Abstract

Prolonged exposure to consistent visual motion can significantly alter the perceived direction and speed of subsequently viewed objects. These perceptual aftereffects have provided invaluable tools with which to study the mechanisms of motion adaptation and draw inferences about the properties of underlying neural populations. Behavioral studies of the time course of motion aftereffects typically reveal a gradual process of adaptation spanning a period of multiple seconds. In contrast, neurophysiological studies have documented multiple motion adaptation effects operating over similar, or substantially faster (i.e., sub-second) time scales. Here we investigated motion adaptation by measuring time-dependent changes in the ability of moving stimuli to distort the perceived position of briefly presented static objects. The temporal dynamics of these motion-induced spatial distortions reveal the operation of two dissociable mechanisms of motion adaptation with differing properties. The first is rapid (subsecond), acts to limit the distortions induced by continuing motion, but is not sufficient to produce an aftereffect once the motion signal disappears. The second gradually accumulates over a period of seconds, does not modulate the size of distortions produced by continuing motion, and produces repulsive aftereffects after motion offset. These results provide new psychophysical evidence for the operation of multiple mechanisms of motion adaptation operating over distinct time scales.

INTRODUCTION

The analysis of visual motion information is strongly influenced by recent sensory input. Changes in neural processing following exposure to an unchanging motion signal are manifest in the firing rates of individual motion-selective cells in visual cortex, motion visual evoked potentials, and blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) responses to subsequent moving stimuli (for recent reviews, see Heinrich 2007; Kohn 2007; Krekelberg et al. 2006a). This form of short-term experience-dependent plasticity is termed adaptation and is thought to play a vital role in optimizing efficient coding of motion information over time (e.g., Barlow and Foldiak 1989; Clifford et al. 2000; Wainwright 1999). The perceptual consequences of motion adaptation have been extensively studied via the array of striking aftereffects that result from extended exposure to motion in a given direction. The best known of these is the classic motion aftereffect, whereby subsequently viewed stationary scenes are perceived to drift in the opposite direction to the adapting motion (see Mather et al. 1998). Motion adaptation also results in biases in perceived direction (Levinson and Sekuler 1976), speed (Goldstein 1957; Wohlgemuth 1911), and position (Snowden 1998), as well as direction-specific elevations in contrast detection thresholds (Sekuler and Ganz 1963).

A number of previous studies have used perceptual aftereffects to investigate the temporal dynamics of visual motion adaptation (e.g., Bex et al. 1999; Clifford and Langley 1996; Hammett et al. 2000; Hershenson 1989; Hoffmann et al. 1999; Keck and Pentz 1977; Sekuler 1975). Invariably, the magnitude of these effects is found to increase as a function of adaptation duration, yielding adaptation time constants in the order of 3–15 s when fitted with an exponential function. Likewise, systematic lengthening of the interval between adapting and test stimuli reveals recovery from adaptation over a broadly similar time scale. The effect of these manipulations is quantitative—altering the strength but not the nature of the aftereffects induced. Accordingly, formal models of motion-induced aftereffects typically employ a general mechanism (e.g., motion detector gain-control) that is subject to some form of leaky-integrator dynamics (e.g., Clifford and Langley 1996; van de Grind et al. 2003, 2004).

In contrast to the data emerging from psychophysical studies, physiological evidence from the macaque middle temporal cortical area (MT) suggests that multiple distinct motion adaptation mechanisms may be operating over different time scales. Several studies have demonstrated that a prolonged period of adaptation (i.e., several seconds or more) in the preferred direction of a MT neuron reduces its firing rate to subsequent stimuli (Kohn and Movshon 2003; Krekelberg et al. 2006; van Wezel and Britten 2002). These gradual changes are specific to the adapted subregion of the receptive field, suggesting they are inherited from changes implemented earlier in the visual pathway, such as primary visual cortex (Kohn and Movshon 2003). Adaptation and recovery time constants estimated from adaptation effects in cat primary visual cortex (e.g., Giaschi et al. 1993; Vautin and Berkley 1977) are similar to those found with behavioral aftereffect measurements, supporting the presumed causal link between these neural changes and the perceptual aftereffect phenomena. In addition to these gradual changes, a more rapid form of adaptation in MT has also been reported. Following a step change in image speed, many MT neurons display an initial transient peak in firing rate that decays to a sustained level within tens of milliseconds (Lisberger and Movshon 1999; Perge et al. 2004; Priebe and Lisberger 2002; Priebe et al. 2002). In contrast to the effects of more prolonged adaptation, this reduction in responsiveness is maintained when stimuli are moved to different sub-regions of the receptive field, indicating that it either reflects mechanisms intrinsic to MT or else is mediated by feedback from higher levels of the cortical hierarchy (Priebe et al. 2002).

At present it is unknown what perceptual consequences, if any, this form of rapid motion adaptation might have. Traditional aftereffect paradigms, that require observers to make judgments about test stimuli presented after a period of adaptation, are not well suited to assessing processing changes occurring over such brief time scales. Here we take a new approach to this issue. Rather than measuring motion perception directly, we investigate the influence that moving objects exert on the appearance of other stimuli. In particular, we exploit the fact that motion signals can markedly distort the perceived position of nearby objects (see Whitney 2002 for a review). As illustrated in Fig. 1 A, when two spatially aligned static stimuli are briefly flashed adjacent to oppositely moving gratings, they appear to be offset in the direction of motion (Durant and Johnston 2004; Eagleman and Sejnowski 2007; Whitney and Cavanagh 2000). By carefully manipulating the relative timing of moving and static objects, we show that the magnitude of this positional distortion decays rapidly after the onset of motion in a manner comparable to the transient-sustained response profile generated by short-term motion adaptation in MT neurons. The same stimulus configuration can also be used to elicit an aftereffect: if the static objects appear some time after the offset of an extended period of motion, they are typically perceived to be misaligned in the direction opposite to the inducing motion (McGraw et al. 2002; Snowden 1998; Whitney and Cavanagh 2002; see also Nishida and Johnston 1999). We further demonstrate that by varying motion duration, the initial rapid decay of motion influence can be dissociated from such aftereffects, providing behavioral evidence for the operation of distinct mechanisms of motion adaptation operating over different timescales.

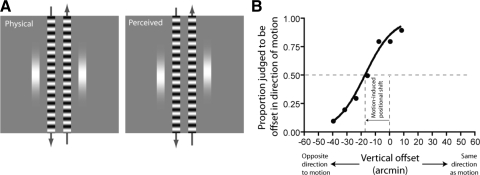

Fig. 1.

A: stimulus configuration employed to measure motion-induced shifts in perceived position. The motion of 2 gratings drifting in opposing directions (indicated by the arrows) induces a perceived vertical offset between briefly flashed target stimuli that are physically aligned. B: typical psychometric function showing quantification of the induced shift. In this, and subsequent figures, positive offset values indicate a shift in the direction of the inducing motion.

METHODS

Observers

Three observers participated in each of the experiments: the two authors and one inexperienced psychophysical observer (M. K.), who was naïve to the specific aims and hypotheses. All observers had normal or corrected-to-normal visual acuity and viewed the display binocularly.

Stimuli and general procedure

Visual stimuli were computed within MATLAB and displayed by a Cambridge Research Systems ViSaGe on a Mitsubishi DiamondPro 2045U monitor (frame rate: 100 Hz, 1,024 × 768 pixel resolution where 1 pixel subtends 2 arcmin, mean luminance: 47 cd m-2, calibrated using a Photo Research PR-650 Spectrascan Colorimeter). The basic task configuration is illustrated in Fig. 1A. Observers were required to judge the vertical alignment of two one-dimensional (1-D) Gaussian target stimuli (width: 1°, σvertical: 1.33° horizontal edge-to-edge separation: 5°, duration: 20 ms), presented adjacent to two inducing gratings that drifted in opposing directions (up/down, width: 1°, horizontal edge-to-edge separation: 1°, full screen height: 25.6°, spatial frequency: 1 cycle/°, temporal frequency: 5 Hz, starting phase randomized on each trial). To avoid the gradual accumulation of motion adaptation within an experimental session, the direction of motion was alternated on each successive trial, and an intertrial interval was imposed that was longer than the preceding period of motion (intertrial interval = motion duration + response latency + 500 ms). A small cross was positioned in the center of the screen, serving as an aid to fixation (width/height: 10 arcmin). To avoid the potential use of the fixation cross (or its afterimage) as a reference for making the alignment judgment, it was subject to square-wave contrast reversal at 10 Hz and was removed during the target presentation interval.

To quantify motion-induced shifts in perceived position, the vertical offset of the target stimuli was manipulated in a method of constant stimuli (7 levels × 30 trials). To produce an offset, the two target stimuli were displaced by equal and opposite amounts (up/down). Because the direction of motion alternated on each trial, these offsets were expressed relative to the inducing motion (i.e., positive offsets indicate a misalignment in the same direction as the inducing motion). This approach further served to null the effect of any alignment bias intrinsic to the observer. Data were accumulated over several experimental sessions to obtain a full psychometric function (see Fig. 1B), which was then fitted by a logistic function of the form

where X is the vertical offset of the target stimuli; PSA is the point of subjective alignment, the physical offset required to null any motion-induced positional shift; and TH is the observer's alignment threshold.

Time course of motion-induced positional shifts

The stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) between the target stimuli and the moving inducers was manipulated for three different motion durations—2,000, 3,600, and 5,000 ms. A SOA of 0 corresponds to when the 20-ms presentation of the target stimuli coincided with the first two 10-ms frames of the motion sequence. Two steps were taken to minimize temporal uncertainty associated with the appearance of the targets. First, SOA conditions were completed in separate blocks, ensuring that no variation in stimulus timing occurred within an experimental session. Second, the fixation cross always appeared a fixed time interval (1,000 ms) prior to the onset of the motion stimuli. This provided a temporal cue for conditions in which the targets appeared prior to motion onset. The order in which observers completed the conditions was pseudorandomized (conditions 1st sampled without replacement until 1 session had been completed of each, process then repeated).

Dissociating stimulus and motion onset

In the time-course experiment described in the preceding text, the inducing stimuli begun to drift as soon as they appeared on the screen. In this instance, the onset of motion is synchronous with the onset of the stimulus itself. To dissociate these two factors, a control condition was run in which the first static frame of the inducing stimuli was presented for 1,000 ms (see Fig. 4A). Target presentation was synched to the onset of motion: the 20-ms target presentation coincided with the last video refresh of the first motion frame plus the second motion frame. The total duration of the motion sequence was fixed at 2,000 ms.

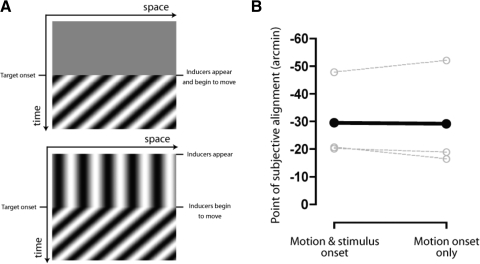

Fig. 4.

Dissociating the effect of motion and stimulus onset. A: space time schematic showing the presentation of target stimuli synched to both the appearance and onset of motion of the inducing patterns (top, motion and stimulus onset condition), or to the onset of motion alone (bottom, motion onset only condition). B: shifts in perceived position for each condition. ○, data for each individual observer; •, the mean.

Preadaptation to motion

A preadaptation technique was used in which observers were presented with two 2,000-ms periods of motion in the same direction separated by a variable interstimulus interval (ISI). Presentation of the target stimuli was either at the onset of the second period of motion or 800 ms later (completed in separate sessions). To avoid the introduction of spurious apparent motion signals, the final frame of the first motion sequence and the initial frame of the second motion sequence had identical phase. The length of the intertrial interval was increased to avoid cumulative adaptation across trials (intertrial interval = 4,000 ms + ISI + response latency +500 ms). Two additional manipulations of the initial (i.e., preadaptation) motion sequence were subsequently employed to investigate the selectivity of the observed effects: the direction of motion was reversed relative to the second motion sequence or the horizontal edge-to-edge separation was increased from 1 to 9°. All other methods were identical to those in the time-course experiment described previously.

RESULTS

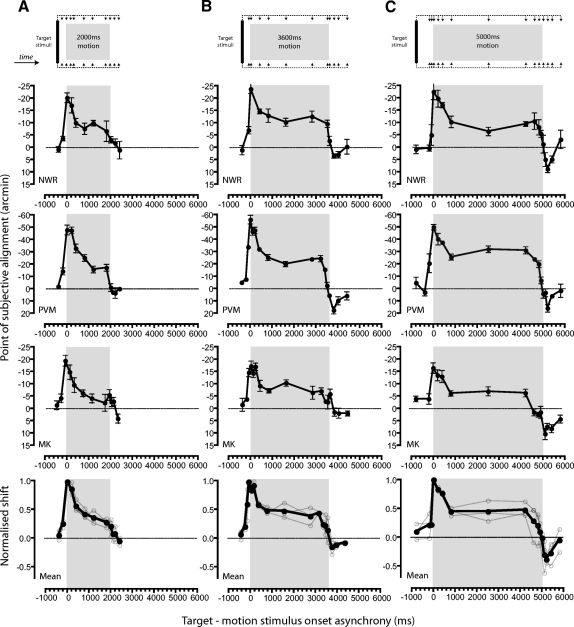

Figure 2 shows the profile of motion-induced positional biases revealed by manipulating the relative timing of the moving inducer patterns and the static target stimuli. In this and subsequent figures, shifts of perceived target position in the direction of motion are indicated by negative PSA values (a physical offset in the opposite direction being required to achieve perceptual alignment). Negative SOA values denote conditions in which the target stimuli appeared prior to the onset of motion. Despite differences in the absolute magnitude of induced positional misperceptions across observers, all showed very similar profiles as a function of SOA.

Fig. 2.

The time course of motion-induced shifts in perceived position. Points of subjective alignment are plotted as a function of stimulus onset asynchrony (SOA) for motion durations of 2,000 ms (A), 3,600 ms (B), and 5,000 ms (C). Negative SOA values indicate conditions in which target stimuli appeared prior to the onset of motion. To aid comparison across conditions, the range of SOAs in which the inducing and test stimuli overlapped in time is indicated by the gray rectangle. Data for individual observers are shown in the top 3 rows in which error bars indicate ±1 SE. Bottom: mean (filled symbols) and individual (unfilled symbols) shifts once normalized relative to the observer's peak effect.

Previous studies suggest that the perceived position of briefly presented static stimuli is distorted by motion signals occurring after their appearance (Durant and Johnston 2004; Eagleman and Sejnowski 2007; Whitney and Cavanagh 2000). For example, Eagleman and Sejnowski suggest that the magnitude of motion-induced positional shifts reflects the accumulation of motion signals within a temporal window spanning ∼80 ms after stimulus presentation. Consistent with this suggestion, we find that positional shifts begin to occur when target stimuli are presented immediately prior to the moving inducers and reach maximum when target presentation is coincident with motion onset (SOA = 0 ms). Simple temporal integration of a uniform motion signal predicts that the magnitude of induced biases should be maintained for any further delays of targets presentation up until ∼80 ms before motion offset. However, this prediction is clearly not borne out in the results. Instead in all conditions, induced positional biases undergo a rapid decelerating decay after motion onset, reaching an asymptotic level slightly less than half of the peak effect beyond SOAs of ∼800 ms. The resulting initial time course is remarkably similar in form to the transient-sustained response profiles produced by short-term motion adaptation in MT neurons (e.g., Lisberger and Movshon 1999; Priebe et al. 2002). To quantify this temporal profile, we first normalized PSAs relative to the peak shift in each condition and averaged across observers (see Fig. 2, bottom). We then simultaneously fitted the segments of the composite time-course functions ranging from motion onset to 800 ms prior to motion offset with an exponential decay function

where a is the normalized effect at asymptote and τ is the time constant of the exponential. The best fitting function was obtained with a = 0.41 and τ = 446 ms and successfully explained 91% of the variance.

Another distinctive feature of the time-course data is that the initial rapid attenuation of induced positional shifts can be dissociated from the gradual development of a repulsive positional aftereffect. Consistent with the results of earlier studies (McGraw et al. 2002; Snowden 1998; Whitney and Cavanagh 2003), we find that the perceived positions of target stimuli presented after motion offset were shifted in the opposite direction to the moving inducers (indicated by positive PSA values). Whereas rapid attenuation of positional misperceptions after motion onset is evident in all conditions, the size of the repulsive aftereffect is clearly dependent on the duration of motion—little or no aftereffect followed 2,000 ms of motion, but progressively larger effects follow periods of motion lasting 3,600 and 5,000 ms.

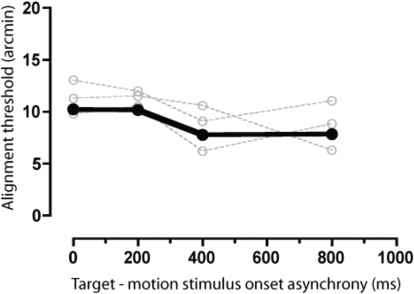

In principle, two types of explanation of the rapid attenuation of induced positional distortions after motion onset are possible: reduction/suppression of the motion signal over time (i.e., adaptation) or changes in the susceptibility of positional judgments to induced biases. The appeal of the former is strengthened by the fact that there is a known neural correlate—indeed, the transient-sustained temporal profile of the motion-induced shift shows a striking resemblance to the time course of short-term motion adaptation in MT. However, it is possible that the motion signal itself could remain uniform over time but that positional judgments are particularly vulnerable to distortion at motion onset. One potential reason for this might be that the moving inducers act to mask the target stimuli when their respective onsets are close in time, making them more difficult to localize. Several lines of evidence suggest that the susceptibility of positional judgments to distortion by motion is heightened under conditions where positional sensitivity is low. For example, motion-induced positional shifts tend to be larger when stimuli are spatially blurred (e.g., De Valois and De Valois 1991; Fu et al. 2001; Whitaker et al. 1998), when they are presented at peripheral locations of the visual field (e.g., De Valois and De Valois 1991; Kanai et al. 2004; Whitney and Cavanagh 2003), or when they are subjected to spatial crowding (Kanai et al. 2004). If excessive masking was responsible for the marked peak in the magnitude of positional biases at motion onset, we would expect to see a concomitant deterioration in positional sensitivity at this time. Contrary to this prediction, however, no systematic differences were found between observers' alignment thresholds for target stimuli presented at, or shortly after the appearance of the moving inducer stimuli (see Fig. 3). An additional possibility is that the susceptibility of positional judgments to distortion at motion onset has a high-level cognitive basis. It has been argued that positional distortions reflect the tendency for observers to treat moving and static stimuli as being parts of a single object (see Eagleman and Sejnowski 2007). Synchronous presentation of inducing and target stimuli might increase the probability of “binding” the stimuli in this way, resulting in larger misperceptions of perceived position. To investigate this possibility, we ran an additional condition in which we dissociated the onset of motion from the appearance of inducing stimuli (see Fig. 4A). Although this manipulation reduces the likelihood of attributing the stimuli to a common source, a consistent shift in perceived position was obtained for target stimuli presented at the onset of motion, regardless of whether this coincided with the appearance of the inducing stimuli (see Fig. 4B).

Fig. 3.

Positional sensitivity at, and shortly after the onset of motion. Mean (•) and individual (○) alignment thresholds are shown as a function of SOA. Data have been collapsed across motion durations.

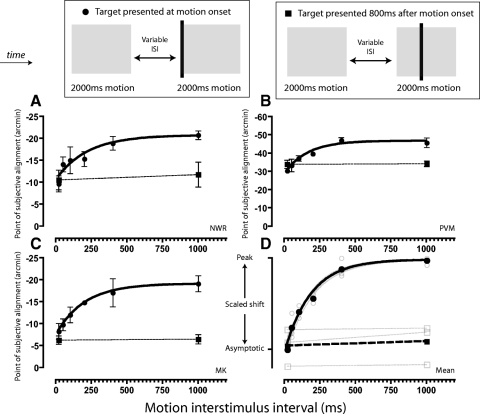

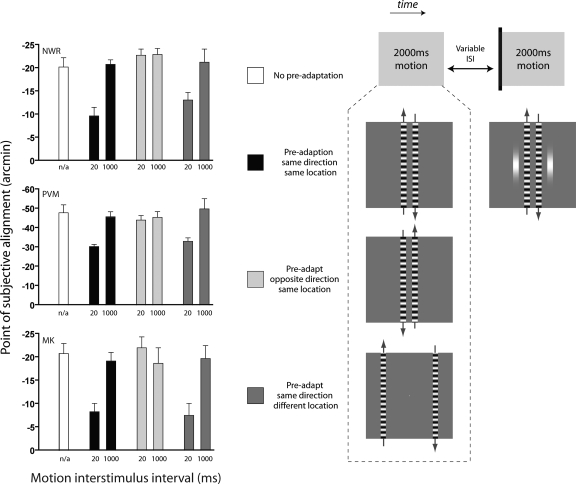

It stands to reason that if rapid adaptation of the motion signal underlies the attenuation of positional distortions after motion onset, it ought to be possible to preadapt observers and selectively eliminate the early transient peak effect for subsequent motion onsets. To examine this possibility, we presented observers with two 2,000-ms periods of motion separated by a variable ISI. The presentation of the target stimuli was synched to the onset of the second period of motion (see methods for details). Results are shown in Fig. 5 (•). When the ISI was brief (e.g., 20 ms), observers showed moderate shifts of perceived position in the direction of motion. In all cases, these shifts were consistent with asymptotic levels previously reported for target stimuli presented >800 ms after motion onset (compare with Fig. 2). Lengthening the ISI produced a systematic increase in the magnitude of the effect, consistent with progressive recovery from short-term motion adaptation. Exponential functions fitted to the data yielded recovery time constants in the order of 200 ms (NWR = 221 ms, PVM = 162 ms, MK = 200 ms, pooled data = 186 ms). For comparison, positional shifts obtained with target stimuli presented 800 ms after the onset of the second period of motion are represented in Fig. 5 (■). Manipulation of the ISI between the two motion intervals had no effect in this instance, indicating that preadaptation specifically reduces the initial transient peak effect observed at motion onset. To further investigate the selectivity of the rapid adaptation mechanism, we next repeated the experiment while manipulating either the spatial location or direction of the motion sequence in the preadaptation phase. As shown in Fig. 6, comparable attenuation of the peak effect at motion onset occurred regardless of whether the preadaptation motion sequence was positioned at the same or a more peripheral retinal location. In contrast, no change in the magnitude of the peak positional shift was found when the two motion sequences moved in opposing directions.

Fig. 5.

The recovery of motion-induced position shifts from short-term adaptation. A–C: points of subjective alignment for each individual observer, plotted as a function of the temporal interval between successive 2,000-ms periods of motion. •, conditions in which target presentation was synched to onset of the 2nd period of motion (i.e., SOA = 0 ms). ■, when target presentation was 800 ms later (SOA = +800 ms). D: mean (•, ■) and individual (○, □) positional shifts, rescaled to range between mean peak and asymptotic levels described in Fig. 2.

Fig. 6.

Specificity of short-term adaptation effects on motion-induced positional distortions. Individual points of subjective alignment are shown for target stimuli presented at the onset of a 2,000-ms period of motion following either: no preadaptation (white bar, data replotted from Fig. 2); preadaptation to motion in the same direction and at the same location (black bars, data replotted from Fig. 5); preadaptation to motion in the opposite direction (light gray bars); or preadaptation to motion at a different location (dark gray bars).

DISCUSSION

Correspondence with short-term motion adaptation in MT

To what extent can the rapid attenuation of positional distortions after motion onset be considered a behavioral analogue of short-term motion adaptation in MT? The decay and asymptote of the positional shifts we have measured is certainly qualitatively similar to the transient-sustained neuronal response profiles reported previously (e.g., Lisberger and Movshon 1999; Priebe et al. 2002), as is the pattern of recovery from adaptation. Furthermore, the direction specificity and broad spatial tuning observed is entirely consistent with the selectivity of short-term motion adaptation reported in MT (Priebe and Lisberger 2002; Priebe et al. 2002). Interpreting more quantitative comparisons between these neural and behavioral phenomena is difficult not least because the precise role played by area MT in the generation of motion-induced positional shifts has yet to be established. Similarities do exist in terms of the relative magnitude of transient and sustained components (see Priebe et al. 2002, Fig. 2). In the sample of MT neurons reported by Priebe and colleagues (2002), the mean ratio of transient to sustained response levels was 2.43, corresponding to a 59% reduction. Remarkably, the best fitting exponential decay function to the motion-position results also yielded an asymptotic level that was 59% of the peak effect (a peak-normalized effect size of 0.41), although the precision of this correspondence is likely to be coincidental. Less similar are the time constant estimates derived from psychophysical and physiological measures. Adaptation (∼450 ms) and recovery (∼200 ms) in the current study was an order of magnitude slower than that found physiologically—Priebe et al. report adaptation time constants ranging from 8 to 85 ms (mean: 25.9 ms) and a mean recovery time constant of 86 ms. A number of factors could potentially contribute to this discrepancy. First, it is clear that motion-induced positional shifts do not provide an instantaneous measure of motion-related neural activity. Rather the magnitude of these effects reflects the accumulation of motion signals over a period of ≥80 ms after the positional judgment is triggered (e.g., Eagleman and Sejnowski 2007; Whitney and Cavanagh 2000). The impact of this temporal summation is to smear the impact of changes to the motion signal in time. Clear evidence of this can be seen in the time-course data around the time of onset and offset of the inducing motion. Although these changes in the motion signal are abrupt, they produce gradual changes in the behavioral effect (see Fig. 2). As described previously, motion-induced positional shifts begin to occur even when the presentation of target stimuli precedes the onset of motion. Likewise, the gradual decline in the magnitude of induced shifts starts at a time point discernibly earlier than motion offset. It is likely therefore that the decay in the magnitude of the effect after motion onset is temporally extended compared with the underlying neural processes that drive it. An additional consideration is the fact that the inducing motion signal is unlikely to be coded by the response of a single motion-sensitive neuron but rather by the pattern of responses across a larger population of such neurons. The precise time course of motion-induced positional shifts is more likely related to the temporal characteristics of this combined population activity. Indeed, even simple population coding schemes (e.g., the ratio between responses in 2 channels) can produce aggregate responses with markedly different dynamics than their constituent components (for example, see Hammett et al. 2000).

Relationship with traditional aftereffect measures

A further consideration is how the different effects revealed by the dynamics of motion-induced positional distortions relate to mechanisms of motion adaptation studied with more traditional motion aftereffect paradigms. Previous psychophysical studies have found that the properties of motion aftereffects differ depending on whether the test stimulus used is static or dynamic. Motion aftereffects in static patterns can be induced by adaptation to motion sequences defined by luminance (1st-order motion) but not by contrast (2nd-order motion) (Nishida and Sato 1995). They also tend to be tightly coupled to the retinal location, spatial frequency, and chromatic composition of the adapting stimulus (e.g., Cameron et al. 1992; Masland 1969; McKeefy et al. 2006) and only transfer partially between the two eyes (Molden 1980). In contrast, motion aftereffects measured with dynamic test stimuli result from adaptation to both first- and second-order motion (Ledgeway 1994), are relatively insensitive to changes in basic visual properties (e.g., Ashida and Osaka 1994; Snowden and Milne 1997), and exhibit complete inter-ocular transfer (Nishida et al. 1994). These differing properties are thought to reflect the fact that static and dynamic motion aftereffects tap into adaptation occurring at different stages of motion processing (e.g., Mather et al. 2008). Recently, Kanai and Verstraten (2005) have reported that dynamic motion aftereffects can be produced from relatively brief (subsecond) exposure to motion, an effect that they interpret as a perceptual manifestation of fast neuronal adaptation. While it is tempting to suggest that these aftereffects might share a common neural substrate to the rapid adaptation effects we observe, some caution is necessary. Whereas our rapid adaptation effects can be dissociated from repulsive positional aftereffects, available evidence suggests that the tuning characteristics of dynamic motion aftereffects and repulsive positional aftereffects are indistinguishable (McGraw and Roach 2008; McGraw et al. 2002; McKeefry et al. 2006). In addition, the recovery time constant of 2 s reported by Kanai and Verstraten is ∼10 times larger than that found in the present study.

Generality of rapid adaptation effects

Short-term adaptation is by no means a unique property of neural responses in MT: rapid decay of firing rates after the appearance of an optimal stimulus is characteristic of neurons in a variety of visual cortical areas (e.g., Hegdé and Van Essen 2004; Kulikowski et al. 1979; Mayo and Sommer 2008; Motter 2006; Müller et al. 1999). An interesting question therefore is whether different forms of perceptual biases induced between stimuli present in the visual field could be exploited to reveal behavioral indices of rapid adaptation in other domains. One advantage of the paradigm employed here is that motion only affects perceived spatial position when presented within a relatively restricted temporal window (i.e., ∼80 ms after the target stimuli) (Eagleman and Sejnowski 2007). Other effects, characterized by temporal integration over much wider intervals, may be less well suited for this purpose. For example, biases in the perceived orientations of spatially adjacent stimuli (the “tilt illusion”) occur when stimuli are separated in time by as much as 200–400 ms (Corbett et al. 2009; Durant and Clifford 2006). Identification of induced perceptual biases requiring near synchronous stimulus presentation will afford the best temporal resolution for future investigations of this kind.

GRANTS

This work was supported by The Wellcome Trust.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank an anonymous reviewer for their suggestions.

REFERENCES

- Ashida H, Osaka N. Difference of spatial frequency selectivity between static and flicker motion aftereffects. Perception 23: 1313–1320, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow HB, Foldiak P. Adaptation and decorrelation in the cortex. In: The Computing Neuron, edited by Durbin R, Miall C, Mitchison GJ. Wokingham, UK: Addison-Wesley, 1989, p. 54–72 [Google Scholar]

- Bex PJ, Bedingham S, Hammett ST. Apparent speed and speed sensitivity during adaptation to motion. J Opt Soc Am A 16: 2817–2824, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- Cameron EL, Baker CL, Boulton JC. Spatial frequency selective mechanisms underlying the motion aftereffect. Vision Res 32: 561–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford CWG, Langley K. Psychophysics of motion adaptation parallels insect electrophysiology. Curr Biol 6: 1340–1342, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford CWG, Wenderoth P, Spehar B. A functional angle on some after-effects in cortical vision. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 267: 1705–1710, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbett JE, Handy TC, Enns JT. When do we know which way is up? The time course of orientation perception. Vision Res 49: 28–37, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Valois RL, De Valois KK. Vernier acuity with stationary moving gabors. Vision Res 31: 1619–1626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant S, Clifford CWG. Dynamics of the influence of segmentation cues on orientation perception. Vision Res 46: 2934–2940, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durant S, Johnston A. Temporal dependence of local motion induced shifts in perceived position. Vision Res 44: 357–366, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagleman DM, Sejnowski TJ. Motion signals bias localization judgments: a unified explanation for the flash-lag, flash-drag, flash-jump, and Frohlich illusions. J Vision 7: 1–12, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Shen Y, Dan Y. Motion-induced perceptual extrapolation of blurred visual targets. J Neurosci 21: 1–5, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaschi D, Douglas R, Marlin S, Cynader M. The time course of direction-selective adaptation in simple and complex cells in cat striate cortex. J Neurophysiol 70: 2024–2034, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein AG. Judgements of visual velocity as a function of length of observation time. J Exp Psychol 54: 457–461, 1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammett ST, Thompson PG, Bedingham S. The dynamics of velocity adaptation in human vision. Curr Biol 10: 1123–1126, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegdé J, Van Essen DC. Temporal dynamics of shape analysis in macaque visual area V2. J Neurophysiol 92: 3030–3042, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich SP. A primer on motion visual evoked potentials. Doc Opthalmol 114: 83–105, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershenson M. Duration, time constant, and decay of the linear motion aftereffect as a function of inspection duration. Percept Psychophys 45: 251–257, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann M, Dorn TJ, Bach M. Time course of motion adaptation: motion-onset visual evoked potentials and subjective estimates. Vision Res 39: 437–444, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai R, Verstraten FAJ. Perceptual manifestations of fast neural plasticity: motion priming, rapid motion aftereffect and perceptual sensitization. Vision Res 45: 3109–3116, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanai R, Sheth BR, Shimojo S. Stopping the motion and sleuthing the flash-lag effect: spatial uncertainty is the key to perceptual mislocalization. Vision Res 44: 2605–2619, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck MJ, Pentz B. Recovery from adaptation to moving gratings. Perception 6: 719–725, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A. Visual adaptation: physiology, mechanisms, and functional benefits. J Neurophysiol 97: 3155–3164, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn A, Movshon JA. Neuronal adaptation to visual motion in area MT of the macaque. Neuron 39: 681–691, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krekelberg B, Boynton GM, van Wezel RJA. Adaptation: from single cells to BOLD signals. Trends Neurosci 29: 250–256, 2006a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krekelberg B, van Wezel RJA, Albright TD. Adaptation in macaque MT reduces perceived speed and improves speed discrimination. J Neurophysiol 95: 255–270, 2006b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulikowski JJ, Bishop PO, Kato H. Sustained and transient responses by cat striate cells to stationary flashing light and dark bars. Brain Res 170: 362–367, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledgeway T. Adaptation to second-order motion results in a motion aftereffect for directionally ambiguous test stimuli. Vision Res 34: 2879–2889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levison E, Sekuler R. Adaptation alters perceived direction of motion. Vision Res 16: 770–781, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisberger SG, Movshon JA. Visual motion analysis for pursuit eye movements in area MT of macaque monkeys. J Neurosci 19: 2224–2246, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masland RH. Visual motion perception: experimental modification. Science 165: 819–821, 1969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather G, Pavan A, Campana G, Casco C. The motion aftereffect reloaded. Trends Cogn Sci 12: 481–487, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mather G, Verstraten F, Anstis S.(editors). The Motion Aftereffect: A Modern Perspective.. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayo JP, Sommer MA. Neuronal adaptation caused by sequential visual stimulation in the frontal eye field. J Neurophysiol 100: 1923–1935, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw PV, Roach NW. Centrifugal propagation of motion adaptation effects across visual space. J Vis 8: 1–11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGraw PV, Whitaker D, Skillen J, Chung STL. Motion adaptation distorts perceived visual position. Curr Biol 12: 2042–2047, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeefry DJ, Laviers EG, McGraw PV. The segregation and integration of color in motion processing revealed by motion after-effects. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 273: 91–99, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motter BC. Modulation of transient and sustained response components of V4 neurons by temporal crowding in flashed stimulus sequences. J Neurosci 26: 9683–9694, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulden B. After-effects and the integration of patterns and neural activity within a channel. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 290: 39–55, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller JR, Metha AB, Krauskopf J, Lennie P. Rapid adaptation in visual cortex to the structure of images. Science 285: 1405–1408, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida S, Ashida H, Sato T. Complete interocular transfer of motion aftereffect with flickering test. Vision Res 34: 2707–2716, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida S, Johnston A. Influence of motion signals on the perceived position of spatial pattern. Nature 397: 610–612, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida S, Sato T. Motion aftereffect with flickering test patterns reveals higher stages of motion processing. Vision Res 35: 477–490, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perge JA, Borghuis BG, Bours RJE, Lankheet MJM, van Wezel RJA. Temporal dynamics of direction tuning in motion-sensitive macaque area MT. J Neurophysiol 93: 2104–2116, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe NJ, Churchland MM, Lisberger SG. Constraints on the source of short-term motion adaptation in macaque area MT. I. The role of input and intrinsic mechanisms. J Neurophysiol 88: 354–369, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priebe NJ, Lisberger SG. Constraints on the source of short-term motion adaptation in macaque area MT. II. Tuning of neural circuit mechanisms. J Neurophysiol 88: 370–382, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekuler R. Visual motion perception. In: Handbook of Perception. Seeing, edited by Carterette EC, Friedman MP. New York: Academic, 1975, vol. v, p. 387–433 [Google Scholar]

- Sekuler R, Ganz L. Aftereffect of seen motion with a stabilized retinal image. Science 139: 419–420, 1963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden RJ. Phantom motion aftereffects—evidence of detectors for the analysis of optic flow. Curr Biol 7: 717–722, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden RJ. Shifts in perceived position following adaptation to visual motion. Curr Biol 8: 1343–1345, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden RJ, Milne AB. Phantom motion aftereffects—evidence of detectors for the analysis of optic flow. Curr Biol 7: 717–722, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Grind WA, Lankheet MJM, Tao R. A gain-control model relating nulling results to the duration of dynamic motion aftereffects. Vision Res 43: 117–133, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Grind WA, van der Smagt MJ, Verstraten FAJ. Storage for free: a surprising property of a simple gain-control model of motion aftereffects. Vision Res 44: 2269–2284, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Wezel RJA, Britten KH. Motion adaptation in area MT. J Neurophysiol 88: 3469–3476, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vautin RG, Berkley MA. Responses of single cells in cat visual cortex to prolonged stimulus movement: neural correlates of visual aftereffects. J Neurophysiol 40: 1051–1065, 1977 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainwright MJ. Visual adaptation as optimal information transmission. Vision Res 39: 3960–3974, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker D, Pearson S, McGraw PV. Keeping a step ahead of moving objects. Inv Opth Vis Sci Suppl 39: S1078, 1998 [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D. The influence of visual motion on perceived position. Trends Cogn Neurosci 6: 211–216, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D, Cavanagh P. Motion distorts visual space: shifting the perceived position of remote stationary objects. Nat Neurosci 3: 954–959, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitney D, Cavanagh P. Motion adaptation shifts apparent position without the motion aftereffect. Percept Psychophys 65: 1011–1018, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wohlgemuth A. On the aftereffect of seen movement. Br J Psychol 1: 1–117, 1911 [Google Scholar]