Abstract

Src kinases are key regulators of cellular proliferation, survival, motility, and invasiveness. They play important roles in the regulation of inflammation and cancer. Overexpression or hyperactivity of c-Src has been implicated in the development of various types of cancer, including lung cancer. Src inhibition is currently being investigated as a potential therapy for non-small cell lung cancer in Phase I and II clinical trials. The mechanisms of Src implication in cancer and inflammation are linked to the ability of activated Src to phosphorylate multiple downstream targets that mediate its cellular effector functions. In this study, we reveal that inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS), an enzyme also implicated in cancer and inflammation, is a downstream mediator of activated Src. We elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the association between Src and iNOS in models of inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide and/or cytokines and in cancer cells and tissues. We identify human iNOS residue Tyr1055 as a target for Src-mediated phosphorylation. These results are shown in normal cells and cancer cells as well as in vivo in mice. Importantly, such posttranslational modification serves to stabilize iNOS half-life. The data also demonstrate interactions and co-localization of iNOS and activated Src under inflammatory conditions and in cancer cells. This study demonstrates that phosphorylation of iNOS by Src plays an important role in the regulation of iNOS and nitric oxide production and hence could account for some Src-related roles in inflammation and cancer.

Introduction

Src kinases are non-receptor tyrosine kinases and key regulators of cellular proliferation, survival, motility, and invasiveness (1). Thus, they play important roles in the regulation of both inflammation and cancer. Overexpression or hyperactivity of c-Src has been implicated in the development of numerous human cancers, including cancer of the lung, prostate, pancreas, breast, and colon (2). Src is also implicated in signaling through both pro- and antiinflammatory cytokines (3). Strategies to modulate Src activity have been suggested as therapeutic modalities for cancer and for chronic inflammatory states (2, 3). More specifically, Src was found to be activated in non-small cell (NSC)3 lung cancer and promoted the survival of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-dependent cancer cell lines (4). Src inhibition is currently being investigated as a potential therapy for NSC lung cancer, and several such products are already in Phase I and II clinical trials (2).

The mechanism of Src implication in cancer and inflammation is linked to the ability of activated Src to phosphorylate multiple downstream targets that mediate its cellular effector functions. Such mediators have included EGFR, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT3), and Bcl-XL (4). In this study, we reveal that inducible nitric-oxide synthase (iNOS), an enzyme also implicated in cancer and inflammation, is a downstream mediator of activated Src. We elucidate the molecular mechanisms of the association between Src and iNOS in models of inflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and/or cytokines and in cancer cells and tissues.

Nitric oxide (NO) plays a critical role in cell metabolism as a multifunctional biological messenger (5). As a signaling molecule, NO is produced by two constitutive isoforms, neuronal NOS and endothelial NOS (or NOSI and NOSIII, respectively) (6). As an agent of inflammation and cell-mediated immunity, NO is produced by a cytokine-inducible NOS (iNOS or NOSII) that is widely expressed in diverse cell types under transcriptional regulation by inflammatory mediators (7, 8). iNOS is induced in many inflammatory syndromes and in septic shock (7, 9). More recently, iNOS up-regulation has been shown to associate with various types of cancer, including NSC lung cancer (10). Correlation between iNOS levels and progression of some cancers has been described (11, 12). The underlying mechanisms of iNOS up-regulation in cancer are not clear, but they include potential roles in cell survival and in angiogenesis. Such a strong correlation between iNOS and cancer has produced a corresponding interest in understanding the regulation of NO synthesis by iNOS with the goal of developing therapeutic strategies aimed at selective modulation of iNOS activity.

Studies on the constitutive NOS isoforms showed that these enzymes are tightly regulated by posttranslational modifications, including phosphorylation (13). Few studies have addressed the potential regulation of iNOS by phosphorylation (14, 15). They showed tyrosine phosphorylation of iNOS by Src and further suggested an increase in iNOS level by Src co-transfection (14). However, direct identification of iNOS residues phosphorylated by Src and the cellular role for such modifications remain unknown. Here, we report the identification of human iNOS residue Tyr1055 as a target for Src-mediated phosphorylation. These results are shown in normal cells and cancer cells as well as in vivo in mice. Importantly, our results indicate that such posttranslational modification serves to stabilize iNOS half-life and hence increase cellular NO production. This study demonstrates that phosphorylation of iNOS by Src plays an important role in the regulation of iNOS and NO production. It also demonstrates interactions and co-localization of iNOS and activated Src under inflammatory conditions and in cancer cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture, transfection, iNOS induction, cell lysis, iNOS activity assays, Western blot analysis, immunoprecipitation, immunofluorescence, and pulse-chase analysis were done as described previously (16–18) and are included in the supplemental materials. Reagents used, real time PCR, and mass spectrometry analysis are also included in the supplemental materials.

Mouse Model of Sepsis

All animal experiments were approved by the institutional requirements in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. Mice (male, C57BL/6, 20–25 g, age 8–12 weeks) were injected intraperitoneally with 200 μl of either phosphate-buffered saline or Escherichia coli LPS (1 mg/kg). At ∼8 h after injection, these mice were used for experiments.

Statistical Analysis

Results are expressed as means ± S.D. of at least three independent experiments. Student's t test was used to evaluate significance, and p values < 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

iNOS Is Phosphorylated on a Tyrosine Residue

Prior studies suggested that iNOS is subject to tyrosine phosphorylation (14, 15). To confirm and extend these findings, we evaluated iNOS phosphorylation in several cellular models. We examined iNOS following its transfection in HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells are human embryonic kidney cells that do not contain any of the NOS genes and therefore have been used extensively to study regulation of exogenously expressed iNOS (16, 19, 20). We also examined cytokine-induced iNOS in human alveolar type II epithelium-like lung carcinoma cell line (A549 cells), human bladder transitional cell papilloma cell line (RT4 cells), and primary normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells. Murine iNOS was evaluated in macrophage cell line RAW264.7 stimulated with LPS. Using the above cellular models, cells were lysed, and iNOS was purified by immunoprecipitation using iNOS-specific antibody and then analyzed by Western blotting with phosphotyrosine (pY) antibodies. These experiments revealed that iNOS was tyrosine-phosphorylated in all cells examined (Fig. 1A). To confirm the specificity of these findings, incubation of immunoprecipitated iNOS in the presence of the tyrosine phosphatase leukocyte common antigen-related protein resulted in decrease in iNOS phosphorylation (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, we conducted experiments in which tyrosine phosphorylation in cultured cells was enhanced by the addition of the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitors sodium orthovanadate (o-van) or pervanadate (PV) (21). Addition of o-van or PV to cultured cells substantially increased iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 1C). Because these phosphatase inhibitors are also known to activate Src kinase (14), among other targets, we investigated potential Src involvement in iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation.

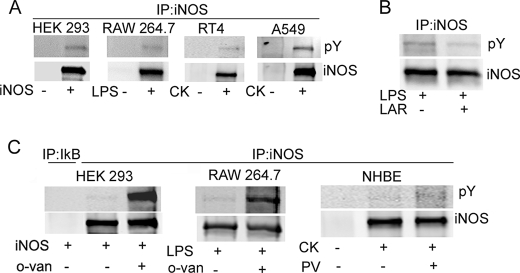

FIGURE 1.

iNOS is tyrosine-phosphorylated. A, HEK293 cells were transfected for 24 h with a plasmid encoding cDNA of human iNOS. RAW264.7 cells were stimulated for 12 h by 100 ng/ml LPS. RT4 cells, A549 cells, and primary NHBE cells were stimulated for 18 h by a cytokine mixture of interferon-γ (100 units/ml; 500 units/ml for A549), interleukin-1β (0.5 ng/ml), and tumor necrosis factor-α (10 ng/ml). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with iNOS antibody followed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against phosphotyrosine (pY) or iNOS. B, immunoprecipitated iNOS, from RAW264.7 cells, was incubated with 10 units of leukocyte common antigen-related protein-tyrosine phosphatase for 30 min prior to Western blot analysis. C, prior to immunoprecipitation, iNOS-transfected HEK293 cells or LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells were incubated with 10 mm sodium o-van for 4 h or 1 h, respectively. Cytokine-stimulated NHBE cells were incubated with 100 μm PV for 30 min prior to immunoprecipitation.

iNOS Is a Target for Src-dependent Tyrosine Phosphorylation

To characterize the role of Src in tyrosine phosphorylation of iNOS, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with iNOS and Src. Src co-transfection led to an increase in iNOS steady-state level and NO production (Fig. 2, A and B). These data are consistent with a prior study indicating an increase in iNOS level caused by Src co-transfection (14). The increase in iNOS level, in Src-transfected cells, was not due to an increase in iNOS mRNA because real time PCR analysis did not show an increase but rather showed a paradoxical reduction in iNOS mRNA (Fig. S1). To investigate whether Src is responsible for iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation, immunoprecipitated iNOS was evaluated for tyrosine phosphorylation with phosphotyrosine antibodies. Src co-transfection resulted in an increase in iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). However, because of the concomitant increase in iNOS level caused by Src, these data cannot distinguish a mere increase in iNOS phosphorylation from an increase in phosphorylated iNOS simply as a consequence of an increase in total iNOS. The above data, however, implied that Src might interact with iNOS. To investigate such an interaction, we used co-immunoprecipitation analysis on transfected cell lysates. When Src was immunoprecipitated, iNOS protein was co-precipitated and detected in the precipitate by immunoblotting (Fig. 2D). These data suggested that Src interacted with iNOS and thus might be responsible for iNOS phosphorylation. To confirm the Src role in iNOS phosphorylation, HEK293 cells, co-transfected with iNOS and Src as above, were incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of the Src inhibitor 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d] pyrimidine (PP2) (22). Src inhibition markedly reduced tyrosine-phosphorylated iNOS, as detected by co-immunoprecipitation (Fig. 2E), confirming the role of Src in iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation. To confirm this observation in cells, not transfected with exogenous Src, we tested the effect of PP2 on PV-induced iNOS phosphorylation in HEK293 cells transfected only with iNOS. Src inhibitor PP2 markedly attenuated PV induction of iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2F), suggesting that PV enhancement of iNOS phosphorylation is mediated through Src kinase. Finally, in vitro incubation of Src with purified iNOS resulted in marked iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2G). The above data collectively demonstrate that Src interacts with and phosphorylates iNOS.

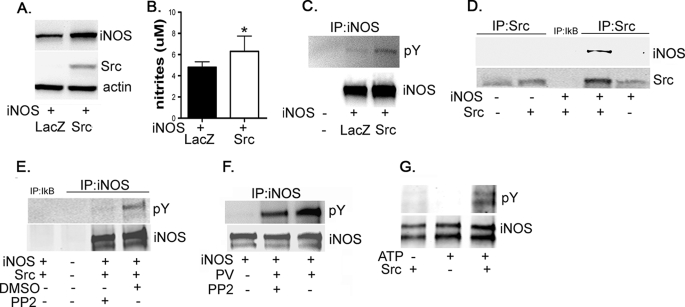

FIGURE 2.

iNOS is regulated by Src-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation. A and B, exogenous expression of Src kinase increases iNOS steady-state level. HEK293 cells were co-transfected, in a 1:1 molar ratio, with plasmids encoding cDNA of human iNOS and with either Src kinase or LacZ, as a control. A, 24 h after transfection, cells were lysed, and aliquots of lysates were subjected to Western blotting with antibodies against iNOS, Src, or β-actin. B, NO production by iNOS was evaluated by measuring nitrite accumulation in culture media. Data represent mean ± S.D., n = 6. *, p < 0.05 compared with control condition. C, Src induces iNOS phosphorylation in cultured cells. Aliquots of lysates were also used for immunoprecipitation (IP) with iNOS antibody followed by Western blotting using phosphotyrosine (pY) antibody. To verify the stringency of immunoprecipitation, HEK293 cells that do not express iNOS were used as a negative control. D, Src interacts with iNOS. The remainder of cell lysates was subjected to immunoprecipitation with Src antibody and analyzed by Western blotting using antibodies against Src or iNOS. To verify the stringency of immunoprecipitation, experiments included samples in which immunoprecipitation antibody was replaced with irrelevant antibody (anti-IκB-β, middle lane). E and F, iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation is attenuated by Src inhibition. E, HEK293 cells were co-transfected as in A, except that the Src kinase inhibitor PP2 (20 μm) or its vehicle dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to culture media 6 h prior to cell lysis. F, HEK293 cells were transfected with human iNOS cDNA. Twenty-four hours after transfection and prior to cell lysis, cells were sequentially incubated in the presence or absence of PP2 (20 μm; 30 min) followed by the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor PV (100 μm for 30 min). Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with iNOS antibody followed by Western blotting with pY antibody. G, Src induces iNOS phosphorylation in vitro. Human iNOS, purified by immunoprecipitation from iNOS-transfected HEK293 cells, was incubated in the presence or absence of Src (100 ng) and ATP (100 μm) for 20 min at 30 °C and then analyzed by Western blotting using iNOS or pY antibodies.

iNOS Is Phosphorylated on Residue Tyr1055

To determine the iNOS tyrosine residue phosphorylated, iNOS was purified by immunoprecipitation from RAW264.7 cells, stimulated overnight with LPS to induce iNOS, and then incubated with 100 μm PV for 30 min to enhance iNOS phosphorylation. iNOS was then analyzed using nano-high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, which indicated phosphorylation on the Tyr1049 residue (Fig. S2). This tyrosine residue is highly conserved among NOSs and various species and is the cognate residue for human Tyr1055 (Fig. S3).

To facilitate the study of iNOS Tyr1055 phosphorylation, we used an iNOS peptide containing a phosphorylated Tyr1055 to produce a specific antibody (pY1055) that recognizes iNOS phosphorylated on Tyr1055. We then utilized pY1055 antibody to examine iNOS phosphorylation in various cell types. Efficiency of iNOS production in these cells was confirmed by Western blotting of cell lysates with iNOS antibodies (Fig. 3A). We then used pY1055 antibody to immunoprecipitate phosphorylated iNOS, which was then evaluated by Western blotting using iNOS antibody (Fig. 3B). We detected Tyr1055-phosphorylated iNOS in HEK293 cells transfected with iNOS, in LPS-stimulated RAW264.7 cells, in cytokine-stimulated A549 or RT4 cells lines, and more importantly, in cytokine-stimulated NHBE cells.

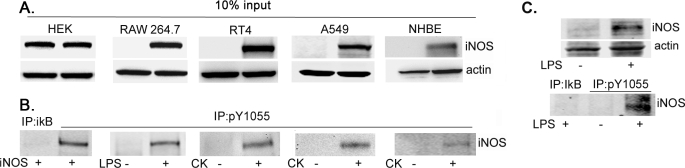

FIGURE 3.

iNOS is phosphorylated on residue Tyr1055. HEK293 cells were transfected for 24 h with a plasmid encoding cDNA of human iNOS. RAW264.7 cells were stimulated for 12 h by 100 ng/ml LPS. RT4 cells, A549 cells, and primary NHBE were stimulated for 18 h by a cytokine mixture of interferon-γ, interleukin-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α. A, aliquots of cell lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis using iNOS or β-actin antibodies. B, the remainder of cell lysates was subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with an antibody against Tyr1055-phosphorylated iNOS (pY1055) followed by Western blotting using iNOS antibodies. To verify the stringency of immunoprecipitation, experiments included samples in which immunoprecipitation antibody was replaced with irrelevant antibody (anti-IκB-β). C, mice were injected intraperitoneally with either LPS (1 mg/kg) or vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline) and sacrificed 18 h later, and their lungs were dissected. Tissue lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis with antibodies against iNOS or β-actin (upper panel). Another part of lysates was subjected to immunoprecipitation with pY1055 antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting using anti-iNOS antibodies (lower panel).

To determine whether iNOS was tyrosine-phosphorylated in vivo, we examined iNOS phosphorylation in a mouse model of sepsis. We evaluated lung homogenates of mice injected for 18 h with LPS or with vehicle only. In LPS-injected mice, but not in vehicle-injected mice, phosphorylated iNOS was clearly immunoprecipitated with pY1055 antibody (Fig. 3C). The detection of Tyr1055-phosphorylated iNOS in various human and murine cell types, as well as in vivo, implied an in important role of Tyr1055 phosphorylation in iNOS biology. We therefore designed experiments to study the effects of Tyr1055 phosphorylation on iNOS.

Characterization of Human iNOS Tyr1055 Phosphorylation

To study the functional role of Tyr1055 phosphorylation, we engineered a human iNOS plasmid in which Tyr1055 was subjected to a conservative point mutation to phenylalanine (Y1055F). We then examined iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation in HEK293 cells transfected with wild-type iNOS or with the Y1055F iNOS mutant. Immunoprecipitation, performed on cell lysates using pY1055 antibody, pulled down iNOS only in cells transfected with wild-type iNOS but not in cells transfected with the Y1055F mutant (Fig. 4A). These results indicated that pY1055 antibody, when used in immunoprecipitation, is highly specific for Tyr1055-phosphorylated iNOS. They also confirm the mass spectrometry data obtained above, showing that iNOS is tyrosine-phosphorylated on residue Tyr1055. We also evaluated the above cell lysates for general tyrosine phosphorylation of iNOS using pY antibody, as used above in Fig. 1, which can detect any phosphorylated tyrosine residue.

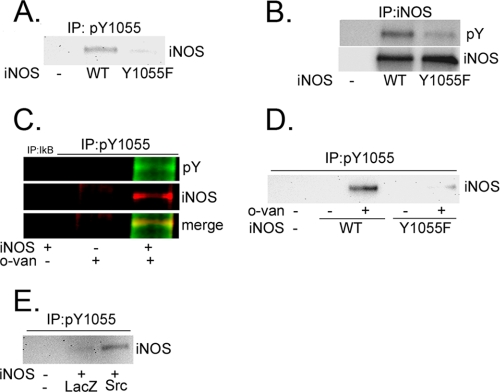

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of Human iNOS Tyr1055 phosphorylation. A and B, Y1055F mutation reduces iNOS phosphorylation. HEK293 cells were either not transfected or were transfected for 24 h with plasmids encoding cDNAs of wild-type (WT) iNOS or iNOS mutant Y1055F. Cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with Tyr1055-phosphoryated iNOS (pY1055) (A) or iNOS (B) antibodies. Aliquots of immunoprecipitation were subjected to Western blotting using iNOS (A) or pY (B) antibodies. C and D, o-van increases iNOS Tyr1055 phosphorylation. C, HEK293 cells were transfected, for 24 h, with a plasmid encoding iNOS cDNA and then incubated in the presence or absence of 10 mm o-van for 4 h. Cells were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation using pY1055 antibody followed by Western blotting using iNOS or pY antibodies. To verify the stringency of immunoprecipitation, experiments included samples where immunoprecipitation antibody was replaced with irrelevant antibody (anti-IκB-β), or immunoprecipitation was done on lysates of HEK293 cells not transfected with iNOS. D, HEK293 cells were transfected as in A and then incubated in the presence or absence of 10 mm o-van for 4 h. Cells were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation with pY1055 antibody followed by Western blotting with iNOS antibody. E, Src kinase increases iNOS Tyr1055 phosphorylation. HEK293 cells were co-transfected for 24 h, in a 1:1 molar ratio, with plasmids encoding human iNOS and either Src or LacZ as a control. Cell lysates were used for immunoprecipitation with pY1055 antibody followed by Western blotting with iNOS antibody.

Whereas pY antibody readily detected tyrosine phosphorylation of wild-type iNOS, there was close to complete elimination of detected tyrosine phosphorylation in Y1055F iNOS mutant (Fig. 4B), suggesting that residue Tyr1055 is the major site for iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation. Nevertheless, the data do not rule out that tyrosine phosphorylation may occur on other iNOS residues, albeit to a much less extent. Our earlier data above in Fig. 1C suggested that tyrosine phosphorylation of iNOS was enhanced in cultured cells by the addition of the tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor o-van. In similar experiments, o-van greatly enhanced phosphorylation of iNOS on residue Tyr1055 (Fig. 4C). The specificity of this observation was confirmed by the absence of a similar effect by o-van on the Y1055F iNOS mutant (Fig. 4D). Because the phosphatase inhibitor o-van activates Src, these data implicated Src in mediating iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation on Tyr1055. Consistent with this hypothesis, exogenous expression of Src markedly enhanced iNOS Tyr1055 phosphorylation (Fig. 4E). Altogether, these data indicate that residue Tyr1055 in iNOS is a target of Src tyrosine kinase-mediated phosphorylation.

Src-mediated iNOS Tyr1055 Phosphorylation Serves to Stabilize iNOS Half-life

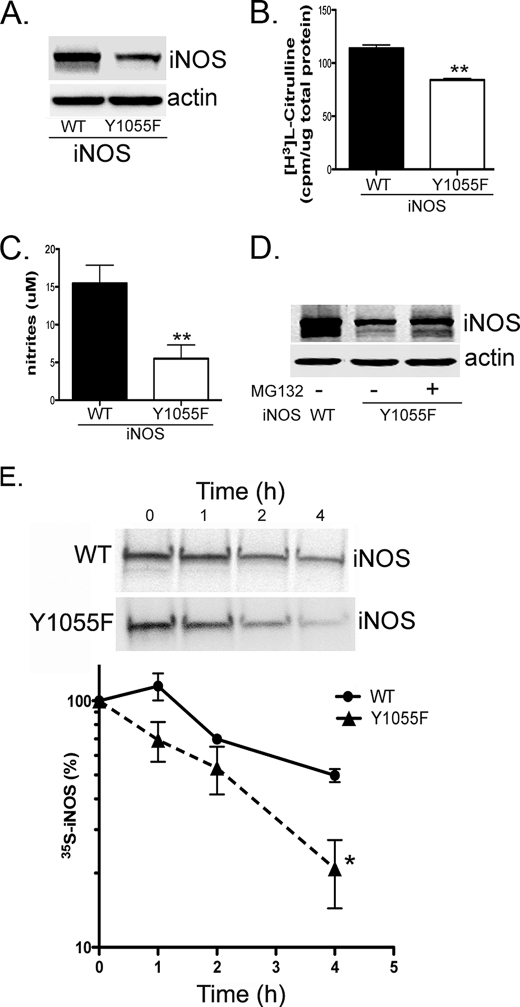

Our earlier data above showed that Src co-expression led to a posttranscriptional increase in iNOS level and greatly enhanced iNOS tyrosine phosphorylation (Fig. 2). Additional data showed that Src-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of iNOS occurred on residue Tyr1055 (Figs. 3 and 4). We, therefore, reasoned that phosphorylation of Tyr1055 by Src could serve to stabilize the iNOS half-life. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the steady-state iNOS level of the Y1055F iNOS mutant compared with wild-type iNOS, following their transfection in HEK293 cells. The Y1055F mutation reduced the steady-state level of iNOS protein (Fig. 5A), whereas its mRNA level was unaffected (Fig. S4). Reduced level of iNOS Y1055F mutant was further confirmed by reduced iNOS activity in cell lysates (Fig. 5B) and a lower level of NO production into culture media (Fig. 5C). Incubation of transfected cells with the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 restored to a large extent the iNOS Y1055F mutant level (Fig. 5D), suggesting that the reduction of the steady-state level was caused by enhanced proteasomal degradation of the mutant. To confirm this hypothesis directly, we conducted pulse-chase analysis to measure the iNOS Tyr1055 mutant half-life, compared with wild type, in HEK293 cells. The iNOS Y1055F mutant had a significantly shorter half-life than wild-type iNOS (Fig. 5E), suggesting that phosphorylation of Tyr1055 is important for iNOS stability.

FIGURE 5.

Y1055F mutation reduces iNOS steady-state level. HEK293 cells were transfected with a plasmid encoding cDNA of wild-type (WT) iNOS or the iNOS Y1055F mutant. A, 24 h after transfection, cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting using iNOS or β-actin antibodies. B and C, iNOS activity was evaluated in cell lysates (B) and by measuring nitrite accumulation in culture media (C). D, 24 h after transfection, the proteasomal inhibitor MG132 (10 μm) or its vehicle (dimethyl sulfoxide) was added to cells for 18 h. E, 24 h after transfection, cells were pulsed with [35S]methionine/cysteine for 1 h and chased with unlabeled media at various time points. iNOS was immunoprecipitated with anti-iNOS antibody. Eluted proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Bands, representing 35S-labeled iNOS, were quantitated to calculate iNOS half-life. Data represent mean ± S.D. *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.001.

In a prior study on iNOS phosphorylation, residue Tyr151 of human iNOS was predicted as a possible site for Src-mediated phosphorylation (14). Our data above in Fig. 2B showed that iNOS mutant Y1055F is still slightly tyrosine-phosphorylated, albeit to a much less extent than wild type and suggesting that other phosphorylation sites might be operative. To investigate Tyr151 potential phosphorylation and function, we generated an iNOS Y151F mutant. In cells transfected with the iNOS Y151F mutant, tyrosine phosphorylation of iNOS was slightly reduced (Fig. S5A), suggesting that residue Tyr151 is also subject to phosphorylation, as predicted previously, albeit to a less extent than Tyr1055. Analysis of the Y151F iNOS mutant, however, did not show a significant difference in the iNOS steady-state level or NO production, compared with wild type (Fig. S5, B and C), suggesting that the iNOS Y151F mutant has stability similar to that of wild-type iNOS. These data indicate that Tyr151 phosphorylation does not affect iNOS stability. Altogether, our studies indicate that Tyr1055 is the major site for Src-mediated phosphorylation of iNOS, and its phosphorylation has a functional role in regulating iNOS stability.

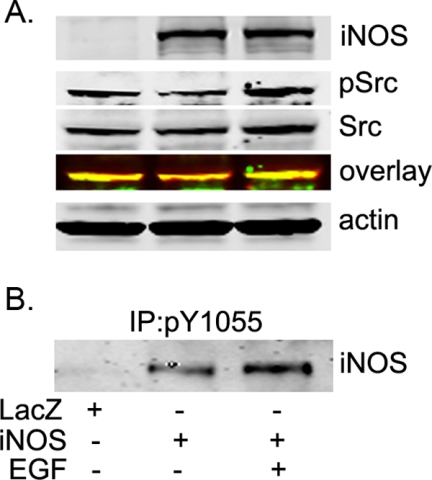

Activation of Src Kinase by EGF Enhances iNOS Tyr1055 Phosphorylation

c-Src has been functionally linked to EGFR. c-Src becomes transiently activated on association with activated EGFR and phosphorylates multiple downstream targets, including EGFR itself. In cancer cells that express high EGFR, inhibition of c-Src induces apoptosis. Thus, EGFR and c-Src interact bidirectionally and synergistically, and c-Src may be an important mediator of EGFR. Further, recent studies have shown that c-Src is activated in tumors from a subset of NSC lung cancer patients, contributes to the survival of EGFR-dependent NSC lung cancer cells, and thus represents a potential therapeutic targets in NSC lung cancer patients (2, 4). We, therefore, hypothesized that EGFR activation will lead to Src activation, which in turn will enhance iNOS Tyr1055 phosphorylation. To test this hypothesis, we treated iNOS-transfected HeLa cells with EGF and evaluated Src and iNOS. Activation of EGFR with EGF resulted in increased Src activation and a corresponding marked increase in iNOS Tyr1055 phosphorylation (Fig. 6). These data indicate that iNOS is a target for Src in the context of physiological stimulation of EGFR.

FIGURE 6.

Activation of Src kinase by EGF increases iNOS Tyr1055 phosphorylation. A, HeLa cells were transfected for 24 h with a plasmid encoding cDNA of human iNOS or LacZ, as a control. Cells were then incubated for 20 min in the presence or absence of 100 ng/ml EGF before lysis. Cell lysates were subjected to Western blotting using antibodies against iNOS, Src, p(416)Src, or β-actin. B, aliquots of cells lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) with pY1055 iNOS antibody. Immunoprecipitates were analyzed with Western blotting using iNOS antibody.

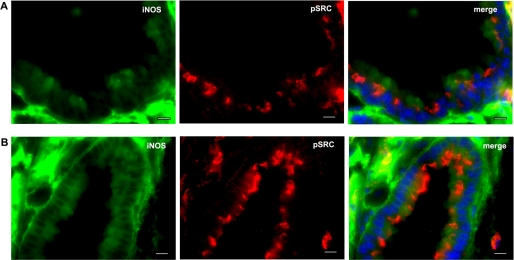

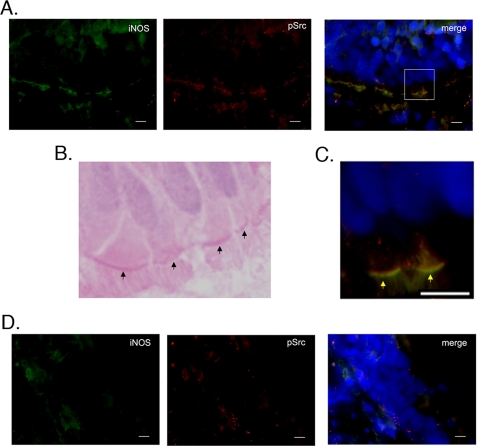

Co-localization of iNOS and Active Src in Airway Epithelium in a Mouse Model of Lung Inflammation and in Human NSC Lung Cancer Tissue

The above data showed that iNOS is a downstream target for Src. Both iNOS and Src have been implicated in inflammation and cancer. We, therefore, investigated the localization of both molecules in a model of lung inflammation induced by LPS and in human tissues of NSC lung cancer. Src activation is initiated by autophosphorylation of its Tyr416 residue, which is highly conserved among Src family members (23). We, therefore, used an antibody that detects Src phosphorylated on Tyr416 to determine localization of active Src (4). Mice were injected intraperitoneally with either phosphate-buffered saline (vehicle only) or LPS (1 mg/kg) for 18 h before they were killed. In LPS-injected mice, there was marked up-regulation of both iNOS and Src in the lung (Fig. 7). Further, LPS injection caused increased targeting of Src toward the apical side of airway epithelium. More importantly, both iNOS and Src co-localized, mostly in the airway epithelium. Analysis of human tissues of NSC lung cancer showed expression of both iNOS and active Src primarily in airway epithelium (Fig. 8). These data demonstrate spatial correlation between iNOS and Src in a model of lung inflammation and in NSC lung cancer.

FIGURE 7.

Co-localization of iNOS and active Src in airway epithelium of mouse lung tissue. Mice were intraperitoneally injected with either phosphate-buffered saline (vehicle only; A) or LPS (1 mg/kg; B) for 18 h before they were killed. Frozen sections of lung tissues were fixed and immunolabeled by anti-iNOS (mouse) and anti-p(416)Src (rabbit) antibodies followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (red), respectively. Cells were stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindol dihydrochloride (DAPI) to visualize nuclei (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm.

FIGURE 8.

Co-localization of iNOS and active Src in airway epithelium of NSC lung cancer tissue. A, frozen sections of NSC lung cancer tissue were fixed and immunolabeled by iNOS (mouse) and p(416)Src (rabbit) antibodies followed by goat anti-mouse IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 488 (green) and goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to Alexa Fluor 594 (red), respectively. Cells were stained with DAPI to visualize nuclei (blue). B, H&E staining of the tissue. Arrows denote apical part of the airway epithelial cells. C, higher magnification of section indicated by box in A. Arrows denote apical part of the airway epithelial cells. D, negative control. Tissues were evaluated as in A, except primary antibodies were omitted. Scale bars, 10 μm.

Lung airway (bronchial) epithelial cells are the principal cell type responsible for iNOS production in response to cytokines and inflammatory mediators in the pathogenesis of airway inflammation (7). In this study, the above data using mouse and human lung tissues suggested that the predominant site for both iNOS and activated Src was the airway epithelium. To confirm this finding directly, we extended our observations to a model of primary human bronchial epithelial cells cultured to full differentiation in an air-liquid interface. Using this model, primary cells differentiate to a heterogeneous population containing secretory, ciliated, and basal cells that mimic their in vivo appearance and function (16, 24). To mimic states of airway inflammation, primary cells were stimulated for 18 h by a mixture of proinflammatory cytokines, interferon-γ, interleukin-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α, and analyzed by immunofluorescence microscopy for iNOS and active Src expression. Under basal conditions, there was little expression of iNOS or active Src (Fig. S6A). However, following cytokine stimulation, there was marked up-regulation of both iNOS and active Src (Fig. S6B). These data reveal the co-expression of iNOS and active Src in primay airway cells and thus confirm the observations obtained the lung tissues above.

There are four main findings of our study. First, iNOS is a downstream target for phosphorylation by Src kinase. Second, the primary site for this phosphorylation is the highly conserved residue Tyr1055 of human iNOS. Third, an important function of Src-mediated phosphorylation is stabilization of iNOS half-life. Fourth, iNOS and active Src localize to airway epithelium in a model of lung inflammation and in NSC lung cancer tissues.

Our data clearly show that iNOS is regulated by Src kinase, in both normal cells and cancer cells. The Src family of kinases regulates many downstream targets with consequent activation of multiple signaling pathways controlling cellular growth, proliferation, apoptosis, cancer progression, and inflammation (3). Src activity is linked to EGFR activation in cancer such as in a subset of NSC lung cancer. In our study, Src activation and iNOS phosphorylation were enhanced following activation of EGFR. NO produced by iNOS is involved in diverse cellular process, similar to those described above for Src. Our study reveals that Src kinase, by regulating iNOS stability, can then modulate the cellular NO level. Thus, some of the biological actions for Src kinase could be mediated by NO. Further, some of the NO-induced actions can be modified by changes in the Src kinase level or state of activation.

Our study identifies the residue Tyr1055 in human iNOS as the major site for Src-mediated phosphorylation. This residue is at the reductase domain and lies near the C terminus of iNOS (25). It is a highly conserved residue among all NOSs and in various species. iNOS protein has three domains: (i) an N-terminal oxygenase domain (residues 1–504) that binds heme, tetrahydrobiopterin, and l-arginine and forms the active site where NO synthesis takes place; (ii) a C-terminal reductase domain (residues 537–1153) that binds FMN, FAD, and NADPH; and (iii) an intervening calmodulin-binding domain (residues 505–536) that regulates electron transfer between the oxygenase and reductase domains (6). During NO synthesis, the reductase flavins acquire electrons from NADPH and transfer them to the heme iron, which permits them to bind and activate O2 and catalyze NO synthesis. The residue Tyr1055 is present on one of the β-sheets of the NADPH-binding domain (25). Although our study revealed an important function of Tyr1055 phosphorylation in maintaining iNOS stability, it is conceivable that phosphorylation of Tyr1055 also modulates catalytic activity of iNOS by affecting NADPH binding or electron transfer through the reductase domain. Our data, however, showed that the reduction of iNOS activity and NO production in the iNOS Y1055F mutant could be accounted for by the reduction of iNOS protein level (Fig. 5). However, our model system utilizing iNOS in cultured cells does not allow for absolute quantitative analysis to determine iNOS activity per each molecule of iNOS. Such analysis would require experiments to be done using recombinant forms of iNOS and the iNOS mutant. iNOS is active only as a homodimer in which the subunits align in a head-to-head manner, with the oxygenase domains forming a dimer and the reductase domains existing as independent monomeric extensions (26). This active quaternary structure would thus allow access for Src kinase and subsequent phosphatase enzyme to iNOS phosphorylation residue on the reductase domain without disrupting the dimer interface or interfering with iNOS activity.

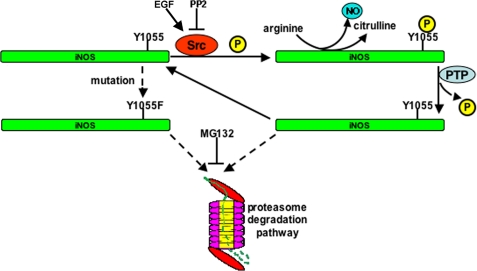

This study shows that an important function of Src-mediated phosphorylation is stabilization of iNOS half-life. It would then follow that dephosphorylation of iNOS by yet to be determined a tyrosine phosphatase would trigger iNOS degradation. We have shown previously that cells regulate iNOS activity by a rapid rate of degradation by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway (16, 19, 20) and by aggresome sequestration (17, 18, 27). Our studies using the iNOS Y1055F mutant indicated that this mutant is degraded faster than wild-type iNOS, and its rate of degradation can be almost normalized as wild-type, following proteasomal inhibition. Thus, the major pathway of accelerated iNOS degradation following its dephosphorylation is through the proteasome pathway. The proposed model of Src-mediated phosphorylation regulation of iNOS is shown in Fig. 9. Src interacts with and phosphorylates iNOS on Tyr1055 and thus stabilizes active iNOS. Dephosphorylation of Tyr1055 triggers targeting of iNOS for proteasomal degradation. These results are further illustrated in the iNOS Y1055F mutant, which is rapidly degraded by the proteasome.

FIGURE 9.

Proposed model of Src-mediated phosphorylation regulation of iNOS. Src interacts with and phosphorylates iNOS on Tyr1055 and thus stabilizes active iNOS. Dephosphorylation of Tyr1055 triggers targeting of iNOS for proteasomal degradation. These results are further illustrated in the iNOS Y1055F mutant, which is rapidly degraded by the proteasome. P, phosphate group; PTP, protein-tyrosine phosphatase.

Lung cancer is currently the most common cause of cancer-related death in the United States, with NSC lung cancer accounting for about 85% of all cases (2). Both Src kinase and iNOS have been previously implicated in several types of cancer, including NSC lung cancer. Specifically, it has been shown that the Src family of kinases is activated in NSC lung cancer and promotes the survival of EGFR-dependent cancer cell lines (4). Preclinical data suggest that Src inhibition is a viable therapeutic option in the treatment of advanced NSC lung cancer (2). Src offers a particularly promising molecular target for anti-NSC lung cancer therapy because inhibition of Src leads to inhibition of multiple signaling pathways implicated in cancer progression. Our study provides an additional dimension for these pathways by characterizing iNOS stabilization and hence enhancing NO production as a downstream consequence of Src activation. NO and iNOS have been implicated in various types of cancer in general and in NSC lung cancer in particular (10–12). The underlying mechanisms of involvement of NO and iNOS in cancer are related to NO effects in inflammation, angiogenesis, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. Our study shows functional interactions between Src and iNOS. These interactions require close spatial correlations. In a model of lung inflammation and in NSC lung cancer tissues, immunofluorescence studies localized both iNOS and Src to the same type of cells, mostly in airway epithelium. Because both iNOS and Src are up-regulated in cancer and inflammation in similar types of cells, it is likely that iNOS will prove to be a major effector of Src in cancer. The results of this study are important in understanding the mechanisms of actions of Src and how it regulates iNOS activity with important implications for understanding cancer biology and in designing anticancer therapeutic strategies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Wouter Moolenaar for Src-encoding plasmid, Dr. Li-Yuan Yu-Lee for useful discussions and critical review of the manuscript, and members of the Eissa laboratory for useful suggestions and discussions.

This work was supported by NHLBI and NIAID/National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental “Experimental Procedures” and Figs. S1–S6.

- NSC

- non-small cell

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- EGFR

- EGF receptor

- NO

- nitric oxide

- iNOS

- inducible nitric-oxide synthase

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- NHBE

- normal human bronchial epithelial

- o-van

- orthovanadate

- PP2

- 4-amino-5-(4-chlorophenyl)-7-(t-butyl)pyrazolo[3,4-d] pyrimidine

- PV

- pervanadate

- pY

- phosphotyrosine.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ishizawar R., Parsons S. J. (2004) Cancer Cell 6, 209–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giaccone G., Zucali P. A. (2008) Ann. Oncol. 19, 1219–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Page T. H., Smolinska M., Gillespie J., Urbaniak A. M., Foxwell B. M. (2009) Curr. Mol. Med. 9, 69–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang J., Kalyankrishna S., Wislez M., Thilaganathan N., Saigal B., Wei W., Ma L., Wistuba I. I., Johnson F. M., Kurie J. M. (2007) Am. J. Pathol. 170, 366–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ignarro L. J., Buga G. M., Wood K. S., Byrns R. E., Chaudhuri G. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 9265–9269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuehr D. J. (1999) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1411, 217–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guo F. H., Comhair S. A., Zheng S., Dweik R. A., Eissa N. T., Thomassen M. J., Calhoun W., Erzurum S. C. (2000) J. Immunol. 164, 5970–5980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie Q. W., Cho H. J., Calaycay J., Mumford R. A., Swiderek K. M., Lee T. D., Ding A., Troso T., Nathan C. (1992) Science 256, 225–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nathan C. (1997) J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2417–2423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen G. G., Lee T. W., Xu H., Yip J. H., Li M., Mok T. S., Yim A. P. (2008) Cancer 112, 372–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grimm E. A., Ellerhorst J., Tang C. H., Ekmekcioglu S. (2008) Nitric Oxide 19, 133–137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lala P. K., Chakraborty C. (2001) Lancet Oncol. 2, 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulton D., Church J. E., Ruan L., Li C., Sood S. G., Kemp B. E., Jennings I. G., Venema R. C. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 35943–35952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hausel P., Latado H., Courjault-Gautier F., Felley-Bosco E. (2006) Oncogene 25, 198–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan J., Burgher K. L., Szczepanik A. M., Ringheim G. E. (1996) Biochem. J. 314, 889–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolodziejski P. J., Koo J.-S., Eissa N. T. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 18141–18146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pandit L., Kolodziejska K. E., Zeng S., Eissa N. T. (2009) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1211–1215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolodziejska K. E., Burns A. R., Moore R. H., Stenoien D. L., Eissa N. T. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4854–4859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kolodziejski P. J., Musial A., Koo J.-S., Eissa N. T. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12315–12320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Musial A., Eissa N. T. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24268–24273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huyer G., Liu S., Kelly J., Moffat J., Payette P., Kennedy B., Tsaprailis G., Gresser M. J., Ramachandran C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 843–851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanke J. H., Gardner J. P., Dow R. L., Changelian P. S., Brissette W. H., Weringer E. J., Pollok B. A., Connelly P. A. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 695–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Johnson L. N., Noble M. E., Owen D. J. (1996) Cell 85, 149–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adler K. B., Li Y. (2001) Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 25, 397–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Garcin E. D., Bruns C. M., Lloyd S. J., Hosfield D. J., Tiso M., Gachhui R., Stuehr D. J., Tainer J. A., Getzoff E. D. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37918–37927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghosh D. K., Stuehr D. J. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 801–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sha Y., Pandit L., Zeng S., Eissa N. T. (2009) Mol. Cell. Biol. 29, 116–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.