short tubules after 10 min (Fig. 4C). When the images of GUV (see white spheres in Fig. 4, D and E) were superimposed with the distribution of different aggregates of the ENTH domain (see red images in Fig. 4, D and E), those aggregates that are larger than a 20-mer were only concentrated on tubules, whereas smaller aggregates were rather evenly distributed over the vesicular surfaces. Through all phases of vesicle interactions, the relative population of a monomeric species of the ENTH domain remained minor to negligible. Essentially the same trend was observed with >20 GUVs that were tubulated by the ENTH WT.

In contrast to the WT ENTH domain, the K23E/E42K mutant with abrogated vesicle tubulation activity did not form large aggregates (Fig. 4H). The monomer and smaller aggregates predominate throughout the entire time course (Fig. 4B). Also, K23E/E42K caused little to no damage to vesicles (Fig. 4F), and its monomer and smaller aggregates are evenly distributed over the vesicular surfaces (Fig. 4G). The same trend was seen even with 5 μm K23E/E42K, showing that the ENTH domain aggregation is not a nonspecific clustering driven by protein crowding. Furthermore, when K23E/E42K and WT were mixed at a 1:1 ratio, WT showed little to no tendency to deform vesicles and form large self-aggregates, indicating that the mutant inhibits the aggregation of WT presumably by interfering with its optimal intermolecular interactions. This in turn underscores the specific nature of the ENTH domain aggregation. Together, these results demonstrate the direct spatial and temporal correlation between the higher-order self-association of the ENTH domain and its vesicle tubulation activity.

Physiological Significance of ENTH Domain Aggregation

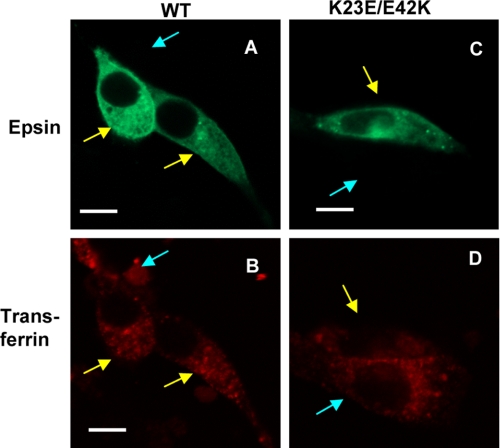

Epsin 1 has been proposed to serve as an endocytic adaptor. It has been reported that epsin 1 mutants that cannot effectively bind PtdIns(4,5)P2 strongly inhibit the clathrin-mediated endocytosis of epidermal growth factor and transferrin receptors when overexpressed in COS7 cells, whereas WT does not influence the endocytosis of these receptors (13, 23). To assess the importance of the ENTH domain aggregation in the physiological function of epsin 1, we measured the effects of overexpressing full-length epsin 1 WT and K23E/E43K in NIH 3T3 cells. As reported previously (13, 23), epsin 1 WT with a C-terminal EGFP tag showed largely cytosolic distribution with some localization in the plasma membrane (Fig. 5A), and transferrin receptors visualized by Texas Red-labeled transferrin were seen as puncta in the cytosol and in the perinuclear region in all cells, regardless of overexpression of epsin 1 WT (Fig. 5B). Thus, exogenous epsin 1 had only a minor effect on the transferrin receptor endocytosis, presumably due to the presence of endogenous epsin 1. In contrast, overexpression of K23E/E43K, which showed similar subcellular distribution to the WT (Fig. 5C), strongly inhibited transferrin receptor endocytosis (Fig. 5D, compare the receptor distribution in K23E/E43K-expressing (yellow arrow) and non-expressing (cyan arrow) cells). Among >100 cells examined, the transferrin endocytosis was observed in 86% of cells expressing WT but only 25% of cells expressing K23E/E43K. Similar results were seen in COS7 cells. It is therefore clear that the full-length K23E/E43K mutant inhibits the endocytic function of endogenous epsin 1. In conjunction with our in vitro results indicating that the K23E/E43K mutant of the ENTH domain inhibits the self-association of the WT ENTH domain, these results support the notion that the intact epsin 1 also aggregates through the self-association of its N-terminal ENTH domain on the plasma membrane and that this aggregation is important for the endocytic function of epsin 1.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of epsin 1 and its mutant on the internalization of transferrin. Shown is cellular distribution of transiently transfected epsin 1-EGFP (A) and Texas Red-labeled transferrin (B) in NIH 3T3 cells 10 min after treatment with 1 μg/ml Texas Red-transferrin. Also shown is cellular distribution of transiently transfected epsin 1-K23E/E42K-EGFP (C) and Texas Red-transferrin (D) in NIH 3T3 cells 10 min after the transferrin treatment. Notice that the transferrin internalization was observed in both epsin 1-overexpressing (yellow arrows) and non-expressing (cyan arrow) cells in B but primarily in non-expressing cells in D. White bars, 10 μm.

DISCUSSION

The present study provides new evidence that the epsin 1 ENTH domain induces membrane deformation through a unique mechanism involving protein self-association. It also indicates that the aggregation of the ENTH domain also occurs in the context of the full-length protein and has significant functional consequences under physiological conditions. It has been well established that PtdIns(4,5)P2 induces the formation of the amphiphilic H0 helix structure of the epsin 1 ENTH domain (13), which then causes hydrophobic residues on H0 to penetrate the membrane (24, 25). It is generally thought that the insertion of H0 to one leaflet of the lipid bilayer causes a discrepancy in bilayer surface area and consequently the positive curvature and membrane deformation (13). Membrane penetration by an amphiphilic α-helix is also postulated to be important for the membrane-deforming activity of N-BAR domains, including those from amphiphysin (14, 42) and endophilin (43, 44). However, it does not fully explain why the epsin 1 ENTH domain has such potent membrane-deforming activity despite not having intrinsic molecular curvature and why many other proteins with amphiphilic α-helices or hydrophobic loops show a much lower tendency to deform the lipid bilayer. Our EPR and fluorescence microscopy results strongly suggest that the potent membrane-deforming activity of the epsin 1 ENTH domain mainly derives from the unique oblique angle membrane penetration of its H0 and its self-association into highly ordered large protein complexes, which is distinct from simple physical crowding, on the membrane surface. Hydrophobic residues, Leu6, Met10, Ile13, and Val14, on one face of the PtdIns(4,5)P2-induced H0 penetrate into the hydrophobic region of the lipid bilayer in a slanted orientation with the helix axis forming an ∼11° degree angle against the membrane normal. In this orientation, Arg7, Gln9, and Val14 in the H0 serve as an intermolecular interaction surface for the epsin 1 ENTH domain. Thus, the formation of the amphiphilic H0 not only facilitates the membrane penetration of the ENTH domain but also promotes favorable intermolecular interactions, as seen in our dimer model illustrated in Fig. 3B. In solution where the N-terminal region was reported to be unstructured (13, 23), the epsin 1 ENTH domain does not show any tendency to aggregate even at micromolar concentrations.

Our newly developed GUV tubulation assay and number and brightness analysis provide unprecedented mechanistic details about the protein-induced vesicle deformation. The vesicle deformation and tubulation is temporally and spatially correlated with the formation of large ENTH domain complexes on the vesicle surface. The time course of the formation of large protein aggregates is well synchronized with the vesicle tubulation, and these protein complexes are predominantly localized at protruding buds and tubules. The brightness analysis indicates that the ENTH domain spontaneously forms a highly heterogeneous mixture of protein aggregates upon binding to PtdIns(4,5)P2-containing GUV. The mixture is mainly composed of smaller complexes initially but gradually dominated by much larger protein complexes. These results suggest that there is a critical size of the protein complex required for effective vesicle tubulation, the formation of which accounts for the time course of vesicle tubulation. Above the critical size, the mechanical force exerted by concerted penetration of multiple H0 units would seem sufficient to cause the positive curvature formation and membrane deformation. Undoubtedly, further studies are required to determine how the ENTH domain forms large protein complexes and how they drive the membrane deformation. Intriguingly, our preliminary molecular dynamics simulation implies that the ENTH domain can form well ordered complexes using the dimer in Fig. 3B as a repeating unit (see Fig. 3C) and that these complexes interact more energetically favorably with a curved membrane than with a flat membrane. This is in contrast to the monomer and the dimer that interact favorably with the flat membrane. It is also consistent with our finding that large ENTH complexes are mainly found in the highly curved buds and tubules (see Fig. 4E). Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that the formation of large well ordered complexes beyond the critical size induces the local membrane curvature, thereby driving membrane deformation and tubulation. Judging from the inability of K23E/E42K to induce vesicle tubulation despite its tendency to form smaller aggregates, the penetration of multiple H0 units from highly ordered protein complexes must be synergistic and much more effective than that of H0 units from scattered patches of smaller ENTH domain aggregates or monomeric ENTH domains. Although it is difficult to determine the critical cluster size accurately due to the highly dynamic nature of protein self-association, our detailed number and brightness analysis (see supplemental Fig. S2) suggests that it is around 20–22-mer under our experimental conditions. Obviously, the value would vary significantly, depending on the physiochemical properties of vesicles and other factors, including the presence of other proteins.

Previous reports have suggested that the N-terminal ENTH domain is functionally responsible for the intact epsin 1. For instance, genetic studies in yeast and Dictyostelium discoideum showed that the N-terminal ENTH domains of Ent1p (45) and epnA (46), respectively, which are epsin 1 orthologs, are sufficient for the cellular function of these epsins, although the C-terminal regions are also necessary for protein-protein interactions and localization. Our results showing that the K23E/E42K mutation that disrupts the self-association of the ENTH domain abrogates the cellular endocytic function of the full-length epsin 1 strongly suggest that the ENTH domain mainly accounts for the physiological activity of epsin 1 and that the self-association of the membrane-bound ENTH domain is essential for the physiological activity of epsin 1. It should be noted that such a functional correlation has not been reported between an isolated BAR domain and its intact protein under physiological conditions. An attempt to directly measure the self-association of the full-length epsin 1 in vitro was unsuccessful due to the difficulty encountered in the expression and purification of epsin 1.

Collectively, the present results provide new mechanistic insight into how the small ENTH domain exerts potent vesicle tubulation activity. Our study also demonstrates the differences in membrane-deforming activity and mechanism between ENTH and BAR domains. This in turn provides additional insight into different physiological functions of these proteins. Epsin family members, epsin 1 in particular, have been implicated in inducing membrane curvature at the onset of endocytosis, on the basis of biophysical and cellular studies using WT and mutants of isolated ENTH domains and intact epsin proteins (13, 23). The epsin 1 ENTH domain has potent activity to induce positive membrane curvature from lamellar lipid bilayers; thus, it is well suited for its putative role. Clathrin, other endocytic adaptor proteins, and accessory proteins will then take over the process of vesicle budding and fission. BAR domains have lower activity than the ENTH domain to form tubules from lamellar lipid bilayers, but they can also stabilize the tubules using their intrinsic molecular curvature. Thus, they may be better suited for a later stage of clathrin-mediated endocytosis (e.g. extension and stabilization of narrow necks of budding vesicles).

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM68849 (to W. C.), GM51290 (to Y.-K. S.), and PHS 5 P41-RR03155 (to E. G.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1 and S2.

- ANTH

- Ap180 N-terminal homology

- BAR

- Bin-amphiphysin-Rvs

- DMEM

- Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium

- EGFP

- enhanced green fluorescence protein

- ENTH

- epsin N-terminal homology

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- GUV

- giant unilamellar vesicles

- MTSL

- 1-oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-Δ3-pyrroline-3-methyl)methanethiosulfonate

- POPC

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- POPE

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- POPS

- 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoserine

- PtdIns(4,5)P2

- phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

- Rh-PE

- 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-lisamine rhodamine B sulfonyl

- SPR

- surface plasmon resonance

- WT

- wild type

- H0

- amphiphilic α-helix

- Ins(1,4,5)P3

- inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate

- NiEDDA

- Ni(II) ethylenediamine-N,N′-diacetate.

REFERENCES

- 1.McMahon H. T., Gallop J. L. (2005) Nature 438, 590–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McNiven M. A., Thompson H. M. (2006) Science 313, 1591–1594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chernomordik L. V., Kozlov M. M. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 175–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farsad K., De Camilli P. (2003) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 372–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerberg J., Kozlov M. M. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 9–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins M. K., McMahon H. T. (2002) Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 257–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Le Roy C., Wrana J. L. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 112–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho W., Stahelin R. V. (2005) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 34, 119–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Itoh T., De Camilli P. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1761, 897–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Habermann B. (2004) EMBO Rep. 5, 250–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson J. C., Legg J. A., Machesky L. M. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16, 493–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heath R. J., Insall R. H. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 1951–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ford M. G., Mills I. G., Peter B. J., Vallis Y., Praefcke G. J., Evans P. R., McMahon H. T. (2002) Nature 419, 361–366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peter B. J., Kent H. M., Mills I. G., Vallis Y., Butler P. J., Evans P. R., McMahon H. T. (2004) Science 303, 495–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Itoh T., Erdmann K. S., Roux A., Habermann B., Werner H., De Camilli P. (2005) Dev. Cell 9, 791–804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsujita K., Suetsugu S., Sasaki N., Furutani M., Oikawa T., Takenawa T. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 172, 269–279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattila P. K., Pykäläinen A., Saarikangas J., Paavilainen V. O., Vihinen H., Jokitalo E., Lappalainen P. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 176, 953–964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frost A., Perera R., Roux A., Spasov K., Destaing O., Egelman E. H., De Camilli P., Unger V. M. (2008) Cell 132, 807–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimada A., Niwa H., Tsujita K., Suetsugu S., Nitta K., Hanawa-Suetsugu K., Akasaka R., Nishino Y., Toyama M., Chen L., Liu Z. J., Wang B. C., Yamamoto M., Terada T., Miyazawa A., Tanaka A., Sugano S., Shirouzu M., Nagayama K., Takenawa T., Yokoyama S. (2007) Cell 129, 761–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Camilli P., Chen H., Hyman J., Panepucci E., Bateman A., Brunger A. T. (2002) FEBS Lett. 513, 11–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kay B. K., Yamabhai M., Wendland B., Emr S. D. (1999) Protein Sci. 8, 435–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ford M. G., Pearse B. M., Higgins M. K., Vallis Y., Owen D. J., Gibson A., Hopkins C. R., Evans P. R., McMahon H. T. (2001) Science 291, 1051–1055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoh T., Koshiba S., Kigawa T., Kikuchi A., Yokoyama S., Takenawa T. (2001) Science 291, 1047–1051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stahelin R. V., Long F., Peter B. J., Murray D., De Camilli P., McMahon H. T., Cho W. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 28993–28999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kweon D. H., Shin Y. K., Shin J. Y., Lee J. H., Lee J. B., Seo J. H., Kim Y. S. (2006) Mol. Cells 21, 428–435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kweon D. H., Chen Y., Zhang F., Poirier M., Kim C. S., Shin Y. K. (2002) Biochemistry 41, 5449–5452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kweon D. H., Kim C. S., Shin Y. K. (2003) Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 440–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y., Xu Y., Zhang F., Shin Y. K. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 681–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bagatolli L. A., Gratton E. (1999) Biophys. J. 77, 2090–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gokhale N. A., Abraham A., Digman M. A., Gratton E., Cho W. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 42831–42840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stahelin R. V., Digman M. A., Medkova M., Ananthanarayanan B., Rafter J. D., Melowic H. R., Cho W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 29501–29512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Digman M. A., Dalal R., Horwitz A. F., Gratton E. (2008) Biophys. J. 94, 2320–2332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katchalski-Katzir E., Shariv I., Eisenstein M., Friesem A. A., Aflalo C., Vakser I. A. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 2195–2199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanner M. F., Olson A. J., Spehner J. C. (1996) Biopolymers 38, 305–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baker N. A., Sept D., Joseph S., Holst M. J., McCammon J. A. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 10037–10041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stahelin R. V., Cho W. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 4672–4678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho W., Bittova L., Stahelin R. V. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 296, 153–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Takei K., Slepnev V. I., Haucke V., De Camilli P. (1999) Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 33–39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Farsad K., Ringstad N., Takei K., Floyd S. R., Rose K., De Camilli P. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 155, 193–200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Altenbach C., Greenhalgh D. A., Khorana H. G., Hubbell W. L. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 91, 1667–1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macosko J. C., Kim C. H., Shin Y. K. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 267, 1139–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Blood P. D., Swenson R. D., Voth G. A. (2008) Biophys. J. 95, 1866–1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Masuda M., Takeda S., Sone M., Ohki T., Mori H., Kamioka Y., Mochizuki N. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 2889–2897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gallop J. L., Jao C. C., Kent H. M., Butler P. J., Evans P. R., Langen R., McMahon H. T. (2006) EMBO J. 25, 2898–2910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wendland B., Steece K. E., Emr S. D. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 4383–4393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brady R. J., Wen Y., O'Halloran T. J. (2008) J. Cell Sci. 121, 3433–3444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.