Abstract

We studied 12 peripheral neuropathy patients (PNP) and 13 age-matched controls with the “broken escalator” paradigm to see how somatosensory loss affects gait adaptation and the release and recovery (“braking”) of the forward trunk overshoot observed during this locomotor aftereffect. Trunk displacement, foot contact signals, and leg electromyograms (EMGs) were recorded while subjects walked onto a stationary sled (BEFORE trials), onto the moving sled (MOVING or adaptation trials), and again onto the stationary sled (AFTER trials). PNP were unsteady during the MOVING trials, but this progressively improved, indicating some adaptation. During the after trials, 77% of control subjects displayed a trunk overshoot aftereffect but over half of the PNP (58%) did not. The PNP without a trunk aftereffect adapted to the MOVING trials by increasing distance traveled; subsequently this was expressed as increased distance traveled during the aftereffect rather than as a trunk overshoot. This clear separation in consequent aftereffects was not seen in the normal controls suggesting that, as a result of somatosensory loss, some PNP use distinctive strategies to negotiate the moving sled, in turn resulting in a distinct aftereffects. In addition, PNP displayed earlier than normal anticipatory leg EMG activity during the first after trial. Although proprioceptive inputs are not critical for the emergence or termination of the aftereffect, somatosensory loss induces profound changes in motor adaptation and anticipation. Our study has found individual differences in adaptive motor performance, indicative that PNP adopt different feed-forward gait compensatory strategies in response to peripheral sensory loss.

INTRODUCTION

The control of locomotion and posture is a multisensory process so that when the support surface becomes unstable, narrow, compliant, or moving, vestibular and visual information become crucial (Buchanan and Horak 1998; Horak et al. 1994; Nasher et al. 1982). In ordinary circumstances, however, somatosensory information from the lower limbs dominates (Dietz 1992; Horak et al. 1990; Magnusson et al. 1990). In agreement, numerous reports have shown the severe consequences that loss of peripheral somatosensory information has on human balance and locomotion (Cavanagh et al. 1992; Dalaska 1986; Dingwell et al. 2000; Griffin et al. 1990; Katoulis et al. 1997; Koski et al. 1998).

While some studies have investigated the role of somatosensory inputs during postural perturbations of standing man (e.g., Allum et al. 1989; Horak et al. 1989; Schieppati and Nardone 1997), other studies have examined perturbations during locomotion (e.g., Cham and Redfern 2002; Marigold and Patla 2002; Pai and Iqbal 1999), but fewer studies have investigated gait adaptation during reduced/absent somatosensory input. However, when peripheral neuropathy patients (PNP) walk on an irregular surface under low light, step length and gait speed is decreased (Thies et al. 2005). Also, on-line adaptation in the soleus muscle during robotically modified walking is decreased (Marazzo et al. 2005; Sinkjaer et al. 2000).

One approach to understanding locomotor adaptation is to examine motor aftereffects because the presence of aftereffects indicates that adaptation has indeed taken place (Lam et al. 2006). Previously, a locomotor aftereffect (LocAE), induced by walking on a moving sled (the “broken escalator” phenomenon Reynolds and Bronstein 2003), was unaffected by the absence of visual and vestibular input (Bunday and Bronstein 2008). We now investigate the influence of reduced somatosensory inputs on the LocAE in a group of patients with PNP. In this aftereffect, subjects approach a stationary platform (previously experienced as moving during the adaptation trials), with increased gait velocity and, once on the stationary platform, they display a forward overshoot of the trunk (illustrated in the cartoon, Fig. 1). Because leg proprioceptive feedback has long been considered critical for triggering and modulating human automatic correcting responses (e.g., Horak et al. 1994; Inglis et al. 1994; Nashner et al. 1982), somatosensory loss in the lower leg may heavily affect moving platform adaptation and aftereffects. If the adaptation process was mediated solely by peripheral feedback, no adaptation would occur and ultimately no LocAE would be seen. As most PNPs suffer from small and large fibre peripheral somatosensory loss, we hypothesize that this aftereffect may be affected in two different ways. The sensation of foot contact with the sled may be critical for the release of the forward trunk sway aftereffect, observed when subjects climb on the stationary surface again (i.e., feeling foot-sled contact may trigger the aftereffect). In this scenario, we would expect PNP to display an impaired or absent trunk overshoot aftereffect. However, if gait aftereffects do occur in PNP, proprioceptive loss may interfere with termination of the aftereffect. This would be the case if leg proprioceptive inputs were involved in arresting the aftereffect, so that it does not result in a stumble or forward fall (i.e., “braking” the forwards trunk overshoot). In general terms, the experiments investigate how somatosensory loss in PNP interferes both with motor adaptation (MOVING trials) and with the release of such adapted motor activity in the form of a motor aftereffect (AFTER trials).

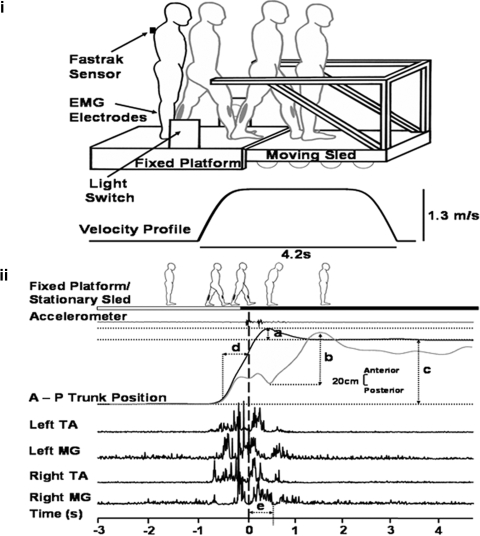

Fig. 1.

Experimental setup and analysis. Top (i): experimental setup showing how the subject walks from the fixed platform with the right leg and landing on the moving sled with the left leg. Note the diagram represents a stationary trial; during moving trials, sled motion will be triggered by the subjects leg passing through the light switch. A Fastrak sensor placed on C7 recorded linear trunk position along the antero-posterior axis. Electromyographic (EMG) electrodes placed on the lower legs recorded muscle activity of tibialis anterior (TA) and medial gastrocnemius (MG). Below the sled diagram, the stimulus velocity profile shows the speed (1.3 m/s) and duration of the sled movement (4.2 s). Bottom (ii): measurements taken: a: trunk (forward) sway (during BEFORE and AFTER trials) measured as the maximum forward deviation of the trunk, relative to the mean final resting stance position in the last 3 s of the trial. b: trunk sway (during MOVING trials) measured as maximum forward deviation of trunk peak to peak. c: distance traveled measured as mean of the starting position in the 1st 3 s relative to the final mean resting stance in the last 3 s of a trial. d: gait velocity as measured in a 0.5 s time window prior to foot contact. e: EMG measured as an integral value from an epoch of 500 ms from initial foot-sled contact (= time 0, vertical broken line).

METHODS

Subjects

Local ethics approval and informed consent for all subjects was obtained. Twelve PNP (7 females) able to walk unaided, age 40–77 yr (mean ± SE 61.8 ± 2.5 yr), were tested. Patients were assessed by an experienced neurologist (AMB) to quantify proximal versus distal weakness and sensory loss, specifically in the lower limbs. This included ankle and knee reflexes, cutaneous sensation (pin-prick disposable neurological needle and cotton wool), and vibration sensation with a quantitative tuning fork (64 Hz) (Bergin et al. 1995). The Romberg test (body sway with eyes open and closed) was considered positive if a moderate/severe increase in unsteadiness was observed on eye closure (and not only as a “true” positive Romberg test, i.e., a fall). All patients suffered from a predominantly distal chronic sensory-motor neuropathy; etiologies included diabetes (6), alcohol induced (2), idiopathic (2), auto-immune/rheumatoid (1), and post Guillian Barre (1). All patients were in a chronic, compensated stage; length of neuropathy was 2–20 yr (mean = 9.2 ± 2.1 yr). Clinical EMG showed that 9 of the 12 PNP presented with mild to moderately severe distal axonal neuropathy; EMG results for the other 3 patients were not available.

Six PNP had minimal ankle weakness in dorsiflexion and plantarflexion of 4+ and 4 in the MRC scale (MRC 1976; range: 0–5, no contraction - normal power, respectively), otherwise knee, hip, lower arm, and finger extension/flexion strength was normal. Indeed, eyes open walking in all patients was clinically normal. Patients with additional neurological features were excluded. An age-matched normal control (NC) group of 13 (6 females) subjects, 43–66 yr (mean age = 57.5 ± 1.7 yr) were also tested. All controls were healthy and reported no history of neurological illness.

Materials

The sled (see Reynolds and Bronstein 2003) was powered by two linear induction motors (maximum velocity = 1.3 m/s; Fig. 1, top). Movement of the sled was triggered by leg motion via an infrared light switch; the sled would travel ∼3.7 m in 4.2 s (maximum velocity reached by 896 ms). A tachometer provided velocity output.

Antero-posterior trunk position with respect to the sled was measured using an electromagnetic tracking device (Fastrak; Polhemus, VT). The sensor was placed over the C7 vertebra and the transmitter was attached to the sled (Fig. 1, top). A second sensor was earth-fixed so that the movement of the sled could be accounted for when calculating approach gait (trunk) velocity and distance traveled. Step timing information was given by pressure sensors (Flexiforce, Teckscan, MA) placed under the first metatarsal phalangeal joint and heel. A sled-mounted linear accelerometer (Entran, Watford, UK) provided independent accurate foot-sled contact timing information. Surface bipolar EMG from the medial gastrocnemius (MG) and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles of each leg was also recorded (Fig. 1, top). EMG signals were band-pass filtered (10–500 Hz) and sampled, as the other signals, at 500 Hz.

Procedure

The experimental sequence consisted of BEFORE, MOVING, and AFTER conditions, as in Reynolds and Bronstein (2003) and Bunday and Bronstein (2008). Subjects completed baseline trials which involved walking five times from the stationary platform onto the stationary sled (BEFORE condition). Gait was initiated after an auditory cue (3 “beeps”); they stepped with the right leg onto the stationary platform first, then with the left onto the sled, then right leg onto the sled where they were asked to stop and stay still until recording was completed. Each trial lasted for 16 s. Before continuing onto the MOVING trials, each participant was shown how the sled would move. All subjects performed 15 MOVING trials; they were asked to use the available handrails only if absolutely necessary. When the MOVING trials were complete, a clear and unequivocal verbal warning was given that the sled would no longer move; a visual affirmation was given by wedging the sled in place with wheel-stops and ostensibly turning the motor off. All subjects then completed another five stationary AFTER trials for comparison with the BEFORE trials.

Data analysis

Pre- and post-foot-sled contact epochs were derived from the sled-mounted accelerometer and corroborated with foot pressure data. Trunk position along the antero-posterior axis was provided by the Fastrak (Fig. 1, bottom). For stationary trials (BEFORE and AFTER), forward sway was defined as the maximum forward deviation (“overshoot”) of the trunk, relative to the mean final resting stance position in the last 3 s of the trial (Fig. 1, bottom, a). Due to the unstable nature of the MOVING trials data, trunk sway was measured as the maximum forward displacement of the trunk (peak backward to peak forward) (Fig. 1, bottom, b). While both mediolateral and anterior-posterior instability is expected in peripheral neuropathy patients (e.g., Lafond et al. 2004), the mediolateral direction was not recorded as it was not directly relevant to the LocAE, which occurs in the anterior-posterior plane.

Distance traveled was also measured via the trunk position sensor; the total distance from the subjects starting position (the mean of the first 3 s of a trial) to the final resting stance (the mean of the last 3 s; Fig. 1, bottom, c). The velocity at which subjects approached the sled was calculated using the position sensor on the trunk, defined as the mean linear gait velocity in a 0.5 s time window prior to foot-sled contact (Fig. 1, bottom, d).

EMG signals of the left leg (sled contact leg) were rectified and integrated over a 500-ms time window after foot-sled contact (Fig. 1, bottom, e); AFTER trial values were normalized with respect to a mean baseline integrated EMG measured in BEFORE trials 3–5.

The left MG EMG latency during mean BEFORE and AFTER 1 trial was measured from left heel contact from the nonfiltered grand averages. The latency was calculated automatically taking a mean baseline ±3 SD over a 100-ms baseline period at the beginning of the trial and visually corroborated. For graphical display purposes, EMG was low-pass filtered at 35 Hz. Latencies during the MOVING trials could not be measured reliably (due to the motor interference and movement artifact).

Clinical ratings taken from the neurological examination were used to compare against kinematic variables; where appropriate an average was taken for both legs. For a negative (i.e., normal) Romberg, a score of 0 was given; for a positive Romberg (i.e., abnormally increased unsteadiness on eye closure) a score of 1 was given. Ankle reflexes were scored; absent = 2, reduced = 1, and present = 0 (N.B. knee jerks were not included as they were present in all but 1 patient). Touch hypoesthesia scores were based on which part of the lower leg the loss of sensation started, where 6 was the knee (i.e., worst), 1 was the sole of foot, and 0 was no loss of cutaneous sensation. An average was taken for both sharp (pin-prick) and soft (cotton wool) sensation. Vibration hypoesthesia scores were based on ankle quantitative tuning fork measurements from 0 to 8 [which correlate well with postural sway (Bergin et al. 1995) and sensory nerve action potential studies (Pestronk et al. 2004)]; 8 represents a complete loss of sensation. A final PNP score (in %) was defined as the sum total of all clinical sub-scores defined in the preceding text, where 0% represents a completely normal examination and 100% represents worst performance on all clinical tests.

Statistical approach

For each locomotor variable, a mean baseline was taken for each subject by averaging BEFORE trials 1–5 or 3–5 (initial trials in the EMG data were sometimes excluded due to unreliability). The MOVING and AFTER conditions were divided into first and late trials to analyze any adaptation effects or aftereffects, where late was an average of the final five MOVING trials, and the final three AFTER trials. A mixed design ANOVA analyzed each variable for each experimental condition, comparing MOVING and AFTER against mean BEFORE. Factors group (2 levels: PNP vs. NC) and trial (3 “MOVING” levels: mean BEFORE, first MOVING, late MOVING, and 3 “AFTER” levels: mean BEFORE, first AFTER, late AFTER) were investigated. Post hoc tests of significant group effects were Tukey corrected while trial effects were Bonferroni corrected. Specifically, a significant difference between mean BEFORE and first AFTER provides evidence of an aftereffect (Bunday and Bronstein 2008). Any separate specific comparisons between groups or over conditions were made through independent and repeated t-test, respectively. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

The number of PNP and NC who had an aftereffect in trunk sway, gait velocity, and lower leg EMG was determined by assessing if “first AFTER” was greater than “mean BEFORE” plus 2 SD, for each individual subject. Differences between NC and PNP in the percentage of subjects with an aftereffect for each variable were assessed with χ2 statistics, as were clinical and demographic differences in the PNP subgroups (see results).

RESULTS

Direct observation of the subjects during the BEFORE trials confirmed that they all walked onto the stationary sled without difficulty (recall that patient selection required subjects to be able to walk unaided). During the initial moving trials, NC were unsteady, using the handrails on average for one to two trials. The PNP were more unstable than the controls, requiring use of the hand rails on average up to five consecutive trials; initially PNP were given additional manual support by two experimenters for prevention of a backward fall, if required. A manual support was always given as a last resort and so the patients' own movement was preserved, thus all data remained in the analyses. Over the 15 adaptation trials, all subjects' stability gradually improved. In the first AFTER trial, the majority of the NC subjectively reported an unexpected sensation of unsteadiness (a sensation similar to the “broken escalator phenomenon”) (Reynolds and Bronstein 2003), coinciding with a trunk overshoot on mounting the stationary sled. However, only half of the PNP reported the sensation of unsteadiness and, in corroboration, a trunk overshoot was only observed in approximately half of the patients.

Quantitative group data

BEFORE AND MOVING TRIALS.

The only finding during the BEFORE trials was that PNP walked slightly slower than the normal controls [mean = 0.40 ± 0.04 and 0.53 ± 0.24 m/s, respectively; Fig. 2; F(1,23) = 8.268, P = 0.009], this result continues throughout the conditions and remains in the AFTER trials [F(1,23) = 6.051, P = 0.022; Fig. 2, top right]. During the MOVING trials, PNP increased gait velocity similarly to NC [F(1,23) = 1.372, P = 0.254], although they were considerably more unsteady than NC [i.e., they showed increased trunk sway; Fig. 2; F(1,23) = 12.607, P = 0.002]. However, trunk instability gradually decreased, indicating adaptation to the moving sled task, although at a slower rate than in NC (i.e., trunk sway plateaus around trial 3 for NC and in trial 7 for the PNP).

Fig. 2.

Mean (±SE) data for conditions BEFORE, MOVING, and AFTER for all normal controls (NC; □) and peripheral neuropathy patients (PNP; ▴). Numbers along the horizontal axis represent trial numbers. A change from stationary to moving, moving to stationary is represented by a vertical black line. Top to bottom: gait velocity, trunk sway, normalized left TA, and normalized left MG. Note the aftereffect as increased trunk forward sway, gait velocity, left TA and MG particularly in AFTER trial 1. The gray shaded areas represents mean ± 2SD of the BEFORE data for controls and PNP groups, respectively.

In line with trunk sway, left MG is slightly increased in the PNP (Fig. 2), indicating a slightly greater need for postural muscle activation for the control of stability; however this difference does not reach significance [F(1,23) = 0.725, P = 0.403]. Furthermore, both left TA and MG activation did show a similar pattern of adaptation like that of trunk sway [F(2,42) = 39.493, P < 0.001; F(2,46) = 19.519, P < 0.001, respectively; Fig. 2, bottom]. Although, here adaptation for both groups in left TA and MG appears to plateau around trials 3 and 5, respectively.

AFTER TRIALS.

Gait velocity was increased in the first AFTER trial compared with mean BEFORE [F(2,46) = 51.126, P < 0.001], indicating that an aftereffect occurred (P < 0.001; Fig. 2, right).

Figure 2 (right) also shows increased forwards trunk sway during first AFTER trial above mean BEFORE data [F(2,46) = 12.980, P < 0.001], thus an aftereffect was present (P = 0.004). This aftereffect decayed after first AFTER, and by late AFTER, it returned to baseline values (P = 0.585). Trunk sway was similar for both groups throughout the AFTER trials [F(1,23) = 0.873, P = 0.360].

The normalized EMG levels were comparable in PNP and the normal controls. An increase in EMG levels was observed during the first AFTER trial (Fig. 2, bottom; normalized left MG and TA, both P < 0.001); that is, an EMG aftereffect was observed.

Individual data

Subjects in both groups were individually assessed on whether they demonstrated aftereffects in trunk sway and gait velocity data (see methods for defining criteria; Table 1). Notably, PNP showed a high percentage of subjects without a trunk sway aftereffect (NC: 23%; PNP: 58%), although this difference did not quite reach significance [χ2 (1, n = 25) = 3.232, P = 0.072]. Nonetheless, this proportion was never observed in young and elderly normal or labyrinthine defective subjects (Bunday and Bronstein 2008; Reynolds and Bronstein 2003). Accordingly, the PNP were divided into two subgroups; those that had a trunk sway aftereffect and those that did not (PNP+ae; PNP-ae, respectively; Table 2). χ2 tests carried out on the variables gender, age, etiology, length of illness, and PNP clinical score revealed no significant differences between the groups (χ2 P values between 0.212 and 0.558). Thus there appears to be no clinical or demographic factors that differentiate the PNP+ae and PNP-ae subgroups. However, grand averaged motion data during the stationary (after) trials distinguishes movement and EMG patterns in these subgroups (Figs. 3 and 5).

Table 1.

Percentage of subjects with a trunk sway, gait velocity and left MG aftereffect (AE)

| Group | Trunk Sway AE, % | Gait Velocity AE, % | Left MG AE, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| PNP (n = 12) | 41.7 | 100 | 75 |

| NC (n = 13) | 76.9 | 76.9 | 69.2 |

| χ2 | P = 0.072 | P = 0.076 | P = 0.748 |

MG, medial gastrocnemius; PNP, peripheral neuropathy patient; NC, normal control.

Table 2.

Peripheral neuropathy patients with a trunk sway aftereffect (PNP+ae) and with a distance traveled aftereffect (PNP-ae)

| Patient | Gender | Age, yr | Aetiology | Length of illness, yr | PNP Score, %* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Trunk sway after effect | ||||||||||

| PNP01 | F | 40 | Diabetes | 10 | 50 | |||||

| PNP02 | M | 65 | Diabetes | 3 | 19.2 | |||||

| PNP05 | M | 59 | Diabetes | 2 | 32.5 | |||||

| PNP06 | F | 77 | Auto-immune/Rheumatoid | 5 | 32.5 | |||||

| PNP08 | F | 55 | Post Guillain Barre | 18 | 47.5 | |||||

| B. Distance traveled after effect | ||||||||||

| PNP03 | M | 62 | Diabetes | 15 | 40 | |||||

| PNP04 | F | 52 | Alcohol | 6 | 45 | |||||

| PNP07 | M | 72 | Alcohol | n/k | n/k | |||||

| PNP09 | F | 58 | Diabetes | 10 | 60 | |||||

| PNP10 | M | 67 | Idiopathic | n/k | 50 | |||||

| PNP11 | F | 71 | Idiopathic | 3 | 15.4 | |||||

| PNP12 | M | 63 | Diabetes | 20 | 38.8 | |||||

| χ2 | P = 0.558 | P = 0.364 | P = 0.212 | P = 0.540 | P = 0.344 | |||||

PNP score: clinical severity scale derived from the neurological examination (see methods).

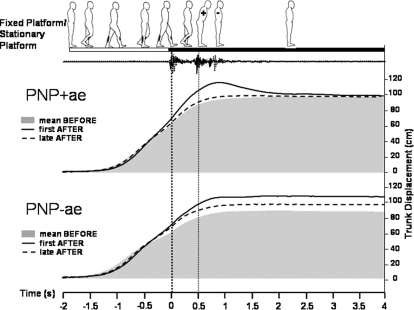

Fig. 3.

Grand averaged trunk movement responses during mean BEFORE,1st AFTER (i.e., the aftereffect) and late AFTER trials in peripheral neuropathy patients with a trunk overshoot aftereffect (PNP+ae) and in those without it (PNP-ae). Data were averaged for baseline mean BEFORE (3–5) represented by shaded area, first AFTER (i.e., the aftereffect; solid line), and late AFTER (3–5) (dotted line) with respect to left heel-sled contact, as indicated by the thick dotted vertical line at time 0. The thin vertical dotted line represents right heel contact, as derived from a sled-mounted accelerometer and foot-pressure data (not shown). Subgroups PNP+ae (top) and PNP-ae (bottom) are represented. Note the large trunk overshoot in the PNP+ae and the increased distance traveled in the PNP-ae. (N.B: baseline mean before distance traveled were not significantly different, t = −1.134, P = 0.283).

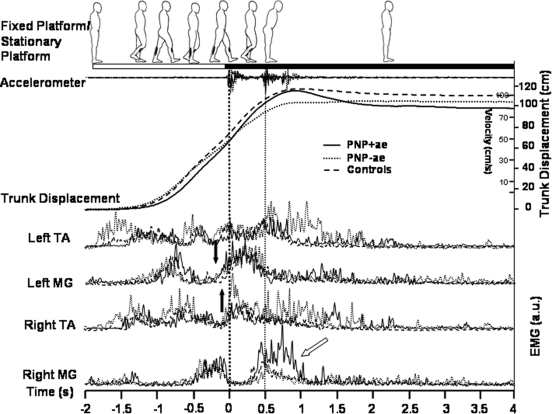

Fig. 5.

Grand averaged PNP+ae, PNP-ae and NC data of movement and EMG responses during first AFTER (i.e., the aftereffect). Data were averaged for first AFTER with respect to foot-sled contact as indicated by the thick dotted vertical line at time 0. PNP+ae (—), PNP-ae (···), and NC (- - -) are represented. Walking, as indicated by EMG activity and the corresponding cartoon man (derived from video footage), is shown from gait initiation to resting stance on the stationary sled. The thin vertical dotted line represents right heel contact as derived from a sled-mounted accelerometer and foot-pressure data (not shown). Black arrows indicate onset differences in left MG EMG bursts between PNP (+ and –ve) and NC. Also note, 1) the increased left and right TA EMG in PNP-ae subgroup, associated with more vigorous stepping movements; 2) anticipatory EMG bursts in left MG (i.e., occurring before left foot-sled contact) in all 3 groups; 3) additional right MG activity in the PNP+ae subgroup (oblique arrow) required for additional braking of the large trunk overshoot aftereffect.

Figure 3 shows the grand averaged trunk sway data for groups PNP+ae and PNP-ae. Baseline data are represented by gray (i.e., mean before), solid lines represent the first AFTER trial, and broken lines correspond to the late AFTER trial. As expected, the PNP+ae subgroup showed a large overshoot of the trunk in the first AFTER trial (i.e., trunk sway aftereffect), whereas the PNP-ae do not (P = 0.003). Comparison of the PNP+ae (who appeared to have a larger than normal trunk forward sway aftereffect; see Fig. 5 for comparison) and the NC, however, did not quite reach statistical significance (P = 0.063).

Because the difference in the magnitude of the trunk overshoot between PNP+ae and –ae subjects is expected by definition, the more important finding is that the PNP+ae and -ae subgroups differ in the total distance walked during first AFTER compared with mean BEFORE. The PNP+ae group showed a minimal increase in the distance traveled in first AFTER with respect to mean before (2.6 ± 5.9 cm; t = −0.012, P = 0.991). In contrast, the PNP-ae group demonstrated a 13.9 ± 4.7-cm increase (t = −2.954, P = 0.025; see Fig. 3 at time 2.5 s onward). This indicates that, although the PNP-ae did not show a trunk overshoot (sway aftereffect), an aftereffect in distance traveled was manifested instead. This increase in distance traveled is not due to subjects taking extra steps as this was reliably checked from foot pressure and sled contact data. Thus the increase in distance traveled was due to increased stride length rather than extra steps. [N.B. In support of the PNP subdivision into two groups, +ae and –ae, when evaluating all PNPs as a whole a significant negative relationship exists between distance traveled and forward sway during first AFTER (r = −0.633, n = 12, P = 0.027)].

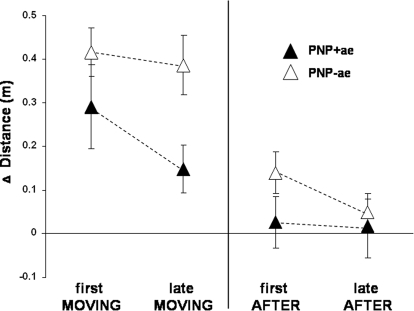

DISTANCE TRAVELED

We investigated whether the segregation of the two PNP subgroups, in terms of trunk sway and distance traveled aftereffect, could be traced to the adaptation (MOVING) trials. Figure 4 shows the relative traveled distance for first MOVING, late MOVING (left), first AFTER and late AFTER (right) in the PNP+ae and PNP-ae subgroups (i.e., Δ distance; mean BEFORE baseline values subtracted). Interestingly, during the MOVING trials, PNP-ae subjects showed significantly increased distance traveled compared with the PNP+ae [F(1,10) = 5.046, P = 0.048; Fig. 4]. Also note that distance traveled in the PNP-ae group remains increased during late MOVING, whereas in the PNP+ae group, distance traveled decreases (Fig. 4). This data segregation was not seen in trunk sway or gait velocity data with both subgroups performing similarly throughout the MOVING trials [trunk sway: F(1,10) = 132.665, P = 0.637, gait velocity: F(1,10) = 1.118, P = 0.315]. Hence distance traveled data for the PNP+ae and –ae subgroups were already segregated during the MOVING trials. In turn, this caused PNP-ae subjects to walk further during the first AFTER trial, causing a distance traveled aftereffect in this subgroup (t = −2.954, P = 0.025) but not in the PNP+ae (t = −0.012, P = 0.991). Importantly, note that these subgroup differences in distance traveled cannot be explained as secondary to gait velocity as there were no differences in gait velocity between the PNP+ and –ae subgroups either in first or late MOVING trials (t = −0.853, P = 0.414; t = −1.102, P = 0.296, respectively) or first AFTER trial (t = 0.337, P = 0.743). Thus increased distance traveled seen in the PNP-ae was incorporated throughout the MOVING trials and was independent of trunk sway and gait velocity.

Fig. 4.

PNP subgroup Δ distance data (mean ±SE) for 1st MOVING, last MOVING, first AFTER, and late AFTER trials. Relative distances (i.e., baseline BEFORE subtracted) walked for subgroups PNP+ae (▴) and PNP-ae (▵). Note the longer distance walked by the PNP-ae subgroup, both in MOVING and AFTER trials, the reduction in distance traveled by the final MOVING trials in the PNP+ae group and the reduction in distance traveled in the final AFTER trials in the PNP-ae group.

We wanted to see if this motor pattern also existed in normal subjects. However, the current subgroups (+ae and –ae) of normal subjects were substantially unequal [i.e., 10 had a trunk sway aftereffect (NC+ae) and only 3 did not (NC-ae)]. So to obtain sufficient numbers of normal subjects with a +ae and –ae, we used normal data from previous experiments using the same protocol (Bunday and Bronstein 2008; Bunday et al. 2006). [N.B. as a result subjects were not fully age-matched (NC-ae range = 20–64 yr; NC+ae range = 55–66 yr), although for this experiment, no age-mediated differences in performance arise (Bunday and Bronstein 2008; additional unpublished observations)]. During the MOVING trials, we found no difference in distance traveled between the subgroups NC+ae (1st: 0.21 ± 0.03 m, last: 0.22 ± 0.02 m) and NC-ae [1st: 0.19 ± 0.04 m, last: 0.16 ± 0.04 m; F(1,18) = 1.127, P = 0.302, n = 10 per group]. Similarly, despite the sub-grouping, no significant differences were seen in trunk sway [F(1,18) = 0.026, P = 0.873] and gait velocity [F(1,18) = 1.561, P = 0.228] during the MOVING trials.

During the AFTER trials, again unlike the PNP, both the NC+ae and NC-ae subgroups revealed a distance traveled aftereffect during first AFTER (t = −3.028, P = 0.014; t = −2.489, P = 0.034, respectively) with no significant difference between the subgroups (t = −0.516, P = 0.612). Thus normal controls do not demonstrate any segregation in distance traveled during the MOVING and AFTER trials, as both subgroups perform similarly. This indicates that the PNP result is uniquely related to the neurological deficit. Indeed when further analysis of distance traveled across first MOVING, late MOVING, and first AFTER was conducted in all four subgroups (PNP+ae, PNP-ae, NC+ae, and NC-ae), a main effect of group was revealed [F(1,28) = 7.078, P = 0.001], where there was no significant difference between subgroups PNP+ae and NC+ae (P > 0.05) or NC-ae (P > 0.05). However, there was a significant difference between PNP-ae and NC-ae (P = 0.001) and NC+ae (P = 0.005).

EMG

Figure 5 shows grand averaged trunk displacement and EMG data during first AFTER (i.e., the aftereffect); note in the normal controls (i.e., the 12 original age-matched subjects), the trunk displacement trace shows a combination of trunk forward overshoot and increased distance traveled (Fig. 5, trunk displacement). Description of the normal EMG pattern during this task can be found in previous publications (Bunday and Bronstein 2008; Reynolds and Bronstein 2003), so we will only focus on salient aspects in the PNP. Throughout, the PNP-ae showed greater bilateral TA activity compared with the PNP+ae; presumably this is related to stronger ankle extension effort required for the longer strides mediating the increased distance traveled in this patient subgroup. However, our epoch of interest is MG after foot-sled contact as we postulated that PNP might have difficulty in counteracting the forward trunk inertia, i.e., braking the aftereffect, due to proprioceptive or stretch reflex loss. In this respect, there was no difference in the magnitude of the MG burst in the left (leading) leg for all three groups. Importantly, MG bursts occurred before, not after, foot-sled contact. Thus the braking of the body forward momentum induced by the aftereffect is brought about by anticipatory MG EMG bursts and not by reflex, post foot-sled contact mechanisms. In fact, MG EMG anticipatory activity occurred earlier in both PNP+ae and PNP-ae (−205 and −192 ms, respectively) compared with the controls (−95 ms; see black arrows, Fig. 5). When measuring the same EMG MG bursts in the mean BEFORE trials in all the groups (not shown), it was found that this anticipatory pattern was already present with only minor differences of 55 ± 17 ms (PNP+ae: −296 ms; PNP-ae: −142 ms; NC: −129 ms) prior to the adaptation phase.

As gait termination is completed, subsequent aftereffect EMG activity in the opposite (right) leg, as it comes to meet the left, reflects the different types of aftereffect expressed; the PNP+ae have increased right MG activity (0.5–1 s) to further brake the large forward overshoot that occurs in this subgroup (oblique arrow, Fig. 5). Simultaneously, contralateral TA bursts in the stance (left) leg further terminates gait by reducing plantar flexion moment at the ankle (normally providing thrust for push off) (Winter 1991). This burst appears to be larger and longer lasting in the PNP-ae subgroup.

DISCUSSION

We investigated gait adaptation and aftereffects in patients with diminished distal peripheral somatosensory input due to PNP. Over half of the PNP did not display a forward trunk overshoot when walking onto the stationary sled during the after trials. Such a high proportion of subjects with an absent trunk overshoot aftereffect was never seen in healthy subjects (Bunday et al. 2006; Reynolds and Bronstein 2003) or in patients devoid of vestibular function (Bunday and Bronstein 2008). Splitting the PNP into two subgroups showed that those patients who did not have a trunk sway aftereffect (PNP-ae) increased the distance walked during the late MOVING trials, which subsequently was expressed as a distance traveled aftereffect rather than a trunk sway aftereffect. This dual pattern was not present in normal subjects, suggesting that, due to somatosensory loss, some PNP used different strategies to negotiate the sled, in turn resulting in distinct aftereffects.

Effects of somatosensory loss on the moving sled adaptation

During the baseline (BEFORE) trials, as expected, the patients walked slightly slower than the normal controls, as often reported in PNP (Dingwell et al. 2000; Katoulis et al. 1997), but showed similar levels of stability (Fig. 2). During the MOVING trials, the patients reached similar levels of increase in approach gait velocity as the controls (Fig. 2, top). This similarity could be partly due to the experimenters' encouragement of the patients and seeing the sled move prior to the MOVING trials. However, more importantly, approach gait velocity is a purely centrally driven, feedforward parameter (N.B. recall gait velocity is measured prior to foot-sled contact) expected to be preserved in the PNP. Similar to other sensory impaired groups (e.g., labyrinthine defective subjects) (Bunday and Bronstein 2008), the PNP are able to generate the internal estimate required to approximately match body and sled velocities.

As expected, the patients displayed abnormally increased trunk sway during the moving trials (Fig. 2) (e.g., Allum et al. 2001; Bloem et al. 2000; Hatzitaki et al. 2004; Horak et al. 1990). Of note, however, unsteadiness levels in PNP gradually declined, indicating adaptation to the moving platform task. The rate of adaptation was slow compared with that of NC (plateau reached in trial 7 vs. trial 3), in agreement with the view that peripheral somatosensory input is important for mediating “on-line” EMG adaptation during locomotion (Mazzaro et al. 2005). Despite patient and experimental differences (e.g., steady-state treadmill walking), Mazzaro et al. (2005) found that, in PNP, adaptation of soleus to stretch was impaired during locomotion. The impaired rate of adaptation during the moving trials observed in our PNP may also be explained by the same mechanism.

Despite the fact that PNP were more unsteady during MOVING trials, a degree of adaptation occurred (i.e., unsteadiness declined). This is similar to what we (but not others) (Black et al. 1983; Buchanan and Horak 2001; Nashner et al. 1982) observed in patients with bilateral vestibular loss with the current paradigm (Bunday and Bronstein 2008). First this could be due to the fact that sensory loss in our PNP was moderate so the remaining peripheral input, appropriately reweighted by the CNS, could play a part in progressively reducing unsteadiness as moving trials progressed. Second, other sensory modalities, such as visual and vestibular inputs, are likely to be involved and weighted accordingly (Buchanan and Horak 1998; Horak and Hlavacka 2001; Horak et al. 1994; Nasher et al. 1982). Third, balance corrections in the PNP could occur through proximal proprioceptive channels, such as the upper leg and hip/trunk muscles (Allum and Honegger 1998; Bloem et al. 2000, 2002), less involved by peripheral neuropathies which usually involve peripheral nerves distally. Finally, the role of anticipation and feedforward control in adaptation during locomotor challenges is considerable as will be discussed in the next section. In our experiment, this component was primarily assessed from analysis of the locomotor aftereffect (LocAE).

Impact of somatosensory loss on the LocAE

It has been shown previously that the release of the LocAE is not specifically dependent on vision but on more general spatial contextual cues (Bunday and Bronstein 2008; Reynolds and Bronstein 2004). Nevertheless, the sensation of physical contact with the sled through the feet could be responsible for releasing the forward trunk sway aftereffect. That is, given that somatosensory information is critical for postural stability on unstable surfaces (Horak et al. 1990; Magnusson et al. 1990; Sinkjaer et al. 2000; Sorenson et al. 2002; Zehr and Stein 1999), stepping onto a surface that has been previously experienced as moving could trigger a “preemptive” postural response. If this was the case, one might have expected either a lack of forward trunk aftereffect in the PNP group as a whole or a more severe sensory loss (worse PNP clinical score) in the PNP without a forward trunk overshoot (PNP-ae subgroup). None of these predictions were observed.

Further analysis showed inter-individual differences; over half of the patients (7/12) did not demonstrate a trunk sway aftereffect (PNP-ae) but, instead, displayed a distance traveled aftereffect (i.e., they walked further). The remaining patients did demonstrate a prominent trunk overshoot aftereffect (PNP+ae), confirmation that the trunk sway aftereffect can be released despite reduced sensation of foot-sled contact.

Different strategies caused the emergence of two subgroups

As mentioned, patients who did not have a trunk sway aftereffect (PNP-ae) showed, instead, an increased distance traveled during the first AFTER trial (Figs. 3 and 4). Therefore it is not that these PNP did not have an aftereffect, it is that it manifested in a different form. As most subjects took just two steps onto the sled (as per instruction and recordings), this increase in distance traveled was due to an increase in stride length, a reportedly feedforward locomotor mechanism (Patla et al. 1989; Varriane et al. 2000; Warren et al. 1986).

The question remains how it was that these two distinct aftereffects emerged within the PNP group. Because the presence of aftereffects after a period of training implies adaptation (Lam et al. 2006), the distinction between the subgroups should also be evident in the adaptation phase. Indeed, the division of the PNP based on the presence of trunk sway aftereffects can be traced to the MOVING trials (Fig. 4); patients who adapted to the moving sled by increasing distance traveled also had little or no trunk sway aftereffect.

It is not clear, though, why the PNP+ae were unable or chose not to use this “traveling further” strategy. However, the distance traveled in PNP-ae showed little change from first MOVING to late MOVING, suggesting that this compensatory strategy was acquired prior to the study. Indeed during postural responses elicited by support-surface motion in standing subjects, trunk EMG changes associated with reduced trunk motion during postural perturbations have been previously noted in PNP (Allum et al. 2001), suggesting that these patients deploy a strategy aimed at avoiding large, potentially destabilizing trunk movements. The unusual gait strategy observed in our PNP-ae may also have been adopted as a general compensatory strategy aimed at reducing large destabilizing trunk movements.

In PNP, trained or learned ankle and hip strategies have been reported to help reduce plantar loading thus aiding the healing of damage caused by the neuropathy (Mueller et al. 1994; Rao et al. 2006). Nevertheless, as in studies discussed previously (e.g., Dingwell et al. 2000; Thies et al. 2005; Thomie and Do 1996), these strategies also resulted in reduced stride length (Mueller et al. 1994; Rao et al. 2006). Thus to our knowledge, an increase in stride length as an anticipatory strategy for PNP facing a challenging locomotor scenario has never been reported before, despite that it makes sense that PNP adopt such a strategy when mounting a moving surface. Therefore the patients' compensatory strategies newly identified in this study are centrally driven adaptive motor behaviors that are triggered by context. As they seem to be preexisting and not dependent on clinical severity, such divergent adaptive behavior could belong with other examples of inter-individual sensory-motor (Rogé 1996; Ronkainen et al. 2008) and neuro-cognitive preferences (Bruder et al. 2005; Fornito et al. 2004). Idiosyncratic responses in the way normal (Asch and Witkin 1992) and vestibular lesions subjects (Bronstein 1995; Isableu et al. 2003; Lacour et al. 1997) utilize sensory cues for spatial orientation and postural control have long been demonstrated. Of note, identification of such individual sensory-motor preferences has allowed clinicians to successfully customize rehabilitation strategies for vestibular patients (Black et al. 2000; Keshner et al. 2007; Pavlou et al. 2004). A similar approach might be valuable in PNP. Thus in future studies of these patients it could be useful to correlate individual strategies in locomotor adaptation with more established tests of sensory-motor preferences (Bronstein 1995; Guerraz et al. 2001; Keshner et al. 2007; Nachum et al. 2004).

Similar braking but distinct aftereffects

The LocAE is due to the release of previously learnt or adapted motor activity when this activity pattern is no longer appropriate (Reynolds and Bronstein 2004). The self-generated postural perturbation observed during the first AFTER trial (i.e., the forward trunk overshoot) is braked by enhanced left anticipatory MG bursts (Bunday and Bronstein 2008) involved in gait termination (Sparrow and Tirosh 2005). Such anticipatory EMG activity occurs earlier in the PNP-ae and PNP+ae than the controls (ca 160 ms), both prior to and postadaptation. Thus when facing an impending internal perturbation, PNP activate gait termination/braking EMG activity earlier. A previous report in deafferented subjects described a related result, namely earlier TA activation during recovery stepping (Thoumie and Do 1996), which suggests that patients' central motor patterns undergo modifications to achieve optimal stability. Similar results are found in healthy subjects when vibrating the Achilles tendon (Slijper and Latash 2004). Our observations of increased anticipation in PNP during gait termination and braking of the LocAE suggests that when somatosensory information about the support surface is diminished, earlier centrally driven EMG activity is elicited to manage a potential perturbation.

When normal subjects, with multiple available inputs, performed our experiments combinations of motor strategies were observed (e.g., combinations of increased distance traveled, gait velocity and trunk sway overshoot). Only by re-analyzing a large number of normal subjects from our files (n = 85) did we manage to identify a similar number of normal subjects without a trunk aftereffect. Thus the PNP appear to have a reduced repertoire as they adopt either the PNP-ae strategy (increased gait velocity in conjunction with increased distance traveled, reducing the likelihood of a trunk sway aftereffect) or the PNP+ae strategy (increased approach gait velocity with normal or less than normal distance traveled and a noticeable trunk overshoot). Thus our study has identified specific strategies utilized by subgroups of patients with somatosensory loss when encountering a moving surface. The different postural strategies are subsequently expressed as distinct LocAEs. However, all PNP were able to anticipate the posturally de-stabilizing nature of the impending aftereffect and accordingly activated enhanced braking EMG activity earlier than controls. In previous studies with this paradigm, we have shown that sensory and cognitive context is important in the expression and characteristics of this LocAE (Reynolds and Bronstein 2004). We now show that “context” during this motor adaptation task includes knowledge of the sensory-motor deficits present in the locomotor system.

GRANTS

Funding from the Medical Research Council is gratefully acknowledged.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank physicians at Charing Cross Hospital, London, in particular Dr. N. Khalil, Consultant Clinical Neurophysiologist, and the Neuropathy Trust for allowing us to contact and study their patients.

REFERENCES

- Allum JHJ, Bloem BR, Carpenter MG, Honegger F. Differential diagnosis of proprioceptive and vestibular deficits using dynamic support-surface posturography. Gait Posture 14: 217–226, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allum JHJ, Honegger F. Interactions between vestibular and proprioceptive inputs triggering and modulating human balance-correcting responses differ across muscles. Exp Brain Res 121: 478–494, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allum JHJ, Honegger F, Pfaltz CR. The role of stretch and vestibulo-spinal reflexes in the generation of human equilibriating reactions. Prog Brain Res 80: 399–409, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asch SE, Witkin HA. Studies in space orientation. II. Perception of the upright with displaced visual fields and with body tilted. J Exp Psychol Gen 121: 407–418, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergin PS, Bronstein AM, Murray NM, Sancovic S, Zeppenfeld DK. Body sway and vibration perception thresholds in normal aging and in patients with polyneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psych 58: 335–340, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black FO, Angel CR, Pesznecker SC, Gianna C. Outcome analysis of individualized vestibular rehabilitation protocols. Am J Otol 21: 543–551, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black FO, Wall C, 3rd, Nashner LM. Effects of visual and support surface orientation references upon postural control in vestibular deficient subjects. Acta Otolaryngol 95: 199–201, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloem BR, Allum JHJ, Carpenter MG, Honegger F. Is lower leg proprioception essential for triggering human automatic postural responses? Exp Brain Res 130: 375–391, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloem BR, Allum JHJ, Carpenter MG, Verschuuren JJ, Honegger F. Triggering of balance corrections and compensatory strategies in a patient with total leg proprioceptive loss. Exp Brain Res 142: 91–107, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronstein AM. Visual vertigo syndrome: clinical and posturography findings. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 59: 472–476, 1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruder GE, Keilp JG, Xu H, Shikhman M, Schori E, Gorman JM, Gilliam TC. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) genotypes and working memory: associations with differing cognitive operations. Biol Psychiatry 58: 901–907, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JJ, Horak FB. Role of vestibular and visual systems in controlling head and trunk position in space. Soc Neurosci Abstr 24: 153, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan JJ, Horak FB. Vestibular loss disrupts control of head and trunk on a sinusoidally moving platform. J Vestib Res 11: 371–338, 2001 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunday KL, Bronstein AM. Vestibular influence on the moving platform locomotor aftereffect. J Physiol 99: 1354–1365, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunday KL, Reynolds RF, Kaski D, Rao M, Salman S, Bronstein AM. The effect of trial number on the emergence of the “broken escalator” locomotor aftereffect. Exp Brain Res 174: 270–278, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh PR, Derr JA, Ulbrecht JS, Maser RE, Orchard TJ. Problems with gait and posture in neuropathic patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Diabet Med 9: 469–474, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cham R, Redfern MS. Changes in gait when anticipating slippery floors. Gait Posture 15: 159–171, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalaska MC. Chronic idiopathic ataxia neuropathy. Ann Neurol 19: 545–554, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz V. Human neuronal control of automatic functional movements: interactions between central programs and afferent input. Physiol Rev 7: 33–69, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dingwell JB, Cusumano JP, Sternard C, Cavanagh PR. Slower speeds in patients with diabetic neuropathy lead to improved local dynamic stability of continuous overground walking. J Biomech 33: 1269–1277, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fornito A, Yücel M, Wood S, Stuart GW, Buchanan JA, Proffitt T, Anderson V, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Individual differences in anterior cingulate/paracingulate morphology are related to executive functions in healthy males. Cereb Cortex 14: 424–431, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JW, Cornblath DR, Alexaner E, Campbell J, Low PA, Bird S, Feldman EL. Ataxic sensory neuropathy and dorsal root ganglionitis associated with Sjogrens's syndrome. Ann Neurol 27: 304–315, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerraz M, Yardley L, Bertholon P, Pollak L, Rudge P, Gresty MA, Bronstein AM. Visual vertigo: symptom assessment, spatial orientation and postural control. Brain 124: 1646–1656, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzitaki V, Pavlou M, Bronstein AM. The integration of multiple proprioceptive information: effect of ankle tendon vibration on postural responses to platform tilt. Exp Brain Res 154: 345–354, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak FB, Diener HC, Nashner LM. Influence of central set on human postural responses. J Neurophysiol 62: 841–853, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak FB, Hlavacka F. Somatosensory loss increases vestibulospinal sensitivity. J Neurophysiol 86: 575–585, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak FB, Nashner LM, Diener HC. Postural strategies associated with somatosensory and vestibular loss. Exp Brain Res 82: 167–177, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak FB, Shupert CL, Dietz V, Horstmann G. Vestibular and somatosensory contributions to responses to head and body displacements in stance. Exp Brain Res 100: 93–106, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inglis JT, Horak FB, Shupert CL, Jones-Rycewicz C. The importance of somatosensory information in triggering and scaling automatic postural responses in humans. Exp Brain Res 101: 159–164, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isableu B, Ohlmann T, Crémieux J, Amblard B. Differential approach to strategies of segmental stabilisation in postural control. Exp Brain Res 150: 208–221, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katoulis EC, Ebdon-Parry M, Lanshammar H, Vileikyte L, Kulkarni J, Boulton AJ. Gait abnormalities in diabetic neuropathy. Diabetic Care 20: 1904–1907, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshner EA, Streepey J, Dhaher Y, Hain T. Pairing virtual reality with dynamic posturography serves to differentiate between patients experiencing visual vertigo. J Neuroeng Rehabil 9: 4–24, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koski K, Luukinen H, Laippala P, Kivela SL. Risk factors for major injurious falls among the home-dwelling elderly by functional abilities. A perspective population-base study. Gerontology 44: 232–238, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacour M, Barthelemy J, Borel L, Magnan J, Xerri C, Chays A, Ouaknine M. Sensory strategies in human postural control before and after unilateral vestibular neurotomy. Exp Brain Res 115: 300–310, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafond D, Corriveau H, Prince F. Postural control mechanisms during quiet standing in patients with diabetic sensory neuropathy. Diabetes Care 27: 173–178, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam T, Anderschitz M, Dietz V. Contribution of feedback and feedforward strategies to locomotor adaptations. J Neurophysiol 95: 766–773, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson ME, Johansson R, Wiklund J. Significance of pressor input from the human feet in lateral postural control. Act Otolaryngol 110: 321–327, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marigold DS, Patla AE. Strategies for dynamic stability during locomotion on a slippery surface: effects of prior experience and knowledge. J Neurophysiol 88: 339–352, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzaro N, Grey MJ, Sinkjaer T, Andersen JB, Pareyson D, Schieppati M. Lack of on-going adaptations in the soleus muscle activity during walking in patients affected by large-fiber neuropathy. J Neurophysiol 93: 3075–3085, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medical Research Council Aids to Examination of the Peripheral Nervous System. Memorandum no. 45 London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1976 [Google Scholar]

- Mueller MJ, Sinacore DR, Hoogstrate S, Daly L. Hip and ankle walking strategies:effect on peak plantar pressures and implications for neuropathic ulceration. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 75: 1196–1200, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachum Z, Shupak A, Letichevsky V, Ben-David J, Tal D, Tamir A, Talmon Y, Gordon CR, Luntz M. Mal de debarquement and posture: reduced reliance on vestibular and visual cues. Laryngoscope 114: 581–586, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nashner LM, Black FO, Wall C., III Adaptation to altered support and visual conditions during stance: Patients with vestibular deficits. J Neurosci 2: 536–544, 1982 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai Y-C, Iqbal K. Simulated movement termination for balance recovery: can movement strategies be sought to maintain stability in the presence of slipping or forced sliding? J Biomech 32: 779–786, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patla AE, Armstrong CJ, Silveira JM. Adaptation of the muscle activation patterns to transitory increase in stride length during treadmill locomotion in humans. Hum Movem Sci 8: 45–66, 1989 [Google Scholar]

- Pavlou M, Lingeswaran A, Davies RA, Gresty MA, Bronstein AM. Simulator based rehabilitation in refractory dizziness. J Neurol 251: 983–995, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pestronk A, Florence J, Levine T, Al-Lozi MT, Lopate G, Miller T, Ramneantu I, Waheed W, Stambuk M. Sensory exam with a quantitative tuning fork: rapid, sensitive and predictive of SNAP amplitude. Neurology 62: 461–464, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao S, Saltzman C, Yack HJ. Ankle ROM and stiffness measured at rest and during gait in individuals with and without diabetic sensory neuropathy. Gait Posture 24: 295–301, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds RF, Bronstein AM. The broken escalator phenomenon: aftereffect of walking onto a moving platform. Exp Brain Res 151: 301–308, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds RF, Bronstein AM. The moving platform aftereffect: Limited generalisation of a locomotor adaptation. J Neuorphysiol 91: 91–100, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogé Spatial reference frames and driver performance. J Ergonomics 39: 1134–1145, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronkainen PH, Pöllänen E, Törmäkangas T, Tiainen K, Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Rantanen T, Sipilä S, Kovanen V. Catechol-o-methyltransferase gene polymorphism is associated with skeletal muscle properties in older women alone and together with physical activity. PLoS ONE 3: e1819, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieppati M, Nardone A. Medium-latency stretch reflexes of foot and leg muscles analysed by cooling the lower limb in standing humans. J Physiol 503: 691–698, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkjaer T, Andersen JB, Landouceur M, Christensen LO, Neilsen HB. Major role for sensory feedback in soleus EMG activity in the stance phase of walking in man. J Physiol 523: 817–827, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slipjer H, Latash ML. The effects of muscle vibration on anticipatory postural adjustments. Brain Res 101: 57–72, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen KL, Hollands MA, Patla E. The effects of human ankle muscle vibration on posture and balance during adaptive locomotion. Exp Brain Res 143: 24–34, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow WA, Tirosh O. Gait termination: a review of experimental methods and the effects of ageing and gait pathologies. Gait Posture 22: 362–371, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thies SB, Richardson JK, Demott T, Ashton-Miller JA. Influence of an irregular surface and low light on the step variability of patients with peripheral neuropathy during level gait. Gait Posture 22: 40–45, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoumie P, Do MC. Changes in motor activity and biomechanics during balance recovery following cutaneous and muscular deafferentation. Exp Brain Res 110: 289–297, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varraine E, Bonnard M, Pailhous J. Intentional on-line adaptation of stride length in human walking. Exp Brain Res 130: 248–257, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren WH, Young Ds, Lee DN. Visual control of step length during running over irregular terrain. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform 12: 259–266, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter DA. The Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Gait: Normal, Elderly and Pathological (2nd ed.) Waterloo, Canada: University of Waterloo Press, 1991 [Google Scholar]

- Zehr EP, Stein RB. What functions do reflexes serve during human locomotion? Prog Neurobiol 58: 185–205, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]