Abstract

Synaptic transmission depends on neurotransmitter pools stored within vesicles that undergo regulated exocytosis. In the brain, the vesicular monoamine transporter-2 (VMAT2) is responsible for the loading of dopamine (DA) and other monoamines into synaptic vesicles. Prior to storage within vesicles, DA synthesis occurs at the synaptic terminal in a two-step enzymatic process. First, the rate-limiting enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) converts tyrosine to di-OH-phenylalanine. Aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) then converts di-OH-phenylalanine into DA. Here, we provide evidence that VMAT2 physically and functionally interacts with the enzymes responsible for DA synthesis. In rat striata, TH and AADC co-immunoprecipitate with VMAT2, whereas in PC 12 cells, TH co-immunoprecipitates with the closely related VMAT1 and with overexpressed VMAT2. GST pull-down assays further identified three cytosolic domains of VMAT2 involved in the interaction with TH and AADC. Furthermore, in vitro binding assays demonstrated that TH directly interacts with VMAT2. Additionally, using fractionation and immunoisolation approaches, we demonstrate that TH and AADC associate with VMAT2-containing synaptic vesicles from rat brain. These vesicles exhibited specific TH activity. Finally, the coupling between synthesis and transport of DA into vesicles was impaired in the presence of fragments involved in the VMAT2/TH/AADC interaction. Taken together, our results indicate that DA synthesis can occur at the synaptic vesicle membrane, where it is physically and functionally coupled to VMAT2-mediated transport into vesicles.

Keywords: Neurochemistry, Neurobiology/Neuroscience, Neurotransmitters, Subcellular Organelles/Vesicles, Transport, Transport/Amine, Dopamine, vesicular monoamine transporter

Introduction

Monoamines, including dopamine (DA),3 norepinephrine (NE), and serotonin (5-HT), are neurotransmitters that play major roles in a variety of brain functions, including emotion, reward, cognition, memory, attention, locomotion, and stress control (1–6). In neurons and neuroendocrine cells, monoamines are stored in large dense core vesicles (LDCVs) and small synaptic vesicles (SVs) (7–11) that undergo regulated exocytosis through a complex network of protein-protein interactions (12). Loading of monoamines into LDCVs and SVs of neurons and neuroendocrine cells is mediated by two vesicular monoamine transporter isoforms: VMAT1 (13) and VMAT2 (14). These transporters contain 12 putative transmembrane domains with both the N and C termini facing the cytosolic side of the vesicle membrane. VMAT1 is mostly present in LDCVs of neuroendocrine cells, including chromaffin and PC12 cells, whereas VMAT2 is primarily expressed by monoaminergic neurons of the central nervous system (15). In midbrain DA neurons, VMAT2 is sorted to LDCVs and SVs in axon terminals and to LDCVs and tubulo-vesicular structures in the somatodendritic compartment (7–11, 15).

It is generally accepted that VMAT2 transports DA that has been previously synthesized in the cytosolic compartment of the presynaptic terminal (16). DA synthesis requires two enzymatic reactions. First, tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) converts tyrosine into DOPA. TH is the rate-limiting enzyme in DA synthesis, and its regulated activity governs the overall rate of formation for DA (17, 18). Early studies showed that TH exists in both cytosolic and membrane-bound forms (19–22). Cytosolic TH is enriched in neuronal somatodendritic compartments of the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area (20, 23–27), whereas membrane-bound TH is more common in brain areas enriched in axon terminals (e.g. striatum and nucleus accumbens) (20, 23, 24). In the second enzymatic step of DA synthesis, aromatic amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) converts DOPA into DA (28). Less information is available regarding the subcellular distribution of AADC in monoaminergic neurons and chromaffin cells. To date, DA synthesis by TH and AADC and its transport into vesicles via the actions of VMAT2 have been regarded as two separate and independent events. Here, we provide evidence that VMAT2 and the enzymes responsible for synthesis of DA, TH, and AADC are physically and functionally coupled at the synaptic vesicle membrane. The physiological implications of these findings are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Male, Sprague-Dawley rats (350 g) between 8 and 10 weeks old were obtained from Hilltop Lab Animals, Inc. (Scottdale, PA). The antibodies against VMAT2 (AB1598P), VMAT1, TH, AADC, Na+/K+ ATPase, VGlut1, and GAD65/67 as well as the nonspecific IgGs from goat (PP40) and rabbit (PP64) were from Millipore (Billerica, MA). The VMAT2 C20 antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against synaptophysin, clathrin, and Rab5 were obtained from BD Transduction Laboratories (San Jose, CA). The SV2 and PSD93 antibodies were from Synaptic Systems (Gottingen, Germany). The monoclonal transferrin receptor antibody was supplied by Zymed Laboratories Inc. (San Francisco, CA). The SNAP-25 was purchased from Sigma. Secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase were from Jackson Immunoresearch (West Grove, PA). All other reagents were from Sigma unless stated otherwise.

Cell Culture

PC12 cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum, 5% horse serum, 1 mm glutamine, and 50 μg/ml each penicillin and streptomycin and maintained at 37 °C in a humidified, 10% CO2 incubator. In some cases, the PC12 cells were transiently transfected with the VMAT2 cDNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Preparation of Brain and PC12 Lysates

Rat whole brain or striata were homogenized with a Polytron homogenizer in buffer A (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 125 mm NaCl, 1 mm EGTA), containing protease inhibitors (Pierce). Triton X-100 was added to a final concentration of 1%, and the samples were incubated with rotation for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were centrifuged twice at 4 °C, first at 16,000 × g for 10 min and then at 20,000 × g for 60 min. The supernatant was collected, measured for protein concentration, and used in subsequent experiments. PC12 lysate was obtained using the same homogenization procedure but only subjected to one centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C.

Immunoprecipitation

Anti-VMAT2 (1:200), anti-VMAT1 (1:200), anti-TH (1:200), control IgGs (1:200), or no antibody (beads only) were added to either striata or cell lysates and incubated with rotation overnight or for 1 h at 4 °C. The next day, 50 μl of a mixture of protein A- and protein G-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) were added to all samples and incubated with rotation for an additional 1 h at 4 °C. Following centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 3 min, pellets were washed two times in buffer A containing 1% Triton X-100 and twice in PBS in the presence of protease inhibitors. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 30 μl of sample buffer containing 10% β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME) and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min prior to analysis using 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot.

GST Pull-down Assays

cDNA fragments encoding cytoplasmic domains of human VMAT2 (N terminus, residues 1–18; third cytoplasmic loop, residues 268–292; C terminus, residues 466–514) were amplified by PCR and subcloned into the pGEX4T-1 vector. Constructs containing GST fusion domains were sequenced, expressed in bacteria, and purified as described previously (29). Briefly, recombinant constructs were transformed into BL21 Escherichia coli, grown for 24 h, treated with 0.1 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside for 4 h at 37 °C and harvested by centrifugation at 4,300 × g for 10 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in buffer B (50 mm EDTA in PBS) containing protease inhibitors. Bacterial cells were sonicated and lysed in 1% Triton X-100. Following incubation for 1 h at 4 °C, samples were centrifuged at 9,500 × g for 10 min. The resulting supernatants were then immobilized with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads (GE Healthcare). Even amounts of immobilized GST fusion proteins or GST only were incubated with brain lysate or buffer A alone overnight or for 1 h with rotation at 4 °C. The samples were centrifuged, and the resulting pellets were washed twice in buffer A containing 1% Triton X-100 and twice in PBS, all with protease inhibitors. These samples were suspended in 30 μl of protein sample buffer containing 10% β-ME and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min prior to analysis using 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot.

Purification of Recombinant His6-TH

Plasmid TH in the pQE30 vector (Qiagen) for prokaryotic expression of His6-tagged proteins was a kind gift from Dr. Janis O'Donnell (University of Alabama). The DNA was used to transform competent M15 bacterial cells and purified with Ni2+-NTA Superflow columns (Qiagen) according to the protocols of Funderburk et al. (30).

In Vitro Binding Assay

50 μg of recombinant His6-TH and 50 μg of purified GST-VMAT2N, GST-VMAT2L3, GST-VMAT2C, or GST only were diluted in 400 μl of buffer A. Following overnight incubation at room temperature with rotation, 50 μl of the glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads were added and incubated for another 3 h at room temperature with rotation. The beads were washed three times with cold PBS containing 1% Triton X-100, pH 7.65 for 1 min each. 50 μl of sample buffer containing 10% β-ME was added to the washed beads and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min to release bound proteins prior to Western blot analysis.

Preparation of an Enriched Synaptic Vesicle Fraction

Rat brain or striatum tissue was homogenized in buffer C (0.32 m sucrose in phosphate-buffered saline) supplemented with protease inhibitors. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to remove nuclei and cellular debris (P1). The supernatant (S1) was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min at 4 °C to yield a crude synaptosomal pellet (P2). This pellet was hypo-osmotically lysed in water containing protease inhibitors for 5 min at 4 °C and passed through both a 22- and 27½-gauge needle. This suspension was centrifuged at 23,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant (S3) was centrifuged again at 267,000 × g for 2 h at 4 °C in a TLA 110 Beckman rotor. The final pellet (called P4) contained an enriched fraction of synaptic vesicles and was used for subsequent experiments.

Purification of Synaptic Vesicles

In order to obtain purified synaptic vesicles, we isolated vesicles based on the protocol described by Morciano et al. (31) with some modifications. Whole brain from rat was homogenized with 20 strokes in a glass Teflon homogenizer in 10 volumes of 0.32 m sucrose, 5 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4, supplemented with protease inhibitors. The homogenate was centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was discarded, and the entire supernatant was layered on top of a discontinuous Percoll gradient, prepared using three different layers of Percoll solutions (3, 10, and 23% (v/v)) diluted in the original homogenization buffer. The Percoll gradient was centrifuged at 31,400 × g for 20 min at 4 °C, and the turbid fraction was collected containing isolated synaptosomes. Four volumes of the original homogenization buffer were added to the synaptosomes, and the sample was centrifuged again at 20,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was hypo-osmotically lysed in 6.5 ml of 5 mm Tris/HCl, pH 7.4) by pipetting the sample up-down-up 20 times and passing the sample through both a 22- and 27½-gauge needle. This suspension was centrifuged at 188,000 × g for 2 h at 4 °C. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 0.5 ml of sucrose buffer (200 mm sucrose, 0.1 mm MgCl2, 0.5 mm EGTA, 10 mm HEPES, pH 7.4) and layered onto a discontinuous sucrose gradient ranging from 0.3 to 1.2 m sucrose (both prepared in 10 mm HEPES, 0.5 mm EGTA, pH 7.4). The sucrose gradient was centrifuged at 85,000 × g for 2 h at 4 °C, and 500-μl fractions were collected from top to bottom and analyzed using Western blot.

Synaptic Vesicle Immunoisolation

The sucrose gradient fractions containing purified synaptic vesicles were pooled, adjusted to contain 1.2 mm CaCl2 and 1.2 mm of MgSO4, and immunoisolated using the anti-VMAT2 (AB1598P) antibody. Specifically, anti-VMAT2 (1:100) or control IgG (1:100) was added to 1 ml of the synaptic vesicle pool and incubated with rotation overnight or for 1 h at 4 °C. The next day, 50 μl of a mixture of protein A- and protein G-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) were added to all samples and incubated with rotation for an additional 1 h at 4 °C. Following centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 3 min, pellets were washed two times with cold PBS in the presence of protease inhibitors. The resulting pellets were resuspended in 30 μl of sample buffer containing 10% β-ME and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min prior to analysis using 10% SDS-PAGE and immunoblot.

Western Blot Analysis

Samples containing 10% β-ME were incubated at 37 °C for 30 min, separated by SDS-PAGE on 10% Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gels, and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes using the Bio-Rad system. Lysates were used in all experiments as positive control. Nitrocellulose membranes were first blocked for 1 h in TBS buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, 150 mm NaCl, 0.2% Tween 20) containing 5% dry milk and then incubated with the indicated primary antibody for 1 h in blocking buffer, washed three times for 10 min each, and incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Following all antibody incubations, membranes were washed three times with TBS buffer, and protein bands were visualized using the West Pico system (Pierce). Primary antibodies included anti-TH (1:1,000), anti-AADC (1:500), anti-VMAT2 AB1598P (1:500), anti-VMAT1 (1:500), anti-synaptophysin (1:15,000), anti-Na/K-ATPase (1:1,000), anti-SV2 (1:1,000), anti-synaptogyrin-3 (1:500), anti-PSD93 (1:1,000), anti-Rab5 (1:5,000), anti-transferrin receptor (1:1,000), anti-clathrin (1:1,000), anti-SNAP25 (1:5,000), and anti-GAD65/67 (1:1,000).

TH Activity

TH activity was measured according to Perez et al. (32) and Reinhard et al. (33) with minor modifications. Using this assay, 1 mol of [3H]H2O is generated for each mol of l-[3H]tyrosine that is converted to DOPA by TH and is therefore a direct measurement of TH activity. 100 μl of sample was added to an equal volume of 2× assay buffer to bring the final concentrations to 150 mm Tris-maleate, 50 μm unlabeled l-tyrosine, 0.4 μCi/mmol l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine (PerkinElmer Life Sciences), 5 mm ascorbate, 0.45 mg/ml catalase, 1 mm TH co-factor BH4 at pH 6.8. Samples were incubated for 25 min at 37 °C, and reactions were stopped on ice. Released [3H]H2O was separated from l-[3H]tyrosine using 7.5% charcoal/HCl. Because BH4 is an essential co-factor for TH activity, nonspecific background was determined in the absence of BH4. [3H]H2O was then added to 4 ml of Biosafe II scintillation liquid (Research Products International, Mount Prospect, IL), and radioactivity was counted in a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Synthesis and Vesicular Uptake Assay

250 μg of uptake buffer (50 mm HEPES, 90 mm KCl, 2.5 mm MgSO4, 2 mm ATP, 5 mm C6H8O6, 12 mm phosphoenolpyruvic acid, 0.2 mm pyridoxal-5-phosphate, 100 μg/μl pyruvate kinase, 500 μm tetrahydrobiopterin, pH 7.4) containing 100 μg of P4 was warmed to 29 °C prior to the addition of 1 μm l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Following incubation for 6 min, the samples were filtered through a 0.2-μm SUPOR membrane filter. The reaction was stopped by washing twice with 1.5 ml of cold uptake buffer. The filter was then added to 4 ml of Biosafe II scintillation liquid, and radioactivity was counted in a Beckman LS 6500 scintillation counter. In some cases, the uptake buffer was altered to contain a 100 μm concentration of the TH inhibitor α-methyl-p-tyrosine (α-MPT), 10 μm VMAT2 inhibitor reserpine, 1 mm AADC inhibitor m-hydroxybenzylhydrazine (NSD 1015), or the indicated amounts of either immobilized or eluted GST-VMAT2N, GST-VMAT2L, or GST- VMAT2C fusion proteins. Control experiments were performed in the presence of 1 μm [3H]DA (3,4-[7-3H]dihydroxyphenylethylamine, 34.8 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer) instead of l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine.

Data Analysis

Results are presented as mean ± S.E. Significant differences between means were determined by Student's t test with p < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

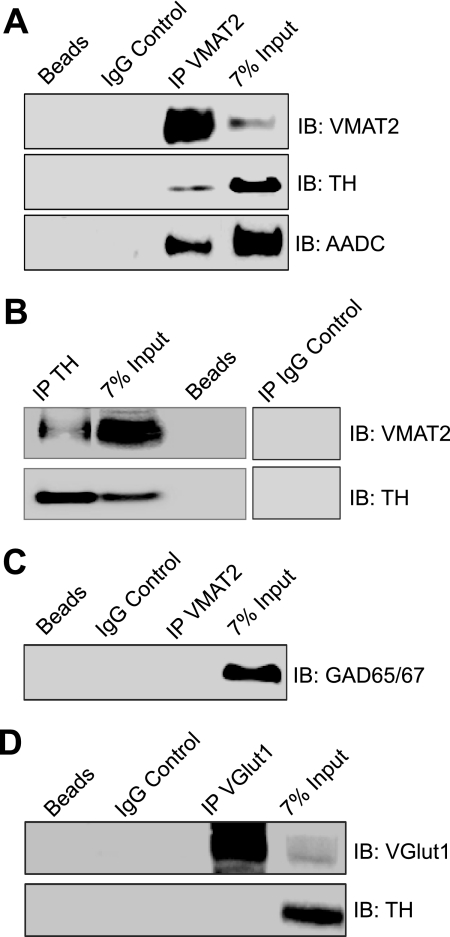

VMAT2 Co-immunoprecipitates with TH and AADC in Brain

To test the hypothesis that VMAT2 might interact with the enzymes responsible for DA synthesis, immunoprecipitation experiments were performed in rat striatum lysates. The striatum was chosen for these experiments because it is enriched in dopaminergic synaptic terminals expressing high levels of VMAT2 and TH (23, 24, 26). First, striata lysates were incubated with a VMAT2 antibody raised against the C-terminal domain from Millipore (AB1598). Immunoblot analysis of the samples with the VMAT2 and TH antibodies showed that both proteins co-precipitated (Fig. 1A). We also examined the possibility that AADC might associate with VMAT2 in striatum. Indeed, immunoprecipitation of VMAT2 co-precipitates AADC from striata. No bands were present in samples incubated without antibody (beads) or in samples incubated with the corresponding nonspecific IgG. Furthermore, immunoprecipitation experiments using an additional VMAT2 antibody from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. produced similar results (data not shown). Next, the reciprocal immunoprecipitation was performed in the same manner using a TH antibody. In agreement with our previous finding, VMAT2 co-precipitated with TH but was excluded from the beads only and IgG controls (Fig. 1B). The specificity of the VMAT2/TH interaction was then confirmed by demonstrating that VMAT2 failed to co-precipitate GAD65/67 (Fig. 1C), an enzyme responsible for the synthesis of GABA (34). Furthermore, TH and the unrelated vesicular glutamate transporter (VGlut) failed to co-precipitate (Fig. 1D).

FIGURE 1.

VMAT2 co-immunoprecipitates with TH and AADC from rat striata. A, immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments were performed by incubating rat striatum lysates with the VMAT2 antibody. Analysis using SDS-PAGE and immunoblot (IB) with the anti-VMAT2 (top), the anti-TH (middle), and the anti-AADC antibodies (bottom) demonstrated co-precipitation of these proteins. No bands were detected in the control samples incubated with either no antibody (Beads) or the nonspecific IgG. B, reciprocal experiments were also performed using the TH antibody for immunoprecipitation. Again, TH and VMAT2 co-precipitated and were absent from the control experiments. C, experiments performed using the VMAT2 antibody for immunoprecipitation showed that GAD65/67, an enzyme responsible for GABA synthesis, failed to co-precipitate with VMAT2. D, similarly, TH and the unrelated vesicular glutamate transporter (VGlut1) failed to co-precipitate. The last two experiments confirmed the specificity of the VMAT2/TH interaction.

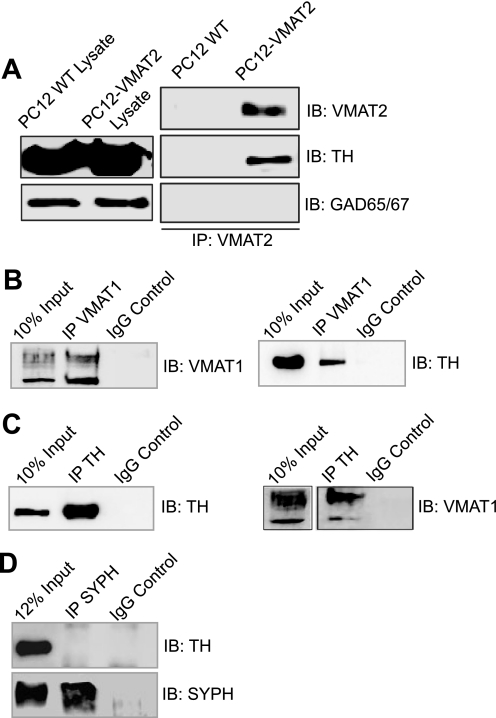

To further examine the VMAT2/TH interaction, we transfected PC12 cells with VMAT2 cDNA and performed immunoprecipitation experiments. As shown in Fig. 2A, TH co-precipitated with VMAT2 only in transfected cells and not in mock-transfected PC12 cells, demonstrating the specificity of the interaction. Again, immunoprecipitation of VMAT2 failed to co-precipitate GAD65/67 in both transfected and mock cells, further confirming the specificity of the VMAT2/TH interaction. Next, we investigated the possibility that TH might also be associated with the related VMAT1 isoform. VMAT1 is present in peripheral tissue and some cell lines, including PC12 cells. Thus, PC12 cell lysate was incubated with the VMAT1 antibody (Fig. 2B) or the TH antibody (Fig. 2C). In both cases, VMAT1 and TH were able to specifically precipitate each other and were absent from the nonspecific IgG control (Fig. 2, B and C). Finally, we examined if TH also interacted with the synaptic vesicle protein, synaptophysin. As shown in Fig. 2D, immunoprecipitation of synaptophysin failed to co-precipitate TH. Collectively, these results demonstrate that VMAT specifically interacts with TH and AADC.

FIGURE 2.

TH co-precipitates with VMAT1 and overexpressed VMAT2 in PC12 cells. A, immunoprecipitation (IP) experiments were also performed in both wild-type (WT) and VMAT2-transfected PC12 cell lysates using the VMAT2 antibody. The samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot (IB) for VMAT2 (top), TH (middle), and GAD65/67 (bottom). VMAT2 and TH co-precipitated in the VMAT2-transfected PC12 cells but were absent from the wild-type PC12 cells. GAD65/67 was not co-precipitated in either cell line, supporting the specificity of the VMAT2/TH interaction. Lysates from both wild type- and VMAT2-transfected cells are also shown. B, immunoprecipitation with a VMAT1 antibody results in the co-precipitation of VMAT1 (left) and TH (right). No bands were detected in the samples immunoprecipitated with the nonspecific IgG control. C, immunoprecipitation with the TH antibody results in the co-precipitation of TH (left) and VMAT1 (right). No bands were detected in the samples immunoprecipitated with the nonspecific IgG control. D, as an additional specificity control, wild-type PC12 cell lysate was immunoprecipitated with the synaptophysin (SYPH) antibody. Analysis by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot showed that TH failed to co-precipitate with synaptophysin, further confirming the specificity of the VMAT2/TH interaction. Whole cell lysate and immunoprecipitation with nonspecific IgG are also shown.

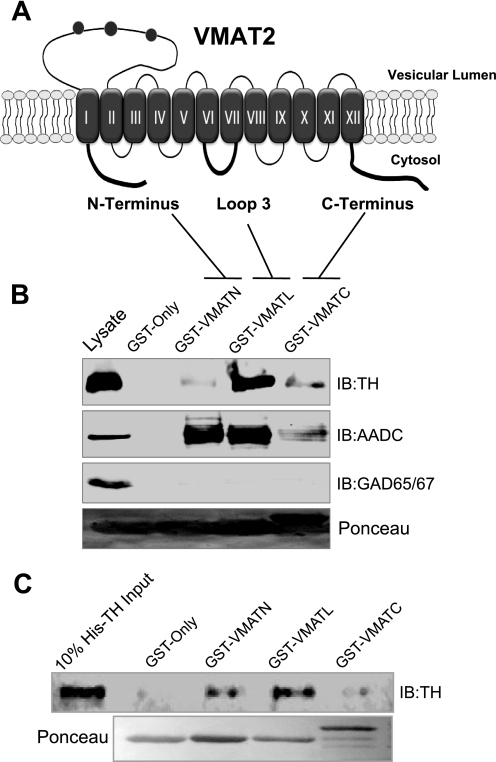

Cytosolic Domains of VMAT2 Are Involved in the Interaction with TH and AADC

Having established that TH and AADC associate with VMAT2, we next sought to identify which VMAT2 domains are involved in this interaction. Because DA synthesis occurs outside the synaptic vesicle, we tested the hypothesis that VMAT2 domains facing the cytosolic side of the vesicle membrane are involved in the interaction with TH and AADC. Thus, we generated GST fusion proteins expressing three VMAT2 cytosolic domains: GST-VMAT2N (residues 1–18, corresponding to the amino terminus), GST-VMAT2L3 (residues 268–292, corresponding to the third loop between transmembrane domains 6 and 7), and GST-VMAT2C (residues 466–514, corresponding to the C terminus) (Fig. 3A). These domains were chosen because they were large enough to contain putative interacting sites. Subsequently, rat brain lysates were incubated with even amounts of one of these fusion proteins or GST only to perform pull-down assays. As seen in Fig. 3B (first panel), a strong interaction was observed between TH and GST-VMAT2L3 (Fig. 3A), whereas weaker interactions were observed with GST-VMAT2N and GST-VMAT2C. On the other hand, AADC preferentially precipitated with GST-VMAT2N and GST-VMAT2L3 and to a much lesser degree with GST-VMAT2C (Fig. 3B, second panel). These interactions were considered specific because no bands were seen in the GST-only samples. In addition, as a negative control, we tested the ability of our GST-VMAT2 fragments to pull down GAD65/67. No bands were detected in any of our pull-down conditions (Fig. 3B, third panel).

FIGURE 3.

Cytosolic VMAT2 domains interact with TH and AADC. A, schematic representation of VMAT2 depicting 12 putative transmembrane domains with both the N and C termini facing the cytosolic side of the synaptic vesicle membrane. GST fusion proteins contained one of three cytosolic regions of VMAT2: the N terminus (GST-VMAT2N), the third loop between transmembrane domains 6 and 7 (GST-VMAT2L3), and the C terminus (GST-VMAT2C). B, even amounts of immobilized GST fusion proteins were used for pull-down experiments in rat brain lysates. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot (IB) with the TH (first panel) and AADC (second panel). As a negative control, the pull-down samples were also analyzed using the unrelated GAD65/GAD67 antibody (third panel), and no bands were detected in any of these samples. Lysate controls are shown for each immunoblot and Ponceau red (fourth panel) staining shows even loading of the fusion proteins. C, in vitro binding assays were performed by incubating purified His6-TH with even amounts of the GST fusion proteins or GST only. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot for TH (top). Lysate controls and Ponceau red staining are also shown (bottom).

Next, to determine whether these interactions were direct or mediated by additional proteins, we performed in vitro binding assays using a purified His6-TH protein in pull-down assays with our VMAT2-containing GST fusion proteins. As shown in Fig. 3C, purified TH co-precipitated strongly with VMAT2L3 and to a lesser degree with VMAT2N and VMAT2C. No interaction was detected in control experiments where purified TH was incubated with GST only. These results are consistent with our previous GST pull-down data using brain lysates. Thus, together these data confirm the interaction observed with co-immunoprecipitation assays, identifies multiple domains of VMAT2 involved in the VMAT2/TH interaction, and demonstrates that VMAT2 and TH bind directly.

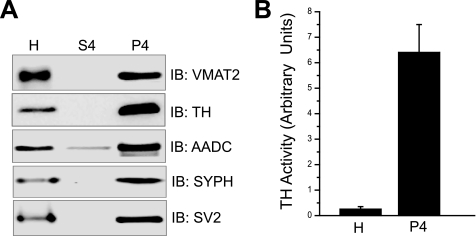

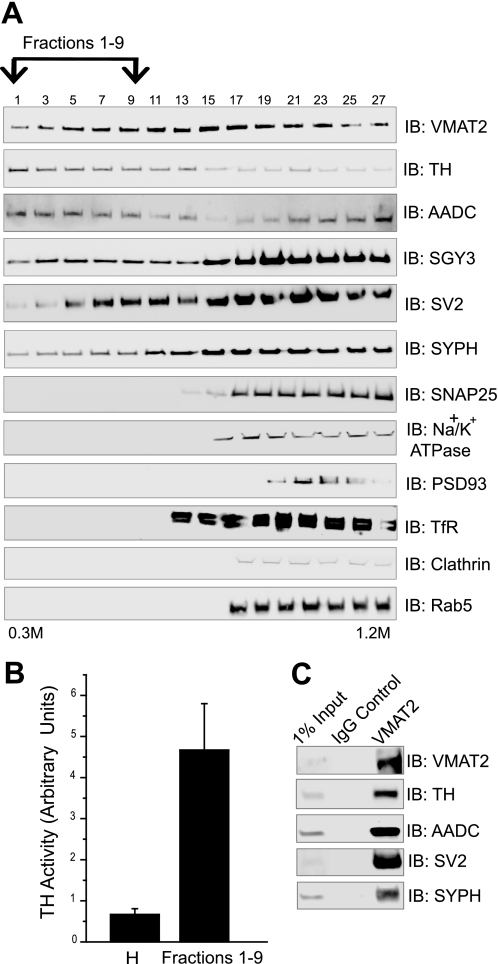

TH and AADC Co-fractionate with VMAT2 in Purified Synaptic Vesicles

Having demonstrated a physical interaction between VMAT2, TH, and AADC by two independent approaches, we next examined if these three proteins are localized to the same subcellular compartment. Thus, we obtained an enriched synaptic vesicle fraction (called P4) from rat striata. Our data confirmed that TH and VMAT2 along with other synaptic vesicle proteins, including SV2 and synaptophysin, were enriched in our P4 fraction compared with the initial homogenate (Fig. 4A). Next, we tested whether the P4 fraction contained TH activity. Indeed, significant TH activity was present and highly enriched in P4 when compared with the initial homogenate (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Active TH co-isolates with synaptic vesicles. A, an enriched synaptic vesicle preparation (P4) was obtained from rat striata. 15-μg samples of the original tissue homogenate (H) as well as the final supernatant (S4) and pellet (P4) in the enrichment process were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot (IB) using the VMAT2, TH, SV2, and synaptophysin (SYPH) antibodies. B, comparison between the TH activity present in the original homogenate (H) and P4. Activity is expressed in arbitrary units.

We next purified synaptic vesicles from rat whole brain using Percoll and sucrose gradients to examine if TH and AADC truly associate with synaptic vesicles. Consistent with previous results of Morciano et al. (31), Western blot analysis showed that the synaptic vesicle markers synaptogyrin-3, synaptophysin, SV2, and VMAT2 were distributed throughout the entire gradient (Fig. 5A). Only the lighter fractions (fractions 1–11) were devoid of other contaminants (Fig. 5A) and were considered pure synaptic vesicles. Specifically, fractions 1–11 lacked the plasma membrane marker Na+/K+ ATPase and other tested markers, such as SNAP-25 (presynaptic plasma membrane marker), PSD93 (postsynaptic marker), transferrin (early endosome marker), clathrin (early endosome marker), and Rab5 (early endosome marker), all of them present in the denser sucrose fractions (Fig. 5A). More importantly, TH and AADC were present in the lighter fractions containing only synaptic vesicle markers (Fig. 5A), demonstrating that TH and AADC associate with synaptic vesicles in the brain. Additionally, the purified synaptic vesicle pool displayed TH activity significantly greater than that obtained from the original homogenate (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

TH and AADC associate with immunoisolated VMAT2-containing synaptic vesicles. A, synaptic vesicles were purified using a discontinuous sucrose gradient (0.3–1.2 m). The gradient was divided into 30 fractions from top to bottom. The odd-numbered fractions were resolved by Western blot and probed with the appropriate antibodies against the proteins VMAT2, TH, and AADC as well as synaptogyrin 3 (SGY3), SV2, and synaptophysin (SYPH), to show the presence of synaptic vesicles. SNAP 25 was used as a presynaptic membrane marker; Na+/K+ ATPase was used to represent plasma membrane fractions; PSD93 was used to represent postsynaptic fractions; and transferrin (TfR), clathrin, and Rab5 were used as early endosomal markers. Fractions 1–9 contain purified synaptic vesicles. TH, AADC, and VMAT2 co-fractionate with these purified synaptic vesicles. B, TH activity was measured in fractions 1–9. TH activity in the purified synaptic vesicle fraction is enriched compared with the original homogenate. Activity is expressed in relative units, and data correspond to a representative experiment. C, fractions 1–9 were pooled and incubated with the anti-VMAT2 antibody or control IgG for immunoisolation experiments. The immunoisolated samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblot (IB) using the VMAT2, TH, AADC, synaptophysin, and SV2 antibodies. The immunoisolated samples show that TH and AADC co-isolate with VMAT2-containing synaptic vesicles. No bands were detected in the IgG controls.

Although TH and AADC associate with synaptic vesicles, the question as to whether this association was truly with VMAT2-containing synaptic vesicles still remained. Thus, we used the synaptic vesicle pool (fractions 1–9) for subsequent immunoisolation experiments. We used the anti-VMAT2 antibody for immunoisolation. As shown in Fig. 5C, immunoblot analysis of these samples showed that VMAT2, TH, and AADC as well as the synaptic vesicle markers SV2 and synaptophysin all co-immunoisolated. No bands were detected in the samples incubated with the IgG control. Together with our sucrose gradient data, these results demonstrate that TH and AADC associate with VMAT2-containing synaptic vesicles.

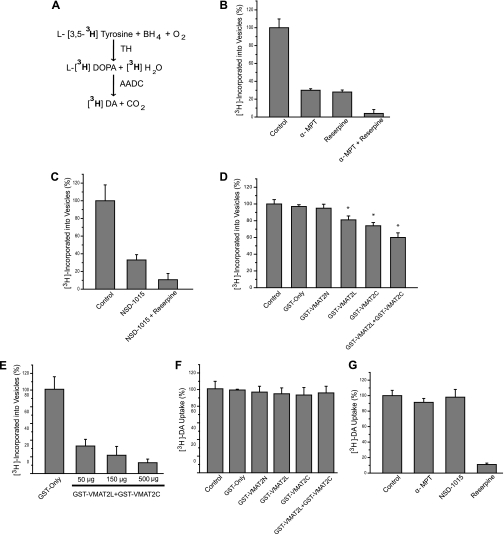

The Coupling between DA Synthesis and Vesicular Uptake Is Impaired in the Presence of VMAT2-interacting Domains

We next investigated whether the VMAT2/TH/AADC interaction provided the molecular basis of a coupling mechanism between DA synthesis and vesicular transport. To do this, we needed to have an assay where both synthesis and transport occur simultaneously. Thus, we incubated our enriched synaptic vesicle preparation (P4) with the TH substrate l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine for 6 min, separated the vesicles by filtration, and measured how much radioactivity was incorporated into vesicles. Using l-tyrosine that was labeled with tritium on two carbons allowed not only the production of [3H]H2O (which was used to measure TH activity) but also the production of [3H]DA, which is used to measure vesicular uptake of newly synthesized DA (Fig. 6A). The identity of the incorporated radioactivity was then characterized by using the TH inhibitor α-MPT and the VMAT2 inhibitor reserpine. If the radioactivity was due to l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine incorporated into vesicles, the levels would remain unaltered when TH is inhibited with α-MPT. On the contrary, our results actually showed that about 70% of the radioactivity incorporated was inhibited by α-MPT, suggesting that most of the l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine was transformed prior to vesicular uptake (Fig. 6B). Similarly, ∼70% of the incorporated radioactivity was blocked by the VMAT2 inhibitor reserpine, suggesting that the appropriate radioactive substrate was transported into vesicles by VMAT2. Moreover, the presence of both α-MPT and reserpine abolished the incorporation of radioactivity (Fig. 6B). Consistently, inhibition of AADC by NSD 1015 also produced an ∼70% reduction in incorporated radioactivity, whereas the presence of both NSD 1015 and reserpine produced an ∼90% decrease of incorporated radioactivity (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these results suggest that the radioactivity incorporated into vesicles is attributed to [3H]DA, which was previously synthesized from l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine.

FIGURE 6.

The coupling between DA synthesis and vesicular uptake is impaired in the presence of VMAT2-interacting domains. A, schematic representation of the [3H]DA from l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine. Note that this conversion also releases 1 molecule of [3H]H2O. B, incorporated radioactivity was measured in vesicular uptake assays using l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine in the uptake buffer. Total incorporated was determined with normal uptake buffer and is displayed as 100%. 1 mm reserpine and 10 μm α-methyltyrosine both inhibit incorporated radioactivity by 70%. When both inhibitors are used together, the vesicular uptake was almost abolished. C, similar experiments were performed in the presence of the AADC inhibitor 1 μm NSD 1015. Again, a 70% reduction in incorporated radioactivity was observed in the presence of NSD 1015 and reduced levels of incorporated radioactivity by about 90% in the presence of both reserpine and NSD 1015 as compared with control experiments. These results suggest that most of the l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine was transformed into [3H]DA prior to vesicular uptake. D, using this assay that involved both synthesis and transport of [3H]DA, similar experiments were performed in the presence of immobilized GST fusion proteins containing interacting, cytosolic VMAT2 domains involved in the VMAT2/TH/AADC interaction. The interacting GST-VMAT2 fusion constructs (GST-VMAT2L3 and GST-VMAT2C) were able to partially inhibit vesicular uptake. GST alone was used as a negative control. E, to characterize the effect of GST, GST-VMAT2L3, and GST-VMAT2C, these proteins were eluted from the beads and used in similar assays. These fusion proteins produced a dose-dependent decrease in incorporated radioactivity as compared with uptake in the presence of GST only. F, vesicular uptake experiments were performed using [3H]DA as the substrate in the presence of the immobilized GST fusion proteins containing interacting domains of VMAT2. Uptake of [3H]DA was unaffected by these fusion proteins, ruling out the possibility of a direct effect on VMAT2 activity. G, as an additional control, vesicular uptake assays using [3H]DA substrate were performed in the presence of the three inhibitors used in prior experiments. [3H]DA was significantly decreased only by 1 mm reserpine and was unaffected by either 10 μm α-MPT or 1 μm NSD 1015, demonstrating the specificity of these inhibitors. Taken together, these results suggest that the VMAT2/TH/AADC interaction has a functional role in coupling the synthesis and vesicular transport of DA.

Thus, having established an assay that allowed measurement of newly synthesized DA incorporated into vesicles, we next examined the effect of VMAT2-interacting domains on our synthesis/vesicular uptake assay. Even amounts of immobilized GST fusion proteins containing the interacting cytosolic domains of VMAT2 were added to the uptake buffer as potential competitors. Both GST-VMAT2L3 and GST-VMAT2C significantly reduced the incorporated radioactivity as compared with control buffer (Fig. 6D). Furthermore, GST-VMAT2L3 and GST-VMAT2C fragments when added together produced a greater inhibition of incorporated radioactivity. No significant decreases in incorporated radioactivity were observed in the presence of GST-VMAT2N or the GST only, confirming the specificity of the inhibitory actions of the fusion proteins. To characterize in detail the inhibitory effect of these VMAT2 fragments, we eluted the GST fusion proteins from the Sepharose beads and measured protein concentration. As seen in Fig. 6E, a dose-dependent inhibition of incorporated radioactivity occurred in the presence of the competing VMAT2L3 and VMAT2C fusion proteins as compared with the GST-only samples (∼70–90% inhibition). To rule out the possibility that the inhibitory effect observed was due to a direct effect on VMAT2 activity, we repeated the uptake experiment by incubating our samples with [3H]DA as opposed to l-[3,5-3H]tyrosine. This strategy bypasses DA synthesis by TH and AADC and allows the assessment of isolated VMAT2 activity. As shown in Fig. 6F, none of the fragments examined had any effect on VMAT2-mediated DA uptake, demonstrating that these competing fragments did not have any direct effect on the transporter. In the same manner, we also examined if α-MPT and NSD 1015 had an effect on DA uptake. Indeed, neither α-MPT nor NSD 1015 had any effect on DA uptake (Fig. 6G), further showing the specificity of these two compounds. Taken together, these results suggest that the VMAT2/TH/AADC interaction has a functional role in coupling the synthesis and vesicular transport of DA.

DISCUSSION

In this report, we provide several lines of evidence showing that VMAT2 physically and functionally interacts with the enzymes responsible for DA synthesis, TH and AADC. First, immunoprecipitation experiments in rat striata lysates showed that VMAT2 coprecipitates with TH and AADC. Similarly, the closely related VMAT1 and TH coprecipitated from PC12 cell lysates. Second, GST pull-down binding assays in rat brain demonstrated that multiple cytosolic domains of VMAT2 are involved in interactions with TH and AADC. Third, using purified proteins, we demonstrate a direct binding between VMAT2 and TH. Fourth, using fractionation and immunoisolation experiments, we show that TH and AADC are associated with VMAT2-containing synaptic vesicles. Fifth, TH activity was demonstrated in purified synaptic vesicles. Finally, the coupling between DA synthesis and vesicular transport was significantly impaired in a dose-dependent manner in the presence of VMAT2-interacting domains. These results provide evidence for a physical interaction between VMAT2, TH, and AADC that supports a coupling mechanism between the synthesis of DA and its transport into synaptic vesicles.

Although our immunoprecipitation experiments demonstrate an interaction between VMAT2 and TH/AADC, it is difficult to assess the extent of these interactions. Quantitative analysis of the immunoprecipitation experiments is a complex issue to address because the amount of protein that co-precipitates depends on several factors, including the strength of a given protein-protein interaction, the ability of the interaction to be extracted intact (lysis buffer conditions), the transient nature of the interaction, the ability of the antibody to extensively precipitate the proteins of interest, and the existence of a non-interacting pool of the proteins of interest. This last point is especially relevant, considering that TH exists as two subcellular forms, cytosolic and membrane-bound (19–22). Recently, active TH has also been demonstrated to associate with mitochondria, further supporting the notion of multiple cytosolic and membrane-bound TH pools (35). Further studies will therefore be required to determine what portion of total TH interacts with VMAT2 and is membrane-bound as well as to understand the molecular determinants that modulate this association.

Likewise, although our results have identified three cytosolic domains of VMAT2 as involved in a direct interaction with TH, they do not exclude the involvement of other domains or additional proteins in this interaction. Indeed, it is plausible that scaffolding proteins, such as 14-3-3, may facilitate the organization of this VMAT2·AADC·TH complex at the vesicle surface (for a review, see Ref. 36). In fact, it has been demonstrated that TH is activated by forming a complex with 14-3-3 in a stimulus- and calmodulin kinase II-dependent manner (37). Another potential scaffolding molecule, α-synuclein, has structural homology with and binds to 14-3-3 proteins (38, 39). Several reports suggest that α-synuclein may affect DA homeostasis (16, 32, 40) and is capable of binding vesicles (41) as well as binding to and regulating both TH (32) and VMAT2 (42). Furthermore, a number of known mutations in α-synuclein have been implicated in familial forms of Parkinson disease (for a review, see Ref. 16). Further studies are needed to determine if these scaffolding proteins are required for assembly of the VMAT2·TH·AADC complex and how this complex is regulated.

On the other hand, the chaperone protein Hsc70 has been shown to associate with the vesicular transporter VGAT and the enzyme that synthesizes GABA, GAD65, in GABAergic synaptic vesicles (43). Specifically, VGAT was shown to interact with a number of different proteins, such as GAD65/67, Hsc70, calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II, and SV2 (43). Ultimately, the authors suggested that VGAT might be part of a multiprotein complex that functionally couples GABA synthesis and transport into synaptic vesicles (43). Indeed, we have recently reported an interaction between Hsc70 and VMAT2 (44). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that equivalent mechanisms to efficiently couple neurotransmitter synthesis and vesicle loading might have evolved in the DA pathway. Similarly, two enzymes required for DA synthesis, TH and GTP cyclohydrolase I, have been reported to be physically and functionally coupled in Drosophila (45). GTP cyclohydrolase I is an enzyme responsible for the synthesis of tetrahydrobiopterin, which is a necessary co-factor for the activity of TH, and the authors speculated that its association with TH leads to optimal catecholamine production. These examples illustrate that several processes that were once thought to occur independently are indeed physically and functionally coupled.

Although TH has been largely characterized as a soluble, cytoplasmic enzyme, a significant number of reports have indicated that this enzyme can also exist associated with SVs and LDCVs in neurons and adrenal chromaffin cells, respectively (46). Early electronic microscopy studies demonstrated that TH associates with synaptic vesicles in caudate nucleus (23). More recently, Tsudzuki and Tsujita (47) reported that in synaptic vesicles isolated from rat brain, TH co-purified with H+-ATPase, VMAT2, and the vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Accordingly, Kuczenski et al. (20) demonstrated that brain TH associated with membranes is functionally more active than soluble brain TH. On the other hand, in chromaffin granules, the membrane-bound TH appears to be present in a “detergent-labile” association with the granule membrane (21) and exposed to the cytoplasm (19). Additionally, Morita et al. (22) demonstrated that this association between TH and granule membranes is reversible and specific and that TH activity can be modulated through its association with the granule surface. Because TH can also be found in a soluble state, it is reasonable to assume that a shift of the enzyme from its soluble form to the membrane-associated form is accompanied by an increase of TH activity. Thus, our data support these previous studies documenting an association between TH and synaptic vesicles and add biochemical and functional evidence that link DA synthesis and vesicular storage.

This physical and functional coupling of DA synthesis and its transport into vesicles challenges the current accepted view that these two events occur independently. The traditional view suggests that DA synthesis occurs in the neuronal cytosol via hydroxylation of l-tyrosine by TH to form l-DOPA. Subsequently, l-DOPA is then decarboxylated by AADC to yield DA. Cytosolic DA can then be either packaged into vesicles by VMAT2 or metabolized by monoamine oxidase B (48, 49). Both of these pathways would ensure the maintenance of low levels of cytosolic DA, minimizing its potential toxic effects. Indeed, cytosolic concentrations of DA in substantia nigra cells are practically undetectable (50). Increased metabolism of DA leads to toxicity caused by the generation of reactive species, such as OH•, O2˙̄, H2O2, and neurotoxic quinines (42, 51–55). In fact, chronic exposure to cytosolic DA determines the progressive degeneration of DA-containing neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (49, 52). The significant loss of dopaminergic neurons results in a substantial deficiency of striatal dopamine, which is thought to lead to many of the clinical manifestations of Parkinson disease (16, 49, 55, 56). A physical and functional coupling between DA synthesis and vesicle loading as proposed by our study might limit DA increases to the local area surrounding the synaptic vesicle membrane. Therefore, DA would be transported more efficiently into the synaptic vesicle, minimizing its diffusion and potential oxidation and toxicity.

Our results might also have important implications in our understanding of synaptic vesicle refilling and the regulation of quantal size. Several studies have shown that the amount of DA stored in vesicles can be altered presynaptically (12, 57–59). As a result, the number of molecules released per synaptic vesicle exocytotic event, known as the quantal size (57), can be altered at different levels. For instance, VMAT2 overexpression, TH activation, and l-DOPA administration have been shown to increase quantal size in dopaminergic neurons. On the other hand, TH inhibition through D2-like dopamine autoreceptor activation reduces quantal size in PC12 cells (58). Interestingly, TH activation is dependent, at least in part, on the presence of granule membranes, and it has been suggested that the interaction of TH with the granule membranes might require additional proteins (19, 20). Our results suggest that VMAT2 might be at least one of the factors that determine the association of TH with granule membranes and its further activation. Regulation of the TH activity by association with vesicles though a protein complex with VMAT2 and AADC would be a mechanism that might ultimately determine regulation of the quantal size (49, 57, 59). Finally, our data are also consistent with a rapid and efficient mechanism for synaptic vesicle refilling during high frequency stimulation (60, 61). In this regard, the VMAT2·TH·AADC complex would efficiently and rapidly synthesize and load DA into the recycling vesicle going into a rapid cycle due to high neuronal activity.

In summary, our results demonstrate a functional and physical coupling between VMAT2, TH, and AADC and suggest an important role in the maintenance of low cytosolic DA levels, regulation of quantal size, and synaptic vesicle refilling. Further studies will be required to define the molecular details and regulatory mechanisms associated with these novel protein-protein interactions.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the kind gift of the pQE30 vector containing the His6-TH from Dr. Janis O'Donnell (University of Alabama). We are grateful to the members of the Torres and Amara laboratories for helpful discussions. We also thank Dr. Elias Aizeman for critical advice and Dr. Carl Lagenaur for help with the velocity gradient experiments.

Footnotes

- DA

- dopamine

- TH

- tyrosine hydroxylase

- AADC

- aromatic amino decarboxylase

- VMAT

- vesicular monoamine transporter

- LDCV

- large dense core vesicle

- SV

- synaptic vesicle

- GST

- glutathione S-transferase

- α-MPT

- α-methyl-p-tyrosine

- NSD 1015

- m-hydroxybenzylhydrazine

- NE

- norepinephrine

- 5-HT

- serotonin

- DOPA

- di-OH-phenylalanine

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- β-ME

- β-mercaptoethanol

- GABA

- γ-aminobutyric acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Zhou Q. Y., Palmiter R. D. (1995) Cell 83, 1197–1209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carlsson A. (2001) Science 294, 1021–1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vermetten E., Bremner J. D. (2002) Depress. Anxiety 15, 126–147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berridge C. W., Waterhouse B. D. (2003) Brain Res. Rev. 42, 33–84 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Michelsen K. A., Prickaerts J., Steinbusch H. W. (2008) Prog. Brain Res. 172, 233–264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Palmiter R. D. (2008) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1129, 35–46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y., Schweitzer E. S., Nirenberg M. J., Pickel V. M., Evans C. J., Edwards R. H. (1994) J. Cell Biol. 127, 1419–1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nirenberg M. J., Liu Y., Peter D., Edwards R. H., Pickel V. M. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 8773–8777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nirenberg M. J., Chan J., Liu Y., Edwards R. H., Pickel V. M. (1996) J. Neurosci. 16, 4135–4145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Erickson J. D., Schafer M. K., Bonner T. I., Eiden L. E., Weihe E. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 5166–5171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nirenberg M. J., Chan J., Liu Y., Edwards R. H., Pickel V. M. (1997) Synapse 26, 194–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edwards R. H. (2007) Neuron 55, 835–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y., Peter D., Roghani A., Schuldiner S., Privé G. G., Eisenberg D., Brecha N., Edwards R. H. (1992) Cell 70, 539–551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Erickson J. D., Eiden L. E., Hoffman B. J. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 10993–10997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peter D., Liu Y., Sternini C., de Giorgio R., Brecha N., Edwards R. H. (1995) J. Neurosci. 15, 6179–6188 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lotharius J., Brundin P. (2002) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 932–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zigmond R. E., Schwarzschild M. A., Rittenhouse A. R. (1989) Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 12, 415–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haycock J. W., Haycock D. A. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266, 5650–5657 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuhn D. M., Arthur R., Jr., Yoon H., Sankaran K. (1990) J. Biol. Chem. 265, 5780–5786 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuczenski R. T., Mandell A. J. (1972) J. Biol. Chem. 247, 3114–3122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelner K. L., Morita K., Rossen J. S., Pollard H. B. (1986) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 2998–3002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morita K., Teraoka K., Oka M. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 5654–5658 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fahn S., Rodman J. S., Côté L. J. (1969) J. Neurochem. 16, 1293–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagatsu T., Sudo Y., Nagatsu I. (1971) J. Neurochem. 18, 2179–2189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandell A. J., Knapp S., Kuczenski R. T., Segal D. S. (1972) Biochem. Pharm. 21, 2737–2750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pickel V. M., Joh T. H., Field P. M., Becker C. G., Reis D. J. (1975) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 23, 1–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pickel V. M., Joh T. H., Reis D. J. (1976) J. Histochem. Cytochem. 24, 792–806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christenson J. G., Dairman W., Udenfriend S. (1972) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 69, 343–347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Carneiro A. M., Ingram S. L., Beaulieu J. M., Sweeney A., Amara S. G., Thomas S. M., Caron M. G., Torres G. E. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 7045–7054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Funderburk C. D., Bowling K. M., Xu D., Huang Z., O'Donnell J. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33302–33312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morciano M., Burré J., Corvey C., Karas M., Zimmermann H., Volknandt W. (2005) J. Neurochem. 95, 1732–1745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perez R. G., Waymire J. C., Lin E., Liu J. J., Guo F., Zigmond M. J. (2002) J. Neurosci. 22, 3090–3099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reinhard J. F., Jr., Smith G. K., Nichol C. A. (1986) Life Sci. 39, 2185–2189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makinae K., Kobayashi T., Kobayashi T., Shinkawa H., Sakagami H., Kondo H., Tashiro F., Miyazaki J., Obata K., Tamura S., Yanagawa Y. (2000) J. Neurochem. 75, 1429–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang J., Lou H., Pedersen C. J., Smith A. D., Perez R. G. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 14011–14019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Obsilová V., Silhan J., Boura E., Teisinger J., Obsil T. (2008) Physiol. Res. 57, S11–S21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Itagaki C., Isobe T., Taoka M., Natsume T., Nomura N., Horigome T., Omata S., Ichinose H., Nagatsu T., Greene L. A., Ichimura T. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 15673–15680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ostrerova N., Petrucelli L., Farrer M., Mehta N., Choi P., Hardy J., Wolozin B. (1999) J. Neurosci. 19, 5782–5791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kleppe R., Toska K., Haavik J. (2001) J. Neurochem. 77, 1097–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mosharov E. V., Staal R. G., Bové J., Prou D., Hananiya A., Markov D., Poulsen N., Larsen K. E., Moore C. M., Troyer M. D., Edwards R. H., Przedborski S., Sulzer D. (2006) J. Neurosci. 26, 9304–9311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rochet J. C., Outeiro T. F., Conway K. A., Ding T. T., Volles M. J., Lashuel H. A., Bieganski R. M., Lindquist S. L., Lansbury P. T. (2004) J. Mol. Neurosci. 23, 23–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo J. T., Chen A. Q., Kong Q., Zhu H., Ma C. M., Qin C. (2008) Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 28, 35–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jin H., Wu H., Osterhaus G., Wei J., Davis K., Sha D., Floor E., Hsu C. C., Kopke R. D., Wu J. Y. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4293–4298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Requena D. F., Parra L. A., Baust T. B., Quiroz M., Leak R. K., Garcia-Olivares J., Torres G. E. (2009) J. Neurochem. 110, 581–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bowling K. M., Huang Z., Xu D., Ferdousy F., Funderburk C. D., Karnik N., Neckameyer W., O'Donnell J. M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 31449–31459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nagatsu T., Nagatsu I. (1970) Experientia 26, 722–723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tsudzuki T., Tsujita M. (2004) J. Biochem. 136, 239–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Berry M. D., Juorio A. V., Paterson I. A. (1994) Prog. Neurobiol. 42, 375–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Caudle W. M., Colebrooke R. E., Emson P. C., Miller G. W. (2008) Trends Neurosci. 31, 303–308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mosharov E. V., Larsen K. E., Kanter E., Phillips K. A., Wilson K., Schmitz Y., Krantz D. E., Kobayashi K., Edwards R. H., Sulzer D. (2009) Neuron 62, 218–229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hastings T. G., Lewis D. A., Zigmond M. J. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 1956–1961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hastings T. G., Lewis D. A., Zigmond M. J. (1996) Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 387, 97–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sulzer D., Bogulavsky J., Larsen K. E., Behr G., Karatekin E., Kleinman M. H., Turro N., Krantz D., Edwards R. H., Greene L. A., Zecca L. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 11869–11874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen R., Wei J., Fowler S. C., Wu J. Y. (2003) J. Biomed. Sci. 10, 774–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caudle W. M., Richardson J. R., Wang M. Z., Taylor T. N., Guillot T. S., McCormack A. L., Colebrooke R. E., Di Monte D. A., Emson P. C., Miller G. W. (2007) J. Neurosci. 27, 8138–8148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen L., Ding Y., Cagniard B., Van Laar A. D., Mortimer A., Chi W., Hastings T. G., Kang U. J., Zhuang X. (2008) J. Neurosci. 28, 425–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Reimer R. J., Fon E. A., Edwards R. H. (1998) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 8, 405–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pothos E. N., Davila V., Sulzer D. (1998) J. Neurosci. 18, 4106–4118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pothos E. N., Larsen K. E., Krantz D. E., Liu Y., Haycock J. W., Setlik W., Gershon M. D., Edwards R. H., Sulzer D. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 7297–7306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Scherman D. (1986) J. Neurochem. 47, 331–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Scherman D., Boschi G. (1988) Neuroscience 27, 1029–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]