Abstract

Bisphosphonates (BPs) are potent inhibitors of osteoclast function, widely used to treat excessive bone resorption associated with bone metastases, that also have anti-tumor activity. Zoledronic acid (ZOL) represents a potential chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of cancer. ZOL is the most potent nitrogen-containing BPs, and it inhibits cell growth and induces apoptosis in a variety of cancer cells. Recently we demonstrated that accumulation of isopentenyl pyrophosphate and the consequent formation of a new type of ATP analog (ApppI) after mevalonate pathway inhibition by nitrogen-containing BPs strongly correlates with ZOL-induced cell death in cancer cells in vitro. In this study we show that ZOL-induced apoptosis in HF28RA human follicular lymphoma cells occurs exclusively via the mitochondrial pathway, involves lysosomes, and is dependent on mevalonate pathway inhibition. To define the exact signaling pathway connecting them, we used modified HF28RA cell lines overexpressing either BclXL or dominant-negative caspase-9. In both mutant cells, mitochondrial and lysosomal membrane permeabilization (MMP and LMP) were totally prevented, indicating signaling between lysosomes and mitochondria and, additionally, an amplification loop for MMP and/or LMP regulated by caspase-9 in association with farnesyl pyrophosphate synthetase inhibition. Additionally, the lysosomal pathway in ZOL-induced apoptosis plays an additional/amplification role of the intrinsic pathway independently of caspase-3 activation. Moreover, we show a potential regulation by Bcl-XL and caspase-9 on cell cycle regulators of S-phase. Our findings provide a molecular basis for new strategies concomitantly targeting cell death pathways from multiple sites.

Introduction

Bisphosphonates are pyrophosphate analogs that are highly effective inhibitors of bone resorption (1) and, thus, are widely used in the treatment of skeletal diseases associated with high osteoclast activity and accelerated bone turnover, such as osteoporosis (2) and Paget disease (3). Furthermore, bisphosphonates are effective inhibitors of tumor-induced bone resorption and have been shown to modify the progression of skeletal metastasis in several forms of cancer, especially breast cancer and myeloma (4). Considerable preclinical evidence indicates that bisphosphonates, especially zoledronic acid (ZOL),3 have anti-tumor activity in vitro and in vivo (5). Recently in a clinical study ZOL together with adjuvant endocrine therapy improved disease-free survival in premenopausal patients with estrogen-responsive early breast cancer (6). There are not in vivo data on the ZOL concentration in tumor tissue after various treatments in vivo, but these outcomes strongly suggest that bisphosphonates may have a direct effect on cancer cells.

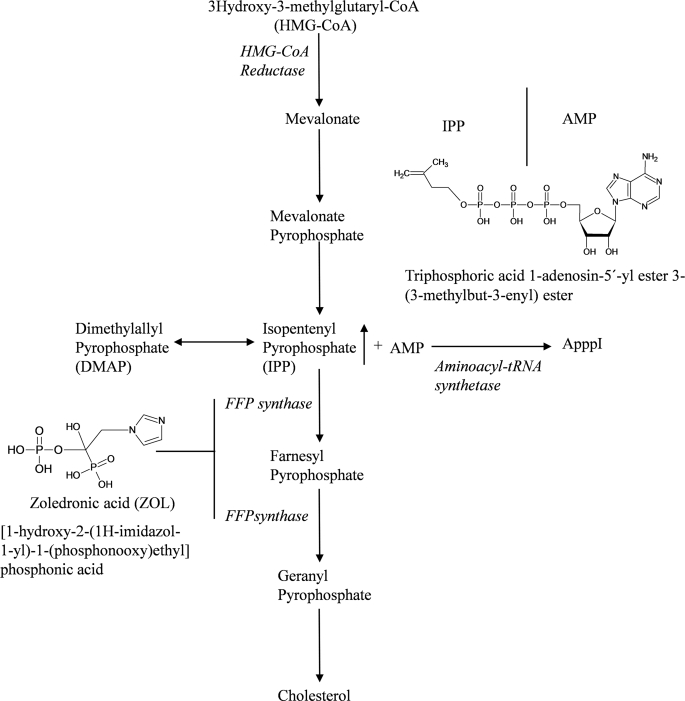

The anti-tumor activity of ZOL has been linked to its capacity to induce apoptosis in various tumor cell lines (4, 7) and to reduce tumor cell migration, invasion, adhesion, proliferation, and angiogenesis (8). Nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates, including ZOL, act by inhibiting farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) synthase, one of the key enzymes of the intracellular mevalonate pathway (9). This leads to a block in the production of the isoprenoid lipids, FPP, and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (Fig. 1) followed by loss of prenylated small signaling proteins (Rho, Ras) (10) and, consequently, apoptosis (11, 12). This is the widely accepted molecular mechanism for nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates to inhibit osteoclast activity and bone resorption (13). We showed recently, however, that the inhibition of FPP synthase leads also to the accumulation of a pathway intermediate, isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP). IPP becomes conjugated to AMP to form a novel ATP analogue (ApppI) (Fig. 1). This cytotoxic ATP analog formed in the cells is able to inhibit mitochondrial adenine nucleotide translocase in a cell-free system, which is a plausible additional mechanism for bisphosphonate-induced apoptosis (14). We showed also that ZOL-induced IPP/ApppI formations as well as the inhibition of protein prenylation, both outcomes of FPP synthase inhibition in mevalonate pathway, act in concert in ZOL-induced apoptosis in cancer cells (15). However, the exact mechanisms and mediators of ZOL-induced apoptosis are currently unknown.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of mevalonate pathway and ApppI synthesis. Zoledronic acid acts by inhibiting FPP synthase. The mevalonate pathway is blocked, and the accumulation of IPP consequently occurs. Furthermore, IPP is conjugated to AMP to form a novel ATP analogue, ApppI.

ZOL has been shown to cause disruption of survival pathways associated with the translocation of unprenylated Ras and RhoA from the cell membrane to the cytosol (16). This leads to the inhibition of the Ras/Raf1/MEK (mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase)/ERK1/2 (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2) mitogenic pathway (16) and anti-apoptotic protein kinase B/Akt (16, 17), causing caspase-9 activation (17). In response to ZOL, the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is also affected (18). Additionally, c-Jun N-terminal kinase, Rock, and focal adhesion kinases were identified to be perturbed by ZOL in a prenylation-dependent manner (16).

Concerning the initiation of the apoptotic signaling pathways by ZOL, a classical mitochondrial pathway was described to be regulated by Bcl-2 family protein members (11, 12) and involving cytochrome c release (12), caspase-3 (18), caspase-7 (12, 19), and caspase-9 (12) activation. Additionally, mitochondria participate in amplifying the ZOL-induced death signal from caspase-8, activated through the extrinsic pathway in colon carcinoma cells (12). Recently, new mediators of ZOL-induced cell death, such as apoptosis-inducing factor (11, 12) and endonuclease G (11), without further caspase activation have been described. Interestingly, anoikis (20) and necrosis (21) have been proposed as alternative cell death mechanisms. Despite the emerging data on ZOL-induced programmed cell death, its molecular mediators still remain under debate.

In a simplistic view, there are two major pathways that promote apoptosis in mammalian cells. The extrinsic pathway is initiated by death receptor superfamily members and leads to caspase-8 activation (22). Consequently, caspase-3 or other effector caspases (caspase-6 and -7) are processed depending on the cell type; that is, type I cells, where downstream caspases are activated directly through caspase-8, and type II cells, where the signal needs to be amplified via mitochondria-dependent apoptotic pathways by cleavage of pro-apoptotic Bid (23). The intrinsic pathway is triggered by different stress signals mainly at the mitochondrial level and is characterized by assembly of cytosolic apoptotic protease activating factor 1 and cytochrome c with subsequent activation of caspase-9 (24). Therefore, biochemical and morphological changes, including cellular shrinkage, chromatin condensation, and DNA fragmentation are almost invariably involved in both pathways.

Mitochondria are considered to orchestrate apoptosis, that being the center for the cysteine protease-induced cell death (25) and also for other apoptotic pathways (26). Additionally, it has been proposed that MMP might represent the point of no return of the lethal stressors-induced signal (27, 28), where Bcl-2-related proteins (pro- and anti-apoptotic) control this phenomenon (29, 30). Moreover, anti-apoptotic members of the Bcl-2 family (such as Bcl-2 and BclXL), which reside mainly but not exclusively in the outer mitochondrial membrane, are endowed with the capacity to inhibit apoptosis at least in part by locally preventing MMP loss (28, 31).

Lysosomes have been revealed to have increasing importance in the mechanism of apoptosis, with cross-talk between lysosomes and mitochondria in apoptosis pathways (25). The hallmark of lysosomal damage, often associated with LMP, can induce the release of cathepsins (cysteine protease) into the cytosol, which are implicated in a controlled mode of cell death (32). There is strong evidence that lysosomal breakdown occurs before MMP via phospholipase A2 release and subsequent reactive oxygen species production from mitochondria (33). Lysosomal proteases, cathepsins, can indirectly activate caspases via lysoapoptases. Lysoapoptases activated by cathepsins within the lysosomal compartment are finally translocated to the cytosol where they can activate pro caspase-3 (34). Bid activation provides further evidence that lysosomes precede MMP in the apoptotic pathway (35), as the tBid fragment produced by cathepsins is translocated to mitochondria and induces further cellular demise (36). On the other hand, many outcomes suggest that lysosomal rupture occurs downstream from MMP and is a consequence of oxidative stress of mitochondrial origin. Thus, there seems to be an amplification loop with further lysosomal rupture and enhanced mitochondrial damage (37). However, some data suggest that lysosomal breakdown and consequent cathepsins release might trigger cell death via a MMP-independent pathway with direct effects of cathepsins on the nucleus (38). Overall, it seems that the temporal order is strongly dependent on the cell type and experimental conditions used. Additionally, cells may have many different mechanisms and pathways on their way to death.

The aim of this study was to further identify the apoptotic pathways involved in ZOL-induced cell death. The data indicate that ZOL induces cell apoptosis in the follicular lymphoma (HF28RA) cell line exclusively through the mitochondrial pathway, where caspase-9 and lysosomes have additional/amplification role.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

ZOL was kindly provided by Novartis Pharma AG (Basel, Switzerland) as the hydrated disodium salt (Mr 401.6). A stock solution of ZOL was prepared in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4; Invitrogen), filter-sterilized, and stored at −20 °C until use. Geranylgeraniol (GGOH), pan-caspase inhibitor (z-VAD-fmk), and cathepsin inhibitor (E64) were purchased from Sigma. Stock solutions of GGOH and E64 were prepared in pure ethanol, whereas z-VAD-fmk was prepared in DMSO (Sigma). All compounds were diluted in cell culture medium to the desired concentration immediately before use. The final concentration of ethanol/DMSO in culture media did not exceed 0.1% (v/v), and no alteration in cell growth was observed in vehicle controls. ApppI was synthesized as previously described (14). IPP, AppCp, and sodium orthovanadate were purchased from Sigma. Sodium fluoride was from Riedel-de-Haën.

Cell Culture

Human follicular lymphoma cell line HF28RA (wild type), vector control cells (HF28RA GFP), and modified cells overexpressing either Bcl-XL or dominant negative caspase-9 (DN-9) were from the Department of Microbiology, Institute of Clinical Medicine, Kuopio, Finland. The modified cell lines have been described in detail previously (39). All the cell lines were cultured in 100-ml (75 cm3) cell culture vent/closed flasks (Nunc, Roskilde Denmark) in RPMI 1640 medium (Cambrex Bio Science, BioWhittaker, Verbiers, Belgium) supplemented with 5% heat inactivated fetal calf serum (Invitrogen), 2 mm l-glutamine (Lonza, BioWhittaker), 10 mm HEPES (Lonza), 1 mm sodium pyruvate (Lonza), 0.1 mm nonessential amino acid (Lonza), 20 μm 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), and 100 units/ml penicillin-streptomycin (Lonza). All cell cultures were maintained at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified atmosphere.

Flow Cytometric Analysis of Apoptosis

1 × 106 cells were seeded in 25-cm3 flasks with vented caps (Nunc) at a density of 0.2 × 106 cells/ml. The cells were then treated with 25–100 μm ZOL alone or in combination with 10 μm GGOH for different time intervals up to 3 days. GGOH was found not to affect the viability and cell death at the used concentration. HF28RA cells were treated with ZOL alone (at the concentrations indicated) or after pretreatment with z-VAD-fmk (15–60 μm) or E64 (25–100 μm) for 2 h. The control cells were incubated according to an identical protocol with the corresponding amount of PBS (pH 7.4; Invitrogen), ethanol, or DMSO (Sigma). Results are representative of at least three independent experiments yielding similar results, or they are expressed as the mean ± S.E. from three independent experiments made in triplicate. Flow cytometry data were acquisitioned using a FACSCanto II Flow Cytometer (BD Biosciences) running under the DIVA software (Version 6.1.1).

Changes in mitochondrial function-induced by different apoptotic stimuli are associated with the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) (28) and are used in this study as a marker for MMP. The effects of different treatments on ΔΨm were analyzed in intact cells with the monovalent cationic fluorescent dye tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester (TMRM) (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) as previously described (40).

The analysis of DNA content was performed as previously described (41). Briefly, control and ZOL-treated cells were collected and washed with ice-cold PBS buffer, pH 7.4. Cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) were fixed with ice-cold ethanol (70% v/v) overnight, and incubated for 1 h at 56 °C with 10 μg/ml RNase (Sigma). Propidium iodide (Molecular Probes) was added to the final concentration of 5 μg/ml, and incubation was continued for 2 h at 37 °C. 10,000 events per condition were collected for each histogram.

Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization

Using the lysosomotropic base and metachromatic fluorochrome acridine orange (AO), a red fluorescence is exhibited when it is highly concentrated at acidic pH in lysosomes, and a green fluorescence is exhibited at low concentration in cytosol and nucleus. Lysosomal membrane destabilization may be monitored as a decrease in granular red fluorescence or as an increase in cytoplasmic diffuse green fluorescence as described previously (42). Accumulation of AO inside lysosomes was expressed as the percentage of cells with damaged organelles. Living cells (2 × 105) were stained with AO (0.005 μg/ml, 6 min at 37 °C without CO2, Molecular Probes). Immediately after staining, flow cytometer measurements were performed, and 5000 events per condition were collected for each histogram.

Activation of caspase-3 was examined with the caspase-3 Intracellular Activity Assay Kit II (PhiPhiLux® G2D2, Calbiochem) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the final incubation mixture containing 5 × 105 control or treated cells, 50 μl of 10 mm substrate solution, 20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, and 10% fetal bovine serum was incubated for 1 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2. The acquisition was performed in the FL2 channel of the flow cytometer.

Plasma membrane permeabilization was assessed using propidium iodide (5 μg/ml, Pharmingen). Briefly, control and ZOL-treated cells were collected, washed with cold PBS, and stained for 20 min at room temperature. Flow cytometer measurements were performed within 1 h.

Fluorescent microscopy was used to assess morphological changes. Control and ZOL-treated cells were washed with cold culture media and followed by Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes) staining (1.5 μg/ml) for 20 min at room temperature. Imaging was carried out with an Olympus AX70 Provis microscope equipped with FVII digital camera (Olympus Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and a 100-watt mercury burner as an epifluorescent light source. 40× and 60× air objective lenses and appropriate fluorescence mirror units (excitation/emission for Hoechst 33342 355/465 nm) were used to collect the images. The digital images were assembled using Adobe Photoshop.

Western Blots

15 × 106 control and ZOL-treated cells in the presence or absence of specified inhibitors were resuspended in 1.3 ml lysis buffer (Mammalian Cell Lysis kit, Sigma), and protein was isolated and post-conserved according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein content was quantified with the Bio-Rad Dc Protein assay kit and equalized, then samples were diluted in 4× Laemmli buffer (250 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 8% SDS (w/v), 20%, 2-mercaptoethanol, 40% glycerol (v/v), 0.004% bromphenol blue w/v) and boiled for 5 min. 20 μg of protein was separated by 11–15% SDS-PAGE and electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Amersham Biosciences Hybond-P PVDF membrane). A pre-stained Protein Marker (New England Biolabs (UK) Ltd.) with a broad range (6–175 kDa) was used as the molecular weight control marker. Unspecific binding sites on the polyvinylidene fluoride membrane were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or 5% milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS; 0.1% Tween 20, Sigma) for 1.30 h at room temperature for caspase-3 (3% BSA in TBS), 1 h at room temperature for caspase-8 (3% BSA in TBS) and Bid (5% milk in TBS), and overnight at 4 °C for UnRap1A and actin (5% milk in TBS). The following primary antibodies were used: mouse anti-β-actin (1:1000), goat anti-Rap1A (1:200), rabbit anti- caspase-3 (1:500) (from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.); mouse anti-caspase-8 (1:1000) and mouse anti-Bid (1:1000) (from Cell Signaling Technology®, Danvers, MA). The corresponding peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were from Zymed Laboratories Inc. (San Francisco, CA, USA) or GE Healthcare. Immunodetection was performed with Amersham Biosciences™ ECL™ Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare), and the blots were scanned with ImageQuant™-RT ECL (Version 1.0.1, GE Healthcare) running under I. Quant Capture-RT ECL software for Windows (Version 1.0.4.1, 1993–2006). Digitized pictures were adjusted with ImageJ software (Version 1.4.3, 1993–2006, Broken Symmetry Soft, freely available at rsb.info.nih.gov). Densitometry analyses were carried out using the same software and normalized by the internal control (actin).

Determination of Cytochrome c Release

Mitochondrial and cytosolic extracts were prepared using the ApoAlert cell fractionation kit (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal loading of mitochondria and cytosol was assessed by immunoblotting with anti-cytochrome c (1:1000) from Clontech. Cytosolic versus mitochondrial fraction purity was assessed by distribution of cytochrome oxidase subunit IV.

Mass Spectrometry Analysis of IPP/ApppI

For IPP/ApppI analysis, the cells treated with ZOL in combination with GGOH were scraped off the flasks and washed in ice-cold PBS. Extracts were prepared using ice-cold acetonitrile as previously described (14). For analysis, the evaporated cell extracts were redissolved in 150 μl of water containing 1 μm internal standard (AppCp) to compensate for the variability in ionization and 0.25 mm phosphatase inhibitors (sodium fluoride and sodium orthovanadate) to prevent the degradation of ApppI. The molar amounts of IPP and ApppI in the cell extracts were determined by HPLC negative ion electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-MS) as previously described (14). Detection was performed by a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer (Agilent 6410 Triple Quad LC/MS). Selected reaction monitoring was used for analysis of the compounds in the sample, and quantitation was based on the fragment ions characteristic to each molecule. The following transitions were monitored: m/z 245 → 159 for IPP, m/z 574 → 408 for ApppI, and, m/z 504 → 406 for the internal standard. The fragmentation pattern for each sample was compared with that of the authentic standard. Standards were constructed by spiking extracts from untreated cells with synthetic IPP or ApppI. Quantitation was done with Agilent Technologies MassHunter Work Station Software for Triple Quad Version B.01.03 (Thermo Finnigan) using the standard curve and the transitions mentioned above. Results shown are representative of at least three independent experiments (mean ± S.E.) unless stated otherwise.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as mean values ± S.E. and analyzed by ANOVA with the Bonferroni post-test using GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA) Version 4.03 for Windows; p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

ZOL-induced IPP/ApppI Formation and Apoptosis in HF28RA Cells

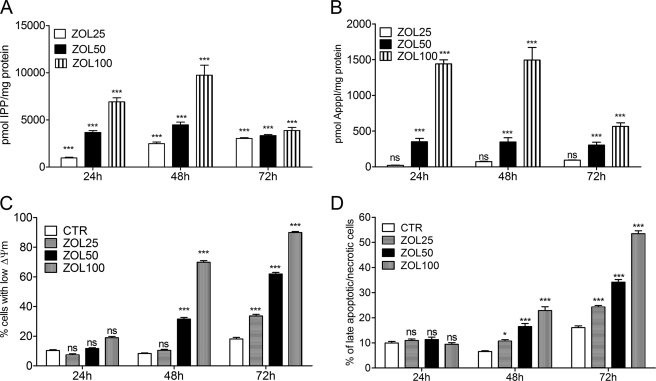

To determine the optimum conditions for the analysis of the apoptosis-inducing effects of ZOL, we incubated HF28RA cells with different concentrations of the drug for various times up to 72 h. ZOL exposure (25–100 μm) induced IPP (Fig. 2A) and ApppI (Fig. 2B) accumulation in HF28RA cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Flow cytometric analysis revealed that HF28RA cells cultured in the presence of ZOL (25–100 μm) underwent MMP, detected by the decrease of Δψm and measured as a reduction of TMRM incorporation (Fig. 2C). Cell membrane integrity (measured by propidium iodide assay) was also lost (Fig. 2D) in a dose and time-dependent manner. Thus, HF28RA cells accumulated IPP and ApppI after ZOL treatment and were sensitive to ZOL-induced apoptosis. The optimal concentration of ZOL to study apoptosis in this cell line was found to be 50 μm, and this concentration was used in all subsequent experiments.

FIGURE 2.

Kinetics of ZOL-induced IPP/ApppI formation and apoptosis. HF28RA cells were treated with 25–100 μm ZOL for different time intervals up to 3 days. The molar amount of IPP and ApppI was determined in cell extracts by HPLC-ESI-MS using 1 μm AppCp as the internal standard. A, shown is IPP accumulation. B, shown is ApppI production in the HF28RA cell line. C, shown are the effects on the mitochondrial transmembrane potential, ΔΨm, evoked by the indicated concentrations of ZOL determined by cytofluorimetry using TMRM staining. CTR, control. D, cell membrane integrity (late apoptosis/necrosis) assessed by flow cytometry using propidium iodide is shown. 5000 events per condition were collected for each histogram. The data are presented as the mean ± S.E. from 3–5 independent experiments. The statistical significance of the differences was determined using the ANOVA test with the Bonferroni post-test; ns, not significant (p > 0.05); p < 0.05 (*) and p < 0.001 (***) versus control.

ZOL-induced Death Signaling Is Mediated through the Mitochondrial Pathway

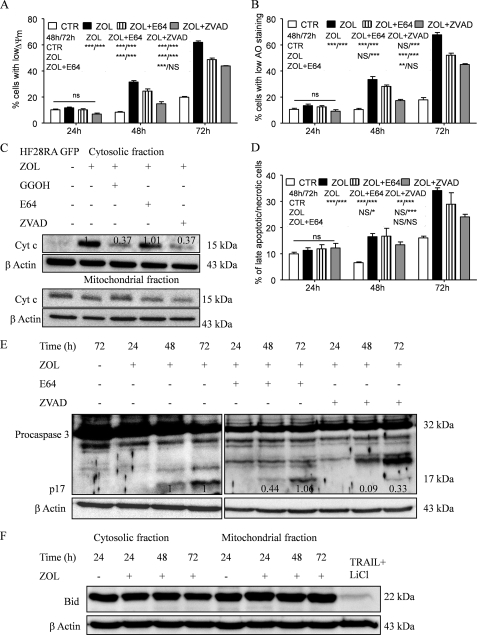

To elucidate the different pathways involved in the apoptotic process induced by ZOL, we used the HF28RA cell lines transfected with GFP, BclXL, and DN caspase-9 constructs. After treatment with 50 μm ZOL for up to 3 days, TMRM staining in GFP HF28RA cells indicated a significant increase in the loss of Δψm (Fig. 3A) and cell membrane permeabilization (using propidium iodide) (Fig. 3B) at 48 and 72 h, whereas no changes occurred after 24 h of treatment. HF28RA cells overexpressing BclXL or DN caspase-9 were significantly more resistant to ZOL-induced apoptosis than control vector cells, as seen both in MMP (Fig. 3A) and membrane integrity (Fig. 3B) assays. BclXL overexpression provided somewhat higher resistance to ZOL than DN caspase-9 modification, especially in terms of MMP at long exposure times (72 h).

FIGURE 3.

ZOL-induced death signaling is mediated through the mitochondrial pathway. HF28RA control (GFP, CTR), BclXL, and DN caspase-9-overexpressing cells were treated with 50 μm ZOL for various times (0–72 h). Mitochondrial membrane potential (A) and cell membrane integrity (B) were measured by flow cytometry; 5000 events per condition were collected for each histogram. The data are presented as the mean ± S.E. from 3–8 independent experiments. ns, not significant (p > 0.05); p < 0.01 (**) and p < 0.001 (***) versus corresponding ZOL treatment effects on HF28RA GFP cells; p < 0.05 (□) and p < 0.001 (□□□) when compared ZOL exposure effects on MMP or membrane integrity of HF28RA BclXL versus ZOL exposure effects on HF28RA DN9 cells. C, time course of cytochrome c (Cyt c) expression in HF28RA cells by Western blot in control (HF28RA GFP)-, BclXL-, and DN caspase-9-modified constructs. Cytochrome oxidase subunit IV (COXIV) was used as a control for enrichment quality, and β-actin was used as a control for equal protein loading. One representative experiment from three is depicted. D, shown is caspase-3 status in apoptotic and non-apoptotic cell lysates. HF28RA cells were left untreated (lane 1) or were treated with ZOL 50 μm for the indicated times (lanes 2–4) to induce apoptosis. Western blot analysis using polyclonal caspase-3 antibodies (recognizing both pro- and active caspase-3) shows that procaspase-3 (32 kDa) is present in both untreated and apoptotic lysates, but active caspase-3 (17 kDa) is present only in apoptotic lysates of control vector/GFP cells, whereas no active fragment could be seen at any exposure time point in BclXL- and DN9-overexpressing cell lines. Three independent experiments yielded similar results. E, shown is PhiPhiLux flow cytometric analysis of caspase-3-like activity in intact cells undergoing apoptosis. GFP, BclXL, and DN caspase-9 HF28RA cells were left untreated (CTR) or treated for 72 h with ZOL to induce apoptosis. Cells were stained with G2D2-conjugated PhiPhiLux. Numbers indicate the percentage of cells with activated caspase-3. Histograms were assembled into three-dimensional plots using WinMDI 2.8 software. A study representative of two is shown. F, shown is caspase-8 expression after 50 μm ZOL exposure for different time intervals. Procaspase-8 was identified as a band of 55/53 kDa, and the cleaved caspase-8 was identified at 43/41 and 18 kDa. As positive control we used an extract from TRAIL + LiCl-treated HF28RA wild type cells. Similar data were obtained in another independent study.

After exposure to an apoptotic stimulus, cytochrome c is released into the cytosol, an event that may be required for the completion of apoptosis in some systems (44). However, it has been shown that release of cytochrome c could be independent of mitochondrial depolarization (45). In HF28RA cells, as a consequence of the decrease of Δψm, ZOL induced a substantial release of cytochrome c from mitochondria into the cytosol in vector control cells, whereas it was completely blocked in BclXL and DN caspase-9-overexpressing cells (Fig. 3C).

ZOL also caused proteolytic maturation of caspase-3 in GFP cells, whereas in BclXL and DN9 cells caspase-3 activation was not detected, as determined by immunoblots (Fig. 3D) and by cleavage of the cell-permeable substrate PhiPhiLux G2D2 (Fig. 3E) (46). Untreated cells were primarily negative for the presence of active caspase-3, whereas 28% of control cells treated with ZOL had detectable active caspase-3 after 72 h of exposure. HF28RA BclXL and HF28RA DN9 cells displayed 8.3 and 10% of caspase-3-positive cells after 72 h of exposure to ZOL, respectively. Our data also indicate that flow cytometric analysis is more sensitive than Western blot to explore caspase-3 activation. Because caspase-8 could also be activated as a postmitochondrial event (47), the effect of ZOL treatment on the cleavage of full-length caspase-8 was studied in HF28RA GFP cells, with no sign of activation (Fig. 3F).

The cell cycle specificity of ZOL in HF28RA cells was studied employing cell cycle analysis. ZOL inhibited cellular growth of HF28RA control cells via a significant S cell cycle arrest followed by apoptosis (Fig. 4A). Transient lengthening of S-phase of cell cycle by ZOL is in line with previous studies on osteosarcoma (11), leukemia (48), and neuroblastoma (19) cells. Interestingly, BclXL and DN caspase-9 overexpression was able to prevent cell cycle progression to subG1 phase, i.e. apoptosis, and block the cells in S-phase (Fig. 4A). Typical apoptotic morphology, including chromatin condensation, nuclear fragmentation, and cell shrinkage was observed only in the HF28RA GFP cell line using Hoechst staining, whereas again, overexpression of Bcl-XL and DN caspase-9 abolished these apoptotic features (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

BclXL and DN caspase-9 block cell cycle-progression in S phase and subsequent chromatin condensation in HF28RA cells. A, analysis of the nuclear DNA content upon treatment with ZOL is shown. Cell cycle distributions of HF28RA control GFP-, BclXL-, and DN caspase-9-modified cell lines treated or not with 50 μm ZOL for up to 72 h were analyzed by propidium iodide staining and fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. G0-G1, G2-M, and S indicate the cell phase, and sub-G1 DNA content refers to the percentage of apoptotic cells. 10,000 events per condition were collected for each histogram. A study representative of three is shown. B, at the end of the experiment cells were stained with Hoechst 33342 and photographed under UV illumination.

Taken together, these results suggest that the mitochondrial-dependent pathway represents the major step required for complete activation of caspase-3 and apoptosis induced by ZOL in lymphoma cells. Overexpression of Bcl-XL and DN caspase-9 render the cells resistant for ZOL-induced apoptosis.

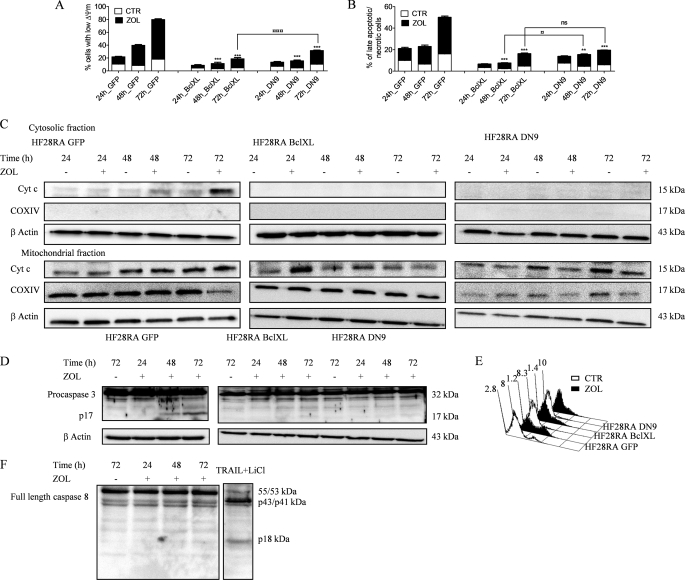

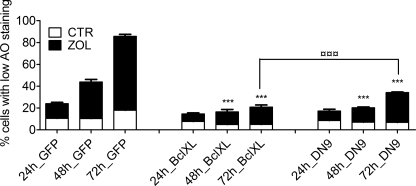

LMP Loss in ZOL-induced Apoptosis Is Regulated by BclXL and Caspase-9

ZOL caused a progressive decline in the red staining of lysosomes with AO in HF28RA GFP cells (Fig. 5), suggesting the involvement of these organelles in the apoptotic process. Additionally, the number of cells with significantly damaged lysosomes correlated with the number of cells with decreased Δψm (Fig. 3A). Transfection of the cells with BclXL or DN caspase-9 completely blocked LMP in the presence of ZOL (p < 0.001, ZOL effects on LMP of transfected cell lines versus the corresponding ZOL treatment effects on GFP HF28RA cells). After 72 h of incubation, DN caspase-9-transfected cells were less resistant to LMP upon ZOL treatment than BclXL-overexpressing cells (26.8 versus 12.8%, p < 0.001, Fig. 5), again displaying a pattern identical to that seen on MMP (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 5.

LMP loss in ZOL-induced apoptosis of HF28RA cells is regulated by BclXL and caspase-9. Cells were exposed to 50 μm ZOL for the times indicated, and lysosomal stability was assessed using the acridine orange uptake method. Results are expressed as the percent of cells with low AO staining and are representative of a minimum of three independent determinations. Data are expressed as the mean values ± S.E. (n = 3–6) and analyzed by two way ANOVA with the Bonferroni post-test. ***, p < 0.001 versus corresponding ZOL treatment effects on LMP of HF28RA GFP cells; □□□, p < 0.001 for the comparison of ZOL exposure effects on LMP of HF28RA BclXL versus ZOL exposure effects on HF28RA DN9 cells. CTL, control.

Effect of Caspase/Cathepsin Inhibitors on ZOL-induced Apoptosis in HF28RA Cells

To determine the relative contribution of caspases to ZOL-induced apoptosis, we employed caspase inhibitors. Pretreatment for 2 h with a pan-caspase inhibitor z-VAD-fmk at 60 μm, a dose that efficiently blocked caspase-3 activation in HF28RA control vector cells (Fig. 6E), significantly blocked the MMP (Fig. 6A), mitochondrial cytochrome c release (Fig. 6C), and cell membrane permeabilization (Fig. 6D), confirming the involvement of caspases in ZOL-induced apoptosis. However, inhibition was not complete, suggesting the existence of additional mechanisms.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of caspase/cathepsin inhibitors on ZOL-induced apoptosis in HF28RA cells. Inhibition of ZOL-induced apoptosis of the follicular lymphoma cell line was estimated in co-culture with the pancaspase inhibitor z-VAD and the cathepsin B/L inhibitor, E64. Cells were preincubated (2 h) with each inhibitor (60 μm for z-VAD-fmk, 100 μm for E64) and then exposed for up to 72 h to 50 μm ZOL. z-VAD-fmk and E64 alone did not have any effect on the proliferation of HF28RA cells (data not shown). Detection of Δψm reduction (A), lysosomal membrane permeabilization (B), and cell membrane integrity (D) was measured by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. Statistical evaluation of the data were performed using the ANOVA test; NS, not significant (p > 0.05); p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***) when compared with control and ZOL and ZOL+E64-treated cells versus corresponding treatment effects, as depicted in the data underneath the legends, on MMP, LMP, and membrane integrity, respectively. CTL, control. C, effects of caspase/cathepsin inhibitors and GGOH on ZOL-induced cytochrome c (Cyt c) release in HF28RA cells. Cells were preincubated (2 h) with caspase/cathepsin inhibitor (60 μm for z-VAD-FMK, 100 μm for E64) or directly co-incubated with geranylgeranyl (10 μm GGOH) before being exposed to 50 μm ZOL for 72 h. Cytochrome c expression was monitored by Western blot and followed by densitometric analysis normalized by the internal control (β-actin) and relative to the respective cytochrome c level from cells exposed to ZOL alone for 72 h, which was set to 1. E, shown is a Western blot analysis of caspase-3 cleavage. Equal loading was controlled by immunodetection of β-actin. Numbers underneath the bands represent densitometric analysis normalized to β-actin and relative to the corresponding levels of the 17-kDa caspase-3-activated fragment from ZOL-alone-treated cells, which was set to 1. F, time course of full-length Bid expression (22 kDa) in HF28RA GFP cells treated with 50 μm ZOL. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) obtained after fractionation of cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE on 15% gels. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Bid was detected as a 22-kDa protein. As a positive control we used an extract from TRAIL + LiCl-treated HF28RA wild type cells where full-length Bid expression decreased. Two independent experiments yielded comparable results.

To further investigate the cross-talk between caspases and lysosome-induced apoptosis, we measured LMP after co-treatment with ZOL and z-VAD-fmk. Interestingly, the inhibitory effect of z-VAD-fmk on ZOL-induced LMP (Fig. 6B) was identical to that of MMP (Fig. 6A). This suggests that caspases are involved at least in part in lysosomal destabilization but also that the protection of lysosomes might be a consequence of the protection of mitochondria mediated by this inhibitor. The inhibition of LMP along with MMP by z-VAD-fmk was previously reported in human B lymphoma and the U937 cell line upon camptothecin exposure (49).

In most cell systems LMP is associated with the cytosolic release of cathepsins (32). To further study the mechanism of lysosomal apoptosis upon ZOL exposure, the ability of E64, a papain-like cysteine protease inhibitor, to inhibit apoptosis was studied. Protection against ZOL-induced apoptosis was conferred by a 2-h preincubation with 100 μm E64, whereas lower concentrations (15–50 μm) were not able to significantly inhibit cell death (data not shown). This result suggests involvement of cysteine cathepsins in the process. Protection was significant at both the MMP (Fig. 6A) and LMP levels (Fig. 6B) but, again, incomplete. This outcome suggests that cathepsins are involved in part in the Δψm loss, and consequently, their activation is associated with amplification of the mitochondrial death signal. Secondly, activated cathepsins can act as an amplification loop for further LMP. However, LMP inhibition could also be a consequence of MMP inhibition. The inhibitory effect of E64 on MMP is not sufficient to inhibit cytochrome c release from mitochondria (Fig. 6C) and subsequent proteolytic maturation of caspase-3 at 72 h, as shown by the presence of activated fragment from 17 kDa (Fig. 6E). Additionally, E64 was not effective in delaying cell membrane permeability when compared with z-VAD-fmk (Fig. 6D), and the difference toward ZOL-treated cells failed to reach any statistical significance (p > 0.05).

Different other partners may constitute a possible link between LMP and MMP. The BH3 protein, Bid, can be cleaved by inducers other than caspase-8, like cathepsin L (50, 51), cathepsins B and D, granzyme B, and c-Jun N-terminal kinase. tBid acts further on mitochondria to cause MMP and caspase activation (30). However, no decrease in full-length Bid could be seen (Fig. 6F) using an antibody that recognizes the uncleaved 22-kDa protein, indicating that Bid clearly does not contribute to MMP in ZOL-induced cell death and consequently is not the link between LMP and MMP in our system.

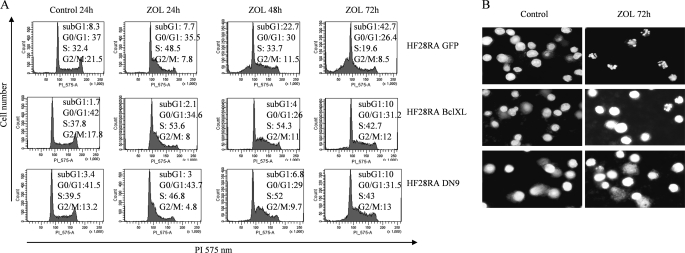

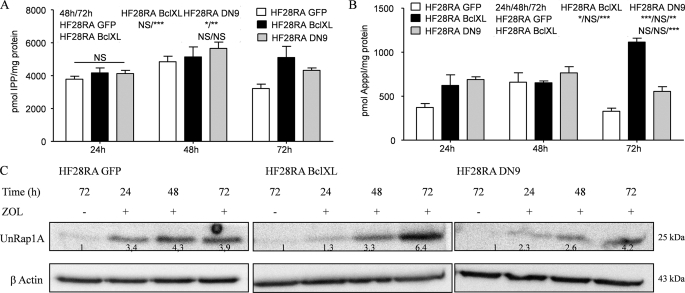

Mevalonate Pathway and Protein Prenylation Are Blocked by ZOL in Modified HF28RA Cells

Exposure to 50 μm ZOL leads to accumulation of IPP (Fig. 7A) and ApppI (Fig. 7B) at all time points studied in every HF28RA cell type. There were no considerable differences between the cell lines at 24 and 48 h. However, at 72 h, the IPP and ApppI levels were significantly higher in BclXL-overexpressing cells. ZOL also caused the accumulation of unprenylated Rap1A in the cytoplasmic fraction in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 7C). Again, at 72 h the levels of unprenylated Rap1A were higher in BclXL-overexpressing cells compared with the other two cell lines.

FIGURE 7.

Accumulation of IPP, ApppI, and UnRap1A in HF28RA BclXL and DN caspase-9 cells. The molar amounts of IPP (A) and ApppI (B) were determined in extracts of ZOL-treated cells by using HPLC-ESI-MS. The data are presented as the mean ± S.E. from at least three independent experiments. The statistical significance of the differences was determined using the ANOVA test with the Bonferroni post-test; NS, not significant (p > 0.05); p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***) versus the treated cells (see the data included in the graph). C, shown is the effect of ZOL on Rap1A prenylation as determined by Western blot analysis of UnRap1A in HF28RA control GFP-, BclXL-, and DN caspase-9-transfected constructs. Numbers underneath the bands represent densitometric analysis using ImageJ software, normalized to the internal control (β-actin) and relative to the respective UnRap1A level from an untreated sample, which was set to 1.

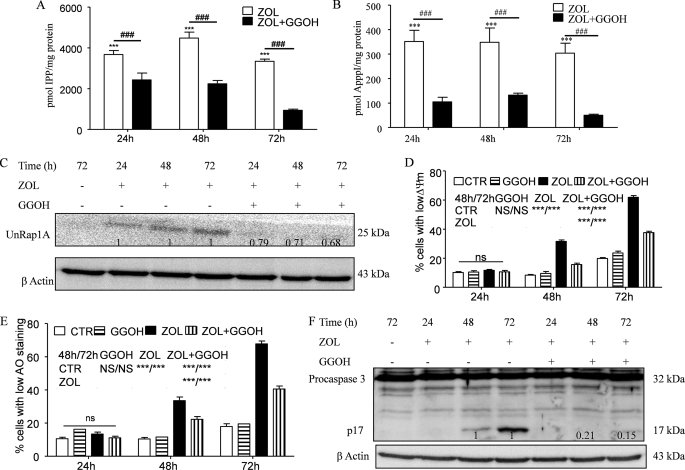

GGOH is an isoprenoid lipid substrate that is converted to geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (52), an intermediate of the mevalonate pathway, downstream of FPP synthase. Geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate serves as a substrate for geranylgeranylation of proteins. It has been shown in several studies (15, 53) that GGOH can rescue certain cell types from ZOL-induced apoptosis. Previously we showed that the protective ability of GGOH could be explained at least in part by its capacity to inhibit IPP/ApppI formation upon ZOL treatment (15). This mechanism acts in concert with the inhibition of accumulation of unprenylated proteins. Thus, we studied the efficacy of GGOH in preventing ZOL-induced cell death also in the HF28RA cell line. Co-treatment with 10 μm GGOH (found to be the highest concentration with no effect on cell viability and apoptosis, data not shown) was associated with a significant decrease of ZOL-induced IPP (Fig. 8A) and ApppI (Fig. 8B) as well as with ZOL-induced accumulation of unprenylated Rap1A (Fig. 8C).

FIGURE 8.

Effect of GGOH on accumulation of IPP/ApppI and unprenylated proteins upon ZOL exposure and their role in ZOL-induced apoptosis. The effect of coincubation with 10 μm GGOH and 50 μm ZOL for different times up to 72 h in the control HF28RA cell line on the accumulation of IPP (A) and the production of ApppI (B) as determined in cell extracts by HPLC-ESI-MS and 1 μm AppCp as the internal standard is shown. Data are the mean ± S.E., n = 4–8; ***, p < 0.001 versus control; ###, p < 0.001 for ZOL alone versus combination with 10 μm GGOH. C, shown is a Western blot analysis of UnRap1A kinetic in HF28RA GFP cells treated with ZOL alone or in combination with 10 μm GGOH. Numbers underneath the bands represent densitometric analysis using ImageJ software, normalized by the internal control (β-actin) and relative to the UnRap1A levels from a corresponding ZOL-treated sample which was set to 1. Mitochondrial membrane potential (D) and lysosomal membrane permeabilization (E) were assessed by TMRM and AO, respectively, followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. 5000 events per condition were collected for each histogram. Graphs represent the mean values of three independent experiments. Error bars represent the S.E. deviation. Statistical evaluation of the data was performed using the ANOVA test; NS, not significant (p > 0.05); p < 0.05 (*), p < 0.01 (**), and p < 0.001 (***) versus the indicated treated cells (see the symbols included in the graph). CTL, control. F, shown is a Western blot analysis of caspase-3 cleavage kinetic in HF28RA GFP cells treated with ZOL alone or in combination with 10 μm GGOH. Numbers underneath the bands represent a densitometric analysis using ImageJ software, normalized by the internal control (β-actin) and relative to the p17 fragment level from corresponding ZOL-treated sample which was set to 1.

In terms of apoptosis, co-incubation of 50 μm ZOL with 10 μm GGOH significantly prevented MMP (p < 0.001, when compared with ZOL treatment alone versus combination with GGOH, Fig. 8D), LMP (Fig. 8E), and cell membrane disruption (data not shown). Again, the inhibitory profile of MMP and LMP is similar, suggesting interactive signaling between lysosomes and mitochondria. However, the inhibitory effect was not complete, which is in agreement with our previous data that indicated that the remaining IPP/ApppI level after co-treatment (Fig. 8, A and B) could still have an effect on mitochondria and induce apoptosis. Additionally, GGOH was effective in preventing cytochrome c release from mitochondria (Fig. 6C) and, as a consequence, completely abolished caspase-3 activation (Fig. 8F), consistent with the idea that inhibition of the mevalonate pathway represents the basic mechanism in ZOL-induced apoptosis in the follicular lymphoma cell line.

DISCUSSION

In this study we show that ZOL-induced apoptosis in the HF28RA cell line is associated with MMP, release of cytochrome c into the cytosol, activation of caspase-3, and DNA fragmentation. Mitochondria serve as executors of apoptosis in ZOL-mediated cell death. All these apoptotic features are completely abrogated by BclXL overexpression and the DN caspase-9 construct of the HF28RA cell line. These findings are in line with previous studies showing the central role of mitochondria in caspase-dependent and -independent apoptosis induced by ZOL, but the exact mechanisms were still unknown. BclXL overexpression delays mitochondrial-induced apoptosis induced by different stimuli (28, 31, 54), and reported is the inhibition of ZOL-induced apoptosis by ectopic overexpression of Bcl-2 in different myeloma cell lines, but this is the first study to show that BclXL overexpression and the DN caspase-9 construct can protect cells against ZOL-induced apoptosis.

Despite emerging data on the mechanism of ZOL-induced apoptosis, the involvement of lysosomes in this process has not been previously reported. Here we show that ZOL induces a gradual increase of LMP in the lymphoma cell line. This effect is blocked by BclXL overexpression and the DN caspase-9 construct, indicating that BclXL and caspase-9 are key mediators also involved in this process. On the basis of current data, it seems obvious that mitochondria and lysosomes are having a non-dissociated cross-talk in coordinating cellular dismantling.

Overexpression of BclXL, an antiapoptotic protein that completely preserved mitochondrial functions in our model, also blocked lysosomal disruption as shown by LMP measurements. This outcome suggests that lysosomal damage depends at least in part on mitochondrial damage. These results are in agreement with previous studies where overexpressed Bcl-XL prevented free fatty acid (55) and camptothecin (49)-induced lysosomal permeabilization in various cell lines. On the other hand, the incapability of BclXL, Bcl-2, or vMIA (cytomegalovirus cell death suppressor) overexpression to stabilize lysosomal membrane is associated with the conclusion that lysosomes are the first organelles affected by these drugs. This has been shown for hydroxychloroquine using various cell lines (36).

Surprisingly, inactivation of caspase-9 in HF28RA cells was able to prevent all apoptotic events induced by ZOL, including MMP and LMP. Moreover, the inhibitory profile of these two apoptotic features was identical. A recent study (56) showed that small interfering RNA against caspase-3 and -9 rendered human keratinocytes and gingival fibroblasts resistant to the antiproliferative and apoptotic effects of ZOL, but the underlying mechanisms were not discussed. Our results are in agreement with previous studies (57) obtained with the same HF29RA DN caspase-9 cell line and showing that rituximab-induced release of cytochrome c and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential were regulated by caspase-9. Additionally, it has been reported (39) that overexpression of the DN caspase-9 construct in HF28RA cells delayed apoptosis and decreased the proportion of cells with a depolarized membrane in TRAIL-induced cell death.

So far it is generally accepted that caspase-9 acts downstream to mitochondria. However, caspase-9 could be also activated independently of the release of mitochondrial proteins (58). Our observation that the DN caspase-9 construct inhibits ZOL-induced MMP and LMP suggests that caspase-9 can serve as an amplification loop for MMP, and as a consequence, MMP occurs before or concomitantly with LMP. Additionally, our data indicate that caspase-9 can also act as a direct regulator of LMP. This scenario has been proposed previously (59).

Pharmacological inhibitors of caspases and cathepsins were used to further address their role in ZOL-induced apoptosis. This strategy has been employed earlier to determine the dynamic spatiotemporal coordination between mitochondria and lysosomes in apoptosis (36). We used z-VAD-fmk, an irreversibly cell-permeant pan caspase inhibitor, and a broad spectrum papain-like cysteine protease inhibitor, E-64. Caspase inhibition by z-VAD-fmk did not completely block ZOL-induced cell death, which is in line with the notion that caspase-independent death co-exists in ZOL-treated follicular lymphoma cells (11). Additionally, z-VAD-fmk was endowed with the capacity to inhibit LMP, suggesting that caspases are involved in lysosomal destabilization. In contrast, E64 was not able to prevent caspase-3 activation after ZOL exposure. This outcome suggests that a direct link between cathepsins and caspase-3 activation is improbable. This is in agreement with previous data (50) showing that lysosomal lysates do not activate caspase-2, -3, -6, -8, or caspase-9 in vitro. Apoptotic caspases are poor substrates for most cathepsins (60), but recently it was demonstrated that cathepsins can mediate caspase-dependent apoptosis downstream of mitochondria (61) or activate caspases through an indirect mechanism (43). Altogether, these data not only give a mechanistic understanding for ZOL-induced apoptosis but also show more generally the existence of a coordinated sequence of biochemical events, where lysosomal damage is dependent on mitochondrial destabilization in drug-induced apoptosis. Using different strategies, our data suggest that lysosomal destabilization is the consequence of mitochondrial damage. Moreover, lysosomal damage acts as an amplification loop for MMP.

An interesting and intriguing result presented in this paper is that S-phase arrest induced by ZOL in HF28RA wild type cells at early incubation times (24 h) was preserved by BclXL and DN caspase-9-overexpressing constructs at long exposures, thus blocking the progression toward sub-G1 region. Previously, Bcl-XL along with Bcl-2 has been implicated in cell cycle regulation (63). It was reported previously (64) that BclXL interacts with cdk1 (cdc2) during the G2/M cell cycle checkpoint, its overexpression stabilizes a G2/M arrest senescence program in surviving cells after DNA damage, and its effect is genetically distinct from its function on apoptosis. Even though we could give a plausible explanation for how BclXL might keep the cells in S-phase by interacting with different cell cycle regulators, cell cycle delay in DN caspase-9 mutant cells is still unexpected. The mechanism of how BclXL-overexpressing and DN caspase-9-engineered cells block cell cycle progression in S phase upon ZOL exposure deserves further investigation.

An additional important issue of this study is the involvement of the mevalonate pathway and subsequent protein prenylation inhibition in ZOL-induced apoptosis in follicular lymphoma cells. Prenylated proteins are critical intermediates of cell signaling and cytoskeletal organization (65). To investigate the role of protein prenylation in ZOL-mediated apoptosis in the HF28RA cell line, we determined if the isoprenoid lipid, GGOH, could rescue the cells from cell death. It is known that GGOH has the ability to prevent or attenuate the proapoptotic effects of nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates (53, 62, etc). In this study GGOH was able to significantly decrease but not totally abolish IPP and ApppI accumulation in the HF28RA cell line and to decrease, but not completely block, the apoptotic features caused by ZOL. Our data are in perfect agreement with our previous study (15) which shows that the remaining amount of IPP/ApppI could still cause cell death, and there exists a threshold for the IPP and/or ApppI levels required for apoptosis.

ZOL causes a similar IPP/ApppI accumulation and inhibition of Rap1A prenylation in GFP as well as in BclXL and DN caspase-9-overexpressing HF28RA cells, indicating similar inhibition of the mevalonate pathway. Our data do not give an unequivocal answer for the involvement of unprenylated proteins in ZOL-induced apoptosis, and the possibility that this signaling pathway does not interact with mitochondria cannot be ruled out. However, z-VAD-fmk and E64 did not affect UnRap1A accumulation (data not shown), but z-VAD-fmk decreased MMP and LMP caused by ZOL. This strongly suggests that the accumulation of unprenylated proteins is not an absolute prerequisite for ZOL-induced apoptosis. Moreover, GGOH was able to decrease IPP/ApppI accumulation, MMP and LMP, cytochrome c release, and caspase-3 activation, strongly indicating that overall inhibition of the mevalonate pathway is the key event for apoptosis caused by nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates.

In conclusion, this study identifies mechanisms for ZOL-induced apoptosis revealing the interplay between mitochondria and lysosomes as executors of cell dismantling. The question of whether accumulation of unprenylated proteins or IPP/ApppI dictates ZOL-induced apoptosis cannot be completely answered, but clearly the accumulation of unprenylated proteins is not sufficient. These studies could open new perspectives to maximize the effects of ZOL in resistant cancer cells by using it in combination with drugs that inhibit the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase pathway, the lysosomal localization of heat shock protein 70, or the activity of cathepsin inhibitors (e.g. cystatin, serpins) (43) and, thus, be helpful in designing further rational therapeutic protocols.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lea Pirskanen for valuable technical assistance and friendship, Ulla Nuutinen (Dept. of Clinical Microbiology, University of Kuopio, Finland) for providing positive controls for caspase-8 and Bid detection and for helpful discussions, Eila Pelkonen (Dept. of Clinical Microbiology, University of Kuopio, Finland) for assistance with Western blots, and Dr. Jonathan Green for critical reading.

This work was supported by NOVARTIS AG, Basel, Switzerland (to L. M.).

- ZOL

- zolendronic acid

- IPP

- isopentyl pyrophosphate

- ApppI

- triphosphoric acid 1-adenosin-5′-yl ester 3-(3-methylbut-3-enyl) ester

- HF28RA

- human follicular lymphoma cells

- BclXL

- Bcl-2 family receptor

- DN9

- dominant negative caspase-9

- MMP

- mitochondrial membrane permeabilization

- LMP

- lysosome membrane permeabilization

- z-VAD-fmk

- benzyloxycarbonyl-VAD-fluoromethyl ketone, procaspase inhibitor

- E64

- broad spectrum cathepsin inhibitor

- FPP

- farnesyl pyrophosphate

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- GGOH

- geranylgeraniol

- AppCp

- metabolites of non-nitrogen-containing bisphosphonates

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- ΔΨm

- mitochondrial membrane potential

- TMRM

- tetramethylrhodamine methyl ester

- AO

- acridine orange

- HPLC-ESI-MS

- HPLC negative ion electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- TRAIL

- tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Flanagan A. M., Chambers T. J. (1991) Calcif. Tissue Int. 49, 407–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Delmas P. D. (2002) Lancet 359, 2018–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roux C., Dougados M. (1999) Drugs 58, 823–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman R. E. (2004) Breast 13, S19–S28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Massaia M., Mariani S., Pantaleoni F., Muraro M., Peola S., Hwang S. Y., Castella B., Matta G., Foglietta M., Fiore F., Coscia M., Boccadoro M. (2005) Haematol. Rep. 1, 77–80 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gnant M., Mlineritsch B., Schippinger W., Luschin-Ebengreuth G., Pöstlberger S., Menzel C., Jakesz R., Seifert M., Hubalek M., Bjelic-Radisic V., Samonigg H., Tausch C., Eidtmann H., Steger G., Kwasny W., Dubsky P., Fridrik M., Fitzal F., Stierer M., Rücklinger E., Greil R., Marth C. (2009) N. Engl. J. Med. 360, 679–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Green J. R. (2003) Cancer 97, 840–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winter M. C., Holen I., Coleman R. E. (2008) Cancer Treat. Rev. 34, 453–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Beek E., Pieterman E., Cohen L., Löwik C., Papapoulos S. (1999) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 264, 108–111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luckman S. P., Hughes D. E., Coxon F. P., Graham R., Russell G., Rogers M. J. (1998) J. Bone Miner. Res. 13, 581–589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ory B., Blanchard F., Battaglia S., Gouin F., Rédini F., Heymann D. (2007) Mol. Pharmacol. 71, 333–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sewing L., Steinberg F., Schmidt H., Göke R. (2008) Apoptosis 13, 782–789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Russell R. G., Watts N. B., Ebetino F. H., Rogers M. J. (2008) Osteoporos. Int. 19, 733–759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mönkkönen H., Auriola S., Lehenkari P., Kellinsalmi M., Hassinen I. E., Vepsäläinen J., Mönkkönen J. (2006) Br. J. Pharmacol. 147, 437–445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitrofan L. M., Pelkonen J., Mönkkönen J. (2009) Bone 45, 1153–1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasmim M., Bieler G., Rüegg C. (2007) J. Thromb. Haemost. 5, 166–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tassone P., Tagliaferri P., Viscomi C., Palmieri C., Caraglia M., D'Alessandro A., Galea E., Goel A., Abbruzzese A., Boland C. R., Venuta S. (2003) Br. J. Cancer 88, 1971–1978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dunford J. E., Rogers M. J., Ebetino F. H., Phipps R. J., Coxon F. P. (2006) J. Bone Miner Res. 21, 684–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dickson P. V., Hamner J. B., Cauthen L. A., Ng C. Y., McCarville M. B., Davidoff A. M. (2006) Surgery 140, 227–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evdokiou A., Labrinidis A., Bouralexis S., Hay S., Findlay D. M. (2003) Bone 33, 216–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fromigue O., Lagneaux L., Body J. J. (2000) J. Bone Miner Res. 15, 2211–2221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hengartner M. O. (2000) Nature 407, 770–776 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fulda S., Meyer E., Friesen C., Susin S. A., Kroemer G., Debatin K. M. (2001) Oncogene 20, 1063–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Adrain C., Martin S. J. (2001) Trends Biochem. Sci. 26, 390–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferri K. F., Kroemer G. (2001) Nat. Cell Biol. 3, E255–E263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ravagnan L., Roumier T., Kroemer G. (2002) J. Cell Physiol. 192, 131–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green D. R., Reed J. C. (1998) Science 281, 1309–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kroemer G., Reed J. C. (2000) Nat. Med. 6, 513–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gross A., McDonnell J. M., Korsmeyer S. J. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 1899–1911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim R. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 333, 336–343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kroemer G. (1997) Nat. Med. 3, 614–620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boya P., Kroemer G. (2008) Oncogene 27, 6434–6451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhao M., Antunes F., Eaton J. W., Brunk U. T. (2003) Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 3778–3786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katunuma N., Matsui A., Le Q. T., Utsumi K., Salvesen G., Ohashi A. (2001) Adv. Enzyme Regul. 41, 237–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cirman T., Oresić K., Mazovec G. D., Turk V., Reed J. C., Myers R. M., Salvesen G. S., Turk B. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3578–3587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boya P., Andreau K., Poncet D., Zamzami N., Perfettini J. L., Metivier D., Ojcius D. M., Jäättelä M., Kroemer G. (2003) J. Exp. Med. 197, 1323–1334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terman A., Gustafsson B., Brunk U. T. (2006) Mol. Aspects Med. 27, 471–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leist M., Jäättelä M. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 589–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nuutinen U., Simelius N., Ropponen A., Eeva J., Mättö M., Eray M., Pellinen R., Wahlfors J., Pelkonen J. (2009) Leuk. Res. 33, 829–836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castedo M., Ferri K., Roumier T., Métivier D., Zamzami N., Kroemer G. (2002) J. Immunol. Methods 265, 39–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nicoletti I., Migliorati G., Pagliacci M. C., Grignani F., Riccardi C. (1991) J. Immunol. Methods 139, 271–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zdolsek J. M., Olsson G. M., Brunk U. T. (1990) Photochem. Photobiol. 51, 67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fehrenbacher N., Jäättelä M. (2005) Cancer Res. 65, 2993–2995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X., Kim C. N., Yang J., Jemmerson R., Wang X. (1996) Cell 86, 147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bossy-Wetzel E., Newmeyer D. D., Green D. R. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 37–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Talanian R. V., Quinlan C., Trautz S., Hackett M. C., Mankovich J. A., Banach D., Ghayur T., Brady K. D., Wong W. W. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 9677–9682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paris C., Bertoglio J., Bréard J. (2007) Apoptosis 12, 1257–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chuah C., Barnes D. J., Kwok M., Corbin A., Deininger M. W., Druker B. J., Melo J. V. (2005) Leukemia 19, 1896–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Paquet C., Sané A. T., Beauchemin M., Bertrand R. (2005) Leukemia 19, 784–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stoka V., Turk B., Schendel S. L., Kim T. H., Cirman T., Snipas S. J., Ellerby L. M., Bredesen D., Freeze H., Abrahamson M., Bromme D., Krajewski S., Reed J. C., Yin X. M., Turk V., Salvesen G. S. (2001) J Biol. Chem. 276, 3149–3157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zamzami N., El Hamel C., Maisse C., Brenner C., Muñoz-Pinedo C., Belzacq A. S., Costantini P., Vieira H., Loeffler M., Molle G., Kroemer G. (2000) Oncogene 19, 6342–6350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fisher J. E., Rogers M. J., Halasy J. M., Luckman S. P., Hughes D. E., Masarachia P. J., Wesolowski G., Russell R. G., Rodan G. A., Reszka A. A. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 133–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jagdev S. P., Coleman R. E., Shipman C. M., Rostami-H A., Croucher P. I. (2001) Br. J. Cancer 84, 1126–1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Aparicio A., Gardner A., Tu Y., Savage A., Berenson J., Lichtenstein A. (1998) Leukemia 12, 220–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Feldstein A. E., Werneburg N. W., Li Z., Bronk S. F., Gores G. J. (2006) Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 290, G1339–G1346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scheper M. A., Badros A., Chaisuparat R., Cullen K. J., Meiller T. F. (2009) Br. J. Haematol. 144, 667–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eeva J., Nuutinen U., Ropponen A., Mättö M., Eray M., Pellinen R., Wahlfors J., Pelkonen J. (2009) Apoptosis 14, 687–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Morishima N., Nakanishi K., Takenouchi H., Shibata T., Yasuhiko Y. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 34287–34294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gyrd-Hansen M., Farkas T., Fehrenbacher N., Bastholm L., Høyer-Hansen M., Elling F., Wallach D., Flavell R., Kroemer G., Nylandsted J., Jäättelä M. (2006) Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 7880–7891 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Turk B., Stoka V., Rozman-Pungercar J., Cirman T., Droga-Mazovec G., Oresić K., Turk V. (2002) Biol. Chem. 383, 1035–1044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Droga-Mazovec G., Bojic L., Petelin A., Ivanova S., Romih R., Repnik U., Salvesen G. S., Stoka V., Turk V., Turk B. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 19140–19150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Coxon J. P., Oades G. M., Kirby R. S., Colston K. W. (2004) BJU Int. 94, 164–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Janumyan Y. M., Sansam C. G., Chattopadhyay A., Cheng N., Soucie E. L., Penn L. Z., Andrews D., Knudson C. M., Yang E. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 5459–5470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Schmitt E., Beauchemin M., Bertrand R. (2007) Oncogene 26, 5851–5865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schafer W. R., Rine J. (1992) Annu. Rev. Genet. 26, 209–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]