Abstract

Numerous intracellular pathogens exploit cell surface glycoconjugates for host cell recognition and entry. Unlike bacteria and viruses, Toxoplasma gondii and other parasites of the phylum Apicomplexa actively invade host cells, and this process critically depends on adhesins (microneme proteins) released onto the parasite surface from intracellular organelles called micronemes (MIC). The microneme adhesive repeat (MAR) domain of T. gondii MIC1 (TgMIC1) recognizes sialic acid (Sia), a key determinant on the host cell surface for invasion by this pathogen. By complementation and invasion assays, we demonstrate that TgMIC1 is one important player in Sia-dependent invasion and that another novel Sia-binding lectin, designated TgMIC13, is also involved. Using BLAST searches, we identify a family of MAR-containing proteins in enteroparasitic coccidians, a subclass of apicomplexans, including T. gondii, suggesting that all these parasites exploit sialylated glycoconjugates on host cells as determinants for enteric invasion. Furthermore, this protein family might provide a basis for the broad host cell range observed for coccidians that form tissue cysts during chronic infection. Carbohydrate microarray analyses, corroborated by structural considerations, show that TgMIC13, TgMIC1, and its homologue Neospora caninum MIC1 (NcMIC1) share a preference for α2–3- over α2–6-linked sialyl-N-acetyllactosamine sequences. However, the three lectins also display differences in binding preferences. Intense binding of TgMIC13 to α2–9-linked disialyl sequence reported on embryonal cells and relatively strong binding to 4-O-acetylated-Sia found on gut epithelium and binding of NcMIC1 to 6′sulfo-sialyl Lewisx might have implications for tissue tropism.

Keywords: Carbohydrate/Lectin, Cell/Adhesion, Methods/Microarray, Parasitology, Toxoplasma gondii, Host Cell Invasion, Microneme Proteins, Sialic Acid

Introduction

Sialic acids (Sias)6 occur abundantly in glycoproteins and glycolipids on the cell surface and are exploited by many viruses and bacteria for attachment and host cell entry. Recognition of carbohydrates and in particular sialylated glycoconjugates is important also for host cell invasion by the Apicomplexa (1–4), a phylum that includes several thousand species of obligate intracellular parasites, among them the Plasmodium spp. causing malaria. Enteroparasitic coccidians are a subclass of Apicomplexa comprising Eimeria spp. responsible for coccidiosis in poultry, Neospora spp. causing neosporosis in cattle, and Toxoplasma, the causative agent of toxoplasmosis in warm-blooded animals and humans.

The host range and cell type targeted by these parasites vary widely across the phylum. Whereas Plasmodium falciparum merozoites exclusively invade erythrocytes of humans and great apes (5), Toxoplasma gondii tachyzoites (the form of the parasite associated with acute infection) invade an extremely broad range of cell types in humans and virtually all warm-blooded animals, enabling rapid establishment of infection in the host and dissemination into deep tissues (6). Information is emerging on the involvement of carbohydrate-protein interactions in this broad host cell recognition (1).

Many intracellular pathogens have evolved to manipulate the phagocytic pathways of host cells during invasion. This contrasts with invasion by apicomplexans, which express their own machinery for active host cell entry. Invasion is a multistep process requiring the tightly regulated discharge of parasite organelles called micronemes and rhoptries (7). Micronemes release adhesins (MICs) onto the parasite surface, which form multiprotein complexes with nonoverlapping roles in motility, host cell attachment, secretion of rhoptry organelles, and cell penetration (8). After attachment and reorientation of the parasite, invasion induces the formation of a nonfusogenic parasitophorous vacuole derived in large part from host cell plasma membranes (9). The MICs share a limited number of adhesive domains arranged in various combinations and numbers (10). These domains are implicated in host cell recognition and attachment and are believed to contribute to host cell type specificity and hence disease pathology.

T. gondii microneme protein 1 (TgMIC1) forms a complex with TgMIC4 and TgMIC6 (11, 12) and binds to sialylated glycoconjugates on the host cell surface (1). Previous studies based on gene disruption have established a critical role for the complex in host cell invasion in tissue culture and its contribution to virulence in vivo (13). The N-terminal region of TgMIC1 interacts with TgMIC4, a protein comprising six “apple” domains that has been shown to bind to host cells in the presence of TgMIC1 (11). TgMIC6 contains three epidermal growth factor (EGF)-like domains and is a type I membrane protein, which serves as an escorter and anchors the TgMIC1-MIC4-MIC6 (TgMIC1-4-6) complex to the parasite surface during invasion (12). The first EGF-like domain (TgMIC6-EGF1) is cleaved off during secretory transport of the complex, probably in a post-Golgi compartment (14). Each of the remaining two EGF-like domains is able to recruit one molecule of TgMIC1 via interaction with its C-terminal galectin-like domain (for a schematic see Fig. 1A) (12, 15, 16). Correct trafficking of the complex to the micronemes depends not only on a sorting determinant in the C-terminal tail of TgMIC6 but also on the interaction between the galectin-like domain of TgMIC1 (TgMIC1-GLD) with the third membrane-proximal EGF-like domain of TgMIC6 (TgMIC6-EGF3). This interaction is crucial for transport of the entire complex through the early secretory pathway as it assists proper folding of TgMIC6-EGF3, providing a quality control checkpoint (12, 15, 17).

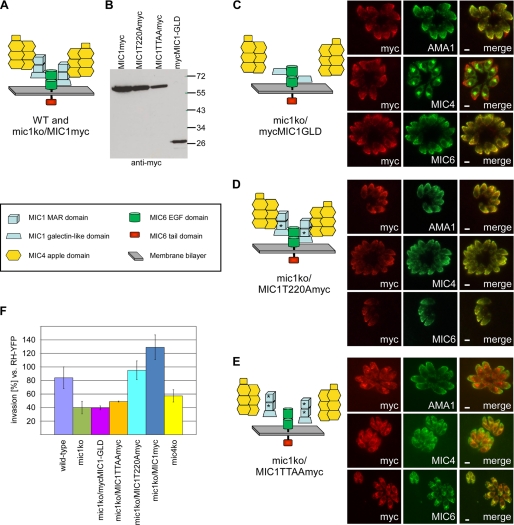

FIGURE 1.

Cooperative function for the Sia-binding TgMIC1-MAR domains and TgMIC4 in host cell invasion by T. gondii. A, schematic summarizing the domain organization of the components of the TgMIC1-4-6 complex in the WT and mic1ko/MIC1myc complemented strains. B, Western blot analysis of parasite lines expressing TgMIC1 mutant proteins on the mic1ko background. C–E, TgMIC1 mutant proteins expressed on the mic1ko background were assessed for their ability to substitute for TgMIC1 and target the components of the TgMIC1-4-6 complex to the micronemes. IFA was performed on intracellular parasites multiplying in their vacuole. TgAMA-1 is used as a micronemal marker independent of the TgMIC1-4-6 complex. Scale bars, 1 μm. A schematic summarizes the association/dissociation of the components of the TgMIC1-4-6 complex in the different strains. An asterisk indicates a Thr to Ala substitution in the Sia-binding site of the MAR domain. F, comparison of host cell invasion efficiency by the various T. gondii mutant strains using an RH-2YFP strain as internal standard for parasite fitness. Error bars, standard deviation.

Several studies have shown that recognition of carbohydrate structures on the host cell surface is critical for efficient invasion by T. gondii (18–20). We have recently demonstrated that the N-terminal region of TgMIC1 contains two copies of a novel MAR domain and that this region termed TgMIC1-MARR binds specifically to sialylated oligosaccharides as shown by cell binding assays and carbohydrate microarray analyses (1). Also, we observed a 90% reduction of invasion efficiency when N-acetylneuraminic acid (NANA) was used as a competitor or when host cells were treated with neuraminidase (1). This suggested that Sia is a major determinant of host cell invasion by T. gondii and that the effect observed in the invasion assays may be attributed, at least in part, to inhibition of the interaction between TgMIC1 and its host cell receptor(s).

Here, we compare the invasion efficiency of several T. gondii knock-out strains and complemented mutants and demonstrate that the TgMIC1-Sia interaction is indeed important for efficient host cell invasion. We also show that the TgMIC1-4-6 complex is not the only molecular player involved in Sia-dependent invasion by T. gondii tachyzoites. By BLAST searches, we identify a family of MAR domain-containing proteins (MCPs) in T. gondii and related apicomplexan parasites Sarcocystis neurona, Neospora caninum, and Eimeria tenella. Among these we characterize TgMIC13, and we compare the binding specificities of recombinant TgMIC13 with TgMIC1 and its homologue from the closely related organism N. caninum, NcMIC1, by carbohydrate microarray and cell binding assays. Our results indicate that the MAR domain is unique to and conserved among coccidians and that it acts as an important determinant in host cell recognition by these parasites through selective binding to sialylated glycoconjugates.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of T. gondii Mutant Parasite Strains

All T. gondii strains were grown in human foreskin fibroblasts (HFF) or Vero cells in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen), 10% fetal calf serum, 2 mm glutamine, 25 μg/ml gentamicin. The RH strain is referred to as “wild type.”

The mic1ko parasite strain, generated previously (12), was stably complemented with linearized plasmids pM2MIC1myc, pM2MIC1T220Amyc, pM2MIC1T126A,T220Amyc, and pROP1mycMIC1-GLD coding for the expression of TgMIC1myc, TgMIC1T220Amyc, TgMIC1TTAAmyc, and mycTgMIC1-GLD (encompassing amino acids 299–456 of TgMIC1), respectively, using a standard electroporation transfection protocol with restriction enzyme-mediated insertion. For selection, plasmids were cotransfected with p2854_DHFR or pTUB5-CAT (carrying the pyrimethamine and the chloramphenicol resistance marker, respectively) at a 5:1 ratio. pM2MIC1T220Amyc was generated from pM2MIC1myc using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) and primers TgMIC1-20_1731 and TgMIC1-21_1732. pM2MIC1T126A,T220Amyc was obtained by replacing the fragment between restriction sites NdeI and EcoNI in pM2MIC1myc with the equivalent region in plasmid pPICZα-TgMIC1NTT126A,T220A (see Ref. 1). To obtain a clonal line, parasites were cloned at least twice by limiting dilution from the drug-resistant pool of parasites obtained from transfection and selection.

Cloning of T. gondii MCPs

Restriction enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. All primers are listed in supplemental Table 2. Accession numbers are listed in Table 1. TgMIC13, TgMCP3, and TgMCP4 were amplified by PCR from a T. gondii tachyzoite cDNA pool. TgMIC13 with or without the signal peptide was amplified using primer pairs MIC1/2–5/1047 and MIC1/2–6/1048 or MIC1/2–1/1147 and MIC1/2–2/1148, respectively. TgMCP3 was cloned using primers MIC1/3-7_1981 and MIC1/3-7_1982. To obtain the coding sequence for TgMCP4 with or without the signal peptide, primer pairs TgMIC1/4-7_1983 and TgMIC1/4-7_1984 as well as TgMIC1/4-3_1847 and TgMIC1/4-4_1848 were used for amplification, respectively. The fragments were cloned into pGEM and sequenced. The sequence encoding full-length TgMIC13 was digested with EcoRI and SbfI and subcloned into pTUB8TgMLCTy_HX between EcoRI and NsiI restriction sites.

TABLE 1.

Proposed orthologous relationships and GenBankTM (and toxoDB/geneDB/EuPathDB) accession numbers for various MCPs

NI means not identified.

| T. gondii | N. caninum | S. neurona | E. tenella |

| MIC1 | MIC1 | NI | NI |

| CAA96466 | AAL37729 | ||

| (80.m00012) | (NCLIV_043270) | ||

| MIC13/MCP2 | MCP2 | NI | NI |

| ABY81128 | (NCLIV_026810) | ||

| (55.m04865) | |||

| MCP3 | MCP3 | NI | NI |

| CAJ20583 | (NCLIV_003260) | ||

| (25.m00212) | |||

| MCP4 | MCP4 | NI | NI |

| GQ290474 | (NCLIV_003250) | ||

| (25.m01822) | |||

| Not present | MCP5 | MCP5 | NI |

| (NCLIV_066750) | EST4a79g11.y1 | ||

| EST4a34d02.y1 | |||

| Not present | MCP6 | NI | NI |

| (NCLIV_054450) | |||

| Not present | MCP7 | NI | NI |

| (NCLIV_054425) | |||

| Not present | Not present | NI | MIC3 |

| ACJ11219 | |||

| Not present | Not present | NI | MCP2 |

| Contig 29262 |

pTUB8TgMLCTy_HX was cut with EcoRI, blunt-ended with endonuclease, and cut again with NsiI prior to insertion of full-length TgMCP3 coding sequence cut from pGEM-TgMCP3 with EcoRV and PstI. TgMCP3 without signal peptide (SP) was cloned into pROP1mycMIC1-GLD in between NsiI and PacI (blunt end cloning) resulting in pROP1mycTgMCP3(3430).

Full-length TgMCP4 was cloned into pTUB8TgMLCTy_HX using EcoRI and NsiI restriction sites. The sequence corresponding to TgMCP4 without SP was subcloned into pROP1mycMIC1-GLD using NsiI and PacI restriction sites.

Constructs were used in transient transfection experiments in either RHΔHx, mic1ko, or mic6ko parasites. Stable parasite lines were derived from transfection of the pTUB8TgMLCTy_ HX-based vectors carrying the mycophenolic acid/xanthine resistance marker into the RHΔHx strain.

Expression and Purification of MCPs in P. pastoris

Pichia pastoris transformation and expression were performed using pPICZα-based plasmids according to the Pichia expression kit protocols (Invitrogen). Transformation of the supplied host strain GS115 was performed by electroporation following linearization of the vector with PmeI, SacI, or DraI. To inhibit glycosylation, expression was occasionally carried out in the presence of 10 μg/ml tunicamycin. Recombinant TgMIC13 (amino acids 23–468) was either used directly in the form of culture supernatant or purified on nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Qiagen) and concentrated into 20 mm NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, pH 7.3. TgMCP3 (amino acids 54–565) and TgMCP4 (amino acids 526–1016) were not secreted, but soluble α-factor fusion protein was obtained by lysis of cells in 50 mm NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, pH 7.4, 5% glycerol, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride.

Preparation of Excreted Secreted Antigen (ESA) Fraction

T. gondii tachyzoites freshly lysed from their host cells were harvested by centrifugation at 240 × g for 10 min and washed twice in IM (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, 3% fetal bovine serum, 10 mm HEPES) prewarmed to 37 °C. A pellet of 2.0–4.88 × 108 parasites was resuspended in 1 ml of IM, and an aliquot of 50 μl was taken as reference standard to allow estimation of the degree of secretion, and microneme secretion was stimulated by adding 10 μl of 100% EtOH to the remaining 950 μl. The sample was incubated for 10 min at room temperature, then 40 min at 37 °C, and finally cooled down to 0 °C in an ice-water bath for 5 min. Parasites were pelleted at 1000 × g, 4 °C for 5 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged again for 5 min, 4 °C at 2000 × g. The supernatant (ESA) was collected and stored at −80 °C.

Cell Binding Assays

These were performed as described previously (1). Briefly, confluent monolayers of HFF cells were blocked for 1 h at 4 °C with 1% bovine serum albumin in cold PBS, 1 mm CaCl2, 0.5 mm MgCl2 (CM-PBS). Excess bovine serum albumin was removed by two 5-min washes with ice-cold CM-PBS. The proteins to be assayed were then added in the form of P. pastoris culture supernatant (∼0.25 μg in 250 μl) or parasite ESA, together or not with different concentrations of competitors (N-acetylneuraminic acid and glucuronic acid were purchased from Sigma; stock solutions in PBS were adjusted to pH 7.0), and diluted in cold CM-PBS to a total volume of 500 μl. After incubation at 4 °C for 1 h, the supernatant was removed, and the cells were washed four times for 5 min with ice-cold CM-PBS. The cell-bound fraction was collected by the direct addition of 50 μl of 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer with 0.1 m dithiothreitol. In some cases, prior to blocking, HFF cells were pretreated with 66 milliunits/ml α2–3, -6, -8 Vibrio cholerae neuraminidase (Roche Applied Science) in RPMI 1640 medium, 25 mm HEPES, l-glutamine (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 37 °C in a total reaction volume of 1 ml.

CHO-lec2 cells were purchased from the ATCC. All CHO cells were cultured according to ATCC indications. C6 rat glioma cells were propagated in RPMI 1640 medium (Invitrogen), 5% fetal calf serum, 2 mm l-glutamine, 25 μg/ml gentamicin.

Invasion Assays

Comparison of different T. gondii strains for invasion efficiency was done using an RH-2YFP strain (21) as internal standard for parasite fitness. The details were described previously (16). Total number of parasite vacuoles and RH-2YFP parasite vacuoles were counted on 20 microscopic fields on each IFA slide with a minimum of 440 vacuoles in total per slide. Only vacuoles containing at least two parasites were counted to be sure not to count extracellular parasites that resisted washing. Each experiment was repeated at least three times. Statistical analysis was performed using PRISM.

Microarray Analyses of Recombinant MIC Proteins

The sialyloligosaccharide microarrays were generated with 88 lipid-linked oligosaccharide probes (supplemental Table 1), which were arrayed in duplicate on nitrocellulose-coated glass slides at 2 and 5 fmol per spot using a noncontact instrument (22). Analysis of carbohydrate binding of the recombinant His-tagged MIC proteins was performed essentially as described (1). In brief, each His-tagged MIC protein was precomplexed with mouse monoclonal anti-polyhistidine and biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG antibodies (Sigma) in a ratio of 1:2.5:2.5 (by weight) and overlaid onto the arrays at 40 μg/ml for TgMIC1-MARR and TgMIC13 and 20 μg/ml for NcMIC1-MARR. Binding was detected using Alexa 647 fluor-conjugated streptavidin (Molecular Probes). Microarray data analysis and presentation were carried out using dedicated software.7 The binding to oligosaccharide probes was dose-related, and results of 5 fmol per spot are shown.

RESULTS

TgMIC1 Is an Important Player in Sia-dependent Host Cell Invasion by T. gondii

A previously generated TgMIC1 knock-out strain (mic1ko) showed a 50% reduction in invasion efficiency compared with the wild-type strain (13). As the TgMIC1-4-6 complex is disrupted in this strain, and the transport of TgMIC4 and TgMIC6 to the micronemes is ablated resulting in their retention in the early secretory pathway (12), the contribution of the individual components to host cell invasion has remained unresolved (for a schematic of the complex see Fig. 1A). To address this question, we complemented the mic1ko strain with three different TgMIC1 mutant constructs and then examined whether expression of these proteins is able to improve or restore invasion efficiency. A first parasite mutant line named mic1ko/mycMIC1-GLD expresses the TgMIC1 galectin-like domain (TgMIC1-GLD) on the mic1ko background. A second parasite line called mic1ko/MIC1TTAAmyc expresses full-length TgMIC1 carrying Thr to Ala substitutions at two positions (126 and 220) in the binding site of each of the two MAR domains, previously shown to be critical for the host cell binding activity of the TgMIC1-MAR region (TgMIC1-MARR) (1). A third complemented line called mic1ko/MIC1T220Amyc expresses TgMIC1 containing just a single T220A substitution that also abolishes the host cell binding activity of the protein (1). As a control, the mic1ko strain was complemented with full-length wild-type TgMIC1 carrying a Myc tag epitope at the C terminus (parasite line mic1ko/MIC1myc). Expression of the respective mutant proteins was confirmed by Western blot (Fig. 1B). In addition, the previously generated mic4ko line (12) was included in the analyses. Fig. 1F shows a comparison of invasion efficiency of the parental wild-type and the mic1ko lines and confirms the 50% reduction in invasion phenotype previously reported for the mic1ko (13).

Given that TgMIC4 and TgMIC6 are retained in the early secretory pathway in the mic1ko strain, assessment of the subcellular localization of the TgMIC1 mutant proteins, as well as of TgMIC4 and TgMIC6, in the complemented mic1ko parasite lines was important for interpretation of the invasion assay results. Expression of TgMIC1myc in the mic1ko strain rescued the targeting of TgMIC4 and TgMIC6 to the micronemes supplemental Fig. S1 (12). Invasion efficiency in this strain was restored to a level rather higher than the parental wild-type line (Fig. 1F), showing that a complex composed of endogenous TgMIC4 and TgMIC6 together with the epitope-tagged TgMIC1myc is functional in invasion. In agreement with previous studies (15), expression of TgMIC1-GLD in the mic1ko strain brought TgMIC6 to the micronemes but TgMIC4 remained in the endoplasmic reticulum (Fig. 1C). In the invasion assay (Fig. 1F), when compared with mic1ko, mic1ko/ mycMIC1-GLD showed no rescue of phenotype, demonstrating that the TgMIC6-TgMIC1-GLD mutant complex does not contribute to invasion, likely due to the absence of adhesive domains.

In the mic1ko/MIC1T220Amyc line, TgMIC1T220A was targeted to the micronemes, restoring proper trafficking of TgMIC4 and TgMIC6 (Fig. 1D). This mutant invaded significantly better than mic1ko/mycMIC1-GLD (Fig. 1F) despite the fact that the mutation in TgMIC1T220A abrogates the adhesive properties of the protein (1). This suggested that the invasion enhancement observed upon expression of this protein might be solely a result of its capacity to recruit TgMIC4 to the membrane-bound complex and/or residual weak binding of the first TgMIC1 MAR domain not carrying a Thr to Ala substitution. Invasion efficiency of this line was similar to the wild type but lower than the control line mic1ko/MIC1myc, underlining the importance of the adhesive properties of TgMIC1. In the mic1ko/MIC1TTAAmyc line, TgMIC1TTAA was found mainly in the early secretory pathway (Fig. 1E) probably due to incorrect folding of this mutant protein, precluding corroboration of the above results with the single T220A mutant. Therefore, it was not surprising that there was no improvement of invasion efficiency in this line compared with the mic1ko (Fig. 1F).

In the mic4ko strain, the partial TgMIC1-6 complex was delivered to the micronemes (12). This strain invaded more efficiently than mic1ko and mic1ko/mycMIC1-GLD (t tests, p < 0.05, respectively), confirming the critical role of TgMIC1-MARR in invasion (Fig. 1F). In addition the mic4ko strain did not invade as well as the wild type (t test, p < 0.05), suggesting a role for TgMIC4 in invasion in agreement with our observations with the mic1ko/MIC1T220Amyc line or, alternatively, that the presence of TgMIC4 impacts on the proper function of the MAR domains.

Collectively, the characterization of these mutants suggests a cooperative function for TgMIC1-MARR and TgMIC4 in receptor binding and confirms the absence of any adhesive function for TgMIC6 and TgMIC1-GLD. The invasion experiments establish that TgMIC1 function and its contribution to efficient invasion resides in TgMIC1-MARR binding to sialylated glycoconjugates. Furthermore, our data support the idea that TgMIC4 is an adhesin with an important function in host cell invasion.

T. gondii Possesses More Than One Sia-binding Factor Involved in Host Cell Invasion

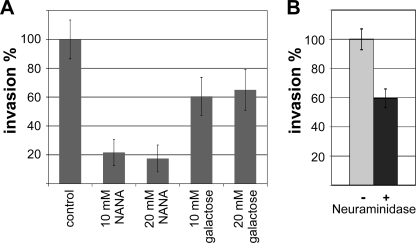

To address the question of whether other parasite lectins bind to host sialylated glycoconjugates during invasion, we tested the effect of free NANA on invasion by the mic1ko strain. Interestingly, this assay showed that host cell invasion by the mic1ko strain was considerably impaired in the presence of free NANA (Fig. 2A), indicating that TgMIC1 is not the only Sia-binding parasite lectin contributing to invasion by T. gondii tachyzoites. This result was corroborated by performing an invasion assay with neuraminidase-treated host cells that resulted in a substantial reduction of invasion by the mic1ko strain (Fig. 2B).

FIGURE 2.

Cell invasion assays using the T. gondii mic1ko strain demonstrate the existence of at least one more Sia-specific parasite lectin. A, invasion by mic1ko parasites in the absence and presence of 10 and 20 mm free NANA or galactose. B, assay comparing invasion of mic1ko parasites into host cells (HFFs) pretreated or not with neuraminidase. Error bars, standard deviation. Note that, compared with the parental strain, the mic1ko shows a 50% reduced invasion phenotype (Fig. 1F), but its invasion efficiency was set to 100% here.

Identification of a Novel Family of MCPs in Coccidia

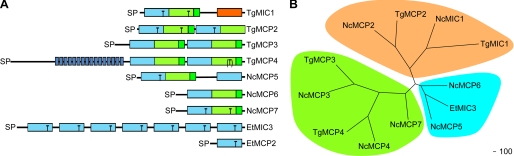

In the light of the above observations, we hypothesized that T. gondii has at least one additional Sia-binding parasite lectin. A survey of the T. gondii genome sequence revealed that it encodes a family of four MCPs, herein named TgMIC1, TgMCP2, TgMCP3, and TgMCP4 (see Table 1, Fig. 3A, and supplemental Fig. S2). The presence in all cases of a predicted N-terminal SP suggests that these proteins are delivered to the secretory pathway. In contrast to TgMIC1, which includes two MAR domains (TgMIC1-MARR) followed by a galectin-like domain (TgMIC1-GLD), the other three sequences contain four consecutive MAR domains but lack a galectin-like domain. In addition, TgMCP4 possesses a novel N-terminal repeat region (16 repeats, 17–22 amino acids per repeat), with the number of repeats varying between different strains of T. gondii. Examination of the EST data set indicate that all these MCP genes are transcribed both in tachyzoite and bradyzoite stages, and a proteomic study (23) showed the expression of TgMCP2 in tachyzoites.

FIGURE 3.

Family of MAR domain-containing proteins in apicomplexans. A, schematic of the domain organization of various MCPs. MAR domain type I (light blue), MAR domain type II (light green), MAR domain type II extension the “β-finger” (green), galectin-like domain (orange), and region of short repeats (blue stripes) are shown. The presence of a Thr in a MAR domain in an equivalent position to those critical for Sia binding in TgMIC1-MARR is indicated by a black T. The fourth MAR domain in TgMCP4 contains this Thr, but the sequence context does not fit with it being indicative of a potential Sia-binding site; therefore, the T is in parentheses. B, phylogenetic relationship of MCPs from T. gondii, N. caninum, and E. tenella. Because the domain structure of the different proteins varies, only the sequence corresponding to the first two predicted MAR domains of each protein was used for the analysis. All bootstrap values are >80. Sequences were aligned in ClustalX, and alignment positions containing gaps in >50% of the sequences were excluded from phylogenetic analyses. Phylogenetic analyses were carried out using POWER (neighbor-joining distance method, bootstrapping with 1000 replicates). Phylogenetic trees were generated using TREEVIEW.

Our earlier studies have established that TgMIC1-MARR has the potential to bind to two molecules of Sia through its two binding sites, one in each MAR domain, characterized by the presence of conserved His and Thr residues. In both binding sites, the Thr residue (Thr-126 and Thr-220, respectively) makes principal contacts to the Sia moiety (1). Sequence comparison reveals that these important Thr residues are not present in either TgMCP3 or TgMCP4 but are conserved in three of the four MAR domains in TgMCP2 (supplemental Fig. S2). Consequently, we hypothesized that TgMCP2 may be another Sia-binding parasite lectin.

Genome-wide BLAST searches of related apicomplexan parasites allowed identification of a complete set of four homologues in N. caninum (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S2). NcMIC1, the homologue of TgMIC1, has been described previously (24), whereas TgMCP2 is highly similar to genemodel NCLIV_026810 (73% identical and 86% similar), and genes coding for proteins highly similar to TgMCP3 (67% identical and 75% similar) and TgMCP4 (73% identical and 80% similar in the MAR region) are present on N. caninum chromosome 1b (supplemental Figs. S3 and S4 show full amino acid sequence alignments). Like TgMCP4, NcMCP4 displays an N-terminal region with short repeats but including only 8 units. Interestingly, the His and Thr signature residues of the MAR Sia-binding site are conserved when comparing the N. caninum and T. gondii homologues, suggesting that these could be functionally equivalent and hence orthologues (supplemental Fig. 2). This view is supported by a phylogenetic analysis comparing the first two predicted MAR domains of each member of the family (Fig. 3B). In this analysis the putative orthologues are indeed most closely related. TgMCP3, TgMCP4, NcMCP3, and NcMCP4 lacking the critical Thr residues form a separate cluster, consistent with an expected functional divergence.

Unfortunately, there were insufficient genomic data available to establish whether a similar gene family exists in another genus of coccidians, Sarcocystis spp., but EST data (SnEST4a79g11.y1, SnEST4a34d02.y1, SnESTbab01e09.y1, SnEST4a69h07.y1, and SnESTbab30h02.y1) indicate the presence of several MAR-containing proteins, one of which (termed SnMCP5) has a homologue in N. caninum (NCLIV_066750 on chromosome12, named NcMCP5 hereafter, see Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S2 and Fig. S4). Despite a high level of synteny between the two parasites, the gene encoding NcMCP5 is absent at the corresponding locus in T. gondii. Two additional loci coding for putative MCPs were found in the N. caninum genome (NCLIV_054450 and NCLIV_054425, named NcMCP6 and NcMCP7, respectively), both composed of an SP and two MAR domains (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S2 and Fig. S5). In E. tenella, the previously described EtMIC3 contains seven MAR domains, in which repeats 3–5 are identical (25). EtMCP2, lying downstream of EtMIC3 on contig 29262, was annotated in silico by comparison with EST data from sporulated oocyst and sporozoite stages. EtMCP2 is composed of an SP and a single MAR domain (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S2 and Fig. S5). In addition, this parasite possesses a number of hypothetical MCPs (two gene models, respectively, on contigs 29652 and 14843). EST data support expression of at least one of them in first generation merozoites. Our BLAST searches failed to identify any MCPs in Plasmodium, Theileria, or Cryptosporidium. Accession numbers and proposed orthologous relationships for all MCPs are depicted in Table 1.

A comparison of MAR domains from Toxoplasma, Neospora, and Sarcocystis highlights differences in disulfide bond patterns between two tandemly arranged MAR domains in a given MCP (supplemental Fig. S2). As in the TgMIC1-MARR prototype, the beginning of the second domain (referred to as type II) lacks a stretch of amino acids containing two cysteine residues shown to participate in the formation of a disulfide bond in the TgMIC1-MARR crystal structure, but it possesses an additional C-terminal extension (with the notable exception of the second MAR domain in TgMCP2 and NcMCP2) that adopts a β-hairpin (1). Curiously, in this regard all the MAR domains in EtMIC3 and in all other predicted MCPs in Eimeria resemble the first of the two tandemly arranged MAR domains, referred to as type I (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S2). This suggests that these proteins have evolved differently in Eimeria compared with the MCPs found in Toxoplasma, Neospora, and Sarcocystis. Therefore, despite the fact that some of the MCPs in Eimeria display the binding site His-Thr or a similar motif, these proteins might possess different properties and functions.

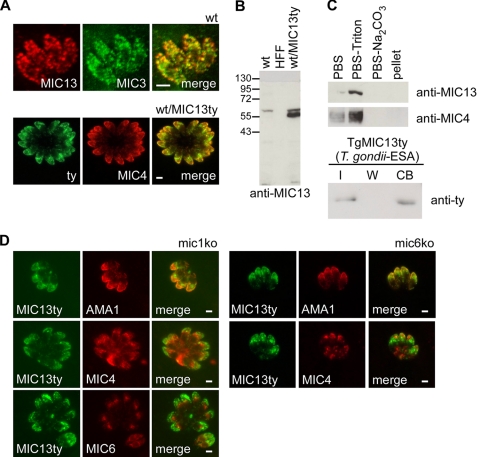

TgMIC13, a Novel Sia-binding Lectin

A parasite line expressing a C-terminal ty-epitope-tagged copy of TgMCP2 was generated. TgMCP2ty was co-localized with TgMIC4 to the micronemes by IFA and was renamed TgMIC13 according to the current nomenclature status. IFA on wild-type parasites using antibodies raised against recombinant TgMIC13 expressed in P. pastoris confirmed localization to the micronemes, although only partial co-localization with TgMIC3 was observed (Fig. 4A). Analysis of lysates from wild type and WT/TgMIC13ty parasites by Western blot indicated that TgMIC13 migrates on SDS-PAGE as a single protein species with an apparent molecular mass (56 kDa) somewhat higher than expected (49.1 kDa calculated from the amino acid sequence) (Fig. 4B). TgMIC13ty migrates slightly faster than endogenous TgMIC13. A similar discrepancy between apparent molecular mass on SDS-PAGE and the expected mass was observed for recombinant TgMIC13 expressed in P. pastoris (Fig. 5A, 59 kDa on SDS-PAGE versus 51.9 kDa expected). No glycosylation sites are predicted for TgMIC13, and mass spectrometric analysis of recombinant TgMIC13 confirmed that its true mass is close to that predicted (supplemental Fig. S7). Therefore, we conclude that the aberrant migration behavior is related to intrinsic properties of the protein. The solubility profile of TgMIC13 is identical to TgMIC4 and is consistent with it being a soluble protein within the parasite organelles (Fig. 4C, upper panel). To assess whether TgMIC13 displays cell binding activity, ESA prepared from WT/TgMIC13ty parasites was tested in a cell binding assay; the protein was found to bind to the cell surface (Fig. 4C, lower panel). Furthermore, transient expression of TgMIC13ty in mic1ko and mic6ko recipient strains indicated that TgMIC13 traffics to the micronemes independently of the TgMIC1-4-6 complex and does not associate with its components (Fig. 4D). These results establish that expression of TgMIC13 cannot functionally rescue the mic1ko, strongly suggesting that TgMIC13 belongs to a distinct complex.

FIGURE 4.

Characterization of TgMIC13 (TgMCP2) in T. gondii. A, IFA shows co-localization of TgMIC13 with microneme proteins in wild-type (wt) (top, confocal images) and in WT/TgMIC13ty parasites (bottom). B, Western blot analysis of endogenous and epitope-tagged TgMIC13 in wild-type and WT/TgMIC13ty parasites. An extract of HFF cells was also loaded as a control. C, assessment of TgMIC13 solubility by fractionation (top). Cell binding assays using ESA from WT/TgMIC13ty parasites (bottom). I, input; W, last of four washes; CB, cell-bound fraction. D, transient transfection of TgMIC13ty into the mic1ko and the mic6ko show correct localization of TgMIC13ty to the micronemes. Scale bars, 1 μm.

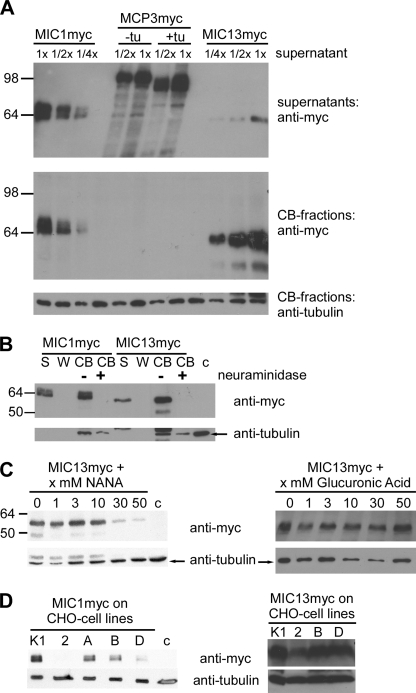

FIGURE 5.

Binding characteristics of recombinant TgMIC13. A, cell binding assays comparing recombinant TgMIC1myc, TgMIC13myc, and α-factor-TgMCP3myc fusion protein produced in P. pastoris; +tu/−tu, protein expressed in the presence/absence of tunicamycin. Top panel, Western blot indicating the relative concentration of the proteins in supernatants used for the assay. Middle panel, cell-bound fractions (CB) probed for bound protein. Bottom panel, control for use of equivalent amounts of cell material in each experiment. B, pretreatment of cells with neuraminidase abolishes binding by TgMIC1 and TgMIC13. S, supernatant; W, last of four washes; CB, cell-bound fraction; c, background control. C, binding of TgMIC13 is strongly reduced in cell binding assays by competition with free NANA but not glucuronic acid. D, binding of TgMIC1 and TgMIC13 to various CHO cell lines (K1, WT strain; 2, lec2 mutant with strong reduction in Sia surface expression; A and B, pgsA745 and pgsB618 mutants deficient in glycosaminoglycan synthesis; D, pgsD677 mutant deficient in two glycosyltransferase activities). Only the cell-bound fractions of the assay are shown.

The cell binding activity of TgMIC13 was reproduced with recombinant protein expressed in P. pastoris (Fig. 5A). Similar to TgMIC1, the binding of TgMIC13 was abolished after pretreatment of cells with neuraminidase (Fig. 5B). Binding of TgMIC13 to host cell receptor(s) could be competed out with free NANA, but it was not affected by increasing concentrations of a control acidic monosaccharide, glucuronic acid (Fig. 5C). However, the binding properties of TgMIC13 differed from TgMIC1 in the following ways: 1) at equivalent concentrations, more TgMIC13 appeared to bind to HFFs) (Fig. 5A); 2) compared with TgMIC1, higher concentrations of NANA were required to fully inhibit receptor binding of TgMIC13 (10 mm for TgMIC1 (1) versus 50 mm for TgMIC13) (Fig. 5C); 3) only extensive treatment of cells with neuraminidase completely abolished the binding of TgMIC13 (data not shown); and 4) TgMIC1 did not bind to CHO lec2 cells that have greatly reduced surface expression of Sia (26), whereas TgMIC13 can weakly bind to them (Fig. 5D). No other differences were observed in cell binding assays with CHO mutants deficient in glycosaminoglycan synthesis (CHO-pgsA and CHO-pgsB) or with CHO cells lacking two glycosyltransferase activities (CHO-pgsD) (Fig. 5D) (27). Taken together, these experiments indicated that TgMIC13 is a Sia-binding lectin with the potential to act during host cell invasion independent of the TgMIC1-4-6 complex. Furthermore, our observations suggested that the cell-binding characteristics of TgMIC13 are different from TgMIC1, possibly binding to different sialylated receptors.

Binding Properties of Other T. gondii Proteins of the MAR Domain Family

Given that the MAR domains on TgMIC1 and TgMIC13 are involved in carbohydrate recognition, we postulated that TgMCP3 and TgMCP4 could also be functional lectins. In cell binding assays using ESA prepared from transgenic parasites expressing TgMCP3ty and TgMCP4ty, neither of the two epitope-tagged proteins showed detectable binding activity (data not shown). Full-length TgMCP3 as well as the MAR region of TgMCP4 (TgMCP4-MARR) encompassing all four MAR domains without the N-terminal repeat region were expressed in both P. pastoris and Escherichia coli. No binding to HFFs could be observed with the recombinant proteins in cell-binding assays (Fig. 5A and data not shown). The lack of binding to Sia-containing moieties would be consistent with the absence of the critical Thr residues in the MAR domains of TgMCP3 and TgMCP4 (supplemental Fig. S2). Homology modeling and sequence alignments suggest that although TgMCP3 and TgMCP4 adopt the MAR fold, they present a largely hydrophobic surface in the equivalent position to the hydrophilic carbohydrate-binding site in TgMIC1 and therefore would not be expected to bind sugars (data not shown).

Carbohydrate Microarray Analyses Reveal Differing Binding Characteristics for TgMIC13, TgMIC1, and NcMIC1

To examine the binding specificities of TgMIC13, we performed cell-independent carbohydrate microarray studies. Preliminary screening analyses with more than 300 lipid-linked oligosaccharide probes (1, 28) showed that recombinant TgMIC13 expressed in P. pastoris bound exclusively to sialylated oligosaccharide probes (supplemental Fig. S6). This is in accord with results of the cell binding assays and shows that Sia is a requirement for TgMIC13 binding.

Details of the binding specificity of TgMIC13 were compared with those of TgMIC1 and NcMIC1 using an array of 88 oligosaccharide probes. These included 82 diverse sialylated oligosaccharide probes with different sialyl linkages and backbone sequences (Fig. 6; supplemental Table S1); 6 neutral oligosaccharide probes served as negative controls. In these experiments we used full-length TgMIC13 expressed in P. pastoris, as well as TgMIC1-MARR (amino acids 17–262) and NcMIC1-MARR (amino acids 17–259), both expressed in E. coli. TgMIC1 lacking its C-terminal galectin-like domain is known to reflect the binding specificities of the full-length protein (1, 16), and we assumed that this is also the case for its homologue NcMIC1. The three proteins bound to various sialylated but not to neutral oligosaccharides in the microarrays. Binding was predominantly observed to α2–3-linked sialyl probes with little or no binding to the α2–6-linked sialyl probes. This is in agreement with a recent study revealing the importance of a glutamic acid residue (Glu-222) in TgMIC1 for this preference (29), which is conserved in TgMIC13 and NcMIC1 (supplemental Fig. S2).

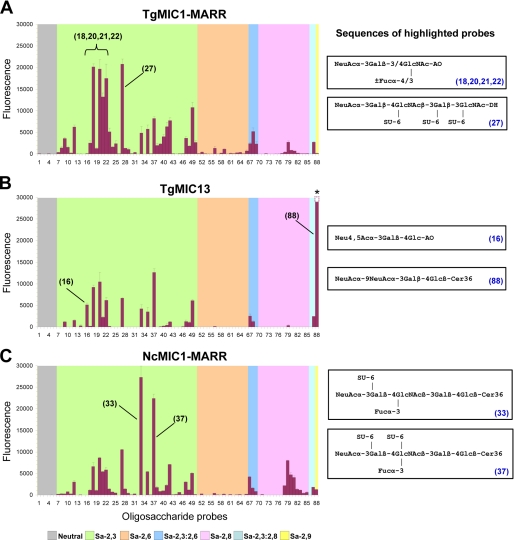

FIGURE 6.

Carbohydrate microarray analyses of recombinant TgMIC1-MARR expressed in E. coli (A), TgMIC13 expressed in P. pastoris (B), and NcMIC1-MARR expressed in E. coli (C) using 88 lipid-linked oligosaccharide probes. Numerical scores of the binding signals are means of duplicate spots at 5 fmol/spot (with error bars). The complete list of probes and their sequences and binding scores are in supplemental Table 1. The binding signal for probe 88 was saturated and could not be accurately quantified (asterisk in B).

Interestingly, for each protein, a distinct binding profile was observed. Among the broad range of sialylated probes bound by TgMIC1-MARR, the preferred ligands are α2–3-linked sialyl-N-acetyllactosamine (3′SiaLacNAc) sequences with or without fucosylation/sulfation on the N-acetylglucosamine residue (highlighted probes in Fig. 6A). This is in overall agreement with previous findings (1). Although the oligosaccharide sequences of probes 18, 20, 21, and 22 are short tri- or tetrasaccharides, their recognition demonstrates the effective presentation of these as oxime-linked neoglycolipids on the array surface (30).

TgMIC13 bound to a more restricted spectrum of probes compared with TgMIC1-MARR (Fig. 6B). Several 3′SiaLacNAc- based probes were bound, but there was little or no binding to sialyl sequences having long chain polyLacNAc or N-glycan backbones (probes 38–41) and to α2–8-polysialyl sequences (probes 76–85). Strikingly, the strongest binding of TgMIC13 was to a disialyllactose probe having α2–9 linkage between the two Sia residues (probe 88) (31). The binding signal for this probe was extremely high (saturated) at the protein concentration tested. In addition, TgMIC13, but not TgMIC1, bound to a little studied 4-O-acetylated 3′sialyllactose sequence as in probe 16. It is interesting that the binding to probe 16 was stronger than that to the non-O-acetylated analogue (probe 12). For NcMIC1-MARR, there was strikingly high binding to two sialyl Lex-related probes (probes 33 and 37, Fig. 6C), which have in common a sulfate group at the 6-position of the galactose residue. In contrast, if the sulfation is on the N-acetylglucosamine residue as in probe 35, binding of NcMIC1-MARR was much weaker. NcMIC1-MARR gave stronger binding signals than TgMIC1 and TgMIC13 with polysialyl sequences.

TgMIC1-MARR Crystal Structure Provides Explanations for the Findings in Microarray Analyses

To better understand the basis of the binding preference revealed by the microarray studies, we compared the crystal structure of TgMIC1-MARR in complex with 3′SiaLacNAc1–3 (Protein Data Bank code 3F5A) (29) to the TgMIC13 MAR domains. Although the first three MAR domains of TgMIC13 possess the Sia-binding signature, we have assumed that the type II domains (MAR2) make the dominant contribution to Sia recognition as observed for TgMIC1-MARR (1); therefore, MAR2 of TgMIC1 and TgMIC13, in particular, was considered. In TgMIC1-MAR2, Lys-216 and Phe-169 from loops β1-β2 and β4-β5 are positioned in proximity to the hydroxyl group on C4 of the Sia ring (Fig. 7A). In the equivalent MAR domain from TgMIC13, the bulky side chains of Lys-216 and Phe-169 are replaced by smaller Ser and Thr residues, respectively, which together with a movement in backbone atoms could enable TgMIC13-MAR2 to accommodate the additional acetyl group at the C4 of Sia.

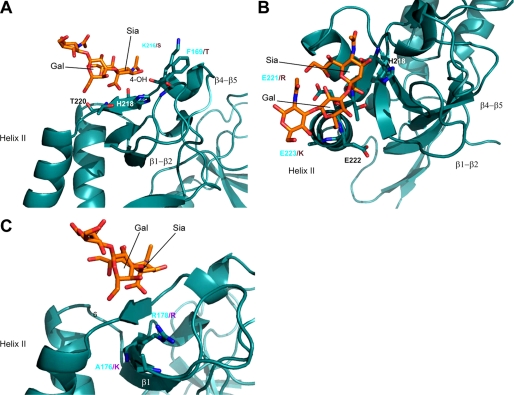

FIGURE 7.

Three orientations of the crystal structure of TgMIC1-MARR in complex with 3′SiaLacNAc1–3 (Protein Data Bank code 3F5A) (29); 3′SiaLacNAc1–3 is shown in an orange stick representation. Key side chains are drawn as stick representations minus attached protons and labeled with sequence position. A and B, amino acid differences between TgMIC1 and TgMIC13 relevant to their binding specificities are labeled in cyan and violet, respectively. C, amino acid differences between TgMIC1 and NcMIC1 relevant to their binding specificities are labeled in cyan and violet, respectively.

In a 2–9-linked disialyloligosaccharide, the two Sia moieties are separated by three additional bonds compared with the separation between Sia and galactose in 3′SiaLacNAc resulting in increased flexibility and making it difficult to predict which amino acids will interact. Assuming a similar mode of recognition for the outermost Sia moiety, one possibility is that the longer linkage would shift the second Sia to a position directly over the end of helix II in TgMIC1-MAR2 (Fig. 7B). In TgMIC1, three consecutive Glu residues (Glu-221–223) cap this helix, which might induce electrostatic repulsion of the negatively charged carboxylate group and hinder any preference for 2–9-disialyl sugars. In TgMIC13, Glu-221 and -223 are replaced by positively charged Arg and Lys residues, which would not only reduce any electrostatic repulsion but provide opportunities for the formation of specific charge-charge interaction with the second Sia.

The preference of NcMIC1-MARR for the two sialyl Lex-related probes sulfated in the 6-position of galactose could be explained by the presence of a positively charged Lys (Lys-176) in NcMIC1-MAR2, which is replaced by an Ala in TgMIC1 (Fig. 7C). By analogy to the complex of TgMIC1-MARR with 3′SiaLacNAc1–3, Lys-176 of NcMIC1 would be spatially closely positioned to the 6-position of galactose and could form a specific charge-charge interaction with the negatively charged sulfate. Lys-176 in NcMIC1 is not conserved in TgMIC13 but is present in NcMCP2.

DISCUSSION

Sia is abundant on glycoconjugates decorating the surface of all vertebrate cells and is widely exploited by viruses and bacteria for host cell entry. In this study, we have characterized key parasite molecular players involved in Sia-dependent host cell invasion by T. gondii. The salient findings are as follows: first, the characterization of TgMIC1-4-6 complex as one important player in Sia-dependent host cell invasion; second, the reliance of the parasite on an additional Sia-binding lectin for invasion, identified as TgMIC13; and third, the determination of distinct Sia-dependent binding specificities for three members of a novel family of MCPs conserved in coccidians. In T. gondii, all the four MCPs are expressed in tachyzoites. Among them, only TgMIC1 and TgMIC13 possess the sequence characteristics of a Sia-binding MAR domain, and only these specifically recognize sialyloligosaccharides.

Role of TgMIC13 in Host Cell Invasion by T. gondii

To contribute to host cell invasion, TgMIC13 needs to be targeted accurately to the micronemes and then delivered in a timely fashion to become firmly anchored on the parasite surface. Because TgMIC13 does not contain a predicted transmembrane domain or glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchor motif, it likely belongs to a yet undefined complex. Expression of TgMIC13 in the mic1ko and mic6ko strains ruled out any interaction with the TgMIC1-4-6 complex. TgMIC13 does not contain a galectin-like domain like TgMIC1, which precludes a similar architecture for the putative TgMIC13-containing complex. Unraveling the mechanism of TgMIC13 sorting to the micronemes must await the identification of its escorter protein, as described for other soluble microneme proteins (12, 14).

To assess precisely the role of TgMIC13 in invasion, we repeatedly tried to knock-out the gene in wild-type (RH strain) and in mic1ko parasites without success using a knock-out cassette with 5-kb flanking elements homologous to the TgMIC13 5′- and 3′-UTRs.8 In addition, knock-out attempts8 failed in a Δ-ku80 strain efficiently amenable to gene disruption by dramatically enhanced frequency of homologous recombination (32, 33). These results suggest that this gene might play an important role for parasite propagation.

Distinct Binding Specificities Might Determine Tissue Tropism of Parasitic Infections

With carbohydrate microarray technology, we examined details of carbohydrate-binding specificities of TgMIC13 in comparison with MAR regions of TgMIC1 and NcMIC1. The preponderant binding activity of all three proteins was to α2–3-linked sialyl probes. However, the relative binding intensities to specific sialyl probes were quite different for the three proteins. TgMIC13 bound to two sialyloligosaccharide probes, namely the 4-O-acetylated sialyllactose and the α2–9-linked disiayl sequences, which were not recognized by TgMIC1 or NcMIC1. The 4-O-acetyl-substituted Sia has been described in various tissues in mice, especially in the gut; its presence has been documented in a number of other animal species and in trace amounts in humans (34, 35). The resistance of 4-O-acetyl-substituted Sia toward neuraminidases from V. cholerae and Clostridium perfringens has previously been described (36, 37), but the susceptibility of this Sia form to neuraminidases requires further detailed investigation. There is so far limited information on the occurrence of 2–9-linked Sia in animals. It has been reported as a component on a murine neuroblastoma cell line (38) and a human embryonal carcinoma cell line (39). The distribution of α2–9-linked disialyllactose in HFFs, C6 rat glioma, and CHO cells has not been described; this and its susceptibility to neuraminidases will be the subject of future investigation.

A special feature of NcMIC1 as revealed by carbohydrate microarray analyses is the strong binding to the two sulfated sialyl Lex-related probes. Sulfation was previously reported to play a role in cell surface binding by NcMIC1 (24); in that study, glycosaminoglycans were proposed to be targeted by NcMIC1; however, the influence of Sia was not investigated. The distinct binding specificities of the three MIC proteins might have implications for tissue tropism, and the cellular targets for these proteins warrant further investigation.

In general, TgMIC1 and TgMIC13 bind with high affinity to 3′SiaLacNAc sequences. Considering the potential spectrum of sialyloligosaccharides that can be bound by these two lectins, and the wide distribution of Sia in vertebrate tissues, it is likely that the two proteins will bind to most cell types. This is in marked contrast to the P. falciparum erythrocyte-binding antigen 175 (PfEBA175), which binds selectively to a unique sialylated glycoprotein, glycophorin A (40, 41). Our results suggest cooperativity between TgMIC1 and TgMIC4 in receptor binding by the TgMIC1-4-6 complex. It will be interesting to investigate if receptor recognition of TgMIC1 is influenced by its association with TgMIC4.

Is There a Molecular Basis for Invasion of a Broad Range of Cells?

The presence of the MAR domain-containing proteins in Toxoplasma, Neospora, Sarcocystis, and Eimeria parasites and its absence in Plasmodium, Theileria, and Cryptosporidium suggest that this domain is exclusively conserved among the Coccidia. We hypothesize that sialylated receptors may be exploited as a common target by a subset of MCPs carrying the appropriate binding motif in this group of enteroparasites. As suggested in our study, not all MCPs would bind to Sia or even to host cells, which raises questions regarding their alternative functions. We have identified a complete set of homologues of T. gondii MCPs in N. caninum, a parasite causing significant economic loss by infecting cattle. T. gondii and N. caninum belong to a group of tissue-cyst-forming coccidians that also include the genera Hammonida, Besnoita, Sarcocystis, and Frenkelia. Similar to T. gondii tachyzoites, N. caninum tachyzoites and S. neurona merozoites are known to be promiscuous pathogens that are able to infect a large variety of cells (42, 43). This is probably related to their common behavior of spreading through tissues during acute infection prior to cyst formation. Considering the fact that the MAR family is restricted to enteroparasites, these adhesins might also be of importance in the context of the natural route of infection via the intestine. To our knowledge, no study has so far addressed the importance of receptor-ligand interactions for invasion of the midgut epithelium.

It is tempting to speculate that the MAR family of lectins is instrumental to the infection of such a broad range of cells. Several lines of evidence support the involvement of TgMIC1 and TgMIC13 and more in general MCPs. First, their binding characteristics are suited for engagement with a variety of cell surface sialyl-glycoconjugates, which are widely distributed in vertebrate tissues. Second, a strain deficient in TgMIC1 and TgMIC3 displays decreased virulence in vivo (13). Importantly, infection of mice with this attenuated strain results in reduced parasite load in a variety of tissues compared with the parental strain (44). Third, as discussed above, the MAR domain appears to be restricted to coccidians. Of note, E. tenella is a coccidian that does not spread through tissues and does not form tissue-cysts but nevertheless also expresses at least one MCP, EtMIC3 (25). Furthermore, EST and genomic data indicate that more MCPs might be expressed. However, our sequence and phylogenetic analyses indicate that Eimeria MCPs are divergent from those present in the cyst-forming coccidians. Therefore, they might serve a different function.

In addition to TgMIC1 and TgMIC13, numerous proteins are known to act on the surface of T. gondii and might as well contribute to the phenomenon of promiscuous host cell invasion. In particular, proteins containing coccidian-specific domains other than MAR should be considered. Interestingly, the apple domain, present in TgMIC4, is specific to coccidians (45), although a divergent fold belonging to the plasminogen apple nematode superfamily is present in apical membrane antigen-1 homologues from all Apicomplexans (46, 47). Furthermore, our BLAST searches indicate that the chitin binding-like domain is restricted to coccidians. The chitin binding-like domain is present in TgMIC3 and TgMIC8, which form another major complex involved in invasion. Dimerization of these chitin binding-like domains allows host cell binding and has been associated with parasite virulence (13, 48). Intriguingly, a synergy effect has been demonstrated between this complex and TgMIC1-4-6 (13). However, for most protein complexes functioning in invasion, the timing and coordination of action are only beginning to be understood. In summary our work provides detailed insights into recognition of a broad host cell range by cyst-forming enteroparasites during early stages of invasion and raises the possibility that glycomimetic drugs might be useful to reduce parasite burden in tissues during acute infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Cherbuliez and N. Klages for excellent technical assistance; N. Jemmely for the generation of the anti-TgAMA-1 antibodies; W. Chai and Y. Zhang for mass spectrometric analyses of oligosaccharide probes; R. Childs for the microarrays; and M. P. Stoll for the microarray analyses software. We thank Dr. C. Rodriguez (University of Oviedo), Dr. F. Tomley (Institute for Animal Health, Compton), and Dr. A. Hemphill (University of Bern) for kindly providing us with the C6 rat glioma cell line, CHO cells, and NcMIC1 cDNA, respectively. We also thank M. Messer and T. Urashima for the 4-O-acetylated sialyllactose used in the microarray analyses. We also acknowledge Dr. A. Pain and Dr. A. Reid (Sanger Institute, Hinxton, UK) for integrating our gene models into public data bases.

This work was supported in part by the Swiss National Foundation (to D. S.), the UK Medical Research Council, and UK Research Council Basic Technology Grant GR/S79268 and Translational Grant EP/G037604/1 (to T. F.). This work is part of the activities of the BioMalPar European Network of Excellence supported by a European Grant LSHP-CT-2004-503578 from the Priority 1 “Life Sciences, Genomics, and Biotechnology for Health” in the 6th Framework Programme.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Materials and Methods, Figs. S1–S7, and Tables I and II.

M. S. Stoll, unpublished data.

N. Friedrich, J. Santos, and D. Soldati-Favre, unpublished data.

- Sia

- sialic acid

- EGF

- epidermal growth factor

- ESA

- excreted secreted antigens fraction

- HFF

- human foreskin fibroblast

- MAR

- microneme adhesive repeat

- MCP

- MAR-containing protein

- MIC

- microneme protein

- NANA

- N-acetylneuraminic acid

- 3′SiaLacNAc

- 3′sialyl-N-acetyllactosamine

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- CHO

- Chinese hamster ovary

- IFA

- immunofluorescence assay

- WT

- wild type

- EST

- expressed sequence tag

- SP

- signal peptide.

REFERENCES

- 1.Blumenschein T. M., Friedrich N., Childs R. A., Saouros S., Carpenter E. P., Campanero-Rhodes M. A., Simpson P., Chai W., Koutroukides T., Blackman M. J., Feizi T., Soldati-Favre D., Matthews S. (2007) EMBO J. 26, 2808–2820 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persson K. E., McCallum F. J., Reiling L., Lister N. A., Stubbs J., Cowman A. F., Marsh K., Beeson J. G. (2008) J. Clin. Invest. 118, 342–351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sim B. K., Orlandi P. A., Haynes J. D., Klotz F. W., Carter J. M., Camus D., Zegans M. E., Chulay J. D. (1990) J. Cell Biol. 111, 1877–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takabatake N., Okamura M., Yokoyama N., Ikehara Y., Akimitsu N., Arimitsu N., Hamamoto H., Sekimizu K., Suzuki H., Igarashi I. (2007) Vet. Parasitol. 148, 93–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin M. J., Rayner J. C., Gagneux P., Barnwell J. W., Varki A. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 12819–12824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montoya J. G., Liesenfeld O. (2004) Lancet 363, 1965–1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carruthers V. B., Sibley L. D. (1997) Eur. J. Cell Biol. 73, 114–123 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soldati-Favre D. (2008) Parasite 15, 197–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carruthers V., Boothroyd J. C. (2007) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carruthers V. B., Tomley F. M. (2008) Subcell. Biochem. 47, 33–45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brecht S., Carruthers V. B., Ferguson D. J., Giddings O. K., Wang G., Jakle U., Harper J. M., Sibley L. D., Soldati D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4119–4127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reiss M., Viebig N., Brecht S., Fourmaux M. N., Soete M., Di Cristina M., Dubremetz J. F., Soldati D. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 152, 563–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cérède O., Dubremetz J. F., Soête M., Deslée D., Vial H., Bout D., Lebrun M. (2005) J. Exp. Med. 201, 453–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meissner M., Reiss M., Viebig N., Carruthers V. B., Toursel C., Tomavo S., Ajioka J. W., Soldati D. (2002) J. Cell Sci. 115, 563–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saouros S., Edwards-Jones B., Reiss M., Sawmynaden K., Cota E., Simpson P., Dowse T. J., Jäkle U., Ramboarina S., Shivarattan T., Matthews S., Soldati-Favre D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 38583–38591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawmynaden K., Saouros S., Friedrich N., Marchant J., Simpson P., Bleijlevens B., Blackman M. J., Soldati-Favre D., Matthews S. (2008) EMBO Rep. 9, 1149–1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huynh M. H., Opitz C., Kwok L. Y., Tomley F. M., Carruthers V. B., Soldati D. (2004) Cell. Microbiol. 6, 771–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carruthers V. B., Håkansson S., Giddings O. K., Sibley L. D. (2000) Infect. Immun. 68, 4005–4011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Monteiro V. G., Soares C. P., de Souza W. (1998) FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 164, 323–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortega-Barria E., Boothroyd J. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 1267–1276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gubbels M. J., Li C., Striepen B. (2003) Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 309–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palma A. S., Feizi T., Zhang Y., Stoll M. S., Lawson A. M., Díaz- Rodríguez E., Campanero-Rhodes M. A., Costa J., Gordon S., Brown G. D., Chai W. G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 5771–5779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia D., Sanderson S. J., Jones A. R., Prieto J. H., Yates J. R., Bromley E., Tomley F. M., Lal K., Sinden R. E., Brunk B. P., Roos D. S., Wastling J. M. (2008) Genome Biol. 9, R116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keller N., Naguleswaran A., Cannas A., Vonlaufen N., Bienz M., Björkman C., Bohne W., Hemphill A. (2002) Infect. Immun. 70, 3187–3198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Labbé M., de Venevelles P., Girard-Misguich F., Bourdieu C., Guillaume A., Péry P. (2005) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 140, 43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deutscher S. L., Nuwayhid N., Stanley P., Briles E. I., Hirschberg C. B. (1984) Cell 39, 295–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esko J. D., Rostand K. S., Weinke J. L. (1988) Science 241, 1092–1096 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Feizi T., Chai W. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 582–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garnett J. A., Liu Y., Leon E., Allman S. A., Friedrich N., Saouros S., Curry S., Soldati-Favre D., Davis B. G., Feizi T., Matthews S. (2009) Protein Sci. 18, 1935–1947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y., Feizi T., Campanero-Rhodes M. A., Childs R. A., Zhang Y., Mulloy B., Evans P. G., Osborn H. M., Otto D., Crocker P. R., Chai W. (2007) Chem. Biol. 14, 847–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasegawa A., Ogawa H., Kiso M. (1992) Carbohydr. Res. 224, 185–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fox B. A., Ristuccia J. G., Gigley J. P., Bzik D. J. (2009) Eukaryot. Cell 8, 520–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huynh M. H., Carruthers V. B. (2009) Eukaryot. Cell 8, 530–539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iwersen M., Dora H., Kohla G., Gasa S., Schauer R. (2003) Biol. Chem. 384, 1035–1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinninger A., Richet C., Pons A., Kohla G., Schauer R., Bauer H. C., Zanetta J. P., Vlasak R. (2006) Glycoconj. J. 23, 73–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matrosovich M. N., Gambaryan A. S., Chumakov M. P. (1992) Virology 188, 854–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Messer M. (1974) Biochem. J. 139, 415–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inoue S., Poongodi G. L., Suresh N., Jennings H. J., Inoue Y. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 8541–8546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fukuda M. N., Dell A., Oates J. E., Fukuda M. (1985) J. Biol. Chem. 260, 6623–6631 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Orlandi P. A., Klotz F. W., Haynes J. D. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 116, 901–909 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tolia N. H., Enemark E. J., Sim B. K., Joshua-Tor L. (2005) Cell 122, 183–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ellison S. P., Greiner E., Dame J. B. (2001) Vet. Parasitol. 95, 251–261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hemphill A., Vonlaufen N., Naguleswaran A. (2006) Parasitology 133, 261–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moire N., Dion S., Lebrun M., Dubremetz J. F., Dimier-Poisson I. (2009) Exp. Parasitol. 123, 111–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Z., Harb O. S., Roos D. S. (2008) PLoS One 3, e3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chesne-Seck M. L., Pizarro J. C., Vulliez-Le Normand B., Collins C. R., Blackman M. J., Faber B. W., Remarque E. J., Kocken C. H., Thomas A. W., Bentley G. A. (2005) Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 144, 55–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pizarro J. C., Vulliez-Le Normand B., Chesne-Seck M. L., Collins C. R., Withers-Martinez C., Hackett F., Blackman M. J., Faber B. W., Remarque E. J., Kocken C. H., Thomas A. W., Bentley G. A. (2005) Science 308, 408–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cérède O., Dubremetz J. F., Bout D., Lebrun M. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 2526–2536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.