Abstract

Background:

Asymmetric methylarginines inhibit nitric oxide (NO) synthase (NOS) activity and thereby decrease NO production. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1 (DDAH1) degrades asymmetric methylarginines. We previously demonstrated that in the heart DDAH1 is predominantly expressed in vascular endothelial cells. Since an earlier study showed that mice with global DDAH1 deficiency was embryonic lethal, we speculate that a mouse strain with selective vascular endothelial DDAH1 deficiency (endo-DDAH1−/−) would largely abolish tissue DDAH1 expression in many tissues but possibly avoid embryonic lethality.

Methods and Results:

By using the LoxP/Cre approach, we generated the endo-DDAH1−/− mice. The endo-DDAH1−/− mice had no apparent defect in growth or development as compared with wild type littermates. DDAH1 expression was greatly reduced in kidney, lung, brain, and liver, indicating that in these organs DDAH1 is mainly distributed in vascular endothelial cells. The endo-DDAH1−/− mice showed a significant increase of asymmetric methylarginine concentration in plasma (1.41μM in the endo-DDAH1−/− vs. 0.69μM in the control mice), kidney, lung and liver, which was associated with significantly increased systolic blood pressure (132 mmHg vs. 113 mmHg in wild type). The endo-DDAH1−/− mice also exhibited significantly attenuated acetylcholine-induced NO production and vessel relaxation in isolated aortic rings.

Conclusion:

Our study demonstrates that DDAH1 is highly expressed in vascular endothelium, and that endothelial DDAH1 plays an important role in regulating blood pressure. In the context that asymmetric methylarginines are broadly produced by many type of cells, the strong DDAH1 expression in vascular endothelium demonstrates for the first time that vascular endothelium can be an important site to actively dispose of toxic biochemical molecules produced by other types of cells.

Keywords: Asymmetric dimethylarginine, dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1, nitric oxide, gene knockout mice

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) produced by NO synthases (NOS) exerts many important biological functions. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) and NG-monomethylarginine (L-NMMA) are endogenous NOS inhibitors that competitively inhibit NO production. Recent reports have demonstrated that accumulation of asymmetric methylarginines is a major risk factor for cardiovascular diseases including hypertension 1, 2, congestive heart failure 3, 4, stroke 5, coronary heart disease 6, atherosclerosis 7 and diabetes 8.

ADMA and L-NMMA are eliminated principally by metabolism to L-citrulline by the enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) 9, 10, with a small contribution from renal excretion 11. Two isoforms of DDAH have been identified, DDAH1 12 and DDAH2 13. Overexpression of either DDAH1 or DDAH2 in transgenic mice led to decreased plasma ADMA levels, increased NO bioavailability, and decreased blood pressure 14, 15. Conversely, global heterozygous DDAH1 gene deficiency or treatment of wild type mice with selective DDAH inhibitors resulted in decreased acetylcholine-induced NO production and vasodilation in aortic rings16. This study also showed that homozygous global DDAH1 gene deletion in mice was lethal in utero, and that the total DDAH activity of lung, liver and kidney was significantly decreased in heterozygous DDAH1 deficient mice 16. It was reported that the distribution of DDAH1 is similar to nNOS, while the distribution of DDAH2 is similar to eNOS, suggesting that DDAH1and DDAH2 are mainly expressed in neuronal tissue and vascular endothelium, respectively 17. However, we recently found that DDAH1 is highly expressed in vascular endothelial cells in hearts 18, which is consistent with another early report showing strong DDAH1 expression in renal vascular endothelial cells 19.

Here, using LoxP/Cre strategy, we have generated homologous vascular endothelial specific DDAH1 gene deficient (endo-DDAH1−/−) mice. The endo-DDAH1−/− mice had significantly increased plasma ADMA levels, decreased acetylcholine-induced NO production and vessel relaxation in isolated vessel rings, and elevation of systolic blood pressure, indicating that vascular endothelial DDAH1 regulates NO bioavailability and vessel tone. Most interestingly, we found that DDAH1 expression was greatly reduced in tissues obtained from liver, lung, aorta, brain, skeletal muscle, and kidney in some of the endo-DDAH1−/− mice, indicating that in these organs DDAH1 is predominantly expressed in vascular endothelial cells. In the context that asymmetric methylarginines are produced by all kinds of cells, the strong expression of DDAH1 in endothelium indicates that vascular endothelial cells represent the important site for removal of asymmetric methylarginines. Since vascular endothelial cells actively take up asymmetric methylarginines, this distribution of DDAH1 in the endothelial cells suggests that the vascular endothelium not only produces biological molecules that regulate functions of other cells, but also contributes to disposing of metabolic byproducts generated by other cells, a biological function previously unknown for the endothelium.

Material and Methods

Generation of endo-DDAH1−/− mice

The genomic DNA of DDAH 1 was amplified by PCR, subcloned into pGEM-Teasy vector (Promega) and confirmed by DNA sequencing. The targeting vector was constructed as shown in Figure 1A and introduced into CJ7 ES cells by electroporation. Homologous recombinant clones were identified by Southern blot (Figure 1B), and two independent clones were used to generate chimeras with C57BL/6J blastocysts. The heterozygous DDAHflox/+ were obtained by inbreeding the male chimeras with female C57BL/6J and identified by Southern blot and PCR using primer pairs 5′- AAT CTG CAC AGA AGG CCC TCA A-3′/ 5′- TTC TGA ATC CCA GCC GTC TGA A and 5′- AGG ATG ATC TGG ACG AAG AGC A-3′/5′- TTC TGA ATC CCA GCC GTC TGA A-3′ to identify wild type allele and floxed allele, respectively. The endothelial specific DDAH1 knockout mice were generated by crossing DDAH1flox/+ with Tie2-Cre transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory, B6.Cg-Tg (Tek-cre)12Flv/J). The endo-DDAH1−/− (DDAH1flox/flox/Tie2-Cre) was genotyped by PCR using the primer pairs listed above to identify DDAH1flox/flox and primer pair 5′-GCG GTC TGG CAG TAA AAA CTA TC-3′/5′- GTG AAA CAG CAT TGC TGT CAC TT-3′ to identify mice with Tie2-Cre. The deletion of DDAH1 exon 4 was confirmed by PCR using primer pair 5′-TGT CCA CAA GGG ATG CAA ACA-3′/5′- AAG CCC ATT GTG AAG TAG-3′. The disruption of DDAH1 expression was confirmed by Western blot.

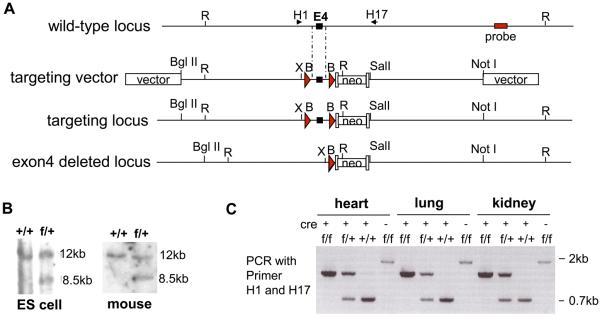

Figure1.

Generation of endo-DDAH1−/− mice. (A) Targeting strategy. A restriction map of the relevant genomic DNA of DDAH1 gene, the targeting vector, the targeted locus after recombination, and the exon 4 deleted locus are shown. neo, neomycine resistance gene; arrowheads, LoxP sites; R, EcoRI; B, BamHI; X, XhoI. (B) Southern blot of wild type and targeted alleles. Genomic DNA was prepared from ES cell and mice and digested with EcoR I. The 12kb and 8.5kb bands represent wild type and targeted allele, respectively. (C) The genotyping by PCR using primer pair H1 and H17 (as indicated in Figure 1A). The PCR products were 0.7kb, 1.3kb and 1.8kb for the wild type, the exon 4 deleted allele and exon 4 floxed allele, respectively.

Western blot

Tissue samples were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen after collection. Proteins from tissue homogenates were separated on SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to PVDF nitrocellulose membranes. The primary antibody against DDAH1 was developed in our laboratories 18. DDAH2 antibody was from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. The horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (BioRad) were detected with enhanced chemiluminescent substrate (Amersham).

Determination of plasma and tissue ADMA levels

Plasma ADMA levels were determined by a validated ELISA method 20 (DLD Diagnostika GmbH, Hamburg, Germany). Tissue ADMA and SDMA concentrations were determined as previously described 21.

Echocardiography

Mice were anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane. Echocardiographic images were obtained with a Visualsonics Veve 770 system as previously described 22.

Evaluation of blood pressure and LV hemodynamics

Invasive hemodynamic studies were performed as previously described 23. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane, incubated using a 24G catheter and ventilated with a mouse ventilator (HSE Harvard Apparatus). The ventilation rate was set at 120 breaths/min with a tidal volume of 250-300 μl. The anesthesia was maintained with 2% isoflurane. For the hemodynamic measurement, a 1.2 Fr. pressure catheter (Scisense Inc. Ontario Canada) was introduced into the right common carotid artery for aortic pressure measurement and then advanced into left ventricle (LV) for measurement of LV pressure, its first derivative (LV dP/dt), and heart rate. Data represent the mean of at least 10 beats of recording during stable hemodynamic conditions. Tail blood pressure was determined in conscious mice with the XBP 1000 system (Kent Scientific).

Measurement of NO production and vessel relaxation

Cross sections of aorta (~2mm) were incubated with 10μM NO-specific fluorescent probe 4, 5-diaminofluoresceine diacetate (DAF-2 DA) (Sigma) dye and 100 μM L-arginine (Sigma) at 37μC for 30 minutes and then washed with DPBS to remove free dye. For those sections treated with L-NAME, 100 μM L-NAME was added during the last 20 minutes of DAF-2 DA incubation and no L-arginine was added. For measurement of NO production, DAF-2 was excited at a wavelength of 490nm with an emitted fluorescence at 515nm. The fluorescence was captured by an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope. The signal intensity was recorded every 10 seconds for 5 minutes for each study.

For measuring vessel relaxation, mouse thoracic aortic rings were mounted in myographs (in PSS buffer bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2 at 37 μC) at 0.25g resting tension. Vessels were then contracted with 10−7 M phenylephrine (PE) as previously described 24. After the vessel contraction was stabilized, acetylcholine or sodium nitroprusside were added at indicated doses.

Data Analysis

Values are expressed as mean±SEM. At least four animals from each group were used for each study. Unpaired student t tests were performed to compare endo-DDAH1−/− mice with their littermate controls. For the study of acetylcholine induced NO production in isolated aortic rings, three-way repeated measures ANOVA was used. Two-way repeated measures ANOVA was used for the study of acetylcholine induced vessel dilation in aortic rings. If the ANOVA demonstrated a significant effect, post hoc comparisons were made pairwise with Fisher's least significant difference test. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Endothelium-specific deletion of DDAH1 gene

The targeting vector was generated by inserting DDAH1 genomic DNA into pflox-FRT-Neo vector (Figure 1A) 25. Two loxP sites were introduced into the 3rd and 4th intron of DDAH1 gene. The targeting vector was linearized with Not I before transfection into CJ7 ES cells by electroporation. The homologous recombinant clones were identified by Southern blot (Figure 1B) and injected into blastocysts from C57BL/6J mice to generate chimeras. The male chimeras were inbred with female C56BL/6J and germ-line transmitted heterozygous mice DDAH1flox/+ were identified by Southern blot (Figure 1B). The DDAH1flox/+ mice were crossed with Tie2-Cre transgenic mice (Jackson Laboratory, B6.Cg-Tg (Tek-cre)12Flv/J) that have endothelium-specific expression of Cre. The double heterozygous DDAH1flox/+/Tie2-Cre were identified by PCR, and further inbred with DDAH1flox/+/Tie2-Cre or crossed with DDAH1flox/+ to generate DDAH1flox/flox/Tie2-Cre. Three types of control mice were generated from this breeding: DDAH1flox/flox, DDAH1+/+/Tie2-Cre, and DDAH1+/+. There were no significant differences in terms of DDAH1 protein level, LV function, blood pressure, heart rate, and ratio of heart weight to body weight (data not shown) among these three control mice. Therefore, in the following studies, DDAH1flox/flox/Tie2-Cre were crossed with DDAH1flox/flox to generate DDAH1flox/flox/Tie2-Cre (endo-DDAH1−/−), and their DDAH1flox/flox littermates were used as controls.

The endo-DDAH1−/− mice were viable and grew and developed normally. The endo-DDAH1−/− mice were viable and grew and developed normally. PCR using primers surrounding exon 4 showed that exon 4 was deleted in heart, lung and kidney of endo-DDAH1−/− mice (Figure 1C). Since the amplification of the exon 4-floxed allele (~1.8kb PCR product) is less efficient than the amplification of exon 4-deleted allele (~1.3kb PCR product), only the exon 4-deleted allele could be detected by PCR of endo-DDAH1−/− genomic DNA (supplemental Figure S1).

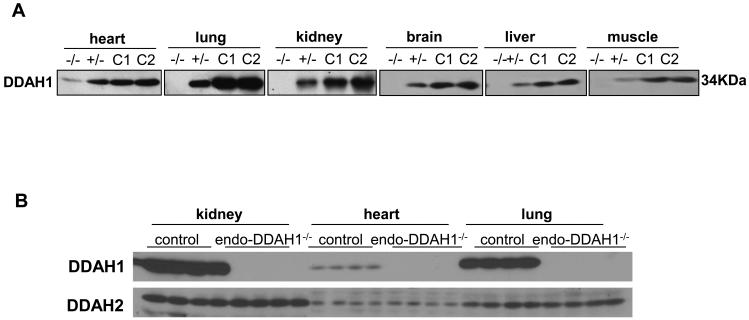

Endothelium-specific deletion of the DDAH1 gene greatly reduces the expression of DDAH1 in several organs

While the expression levels of DDAH1 among different organs were dramatically different, Western blot with DDAH1 specific antibody detected almost no DDAH1 protein expressed in lung, kidney, brain, liver, and skeletal muscle (Figure 2A) of the endo-DDAH1−/− mice. After prolonged exposure, small amount of DDAH1 could be detected in the endo-DDAH1−/− heart (Figure 2A) and aorta (supplemental Figure S2). The amount of DDAH1 in the heterozygous DDAHflox/+/Tie2-Cre mice in these organs was about 50% of control (Figure 2A). This result suggested that DDAH1 is highly expressed in endothelium of these organs.

Figure 2.

The expression of DDAH1 and DDAH2 in the endothelial specific DDAH1 knockout mice. In order to show the relative decrease of DDAH1 expression in various organs of the endo-DDAH1−/− mice, different amounts of total tissue lysate were loaded for different organs and the exposure times of different Western blots were varied (A). The protein levels of DDAH2 were not changed in heart, lung and kidney in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice (B). −/−: homozygote for endothelial specific DDAH1 knockout mice (endo-DDAH1−/−); +/−: heterozygote for endothelial specific DDAH1 knockout mice (endo-DDAH1+/−); C1: wild type control mice, with Tie2-Cre expression; C2: DDAH1flox/flox control mice.

Endothelium-specific deletion of DDAH1 gene has no effect on DDAH2 expression

To determine whether endothelial DDAH1 gene deletion would cause compensatory upregulation of DDAH2 expression, the protein content of DDAH2 was determined in several organs of endo-DDAH1−/− mice. As shown in Figure 2B, the protein levels of DDAH2 in the endo-DDAH1−/− heart, lung and kidney was not significantly different from control, indicating that depletion of DDAH1 in endothelium did not affect the expression of DDAH2 in these organs.

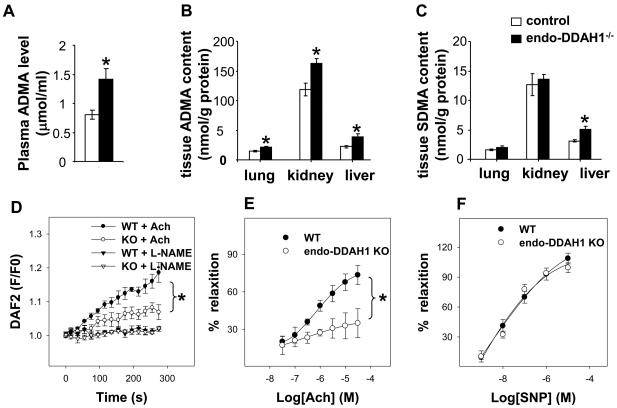

Endo-DDAH1−/− increases ADMA levels in plasma, kidney, lung and liver, and reduces acetylcholine-induced NO generation and vasodilation in aortic rings

With the depletion of DDAH1 in the endothelium, plasma ADMA levels in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice were more than 75% higher than in the control mice (1.41 μmol/l in endo-DDAH1−/− mice vs. 0.69 μmol/l in the control mice, p<0.05, Figure 3A). In addition, the ADMA content in lung, liver and kidney was significantly higher in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice as compared with control (Figure 3B), suggesting that endothelial DDAH1 plays a pivotal role not only in clearing circulating ADMA, but also in degrading ADMA in these organs. The SDMA content was not different between the endo-DDAH1−/− and control mice in lung and kidney. In liver, however, SDMA was significantly increased by ~60% in the endo-DDAH1−/− as compared with control (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Endothelial specific DDAH1 knockout led to increased ADMA level in plasma (A) (n=9 samples each group); as well as in kidney, lung and liver (B) (n=4-5 samples each group). In the DDAH1−/− mice, the SDMA level was not changed in lung and kidney, but significantly increased in the liver (C), (n=4-5 samples each group). The endo-DDAH1−/− aortic rings had reduced acetylcholine-induced NO generation (D) (n=6-8 samples each group) and acetylcholine-induced vessel relaxation (E), but relaxation in response to nitroprusside was not affected (F) (n=7-10 samples each conditions).

To determine if the increased ADMA level influences NO availability, we measured NO generation in response to acetylcholine stimulation in isolated aortic rings using DAF-2 DA. Endothelial specific deletion of DDAH1 gene attenuated acetylcholine-induced NO production in the aortic rings derived from the endo-DDAH1−/− mice, while 1mM of L-NAME almost completely blocked the acetylcholine-induced NO generation from both control and endo-DDAH1−/− aortic rings (Figure 3D). These data demonstrate that disruption of endothelial DDAH1 impairs acetylcholine induced NO generation. In addition, the endo-DDAH1−/− significantly reduced aortic ring relaxation in response to acetylcholine, but had no effect on their relaxation in response to NO donor sodium nitroprusside (Figure 3E and 3F).

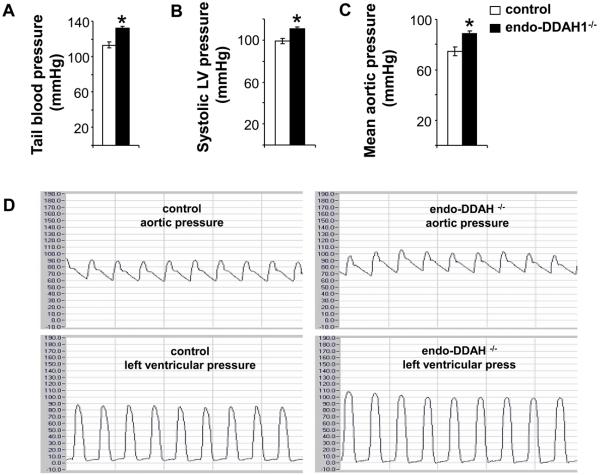

Endo-DDAH1−/− mice have increased blood pressure

To determine whether vascular endothelial DDAH1 is involved in regulating vascular tone, blood pressure was evaluated in both conscious mice and mice during anesthesia. Measured in conscious state by tail-cuff method, the endo-DDAH1−/− mice exhibited significantly increased systemic blood pressure (132 ±2 mmHg in the endo-DDAH1−/− vs.113±3 mmHg in the control mice) (Figure 4A). Invasive hemodynamic studies showed that both the systolic blood pressure (endo-DDAH1−/− 110±2 mmHg vs. control 99±3 mmHg, Figure 4B and 4D) and the mean aortic pressure (endo-DDAH1−/− 89±2 mmHg vs. control 75±3mmHg, Figure 4C and 4D) were significantly higher in endo-DDAH1−/− mice than their control littermates. Vascular resistances were calculated using blood pressure (tail-cuff method) and the cardiac output. The result showed that vascular resistance (endo-DDAH1−/− 5.06±0.36 mmHg/ml/min vs. control 3.67 ±0.45 mmHg/ml/min) was significantly increased in endo-DDAH1−/− mice.

Figure 4.

The endo-DDAH1−/− mice had increased tail blood pressure (A), systolic left ventricular pressure (B), mean aortic pressure (C, D). The representative aortic and left ventricular pressure recordings (D). *<0.05 as compared to DDAH1flox/flox controls. Mean value was obtained from 8-10 samples each group.

Endo-DDAH1−/− mice have normal ventricular size and function at 3-months of age

Aortic and left ventricular (LV) systolic pressures were significantly increased in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice (Figure 4B and 4C). Despite this significant increase of blood pressure, cardiac structure and function of the young endo-DDAH1−/− mice remained normal as compared with control littermates. There was a trend toward an increase in the ratios of heart weight, LV weight, right ventricular weight, as well as lung weight to tibial length in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice. However, none of these changes were statistically significant. LV ejection fraction and dimensions were not significantly different between control and the endo-DDAH1−/− mice. Taken together, at 3-months of age, the endo-DDAH1−/− mice had not developed LV hypertrophy or dysfunction. However, DDAH1 depletion may cause subtle changes in the cardiac structure and functions.

Discussion

The significant findings of this study are: (i) endo-DDAH1−/− greatly reduced DDAH1 expression in organs such as lung, liver, kidney and brain etc; (ii) endo-DDAH1−/− causes an increase of the endogenous NOS inhibitor ADMA in plasma, kidney, liver and lung; (iii) endo-DDAH1−/− mice have increased systemic blood pressure, and (iv) endo-DDAH1−/− has no significant impact on growth and development, or on cardiac function in young mice.

Since asymmetric methylarginines are produced by almost all type of cells and broadly inhibit all three NOS isoforms, the endo-DDAH1−/− and the DDAH1flox/flox mice are anticipated to be useful tools for the study of DDAH1 and asymmetric methylarginines in the development of clinical complications such as hypertension, diabetes and congestive heart failure. These strains may be particularly useful for study of tissue-specific NO bioavailability in various organs under physiological or pathological conditions.

It is well known that the endothelium regulates many biological and physiological functions including the control of vascular tone, leukocyte and biomolecule trafficking, cell growth and proliferation/angiogenesis, and inflammatory responses. However, it was not previously known that vascular endothelium can play an important role in removing toxic biochemical molecules. Our findings that endothelial specific DDAH1 gene deletion reduced DDAH1 expression in all organs tested and increased plasma and tissue ADMA levels demonstrate that the vascular endothelium has a unique function to dispose of asymmetric methylarginines produced in other tissues. In addition, it is perceivable that the strategic distribution of DDAH1 in vascular endothelium would benefit endothelial cells by degrading the endogenous NOS inhibitors and promoting local eNOS activity and NO production.

The elevated ADMA level in the endo-DDAH1−/− is associated with a moderate increase of systemic blood pressure in these mice. This moderate increase of blood pressure in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice essentially duplicates the phenotype observed in young eNOS knockout mice 26. Reports from several clinical studies showed that ADMA levels increase in the patients with hypertension 27-29. Thus, decreased DDAH activity and accumulation of ADMA may have a causal relationship with hypertension. Furthermore, endo-DDAH1−/− impairs acetylcholine-induced NO production and vasodilation in the isolated aortic rings. Studies using selective DDAH inhibitors or in the heterozygous global DDAH1 null mice showed similar results 16. These data suggest that DDAH1 is critical in ADMA clearance, endothelium dependent vasodilation and maintenance of normal blood pressure.

In some of the endo-DDAH1−/− mice, DDAH1 expression was almost undetectable in many organs. In the context that a previous study showed that global homozygous DDAH1 is lethal at the embryonic stage 16, the finding that depletion of DDAH1 has no significant effects on growth and development is unanticipated. As the expression of Tek/Tie2 is detectable at around embryonic day 8.0 (E8 .0) in the mouse 30 31, while the expression of DDAH1 seems to be important in trophoblast invasion and embryo implantation 32 (which takes place during E4-6 in most laboratory rodents 33), one potential explanation for the discrepancy might be that DDAH1 expression is required by some biological processes before the Tie2 promoter becomes active during embryogenesis. Therefore, DDAH1 expression is not indispensable for embryonic development after Tie2 expression occurs. Alternatively, the construct from the previous global DDAH1−/− may exert some unwanted effects in addition to the deletion of DDAH1 gene. Another possible explanation might be that DDAH1 expression is not totally abolished in our tissue specific DDAH1−/− strain. Thus, the residual DDAH1, particular the DDAH1 expressed in non-endothelial cells, may be critical for the survival and early development of embryos. Further studies are needed to address this question.

DDAH1 protein is highly expressed in kidney, liver, brain, and lung. Kidney and liver are reported to be the two organs that have the highest capacity for ADMA uptake and clearance 34. We found that kidney had the highest free ADMA of all organs tested, and that endothelial specific DDAH1 deletion caused significant ADMA accumulation in both kidney and liver. We also observed a significant 45% increase of pulmonary ADMA in the endo-DDAH1−/−. Overall, these results suggest that DDAH1 is essential in regulating ADMA levels in these organs. The long-term physiological impact of increased ADMA levels, and consequently decreased NO bioavailability, in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice is yet to be determined. Although SDMA cannot be metabolized by DDAH1, the SDMA content in liver was also significantly increased in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice. Ogawa et al identified a common pathway for degradation of both ADMA and SDMA, through the formation of α-ketoacid analogs and the oxidatively decarboxylated products of the α-ketoacids 35. When the major metabolic route to eliminate ADMA by DDAH1 is not available, increased amounts of ADMA may compete with SDMA for this alternative route for degradation. This could contribute to the elevation of liver SDMA in endo-DDAH1−/− mice.

The cellular distribution of DDAH1 has been a subject of controversy for years. Thus, by using an antibody detecting a protein at ~34KDa, an early study from Tojo et al demonstrated that DDAH1 was strongly expressed in vascular endothelial cells 19. We recently found that DDAH1 was primarily expressed in vascular endothelial cells in hearts 18, and we confirmed the specificity of the antibody used in our study by using selective DDAH1 gene silencing in cultured human endothelial cells. In the present study, we found that endothelial specific DDAH1 gene deletion resulted in greatly reduced DDAH1 protein (at ~34KD) in kidney, liver, lung, skeletal muscle, and brain, and this was accompanied by increased tissue and plasma ADMA levels. Moreover, the Tie2-Cre strain of mouse used in this study has been well defined 36 and studies demonstrated that the regulatory cassette that controls Cre expression in this strain has uniform and specific endothelial specific promoter/enhancer activity at both embryonic and adult stages 36, 37. Thus, our data indicated that DDAH1 is highly expressed in vascular endothelial cells.

However, Western blot analysis in several recent studies idenified a protein at 38~40KDa as DDAH138. By using the same antibody as for the Western blot in their immunohistochemical staining, these studies demonstrated that DDAH1 was also expressed in cell types other than endothelial cells, such as bronchial smooth muscle cells 38, proximal tubules of the nephron 39 and vascular smooth muscle cells 40. Since the antibody used in the above studies is not available to us, we are not sure whether the discrepancy among different groups is due to the inconsistent labeling of protein size of DDAH1 or an issue of antibody specificity. Therefore, the exact cause of the discrepancy regarding DDAH1 distribution is not clear at the present time. Hopefully, the tissue samples from our DDAH1 deficient mice can help to address this question. Moreover, as Western blots may not be able to detect the residual amount of DDAH1 in the whole organ extracts, the data from our study cannot exclude small amount of DDAH1 expressed in cells other than endothelial cells. Indeed, our data demonstrated that DDAH1 was detectable in heart and aorta obtained from endo-DDAH1−/− mice, indicating that DDAH1 is at least also expressed in cardiac myocytes 18 and vascular smooth muscle cells 40.

There are several limitations in the present study. In order to confirm the tissue specific DDAH1 deletion in endo-DDAH1−/− mice, we have made a significant effort to develop antibodies suitable for immunohistochemical staining of DDAH1 in mouse tissues. Unfortunately, we are still currently unable to detect DDAH1 in mouse tissue samples by immunohistochemistry. Therefore, we cannot exclude the possibility that DDAH1 expression might also be disrupted in other type of cells in this endo-DDAH1−/− strain. In addition, although we found that there is no upregulation of DDAH2 in the heart, lung and kidney in the endo-DDAH1−/− mice, we did not determine endothelial DDAH2 expression and the relative contribution of DDAH1 and DDAH2 on endothelial DDAH activity in these mice. These are the limitations of this study. Furthermore, Tie2 expressing endothelial progenitor cells may theoretically differentiate into non-endothelial cell types that have little or no Tie2 expression at later developmental or adult stages. Thus, even though a differentiated cell may have no Tie2 promoter activity (or cre expression), the DDAH1 gene may have been deleted in their precursor cells prior to diffrentiation. Therefore, though Tie2-Cre mice have uniform and specific endothelial specific promoter/enhancer activity; we could not totally exclude the possibility of DDAH1 gene deletion in cell types other than vascular endothelial cells. This is the limitation of using Tie2-Cre strain to generate endothelial specific gene deficient strains.

In summary, our present study demonstrates that DDAH1 is greatly reduced in several organs in the endo-DDAH1−/− strain, indicating that vascular endothelium is an important site for removal of toxic asymmetric methylarginines. In addition, we found that endo-DDAH1−/− mice have increased plasma and tissue ADMA levels and blood pressure, indicating that vascular DDAH1 plays an important role in regulating NO bioavailability and blood pressure. Our study also suggests that DDAH1 expression may not be indispensible for embryonic development after Tie2 expression occurs. Finally, the DDAH1flox/flox and endo-DDAH1−/− mouse strains could be of considerable utility for studies of NO bioavailability in many physiological and pathological conditions, possibly in a tissue-specific fashion.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledge

The endo-DDAH1−/− mouse strain was developed with the help from University of Minnesota's Mouse Genetics Laboratory. We thank Dr. Haoyu Yu for her assistance with statistical data analysis.

Sources of Funding: This study was supported by NHLBI Grants HL71790 (YC) and HL21872 (RJB) from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Xu is a recipient of an American Heart Association Postdoctoral fellowship. Drs. Hu and Zhang are recipients of Scientist Development Award from AHA National Center.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflicts declared.

References

- 1.Gorenflo M, Zheng C, Werle E, Fiehn W, HE U. Plasma levels of asymmetrical dimethyl-L-arginine in patients with congenital heart disease and pulmonary hypertension. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 2001;37:498–492. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200104000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Surdacki A, Nowicki M, Sandmann J, Tsikas D, Boeger RH, Bode-Boeger SM, Kruszelnicka-Kwiatkowska O, Kokot F, Dubiel JS, JC F. Reduced urinary excretion of nitric oxide metabolites and increased plasma levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine in men with essential hypertension. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology. 1999;33:652–658. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199904000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saitoh M, Osanai T, Kamada T, Matsunaga T, Ishizaka H, Hanada H, Okumura K. High plasma level of asymmetric dimethylarginine in patients with acutely exacerbated congestive heart failure: role in reduction of plasma nitric oxide level. Heart and Vessels. 2003;18:177–182. doi: 10.1007/s00380-003-0715-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Usui M, Matsuoka H, Miyazaki H, Ueda S, Okuda S, Imaizumi T. Increased endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitor in patients with congestive heart failure. Life Sciences. 1998;62:2425–2430. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(98)00225-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wanby P, Teerlink T, Brudin L, Brattstrom L, Nilsson I, Palmqvist P, Carlsson M. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) as a risk marker for stroke and TIA in a Swedish population. Atherosclerosis. 2006;185:271–277. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schulze F, Lenzen H, Hanefeld C, Bartling A, Osterziel KJ, Goudeva L, Schmidt-Lucke C, Kusus M, Maas R, Schwedhelm E, Strodter D, Simon BC, Mugge A, Daniel WG, Tillmanns H, Maisch B, Streichert T, Boger RH. Asymmetric dimethylarginine is an independent risk factor for coronary heart disease: Results from the multicenter Coronary Artery Risk Determination investigating the Influence of ADMA Concentration (CARDIAC) study. American Heart Journal. 2006;152:493.e491–493.e498. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumagai H, Sakurai M, Takita T, Maruyama Y, Uno S, Ikegaya N, Kato A, Hishida A. Association of Homocysteine and Asymmetric Dimethylarginine With Atherosclerosis and Cardiovascular Events in Maintenance Hemodialysis Patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 2006;48:797–805. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2006.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sydow K, Mondon CE, Schrader J, Konishi H, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase Overexpression Enhances Insulin Sensitivity. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:692–697. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.162073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogawa T, Kimoto M, Sasaoka K. Occurrence of a new enzyme catalyzing the direct conversion of NG,NG-dimethyl-L-arginine to L-citrulline in rats. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1987;148:671–677. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)90929-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogawa T, Kimoto M, Sasaoka K. Purification and properties of a new enzyme, NG,NG-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase, from rat kidney. J. Biol. Chem. 1989;264:10205–10209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Achan V, Broadhead M, Malaki M, Whitley G, Leiper J, MacAllister R, Vallance P. Asymmetric Dimethylarginine Causes Hypertension and Cardiac Dysfunction in Humans and Is Actively Metabolized by Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2003;23:1455–1459. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000081742.92006.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimoto M, Miyatake S, Sasagawa T, Yamashita H, Okita M, Oka T, Ogawa T, Tsuji H. Purification, cDNA cloning and expression of human NG,NG-dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase. European Journal of Biochemistry. 1998;258:863–868. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580863.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leiper JM, Santa Maria J, Chubb A, MacAllister RJ, Charles IG, Whitley GS, Vallance P. Identification of two human dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolases with distinct tissue distributions and homology with microbial arginine deiminases. Biochemical Journal. 1999;343:209–214. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dayoub H, Achan V, Adimoolam S, Jacobi J, Stuehlinger MC, Wang B-y, Tsao PS, Kimoto M, Vallance P, Patterson AJ, Cooke JP. Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase Regulates Nitric Oxide Synthesis: Genetic and Physiological Evidence. Circulation. 2003;108:3042–3047. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000101924.04515.2E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasegawa K, Wakino S, Tatematsu S, Yoshioka K, Homma K, Sugano N, Kimoto M, Hayashi K, Itoh H. Role of Asymmetric Dimethylarginine in Vascular Injury in Transgenic Mice Overexpressing Dimethylarginie Dimethylaminohydrolase 2. Circ Res. 2007;101:e2–10. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.156901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiper J, Nandi M, Torondel B, Murray-Rust J, Malaki M, O'Hara B, Rossiter S, Anthony S, Madhani M, Selwood D, Smith C, Wojciak-Stothard B, Rudiger A, Stidwill R, McDonald NQ, Vallance P. Disruption of methylarginine metabolism impairs vascular homeostasis. Nat Med. 2007;13:198–203. doi: 10.1038/nm1543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tran CTL, Fox MF, Vallance P, Leiper JM. Chromosomal Localization, Gene Structure, and Expression Pattern of DDAH1: Comparison with DDAH2 and Implications for Evolutionary Origins. Genomics. 2000;68:101–105. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Li Y, Zhang P, Traverse JH, Hou M, Xu X, Kimoto M, Bache RJ. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase and endothelial dysfunction in failing hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H2212–2219. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00224.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tojo A, Welch WJ, Bremer V, Kimoto M, Kimura K, Omata M, Ogawa T, Vallance P, Wilcox CS. Colocalization of demethylating enzymes and NOS and functional effects of methylarginines in rat kidney. Kidney Int. 1997;52:1593–1601. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schulze F, Wesemann R, Schwedhelm E, Sydow K, Albsmeier J, Cooke JP, Böger RH. Determination of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) using a novel ELISA assay. Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. 2004;42:1377. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2004.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwedhelm E, Maas R, Tan-Andresen J, Schulze F, Riederer U, Böger RH. High-throughput liquid chromatographic-tandem mass spectrometric determination of arginine and dimethylated arginine derivatives in human and mouse plasma. Journal of Chromatography B. 2007;851:211–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang P, Xu X, Hu X, van Deel ED, Zhu G, Chen Y. Inducible Nitric Oxide Synthase Deficiency Protects the Heart From Systolic Overload-Induced Ventricular Hypertrophy and Congestive Heart Failure. Circ Res. 2007;100:1089–1098. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000264081.78659.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van Deel ED, Lu Z, Xu X, Zhu G, Hu X, Oury TD, Bache RJ, Duncker DJ, Chen Y. Extracellular superoxide dismutase protects the heart against oxidative stress and hypertrophy after myocardial infarction. Free Radical Biology and Medicine. 2008;44:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scotland RS, Madhani M, Chauhan S, Moncada S, Andresen J, Nilsson H, Hobbs AJ, Ahluwalia A. Investigation of Vascular Responses in Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase/Cyclooxygenase-1 Double-Knockout Mice: Key Role for Endothelium-Derived Hyperpolarizing Factor in the Regulation of Blood Pressure in Vivo. Circulation. 2005;111:796–803. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000155238.70797.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liang X, Zhou Q, Li X, Sun Y, Lu M, Dalton N, Ross J, Jr., Chen J. PINCH1 Plays an Essential Role in Early Murine Embryonic Development but Is Dispensable in Ventricular Cardiomyocytes. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25:3056–3062. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.8.3056-3062.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang PL, Huang Z, Mashimo H, Bloch KD, Moskowitz MA, Bevan JA, Fishman MC. Hypertension in mice lacking the gene for endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Nature. 1995;377:239–242. doi: 10.1038/377239a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kielstein JT, Bode-Boger SM, Hesse G, Martens-Lobenhoffer J, Takacs A, Fliser D, Hoeper MM. Asymmetrical Dimethylarginine in Idiopathic Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1414–1418. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168414.06853.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takiuchi S, Fujii H, Kamide K, Horio T, Nakatani S, Hiuge A, Rakugi H, Ogihara T, Kawano Y. Plasma asymmetric dimethylarginine and coronary and peripheral endothelial dysfunction in hypertensive patients[ast] Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:802–808. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curgunlu A, Uzun H, Bavunoglu I, Karter Y, Genc H, Vehid S. Increased circulating concentrations of asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA) in white coat hypertension. J Hum Hypertens. 2005;19:629–633. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1001867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dumont DJ, Fong G-H, Puri MC, Gradwohl G, Alitalo K, Breitman ML. Vascularization of the mouse embryo: A study of flk-1, tek, tie, and vascular endothelial growth factor expression during development. Developmental Dynamics. 1995;203:80–92. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamaguchi TP, Dumont DJ, Conlon RA, Breitman ML, Rossant J. flk-1, an flt-related receptor tyrosine kinase is an early marker for endothelial cell precursors. Development. 1993;118:489–498. doi: 10.1242/dev.118.2.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayling LJ, Whitley GSJ, Aplin JD, Cartwright JE. Dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) regulates trophoblast invasion and motility through effects on nitric oxide. Hum. Reprod. 2006;21:2530–2537. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abrahamsohn PA, Zorn TMT. Implantation and decidualization in rodents. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1993;266:603–628. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402660610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bulau P, Zakrzewicz D, Kitowska K, Leiper J, Gunther A, Grimminger F, Eickelberg O. Analysis of methylarginine metabolism in the cardiovascular system identifies the lung as a major source of ADMA. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292:L18–24. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00076.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ogawa T, Kimoto M, Watanabe H, Sasaoka K. Metabolism of NG,NG- and NG,NG-dimethylarginine in rats. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. 1987;252:526–537. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(87)90060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koni PA, Joshi SK, Temann U-A, Olson D, Burkly L, Flavell RA. Conditional Vascular Cell Adhesion Molecule 1 Deletion in Mice: Impaired Lymphocyte Migration to Bone Marrow. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:741–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.6.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schlaeger TM, Bartunkova S, Lawitts JA, Teichmann G, Risau W, Deutsch U, Sato TN. Uniform vascular-endothelial-cell-specific gene expression in both embryonic and adult transgenic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94:3058–3063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Arrigoni FI, Vallance P, Haworth SG, Leiper JM. Metabolism of Asymmetric Dimethylarginines Is Regulated in the Lung Developmentally and With Pulmonary Hypertension Induced by Hypobaric Hypoxia. Circulation. 2003;107:1195–1201. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051466.00227.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Onozato ML, Tojo A, Leiper J, Fujita T, Palm F, Wilcox CS. Expression of NG,NG-Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase and Protein Arginine N-Methyltransferase Isoforms in Diabetic Rat Kidney: Effects of Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers. Diabetes. 2008;57:172–180. doi: 10.2337/db06-1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo Z, Gill PS, Welch W, Jose PA, Wilcox CS. Regulation of Dimethylarginine Dimethylaminohydrolase (DDAH) in Rat Preglomerular Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells (PGVSMCs) by Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) FASEB J. 2008;22:758.724. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.