Abstract

EphA and EphB receptors preferentially bind ephrin-A and ephrin-B ligands, respectively, but EphA4 is exceptional for its ability to bind all ephrins. Here, we report the crystal structure of the EphA4 ligand-binding domain in complex with ephrin-B2, which represents the first structure of an EphA-ephrin-B interclass complex. A loose fit of the ephrin-B2 G-H loop in the EphA4 ligand-binding channel is consistent with a relatively weak binding affinity. Additional surface contacts also exist between EphA4 residues Gln12 and Glu14 and ephrin-B2. Mutation of Gln12 and Glu14 does not cause significant structural changes in EphA4 or changes in its affinity for ephrin-A ligands. However, the EphA4 mutant has ∼10-fold reduced affinity for ephrin-B ligands, indicating that the surface contacts are critical for interclass but not intraclass ephrin binding. Thus, EphA4 uses different strategies to bind ephrin-A or ephrin-B ligands and achieve binding promiscuity. NMR characterization also suggests that the contacts of Gln12 and Glu14 with ephrin-B2 induce dynamic changes throughout the whole EphA4 ligand-binding domain. Our findings shed light on the distinctive features that enable the remarkable ligand binding promiscuity of EphA4 and suggest that diverse strategies are needed to effectively disrupt different Eph-ephrin complexes.

Introduction

The Eph receptors represent the largest family of tyrosine kinases, with 16 members divided into two classes, EphA and EphB. This subdivision is based on sequence conservation and binding preferences for their ligands, the ephrins, which are also divided into A and B classes. There are 10 EphA and 6 EphB receptors in mammals and chick, which can bind to six glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored ephrin-A ligands or three transmembrane ephrin-B ligands to mediate an extremely wide spectrum of biological responses through signals that are generated by both receptor and ligand activation (1, 2).

All of the Eph receptors share the same modular structure, which comprises a juxtamembrane region, a tyrosine kinase domain, a C-terminal sterile α-motif domain, and a PDZ-binding motif in the intracellular region. In the extracellular portion, there are an N-terminal ligand-binding domain, a cysteine-rich region, and two fibronectin type III repeats. The ephrin-binding domain is responsible for ligand recognition and is composed of 11 antiparallel β-strands organized in a jellyroll β-sandwich architecture, which is conserved among EphA and EphB receptors (3–8). The ectodomain of the ephrins is also conserved and consists of an eight-stranded β-barrel with a Greek key topology, including several large and highly conserved functional loops, such as the G-H and C-D loops (4, 5, 8, 9), which are very flexible in solution (10).

The formation of a complex between an Eph receptor and an ephrin is centered around the insertion of the solvent-exposed ephrin G-H loop into the Eph receptor hydrophobic channel formed by the convex sheet of four β-strands together with the D-E, J-K, and G-H loops. These interactions are mostly hydrophobic and, together with an adjacent mostly polar surface region, form the high affinity interface of Eph receptor-ephrin complexes, which is involved in receptor-ephrin dimerization (4–6, 8). Other interfaces contribute to Eph-ephrin binding, including (i) additional residues on both the receptor and ephrin surfaces; (ii) a low affinity interface also involving the Eph receptor ligand-binding domain, which was identified in the EphB2-ephrin-B2 complex and appears to mediate the association of two receptor-ephrin dimers (tetramerization) (4), and (iii) an interface involving the cysteine-rich region adjacent to the Eph receptor ligand-binding domain, which was identified by mutagenesis in the EphA3-ephrin-A5 complex but has not been structurally characterized and which might be implicated in higher order clustering (11).

Although Eph receptors interact promiscuously with ephrins of the same class, they rarely interact with ephrins of the other class. A variety of factors appear to contribute to class specificity. B class Eph-ephrin interactions require considerable structural rearrangements of both the receptor and the ephrin, whereas EphA receptors and ephrin-A ligands appear to undergo smaller rearrangements when forming a complex (8). Differences in critical residues located in the interacting regions and sequence differences in the class specificity H-I loop of the Eph receptors also seem to play a role in class specificity (3–8). However, examples of interclass binding also exist: EphB2 can bind ephrin-A5, and EphA4 can bind all three ephrin-B ligands (12).

The structure of the EphB2 ephrin-binding domain in complex with ephrin-A5 has been determined (5) and shows that the two proteins interact only through the high affinity interface, which is greatly reduced compared with intraclass complexes, resulting in a lower binding affinity. EphA4 binding to ephrin-B ligands is also weaker than to ephrin-A ligands. However, the physiological relevance of EphA4-ephrin-B interclass interactions has been demonstrated in many biological systems. For example, EphA4 interaction with ephrin-B1 stabilizes blood clot formation (13), whereas EphA4 interaction with ephrin-B2 and/or ephrin-B3 regulates cell sorting in the rhombomeres and branchial arches of the developing hindbrain (14, 15), somite morphogenesis (16), axon guidance and circuit formation in the developing spinal cord (17–20), and inhibition of axon outgrowth by myelin (21).

The distinctive ability of EphA4 to bind both ephrin-A and ephrin-B ligands makes it an attractive model to understand the structural principles underlying the selectivity versus promiscuity of Eph receptor-ephrin interactions, but no structural information has been available for EphA4-ephrin complexes. In this study, we report the crystal structure of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex and identify a polar contact region, structurally separated from the ephrin-binding channel, as critical for EphA4-ephrin-B2 binding. We also characterized the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex in solution by NMR spectroscopy, which represents the first NMR visualization of an Eph-ephrin complex. Interestingly, our results show that EphA4 uses different strategies for binding ephrin-A versus ephrin-B ligands, thus achieving remarkable promiscuity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cloning, Expression, and Purification of Recombinant Proteins in Escherichia coli

The wild-type EphA4 ligand-binding domain (residues 29–209, NCBI accession number NP_004429, with Cys204 mutated to Ala) and the human ephrin-B2 ectodomain (residues 25–175, accession number NP_004084) were cloned and expressed as described previously (7, 10). An EphA4 mutant in which Gln12 and Glu14 were replaced with Ala (the numbering is according to the EphA4 construct, where the first residue is Asn29) (supplemental Fig. 1) was made using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) and primers 5′-CCA GAT CTG TTG CGG GAG CGC TTG GGT GGA TAG C-3′ and 5′-GCT ATC CAC CCA AGC GCT CCC GCA ACA GAT CTG G-3′. All vectors were transformed into E. coli Rosetta-gami(DE3) cells (Novagen), allowing efficient formation of disulfide bonds and expression of eukaryotic proteins containing codons rarely used in E. coli.

The cells were cultured in LB medium and subsequently induced overnight at 20 °C with 0.4 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside. The harvested cells were sonicated in lysis buffer, and the recombinant proteins were purified by affinity chromatography using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid-agarose (Qiagen). In-gel cleavages by thrombin to release EphA4/mutant and ephrin-B2 were performed at room temperature, and the released proteins were further purified on an AKTA FPLC machine (Amersham Biosciences) using a gel filtration column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200), followed by ion-exchange chromatography on an anion-exchange column (HiTrap Q FF, 5 ml). The eluted fractions containing the EphA4/mutant and ephrin-B2 recombinant proteins were collected and exchanged into a buffer containing 10 mm NaCl, 25 mm Tris-HCl, and 2 mm CaCl2, pH 7.8, for storage. The EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex was prepared by mixing EphA4 and ephrin-B2 at roughly equal molar concentrations and loaded onto a gel filtration column (HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 200). The fraction containing the pure EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex was collected and further concentrated to a final concentration of ∼10 mg/ml.

The isotope-labeled proteins for NMR studies were generated following a similar procedure except that the bacteria were grown in M9 medium with the addition of (15NH4)2SO4 for 15N labeling and (15NH4)2SO4/[13C]glucose for 15N/13C double labeling. The purity of the protein samples was verified by SDS-PAGE, and their molecular weights were confirmed using a Voyager STR matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems). The concentration of protein samples was determined by spectroscopy in the presence of denaturant as described previously (22).

Crystallization, Data Collection, and Structure Determination

The EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex was prepared at a concentration of 10 mg/ml and crystallized by setting up at room temperature over a well 2-μl hanging drops containing 1 μl of EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex and 1 μl of reservoir solution (23.5% polyethylene glycol 4000, 0.1 m Tris, and 0.2 m MgCl2, pH 7.5). Rock-like crystals formed after 7 days. X-ray diffraction images for a single crystal were collected using an in-house Bruker X8 PROTEUM x-ray generator with a CCD detector. The crystal was protected by cryoprotectant (23.5% polyethylene glycol 4000, 0.1 m Tris, and 0.2 m MgCl2, pH 7.5). The data were indexed and scaled in the space group P21 (a = 54.65, b = 48.71, and c = 64.47 Å), with one complex molecule per asymmetric unit, using the program HKL2000 (23). The Matthews coefficient was 2.2 with 44.5% solvent constant.

The initial model of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex was generated by molecular replacement with EphA4 (Protein Data Bank code 3CKH) and ephrin-B2 (code 1KGY) as models using Phaser (24) and MolRep in the Suite CCP4 (25). The complex structure was subsequently completed by manual fitting with the program COOT (26) and further refined through many iterations with CNS (27). The final structure was analyzed by PROCHECK (28), and the details of the data collection and refinement statistics are shown in supplemental Table S1. All figures were prepared using the PyMOL molecular graphics system (DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA). The atomic coordinates of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (code 3GXU).

Binding Characterization by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)4 experiments were performed using a MicroCal VP ITC machine as described previously (7). To use the same condition as for NMR titration, the EphA4/EphA4 mutant receptors and ephrin-B2 ligand were exchanged into 10 mm phosphate buffer with the final pH value adjusted to 6.3. Ephrin-B2 was placed in a 1.8-ml sample cell, and the EphA4/EphA4 mutant receptors were loaded into a 300-μl syringe. To obtain thermodynamic binding parameters, the titration data after subtracting the values of the control experiments were fitted to a single-binding site model using the built-in software ORIGIN Version 5.0 (MicroCal Inc.). The detailed setup and results are documented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Thermodynamic parameters for the binding of wild-type and mutant EphA4 to ephrin-B2 and two small molecule antagonists measured by ITC

All measurements were performed in 10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.2, with an injection volume of 5 μl.

| Syringe | Cell | Ka | Ka | Stoichiometry | ΔS | ΔH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| m−1 | μm | n | cal/mol·K | kcal/mol | ||

| EphA4 (0.2 mm) | Ephrin-B2 (0.01 mm) | 4.93 × 106 ± 0.47 × 106 | 0.203 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 20.9 | −2.89 ± 0.035 |

| Mutant EphA4 (0.6 mm) | Ephrin-B2 (0.03 mm) | 4.2 × 105 ± 0.55 × 105 | 2.35 | 0.92 ± 0.02 | 19.7 | −1.81 ± 0.053 |

| Compound 1 (2 mm)a | EphA4 (0.07 mm) | 4.89 × 104 ± 0.51 × 104 | 20.4 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 18.1 | −1.00 ± 0.027 |

| Compound 1 (2 mm) | Mutant EphA4 (0.07 mm) | 4.95 × 104 ± 0.31 × 104 | 20.2 | 1.20 ± 0.00 | 19.8 | −0.51 ± 0.008 |

| Compound 2 (2 mm)a | EphA4 (0.07 mm) | 3.78 × 104 ± 0.76 × 104 | 26.4 | 1.00 ± 0.00 | 20.1 | −0.24 ± 0.013 |

| Compound 2 (2 mm) | Mutant EphA4 (0.07 mm) | 3.93 × 104 ± 0.21 × 104 | 25.4 | 0.98 ± 0.00 | 20.4 | −0.19 ± 0.003 |

a ITC data for the binding of compounds 1 and 2 to wild-type EphA4 from a previous publication (7) are included for comparison.

Binding Characterization by NMR

NMR samples were also prepared in 10 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.3, with the addition of 10% D2O for NMR spin-lock experiments. All NMR spectra were collected at 25 °C on an 800-MHz Bruker AVANCE spectrometer equipped with a shielded cryoprobe as described previously (7, 10, 29, 30). For the preliminary sequential assignments, triple-resonance NMR spectra, including HNCACB, CBCA(CO)NH, and (H)C(CO)NH, were acquired on a double-labeled EphA4 sample at a concentration of 500 μm. The obtained sequential assignments were further confirmed by analyzing other three-dimensional spectra, including (H)CC(CO)NH, H(CCO)NH, 15N-edited heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) total correlation and HSQC nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopies, and 13C-edited HCCH total correlation and nuclear Overhauser effect spectroscopies. NMR data were processed with NMRPipe (31) and analyzed with NMRView (32).

For NMR characterization of the binding of the EphA4/EphA4 mutant ligand-binding domain to the ephrin-B2 ligand, two-dimensional 1H-15N HSQC spectra of EphA4 were acquired at a protein concentration of 100 μm in the absence or presence of ephrin-B2 at different molar ratios, including 2:1; 1:1, and 1:1.5 (EphA4/ephrin-B2). For mutant EphA4, the HSQC spectra were acquired at molar ratios of 1:1; 1:2, 1:3, 1:4, and 1:8 (EphA4 mutant/ephrin-B2). By superimposing the HSQC spectra, the shifted and disappeared HSQC peaks could be identified and further assigned to the corresponding EphA4 residues (7). The binding of the two small molecule antagonists compound 1 and compound 2 to mutant EphA4 was carried out using our previous protocol except for replacing wild-type EphA4 with mutant EphA4 (7).

Mutagenesis and Expression of Recombinant Proteins in Human Embryonic Kidney Cells

The sequence encoding amino acids 29–209 of the human EphA4 ligand-binding domain with mutation of Cys204 (see above) was amplified by PCR with primers containing NheI and BamHI restriction sites, which allowed cloning into a pcDNA3 vector containing the human CD5 signal peptide (preceding the NheI site) (33). The fragment obtained by digestion with HindIII and BamHI, which contains the EphA4 sequence preceded by the CD5 signal peptide, was cloned in HindIII-BglII-digested pAPtag-2 vector (GenHunter) to produce an alkaline phosphatase (AP) fusion protein (34). Nucleotides 17–692 of the human ephrin-B2 ectodomain sequence (NCBI accession number NM_004093), which encode amino acid residues 1–226 (accession number NP_004084), were similarly cloned into the pAPtag-2 vector. Gln12 and Glu14 in human EphA4 (supplemental Fig. 1) and Glu109 and Lys112 in human ephrin-B2 were mutated to alanine using the QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit following the manufacturer's instructions. Culture medium containing secreted AP fusion proteins was obtained from transiently transfected human embryonic kidney 293 cells as described previously (35). The concentration of the AP fusion proteins was quantified by measuring AP activity (36).

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assays (ELISAs)

Protein A-coated wells (Pierce) were used to immobilize Eph receptor- or ephrin-Fc fusion proteins (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Culture medium containing AP fusion proteins was subsequently added, and after several washes, binding was quantified using p-nitrophenyl phosphate as the substrate. The signal from wells with no AP fusion proteins was subtracted as background. To evaluate the binding affinities of wild-type and mutant EphA4-AP for ephrins and the binding affinities of wild-type and mutant ephrin-B2-AP for Eph receptors, the AP fusion proteins were added to the wells at different concentrations. Dissociation constants (Kd) were calculated using nonlinear regression and GraphPad Prism.

It should be noted that the apparent Kd values measured in the ELISAs are much lower than those obtained by ITC. This is due to the dimeric nature of AP fusion proteins, which therefore have increased avidity. Furthermore, the concentration of fusion proteins calculated based on AP activity may be underestimated (36).

RESULTS

Crystal Structure of the EphA4-Ephrin-B2 Complex

In this study, we determined the crystal structure of the EphA4 ligand-binding domain in complex with the ephrin-B2 ectodomain at 2.5-Åresolution. The details of data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in supplemental Table S1. In the final model, the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex exists as a heterodimer (Fig. 1a), consistent with size-exclusion fast protein liquid chromatography analysis, indicating that the two proteins form a 1:1 heterodimer at concentrations of up to 500 μm (data not shown). Some residues were not detectable in the complex due to poor electron density probably resulting from local flexibility, including EphA4 G-H loop residues Gly85, Val86, and Met87 and H-I loop residue Arg110 (the numbering is according to the residues in the EphA4 construct, where Asn29 is the first residue, as shown in supplemental Fig. 1) and ephrin-B2 C-D loop residues Asp69–Gly74 and Lys96 (the numbering is according to the mouse ephrin-B2 sequence for consistency with previously published structures). Importantly, all EphA4 D-E and J-K loop residues are visible in the complex even though some of them were previously undetectable in the free EphA4 structure (7).

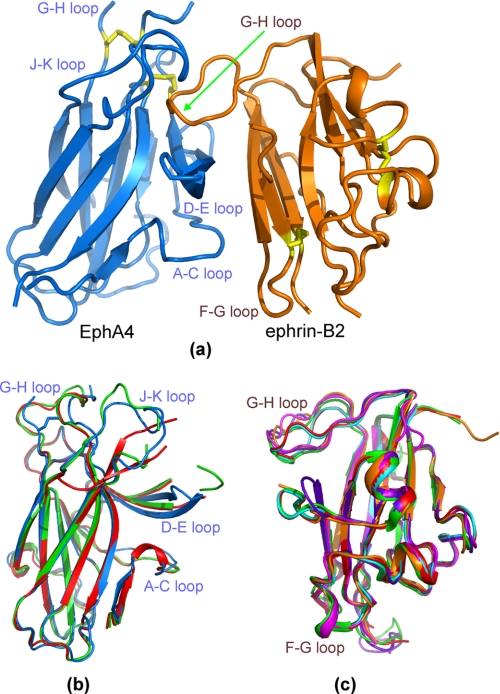

FIGURE 1.

Crystal structure of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex. a, overall structure of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex. Cysteines involved in disulfide bonds (Cys45–Cys163 and Cys80–Cys90 in EphA4 and Cys65–Cys104 and Cys92–Cys156 in ephrin-B2) are indicated in yellow. b, superimposition of the structures of EphA4 in complex with ephrin-B2 (blue) and the previously determined structures of free EphA4 molecule A (green) and molecule B (red) (7). c, superimposition of the structures of ephrin-B2 in complex with EphA4 (brown), EphB2 (purplish blue; Protein Data Bank code 1KGY), EphB4 (violet; code 2HLE), Hendra virus attachment protein (cyan; code 2VSK), and Nipah virus attachment protein (red; code 2VSM) as well as free ephrin-B2 (green; code 1IKO).

The overall structure of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex is architecturally similar to the structures of other Eph-ephrin complexes determined previously, with root mean square deviations of 1.56, 1.98, 1.28, and 2.36 Åover the equivalent Cα positions in the EphB2-ephrin-B2 (4), EphB4-ephrin-B2 (6), EphB2-ephrin-A5 (5), and EphA2-ephrin-A1 (8) complexes, respectively. However, large structural variations were observed in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex compared with other Eph-ephrin complexes over the loop regions directly involved in ephrin binding, which include the EphA4 A-C, D-E, G-H, and J-K loops (Fig. 1b) and the ephrin-B2 G-H loop (Fig. 1c).

We previously determined the crystal structure of the EphA4 ligand-binding domain in the free state and found that there are two conformers (designated as molecules A and B) in one asymmetric unit (7). The two EphA4 molecules are almost superimposable over the whole sequence, except that the J-K loop does not have any regular secondary structure in molecule A but contains a short β-sheet formed by Phe126–Val129 and Met136–Asn139 in molecule B (Fig. 1b). The structure of EphA4 bound to ephrin-B2 does not contain the short β-sheet and is therefore more similar to molecule A than molecule B (Fig. 1b). Indeed, root mean square deviations are 1.08 and 1.13 Åover the equivalent Cα positions of free EphA4 molecules A and B, respectively. Four EphA4 loops (A-C, D-E, G-H, and J-K) undergo substantial movements toward ephrin-B2 upon binding (Fig. 1b). For example, the Cα atom of Glu14 in the A-C loop shifts by 2.08 Å; the Cα atom of Pro84 in the G-H loop shifts by 3.06 Å; and strikingly, the Cα atom of Glu34 in the J-K loop shifts by 10.34 Å.

Ephrin-B2 undergoes less dramatic structural changes upon binding to EphA4. The EphA4-bound ephrin-B2 structure has root mean square deviations of 1.06, 0.91, and 0.80 Åover the equivalent Cα positions of ephrin-B2 in the free state, bound to EphB2, and bound to EphB4, respectively, and of 0.89 and 0.80 Åover the Cα positions of ephrin-B2 bound to the G attachment glycoproteins of the Nipah and Hendra viruses (37), respectively (Fig. 1c). Relatively large conformational changes among different ephrin-B2 structures are observed only in the F-G and G-H loops.

Binding Interface of the EphA4-Ephrin-B2 Complex

The dissociation constant (Kd) for EphA4-ephrin-B2 binding measured by isothermal calorimetry is 203 nm (Fig. 2 and Table 1). This binding affinity is much weaker than that between EphB2 and ephrin-B2 (22 nm) (10) or EphB4 and ephrin-B2 (40 nm) (6), also measured by isothermal calorimetry. To understand the structural basis of the differences in ephrin-B2 binding affinity for EphA4 versus EphB receptors, we performed a detailed analysis of the binding interface between EphA4 and ephrin-B2.

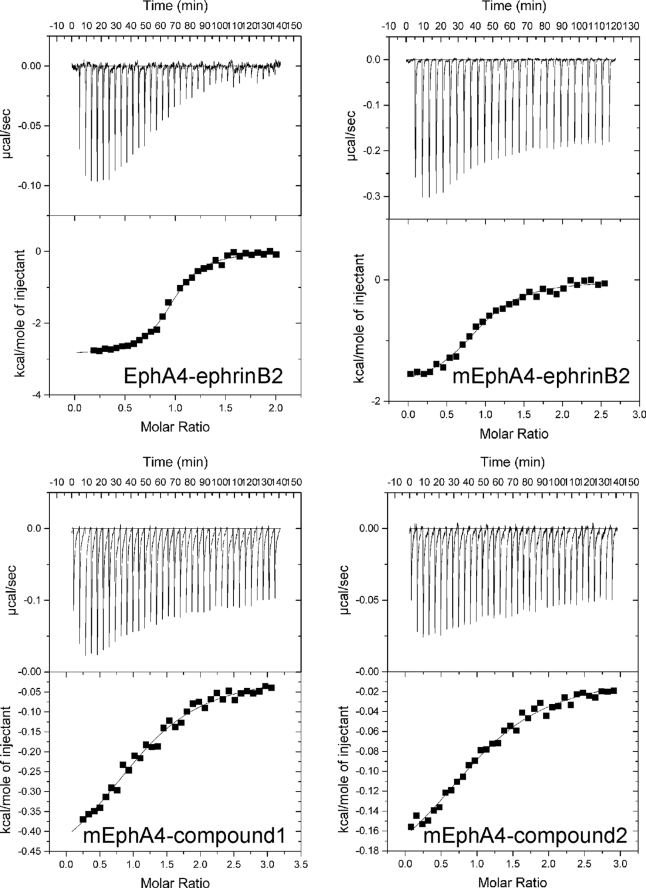

FIGURE 2.

Characterization of EphA4 binding to ephrin-B2 and two small molecule antagonists by isothermal calorimetry. Shown are ITC profiles for the binding reactions of wild-type and mutant EphA4 (mEphA4) with ephrin-B2 and compounds 1 and 2 (upper part of each panel) and plots of the integrated values for the reaction heats (after blank subtraction and normalization to the amount of ligand injected) versus EphA4/ligand molar ratio (lower part of each panel). The results and detailed conditions for the ITC experiments are presented in Table 1 and under “Experimental Procedures.”

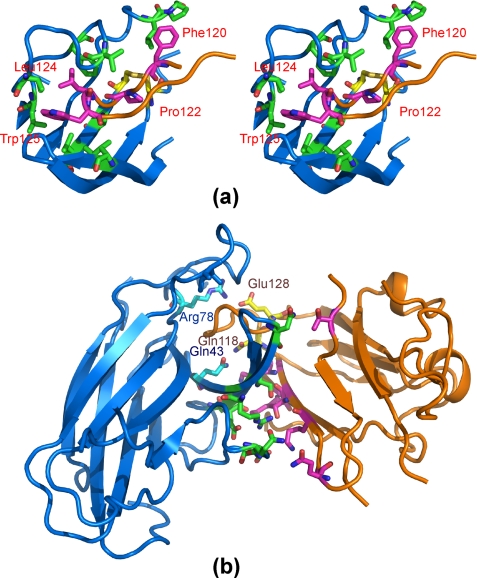

The EphA4-ephrin-B2 interface centers around the ephrin-B2 G-H loop, which is inserted into a hydrophobic channel of the EphA4 receptor, as observed previously for other Eph-ephrin complexes (Fig. 3a). The EphA4 D, E, and J β-strands serve as the sides of the channel, and the G and M strands form the back of the channel, which is further capped by the EphA4 G-H loop. Interactions between the ephrin-B2 G-H loop and the EphA4 channel appear to be dominated by van der Waals contacts. In particular, the side chains of Leu124 and Trp125 at the tip of the ephrin-B2 G-H loop establish extensive hydrophobic interactions with the EphA4 hydrophobic side chains of Ile31 in the D strand; Val167 in the M strand; and Phe126, Val129, Ile135, and Leu138 in J-K loop. Furthermore, the aromatic ring of Phe120L (where L indicates the ligand) establishes hydrophobic interactions with the side chains of Leu83R and Pro84R (where R indicates the receptor). In addition, Pro122L is in direct contact with Ala165 in the M strand of EphA4 as well as the EphA4 disulfide bridge between Cys45 and Cys163. Besides the hydrophobic contacts, there are two polar interactions between EphA4 and ephrin-B2 in the channel. The first is a salt bridge between Glu128L and Arg78R, and the second is a side chain hydrogen bond between Gln118L and Gln43R (Fig. 3b).

FIGURE 3.

Anatomy of the interface between the EphA4 channel and the ephrin-B2 G-H loop. a, stereo pair highlighting hydrophobic interactions between EphA4 and ephrin-B2. The ephrin-B2 hydrophobic residues in the G-H loop are labeled. b, polar interactions between EphA4 and ephrin-B2. The residues involved in polar interactions within the binding channel are labeled. A side chain hydrogen bond is formed between EphA4 Gln43 and ephrin-B2 Gln118, and a side chain salt bridge is formed between EphA4 Arg78 and ephrin-B2 Glu128. For EphA4 residues, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen atoms are colored cyan, blue, and red, whereas for ephrin-B2 residues, they are colored pink, blue, and red, respectively. Disulfide bonds are shown in yellow.

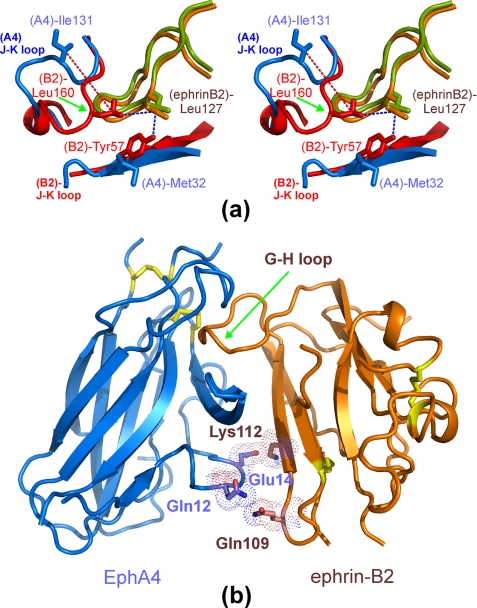

Interestingly, in the previously described EphB2-ephrin-B2 complex (4), Tyr57 in the D strand of mouse EphB2 (corresponding to Tyr50 in the human sequence) (supplemental Fig. 1) engages in aromatic-hydrophobic interactions with Leu160 in the J-K loop of EphB2 and Leu127 in the G-H loop of ephrin-B2 (Fig. 4a). These interactions lead to the formation of a hydrophobic patch, which is absent in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex (Fig. 4a) because the EphA4 residue structurally equivalent to EphB2 Tyr57 is a Met (supplemental Fig. 1). The absence of this hydrophobic patch in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex appears to be responsible for the large 10.3-Åmovement of the EphA4 J-K loop away from ephrin-B2. As a consequence, the J-K loop of EphA4 interacts more loosely with the ephrin-B2 G-H loop than does the J-K loop of EphB2. This may at least in part account for the relatively low binding affinity between EphA4 and ephrin-B2. In the EphB4 receptor, the residue corresponding to EphB2 Tyr57 is also a Met, and the hydrophobic patch observed in the EphB2-ephrin-B2 complex is also absent (6). However, the EphB4 J-K loop forms a short two-stranded β-sheet with a Pro at the β-turn position, which establishes additional contacts with the ephrin-B2 G-H loop, such as those between EphB4 Pro151 and ephrin-B2 Phe120. These additional contacts, together with the other contacts between ephrin-B2 Phe120/Pro122 and EphB4 Leu95 (6), may partly compensate for the absence of the hydrophobic patch and still yield a high binding affinity for the EphB4-ephrin-B2 interaction.

FIGURE 4.

Unique features of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 interclass dimerization interface. a, stereo pair comparing the conformations of the Eph receptor J-K loops in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 and EphB2-ephrin-B2 (Protein Data bank code 1KGY) complexes. A portion of the EphA4 J-K loop is moved away from Leu127 at the tip of the ephrin-B2 G-H loop. b, surface polar contact region identified in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex involving EphA4 residues Gln12 and Glu14 and ephrin-B2 residues Gln109 and Lys112. The region provides additional interactions besides those between the EphA4 channel and the ephrin-B2 G-H loop. Disulfide bonds are shown in yellow.

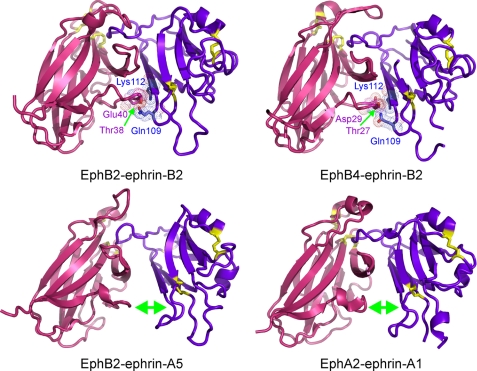

There is also a second contact region in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 interface, structurally separate from the channel and involving extensive surface polar contacts mediated by a network of hydrogen bonds and salt bridges between the upper surface of EphA4 (A-C loop and D and E strands) and the ephrin-B2 C, G, and F strands (Fig. 4b). These polar interactions include hydrogen bonds between Gln109L and Gln12R, Thr114L and Ser30R/Arg40R, Lys60L and Glu28R, Gln118L and Gln43R, and Thr99L and Asn36R as well as salt bridges between Lys112L and Glu14R, Lys116L and Glu27R, and Glu128L and Arg78R. Within this surface contact region, the side chain hydrogen bond between Gln12 in the A-C loop of EphA4 and Gln109 in the F-G loop of ephrin-B2 and the side chain salt bridge between Glu14 in the A-C loop of EphA4 and Lys112 in the G β-strand of ephrin-B2 would be predicted to play a particularly critical role (Fig. 4b). Among the Eph-ephrin complex structures reported so far, similar contacts were observed in the EphB2-ephrin-B2 and EphB4-ephrin-B2 complexes, but not in the EphA2-ephrin-A1 complex or the EphB2-ephrin-A5 interclass complex (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

Structures of the known Eph-ephrin complexes. The surface contact region equivalent to that observed in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex is shown for the EphB2-ephrin-B2 (Protein Data Bank code 1KGY) and EphB4-ephrin-B2 (code 2HLE) complex structures. The EphB2-ephrin-A5 (code 1SHW) and EphA2-ephrin-A1 (code 3CZU) complex structures lack an extensive surface contact region. The receptors are shown in red, and ephrin-B2 is shown in violet; disulfide bonds are shown in yellow.

Ligand Binding Properties of the EphA4 Gln12/Glu14 Mutant

To investigate the contribution of the surface contact region to the binding affinity between EphA4 and ephrin-B2, we replaced residues of EphA4 and ephrin-B2 involved in the interface with alanines. Mutation of Gln12 and Glu14 in the A-C loop of EphA4 did not result in significant overall conformational changes, as judged by circular dichroism and NMR characterization (supplemental Fig. 2, b and c). Nevertheless, the affinity of the EphA4 mutant for ephrin-B2 is ∼10-fold lower than that of wild-type EphA4 (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Interestingly, although the entropy change (ΔS) associated with the binding of ephrin-B2 to mutant EphA4 remains mostly unchanged compared with wild-type EphA4, the enthalpy change (ΔH) is significantly lower. This implies that the hydrophobic interactions between the ephrin-B2 G-H loop and the EphA4 channel are very similar for both wild-type and mutant EphA4. However, mutation of EphA4 Gln12 and Glu14 to Ala disrupts the polar surface interactions with ephrin-B2, thus leading to a significant difference in ΔH (38, 39).

Two small molecule antagonists designated compound 1 and compound 2 were previously found to target the ephrin-binding channel of EphA4, thus antagonizing the binding of several ephrins (7, 40). We found that the Kd and ΔS values for the binding of the two compounds to mutant and wild-type EphA4 are very similar (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Furthermore, the binding of the two compounds perturbs the same residues of wild-type and mutant EphA4 in NMR HSQC titrations (spectra not shown). These results indicate that mutation of Gln12 and Glu14 to Ala does not detectably affect the EphA4 ligand-binding channel, which is the target of the two compounds.

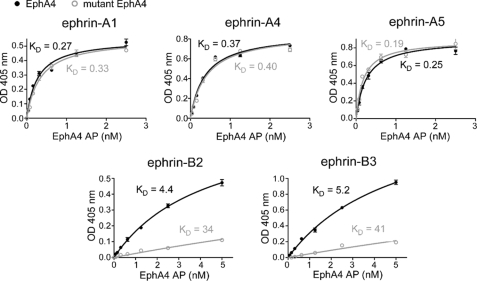

To investigate the contribution of the surface contact region to the binding affinity of EphA4 for different ephrins, we performed ELISAs using the EphA4 ligand-binding domain fused to AP and ephrin-Fc fusion proteins generated in eukaryotic cells. The Kd values for the binding of mutant EphA4 to ephrin-A1, ephrin-A4, and ephrin-A5 are very similar to those of wild-type EphA4, whereas mutant EphA4 shows an ∼10-fold lower affinity for ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3 compared with wild-type EphA4 (Fig. 6). These results clearly indicate that EphA4 Gln12 and Glu14 do not play an important role in the binding of ephrin-A ligands, whereas they are critical for the interclass binding of ephrin-B ligands.

FIGURE 6.

Binding affinities of wild-type and mutant EphA4 for different ephrin ligands. Shown is the binding of different concentrations of EphA4-AP or mutant EphA4 Gln12/Glu14-AP to the indicated ephrin-Fc fusion proteins immobilized on ELISA wells. It should be noted that the Kd values for the binding of mutant EphA4 to ephrin-B2 and ephrin-B3 are approximate because mutant EphA4-AP concentrations sufficiently high to achieve maximal binding to these ephrins could not be achieved due to the low binding affinity. The curves for mutant EphA4-AP were fitted to the maximal binding value (Bmax) calculated from the wild-type EphA4 binding curves (Bmax = 0.55 for ephrin-A1, 0.86 for ephrin-A4, 0.90 for ephrin-A5, 0.88 for ephrin-B2, and 1.9 for ephrin-B3). In the case of the A-type ephrins, the same Bmax values were obtained by fitting the curves for mutant EphA4 without constraining Bmax.

Receptor Binding Properties of the Ephrin-B2 Gln109/Glu112 Mutant

Structural characterization by circular dichroism suggests that ephrin-B2 becomes more helical when Gln109 and Lys112 are mutated to Ala (supplemental Fig. 2a). This is reasonable given that Lys112 is located on the G β-strand and Ala is known to be a helix-inducing residue. Despite these structural changes, the affinity of mutant ephrin-B2 for EphB receptors in ELISAs was reduced by only 2–4-fold compared with wild-type ephrin-B2 (supplemental Fig. 4). This suggests that Gln109 and Lys112 play a relatively minor role in EphB receptor binding and that most of the binding affinity depends on the interaction of the ephrin-B2 G-H loop with the EphB channel. In contrast, the affinity of mutant ephrin-B2 for EphA4 was much more compromised, and the binding was barely detectable (supplemental Fig. 4), consistent with the effect of the complementary mutations in EphA4 and a key importance of the surface contact region in EphA4-ephrin-B2 interclass binding.

NMR Visualization of Structural Perturbations Occurring in EphA4 upon Ephrin-B2 Binding

We also used NMR spectroscopy to gain further insight into the interaction of wild-type and mutant EphA4 with ephrin-B2 in solution. In NMR HSQC titrations, the binding between wild-type EphA4 and ephrin-B2 was saturated at a molar ratio of 1:1.5 (EphA4/ephrin-B2), consistent with the relatively strong binding affinity between the two proteins. Interestingly, upon ephrin-B2 binding, ∼80% of the residues over the whole EphA4 molecule underwent large perturbations, with only a third of the HSQC peaks shifting, whereas the rest disappeared (supplemental Fig. 3a). Although ∼70% of the residues with HSQC peaks that disappeared are located within or closely adjacent to the EphA4-ephrin-B2 interface, others appear randomly distributed over the whole molecule. This implies that the binding to ephrin-B2 provokes significant conformational exchanges in the μs-ms time scale over the whole EphA4 ligand-binding domain, as we previously observed for the Nck2 SH2 (Src homology 2) domain upon binding to the phosphorylated ephrin-B2 cytoplasmic domain (30). Alternatively, formation of high order EphA4-ephrin-B2 heterodimeric complexes might explain the overall perturbations observed. However, this seems unlikely because we detected only heterodimers at the high concentrations used for fast protein liquid chromatography analysis and also at the even higher concentrations used for crystallization.

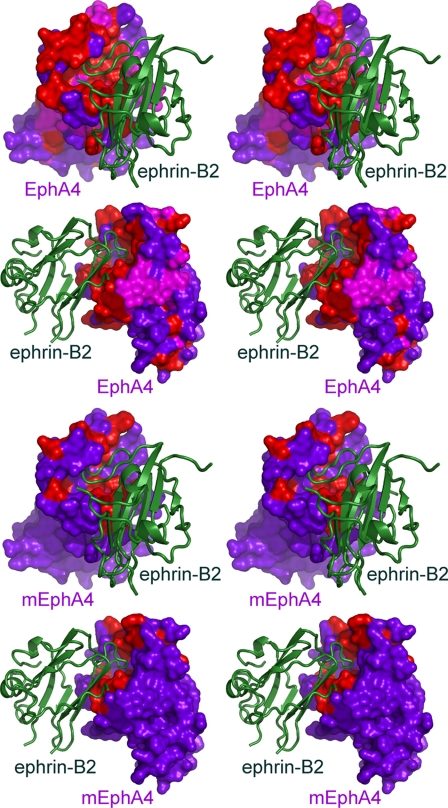

The binding between mutant EphA4 and ephrin-B2 was saturated at a molar ratio of 1:3 (mutant EphA4/ephrin-B2), consistent with the weaker binding between the two proteins. Strikingly, only a small portion of the mutant EphA4 residues were perturbed by the binding of ephrin-B2 (supplemental Fig. 3b). Furthermore, all of the perturbed residues center around the binding interface with the ephrin-B2 G-H loop (Fig. 7). In contrast to wild-type EphA4, residues in the A-C loop of mutant EphA4 were not perturbed even at a molar ratio of 1:8. Almost all of the perturbed residues in mutant EphA4 have direct contacts with ephrin-B2 in the crystal structure (Figs. 3 and 7 and supplemental Fig. 3b). Interestingly, we also observed a significant perturbation of Cys163, which forms a disulfide bond with Cys45. This disulfide bond is conserved in different Eph receptors and has been implicated in the binding of both ephrins and antagonistic peptides (41).

FIGURE 7.

NMR mapping of Eph-ephrin binding interfaces in solution. The stereo pairs show the perturbed residues in wild-type EphA4 and mutant EphA4 (mEphA4) in complex with ephrin-B2, which were mapped using NMR HSQC titrations. The EphA4 residues that are shifted in the complex are colored pink; those that have disappeared are colored red; and those that are unchanged are colored violet. EphA4 is shown in surface mode, and ephrin-B2 is shown as a ribbon.

DISCUSSION

The binding promiscuity between Eph receptors and ephrin ligands appears to be a key strategy enabling Eph-ephrin signaling networks to control a wide array of biological functions. Understanding the structural principles governing promiscuity versus selectivity of Eph receptor-ephrin binding is therefore important for elucidating the mechanisms underlying the biological functions of the Eph system and is also critical for the design of antagonists to target Eph-ephrin interactions. EphA4 is the only Eph receptor that can bind with substantial affinity all ephrin-A and ephrin-B ligands (12). Here, we have reported the structure of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex, which represents the first structure of a complex between an EphA receptor and an ephrin-B ligand.

The overall architecture of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex is very similar to those determined previously for other Eph-ephrin complexes. The high affinity interface of the complex can be divided into two relatively independent regions. One mostly involves the hydrophobic interactions between the EphA4 ligand-binding channel and the ephrin-B2 G-H loop. The other, which was observed in EphB-ephrin-B complexes (4, 6) but was greatly reduced in the EphA2-ephrin-A1 complex and absent in the EphB2-ephrin-A5 complex (5, 8), involves polar interactions between surface residues Gln12 and Glu14 in EphA4 and Gln109 and Lys112 in ephrin-B2. We did not obtain evidence for a distinct lower affinity binding interface that may mediate tetramerization of two EphA4-ephrin-B2 heterodimers similar to that described for the EphB2-ephrin-B2 complex (4). Such an interface is also not evident in the EphB4-ephrin-B2, EphA2-ephrin-A1, and EphB2-ephrin-A5 complexes (5, 6, 8).

Several notable structural variations are observed in EphA4 upon complex formation with ephrin-B2, including those in the D and E β-strands as well as the A-C, D-E, G-H, and J-K loops. Significant structural rearrangements in these regions have also been reported for EphB receptors upon ephrin binding (4, 6, 42). In contrast, only minor structural changes have been observed upon formation of the EphA2-ephrin-A1 complex (8).

The EphA4-ephrin-B2 structure also explains the relatively weak affinity of the EphA4-ephrin-B2 interclass binding (Kd = 203 nm) compared with intraclass interactions, such as those of EphB2 with ephrin-B2 (Kd = 22 nm) and EphB4 with ephrin-B2 (Kd = 40 nm). Because of sequence variations, a hydrophobic patch present in the EphB2-ephrin-B2 complex is absent in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex. As a consequence, half of the EphA4 J-K loop remains open and does not make any contacts with the ephrin-B2 G-H loop (Fig. 4a). Given that the structurally equivalent EphB2 loop region is more open in the complex with ephrin-A5 and that the binding affinity of EphB2 for ephrin-A5 is even lower (Kd = 320 nm) (5), this feature likely accounts at least in part for the low binding affinity between EphA4 and ephrin-B2. However, comparing Kd values for wild-type and mutant proteins shows that the surface contacts formed between EphA4 residues Gln12 and Glu14 and ephrin-B2 residues Gln109 and Lys112 increase by ∼10-fold the binding affinity and thus play a critical role in EphA4-ephrin-B2 interclass binding.

Mutation of the two EphA4 residues involved in the interface yields an EphA4 mutant that does not appear to undergo global structural changes or modifications in the ephrin-binding channel. This is evident from the unchanged binding affinity of the EphA4 mutant for two small molecule antagonists that bind within the channel. Interestingly, the polar surface contact region of EphA4 does not appear to be necessary for the intraclass binding with ephrin-A ligands, which probably involves a more intimate fit between the EphA4 ligand-binding channel and the ephrin-A G-H loop. This is the case for the EphA2-ephrin-A1 complex, where the surface contact region is extremely reduced (8). Similarly, this region is likely not present or minimal in EphA4-ephrin-A complexes.

On the other hand, Gln109 and Lys112 of ephrin-B2 have been shown to also interact with residues on the surface of EphB receptors (4, 6), which could explain the 2–3-fold decrease in the affinity of mutant ephrin-B2 for EphB receptors. However, we cannot exclude that the decrease in binding may be due to the changes in the overall conformation of the mutant ephrin observed by CD spectroscopy. Nevertheless, the much more pronounced impairment in the binding of mutant ephrin-B2 to EphA4 than to EphB receptors suggests that the surface contact region is much more critical for the EphA4-ephrin-B2 interclass binding than the EphB-ephrin-B2 intraclass binding. Interestingly, the residue corresponding to ephrin-B2 Gln109 is a Leu in ephrin-B3 and therefore cannot be involved in the hydrogen bond with EphA4 Gln12 that is instead present in the EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex. However, the binding affinity of the EphA4 mutant for ephrin-B2 or ephrin-B3 is equally reduced compared with wild-type EphA4, suggesting that the salt bridge between ephrin-B2 Lys112 and EphA4 Gln14 might play a more important role in EphA4-ephrin-B interclass binding than the hydrogen bond between ephrin-B2 Gln109 and EphA4 Gln12.

NMR characterization also provides the first insight into the dynamic aspects associated with EphA4-ephrin-B2 binding in solution, which could not be achieved from analysis of the more static crystallized complex. Interestingly, the NMR results show that many EphA4 residues perturbed upon ephrin-B2 binding (corresponding to HSQC peaks that shift or disappear) are located outside the high affinity EphA4-ephrin-B2 binding interface. For example, many residues in the EphA4 L and H strands are significantly perturbed even though they are far away from the binding interface. Interestingly, in the crystal structure, these residues do not appear to undergo any detectable conformational changes upon ephrin-B2 binding (Fig. 1b). In contrast, once the interactions mediated by EphA4 Gln12 and Glu14 are removed, the residues perturbed by the binding of ephrin-B2 are limited only to the EphA4 interface in direct contact with ephrin-B2. Thus, contacts mediated by Gln12 and/or Glu14 have far-reaching effects over the entire EphA4 ligand-binding domain. It is tempting to speculate that these perturbations, involving peak shifts and disappearances, may reflect dynamic changes in EphA4 that are initiated by ephrin-B binding and are critical for biological function. However, although we did not obtain evidence for complexes larger than heterodimers, it cannot be completely excluded that a very weak tendency might exist for EphA4-ephrin-B2 heterodimeric complexes to form high order complexes such as tetramers, in analogy to what is observed with EphB2-ephrin-B2 complexes (4). It will be interesting to investigate this possibility in future NMR studies as exemplified previously (43).

The new EphA4-ephrin-B2 complex structure that we have characterized, together with those determined previously for other Eph receptor-ephrin pairs, highlights a surprising diversity in the use of the two regions of the high affinity interface to accomplish intraclass or interclass Eph receptor-ephrin binding. For example, it appears that intraclass binding is mediated almost exclusively (A class) or predominantly (B class) by the hydrophobic Eph channel-ephrin G-H loop region of the interface. Accordingly, the fit of the ephrin G-H loop into the Eph channel is more intimate for the A than the B class. EphB2-ephrin-A5 interclass binding relies only on the channel region of the interface, although the loose interclass fit of the EphB channel and the ephrin-A G-H loop results in the lowest binding affinity among the complexes structurally characterized so far. Interestingly, we found that EphA4-ephrin-B2 interclass binding uses a unique strategy, where the presumably very weak binding through the Eph channel-ephrin G-H loop is supplemented by interactions in the polar surface contact region of the interface. In this manner, EphA4 achieves the highest promiscuity among the Eph receptors.

As a consequence of this variability in Eph receptor-ephrin interfaces, the design of antagonists to target Eph-ephrin interactions may be more challenging than previously thought, and diverse strategies may be needed depending on the Eph receptor and the ephrin involved. Consistent with this notion, we previously found that two small molecule antagonists that target the ephrin-binding channel of EphA4 inhibit the binding of some ephrins but not others. For example, we did not detect inhibition of ephrin-B2 and ephrin-A4 binding to EphA4 at concentrations that completely inhibited the binding of other ephrins (40). The structural information we obtained and the effects of the EphA4 and ephrin-B2 mutations also suggest that it is possible to selectively inhibit EphA4 binding to ephrin-B but not ephrin-A ligands by disrupting the polar surface region of the high affinity interface, whereas the binding of ephrin-A ligands to EphA4 may be selectively inhibited by disrupting appropriate contacts in the channel region. Such strategies may help dissect the biological roles of intraclass versus interclass EphA4-ephrin binding and guide more selective approaches for the design of EphA4 inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA116099 and HD25938 (to E. B. P.). This work was also supported by Singapore National Medical Research Council Grants NMRC/1216/2009 and NMRC/1126/2007 (to J. S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1–4 and Table S1.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (code 3GXU) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- AP

- alkaline phosphatase

- ELISA

- enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pasquale E. B. (2005) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 462–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pasquale E. B. (2008) Cell 133, 38–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himanen J. P., Henkemeyer M., Nikolov D. B. (1998) Nature 396, 486–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Himanen J. P., Rajashankar K. R., Lackmann M., Cowan C. A., Henkemeyer M., Nikolov D. B. (2001) Nature 414, 933–938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Himanen J. P., Chumley M. J., Lackmann M., Li C., Barton W. A., Jeffrey P. D., Vearing C., Geleick D., Feldheim D. A., Boyd A. W., Henkemeyer M., Nikolov D. B. (2004) Nat. Neurosci. 7, 501–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chrencik J. E., Brooun A., Kraus M. L., Recht M. I., Kolatkar A. R., Han G. W., Seifert J. M., Widmer H., Auer M., Kuhn P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 28185–28192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin H., Shi J., Noberini R., Pasquale E. B., Song J. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29473–29484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Himanen J. P., Goldgur Y., Miao H., Myshkin E., Guo H., Buck M., Nguyen M., Rajashankar K. R., Wang B., Nikolov D. B. (2009) EMBO Rep. 10, 722–728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toth J., Cutforth T., Gelinas A. D., Bethoney K. A., Bard J., Harrison C. J. (2001) Dev. Cell. 1, 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ran X., Qin H., Liu J., Fan J. S., Shi J., Song J. (2008) Proteins 72, 1019–1029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith F. M., Vearing C., Lackmann M., Treutlein H., Himanen J., Chen K., Saul A., Nikolov D., Boyd A. W. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 9522–9531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasquale E. B. (2004) Nat. Neurosci. 7, 417–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prévost N., Woulfe D. S., Jiang H., Stalker T. J., Marchese P., Ruggeri Z. M., Brass L. F. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 9820–9825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith A., Robinson V., Patel K., Wilkinson D. G. (1997) Curr. Biol. 7, 561–570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu Q., Mellitzer G., Robinson V., Wilkinson D. G. (1999) Nature 399, 267–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrios A., Poole R. J., Durbin L., Brennan C., Holder N., Wilson S. W. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 1571–1582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kullander K., Mather N. K., Diella F., Dottori M., Boyd A. W., Klein R. (2001) Neuron 29, 73–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kullander K., Croll S. D., Zimmer M., Pan L., McClain J., Hughes V., Zabski S., DeChiara T. M., Klein R., Yancopoulos G. D., Gale N. W. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 877–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yokoyama N., Romero M. I., Cowan C. A., Galvan P., Helmbacher F., Charnay P., Parada L. F., Henkemeyer M. (2001) Neuron 29, 85–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kullander K., Butt S. J., Lebret J. M., Lundfald L., Restrepo C. E., Rydström A., Klein R., Kiehn O. (2003) Science 299, 1889–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benson M. D., Romero M. I., Lush M. E., Lu Q. R., Henkemeyer M., Parada L. F. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 10694–10699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pace C. N., Vajdos F., Fee L., Grimsley G., Gray T. (1995) Protein Sci. 4, 2411–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2005) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 61, 458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collaborative Computational Project Number 4 (1994) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 50, 760–76315299374 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Laskowski R. A., MacArthur M. W., Moss D. S., Thornton J. M. (1993) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 26, 283–291 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sattler M., Schleucher J., Griesinger C. (1999) Prog. NMR Spectrosc. 34, 93–158 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ran X., Song J. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 19205–19212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., Bax A. (1995) J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson B. A., Blevins R. A. (1994) J. Biomol. NMR 4, 603–614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shao H., Lou L., Pandey A., Pasquale E. B., Dixit V. M. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 26606–26609 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheng H. J., Nakamoto M., Bergemann A. D., Flanagan J. G. (1995) Cell 82, 371–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Menzel P., Valencia F., Godement P., Dodelet V. C., Pasquale E. B. (2001) Dev. Biol. 230, 74–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flanagan J. G., Cheng H. J., Feldheim D. A., Hattori M., Lu Q., Vanderhaeghen P. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 327, 19–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bowden T. A., Aricescu A. R., Gilbert R. J., Grimes J. M., Jones E. Y., Stuart D. I. (2008) Nat. Struct Mol. Biol. 15, 567–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Velazquez-Campoy A., Leavitt S. A., Freire E. (2004) Methods Mol. Biol. 261, 35–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lafont V., Armstrong A. A., Ohtaka H., Kiso Y., Mario Amzel L., Freire E. (2007) Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 69, 413–422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Noberini R., Koolpe M., Peddibhotla S., Dahl R., Su Y., Cosford N. D., Roth G. P., Pasquale E. B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 29461–29472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chrencik J. E., Brooun A., Recht M. I., Nicola G., Davis L. K., Abagyan R., Widmer H., Pasquale E. B., Kuhn P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36505–36513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldgur Y., Paavilainen S., Nikolov D., Himanen J. P. (2009) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 65, 71–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jee J., Ishima R., Gronenborn A. M. (2008) J. Phys. Chem. B 112, 6008–6012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.