Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) is important in inflammation, angiogenesis, reepithelialization and connective tissue regeneration during wound healing. We analyzed components of TGFβ signaling pathway in biopsies from 10 patients with nonhealing venous ulcers (VUs). Using comparative genomics of transcriptional profiles of VUs and TGFβ-treated keratinocytes, we found deregulation of TGFβ target genes in VUs. Using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and immunohistochemical analysis, we found suppression of TGFβ RI, TGFβ RII and TGFβ RIII, and complete absence of phosphorylated Smad2 (pSmad2) in VU epidermis. In contrast, pSmad2 was induced in the cells of the migrating epithelial tongue of acute wounds. TGFβ-inducible transcription factors (GADD45β , ATF3 and ZFP36L1) were suppressed in VUs. Likewise, genes suppressed by TGFβ (FABP5, CSTA and S100A8) were induced in nonhealing VUs. An inhibitor of Smad signaling, Smad7 was also downregulated in VUs. We conclude that TGFβ signaling is functionally blocked in VUs by downregulation of TGFβ receptors and attenuation of Smad signaling resulting in deregulation of TGFβ target genes and consequent hyperproliferation. These data suggest that application of exogenous TGFβ may not be a beneficial treatment for VUs.

INTRODUCTION

Chronic wounds, including venous ulcers, represent a challenging clinical problem. It is estimated that, in the US, each year more than 8 million patients develop chronic nonhealing wounds, including pressure, venous and diabetic ulcers and burns (1). Although venous and arterial insufficiencies are well-known etiological factors involved in the pathogenesis of chronic wounds, little is known about the molecular events leading to chronic wounds. We previously reported that keratinocytes at the nonhealing edges of chronic wounds do not properly execute activation or differentiation pathways, resulting in a thick, hyperproliferative, hyper- and parakeratotic epidermis (2). In addition, resident fibroblasts are senescent and unresponsive to growth factors (3–6). Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ ) is a pleiotropic cytokine that participates in maintenance of epidermal homeostasis. It is also known as growth-inhibitory cytokine, particularly in epithelial tissues (7). In addition, TGFβ coordinates the wound-healing response (8) and regulates reepithelialization, inflammation, granulation-tissue formation and wound contraction ((6,9–11)). TGFβ mediates its signaling by binding to TGFβ receptor II (TGFβ RII) followed by heterodimerization and phosphorylation of TGFβ receptor I (TGFβ RI) (12,13).

Activated TGFβ RII binds and phosphorylates receptor-activated Smad2 or Smad3, which heterodimerize with Smad4 (14,15). This complex translocates into the nucleus, binds to Smad-binding promoter elements and regulates expression of target genes. Members of the third group, inhibitory Smad6 and Smad7, are also induced by TGFβ . They prevent phosphorylation and/or nuclear translocation of receptor-associated Smads, acting as a negative feedback loop (16,17).

After acute injury, TGFβ 1 is rapidly up-regulated and secreted by keratinocytes, platelets, monocytes, fibroblasts and macrophages (18). Although TGFβ and its receptors are highly expressed in acute wounds, TGFβ 1 and TGFβ RII expression is reduced in chronic wounds (19–22). In addition, in vitro studies have revealed that VU-derived fibroblasts have reduced levels of the TGFβ RII (4) and are therefore unresponsive to TGFβ 1. Numerous studies have shown that exogenously applied TGFβ accelerates acute wound healing (23,24). Furthermore, application of recombinant TGFβ improves healing in animal models (25,26). However, despite these studies in animal models (23,27), treatment of human chronic ulcers with TGFβ has not met expectations, due to its limited effects (28,29).

To study the mechanism by which TGFβ signaling participates in the pathogenesis of VUs, we analyzed proteins of the TGFβ /Smad signaling cascade and target gene expression in biopsies derived from nonhealing edges of 10 patients with VUs. Using qPCR and immunohistochemistry, we found downregulation of TGFβ RI, TGFβ RII and TGFβ RIII as well as signaling molecules pSmad2 and Smad7 in the epidermis of nonhealing VUs. Comparative genomics and qPCR revealed that expression of TGFβ target genes in VUs is the opposite from that found in TGFβ-treated keratinocytes. Thus, in nonhealing VUs, TGFβ signaling is attenuated by downregulation of all three TGFβ receptors, failed activation of Smad2 and downregulation of Smad7 resulting in deregulation of TGFβ target genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Skin Specimens

Healthy skin specimens (n = 4) were obtained as discarded tissue from patients 46–72 years of age who were undergoing elective plastic surgery. Skin biopsies derived from nonhealing edges of VUs were collected from tissue normally discarded after surgical debridement procedures, per institutional review board–approved protocol. Patients (n = 10) were included after their consent for the use of their discarded skin samples was obtained and their diagnosis was confirmed (1). None of the patients had diabetes. Evaluation for ischemia was performed either by non-invasive flow exams (ankle-brachial index of <0.9) or arteriogram, and ischemia was ruled out in all patients. Patients were between 43 and 83 years of age. All patients underwent debridement in the operating room under monitored anesthesia care or general anesthesia, and local lidocaine injection was used for local anesthesia. The nonhealing wound edges used in this study were clinically identified by a surgeon as the most proximal skin edge to the ulcer bed. Skin biopsies were then processed as follows: samples were (a) embedded in OCT (optimal cutting temperature) compound (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA), (b) stored in formalin for paraffin embedding and (c) stored in RNAlater (Ambion/Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) for subsequent RNA isolation. Samples were standardized as previously described (2). Tissue morphology was evaluated using hematoxylin and eosin staining. All specimens showed characteristic hyperproliferative, hyper- and parakeratotic epidermis and the nuclear presence of β-catenin (30).

Human Skin ex vivo Wound-Healing Model

Healthy skin samples were used to generate acute wounds as previously described (30–33). Ex vivo human experimental wound models have been extensively used to study wound healing in human skin. Moreover, comparative analyses between ex vivo wound models and acute human wounds confirmed similar expression patterns for multiple genes involved in epithelilization and wound healing at both protein and mRNA levels (34–37), suggesting that this model is reliable and useful in studying human epidermal healing.

Under sterile conditions, subcutaneous fat was trimmed from skin before generating wounds. A 3-mm punch (Acuderm, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA) was used to make wounds in the epidermis through the reticular dermis, and 3-mm discs of epidermis were excised using sterile scissors. Skin discs (6 mm) with the 3-mm epidermal wound in the center were excised using a 6-mm biopsy punch (Acuderm). Specimens of wounded skin were immediately transferred to the air–liquid interface with DMEM (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, MD, USA) supplemented with antibiotics-antimycotics and fetal bovine serum (Gemimi Bio-Products, West Sacramento, CA, USA). The skin samples were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. Tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Immunohistochemistry

Frozen sections were used for staining with antibodies against TGFβ RI and TGFβ RII. (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Sections were fixed with acetone, rinsed in Tris-buffered saline (TBS) plus 0.025% Triton X-100, blocked in 1% bovine serum albumin in TBS and incubated with rabbit polyclonal anti-TGFβ RI (1:100) or rabbit anti-TGFβ RII (1:250) antibody overnight at 4°C. Samples were rinsed in TBS plus 0.025% Triton X-100 and incubated with the secondary antibody (Alexa-Flour) for 1 h and mounted with propidum iodide mounting medium (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA, USA). For detection of TGFβ RIII, paraffin sections were dewaxed and rehydrated. Antigens were retrieved by microwaving sections in citrate buffer. Endogenous peroxidase was blocked by incubation in 1% serum supplied by the Vectastain kit (Vector Labs). The primary antibody, rabbit anti-TGFβ RIII (1:100; LifeSpan Biosciences, Seattle, WA, USA) was applied at 4°C overnight. The secondary antibody was applied, and antigens were visualized by DAB (3, 3′-diaminobenzidine) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Vector Labs).

Paraffin sections were also used for staining with anti–phospho-Smad2 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and anti-Smad7 antibodies (LifeSpan Biosciences). Antigen retrieval was performed using Dako retrieval solution (Dako, Carpinteria, CA, USA), and endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched. Unspecific protein binding was blocked and antibodies were applied according to instructions in the Vectastain Universal Kit (Vector Labs). For visualization DAB (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) tablets were used. Samples were counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted. Specimens were analyzed with a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope. Digital images were collected using the SPOT Camera Advanced program.

Cell Culture

Normal human epidermal keratinocytes were initiated using 3T3 feeder layers for storage as described (38). The keratinocytes were grown, without feeder cells, in defined serum-free keratinocyte medium supplemented with epidermal growth factor and bovine pituitary extract (Keratinocyte-SFM; Gibco, Carls-bad, CA, USA) ((31,32,39)). Cells were expanded through two 1:4 passages and grown to 80% confluence after being washed with 1XPBS several times before incubation in basal keratinocyte medium (Gibco) that was custom made without phenol-red, hydrocortisone and thyroid hormone. Keratinocytes were incubated for 24 h in the presence or absence of 40 pmol/L recombinant human TGFβ 1 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Comparison of Gene-Array Data

We used the LOLA programs for comparing lists of genes (40,41). Lists of genes regulated in biopsies obtained from patients with chronic VUs (2) were compared with the list of genes regulated by TGFβ 1 treatment in primary human keratinocytes (Blumenberg M and Zavadil J, unpublished data).

RNA Isolation and qPCR Analysis

Tissue was homogenized and RNA isolation and purification was performed using an miRVana RNA isolation Kit (Ambion/Applied Biosystems).

For real-time qPCR, 0.5 μg of total RNA from healthy skin and chronic wounds was reverse transcribed using an Omniscript Reverse Transcription kit (Qiagen). Real-time PCR was performed in triplicates using the Opticon2 thermal cycler and detection system and an iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Relative expression was normalized for levels of HPRT1. The primer sequences used were:

HPRT1, forward (5′-AAAGGACCCC ACGAAGTGTT-3′ ) and reverse (5′-TCAAG GGCATATCCTACAACAA-3′ ); Smad7, forward (5′-ACTCCAGATACCCGATG-GATTT-3′ ) and reverse (5′-CCTCC CAGTATGCCACCAC-3′ ); TGFβ RI forward (5′-ACGGCGTTACAGTGTTTCTG-3′ ) and reverse (5′-GCACATACAAACGGC CTATCT-3′ ); TGFβ RII, forward (5′-CCAAG GGCAACCTACAGGAG-3′ ) and reverse (5′-GTGGAGGTGAGCAATCCCA-3′ ); TGFβ RIII forward (5′-ACCTGTCAGT GCCTCCCAT-3′ ) and reverse (5′-GAGCA GGAACACAACAGACTT-3′ ); Smad2 forward (5′-GCCATCACCACTCAA AACTGT-3′ ) and reverse (5′-GCCTG TTGTATCCCACTGATCTA-3′ ); Smad3 forward (5′-GAACGTCAACACCAA CTGCAT-3′ ) and reverse (5′-ACGCA GACCTCGTCCTTCT-3′ ); Smad4 forward (5′-ATGTGATCTATGCCCGTCTCT-3′ ) and reverse (5′-AGGTGATACAACTCG TTCGTAGT-3′ ); GADD45β forward (5′-ACAGTGGGGGTGTACGAGTC) and reverse (5′-ATGAGCGTGAAGTGG ATTTGC-3′ ); ATF3 forward (5′-TCGGG GTGTCCATCACAAAAG-3′ ) and reverse (5′-GGCCGATGAAGGTTGAGCA-3′ ); ZFP36L1 forward (5′-ACTCCAGCCG CTACAAGAC-3′ ) and reverse (5′-CGTAG GGGCAAAAGCCGAT-3′ ); S100A8 forward (5′-TGATAAAGGGGAATTTCCAT GCC-3′ ) and reverse (5′-ACACTCGGTC TCTAGCAATTTCT-3′ ); CSTA forward (5′-AACCCGCCACTCCAGAAATC-3′ ) and reverse (5′-CACCTGCTCGTACCT TAATGTAG-3′ ) and FABP5 forward (5′-ATGAAGGAGCTAGGAGTGGGA-3′ ) and reverse (5′-TGCACCATCTGTAAA GTTGCAG-3′ ). Statistical comparisons of expression levels from chronic wound versus healthy skin were performed using the Student t test. Statistically significant differences between VUs and healthy skin controls were defined as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

TGFβ Signaling Is Reduced in VUs

To analyze TGFβ signaling in the epidermis of the wound edge of VUs, we compared transcriptional profiles of biopsies obtained from VU patients (2) with profiles of primary human keratinocytes treated with TGFβ (Blumenberg M and Zavadil J, unpublished data) using the LOLA program ((32,40,42)). RNA isolated from VU biopsies predominantly originated from hyperproliferative epidermal keratinocytes, and the amount of dermal RNA was minimal according to expression of the mesenchymal tissue marker vimentin1 (data not shown). The genomic comparison identified an inverse correlation between the genes deregulated in VU and TGFβ-regulated genes. Specifically, 73 genes that are suppressed by TGFβ treatment were induced in VU (P = 1.43e−44), whereas 67 genes induced by TGFβ treatment were downregulated in VUs (P = 2.34e−30). These data suggest deregulation of TGFβ signaling in the nonhealing edge of VUs.

Expression of TGFβ Receptors Is Reduced in VUs

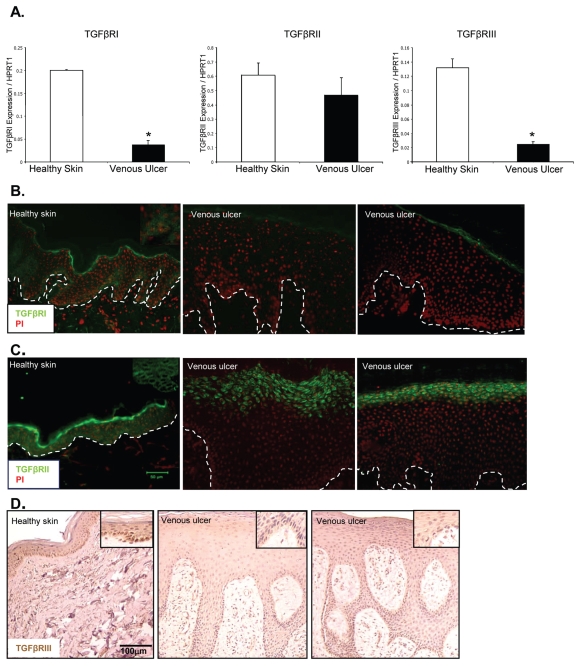

TGFβ plays a crucial role in overall maintenance of epidermal tissue homeostasis by delivering cytostatic signals (7), in contrast to the epidermis of the non-healing edge of VUs, which is hyperproliferative (2,30). Thus, to assess all the components of the TGFβ pathway in nonhealing VUs, we used patient biopsies from the nonhealing edge of VUs and normal skin tissue for comparison. We analyzed the mRNA levels of TGFβ RI, TGFβ RII and TGFβ RIII using qPCR. TGFβ RI and TGFβ RIII mRNA levels were reduced in nonhealing edges of VUs compared with steady-state levels of healthy skin. Expression levels of TGFβ RII were not significantly altered in VUs (Figure 1A). Interestingly, immunohistochemistry revealed dramatic down-regulation of both TGFβ RI and TGFβ RII in VUs compared with healthy skin (Figure 1B, C), suggesting that TGFβ RII suppression occurs on a posttranscriptional level. TGFβ RI was predominantly expressed in the basal layer of healthy skin, but was not detectable in any of the VUs. Similarly, TGFβ RII was expressed throughout the epidermis of healthy skin, whereas it was absent in basal and suprabasal layers of hyperproliferative VU epidermis. For TGFβ RIII, we detected downregulation on both the mRNA and protein level (Figure 1A, D).

Figure 1.

Deregulation of TGFβ RI, TGFβ RII and TGFβ RIII in VUs. (A) Expression levels of TGFβ RI, TGFβ RII and TGFβ RIII by qPCR. Mean values are represented after normalization to the expression level of HPRT1. Error bars indicate mean ± SD. *Statistically significant differences between VUs and healthy skin were defined as P < 0.05 (A). Immunofluorescence microscopy of healthy skin shows TGFβ RI staining in the basal layer of epidermis. TGFβ RI is absent in VUs (B). TGFβ RII is expressed throughout the epidermis of healthy skin, but not in VUs (C). TGFβ RIII is downregulated in VUs (D).

TGFβ Signaling via Smads Is Attenuated in Venous Ulcers

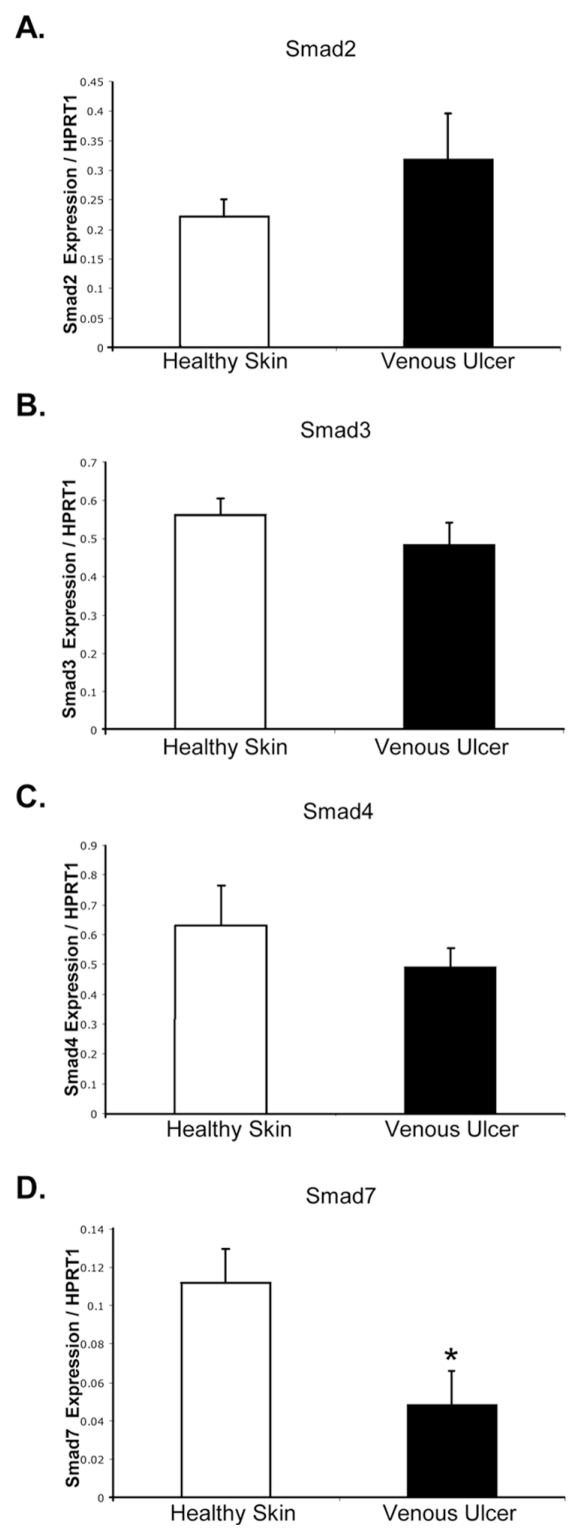

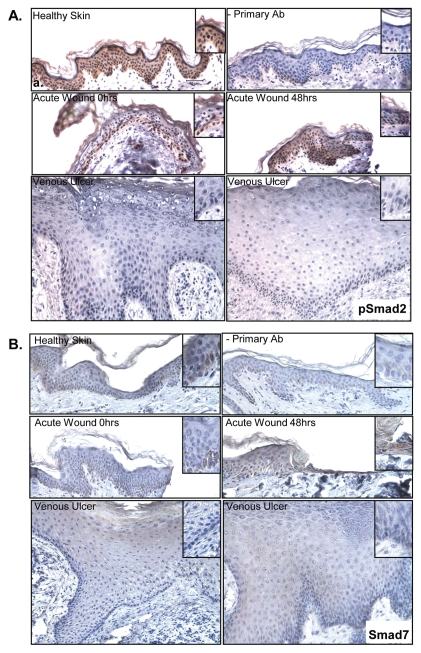

To further analyze expression of components of the TGFβ-signaling cascade, we determined mRNA levels for Smad2, 3, 4 and inhibitory Smad7 by qPCR in nonhealing edges of VUs (Figure 2). No significant changes in expression of Smad2, 3 and 4 genes were found. However, phosphorylated Smad2 (pSmad2) was absent in VUs as shown by immunohistochemistry, whereas high immunoreactivity for pSmad2 was observed in healthy skin. The levels of pSmad2 were also elevated in an ex vivo acute wound model. Furthermore, pSmad2 was present in the nuclei of cells comprising migrating epithelial tongue (Figure 3A). These data indicate that although mRNA levels of total Smad2 are not reduced in the edges of VUs compared with healthy skin, TGFβ signal transduction via Smad2 is impaired.

Figure 2.

Expression of Smad2, Smad3, Smad4 and Smad7 in VUs and healthy skin. Real-time qPCR results for the expression of Smad2 (A), Smad3 (B), Smad4 (C) and Smad7 (D). Error bars indicate mean ± SD. *Statistically significant differences between VUs and healthy skin were defined as P < 0.05.

Figure 3.

Phosphorylated Smad2 is absent and Smad7 does not contribute to the attenuation of TGFβ signaling in VUs. (A) Immunohistochemistry shows nuclear pSmad2 in basal keratinocytes in healthy skin, in acute wounds immediately upon wounding and in the migrating epithelial tongue 48 h after wounding. In contrast, no nuclear pSmad2 was observed in keratinocytes of VUs. (B) Smad7 is predominantly expressed in the basal layer in healthy skin and at the acute wound edge immediately after wounding. It is upregulated in migrating epithelial tongue 48 h after wounding and downregulated in VUs.

The inhibitory Smad protein Smad7 can bind to Smad complexes and inhibit Smad2 phosphorylation and nuclear translocation. Furthermore, Smad7 can cause degradation of TGFβ receptors. Therefore, we analyzed the presence of Smad7 in VUs. Smad7 mRNA and Smad7 protein were strongly downregulated in the epidermis of all VU tested compared with healthy skin (Figure 2D, 3B). The absence of Smad7 was most prominent in the basal layer of the VU epidermis (Figure 3B). These data suggest that in VUs TGFβ signaling via Smad2 is abrogated at the receptor level, and Smad7 does not contribute to decreased TGFβ signal transduction.

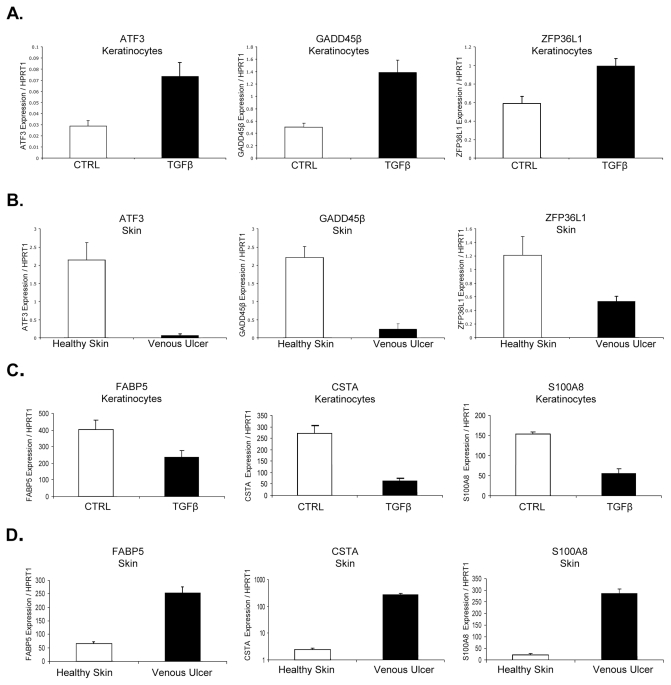

Expression of TGFβ Target Genes Is Deregulated in VUs

To determine whether reduction of TGFβ signaling via the Smad signaling cascade affects expression levels of TGFβ-dependent genes, we analyzed nonhealing edges of VUs for the expression levels of three TGFβ-inducible transcription factors and three genes that are suppressed by TGFβ (Figure 4), all found to be differentially regulated by comparative genomics. Specifically, we focused on TGFβ-inducible transcription factors, including growth arrest and DNA-damage-inducible β (GADD45β ), activating transcription factor 3 (ATF3) and zinc finger protein 36L1 (ZFP36L1). GADD45β is involved in the regulation of growth and apoptosis (43). ATF3 is a member of the mammalian activation transcription factor/cAMP responsive element-binding (CREB) protein family of transcription factors and a common target of TGFβ and stress signals (44). Primary human keratinocytes treated with TGFβ for 24 h served as controls. In conformity with published data using human keratinocyte cell line HaCaT (44,45), mRNA levels of ATF3, GADD45β and ZFP36L1 were upregulated in primary human keratinocytes after stimulation with TGFβ (Figure 4A). In contrast, the mRNA levels of ATF3, GADD45β and ZFP36L1 were downregulated in biopsies from VUs compared with healthy skin (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

ATF3, GADD45β and ZFP36L1 are suppressed while FABP5, S100A8 and CSTA are induced in VUs. mRNA levels of ATF3, GADD45β , ZFP36L1 (A, B) and mRNA levels of FABP5, S100A8 and CSTA (C, D) in TGFβ-treated keratinocytes and VUs measured by qPCR. Error bars indicate mean ± SD.

We next analyzed expression levels of TGFβ target genes that are found to be suppressed by TGFβ in keratinocytes: fatty acid binding protein 5 (FABP5), cystatin A (CSTA) and S100 calcium binding protein A8 (S100A8). FABP5 was first identified as being upregulated in psoriatic tissue (46) and has recently been described as a novel marker of human epidermal transit amplifying cells (47). CSTA (Stefin A) is one of the precursor proteins of the cornified cell envelope and plays a role in epidermal development and maintenance. Stefins have also been proposed as prognostic and diagnostic tools for cancer (48). S100A8 is upregulated in hyperproliferative and psoriatic epidermis and is a marker of inflammation. TGFβ suppresses S100A8 expression in murine fibroblasts (49). Expression levels of all three genes were reduced after stimulation of keratinocytes with TGFβ , and mRNA levels were significantly increased in wound edges of VUs compared with healthy skin (Figure 4C, D). Specifically, CSTA was 110-fold higher in VUs than in healthy skin (P < 0.01), and S100A8 levels were 13-fold higher in VUs than in healthy skin (P < 0.01). Taken together, our data demonstrate that deregulation of TGFβ signaling in nonhealing VUs occurs at multiple levels, all of which contribute to the overall pathogenesis of VUs. Deregulation is not only due to reduced TGFβ receptor expression, but also to abrogation of signal transduction via the Smad2 signaling cascade, leading to deregulation of TGFβ target genes.

DISCUSSION

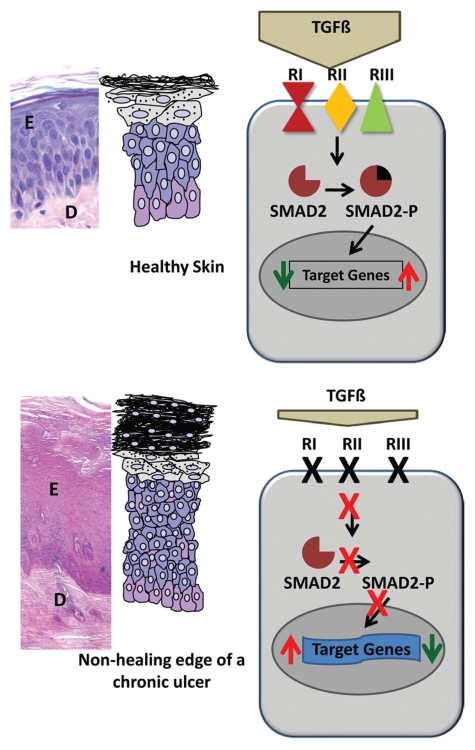

In this study, we investigated the mechanism of deregulation of TGFβ signaling in chronic VUs. The TGFβ signaling cascade is attenuated by downregulated expression of all three major receptors, loss of Smad2 activation, and deregulation of TGFβ target genes (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Attenuation of TGFβ signaling in VU. Top, histology of healthy skin. Cartoon summarizes a simplified signaling cascade in healthy epidermis. Bottom, histology of VU. In addition to decreased levels of TGFβ , downregulation of receptors followed by subsequent loss of pSmad2 leads to deregulation of TGFβ target genes and hyperproliferative epidermis of nonhealing VU.

Based on the therapeutic effect of topical application in animal models (50), TGFβ has been a promising therapeutic option for impaired wound healing. In rats and humans with impaired wound healing, overall TGFβ levels in wound fluid were shown to be diminished, and the normal elevation of TGFβ 1 found during acute wound healing was absent (21,51). Furthermore, differential expression of the TGFβ receptors in acute and chronic wounds has been described ((3,19,20)). However, TGFβ 1 failed to get into clinical trials (29). Our data demonstrate that TGFβ signaling is further impaired by reduced expression of the TGFβ receptors in the wound edge of VU in addition to decreased TGFβ levels. This impaired signaling leads to an abrogation of Smad2 activation and deregulation of TGFβ target genes. Functional loss of the TGFβ /Smad signaling cascade in VU offers an explanation for the limited ability of exogenous applications of TGFβ to accelerate wound healing in chronic wounds.

An important study analyzing TGFβ receptors using qPCR on biopsies of human nonhealing VUs has suggested that the absence of TGFβ RII contributes to the chronicity of these ulcers (20). The study also looked at TGFβ RI and found high expression throughout the thickened epidermal margin of the ulcers, including the suprabasal layers, and within fibroblasts in the dermal ulcer margin (20). In contrast, we found a complete absence of TGFβ RI and TGFβ RII and downregulation of TGFβ RIII. These differences in findings might be attributed to the wound location from which biopsies were taken. To assure that biopsies obtained indeed originated from non-healing tissue, we used a previously established marker (nuclearization of β-catenin) that demarcates nonhealing tissue within chronic wounds (30).

Inhibition of keratinocyte mitosis is an important step in the early stages of acute wound healing, when keratinocytes are being recruited to the wound edge to migrate and properly epithelialize the wound site (52). In addition to its role during cutaneous wound healing, TGFβ signaling plays a profound role in maintaining epithelial tissue homeostasis by suppressing proliferation (7). Because of this important role we focused on the TGFβ pathway in VUs compared with healthy skin and found suppression of signaling components. Our data suggest that attenuation of TGFβ signaling in VUs could contribute to the hyperproliferative phenotype of nonhealing epidermis (2,30). TGFβ responses include repression of growth-promoting transcription factors, most notably c-myc (53,54). This finding is in agreement with our previous data that showed elevated c-myc expression and the presence of β-catenin in the nucleus at the non-healing wound edge of VUs (30). Thus, we conclude that the lack of TGFβ signaling might contribute to c-myc over -expression and loss of cytostatic control in nonhealing VU epidermis (Figure 5). The transcription factors we found suppressed in VUs, GADD45β and ATF3 are also known to participate in TGFβ-mediated growth control in epithelial cells (44,55). ATF3 is also a stress response gene that can be activated by cellular stresses and mechanical injury (56,57). Its suppression in VUs suggests that epidermis in chronic wounds may be unresponsive to both stress and growth factor therapy.

Loss of responsiveness to TGFβ is a hallmark of many types of cancers (54,58). Although carcinomas are documented to arise at the site of chronic wounds, they are a relatively infrequent complication (59). Similar to chronic wounds, conditional knockout of TGFβ RII in stratified epithelia led to infrequent and localized tumor development only in older animals (60). Strong induction of CSTA in VUs may be an additional factor in providing protection against malignant transformation in VUs, because CSTA is reduced in skin cancers (61).

The role of Smad7, an inhibitor of the Smad signaling cascade, has not yet been studied in chronic wounds. Our study demonstrated profound downregulation of Smad7 in the basal layer of the epidermis of VUs, whereas Smad7 was upregulated in keratinocytes of acute wounds ex vivo. The human skin organ culture model has been extensively and reliably used to study epidermal wound healing ((33–37,62)); however, it was never used to analyze TGFβ signaling. Showing induction of Smad2 phosphorylation and up-regulation Smad7, we confirmed activation of TGFβ signaling in an acute ex vivo wound model. In a mouse model of acute wound healing, increased levels of Smad7 coincided with delayed reepithelialization of wounds, whereas downregulation of Smad7 accelerated reepithelialization (63). In contrast, we observed reduced expression of Smad7 in the basal epidermis of nonhealing wounds in parallel to reduced levels of pSmad2 and deregulated target gene expression. Thus, downregulation of Smad7 did not rescue TGFβ-signaling activity via the Smad cascade. This finding indicates that Smad7 is not responsible for the inhibition of TGFβ signaling in VUs, but instead the strong decrease in TGFβ receptor levels causes a functional knockdown of TGFβ signaling.

In summary, this study demonstrates that in the nonhealing wound edge of VUs, TGFβ signaling is attenuated by decreased expression of receptors, resulting in diminished activation of the Smad signaling cascade and subsequent deregulation of TGFβ target genes leading to loss of tissue homeostasis and hyperproliferation. Our results provide strong evidence that disruption of the TGFβ signaling cascade may be the underlying factor for failure of exogenous TGFβ to accelerate healing in chronic wounds.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to M Goldring and members of her laboratory (Hospital for Special Surgery) and G Guasch (Fuchs Lab, Rockefeller University) for helpful advice and technical assistance. We are also grateful to members of Tomic and Brem Laboratories for helpful suggestions and critical review. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1NR008029 (M Tomic-Canic), Rudolph Rupert Scleroderma Research Program (M Tomic-Canic), Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD (C Stuelten).

Footnotes

Online address: http://www.molmed.org

DISCLOSURE

The authors declare that they have no competing interests as defined by Molecular Medicine, or other interests that might be perceived to influence the results and discussion reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harsha A, et al. ADAM12: a potential target for the treatment of chronic wounds. J Mol Med. 2008;86:961–9. doi: 10.1007/s00109-008-0353-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stojadinovic O, et al. Deregulation of keratinocyte differentiation and activation: a hallmark of venous ulcers. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:2675–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00321.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim BC, et al. Fibroblasts from chronic wounds show altered TGF-beta-signaling and decreased TGF-beta type II receptor expression. J Cell Physiol. 2003;195:331–6. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hasan A, et al. Dermal fibroblasts from venous ulcers are unresponsive to the action of transforming growth factor-beta 1. Dermatol Sci. 1997;16:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0923-1811(97)00622-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agren MS, Steenfos HH, Dabelsteen S, Hansen JB, Dabelsteen E. Proliferation and mitogenic response to PDGF-BB of fibroblasts isolated from chronic venous leg ulcers is ulcer-age dependent. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;112:463–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00549.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrientos S, Stojadinovic O, Golinko MS, Brem H, Tomic-Canic M. Growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:585–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel PM, Massague J. Cytostatic and apoptotic actions of TGF-beta in homeostasis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:807–21. doi: 10.1038/nrc1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Kane S, Ferguson MW. Transforming growth factor beta s and wound healing. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1997;29:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(96)00120-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verrecchia F, Mauviel A. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling through the Smad pathway: role in extracellular matrix gene expression and regulation. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;118:211–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zambruno G, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 modulates beta 1 and beta 5 integrin receptors and induces the de novo expression of the alpha v beta 6 heterodimer in normal human keratinocytes: implications for wound healing. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:853–65. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Montesano R, Orci L. Transforming growth factor beta stimulates collagen-matrix contraction by fibroblasts: implications for wound healing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:4894–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.13.4894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schiller M, Javelaud D, Mauviel A. TGF-beta-induced SMAD signaling and gene regulation: consequences for extracellular matrix remodeling and wound healing. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell. 2003;113:685–700. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00432-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inman GJ, Nicolas FJ, Hill CS. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Smads 2, 3, and 4 permits sensing of TGF-beta receptor activity. Mol Cell. 2002;10:283–94. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00585-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nicolas FJ, De Bosscher K, Schmierer B, Hill CS. Analysis of Smad nucleocytoplasmic shuttling in living cells. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:4113–25. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Piek E, Heldin CH, Ten Dijke P. Specificity, diversity, and regulation in TGF-beta superfamily signaling. FASEB J. 1999;13:2105–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massague J. How cells read TGF-beta signals. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:169–78. doi: 10.1038/35043051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faler BJ, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta and wound healing. Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2006;18:55–62. doi: 10.1177/153100350601800123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid P, et al. TGF-beta s and TGF-beta type II receptor in human epidermis: differential expression in acute and chronic skin wounds. J Pathol. 1993;171:191–7. doi: 10.1002/path.1711710307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cowin AJ, et al. Effect of healing on the expression of transforming growth factor beta(s) and their receptors in chronic venous leg ulcers. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:1282–9. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jude EB, Blakytny R, Bulmer J, Boulton AJ, Ferguson MW. Transforming growth factor-beta 1, 2, 3 and receptor type I and II in diabetic foot ulcers. Diabet Med. 2002;19:440–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.00692.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper DM, Yu EZ, Hennessey P, Ko F, Robson MC. Determination of endogenous cytokines in chronic wounds. Ann Surg. 1994;219:688–91. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199406000-00012. discussion 691–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mustoe TA, et al. Accelerated healing of incisional wounds in rats induced by transforming growth factor-beta. Science. 1987;237:1333–6. doi: 10.1126/science.2442813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shah M, Foreman DM, Ferguson MW. Neutralisation of TGF-beta 1 and TGF-beta 2 or exogenous addition of TGF-beta 3 to cutaneous rat wounds reduces scarring. J Cell Sci. 1995;108:985–1002. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.3.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salomon GD, et al. Gene expression in normal and doxorubicin-impaired wounds: importance of transforming growth factor-beta. Surgery. 1990;108:318–22. discussion 322–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beck LS, et al. One systemic administration of transforming growth factor-beta 1 reverses age- or glucocorticoid-impaired wound healing. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2841–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI116904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sporn MB, Roberts AB. A major advance in the use of growth factors to enhance wound healing. J Clin Invest. 1993;92:2565–6. doi: 10.1172/JCI116868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robson MC, et al. Safety and effect of transforming growth factor-beta(2) for treatment of venous stasis ulcers. Wound Repair Regen. 1995;3:157–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475X.1995.30207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bennett SP, et al. Growth factors in the treatment of diabetic foot ulcers. Br J Surg. 2003;90:133–46. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stojadinovic O, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of chronic wounds: the role of beta-catenin and c-myc in the inhibition of epithelialization and wound healing. Am J Pathol. 2005;167:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)62953-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee B, et al. From an enhanceosome to a repressosome: molecular antagonism between glucocorticoids and EGF leads to inhibition of wound healing. J Mol Biol. 2005;345:1083–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stojadinovic O, et al. Novel genomic effects of glucocorticoids in epidermal keratinocytes: Inhibition of apoptosis, interferon-gamma pathway, and wound healing along with promotion of terminal differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:4021–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606262200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tomic-Canic M, et al. Streptolysin O enhances keratinocyte migration and proliferation and promotes skin organ culture wound healing in vitro. Wound Repair Regen. 2007;15:71–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2006.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kratz G. Modeling of wound healing processes in human skin using tissue culture. Microsc Res Tech. 1998;42:345–50. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19980901)42:5<345::AID-JEMT5>3.0.CO;2-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pullar CE, Grahn JC, Liu W, Isseroff RR. Beta2-adrenergic receptor activation delays wound healing. FASEB J. 2006;20:76–86. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-4188com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heilborn JD, et al. The cathelicidin anti-microbial peptide LL-37 is involved in re-epithelialization of human skin wounds and is lacking in chronic ulcer epithelium. J Invest Dermatol. 2003;120:379–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roupe KM, et al. Injury is a major inducer of epidermal innate immune responses during wound healing. J Invest Dermatol. 2009 2009 Sep 3; doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.284. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Randolph RK, Simon M. Characterization of retinol metabolism in cultured human epidermal keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:9198–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jho S, et al. The book of opposites: the role of the nuclear receptor co-regulators in the suppression of epidermal genes by retinoic acid and thyroid hormone receptors. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;124:1034–43. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cahan P, et al. List of lists-annotated (LOLA): a database for annotation and comparison of published microarray gene lists. Gene. 2005;360:78–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee DD, Zavadil J, Tomic-Canic M, Blumenberg M. Comprehensive transcriptional profiling of human epidermis, reconstituted epidermal equivalents and cultured keratinocytes, using DNA microarray chips. Methods Mol Biol. 2010;585:193–223. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-380-0_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banno T, Gazel A, Blumenberg M. Pathway-specific profiling identifies the NF-kappa B-dependent tumor necrosis factor alpha-regulated genes in epidermal keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:18973–80. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maeda T, et al. GADD45 regulates G2/M arrest, DNA repair, and cell death in keratinocytes following ultraviolet exposure. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:22–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2002.01781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kang Y, Chen CR, Massague J. A self-enabling TGFbeta response coupled to stress signaling: Smad engages stress response factor ATF3 for Id1 repression in epithelial cells. Mol Cell. 2003;11:915–26. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00109-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gomis RR, et al. A FoxO-Smad synexpression group in human keratinocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:12747–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605333103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Madsen P, Rasmussen HH, Leffers H, Honore B, Celis JE. Molecular cloning and expression of a novel keratinocyte protein (psoriasis-associated fatty acid-binding protein [PA-FABP]) that is highly up-regulated in psoriatic skin and that shares similarity to fatty acid-binding proteins. J Invest Dermatol. 1992;99:299–305. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12616641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.O’Shaughnessy RF, Seery JP, Celis JE, Frischauf A, Watt FM. PA-FABP, a novel marker of human epidermal transit amplifying cells revealed by 2D protein gel electrophoresis and cDNA array hybridisation. FEBS Lett. 2000;486:149–54. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(00)02252-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Keppler D. Towards novel anti-cancer strategies based on cystatin function. Cancer Lett. 2006;235:159–76. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rahimi F, Hsu K, Endoh Y, Geczy CL. FGF-2, IL-1beta and TGF-beta regulate fibroblast expression of S100A8. FEBS J. 2005;272:2811–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pierce GF, et al. Platelet-derived growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta enhance tissue repair activities by unique mechanisms. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:429–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.1.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bitar MS, Labbad ZN. Transforming growth factor-beta and insulin-like growth factor-I in relation to diabetes-induced impairment of wound healing. J Surg Res. 1996;61:113–9. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1996.0090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hebda PA, Sandulache VC. The Biochemistry of Epidermal Healing. In: Rovee DT, Maibach HI, editors. The Epidermis in Wound Healing. CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2004. pp. 59–86. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Alexandrow MG, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor beta and cell cycle regulation. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1452–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Massague J, Blain SW, Lo RS. TGFbeta signaling in growth control, cancer, and heritable disorders. Cell. 2000;103:295–309. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takekawa M, et al. Smad-dependent GADD45beta expression mediates delayed activation of p38 MAP kinase by TGF-beta. EMBO J. 2002;21:6473–82. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hai T, Wolfgang CD, Marsee DK, Allen AE, Sivaprasad U. ATF3 and stress responses. Gene Expr. 1999;7:321–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harper EG, Alvares SM, Carter WG. Wounding activates p38 map kinase and activation transcription factor 3 in leading keratinocytes. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:3471–85. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Derynck R, Akhurst RJ, Balmain A. TGF-beta signaling in tumor suppression and cancer progression. Nat Genet. 2001;29:117–29. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kirsner RS, et al. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in osteomyelitis and chronic wounds. Treatment with Mohs micrographic surgery vs amputation. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:1015–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.1996.tb00654.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guasch G, et al. Loss of TGFbeta signaling destabilizes homeostasis and promotes squamous cell carcinomas in stratified epithelia. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:313–27. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Strojan P, et al. Prognostic significance of cysteine proteinases cathepsins B and L and their endogenous inhibitors stefins A and B in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1052–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schmidtchen A, Holst E, Tapper H, Bjorck L. Elastase-producing pseudomonas aeruginosa degrade plasma proteins and extracellular products of human skin and fibroblasts, and inhibit fibroblast growth. Microb Pathog. 2003;34:47–55. doi: 10.1016/s0882-4010(02)00197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reynolds LE, et al. Alpha3beta1 integrin-controlled Smad7 regulates reepithelialization during wound healing in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:965–74. doi: 10.1172/JCI33538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]