Abstract

Paired box (Pax) proteins 3 and 7 are key determinants for embryonic skeletal muscle development by initiating myogenic regulatory factor (MRF) gene expression. We show that Pax3 and 7 participate in adult skeletal muscle plasticity during the initial responses to chronic overload (≤7 days) and appear to coordinate MyoD expression, a member of the MRF family of genes. Pax3 and 7 mRNA were higher than control within 12 h after initiation of overload, preceded the increase in MyoD mRNA on day 1, and peaked on day 2. On days 3 and 7, Pax7 mRNA remained higher than control, suggesting that satellite cell self-renewal was occurring. Pax3 and 7 and MyoD protein levels were higher than control on days 2 and 3. These data indicate that Pax3 and 7 coordinate the recapitulation of developmental-like regulatory mechanisms in response to growth-inducing stimuli in adult skeletal muscle, presumably through activation of satellite cells.

Keywords: plantaris, functional overload, satellite cell, muscle regulatory factor

Skeletal muscle hypertrophy is regulated, in part, by the expression of a number of myogenic genes that coordinate the process of myofiber growth. The myogenic regulatory factor (MRF) family of genes (MyoD, myf5, myogenin, and MRF4) direct the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of satellite cells that are required for augmenting the myonuclear number and, consequently, cellular volume of a muscle fiber.14 Some studies have shown that MRF expression is elevated early (within 1–2 days) and transiently with the onset of muscle overload,1,17 although others have reported that this response can be sustained for days10 or even weeks2,14 as the hypertrophy response continues. It is likely that the degree and temporal pattern of MRF expression is influenced by muscle phenotype, animal species, and the experimental conditions used to induce hypertrophy. Regardless, it is generally thought that the MRF increase in hypertrophying skeletal muscle is closely related to the activity of satellite cells or other interstitial muscle precursor cells.5,10,25 Among the MRFs, MyoD expression appears to be instrumental in the activation and proliferation of satellite cells as well as interstitial muscle precursor cells.1,10,25

There is recent evidence that paired box (Pax) proteins 3 and 7 are upstream transcription factors for the MRF genes and are instrumental in committing developmental somites into the myogenic lineage during embryogenesis6 by inducing the expression of MyoD.20,24 In prenatal and adult skeletal muscle, Pax7 and, in most muscles, Pax3 are putatively expressed at low levels in quiescent satellite cells.6 Kuang et al.11 showed that Pax3 and 7 were required for postnatal muscle growth and regeneration from injury: Pax7 expression was necessary for committing muscle presatellite cells into functional satellite cells, whereas Pax3 was identified in myogenic progenitor cells located in interstitial spaces and often was coexpressed with MyoD. Additionally, Zammit et al.28 showed that some activated satellite cells maintain high levels of Pax7, which suppresses differentiation and allows for the self-renewal of the satellite cells. Maintaining the satellite cell population ensures that skeletal muscle can sustain multiple bouts of injury, repair, and overload stimuli throughout the lifespan of the organism.

Investigations conducted to date on the roles of Pax3 and 7 in skeletal muscle have focused largely on in vitro and developmental models, whereas their potential role(s) in adult skeletal muscle has been limited to repair and regeneration paradigms, e.g., in response to chemical-induced (cardiotoxin) injury.11,16 The expression profile of MRF transcripts and proteins in hypertrophying adult rodent muscle has been well documented,1,2,10,14,15,17 but whether, and the degree to which, Pax3 and/or Pax7 participate in this process is unclear. The present study examined the time course of expression of Pax3, Pax7, and MyoD during the early phase (≤7 days) of mechanical overload of the rat plantaris muscle. We chose to examine MyoD in parallel with Pax3 and 7 because previous findings have shown that the expression of this MRF is regulated by Pax3, whereas myf5, MRF4, and myogenin are not.20,24 The experimental model of functional overload (FO) was chosen because it represents (1) a more general muscular adaptation to external stimuli than chemical injection, (2) skeletal muscle plasticity in a nondevelopmental scenario, and (3) an additional animal model other than those employed previously (e.g., mouse). Considering that Pax3 and Pax7 are constitutively expressed at low levels in adult skeletal muscle, we hypothesized that Pax3 and Pax7 mRNA and protein levels would be significantly increased in response to chronic overload and that their expression would increase earlier or in parallel with MyoD. We expected this response would be due, in part, to the increased activation and proliferation of satellite cells that accompany muscle overload and subsequent hypertrophy. These data show that Pax3 and 7 mRNA expression increases as early as 12 h following the initiation of muscle overload, occurs prior to a significant elevation in MyoD mRNA, and peaks after 3 days of overload. As overload continued, Pax3, Pax7, and MyoD protein levels followed a similar time course and peaked on days 2 and 3.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Surgical Procedures

The experimental and animal care procedures described here were approved by the University of California, Los Angeles Animal Research Committee, and followed the guidelines of the American Physiological Society. Adult female Sprague–Dawley rats (≈227 ± 4 g) were assigned randomly to one of seven groups: control timepoints at 0 (n = 7) and 7 (n = 4/timepoint) days; experimental groups consisting of timepoints at 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 7 days (n = 5/timepoint). Rapid plantaris muscle overload and hypertrophy was induced in experimental rats using the bilateral FO model whereby the gastrocnemius muscle was surgically removed.3 At each predetermined timepoint, selected rats were euthanized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg/kg). The plantaris muscle was removed bilaterally, trimmed of excess fat and connective tissue, wet weighed, frozen in isopentane cooled by liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until further analysis. The mRNA and protein analyses were performed on muscles from the right leg.

mRNA Analyses

Muscle samples (50–60 mg) were homogenized in 1 ml of TRI Reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, Ohio) and RNA was extracted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. RNA concentration was determined with a spectrophotometer and stored at −80°C for subsequent reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR was used to determine the expression of MyoD, Pax 3 or Pax 7 and β-actin mRNA and expressed relative to β-actin mRNA. One µg of total RNA from each muscle sample was reverse-transcribed using the Stratascript first strand synthesis system (Stratagene, La Jolla, California) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

For gene expression analysis, 1 µl of the reverse transcription reaction was added to a reaction mix containing 1× Full velocity SYBR Green (Stratagene) and 150 nM of either the MyoD, Pax 3, and Pax 7 or β-actin primer pairs. Amplification and quantitation of mRNA were performed on a Stratagene Mx3000P thermocycler with the following parameters: a denaturing step at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 10 s at 95°C and 30 s at 60°C for 40 cycles. The primer sequences (Operon, Technologies, Alameda, California) were as follows: MyoD: forward 5′-cgactgcctgtccagcatag-3′, reverse 5′ggacactgaggggtggagtc-3′; Pax 3: forward 5′-cagcccacgtctattccaca-3′, reverse 5′-cacgaagctgtcggtgtagc-3′; Pax 7: forward 5′-agccgagtgctcagaatcaa-3′, reverse 5′-tcctctcgaaagccttctcc-3′; β-actin: forward 5′-tggagaagatttggcacca-3′, reverse 5′-ccagaggcatacagggacaa-3′. PCR-generated fragments for these primer sets were 174, 168, 247, and 193 bp, respectively. All primer pairs produced a dilution curve of cDNA with a slope of 100 ± 10% “efficiency” where 100% =Δ3 Ct/log cDNA input (Ct is the threshold PCR cycle at which fluorescence is detected above baseline). Fluorescence measurements were taken at the end of each cycle (product extension period). After amplification, a melting curve analysis was performed to verify amplification product specificity. In initial experiments, PCR products were separated on 2% agarose gels, stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV light to validate that the PCR products were the appropriate size and no artifact bands were present. Additional controls included the elimination of Stratascript RT enzyme during cDNA synthesis (demonstrating the absence of DNA contamination) and the elimination of cDNA during PCR to demonstrate no contaminants in the PCR master mix. All PCR reactions were performed in duplicate for each reverse transcription product. The relative expression levels of Pax3, Pax7, or MyoD were normalized by subtracting the corresponding β-actin threshold cycle (CT) values and using the ΔΔCT comparative method.22

Protein Isolation and Western Analyses

Total muscle protein was isolated by rapid homogenization of preweighed frozen samples in 10 volume ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.8), 2 mM potassium phosphate, 2 mM EDTA, 2 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 3 mM benzamidine, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM leupeptin, 5 mg/ml aprotinin, and 1 mM 4-[(2-aminoethyl) benzenesulfonyl fluoride]. After homogenization the samples were centrifuged for 30 min at 13,000g and the supernatant was transferred to clean microcentrifuge tubes. Total protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad Protein Assay (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California) from a small aliquot of supernatant; the remainder of each sample was stored at −80°C until Western analysis. Loading for immunoblotting was determined to be 50 µg/sample for Pax3 and 7, and 100 µg/sample for MyoD, respectively. Two controls were run simultaneously with each gel: a biotin-conjugated molecular weight marker (Cell Signaling, Beverly, Massachusetts) and total protein isolated from neonatal (P8) rat muscle. Protein was denatured by boiling in SDS-PAGE sample buffer (0.2% SDS, 20% glycerol, 25% 4× buffer, 5% β-mercaptoethanol, and 0.025% bromophenol blue) for 2 min and electrophoresed in an SDS-10% polyacrylamide gel at 80 V for 20 min and then 140 V for 60 min. The proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes for 3 h at 500 mA. Following transfer the membranes were placed in a solution of Ponceau Red (Sigma, St. Louis, Missouri) to verify equal loading among samples (data not shown) and then immersed in a blocking solution containing 5% nonfat dry milk (Bio-Rad) dissolved in Tris-buffered saline with 0.05% Tween-20 (T-TBS) for 1 h. The membranes were incubated in either mouse anti-Pax3 (1:1,000) (Hybridoma Bank, Iowa City, Iowa), anti-Pax7 (1:1,000) (Hybridoma Bank) or anti-MyoD (1:400) (Dako, Carpinteria, California) diluted in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. The membranes were washed 6 × 10 min in T-TBS and incubated for 1 h in a secondary antibody cocktail (anti-biotin, 1:5,000; goat anti-mouse IgG, 1:3,000) at room temperature. The membranes were developed using an ECL detection kit (Amersham, Piscataway, New Jersey) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Densitometry and quantification were performed using ImageJ software.19 The presence of multiple bands for Pax3 and 7 have previously been reported.26 For quantitative purposes, a single densitometric number was generated for each sample and used for statistical comparison. Arbitrary units generated for background density were first subtracted from the density levels of Pax3, Pax7, and MyoD before statistical analyses.

Statistical Analysis

All data are reported as mean ± SEM. The mRNA and protein levels between the control tissues at days 0 and 7 were similar (P > 0.05); thus, these data were pooled as a single control group. Within-group-time and between-group comparisons were performed using a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey’s post-hoc analyses. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Body and Muscle Masses

Body and plantaris muscle masses during the course of the study have been reported previously by Huey et al.9 Mean absolute plantaris mass was 21% and mean relative mass 15% greater in FO than Con (control) rats on day 7.

Pax3, Pax7, and MyoD mRNA Levels

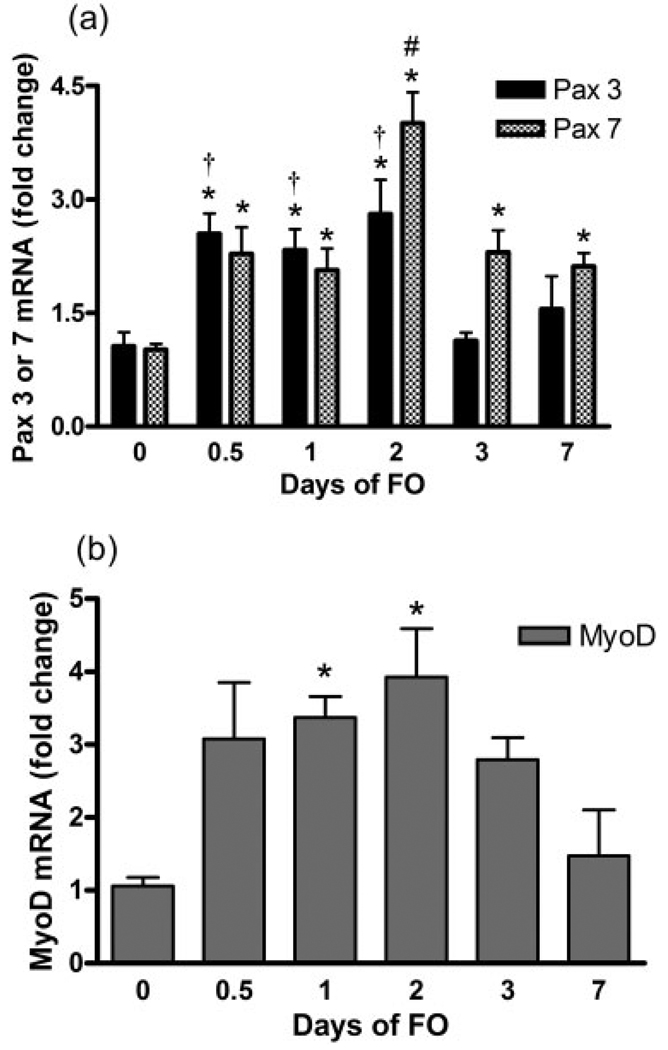

Within 12 h of FO, the Pax3 and Pax7 mRNA levels were higher (>2-fold) in the FO than Con plantaris muscles (Fig. 1a). Both gene transcripts remained higher than Con at 1 and 2 days of FO and peaked (>3-fold) at 2 days. On days 3 and 7, Pax3 mRNA had returned to basal levels, whereas Pax7 mRNA remained elevated (≈2-fold) relative to the Con group. MyoD mRNA (Fig. 1b) was higher (3–4-fold) in the FO than Congroup at 1 and 2 days and similar to Con at all other timepoints.

FIGURE 1.

Average fold changes in Pax3 and Pax7 (a) and MyoD (b) mRNA as assessed by RT-PCR after 0 (Control), 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 7 days of functional overload (FO) of the plantaris muscle. Values are mean ± SEM. *, †, #: significantly different from control (day 0), day 3, or all other days of FO, respectively, at P < 0.05.

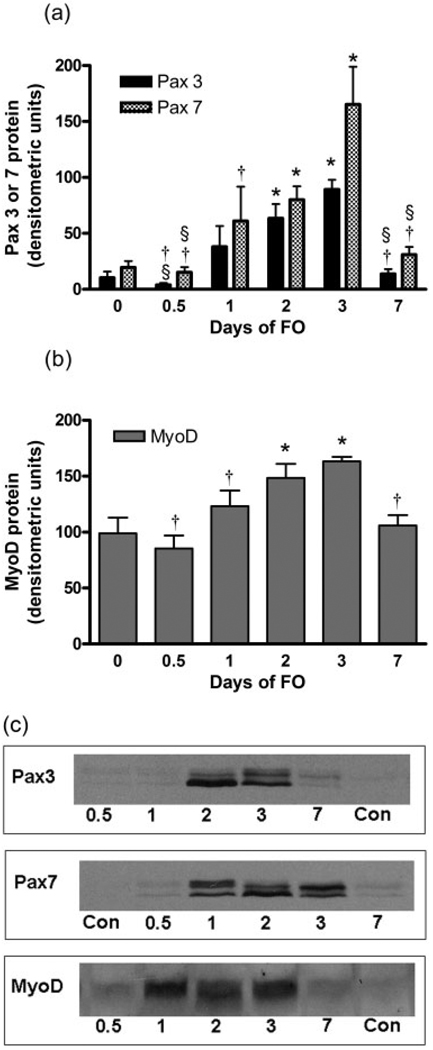

Pax3, Pax7, and MyoD Protein Levels

In general, there was a progressive increase in Pax3 and Pax7 (Fig. 2a), and in MyoD (Fig. 2b) proteins in FO plantaris muscles beginning on day 1 and peaking on day 3. The levels of Pax3, Pax7, and MyoD were higher than Con on days 2 and 3; by day 7 the Pax3, Pax7, and MyoD protein levels had returned to Con levels. These changes are reflected in the representative Western blots (Fig. 2c) Pax3 and Pax7 protein bands appeared as doublets as previously observed25 and were quantified as a single band for group comparisons.

FIGURE 2.

Average changes in Pax3 (a) or Pax7 (b) and MyoD proteins as assessed by Western blot analysis after 0 (Control), 0.5, 1, 2, 3, and 7 days of functional overload (FO) of the plantaris muscle. Representative Western blots for Pax3, Pax7, and MyoD proteins are shown (c); Pax3 and Pax7 proteins occurred as doublets as previously reported by Vorobyov and Horst.26 Values are mean ± SEM. *, †, §: significantly different from control, day 3, or day 2 of FO, respectively, at P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to show that Pax3 and Pax7 mRNAs rapidly increase in response to overload of an adult rat skeletal muscle and that these increases precede any change in MyoD expression. This time course is consistent with previous findings from developmental studies indicating that Pax3 and 7 coordinate the expression of MRFs.20 It is likely that the increases in Pax3 and 7 are the result of newly activated satellite cells or interstitial muscle precursor cells inasmuch as earlier work has attributed the rise in MyoD during the initial stages of hypertrophy to an increased activation and/or proliferation of these cells.5

Although both Pax 3 and 7 mRNA levels were higher than Con from 12 h to 2 days of FO, only Pax7 mRNA was higher than Con at days 3 and 7 of FO. These data support the notion that Pax7 is necessary for satellite cell self-renewal in adult muscle during the early stages of overload leading to hypertrophy.13,20,28 Pax7 protein levels returned to Con values on FO day 7, while Pax7 mRNA remained elevated above Con levels, suggesting possible alterations in translation and or protein degradation. Similar discordant expression levels of mRNA and protein during compensatory growth periods18 have been observed previously. For example, Beauchamp et al.4 reported that a large number (≈80%) of satellite cells express Myf5 transcripts despite no detectable protein product in prenatal muscle, indicating that the MRF mRNA is not necessarily translated into protein. It is possible that Pax7 gene transcription persists and that posttranscriptional regulation fine-tunes the necessity for translation to ensure that satellite cell self-renewal occurs and may explain the elevated Pax7 mRNA, but not protein, observed on FO day 7.

Satellite cells putatively express Pax7 and, in some mammalian muscles such as the diaphragm, Pax3 genes. Montarras et al.13 showed that while 47% of the mononuclear cells isolated by flow cytometry from mouse diaphragm were satellite cells (Pax3+/CD34+) only 0.25% of the cells isolated from lower hindleg muscles were colabeled for Pax3 and CD34. This suggests that quiescent satellite cells from adult locomotor muscles may not express Pax3. Our analyses, however, detected both Pax3 and Pax7 mRNA and protein in plantaris muscles of Con and FO rats (Fig. 1, Fig. 2), although these proteins were at very low levels in the samples from Con rats. At present, we have not definitively localized the cellular source due to technical limitations when using Pax3 and 7 antibodies for immunohistochemistry in adult rat tissues. We speculate that the Pax3 and Pax7 antibodies recognize these proteins in a denatured state (e.g., Western blots) but not in their folded conformation in rat skeletal muscle cross-sections. Successful Pax3 and Pax7 immunohistochemical analyses performed in mouse11 and chicken8 muscle also suggest a species-specific reactivity. However, of the few muscle cross-sections appearing to show a positive reactivity to Pax3 antibodies in the present study, labeled nuclei were positioned adjacent to muscle fibers, which is anatomically consistent with satellite cells (data not shown). An alternative possibility is the migration of interstitial muscle progenitor cells to a position adjacent to the fiber where they could contribute to the increases in Pax3 protein found with Western analyses (Fig. 2). Clearly, development of an immunohistochemical protocol that is consistently successful in recognizing Pax3 and 7 proteins in adult rat skeletal muscle cross-sections is necessary.

To our knowledge, this is the first study reporting Pax3 and Pax7 expression in a lower hindlimb muscle of adult rats; thus, there may be differences in rodent species that account for the differences observed here and in the mice reported by others.13,20 Specifically, our analyses utilized the rat plantaris muscle, whereas Montarras et al.13 conducted their experiments on what appears to be a combination of several or all of the lower hindleg muscles in mice. It is possible, therefore, that different muscles of the lower hindleg have variable expression of Pax3, which may suggest a muscle phenotype and/or functionally specific expression among skeletal muscles. Lastly, although we detected small amounts of mRNA and protein expression in Con (non-FO) rats, the greatest levels of Pax3 and Pax7 were observed in FO rats on days 2 and 3. This suggests that experimental manipulation favoring the expression of these proteins (e.g., chronic muscle overload that induces hypertrophy) was necessary to induce gene expression above that observed in the muscles of Con rats.

The observed time course of adaptation in MyoD mRNA and protein levels after FO is similar to that reported previously.1,10,17 No significant changes in plantaris muscle mass were observed until FO day 7,9 indicating that the earlier rise in MyoD, Pax3, and Pax7 signaled intramuscular events leading to hypertrophy prior to an actual increase in muscle mass. Acute increases in MyoD, Pax3, and Pax7 content also have been observed following chemical injection of cardiotoxin to induce skeletal muscle degeneration and subsequent regeneration in mice.7,11 Both chronic overload and chemical agents induce muscular damage but the degree of injury is drastically different. Cardiotoxin injection induces massive myofibrillar degeneration in which fibers are presumably destroyed and subsequently regenerated by the satellite cells that are unaffected by chemical treatment.27 This scenario is, arguably, physiologically rare and contrasts with more typical alterations in muscle activation and loading. FO muscles appear morphologically similar to those in Con rats, and contain only “occasional” necrotic fibers23 or focal disruptions at the level of the sarcomeres (e.g., Z-line streaming).21,23

The upregulation of Pax3 and 7 in the plantaris of FO rats observed in the present study suggests that these transcription factors participate in the muscle plasticity associated with chronic overload. Pax3 and 7 are muscle-specific proteins and, to date, have not been shown to be expressed in muscle fiber nuclei. The acute upregulation of Pax3 and 7 in FO muscles coincides with the time frame known to induce activation and proliferation of satellite cells.10 Thus, we surmise that the higher levels of Pax3 and Pax7 in the plantaris of FO than Con rats reflect the mobilization of satellite cells or interstitial muscle precursor cells. Our data support the view that satellite cell activation, proliferation, and fusion are required for hypertrophy, which has been the topic of recent debates.12,15 Furthermore, these data indicate that adult skeletal muscle can recapitulate developmental-like responses to adapt to growth-inducing stimuli.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH R03AR049855 to KAH and NIH NS16333, Project 1 to RRR.

Abbreviations

- FO

functional overload

- MRF

myogenic regulatory factor

- Pax

paired box

- RT-PCR

reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams GR, Haddad F, Baldwin KM. Time course of changes in markers of myogenesis in overloaded rat skeletal muscles. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87:1705–1712. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.5.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alway SE, Degens H, Krishnamurthy G, Smith CA. Potential role for Id myogenic repressors in apoptosis and attenuation of hypertrophy in muscles of aged rats. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;283:C66–C76. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00598.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baldwin KM, Valdez V, Herrick RE, MacIntosh AM, Roy RR. Biochemical properties of overloaded fast-twitch skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol. 1982;52:467–472. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1982.52.2.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beauchamp JR, Heslop L, Yu DS, Tajbakhsh S, Kelly RG, Wernig A et al. Expression of CD34 and Myf5 defines the majority of quiescent adult skeletal muscle satellite cells. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1221–1234. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bornemann A, Maier F, Kuschel R. Satellite cells as players and targets in normal and diseased muscle. Neuropediatrics. 1999;30:167–175. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-973486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buckingham M, Relaix F. The role of Pax genes in the development of tissues and organs: Pax3 and Pax7 regulate muscle progenitor cell functions. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:645–673. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper RN, Tajbakhsh S, Mouly V, Cossu G, Buckingham M, Butler-Browne GS. In vivo satellite cell activation via Myf5 and MyoD in regenerating mouse skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci. 1999;112:2895–2901. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.17.2895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Halevy O, Piestun Y, Allouh MZ, Rosser BW, Rinkevich Y, Reshef R et al. Pattern of Pax7 expression during myogenesis in the posthatch chicken establishes a model for satellite cell differentiation and renewal. Dev Dyn. 2004;23:489–502. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huey KA, McCall GE, Zhong H, Roy RR. Modulation of HSP25 and TNF-a during the early stages of functional overload of a rat slow and fast muscle. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102:2307–2314. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00021.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ishido M, Kami K, Masuhara M. Localization of MyoD, myogenin and cell cycle regulatory factors in hypertrophying rat skeletal muscles. Acta Physiol Scand. 2004;180:281–289. doi: 10.1046/j.0001-6772.2003.01238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuang S, Chargé SB, Seale P, Huh M, Rudnicki MA. Distinct roles for Pax7 and Pax3 in adult regenerative myogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:103–113. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy JJ, Esser KA. Counterpoint: satellite cell addition is not obligatory for skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1100–1102. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00101.2007a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Montarras D, Morgan J, Collins C, Relaix F, Zaffran S, Cumano S et al. Direct isolation of satellite cells for skeletal muscle regeneration. Science. 2005;309:2064–2067. doi: 10.1126/science.1114758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mozdziak PE, Greaser ML, Schultz E. Myogenin, MyoD, and myosin expression after pharmacologically and surgically induced hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 1998;84:1359–1364. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1998.84.4.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Connor RS, Pavlath GK. Point: counterpoint: satellite cell addition is/is not obligatory for skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2007;103:1099–1100. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00101.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oustanina S, Hause G, Braun T. Pax7 directs postnatal renewal and propagation of myogenic satellite cells but not their specification. EMBO J. 2004;23:3430–3439. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Owino V, Yang SY, Goldspink G. Age-related loss of skeletal muscle function and the inability to express the autocrine form of insulin-like growth factor-1 (MGF) in response to mechanical overload. FEBS Lett. 2001;505:259–263. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02825-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Picha ME, Silverstein JT, Borski RJ. Discordant regulation of hepatic IGF-I mRNA and circulating IGF-I during compensatory growth in a teleost, the hybrid striped bass (Morone chrysopsx Morone saxatilis) . Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2006;147:196–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasband WS. U. S. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland, USA: ImageJ. 1997–2007 http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/

- 20.Relaix F, Montarras D, Zaffran S, Gayraud-Morel B, Rocancourt D, Tajbakhsh S et al. Pax3 and Pax7 have distinct and overlapping functions in adult muscle progenitor cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:91–102. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schiaffino S, Bormioli SP, Aloisi M. The fate of newly formed satellite cells during compensatory muscle hypertrophy. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol. 1976;21:113–118. doi: 10.1007/BF02899148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmittgen TD, Zakrajsek BA, Mills AG, Gorn V, Singer MJ, Reed MW. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction to study mRNA decay: comparison of endpoint and real-time methods. Anal Biochem. 2000;28:194–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snow M. Satellite cell response in rat soleus muscle undergoing hypertrophy due to surgical ablation of synergists. Anat Rec. 1990;227:437–446. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092270407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tajbakhsh S, Rocancourt D, Cossu G, Buckingham M. Redefining the genetic hierarchies controlling skeletal myogenesis: Pax-3 and Myf-5 act upstream of MyoD. Cell. 1997;89:127–138. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tamaki T, Akatsuka A, Ando K, Nakamura Y, Matsuzawa H, Hotta T et al. Identification of myogenic-endothelial progenitor cells in the interstitial spaces of skeletal muscle. J Cell Biol. 2002;157:571–577. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200112106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vorobyov E, Horst J. Expression of two protein isoforms of PAX7 is controlled by competing cleavage-polyadenylation and splicing. Gene. 2004;342:107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yan Z, Choi S, Liu X, Zhang M, Schageman JJ, Lee SY et al. Highly coordinated gene regulation in mouse skeletal muscle regeneration. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8826–8836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zammit PS, Golding JP, Nagata Y, Hudon V, Partridge TA, Beauchamp JR. Muscle satellite cells adopt divergent fates: a mechanism for self-renewal? J Cell Biol. 2004;166:347–357. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]